Abstract

Although Saudi Arabian women increasingly attain leadership positions in a national reform movement, few studies have examined their wellbeing during this time of cultural change. Contributing to filling this gap, we engaged ten Saudi women academic leaders in semi-structured interviews, inquiring into their perspectives on wellbeing. Three thematic sources of wellbeing—ecological building blocks, spiritual wellsprings, and eudaimonic motivations—highlight that these Saudi women leaders are drawing from varied sources, from skydiving or culturally unique iterations of ‘me time’ to socio-spiritual activities and relationships. The women identified stresses including balancing ageing parents and young children with their high-pressure positions and co-workers with outdated mindsets. Describing their work as social contributions, acts of worship, and charitable offerings of knowledge, the women’s voices counter stereotypes while illuminating culturally specific sources of wellbeing across life domains.

1. Introduction: Saudi Women Leading in a Time of Cultural Change

Women in Saudi Arabia have increasingly been attaining positions of leadership since the launch of the country’s Vision 2030 in 2016, which is precipitating significant sociocultural changes [1]. As these changes have gathered momentum, there has been a rise in educational and professional opportunities for women [2,3]. Yet, Saudi women may face unique challenges in optimizing wellbeing, with implications on both their development and leadership trajectories. The country is highly gender-segregated [4], which can have effects on physical and mental health [5] women recently attained the right to drive; and a system of male guardianship (mahram) has only recently been dismantled, whereby men made decisions on many aspects of women’s lives [1,6]. As such, female Saudi academic leaders are situated at an intersection between sociocultural and educational tradition and reform, each of which may hold resources for wellbeing and development, along with sources of stress.

Wellbeing is integral to holistic health at the confluence of physical, mental, social–emotional health [7]. Most research on women in positions of academic leadership and their perspectives on wellbeing has been conducted in North America and Europe; much less has focused on women in Saudi Arabia. While Jradi and Abouabbas [5] reported low levels of wellbeing among women in the capital city of Riyadh from a cross-sectional survey before the launch of Vision 2030, little research has examined wellbeing after the launch. There is scant research examining aspects of wellbeing amongst Saudi women academic leaders specifically, including in terms of how they are balancing the changing responsibilities of work, home, and society as contexts of development. These gaps in the literature contribute to an overarching rationale to gain a clearer understanding of sources of strength and stress amongst women leaders to better support their holistic wellbeing and development. We invited Saudi women academic leaders to describe wellbeing in terms of their engagement in varied life contexts. As an initial exploration into this topic in context, we designed an interpretive, ecological study to capture complexity in the ways that female Saudi academic leaders are negotiating sociocultural change, guided by the primary research question: How do Saudi women in academic leadership positions describe cultivating and maintaining wellbeing? We chose to focus on women specifically given the double emphasis on women in the Vision 2030 documents: both as “great assets” in the development of Saudi society and economy, and as central to families, as building blocks of Saudi society (Vision 2030) [8]. In addition, we focused on women in positions of academic leadership considering that the weight of professional responsibility might accentuate the necessity of maintaining wellbeing and balance across varied life contexts. We reasoned that women academic leaders might already be engaging in self-reflexivity regarding their states of wellbeing in relation to their professional positions at this cultural moment of change.

In the next section, we outline the study’s ecological conceptual frame and review recent literature on Saudi women, leadership, and wellbeing. In Section 3, we describe the study’s methodology; in Section 4, we present three themes constructed as findings; Section 5 discusses implications; and Section 6 overviews limitations and recommendations and concludes the paper.

2. Integrated Conceptual Framing and Extant Literature on Saudi Women’s Leadership

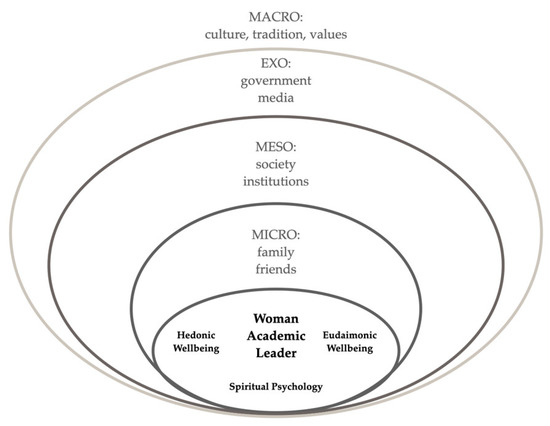

To understand contextual dimensions of wellbeing, development, and leadership amongst urban, Saudi academic leaders, we constructed an integrated conceptual framework of subjective as hedonic wellbeing [9] and psychological as eudaimonic wellbeing [10,11], framed by Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of human development [12,13], including sensitizing concepts from the psychology of religion literature [14,15]. This conceptual framework (see Figure 1) enabled the examination of wellbeing within nested contexts of development and relationships between them and helped make visible “interactions between organism and environment that drive the process of development” [13] (p. 813). Instead of taking a reductionistic view of adults as “static, non-developmental organisms” [16] (p. 69), we took a multifaceted, ecological, lifespan-developmental perspective of the human being as a dynamic, developing person, in interaction with other people and processes and situated within a dynamic, developing society [12]. Understanding individuals as developing within situated contexts shaped the study’s methodology and analytic approach. Centering a woman’s descriptions of her own wellbeing within a unique sociocultural context, considered on various ecological levels from the proximal to the distal, enabled us to focus analytic attention on whole human wellness within contexts shaping ontogenic development.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

