The Best Welfare Deal: Retirement Migrants as Welfare Maximizers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Retirement Migration and the Welfare State

2.2. The Welfare State for Mobile Retirees

2.3. Social Services Available for Retirement Migrants in Spain

2.4. Hypotheses

“Germany seems not to think of Germans abroad living long-term or permanently abroad as a population of citizens maintaining ties, or needing assistance, but rather as having become citizens or long-term residents elsewhere, perhaps because of its long history as an emigration country. Indeed, there is neither an explicit emphasis on German emigrants nor are there many policies in place which are intended specifically for them. Rights are largely granted on the basis of residence (in Germany), rather than (German) citizenship. Two exceptions do emerge, with access to voting rights and to pension rights strongly facilitated. Other rights are granted only on an exceptional basis, with consular authorities playing a role in facilitating that access”.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Project

3.2. European Retirement Places

“European Retirement Places (LER) are those in which, as a joint effect of the progressive aging of the population; the increase in the standard of living and autonomy of citizens; as well as the possibilities opened up by European integration, a large contingent of elderly citizens (the vast majority retired) from other Member States of the European Union are settling. Those elderly citizens have a vocation of residing in the new places more or less permanently”.[50]

3.3. Data Collection and Methods

4. Results

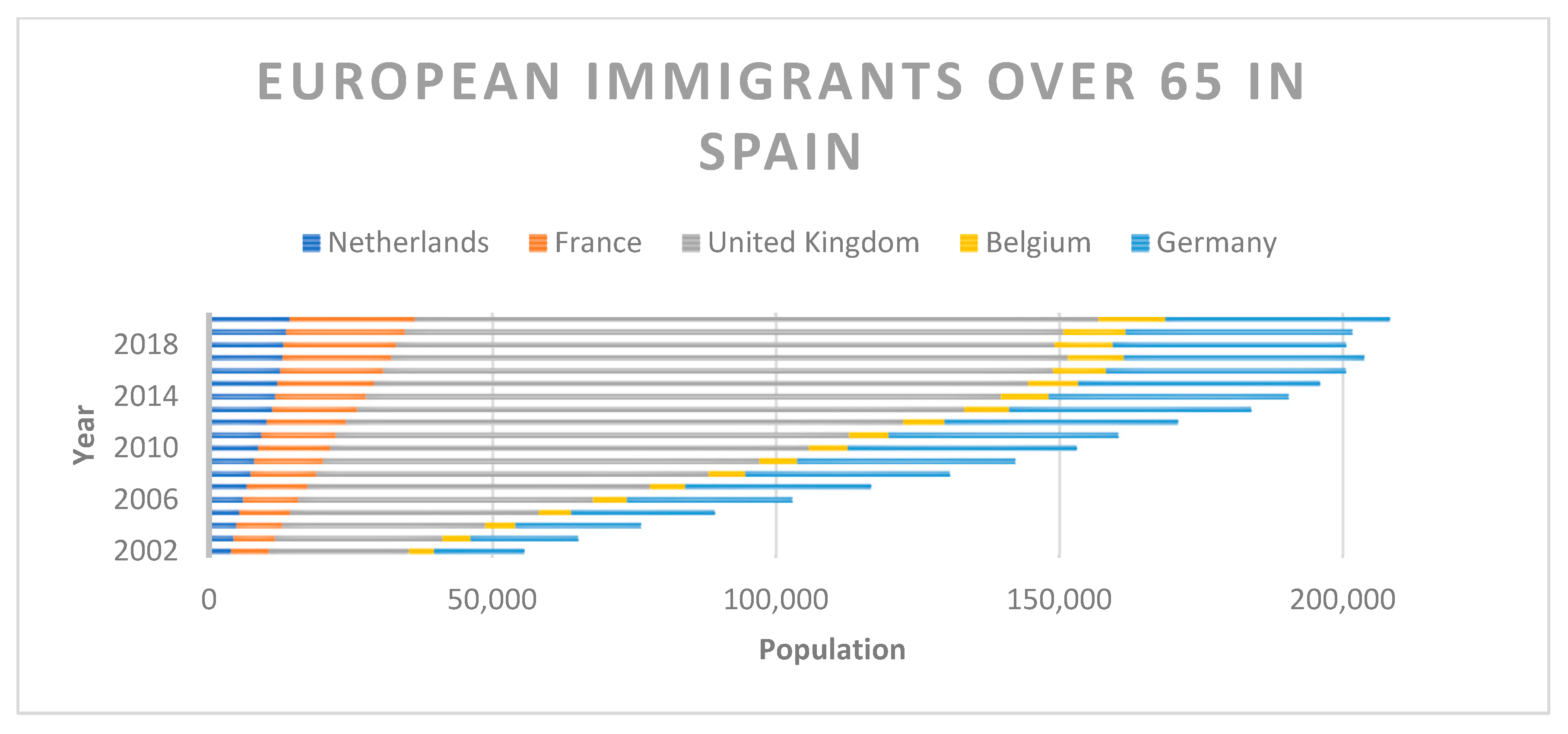

4.1. General Panorama of European Retirement Places

- Retirement migration is a spatially concentrated phenomenon and European Retirement Places are quite stable along the years. The provinces where our municipalities are located are known for being IRM destinations since the 1990s.

- The presence of non-Spanish elderly people is unusual in other areas of the country. Although 10% of residents in Spain have a foreign nationality, the percentage falls to 3% among those over 65 years old. The province of Madrid (where the Spanish capital is located) features 13% foreign residents, but only 2% of residents over the age of 65 have a foreign nationality.

- An additional interesting result that one can derive only by looking at the list of European Retirement Places is that in many places, the share of Europeans among the elderly is well above 30%. Considering that our data are, for sure, under-estimating the real number of elderly foreigners, our results point to the existence of many Spanish municipalities where retirement migrants are a very relevant group in size.

- 4.

