Abstract

The importance of achieving an inclusive education to ensure parity and equality between genders is a worldwide challenge. Consequently, it is essential to rethink the various places and spaces within the school environment where gender inequalities are produced. Physical education is one of these spaces which has been identified as a problematic area in the literature. In order to address this issue and respond to the needs identified in the research, this systematic review presents action initiatives aimed at applying certain teaching strategies highlighted in the study. The PRISMA method was used to review 274 studies which explore this topic at various levels of education, emphasizing the need for coeducational teaching of physical education and the necessity of proposing motivational tasks for both sexes. In particular, results show that some studies have focused on the need for physical education teachers to be aware of potential gender-biased structures when developing curricula, approaches and materials. Other research has highlighted that in order for physical education classes to be inclusive, equitable opportunities must be provided for all students to participate. In addition, strategies should be implemented which promote positive attitudes towards physical activity by addressing any underlying gender stereotypes and by breaking down traditional boundaries that exist between genders. In conclusion, this systematic review has identified a number of teaching strategies which could help teachers create an equitable learning environment within physical education classes. This could subsequently lead to greater success in achieving an inclusive education which promotes parity and equality between genders.

1. Introduction

Education and training are essential for personal development and for creating a more competitive and equitable knowledge-based society [1]. Through education, it is possible to foster areas of improvement and progress for individuals and the mindset of society [2]. One of the topics that has been gaining more significance is gender equality. This is an issue of great importance in the formal education system, as equal opportunities for both men and women are essential for achieving parity [3]. Therefore, the educational system must work to overcome sexist attitudes and ensure that gender equality is one of the fundamental values citizens need to embrace in the 21st century [4]. Schools should promote an inclusive and democratic education that respects the principles of equality, fairness, and social justice for all members of the community [5].

The magnitude and effects of the gender awareness topic have caused it to become highly relevant in today’s society, prompting educational centres to prioritize the treatment of it throughout the school year [6]. In recognition of this, many organizations and institutions have adopted important dates such as 8 March (International Women’s Day) and 25 November (International Day Against Violence Against Women) as days of activism and reflection on the movement [7]. Equality should not be treated as merely a democratic principle, but rather as an essential and compulsory goal of educational organizations, schools, public institutions, and institutes [8]. It is through these foundations that students can learn to reject any form of discrimination and abuse and internalize the values of equality [4]. The Education for All Program [9] has made it a priority to invest in achieving parity and equality between genders, an idea that is supported by the values of sport and physical education [10]. Thus, in order for these values to be effectively transmitted to students, it is essential that the teaching of physical education be approached carefully, to ensure real equality in the classroom and beyond.

Despite this, reflecting on the need for students to learn to reject any form of discrimination and abuse and internalize the values of equality is shown to be especially true when considering gender equality, as can be seen from both Kaba [11] and Cretan & Turnock [12]. Kaba’s research shows that although African American women have experienced the most severe forms of both racism and gender discrimination, they are still becoming a model minority in terms of college enrolment rates and other life outcomes. On the other hand, Cretan & Turnock [12] highlight the case of Roma people in Romania who struggle to become integrated into mainstream society due to their identity, which implies separation from a modernizing ethos. Therefore, this points to a clear necessity for students to learn about these issues in order to understand why certain individuals or groups are marginalized, discriminated against, or marked as “the other”. Students should also receive education on how they can actively fight against such discrimination by internalizing values of equality such as respect for all individuals regardless of their race, ethnicity, religion, or gender. Only then will students be able to truly reject any form of abuse and discrimination that they may encounter.

Advancing on the topic of this research, the literature reveals that there is a lack of equality in the fields of physical education and sport, both in terms of participation and opportunity. Studies have shown that gender disparities in physical activity and sport start early, particularly among 12- or 13-year-olds, and that these inequalities can continue into adulthood [13,14,15,16,17]. Teachers have the potential to influence individuals’ sports habits and prevent gender inequality from forming [17]. Addressing this issue requires synthesizing the existing literature in an accessible and affordable way, particularly in non-academic settings, and this study seeks to do just that.

Physical education (PE) is a field of study and practice that promotes physical activity, health, and wellbeing through the implementation of movement-based curricula. It is often taught to children and adolescents in educational settings but can also be applied to people of all age groups. This systematic review focuses on the topic of gender equality in PE from 2000 to 2020. Selection criteria included original scientific articles published in their entirety, peer-reviewed articles related to gender equality in PE, experimental studies, and qualitative studies. The review aimed to identify strategies used by teachers and researchers when dealing with gender equality in school interventions with students aged 6–14 years old (average 11.33). Additionally, research interventions and field work conducted in universities and schools for future teachers and experienced professionals aged 18–58 were included.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Key Concepts in the Fight for Gender Equality

In order to understand gender equality in physical education, it is essential to consider certain key terms. Malavé [17] and Ferro, Azurmendi, and Leunda [18] have identified the following concepts as essential for a better understanding of this subject matter: the principle of equal treatment, sex, gender and gender difference, discrimination based on gender, the gender gap, positive actions, and inclusive, non-sexist communication.