2.1. Cultural Context

This study took place within a particular sociocultural context composed of complex and shifting dimensions, which colored all the study’s aspects. Explicating the Saudi Arabian cultural context, and the roles of professional academic women leaders within, aims to deepen both the researchers’ analytic engagement with the data and the readers’ meaning making through understanding the context that our research participants were inhabiting at the time of the study. Since the establishment of the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932, when most of the population was living a traditional, tribal existence [17], the country has been on a rapid path to change with increasing oil wealth, access to education, and collaboration with Western countries. This has been accomplished, in part, through governmental scholarships for Saudi students to study at universities in English-speaking countries, with the expectation that the students would return “with international ideas that will help achieve the national educational goals and make progress towards building a knowledge-based economy” [2] (p.203). In this regard, Saudi female students have come to outnumber male ones [18] and a doctoral degree has come to be considered an effective, if increasingly normative, resource for social and occupational mobility for both men and women. Today, women play central roles in the country’s development into a knowledge-based economy [3].

The sociocultural context of this study is additionally colored by the fact that Saudi Arabia is the birthplace of the Islamic religion and continues to actively incorporate Islam into its institutions [17]. In addition, the country has recently been striving to redirect interpretations towards a moderate emphasis on “hard-work, dedication, and excellence,” specifically identified in Vision 2030 as: “The values of moderation, tolerance, excellence, discipline, equity, and transparency” [8] (p. 16). While some identify barriers to women’s professional and leadership aspirations as rooted in strict interpretations of Islam [19], others see those barriers as more structurally cultural, rooted in a patriarchal society that requires social change (e.g., [4,20,21]). This study aims to probe deeper beneath surface descriptions to examine the ways in which Saudi women describe their own participation in sociocultural change, including the role of religion, and its effects upon their holistic wellbeing and leadership abilities.

2.2. Saudi Women in Leadership

Consonant with empirical studies globally indicating a gap between women and men in senior positions, despite legislations that support gender equality in the workplace [22], studies in Arab countries have also reported fewer women in leadership positions than men. Social perceptions tend to favor men in leadership roles [4] and push women towards fields considered more feminine [23], including education, health, and community services [24]. Saudi women’s participation in the workforce can be considered at the levels of nation, society, and family (Al Faiz, 2013, as cited in [25]). At the national level, recent updates to labor laws include some favorable to women, including involving access to the workforce, maternity leave, and aspects of child support on the job, although there are no explicit legal provisions for renumeration equality and prohibition of discrimination in employment [26]. Increased political and economic support for women is evidenced in the increasing number of Saudi women in leadership roles and in the decision-making process in the country. A recent major shift was women joining the Shura Council (Majlis al-Shura), which is the country’s formative advisory body. Another historic step was the appointment of a woman as Saudi Arabia’s Ambassador to the United States. Some empirical attention has focused on Saudi women’s leadership, including exploring barriers to women’s leadership trajectories [19,20,25,27], and empowerment [17]. Other research has explored how increasing women’s political empowerment may accelerate women’s academic, economic, and managerial empowerment, but not women’s social status, and suggested that academic empowerment may positively impact a wider spectrum [28]. Women have made leadership gains in higher education [6]. While the government is opening opportunities, barriers still exist at the social and family levels, whereby Saudi women often have pressing responsibilities to extended families [25], and a patriarchal society continues to privilege values and customs that limit the social roles of women in society [26]. Structural barriers include a lack of authority and participation in strategizing and decision-making [20]. Despite gains in the new forms of leadership and responsibilities for Saudi women, balance remains a challenge and further research is needed on women’s leadership enablers and strategies to overcome obstacles [27], as well as impacts upon women’s wellbeing.

3. Methodology

The primary research question guiding this study was: How do Saudi women in academic leadership positions describe cultivating and maintaining wellbeing? Within a paucity of extant research on the topic of wellbeing amongst Saudi women in leadership positions, this study was exploratory and interpretivist in nature. To inquire into intimate social worlds, where wellbeing is both individually and socioculturally constructed, we selected semi-structured, individual interviewing as the primary data-collection method. A second method, inviting research participants to draw, diagram, and visually express wellbeing is detailed in Alkouatli and Alanazi (forthcoming). Our varied positions as a Saudi and a Canadian researcher, respectively, as cultural insider and outsider, brought diversity of empirical and lived experiences to the topic, contributed to triangulating the data analysis, and broadening the interpretation.

3.1. Research Site and Participants

This study’s research participants were ten Saudi women in positions of academic leadership in a women’s section of a university who consented to participate. All people and place names are pseudonyms. We selected a university as the site of our study because, as education in general and higher education more specifically are important aspects of Vision 2030, we reasoned that the aims of Vision 2030 might be reflected in the words and lived experiences of the women leaders. In addition, as universities are generally segregated, we anticipated finding more women leaders in a women-only workplace, as compared to a workplace where women would be competing with men for leadership positions. Final inclusion criteria were that a participant must be a Saudi woman of any age, holding an academic position at the rank of Department Head, Vice-Dean, Dean, Vice-President, or higher at the university.

After obtaining ethical approval, we began a process of snowball sampling by inviting women in leadership positions and asking them if they knew others. We invited a total of fifteen leaders to participate in the study, ten of which accepted and five declined, citing heavy workload as a primary reason, which we noted as relevant to our research question. Participants’ faculty positions were arrayed as follows: two Department Heads, one Center Director, three Vice Deans, three Deans, one Vice President; their ages spanned early thirties through late fifties. They were situated in the departments of Business, Computer Science, Education, English Literature, Linguistics, and Translation.

