Abstract

Countering human trafficking at a statewide level requires a combination of knowledge from lived experience, inter-sector collaborations, and evidence-based tools to measure progress. Since 2010, the nonprofit Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (LCHT) has collected and analyzed the data on how partners and organizations across the state work toward ending human trafficking. LCHT uses Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) to measure and illuminate promising paths toward ending human trafficking. Through CBPR, many collaborative working documents and activities have been created: Colorado Action Plans, Policy Recommendations, a Partnership Toolkit, and Partnership Convenings. This paper provides a single case study analysis of the Colorado Project, from 2013 through 2023, and offers a glimpse into the goals for the Colorado Project 2028. The ideas, strengths, and challenges presented here can guide other local efforts to support data-informed responses to trafficking. The CBPR methodology sheds light on the changes in Colorado’s anti-trafficking movement and the actions taken on behalf of partnerships (task forces and coalitions) across the state of Colorado. This paper offers a roadmap for collaborative design and decision-making among academic, nonprofit, and public sector partners seeking to conduct research on social movements utilizing a community-engaged process.

Introduction

Reducing human trafficking requires partnerships between government and nongovernment organizations to bring together diverse experiences, perspectives, skills, and knowledge [1]. To best amplify the messages of how to end human trafficking, and to leverage resources, more can be achieved together than one entity or sector alone [1]. Anti-trafficking coalitions are key in coordinating effective institutional, systemic, and governmental response [2]. While coalitions stem from a myriad of backgrounds, including criminal justice, religious sectors, state and federal institutions, human rights organizations, non-profits, and feminist organizations, partnerships between coalitions have successfully coordinated the state and federal-level efforts to reduce human trafficking [2].

However, collaboration requires an investment of time and energy to realize the co-created goals [3,4]. Sustaining collaborations can also prove to be elusive, as funding, leadership, and system priorities may shift [3,4]. Nevertheless, efforts to facilitate collaborative partnerships between coalitions are increasing [5]. The possible dissonance in the core values between coalitions can add complexity to maintaining inter-coalition partnerships. For instance, the nature of each coalition’s organizational structure may differ in terms of hierarchical power, employment status, or resources [3]. This dissimilarity can foster discord during the linkage of coalitions, and effective communication may be threatened without the creation of structures to facilitate multi-coalition partnerships [3].

This paper offers a developmental case study, designed to guide readers through the development of the Colorado Project, the aims and scope of the research design, the data collection mechanisms, and, finally, provide commentary on the opportunities and challenges for communities to consider when utilizing community-based knowledge development and sharing techniques. Through sharing our efforts in this descriptive case study format, the authors seek to spark research efforts beyond the measures of incidence and prevalence. Instead, the Colorado Project may be viewed as an example of how to coach, support, and develop capacity, in concert with practitioners and survivors, around the metrics and techniques that capture how trafficking occurs in different communities and settings (contextualizing experiences of trafficking), while also sharing and disseminating tools for action that communities are currently piloting to address local forms of trafficking. The very explicit goal of this publication is to invite readers to join us as colleagues in collecting data, alongside our community partners, who are diligently serving in efforts aimed at increasing prevention, addressing root causes, supporting survivors, and engaging with law enforcement and the legal system to end human trafficking1.

Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking as Nonprofit Research Partner

The Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (LCHT) is a Denver-based nonprofit whose mission is to inform social change to eliminate human exploitation. As a member of the larger Colorado anti-trafficking response, LCHT conducts research in close collaboration with community, academic, nonprofit, and public sector partners. The mix of multi-disciplinary sectors and perspectives necessary to effect social change are reflected in the name of the organization, the “lab”, as a community space designed to catalyze more effective responses to curb human trafficking. The organization seeks to inform social change by providing data-driven insights that have the power to support decision-making with evidence, reduce uncertainty, enhance the collective capacity to collaborate, and build upon the strength and resilience of communities. By building bridges to conversation and learning, these data-driven insights can provide guidance for community and systemic action to consider changes they can be made from within. Guided by its human rights, social justice, and survivor-centered values, the organization strives for the authentic inclusion and representation of diverse community voices and identities, toward its overall goal to increase an equitable, comprehensive response to human trafficking in Colorado.