The principle of equal treatment implies the lack of any direct or indirect discrimination on the basis of gender [18]. Sex is a categorization based on biological traits while gender is a sociological categorization. Discrimination based on gender refers to unequal treatment and opportunities given to certain people due to their gender. The gender gap refers to disadvantages faced by women in comparison to men due to historical differences based on beliefs about femininity and masculinity. Positive actions are temporary measures taken to equalize the involvement of women in society. Inclusive, non-sexist communication gives visibility to both genders regardless of the channel used (visual, oral or written).

It is important for teachers and media outlets to be aware of these terms in order to avoid the ignorance of existing discrimination. This ignorance can lead to people not taking sides in placating it or not realizing the impact their actions can have on others [18].

2.2. Physical Education and Gender Inequality

As shown in the introduction section, during the school years, cases of inequality are still considered to exist in physical education. Examples of this, according to the statements of authors such as Ramos and Hernandez [19], are usually given when teachers do not make any kind of intervention when organizing groups during sessions and activities, with the result that usually non-mixed groups are ones that predominate, meaning that between boys and girls, there is practically no interaction. This, coupled with the typical implementation of physical and sports activities of predominantly male interest in contrast to other activities that, based on various studies, generate greater interest in the female population, is another area where there should be greater development along the lines of gender equality within the subject [20,21,22].

Given these inequalities presented by authors such as Díaz de Greñu and Anguita [23], who claim that much of the teaching staff still has a twentieth-century mentality and maintains certain prejudices associated with a historical system of sex/gender, authors such as Devís, Fuentes Sparkes [24] and Piedra, García-Pérez, Fernández-García and Rebollo [25] stress the importance of physical education teachers receiving specific training in gender equality and that, given the current curriculum which is closer to male preferences [20], proposals should be drawn up which consider the needs of both male and female students.

Another topic where authors such as Alfaro, Bengoechea and Vázquez [22] are concerned is the oral language that is usually used in the classroom, which is usually sexist, using expressions that praise virtues of a male nature when it comes to providing any positive reinforcement, underestimating and diminishing the visibility of girls, and causing them not to feel involved. In view of this, Subirats [26], indicates that it will be essential, consequently, that teachers modify certain habits, and that they give greater relevance to the motivational climate, orienting it towards the task and not towards the ego, since while the ego-oriented motivational climate would favour a perception of discrimination, the task-oriented motivational climate would favour a better perception of equality in the students.

Fortunately, in recent years, there has been an increasing tendency for teachers to be concerned about these kinds of issues and to accept changes in gender equality issues and, therefore, they are beginning to transmit them to students during their teaching [27]. For all these reasons, and once the presence of gender inequality has been proven, which is still very notable, both in society and in physical education, it is still a field that should be studied.

Moreover, Alfaro, Bengoechea and Vázquez [22] put stress the language used in the classroom, which is usually sexist, especially when it comes to providing any positive reinforcement. This type of language tends to praise gender-related virtues and underestimate and diminish the visibility of girls, making them feel left out. Subirats [26] argues that teachers must take responsibility for modifying certain habits and give greater relevance to the motivational climate, orienting it towards the task and not towards the ego. An ego-oriented motivational climate would only encourage a perception of discrimination but encouraging a task-oriented motivational climate would help promote better perceptions of equality in students. Taking all this into account, it is clear that physical education teachers should strive to create an inclusive environment that helps guarantee gender equality in the classroom.

Fortunately, this change is beginning to take place, as teachers are becoming more aware of these issues and are increasingly willing to make changes [16]. It is essential that these changes continue so that physical education classes can be a space where both boys and girls can feel included and valued for their efforts.

3. Methods

In the present study, the decision was taken to carry out a systematic review following the approach taken by researchers such as Fernández-Ríos and Buela-Casal [28], retrieving all the scientific literature published about the area. Due to the great variability of data, evaluation instruments, and sample size, recommendations by authors such as Wright, Brand, Dunn, and Spindler [29], Slavin [30], or Lucas, Baird, Arai, Law, and Roberts [31] meta-analysis were ruled out, and a narrative approach were followed, with the sole purpose of favouring a greater verbal interpretation and the production of new ideas. To favour the systematization of the data finally presented, a systematic analysis of the literature was chosen, following the PRISMA method.

3.1. Search Strategies

To congruently and adequately reflect the literature focused on physical education from a gender perspective, specifically on the fight for gender equality, a detailed analysis was carried out in which various processes of searching for information were carried out.

- (1)

- Various searches were carried out on those search engines considered to be of the greatest importance and prestige in the field of scientific dissemination, such as the Web of Science (WOS) and the SCOPUS data collection. During these searches, all references dealing with the teaching of physical education through various specific actions, activities, and methodologies dealing with gender equality were reviewed, using the following search descriptors for this selection: “gender equality”, “physical education”, “gender equity”, “gender equality”, “physical education” and “gender inequality”, producing a combination of these with the sole purpose of facilitating the configuration of the search phrases.