3.2. Data Collection and Thematic Analysis

The data collection process commenced in the first two weeks of June 2021 and consisted of ten individual, 60-minute (average), audio-recorded, semi-structured interviews; six in person on campus and four on Zoom 1. After obtaining consent forms from participants, interviews took place at a convenient time for each research participant; nine in English, one in Arabic. The audio data was immediately anonymized on the recording device itself with an assigned or chosen pseudonym, and professionally transcribed into text. The Arabic interview was professionally translated, transcribed, and checked by the first author. We sent each participant her interview transcript and member-checking took place by email.

Transcription was followed by coding, a fine-grained reading of data, looking for repeated concepts [29] and words identified as key within the conceptual frame. The unit of analysis was the women leaders’ descriptions of wellbeing. The two authors independently read the data, jotting codes and discerning potential code clusters. Each one then started to identify candidate themes and subthemes to present them to the other researcher in a process of analytic triangulation in thematic analysis [30]. After much discussion, we agreed upon three overarching themes: sources, processes, and expressions of wellbeing. Testing for internal consistency included defining each theme and each subtheme and ensuring that each code fit within only one theme. In the interests of space, this paper focuses only on the first theme: sources of wellbeing.

4. Findings: Sources of Wellbeing

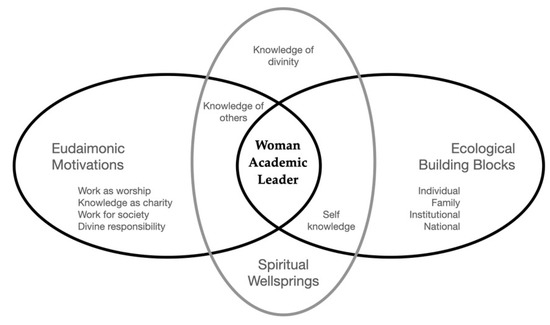

The voices of Saudi female academic leaders resonated across the data corpus with clear descriptions of sources of wellbeing, as novel and culturally relevant contributions to the literature, expressed in three subthemes: ecological building blocks, spiritual wellsprings, and eudaimonic motivations. From the most instrumental to the deepest spiritual, these sources enabled the women leaders to establish wellbeing in the first instance.

4.1. Ecological Building Blocks

This subtheme, defined as the basic requirements to live well, starts with an individual woman, then radiates across the concentric domains of her life. In each domain, the women leaders identified sources of stress and sources of strength as multiple building blocks from which they constructed their senses of wellbeing and approaches to leadership.

4.1.1. Individual Hedonic Wellness: “Me Time”

At its most basic and instrumental, sources of wellbeing started with “me time” clearly defined by Mariam as spending time everyday “doing something that you love”. She elaborated: “Watch a movie or TV show, have some coffee, read a book. I also like to do yoga”. Hana said: “Sit alone, relax, go watch a movie, go with a friend, travel alone—do whatever pleases you”. For Lulua, relaxing with a cup of tea while watching mystery films were ways in which she practiced “mental awakeness”. Annie described analyzing what people did in movies as a practice of Aristotle’s catharsis that she found relaxing. Many participants identified travel as important “me time”; other aspects of seeking pleasure included Hana’s escapades: “I am a bit on the wild side” she said, before describing a recent adventure: skydiving. “After I turned 50, I said, ‘I’m going to do tandem skydiving!’ Yeah, and I did it, ” Sara described her summer recreational recharge in nature: “Just go on a boat in the middle of the lake and jump [laughing]... It really clears the mind!” The women leaders described these activities for pleasure and as foundational for both personal wellbeing and efficacy at work.

Only three participants described exercising regularly. For the other participants, maintaining physical health consisted of watching their health, taking vitamins (Hana), sleeping well (Najiyah), and walking. Lama admitted that while gyms are everywhere, she only did a little bit of walking: “It’s not good for me, and I always get lazy. I will do it later, but I have to do it. I know”. Thus, Lama exemplified the concept of knowing what it takes to be well, but not actualizing it herself.

Beyond these basics, the women leaders identified unique sources and benefits of hedonic “me time”. First, Nour identified that happiness and pleasure are divine rights: “Allah [God] wants us to be happy, to enjoy, to live! We’ve got these misconceptions, even in our childhood, that life is hard. […] that in order to reach this position you have to feel all the pain and to suffer, ” Instead, Nour described: “Allah give us life to enjoy. To make use of the advantages that are available to us and to enjoy our life with ease”. Similarly, Hana identified a saying in Arabic that she translated to mean:

You have the right to please yourself. Giving is really good—and it reflects wonderfully on your wellbeing—but sometimes you need to be a little bit selfish and think about yourself: time for yourself, time to do whatever you want.

In other words, individual wellbeing is a fundamental divine right that, once established, enables a person to extend wellbeing towards others. Many of the women leaders highlighted that an individual’s happiness and wellbeing has benefits on other people: “It’s really important for the overall wellbeing of you and your whole family,” said Mariam, who described going out with friends twice a week. “These things that are important for them, also, not just for me.” Both Mariam and Hana described that a woman’s individual wellbeing had effects on other people in her life, which may be where “me time” dovetails with leadership ability. Lama associated the deliberate cultivation of positive emotions and overall wellbeing as contributing to her leadership abilities: “All my positive thinking and satisfaction in my personal thinking, all contribute to my leadership position and my life as well”. In these ways, the women leaders drew direct links between ‘me time,’ wellbeing, and good leadership.