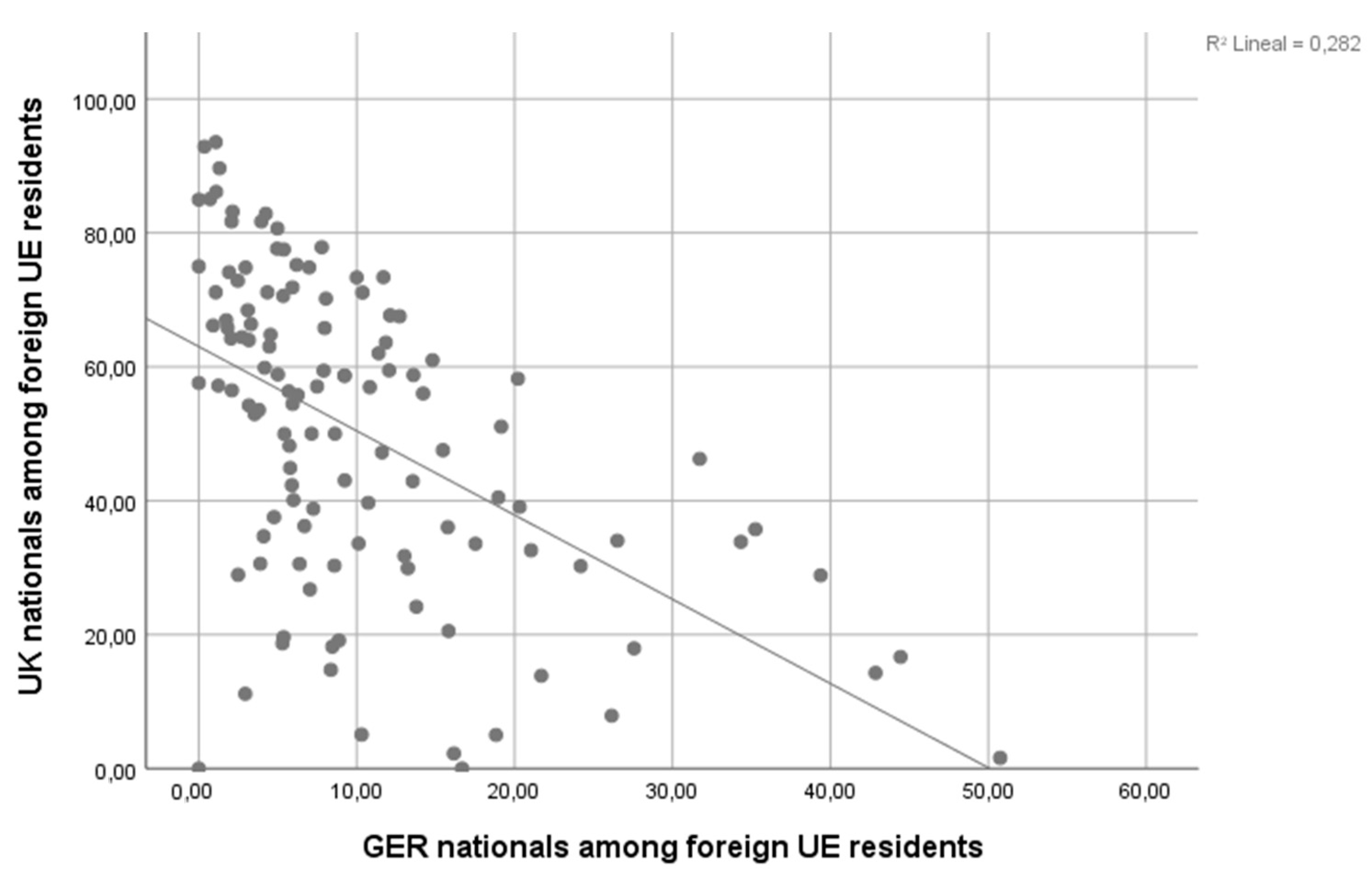

- Our data provide some confirmation not only for the spatial concentration of retirement migration but also for a tendency to cluster by nationality. In Figure 2 we can see that there are ‘British spots’ and ‘German spots’, and although this is by no means a radical separation. It is interesting to note that places where more than 60% of the foreign residents are from the UK tend to have very little German residents (less than 10%) and vice versa, places where German residents are substantial (more than 30%) tend to have less UK residents.

4.2. European Elderly as Users of Local Social Services

It is that they hardly come because they are self-sufficient, they aren´t demanding Social Services, they protect each other. They usually help each other, between friends. (…) They aren´t a group that usually request aid, we´ve had a case, but just once.

If they have money, they hire people from their community, well-known professionals. If they don´t have financial resources, then they come to Social Services and request the service of “home help” for cleaning, etc. And also [they demand help with] Dependency [claiming care support to the SAAD program in case of dependency] and Registration procedures.

(…) We learn of the existence of these people when they claim dependency benefits. They become disabled, they find themselves alone, and we learn about their situation by a neighbor or by someone else that contacts us. Before that, they never approach the Social Services.

Q. Is there a common pattern regarding the needs of elderly Europeans?

What we do most is Information Service. We process the “Andalucía 65 card” [discount card for those over 65]. Of every 10 cards, half are for English people. And especially issues related to Dependency. Of the 200 new applications [this year], 8–10% come from this group. What we do most is Dependency. They lose autonomy, and then is when they really come to us. Disability and everything related to technical aids.

Q. The older Europeans you have cared for, what kind of needs did they have?

Dependency problems, need for Home Assistance… They are alone; they do not have a family. They arrived [to Spain] when they were young, they were renting their homes… but they have grown older, with alcoholism problems, they are dependent people, they have run out of money… with non-contributory pensions. Alcohol 1, physical decline… They need help because they are uprooted.

Q. What is the most difficult thing to manage in these cases?

A. With the language barrier, the most complicated thing is to manage the Dependency application, because you have to ask for more documentation, medical reports, … the rest of things do not present problems, it is pure bureaucratic management, they [elderly Europeans] make easy requests.