- (2)

- Journals related to the objective and main line of the study were examined manually (International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, Journal of Sport Behaviour and Psychology of Sport & Exercise, Exceptional Education Quarterly, Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, Journal of Sport Sciences, Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, International Journal of Sport Psychology, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, Sciences, Educación XXL, Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte, Educación Física Digital, Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, Revista de Educación Física, Revista Internacional de Sociología (RIS), and Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, Apunts: Physical Education and Sport).

- (3)

- Various specialised databases were consulted for doctoral theses, mainly Teseo and Proquest Dissertation & Theses Full Text.

- (4)

- With the aim of accessing those bibliographies whose accessibility is very difficult and which have not been published through the usual channels, databases aimed at grey literature were analyzed, such as SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) and PsycExtra (American Psychological Association).

- (5)

- In order to select and locate all the novel studies, which had not been previously selected in the initial search process, a bottom-up review of the retrieved literature was carried out.

3.2. Selection of Studies

Once the population framework of the research had been concluded, it was decided to temporarily limit the publication dates of the articles recovered in the search, from the year 2000 to 2020, that is to say, the last 20 years, since this is a subject which, although it has been gaining strength in recent years, has been advancing for many years and it was considered very useful to analyse the strategies carried out during this time framework in order to be able to evaluate the change or progress that has been made. The search was limited by selecting as part of the work those articles located within the publications of the “social science” domain, indicating as a preference the research areas of “education educational research” and “sport sciences”. To limit the sample size of the research, the following selection criteria were chosen: (1) original scientific article published in its entirety, (2) peer-reviewed article, (3) scientific articles where the subject of study is carried out, this being gender equality in physical education, (4) experimental studies, and (5) qualitative studies. In the initial phase, the titles, summaries, and introductions of the publications were reviewed. Once this process had been completed, the second phase was carried out, in which the full texts of the remaining research were analyzed and, in the final phase, all those documents that were related to the subject were selected and dealt with the aspects mentioned above from various perspectives.