4.1.2. Family: Immediate and Extended

Around each participant, there were concentric circles of family, echoing Al Mutair et al.’s description of Saudi Arabia’s citizenry as having not only “common religious ties but also tribal ties as well as large traditional family bonds” [31] (p. 1070). For Yamna, “Family comes first,” and for Lulua, “My family—husband, mother, mother-in-law, children—are the most important people in my private life”. As such, family included both immediate (small) and extended (large) family, each of which were sources of both strength and stress.

This subtheme also includes work–family balance because for some, the family provided support, including in terms of childcare; for others, the family required support, which, in some cases, detracted from a woman’s sense of wellbeing and cut into bonding in her nuclear family. Nijayah said: “When I had my first baby, I was doing my Master’s. I was always busy. I would send her to my mom’s house”. She described dropping off her child in the morning and picking her up again at 9 pm. Lama and Mariam too recollected dropping children in the maternal family’s house. Sara, on the other hand, described her extended family saying, “They’re done with us [laughing]!” adding that “other family members at home”—namely, her two teenage sons—took turns caring for her smallest child. Lama pointed out that while, in the past, grandmothers were often happy to take care of grandchildren, life is different in Vision 2030 and grandmothers are different: “Young grandmothers, they now have access to many things; money, entertainment, life. They don’t need to sit and take care of their grandchildren!” She related many grandmothers saying: “I gave enough for my children. I don’t want to raise my grandchildren too!” Hana was herself a living example of a young, active, professional grandmother; she described teaching her son to take care of his own young daughter, saying “You are part of the family, it’s not everything on her [the mother]. No, you should chip in”. She noted that, “He actually used to wake up, change the little girl’s diaper, put her back to sleep”. Here, Hana provided an example of social changes at the level of the family, opening up opportunities for entertainment for women, and grandmothers who are too busy to take care of grandchildren, which creates a space for men to fill.

Lama, a widow, and her children lived with her parents because her mother had Alzheimer’s and needed close care. She identified that she had responsibilities for the wider family, which was a source of stress: “We are not an independent family; we can’t do whatever we want. My father still controls us […] And I don’t want to upset him at this age”. Here, Lama identified that her father dominated the people in the extended family and, while her own three children wanted their privacy, Lama told them: “These are my parents. I don’t want to leave them at this age! We need to help them”. For Lama, providing support for her parents was more important, at this time in their lives, than meeting the desires of her immediate family. She exemplified a culturally unique iteration of the family as a source of both strength and stress.

4.1.3. Social Ecology: “Dealing with Humans”

Many of the participants emphasized the importance of, first, social life on wellbeing and, second, social wellbeing on leadership. Annie deliberately engaged in social relationships that awakened different aspects of herself, spending time with work friends, high school friends, and college friends—“With each one of them, I’m becoming a different self”—in a process of self-development. Sara described drawing support from a particularly close colleague: “We remind each other that not everything is in our hands. […] You do the work, but then you trust Allah, and you watch things fall into place”. Here, Sara and her friend reminded each other of the spiritual reality that things would eventually work out for the best, which highlights a social–spiritual pathway towards wellbeing, as identified in the literature [15,32].

However, a social life requires management and limiting time for socializing was another source of wellbeing, as Yamna described: “Sometimes you have to cancel, but you have to let the other people understand why you did that, and don’t make it as a custom”. Sara elaborated: “Time is precious when you are in a leadership position, and you have family. So, you think about time, and rearrange things”. Yamna made an important distinction between her closest circle of friends, and a wider social circle of inclusion:

I pick very carefully and very passionately who is going to be in my closest circle. But at the same time, I have an open circle for anyone. All of the drivers of the neighborhood, they like to come to our house, because we give them coffee.

Here, Yamna described taking utmost care with her closest social circle yet also maintaining a wider circle of open abundance.

The workplace also brought significant social stresses. Mariam identified “dealing with humans” as the most difficult parts of her leadership position. She elaborated: “Because you can’t work alone, you need people to be with you. No matter how good you are, as a leader, if the people around you don’t believe in what you believe in, and they’re not willing to put in the work, then you’re never going to succeed”. Rihana, as a young department head, identified a problematic mindset rooted in the past amongst colleagues who earned their doctorates a long time ago: “They had that luxury of just sitting, saying their opinion, having the consultant role, and then doing nothing. […] They don’t do the dirty work!” Rihana described this mindset as “valid a long time ago”; in other words, an inactive, consultant-only role is no longer valid in the university workplace. Yet, it persists and is compounded when the university finds someone as Rihana. She described a situation whereby someone was placed above her, “but she wasn’t capable of doing the work,” which led to Rihana taking the burden. When asked how she balances all of this and managed to stay well, Rihana said, “I’m not!” thus exemplifying her workplace as a significant source of stress.

Ultimately, as difficult as human beings are, they are also at the heart of many leaders’ motivations and sources of wellbeing, a finding reflected in other cross-cultural research [33]. Both Annie and Sara identified that human beings are more important than things to do. If managing social relationships outside work constituted a source of wellbeing, managing them within the workplace constituted a source of good leadership, as exemplified in Mariam’s description: “I like to lead in a way where I make the people around me feel like they’re my colleagues and friends—not that I’m the boss or the leader. Involve everyone in the process”.

4.1.4. Institutional Sources of Wellbeing

The university where women leaders worked was the backdrop to much waxing and waning wellbeing and individual development, offering leadership opportunities and challenges. Yamna described: “I cherish those moments when you feel there’s an accomplishment. […] When you see a change in the people”. Najiyah echoed: “When I achieve something […] when a big problem is solved, or something nice happened, I feel fulfilled”. Mariam described drawing strength from her goals: “Every time I become weak, I try to get my strength from that [remembering goals] ”. These sentiments underline identification of accomplishments as aspects of wellbeing [34].