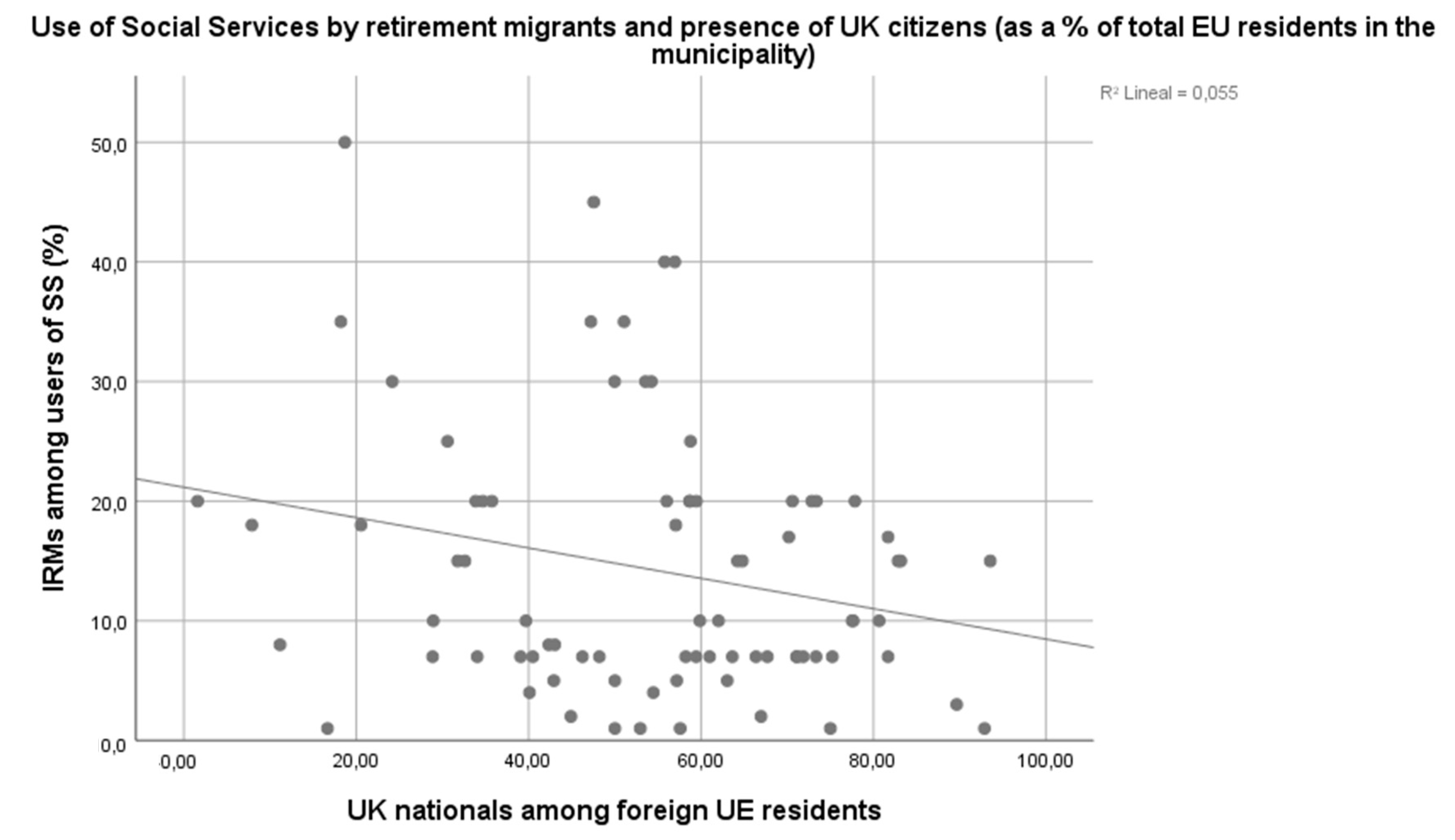

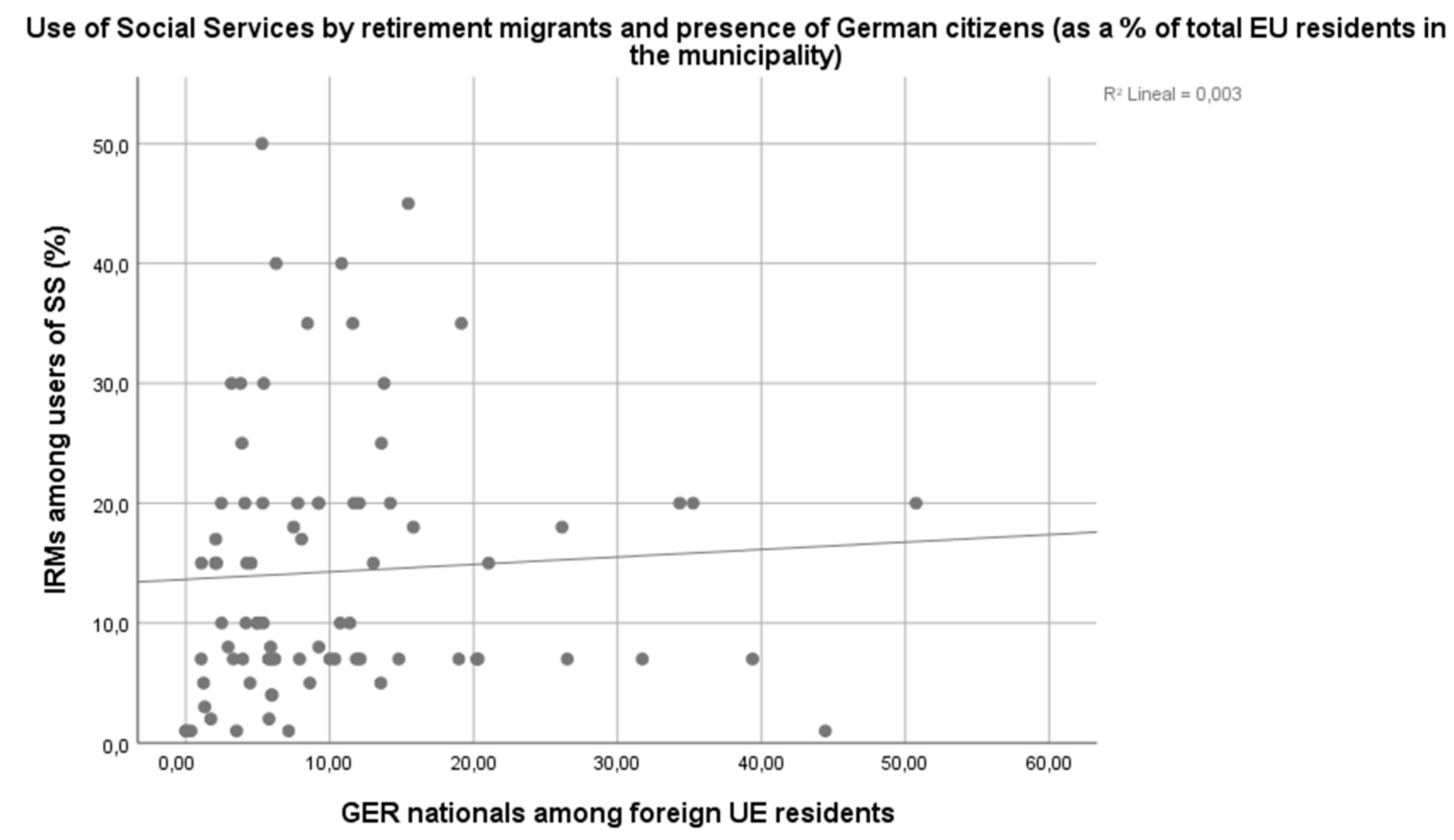

4.3. Empirical Evaluation of Hypotheses

4.4. Alternative Explanation for the Differential Impact of Retirement Migration on Local Social Services

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The issue of some retirement migrants having alcohol problems has been mentioned in other interviews and is also present in previous studies but we would need much more research to actually evaluate the extent of the problem. Stereotypes about Germans, English, and Nordic people as heavy drinkers may be at play. Some previous studies mentioning the issue: [17,18,51]. |