4. Results

4.1. Population and Sample

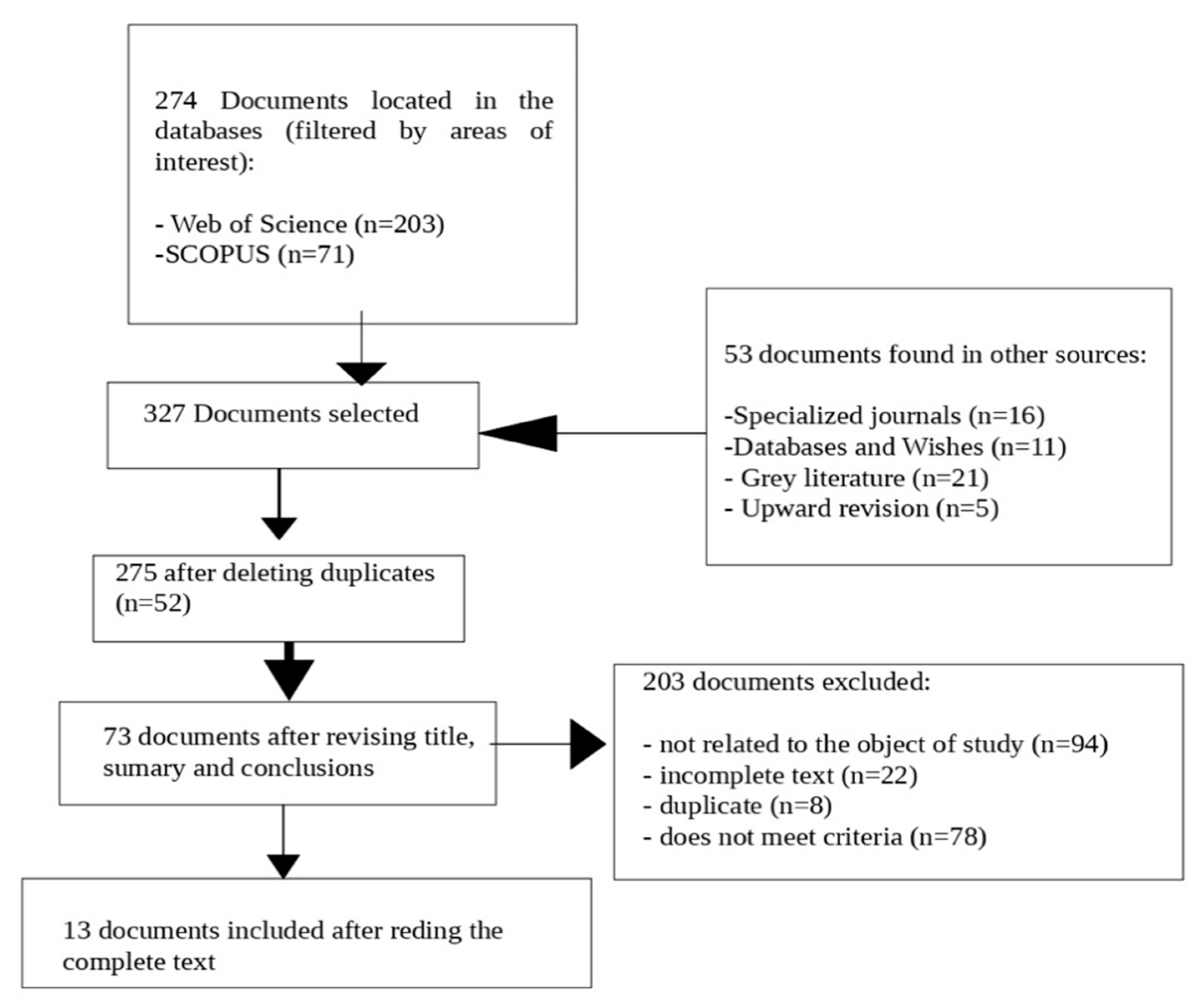

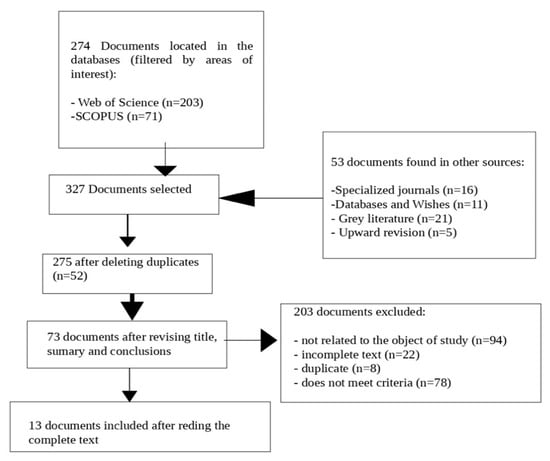

Based on the above, 327 potentially relevant documents were located. After this, duplicate studies (n = 53) were eliminated when applying the inclusion criteria, so the population framework of our research was reduced to a total of 274 research papers. Once we had gone through the previous processes, all those studies that did not meet the criteria set at the beginning were excluded when reviewing titles, abstracts, and introductions (n = 201). After this, those studies that were not valid when carrying out a complete reading of the text were eliminated (n = 48). Finally, only those studies were selected that were in line with the research topic or that were best adapted to it, as they generated relatively new proposals. Therefore, finally, 13 scientific papers were obtained. This is reflected in the following image that summarizes the processes previously outlined (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. Source: Own elaboration.

4.2. Potentially Moderating Outcome Variables

Two large heterogeneous groups were formed from the selected studies. The first group was composed of research approaches which focused on collecting and presenting strategies used by teachers and researchers when dealing with gender equality in school interventions with students. The second group involved an intervention project and collection of assessments regarding the use of the subject by experienced teachers, future teachers, physical activity and sports sciences degree students, and master’s degree students in teaching.

4.2.1. Gender Equality in Physical Education in Schools

In the first group of research studies, there are six studies that include interventions and field research conducted in schools on gender equality in physical education. This population consists of 2859 high school and college students aged between 6 and 14 years with an average age of 11.33. The breakdown is 2059 girls, 630 boys, and 170 with no gender specified. The characteristics of these studies can be found in the Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Characteristics of group 1 of the studies found through the search process described [32,33,34,35,36,37].

This group of studies examines the teaching work and attitudes of students in physical education. Factors such as motivation, aspects influencing the environment, gender relations within the classroom, and student perception are investigated. Pelegrin et al. [33] researched these factors with the aim of finding a way to promote gender equality. Rodríguez and Miraflores [35] and Granda et al. [36] designed instruments and approaches to try to overcome stereotypes and inequalities in student perception, while Gil and Etxebeste [37] analyzed teachers’ work with a view towards promoting changes in favour of greater gender equality. The Table 2 summarizes these investigations regarding objectives, methodology, results, and conclusions reached by them:

Table 2.

Objectives, methodology, results and conclusions reached in the studies of the first group [32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

The purpose of this paper was to review the literature and analyse the effects of interventions in physical education classes to promote gender equality among boys and girls. The results of this group of studies analyzed demonstrate that there is potential for these interventions to increase the enjoyment of physical education among girls, as well as reduce sexist behaviours amongst children of both genders.

Barr-Anderson et al. [32] found that activities presented in a way that is attractive to girls can help develop greater confidence in traditionally male-dominated activities, potentially leading to an increase in the enjoyment of physical education among girls. Furthermore, Pelegrín et al. [33] argued that interventions in physical education classes have had a positive influence on opinions on gender equality, leading to a reduction in sexist attitudes and behaviours among school children of both genders.