Lulua described the university helping her develop over time: “I belong to this university; I was a student at the Faculty of Education at this college before it became a university, I was 18 years old”. Yamna, who had been with the university for 21 years, expressed a similar sentiment:

My relationship with the university is being grateful. I’m the first girl in my family to have university education. Both of my parents are not educated, they don’t even know how to read and write. And I worked hard when I was in university. My university chose me, I continued my higher studies—MA, PhD—and I got positions. I got training.

In this excerpt imbued with gratitude, Yamna traced her development as being supported by the university, which mirrored the development of the young country. As such, the university represented something even more fundamental to her: “What exactly is it? That place where you get benefits?” Yamna asked, then answered her own question: “No. It’s a place that has meaning in the community, in the society, in the Kingdom. It’s a place that represents a lot of things to females. When I think of the university, I just get goosebumps”. For most of the women leaders, the university was a place to express leadership competence, enjoy belonging, incubate strengths as a source of wellbeing, and develop themselves towards individual and social, educational and professional transformation.

As with the other ecological building blocks, the institution was also a source of stress, which included staff shortages (Rihana); “no established policies, rules, and regulations for the job” (Lama); and a lack of time management (Mariam), exemplified in Najiyah’s description: “Everything had to be done immediately. It was crazy. I was always stressed out”. Rihana experienced a situation whereby someone was placed above her, “but she wasn’t capable to do the work,” which led to Rihana taking the burden. In lacking policies and protocols for optimal work efficiency, the women identified that while the university supported their wellbeing and development, it was also a source of stress.

4.1.5. National Sources of Wellbeing

“Thank God that when I came out of that plane from the States, what I saw before my eyes was 2030” Rihana declared. “Thank God, I did not spend even two years without driving a car!” Satisfaction for Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and its empowerment of women echoed across the data corpus. Sara said that it helps every decision she had to make: “It’s huge”. Rihana described: “I’m not required to cover my face, or to not drive a car, or to not have my independence. It makes a huge difference for me”. She summarized: “It’s contributed positively to my wellbeing!” Yet Vision 2030 also comes with challenges—“because it’s a massive change in all scales, on all levels”—and Rihana offered words of caution: “It’s a very tempting time for women”. In other words, there are so many opportunities unfolding for women, including leadership roles, that taking on too many opportunities could actually have negative consequences on wellbeing.

Across this subtheme of ecological building blocks, employing Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework enabled analysis at various social levels—including individual, family, institution, and government—and the ways in which each contributed to and detracted from women’s senses of wellbeing.

4.2. Spiritual Wellsprings

This second subtheme is characterized by women’s references to the deeper spiritual sources from which they drew intrinsic wellness, as Sara located spirituality as “at the center of my wellbeing” and “a source”. Spiritual wellsprings started with knowing and accepting oneself, epitomized by Mariam, who described wellbeing as: “being happy, being satisfied and content, knowing that you’re just doing your best and you’re happy with where you’re at”. Participants described self-reflection as resulting in productive self-knowledge: “reading, educating yourself, and finding who you are first” (Yamna). Sara described a mechanism of self-knowledge: “I listen to my mind and body that I have to take a break!” Rihana identified: “At the end, I’m a female and I need to be happy about myself”. A large part of Rihana’s wellbeing was doing what she needed to feel happy about herself. Nour described a sense of self-love—“I have to love myself, make it my first priority”—and self-acceptance: “And appreciate all the things in my life and appreciate even sometimes my mistakes”. Accepting one’s own humanity and the inevitability of making mistakes was part of a larger humility encompassed in Hana’s advice to younger women in leadership positions: “Be fair. You don’t know what others are going through. […] It’s difficult enough to understand yourself. How are you going to understand others?”

The women leaders’ self-knowledge was expressed through knowledge of (and empathy towards) others, which seemed to contribute to their leadership practices. For example, Hana identified attentiveness towards her faculty colleagues as a cornerstone of her leadership: “They feel at ease talking with me and I’m a very available to them. No matter how stressful it becomes, I totally believe that the core of success is communication”. Similarly, Yamna described a high degree of social–emotional awareness in wanting to position herself near her team physically: “I felt it was very important for me to be just there within the same space, for me also to observe and understand my team”. This physical proximity translated into valuable data—“You understand those who talk a lot, those who are very timid and shy, those who are very loud. […] You’re collecting tools so that whenever the time comes, you can really talk to that person and use the right context, the right topics, even the right words!”

If striving to know oneself and others were two types of spiritual wellsprings, striving to know divinity was another. Nour illustrated a link between the two, saying: “I evaluate myself on a daily basis. ‘Today, I did this; wow, it’s amazing!’ and I give myself time to feel grateful to myself and to Allah that He guided me do this”. Here, Nour revealed a two-step process of self-evaluation and gratitude—to herself and to the source of her guidance. Wellbeing is not about being perfect and gratitude is fine-grained. Nour said: “It’s not a matter of, ‘I have to wait until the big picture becomes perfect, and then start to feel proud.’ No, even the small things that I’m doing”.