References

- Jurdao, F.; Sánchez, M. España: Asilo de Europa (Spain: Asylum of Europe); Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, M.; O’Reilly, K. Migration and the search for a better way of life: A critical exploration of lifestyle migration. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 57, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnes, A.M.; Friedrich, K.; Kellaher, L.; Torres, S. The Diversity and Welfare of Older Migrants in Europe. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Díaz, M.A.; Rodríguez, V. La Migración Internacional de Retirados en España. Limitaciones de las fuentes de información. Estud. Geográficos LXIII 2002, 63, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo, F. International Retirement Migration: Retired Europeans Living on the Costa Del Sol, Spain. Popul. Rev. 2004, 43, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, R. Residencia y vinculación de los retirados extranjeros. Una aproximación a los gerontoinmigrantes europeos en España. In La Residencia de Los Gerontoinmigrantes: Derechos y Obligaciones de Los Jubilados Extranjeros en Los Lugares Europeos de Retiro; Echezarreta Ferrer, M., Echezarreta Ferrer, M., Eds.; Tirant lo Blanch (Tirant monografías, 1024): Valencia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Díaz, M.A. Retiring to Spain: An Analysis of Differences among North European Nationals. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2006, 32, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R. Atractivo de España para los jubilados europeos: Del turismo a la gerontoinmigración. Panor. Soc. 2012, 16, 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, B.; Graham, M.S.D.; Mehmet, M. Little Norway in Spain: From Tourism to Migration. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karisto, A. Coping with Antinomies of Taste. Eating habits of Finish Retirement Migrants in Spain. In Nordic Seniors on the Move; Blaakilde, A.L., Nilsson, G., Eds.; Lunds Universitet: Lund, Sweden, 2013; pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, R.; Mantecón, A. La migración residencial de noreuropeos en España. Convergencia. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2013, 20, 219–245. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerlund, U. The Best of Both Worlds. Aspirations. Drivers and Practices of Swedish Lifestyle Movers in Malta. Ph.D. Dissertation, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Conradson, D.; Latham, A. Transnational urbanism: Attending to everyday practices and mobilities. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2005, 31, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibler, K.M.; Taltavull, P.; Casado-Díaz, J.M.; Casado-Díaz, M.A.; Rodríguez, V. Examining Retirement Housing Preferences Among International Retiree Migrants. Int. Real Estate Rev. 2009, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, H. Volunteering in retirement migration: Meanings and functions of charitable activities for older British residents in Spain. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1374–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavanas, A.; Calzada, I. Multiplex migration and axes of precarization: Swedish retirement migrants to Spain and their service providers. Crit. Sociol. 2016, 42, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavanas, A. Swedish Retirement Migrant Communities in Spain: Privatization, informalization and moral economy filling transnational care gaps. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 2017, 7, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Hardill, I. Retirement migration, the ‘other’ story: Caring for frail elderly British citizens in Spain. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giner, J.; Simó, C. El Retorno de los Retirados Europeos: Estudio sobre la Marina Alta. In Turismo, Urbanización y Estilos de Vida; Mazón, T., Huete, R., Mantecón, A., Eds.; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; pp. 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Giner, J.; Hall, K.; Betty, C. Back to Brit: Retired British migrants returning from Spain. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2016, 42, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, A. The transnational lives of Finnish retirees in Torrevieja. Matkailututkimus 2017, 13, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gavanas, A.; Calzada, I. Swedish retiree migrants in Spain: Mobility and elderly care in Ageing Europe. In Family Life in an Age of Migration and Mobility; Palenga-Möllenbeck, E., Kilkey, M., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2015; pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Parreño-Castellano, J.; Domínguez-Mujica, J. Working and retiring in sunny Spain: Lifestyle migration further explored. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2017, 65, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Social Protection without Borders? The use of social services by retirement migrants living in Spain. J. Soc. Policy 2017, 47, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, R.; Fokkema, T.; Nedelcu, M. Introduction. Ageing as a migrant: Vulnerabilities, agency and policy implications. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino, E.; Moreno-Fuentes, J. Desafíos del Estado de Bienestar en Noruega y España. Nuevas Políticas Para Atender a Nuevos Riesgos Sociales; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-309-6557-1. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi, W.; Palme, J. The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 63, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibfried, S. Towards a European welfare state? In The Welfare State Reader; Pierson, C., Castles, F.G., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992; pp. 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, M. The “Southern” model of welfare in social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1996, 6, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, G. Classifying welfare states: A two-dimension approach. J. Soc. Policy 1997, 26, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L. Bienestar mediterraneo y supermujeres. Rev. Española Sociol. 2002, 2, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, L.; Marí-Klose, P. Youth, family change and welfare arrangements. Eur. Soc. 2013, 15, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, C.H.; Jacobson, D.; Antonieou, E.; MCMullan, C. Welfare regime, welfare pillar and Southern Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2014, 24, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, M.; Künemund, H.; Vogel, C. Shrinking Families? Marital Status, Childlessness, and Intergenerational Relationships. In First Results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (2004–2007). Starting the Longitudinal Dimension; Börsch-Supan, A., Ed.; Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging: Mannheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Attias-Donfut, C.; Ogg, J.; Wolff, F.C. European patterns of intergenerational financial and time transfers. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, M.; Pavolini, E. Unequal Inequalities: The Stratification of the Use of Formal Care Among Older Europeans. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 72, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, A.; Zentai, V. Long-Term Care and Gender Equality: Fuzzy-Set Ideal Types of Care Regimes in Europe. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvó-Perxas, L.; Vilalta-Franch, J.; Litwin, H.; Mira, P.; Garre-Olmo, J. A longitudinal study on public policy and the health of in-house caregivers in Europe. Health Policy 2021, 125, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; McKee, M. Health and social fields in the context of lifestyle migration. Health Place 2012, 18, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klekowski von Koppenfels, A. Diaspora Policies, Consular Services and Social Protection for German Citizens Abroad. In Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 2); Lafleur, J.M., Vintila, D., Eds.; IMISCOE Research Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson Nyhammar, A.; Olsson, E. Diaspora Policies, Consular Services and Social Protection for Swedish Citizens Abroad. In Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 2); Lafleur, J.M., Vintila, D., Eds.; IMISCOE Research Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Consterdine, E. Diaspora Policies, Consular Services and Social Protection for UK Citizens Abroad. In Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 3); Lafleur, J.M., Vintila, D., Eds.; IMISCOE Research Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government: UK Benefits If You’re Going Or Living Abroad. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/uk-benefits-abroad (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Huete, R.; Mantecón, A. Residential tourism or lifestyle migration: Social problems linked to the non-definition of the situation. In Controversies in Tourism; Moufakkir, O., Burns, M.P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, J.; Parreño, J.M. Trabajadores y retirados. La flexible condición de los migrantes del oeste y norte de Europa en los destinos turísticos de España. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2014, 64, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R. Sanidad en la España de Retiro: De atractivo para la gerontoinmigración a preocupación y movilización política por el "brexit". In Sanidad Transfronteriza y Libertad de Circulación. Un Desafío Para Los Lugares Europeos de Retiro; Elsa, M.Á., Ed.; Tirant lo Blanch, págs: Valencia, Spain, 2018; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- OReilly, K. The British on the Costa del Sol. In Transnational Identities and Local Communities; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hardill, I.; Spradbery, A.; Arnold-Boakes, J.; Marrugat, M.L. Severe health and social care issues among British migrants who retire to Spain. Ageing Soc. 2005, 25, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echezarreta, M. El Lugar Europeo de Retiro. Indicadores de Excelencia Para Administrar la Gerontoinmigración de Ciudadanos de la Unión Europea en Municipios Españoles; Editorial Comares: Granada, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, R.; Mantecon, A.; Estevez, J. Challenges in lifestyle migration research: Reflections and findings about the Spanish crisis. Mobilities 2012, 8, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RESIDENTS AGED 65+ | N Municipalites | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly foreigners as a % of the elderly | 30–40% | 48 | 40.3 |