Del Castillo-Andrés et al. [34] suggested that gendered behaviours are related to motivational factors such as attitude towards PE, interest in sports, health, and body image; they also highlighted the importance of introducing tasks into PE sessions which are attractive for both boys and girls. Rodríguez y Miraflores [35] underlined high-quality teaching as a necessity for promoting gender equality within the classroom, whilst Granda et al. [36] stated the need for promoting respect between students from kindergarten onwards when it comes to challenging gender stereotypes within physical education lessons. Lastly, Gil y Etxebeste [37] argued that if teachers are able to maintain control over activities, then mixed projects with shared leadership between boys and girls can be encouraged; however, if left unmonitored, then traditional gender stereotypes may be reinforced through self-segregation among boys and girls during their participation in PE classes.

To sum up, the results of this group of studies suggest that there is great potential for interventions within physical education sessions which can help promote gender equality amongst school children; by encouraging traditional male-dominated activities presented attractively towards female students and maintaining control over the activity flow teachers can help foster an environment where both genders feel respected and valued equally during participation in physical education lessons—ultimately leading towards an increased enjoyability factor while learning key skills associated with physical exercise.

4.2.2. Gender Contents in Teacher Training for Physical Education

The second group of studies consists of seven research interventions and field work on gender equality in physical education, conducted in universities and schools for future teachers and experienced professionals. This group had a total population of 484 students and 565 teachers whose ages ranged from 18 to 58 years. The subjects included in these studies comprised a total of 181 women, 258 men, and 610 unspecified individuals. These characteristics are specified in the Table 3 below:

Table 3.

Characteristics of group 2 of the studies found through the search process described [25,39,40,41,42,43,44].

Group two examines teaching work and the training future teachers receive during physical activity degrees and master’s degrees in teaching. Fernández and Piedra [39], Prat-Grau and Flintoff [41], and Piedra et al. [41] studied the effect of university training on attitudes and strategies future teachers apply to gender equality. Camacho-Miñano and Girela-Rejón [43] and Hortiguela and Hernando [44] devised strategies to improve this training, which was previously evaluated by the authors mentioned. Lastly, Piedra et al. [25] researched what attitudes teachers had towards equality measures proposed by other authors. These studies provide a great deal of information about methodology, objectives, results, and conclusions; a brief account of these can be seen in the Table 4 below:

Table 4.

Objectives, methodology, results and conclusions reached in group 2 studies [25,39,40,41,42,43,44].

The results of this group of papers indicate that there is a need for training in gender issues and coeducation in physical education, which will help promote gender equality and combat heterosexism and homophobia. Fernández y Piedra [39] argued that training in coeducation can have a positive effect on attitudes towards equality, as opposed to students who do not receive such training. Patinet-Bienaimé y Cogerino [45] further established a link between the quality of care given to achieving gender equality, and the diversity of intentions pursued. Prat-Grau y Flintoff [41] found that many teachers did not believe there was still a need for mainstreaming gender issues but advocated for specific subjects to address these matters during physical education training plans.

Piedra et al. [42] noted the generalization of heterosexist behaviour, as well as students having experienced or witnessed situations of inequality or homophobia in PE classes. To counteract this lack of awareness among teachers, they proposed strategies to raise awareness and influence knowledge production about these topics in PE classes. Piedra et al. [25] found evidence of adaptive attitudes towards inequalities among teachers but recognized that formal and continuous training was needed to further improve their attitudes towards gender issues. Camacho-Miñano y Girela-Rejón [43] reported positive feedback from students about receiving some form of gender training during their sports degree program, with 78.4% considering it “fairly” or “very” relevant, and 89.2% finding it “fairly” or “very” useful for their future professional activity, suggesting higher levels of involvement and awareness after receiving such instruction than before it was introduced into their curriculum. Finally, Hortiguela y Hernando [44] argued that a methodological change is necessary so that PE can be used as an ideal tool for work on coeducation and gender equality, breaking away from traditional models based on individual performance which limit social possibilities.

Overall, then, the group of articles analyzed has provided many arguments which suggest teaching staff should be provided with appropriate strategies to promote gender equality in physical education classes by providing them with formalized instruction on how to do so effectively, breaking away from traditional methods based on individual performance which limit social possibilities, and allowing physical education to become an ideal tool for work on coeducation and gender equality.

5. Discussion

Our study sought to analyze the current situation and approach to gender equality in physical education, investigating the attitudes and opinions of students in schools and universities as well as teachers. After reviewing 13 studies that met our criteria for inclusion, it became clear that there was a need to create activities in physical education classes that are attractive to female students. Several authors have highlighted this need, including Blández, Fernández, and Sierra [20], García [21], and Alfaro, Bengoechea, and Vázquez [22]. The results showed that by providing tasks and activities that are presented in an attractive way for girls, their confidence, motivation, enjoyment, problem-solving skills, and self-control can be improved [37]. Therefore, it is necessary to provide strategies to bridge the existing gap between male-dominated activities and those that girls may find interesting.