Most of the women leaders identified a deep sense of spirituality as the basis of establishing wellbeing. Sara identified spirituality as “huge in my life” and elaborated how it contributed to her wellbeing: “My belief in Allah strengthens my wellbeing and mental health. It’s a source. […] Because when you fall back, you’re not falling to nothing: there’s something that you’re leaning on. You have protection, you have a solid foundation”. Here, Sara indicated that her faith—knowing that she is unconditionally supported by a larger, powerful force—establishes wellbeing and colors the other domains of her life, including mental health. Annie, too, said, “Our spiritual connection with God […]. We find peace in our prayers and our worship, reading Qur’an and praying”. Najiyah shed light on how those practices engendered senses of peace by describing setting aside worry and focusing on spiritual practices. She described reciting and contemplating on a particular verse of the Qur’an (15:97–99) to help overcome distress and unhappiness, saying: “It’s like something that washes me from inside. It removes all the negative feelings”. Sara described a type of cognitive framing: “What’s greater than work? What’s more important? Allah is bigger than everything. […] So, we work for something beyond this life. That’s why I don’t make big deals of things. I minimize them”. In this description, Sara indicated an expansive vision on her life, where daily irritations are, in reality, small.

Some of the participants described cultivating particular character traits, such as modesty and kindness, as important in leadership. Yamna described the Prophet Muhammad’s character, including humility in leadership, as “a model that you can follow”. She described this as disciplining oneself and being modest: “I do not want to be arrogant. I just want to feel humble”. Lama articulated kindness as part of good leadership, saying: “I am a little bit kind with people. I understand their situation, so they always get back to me being good and kind”. Yamna identified these leadership abilities as aspects of personal character but simultaneously related to religion, saying, “not every religious person can do this […] But it’s related to our religion: Islam very clearly say to be kind with people, to be kind to with others”. Finally, Nour triangulated her relationships with other people through a divine perspective: “Allah created me with all these haquq [rights],” which do not depend on other people. In other words, rights do not originate in other people, nor can other people take them away. Therefore, no matter what other people do or say, “it doesn’t, and it shouldn’t, harm me because and I get my rights from Allah”. Keeping this divine perspective in mind enabled Nour to balance the ups and downs of dealing with other people.

Ultimately, while the Islamic values emphasized in the Vision 2030 documents center those of “moderation, tolerance, excellence, discipline, equity, and transparency,” the women in this study highlighted additional potent values in establishing wellbeing and informing leadership: including deep faith as a solid foundation and source of wellbeing, balance, and mental health; gratitude, guidance, and destiny; de-prioritizing daily irritations in light of a larger sacred reality; and gentle power as exemplified in prophetic leadership. Spiritual wellsprings seemed to directly contribute to women’s wellbeing and, simultaneously, motivated eudaimonic motivations expressed in leadership, evidenced as originating here.

4.3. Eudaimonic Motivations

This final subtheme is defined in harmony with the literature on eudaimonic wellbeing as working, living, and being with a larger meaningful life purpose [11]. The women leaders’ eudaimonic motivations were characterized by working for community goals, cultural change, destiny, and a divine responsibility to self, others, and country. In the context of being a department head, which is “very heavy work,” Rihana advocated for people with disabilities and spread awareness in aiming for cultural change. She described that “making a change” was the most important aspect of her work. Sara also said: “We’re not just working for ourselves, and for the job; it’s a bigger purpose beyond ourselves. And this is what drives me”. She elaborated that the passion can be lost if you are only looking for self-benefit: “But if you really focus on what’s beyond yourself, that’s what matters and it’s really rewarding”.

The women leaders also derived meaning in their leadership positions as divinely orchestrated. Yamna shared her perspective that, although she was from a “simple” family, she saw herself as having been divinely placed at the university to do particular work: “You are on a mission. Allah chose you for something. Build on it. Contribute to it”. Her perspective was colored with gratitude for being chosen to do this work, which she aligned with the overarching mission of the whole institution. Nour articulated a similar sentiment, whereby Allah “prepared me to start the journey of being aware”. Sara, too, identified working to fulfill a divine responsibility: “The greater cause of constructing earth and building humanity, this is the Islamic value of aimar al ard (building the earth). She translated this to mean: “You contribute to society. You really do what you’re supposed to do. You fulfill your purpose”. Similarly, Najiyah said, “I’m not doing this for selfish reasons; I’m doing this for the good of others. So, I look at it as a form of ibada, worship”. Seeing her work as an act of worship was echoed by other participants. Annie articulated her work as zakat al ilm, where zakat means purifying dues or charity, which is itself an act of worship, and ilm means knowledge: “The zakat of your knowledge is that you produce it whenever needed, even if you’re not paid—voluntarily. You offer!” Annie, Najiyah, Rihana, Sara, and Yamna illustrated culturally specific perspectives on their work as a much more than just salaries or academic positions. These leaders saw deeper value in their work as acts of worship, divinely positioned, and were expressed in various eudaimonic motivations.

4.4. Summary of Themes

In summary, these women leaders’ descriptions of their sources of wellbeing—illustrated in the three subthemes of ecological building blocks, spiritual wellsprings, and eudaimonic motivations—indicated that they knew what they needed to construct and maintain wellbeing and their own development. Some identified wellbeing directly, saying, for example, “I’m well. I am very well!” (Yamna). Others embodied an overarching ease, which they described as encompassing periodic difficulties. Others prioritized making time to pursue the activities that made them happy: physically, socially, spiritually. On the other hand, some women described not being able to actualize their knowledge of what they needed to be well, illustrating struggling towards wellbeing, including in comments like: “When I look in the mirror, I don’t like what I see”. (Rihana) and “I was not well. I was unhappy all the time” (Nijayah). In both cases, the women described a work–life imbalance that eroded their senses of wellbeing. Yet, even the participants who described not being optimally well by their own definitions knew theoretically what they needed to move towards wellbeing in a larger sense. “I should have time for doing exercise […] to spend with my friends, with my family. Enough time to do research” (Najiyah). As such, conceptual and practical indications of sources of wellbeing were imbricated throughout the data. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Summary of themes.