LCHT’s positioning as a nonprofit organization that conducts research is particularly noteworthy because LCHT is part of the community responding to human trafficking (not an external research observer). As a nonprofit that exists to pursue a mission, rather than part of a federal, state, or local government system mandate, LCHT has access to different communities that tend to work with or on the periphery of government systems. More specifically, LCHT co-operates the statewide reporting and service provision hotline, conducts training for first responders and a range of professional sectors, manages a leadership development program, and hosts stakeholder convenings to increase their capacity and share promising practices. This positionality presents both opportunities and challenges—LCHT is generally able to convene partners who are unreachable or unwilling to participate with unknown entities, as well as gather deeply nuanced data, but the engagement also requires intensive sensitivity to who the respondents are and what role they play in the Colorado movement.

The Colorado Project as Illustrative Process Case Study

This case study highlights an example of a collaborative research project, LCHT’s Colorado Project to Comprehensively Combat Human Trafficking (the Colorado Project). Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodologies, the execution of the Colorado Project is itself a process of consensus building to empower survivors, professionals, and activists with knowledge, resources, and empathy in order to sustain and increase the efforts to end human trafficking. By presenting this piece as an in-depth case study on utilizing CBPR to guide decision-making in the statewide efforts to support work against trafficking, we are able to demonstrate the promise of catalyzing interventions from a community-driven perspective. As George and Bennett (2005) [6] argue, case studies are effective in illuminating hypothesis formation toward theory development, and in this case specifically, we move toward proposing an alternative, collaborative hypothesis for how to end human trafficking. As a developmental case analysis of a multi-prong initiative to end human trafficking across the state of Colorado, this article provides a set of methodologies designed to ensure the inclusion of community voices beyond most of the “traditional” methodologies seen most often in the literature [7,8]. The use of case study approaches is established across disciplines [9,10,11,12] and affords the opportunity to answer the questions of how anti-trafficking efforts can proceed across a geographically diverse state [13]. The Colorado Projects call attention to important and challenging community response problems, allowing survivors and practitioners to share their experiences, ideas, and data concerning community responses to human trafficking. In the broader field, early anti-trafficking case studies have focused primarily upon the lived experiences of individual survivors, legal cases, and intervention methods; most with very small sample sizes [7,8]. With this statewide case study, we can track the changes in the field over three distinct timepoints and illustrate the development of a statewide-level approach to curb human trafficking.

LCHT intentionally seeks diverse research participation among academics, survivors, activists, community service providers, law enforcement, and marginalized communities. These stakeholders collectively contribute rich knowledge that directly informs a more robust response to human trafficking in the state. LCHT values the contributions of all the authors over these many iterations of the Colorado Project. In order to provide context and give voice to that labor, this paper does not adopt the formal academic process of direct in-text and end of statement citations related to the Colorado Project; instead, in order to best serve the philosophy and complexity of the CBPR work, Appendix A outlines the contributions of most of the authors and co-creators of the knowledge2 in this work. LCHT suggests organizational citations for each iteration of the project, as detailed in Appendix A.

In service of the broader Colorado anti-trafficking movement, the Colorado Project endeavors to address human trafficking by: (1) Providing support for evidence-based practices and decision-making; (2) Enhancing the capacity to collaborate in order to reduce incidences and prevalence; and (3) Reducing uncertainty and conflict. The following sections detail the key decisions and lessons learned across multiple iterations of the Colorado Project; specifically, the paper highlights the choices related to the research design, method selections, participant and respondent recruitment, dissemination and action plan building, as well as ideas for the future.

Aims and Scopes of the Colorado Project

Colorado Project Research Questions, Methodology, and Methods

The guiding and overarching research question across all iterations of the Colorado Project is: “What would it take to end human trafficking in Colorado?” When the Colorado Project was first designed in 2010, the Colorado anti-trafficking landscape consisted of scattered efforts, with frustrated communities cobbling together resources to serve survivors and combat this human rights abuse. Consequently, survivors fell through system cracks and perpetrators went unpunished.

Methodology: Community-Based Participatory Research

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is a methodology designed to produce knowledge and insight in partnership with community-based organizations and individuals [4,14,15]. In many disciplines, the outcomes of CBPR include evidence-based practices [16], behavioral nudges toward pro-social health programs [17], or opportunities for students to engage with communities to honor various forms of knowledge [18,19,20]. These practices often become funding priorities for philanthropic entities, programmatic adoptions by nonprofit organizations, or central to memorandums of understanding between nonprofit organizations and academic institutions. Community-based participatory research practices have evolved from numerous scientific disciplines [20] and are particularly salient in the anti-human trafficking movement. The use of the CBPR methodology in the context of human trafficking is that personal and lived experience is held as being equal (or arguably, more important) to traditionally academic knowledge. Stoecker (2003) [18] argues that community-based research must include a goal of social change aiming to achieve social justice; LCHT attempts to practice this with each Colorado Project. CBPR focuses researchers to engage in research that moves beyond causal mechanism identification [21]. Thus, utilizing CBPR is a natural fit for nonprofits engaged in human rights protections, seeking justice for ongoing exploitation, and particularly for organizations seeking to provide power and a voice to individuals with lived experience.