Research conducted by Pelegrín et al. [33], Del Castillo-Andrés et al. [34], and Granda et al. [36] has found that boys generally have more sexist attitudes towards girls, which is based on traditional sexist beliefs towards women such as the perception of them as weaker, less skilled, and less intelligent. This is a result of inadequate education on gender equality, which is why it is essential to continue educating male and female students on these matters from a young age. Pelegrín et al. [33] observed positive results of their intervention where they gathered information about female and male athletes of little recognition and carried out tasks with mixed groups, which improved the students’ opinions on gender equality and decreased sexist behaviour in both genders. Del Castillo-Andrés et al. [34] concluded that such behaviour can be reduced if teachers orient sessions and activities towards the task rather than the ego, which Subirats [26] also found to be true. Therefore, it is clear that gender equality should be promoted in education in order to reduce gender discrimination and create a better motivational climate for students.

Additionally, the results of the selected studies [25,35,39,40,41,45] show that there is a generalization of sexist behaviour and gender inequality among physical education teachers. This lack of awareness has led to a sense of complacency regarding the issue of gender equality in the classroom. Consequently, it is necessary to raise the quality of teachers’ work and to train and raise their awareness of the gender perspective in order to promote and develop equality in the physical education classroom [24]. Furthermore, it is essential for teachers to be mindful that their behaviour and language will greatly influence students.

Furthermore, Piedra et al. [42] observed an alarming prevalence of heterosexist behaviour among students and noted many instances of inequality or homophobia in physical education classes. To combat this, they proposed strategies to increase awareness about these topics among teachers and influence knowledge production about them during physical education classes. Piedra et al. [25] then found evidence of adaptive attitudes towards inequalities among teachers but also recognized the necessity for further formal and continuous training in order for such attitudes to be effectively maintained in the future. It is clear then, that there is an urgent need for more comprehensive teaching on gender issues and coeducation within physical education curriculums across all educational institutions if we are serious about achieving true gender equality and eliminating heterosexism and homophobia from our classrooms once and for all.

The importance of appropriate training for promoting gender equality has been highlighted in several studies, such as those conducted by Fernández and Piedra [39] and Camacho-Miñano and Girela-Rejón [43]. The results of these investigations revealed a greater commitment and awareness on the part of students to a subject that initially did not generate much interest. Similarly, the introduction of a coeducation proposal in the research study yielded positive outcomes with an improvement in attitudes towards equality. Therefore, it is evident that such training is essential for future educators to ensure a more equitable society. Furthermore, Hortiguela and Hernando [44] have also noted that physical education can be a powerful tool for fostering gender equality. However, in order to effectively pursue this goal, it is necessary for instructors to make substantial methodological changes.

6. Implications for Policy-Making

The results of the studies discussed suggest that physical education classes must be designed in a way that is attractive to female students and that there needs to be an increased focus on gender equality, coeducation, and the elimination of heterosexism and homophobia. This suggests the need for evidence-based policies to ensure that physical education classes truly promote gender equality. Such policies should include appropriate training for physical education teachers, as well as formal and continuous training on gender issues. Evidence-based policy-making is essential in order to ensure that the decisions made are grounded in research, data, and evidence. This can help inform decisions about how best to address issues such as gender inequality within physical education.

Specific Action Proposal

In order to effectively promote gender equality within physical education classes, it is important for policy-makers to consider a few specific actions. Firstly, teachers should be provided with comprehensive training on gender issues so they are aware of what strategies they should employ in their classrooms [24]. Secondly, activities should be designed in such a way that they are attractive to female students [20,21,22]. Thirdly, students should be educated on the importance of gender equality from a young age [33,34,38]. Finally, teachers must be mindful of how their behaviour and language impact students’ attitudes towards gender equality [26].

Policy-makers should also prioritize strategies aimed at reducing heterosexist behaviour and homophobia amongst both teachers and students [42]. This can be achieved through increasing awareness about these topics among teachers by providing them with more comprehensive training on gender issues [24]. Policy-makers should also consider introducing coeducation proposals into physical education curriculums as these have been found to improve attitudes towards equality [43].

By implementing these specific actions into policy-making initiatives related to physical education classes, it is possible for us to create a more equitable society where all genders have equal access to resources and opportunities.

7. Conclusions

After thoroughly evaluating the results and conclusions from the studies included in this research, it is appropriate to establish these conclusions and present our opinion on the matter as a final judgement. It can be said that the goal of this study has been achieved, since in the research process an exhaustive and critical analysis of measures for gender equality in physical education has been completed. A great amount of bibliographical data was examined, and different points of view were identified; however, it can be seen that despite recent attempts to enhance gender equality in physical education, this subject is still lagging behind in terms of progress. This can be attributed to the militaristic background of sport, which prioritizes male-dominated activities. Therefore, it is important for teachers to create tasks and activities that potential female participants find attractive to increase their confidence and motivation. Educational institutions should also play an essential role by providing teachers with proper training concerning gender equality. Moreover, providing gender education from a young age is essential for this process to be shorter and for these ideas to penetrate more deeply into society.