5. Discussion and Implications

Our exploratory goal was to examine wellbeing in the voices of Saudi women academic leaders themselves. Given the complex sociocultural worlds the women leaders inhabited, capturing wellbeing required the multiple analytic lenses of hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing within an ecological framework [12], which enabled analysis at various social levels. Limitations of this study include that while semi-structured interviews enabled in-depth discussion on intimate aspects of culturally-situated sources of wellbeing, other concurrent measures of wellbeing would have enabled triangulation of the women leaders’ perspectives. While the women leaders clearly suggested that being well had effects on their development and their leadership abilities, further research is required in probing this relationship. As it was, the women leaders echoed literature on myriad aspects of wellbeing, including physical health, social engagement, intellectual stimulation, and professional accomplishment, with sources specific to this cultural context. Taken together, the data suggested two reciprocal sequences, as iterations of wellbeing situated within the social ecology of this place in time: one involving spirituality and the other involving nationality. These two sequences are explored below, as implications of the study and starting points for further research.

5.1. Spirituality Shaping Eudaimonic Expressions

The women leaders echoed the literature on spirituality’s contribution to sources of wellbeing [14,15], exemplified in statements including: “My belief in Allah strengthens my wellbeing and mental health. It’s a source” (Sara). For these women leaders, spirituality holds intrinsic worth in imbuing a sense of wellbeing across emotion and cognition. Their descriptions suggest that another function of a spiritual perspective may be to organize thinking, particularly towards minimizing stressors and irritations, which evokes Diener and Seligman’s [35] suggestion that happy people’s emotional systems “react appropriately to life events” (p. 81). Embodying Emmons’ [36,37] description of spiritual intelligence, some of the women leaders cognitively employed the scope of transcendence—“Allah is bigger than everything” (Sara)—to minimize daily stressors.

However, spirituality played another important compound function: motivating and informing the activation of eudaimonic activities, from Yamna’s opening her house to the drivers of the neighborhood, following in the way of her Prophet’s generous character, to Annie’s desire to contribute zakat of knowledge to her colleagues at the university. Islamic spirituality inspired eudaimonic activities and simultaneously provided unique methods through which the women executed those activities. It provided the why—work as a form of worship (Najiyah); “Allah chose you for something” (Yamna)—as well as the how: “Build on it” (Yamna), “You offer” (Annie), and “focus on what’s beyond yourself” (Sara). This implication suggests that while spiritual sources and eudaimonic manifestations of wellbeing should be supported, more research is needed on the relationship between the two in understanding its mechanisms and its impacts on human development.

5.2. Women’s and National Development

Critics assert that the recent national efforts towards women’s empowerment are part of a superficial “rebranding effort from the top,” aimed at improving international perceptions of Saudi Arabia [37]. Others suggest that fostering opportunities for women is a way for the state to extend its scope through female buy-in [18]. Others herald the recent changes as significant [26], which was the dominant sentiment amongst the women leaders as participants of this study. Regardless of intentions, the national efforts supporting women at individual and social levels emanated through a university offering opportunities for development, which the women leaders described as seizing in real time and as contributing to their wellbeing and ongoing development. Echoing Alghamdi et al. [1] that the national plan is a “tool for development” (p. 194), the women leaders described Vision 2030 as enhancing their wellbeing: Sara described feeling respected; Rihana enabled; Annie and Yamna entrusted with responsibility; Lama and Hana supported by initiatives for professional development and logistical support, such as childcare; and all of them empowered by leadership roles. Additionally, these women leaders’ descriptions of wellbeing touched upon some of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—directly and indirectly, attained and in progress—including good health and wellbeing; quality education; gender equality; decent work and economic growth; reduced inequalities; and peace, justice, and strong institutions (UN, 2015; 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, and 16, respectively) [22].

Yet, as the nation supports women’s development, these women described being inspired in turn to support the nation’s development. Their descriptions evidenced contribution as the most rewarding aspect of their lives and work: Rihana’s “making a change”; Najiyah’s “working for others”; and Sara’s motivating her team towards “a purpose beyond themselves and a purpose for the community”. These eudaimonic activities served to connect individual women leaders, through their families and social circles, and the women they were leading at work, to the national vision to develop the country. While this implication illustrates how cultural context shapes individuals, it simultaneously illustrates how individuals contribute to shaping culture—particularly significant given that these women were in positions of leadership, mentorship, and education at a university, developing next generations.

The women leaders’ descriptions of wellbeing presented a snapshot of an entire country in flux: Yamna’s description of being the first woman in her family to be educated; Rihana’s description of an old mindset, rooted in the past, versus a new fresh one; Hanna’s description of teaching her son to care for his infant daughter; Sara’s teenage sons caring for their smaller brother; Lama’s description of grandmothers too busy with life opportunities to care for young grandchildren. These descriptions evidence cultural change unfolding at the present moment that requires more research.