Nonprofit organizations are typically familiar with the increasing demands for evidence and rigorous evaluation in order to justify planning, decision-making, funding, and program sustainability. However, many nonprofit organizations fail to understand or make distinctions between evaluation research, needs assessments research, and empirical research. Further, a growing body of evidence supports the accountability demands on nonprofits to demonstrate their worth through logic models, program evaluations, and more replicable forms of measurement [22,23,24,25].

The aim of the Colorado Project, as it was initially conceived, was to overcome the boundedness of knowledge occurring in pockets across the state. The fundamental challenge to mobilizing a movement to measure social change is in decreasing the barriers that enhance knowledge transfer across geographic, sectoral, and provider boundaries. Boundaries to knowledge transfer tend to occur where specialization creates blockades [26]. Knowledge is sometimes localized, embedded, and invested in one particular way in a specific community or sector, and it may not be possible to transfer it to other communities [27]. These pockets are both locationally and professionally bound. For instance, in Colorado, the rural and frontier communities have stronger and more salient resource constraints, while the urban communities focus upon the concerns of the prevalence estimates of trafficking. Professional boundaries result from the specialized practices developed in law enforcement, prosecution, human services, shelters, private sectors (construction, agriculture, tourism, etc.), prevention, and numerous types of other industries that intersect in this movement.

The Colorado Project is a unique example of collaborative design and decision-making among academic, nonprofit, and public sector partners seeking to conduct empirical research on social movements by utilizing a community-engaged process. The nature of the CBPR approach to building community coalitions has included: (1) Respectfully centralizing survivor voices and leadership through a trauma-informed approach; (2) Mindful political engagement of multi-sector participation; and (3) Conducting CBPR by gathering data to support coalition strategies and guide policy recommendations [4]. Community-based research integrates research and action with the following core values: individual and family wellness, a sense of community, respect for human diversity, social justice, citizen participation, collaboration and community strengths, and empirical grounding [20]. Further, the CBPR social justice frameworks enable researchers to identify how systems of power and oppression fuel the trafficking of persons, and how the intersections of multiple identities (e.g., gender, race, class, sexual orientation, etc.) create vulnerability within communities [28]. These guiding principles of the Colorado Project shape the methodology and iterative nature of the work.

At several points during the initial design and revision of the Colorado Project questions and methodology, LCHT’s research team made critical choices, carefully balancing theory and practice throughout the design process. As a guide for nonprofit-led research teams, each section below details the goals, choices, and decisions made during the first three iterations of the Colorado Project. Table 1. details the research questions, methods, and sampling designs for each project; following the table are descriptions and commentary related to the changes adopted in each iteration of the projects.

Table 1.

Illustrative Case Study: The Colorado Projects.

The 2013 Colorado Project

In order to better understand the complex nature of the community response to human trafficking, the first iteration of the Colorado Project 2013 posed the following baseline research questions: (1) What is the nature of Human Trafficking in Colorado? (2) What is being done to address human trafficking in Colorado? (3) How is the work being conducted in the areas of Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, and Partnership (the 4Ps)?

Survey. Participants answered questions about the services available for people who have experienced human trafficking, the ways in which anti-human trafficking efforts are approached by the criminal justice system, the various prevention efforts for human trafficking, and the partnerships that exist in the anti-human trafficking movement3. All of the participants were sent a survey electronically, through their email, in which they received an explanation of the study and an invitation to participate. The participants took only the relevant survey sections appropriate to their sector (e.g., service providers took the protection survey, and prevention educators took the prevention survey).

Focus Groups. Focus group interviews with community participants from mental health services, legal services, immigration lawyers, immigrant rights organizations, advocacy organizations, those working with populations experiencing homelessness and interpersonal violence, and law enforcement agencies complemented the survey data. The Colorado Project 2013 focus group participants were asked to describe the issue of human trafficking, the types of cases within their community, how cases are handled in the community, and the specific factors they believe contribute to human trafficking.