To sum up, this study has shown that there is a need to create appropriate and attractive activities in physical education classes to bridge the existing gap between male-dominated activities and those that girls may find interesting. Additionally, it is essential to provide adequate education on gender equality and for teachers to be mindful that their behaviour and language can greatly influence their students. Furthermore, appropriate training for promoting gender equality is also necessary for both students and future educators. Physical education classes can be a powerful tool for fostering gender equality as long as instructors make substantial methodological changes. Ultimately, the aim should be to create a more equitable society that encourages gender equality.

In this matter, and based on the evidence presented, it is clear that a stronger commitment to gender equality in physical education is necessary, to ensure that students of all genders are able to participate and benefit from this critical aspect of education. All stakeholders must be aware of their roles in promoting gender equality and take active steps to bridge the existing gender gap in both educational practices and attitudes. Through increased training and awareness among teachers, appropriate activities for female students, and an increased focus on the task rather than ego, physical education can serve as an effective tool for fostering gender equality.

7.1. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations that should be taken into account. Firstly, this study was limited to the period 2000–2020, thus not taking into consideration studies that were conducted prior to this period. Secondly, the search was limited by selecting as part of the work those articles located within the publications of the “social science” domain, indicating as a preference the research areas of “education educational research” and “sport sciences”. Additionally, a narrative approach was used in favour of a meta-analysis due to the great variability in data, evaluation instruments, and sample size. This might have affected our ability to draw more concrete conclusions from our findings.

7.2. Further Lines of Research

Given these limitations, there is scope for further research in this area. Firstly, it would be important to conduct a longitudinal study involving data from before 2000 until 2020 so as to gain a better understanding of how gender equality has evolved over time in physical education and sports sciences. Furthermore, it would be useful to expand our search beyond “social science” domains and include other related domains such as health sciences or psychology, which could provide valuable insights into gender equality in physical education and sports sciences. Finally, conducting a meta-analysis instead of a narrative approach could provide more concrete evidence regarding gender equality in physical education and sports science fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.G. and L.G.P.; methodology, M.A.G.; software, M.A.G.; validation, M.A.G.; formal analysis, M.A.G. and L.G.P.; investigation, M.A.G. and L.G.P.; resources, L.G.P.; data curation, M.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.P.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G. and L.G.P.; visualization, L.G.P.; supervision, M.A.G. and L.G.P.; project administration, M.A.G. and L.G.P.; funding acquisition, M.A.G. and L.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is associated with the project funded by University of Granada, grant number INV-IGU 195-2022. But funding has being fully funded by the authors. The APC was funded by MDPI through reviewer vouchers, University of Granada IOAP program, and partially paid by authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created, but data treatment has been done according to “MDPI Research Data Policies” available at https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hoedl, E. Europe 2020 Strategy and European Recovery (Strategia Europa 2020 I Europejska Odbudowa). Probl. Ekorozw Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 6, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo, C. Aprender a enseñar para la sociedad del conocimiento. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2001, 12, 531. [Google Scholar]