6. Recommendations and Conclusions

Although Saudi women increasingly attain leadership positions, including in universities, few studies have inquired into their senses of wellbeing and human development. We engaged ten Saudi female academic leaders in semi-structured interviews to answer the primary research question: How do Saudi women in academic leadership positions describe cultivating and maintaining holistic wellbeing? While the integrated conceptual frame made cultural variables visible across ecological domains, the method of semi-structured interviewing enabled us to inquire into those variables more closely. The voices of Saudi female academic leaders offered expansive and culturally situated understandings of sources of wellbeing in three themes—ecological building blocks, spiritual wellsprings, and eudaimonic motivations—which may also be informative in different cultural contexts.

Taken together, these themes suggest that Saudi women academic leader’s roles are currently in transformation, with some significant benefits and some sources of stress. Tentative recommendations might be drawn. First, potentially generative sources of women’s wellbeing intrinsically exist within a culture that centers social connections, spirituality, and gratitude perspectives, especially when framed by institutional support. Highlighting these sources may be helpful to other women in other professions and places. Second, while most women were able to identify the ingredients of wellbeing, some were not able to actualize them. Further investigation is needed in helping women in this context enact aspects of holistic wellbeing and to bridge the gap between theoretical understandings of wellbeing and practical applications for development. As such, this study contributes cultural dimensionality to the existing literature on academic leadership, wellbeing, and development, including towards “an indigenous positive psychology” [38] and as a starting point for more research in Arab–Muslim cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception, design, and data collection. Analyses were independently performed by each author, who then engaged in collaborative analysis. C.A. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; R.A. wrote Section 2.2 and commented on all drafts of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Princess Nourah bin Abdulrahman University (protocol code IRB; H-01-R-059 on 27 May 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not appliable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Some COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were still in place at the time of the study. In addition, one of the participants had already traveled for her summer vacation. Zoom proved an effective interview option. |

References

- Alghamdi, A.K.H.; Alsaadi, R.K.; Alwadey, A.A.; Najdi, E.A. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030’s Compatibility with Women and Children’s Contributions to National Development. Interchange 2022, 53, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.K. The Road to Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Expatriate teachers’ pedagogical practices in the cultural context of Saudi Arabian higher education. McGill J. Educ. 2014, 49, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazawi, A.E. The Academic Profession in a Rentier State: The Professoriate in Saudi Arabia. Minerva 2005, 43, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A. Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements. Int. Educ. J. 2005, 6, 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jradi, H.; Abouabbas, O. Well-Being and Associated Factors among Women in the Gender-Segregated Country. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, A.; Jones, K. An Overview of the Current State of Women’s Leadership in Higher Education in Saudi Arabia and a Proposal for Future Research Directions. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Factsheet. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Saudi Arabia Government (2017). Vision 2030. Available online: www.vision2030.gov.sa (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Well-Being With Soul: Science in Pursuit of Human Potential. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R.A. Spirituality: Recent progress. In A Life Worth Living. Contributions to Positive Psychology; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Csikszentmihalyi, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H.G.; Al Shohaib, S. Health and Well-Being in Islamic Societies: Background, Research, and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, C. Models of adult development in Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory and Erikson’s Biopsychosocial Life Stage Theory: Moving to a more complete three-model view. In Handbook of Research on Adult Learning and Development; Smith, M.C., DeFrates-Densch, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Al-bakr, F.; Bruce, E.R.; Davidson, P.M.; Schlaffer, E.; Kropiunigg, U. Empowered but not equal: Challenging the traditional gender roles as seen by university students in Saudi Arabia. FIRE Forum Int. Res. Educ. 2017, 4, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Renard, A. A Society of Young Women; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, J. Cracking the walls of leadership: Women in Saudi Arabia. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 32, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, H. Challenges facing women leaders in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2011, 14, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, A. Enable Workers: An Introduction to the Improvement and Continuous Development; IPA, The Arab Organization for Administrative Development: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/12/519172-sustainable-development-goals-kick-start-new-year (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Jamjoom, F.B.; Kelly, P. Higher education for women in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In Higher Education in Saudi Arabia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Abalkhail, J.M. Women and leadership: Challenges and opportunities in Saudi higher education. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.C. Saudi Women Leaders: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Arab. Stud. 2015, 5, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, C.; Muftah, H.A. Impact of the legal context on protecting and guaranteeing women’s rights at work in the MENA region. J. Int. Women s Stud. 2020, 21, 98–121. [Google Scholar]

- Alomair, M.O. Female Leadership Capacity and Effectiveness: A Critical Analysis of the Literature on Higher Education in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. High. Educ. 2015, 4, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, M.M.Z.; Alkhateeb, T.T.Y.; Mahmood, H.; Abdalla, M.A.Z.; Qaralleh, T.J.O.T. The Role of the Academic and Political Empowerment of Women in Economic, Social and Managerial Empowerment: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Economies 2020, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mutair, A.; Alhajji, M.; Shamsan, A. Emotional Wellbeing in Saudi Arabia During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Risk Manag. Heal. Policy 2021, 14, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; Stern, R. Gratitude as a Psychotherapeutic Intervention. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fave, A.D.; Brdar, I.; Wissing, M.P.; Araujo, U.; Solano, A.C.; Freire, T.; Hernández-Pozo, M.D.R.; Jose, P.; Martos, T.; Nafstad, H.E.; et al. Lay Definitions of Happiness across Nations: The Primacy of Inner Harmony and Relational Connectedness. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E. Very happy people. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons, R.A. Spirituality and Intelligence: Problems and Prospects. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2000, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.L. Saudi Women Driving Change? Rebranding, Resistance, and the Kingdom of Change. J. Middle East Afr. 2020, 11, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.; Pasha-Zaidi, N. Positive Psychology in the Middle East/North Africa: Research, Policy, and Practise; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).