| 41–50% | 24 | 20.2 | |

| +50% | 47 | 39.5 | |

| Total | 119 | 100.0 | |

| Number of Municipalities | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| European elderly as % of Social Services claimants | 0–10% | 43 | 53.8 |

| 11–20% | 24 | 30.0 | |

| 21–30% | 6 | 7.5 | |

| More than 30% | 7 | 8.8 | |

| Total | 80 | 100.0 | |

| Elderly Foreigners in the Municipality (% of Local Elderly) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–40% | 41–50% | +50% | |||

| European elderly as % of Social Services claimants | 0–10% | 19 | 7 | 17 | 43 |

| 61.3% | 50.0% | 48.6% | 53.8% | ||

| 11–20% | 9 | 5 | 10 | 24 | |

| 29.0% | 35.7% | 28.6% | 30.0% | ||

| 21–30% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | |

| 3.2% | 14.3% | 8.6% | 7.5% | ||

| More than 30% | 2 | 0 | 5 | 7 | |

| 6.5% | 0.0% | 14.3% | 8.8% | ||

| Total | 31 | 14 | 35 | 80 | |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calzada, I.; Páez, V.; Martínez-Cassinello, R.; Hervás, A. The Best Welfare Deal: Retirement Migrants as Welfare Maximizers. Societies 2023, 13, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13040102

Calzada I, Páez V, Martínez-Cassinello R, Hervás A. The Best Welfare Deal: Retirement Migrants as Welfare Maximizers. Societies. 2023; 13(4):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13040102

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalzada, Inés, Virginia Páez, Rafael Martínez-Cassinello, and Andrea Hervás. 2023. "The Best Welfare Deal: Retirement Migrants as Welfare Maximizers" Societies 13, no. 4: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13040102

APA StyleCalzada, I., Páez, V., Martínez-Cassinello, R., & Hervás, A. (2023). The Best Welfare Deal: Retirement Migrants as Welfare Maximizers. Societies, 13(4), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13040102