- Anguita, R. El reto de la formación del profesorado para la igualdad. REIFOP 2011, 14, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Abellán, C.M.A. Actitudes del profesorado hacia la coeducación: Claves para una educación inclusiva [Teacher attitudes toward coeducation: Keys to inclusive education]. ENSAYOS. Rev. Fac. Educ. Albacete 2014, 29, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaiz, P. Escuelas eficaces e inclusivas: Cómo favorecer su desarrollo. Educ. Siglo XXI 2012, 30, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M. Perspectiva de Género y Políticas de Educación: La Necesidad de la Orientación Educativa Para una Coeducación Real. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grañeras, M.; Mañeru, A.; Martín, R.; de la Torre, C.; Alcalde, A. La prevención de la violencia contra las mujeres desde la educación: Investigaciones y actuaciones educativas públicas y privadas. Rev. Educ. 2007, 342, 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, M.E. La Igualdad También se Aprende. Cuestión de Coeducación; Narcea, S.A., Ed.; Ediciones: Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Educación Para Todos en 2015 ¿Alcanzamos la Meta? UNESCO: París, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, K. Researching disibility and inclusive education: Participation, construction and interpretation. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1997, 1, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, A.J. Race, Gender and Progress: Are Black American Women the New Model Minority? J. Afr. Am. St. 2008, 12, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Turnock, D. Romania's Roma Population: From Marginality to Social Integration. Scott. Geogr. J. 2008, 124, 274–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, V.J.; Cristina, A.; Jiménez, A.; González, D.; Martínez, C.; Cervelló, E. Diferencias según género en el tiempo empleado por adolescentes en actividad sedentaria y actividad física en diferentes segmentos horarios del día. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2017, 31, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Superior de Deportes; Fundacion Alimentum; Fundacion Deporte Joven. Estudio de Los Hábitos de la Población Escolar en España; Consejo Superior de Deportes: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. Encuesta de Hábitos Deportivos 2010; 2833; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas y Consejo Superior de Deportes: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Puerta, L. La Coeducación en España, Un Paseo Por su Recorrido Histórico. In Proceedings of the II Congreso sobre Desigualdad Social, Económica y Educativa en el Siglo XXI, Online, 1–15 November 2017; pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Malavé, P. Análisis de la Brecha de Género en las Clases de Educación Física. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro, S.; Azurmendi, A.; Leunda, G. Guía Para Incorporar la Igualdad en la Gestión de las Federaciones Deportivas; Consejo Superior de Deportes: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, F.; Hernández, A. Intervención para la reducción de la discriminación por sexo en las clases de educación física según los contenidos y agrupamientos utilizados. Rev. Española Educ. Física Deportes 2014, 404, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Blández, J.; Fernández, E.; Sierra, M.A. Estereotipos de género, actividad física y escuela: La perspectiva del alumnado. Profr. Rev. Curríc. Form. Profr. 2007, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.N. Mujer y Deporte. Prejuicios y logros. Rev. Transm. Conoc. Educ. Salud 2009, 1, 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro, E.; Bengoechea, M.; Vázquez, B. Hablamos de Deporte; En Femenino y Masculino; Instituto de la Mujer: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz de Greñu, S.; Anguita, R. Estereotipos del profesorado en torno al género ya la orientación sexual. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2017, 20, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Devís, J.; Fuentes, J.; Sparkes, A. ¿Qué permanece oculto del currículum oculto? Las identidades de género y de sexualidad en la educación física. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2005, 39, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra, J.; García-Pérez, R.; Fernández-García, E.; Rebollo, M.A. Brecha de género en Educación Física: Actitudes del profesorado hacia la igualdad/Gender gap in physical education: Teachers` attitudes towards equality. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2014, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, M. De los dispositivos selectivos en la educación: El caso del sexismo. Rev. Sociol. Educ. RASE 2016, 9, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Guil, A.; Cámara, S. Prevención del sexismo en Educación Secundaria, desde el análisis de la Cultura de Género. Faces Eva. Estud. Sobre A Mulher 2016, 35, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ríos, L.; Buela-Casal, G. Standards for the preparation and writing of Psychology review articles. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2009, 2, 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.W.; Brand, R.A.; Dunn, W.; Spindler, K.P. How to write a systematic review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2007, 455, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. Best evidence synthesis: An intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.J.; Baird, J.; Arai, L.; Law, C.; Roberts, H.M. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr-Anderson, D.J.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Schmitz, K.H.; Ward, D.S.; Conway, T.L.; Pratt, C.; Baggett, C.D.; Lytle, L.; Pate, R.R. But I Like PE: Factors Associated with Enjoyment of Physical Education Class in Middle School Girls. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2008, 79, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrín, A.; León, J.M.; Ortega, E.; Garcés, J. Program for the development of attitudes of equality of gender in classes of physical education in schools. Educación XX1 2012, 15, 271–292. [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo-Andrés, Ó.; Campos-Mesa, M.C.; Ries, F. Gender equality in Physical Education from the perspective of Achievement Goal Theory. J. Sport Health Res. 2013, 5, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, L.; Miraflores, E. A gender equality proposal in Physical Education: Adaptations of football rules. Retos 2018, 33, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Granda, J.; Alemany, I.; Aguilar, N. Gender and its Relationship with the Practice of Physical Activity and Sport. Apunts. Educ. Física Deportes 2018, 132, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J.; Etxebeste, J. Igualdad de Género y Análisis de la comunicación motriz en las tareas de la Educación Física. Mov. Rev. Educ. Física UFRGS 2019, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Recio, P.; Cuadrado, I.; Ramos, E. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de detección de sexismo en adolescentes (DSA). Psicothema 2007, 19, 522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, E.; Piedra, J. Efecto de una formación coeducativa sobre las actitudes hacia la igualdad en el futuro profesorado de Educación Primaria. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2010, 5, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patinet-Bienaimé, C.; Cogerino, G. La vigilance des enseignant-e-s d’éducation physique et sportive relative à l’égalité des filles et des garçons: Physical education teachers’ vigilance towards gender equity. Quest. Vives 2011, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Prat-Grau, M.; Flintoff, A. Tomando el pulso a la perspectiva de género: Un estudio de caso en una institución universitaria de formación de profesorado de educación física. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2012, 15, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Piedra, J.; Rodríguez, A.R.; Ries, F.; Ramírez, G. Homophobia, heterosexism and Physical Education: Students’ perceptions. Rev. Curríc. Form. Profr. 2013, 17, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Miñano, M.J.; Girela-Rejón, M.J. Evaluation of a proposal for training in gender in Physical Education among students of Physical Activity and Sport Science Studies. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 12, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortiguela, D.; Hernando, A. El trabajo coeducativo y la igualdad de género desde la formación inicial en Educación Física. Contextos Educ. 2018, 21, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, R.G.; Gill, D.L. Perceptions of homophobia and heterosexism in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2003, 74, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).