The 2019 Colorado Project

The second iteration, the Colorado Project 2019, included purposive and convenience sampling strategies to identify as many agencies and organizations across Colorado involved in anti-human trafficking efforts as possible. In addition to replicating the two original questions —What is the nature of Human Trafficking in Colorado? and What is being done to address human trafficking in Colorado?—a third sub question in the 2019 iteration asked: How do we work together to comprehensively end Human Trafficking in Colorado? In order to address this additional research question, a third type of protocol was implemented to more effectively interpret the rise of partnerships working against trafficking.

Sample frame selection. Selecting the population of task forces active in Colorado as the sample was driven by the goal to track the changes that had occurred over the last five years as a result of legislation passed, community will, public awareness, rules and regulatory guidelines for state and local agencies, and grants providing support for the issue. However, the researchers recognize that this particular decision point led to a need for a significant number of trained interviewers, staff time, project management resources, and calling in personal requests to have participants attend the focus groups, organizational interviews, or complete the survey. Two important trade-offs should be noted as they relate to this methodology: first, by allowing the local focus group leader to select the participants for the organizational interviews and the convenience sample of the willing organizations, the resulting data may reflect opinions of either the task force leader or organizations more ideologically aligned with LCHT. Second, by selecting the original Colorado Project 2013 communities, places where task forces had not formed, left many types of organizations out of the sample frame. Organizations in communities that lack a task force, rural areas, and places where the original Colorado Project did not reach remain beyond the sample frame. To find organizational participants in communities where there were no task forces or partnerships, the research team contacted the Colorado Project 2013 participants and, through snowball sampling, identified additional participants (oversample communities). When there were not enough participants available to host the focus groups in the oversample communities, we added these participants as organizational interviewees.

Organizational Interviews. The research team added a new protocol to the Colorado Project in 2019 to answer more completely how partners and organizations work comprehensively and collaboratively to end trafficking. The focus group participants may have been reluctant to share their perceptions about their community partners in open forums, so these organizational interviews were intended to capture the interactions, shared goals, conflict, trust, and successes of the partnerships. These interviews also yielded data that distinguished between individual providers or community members completing surveys and organizations that work in the anti-trafficking field. Two degrees of a snowball sample design were utilized so new participants could also recommend other participants.

The Colorado Project 2023

Data collection for the Colorado Project 2023 is currently underway; as in the prior iteration, the team will collect the survey, focus group, and interview data. One significant methodological change will occur in this iteration of the project and the research team will implement a new protocol for the years in between the five year intervals of the Colorado Project. The discussion section will describe the launch of the root causes protocol to complement the Colorado Project instruments.

Survey. While the survey will retain many of the items from the prior iteration of the project, LCHT opted to adopt a networked (directional data) tool for the survey data collection. Respondents will now be able to report directly about other organizations in their community on items related to trust, equity, effectiveness, service provision, and participation in the anti-trafficking movement. This approach should help to provide information of opportunities for deeper collaboration among organizations within the same communities and across the partnerships/state.

As the organization continues to refine our tools and processes for data collection and analysis, the information presented in the case study thus far provides details primarily on the what and how aspects of the project; the following sections provide a commentary and exploration into the why of the research products produced, the audiences, the future of these efforts, and the connections to advancing the collective efforts toward ending trafficking.

Implications and Impact of the Colorado Project

Colorado Project Outputs: Advancing and Sustaining Partnerships

Colorado Reports and Action Plans. The Colorado Project findings allow partners to see how their efforts exist within a larger statewide response to human trafficking. With each iteration of the Colorado Project, various outputs are produced alongside a full project report. Embodying the commitment of turning data into action, interdisciplinary committees of professionals representing each of the 4Ps were assembled to review the data and generate Action Plans.

This multi-sector approach was a departure from other state level plans dedicated to reducing human trafficking. The Colorado Project 2013 Action Plan was the first comprehensive, statewide plan in the country to be driven by data and directly informed by a total of 350 participants from the state of Colorado. The overarching recommendations and activities provided the support and structure for the development of tailored and detailed implementation plans that were community-owned and led. In this way, communities were empowered to organize with intention.

In the Colorado Project 2013, a Policy Recommendations document was created in response to a key finding that Colorado’s human trafficking laws needed strengthening. Ultimately, these policy recommendations supported significant updates to Colorado statutes and helped create a Governor-appointed human trafficking council in 2014. One of the key takeaways from the Colorado Project 2019 was that addressing the root causes of trafficking would help to end human trafficking in Colorado (and beyond). LCHT took steps to investigate the existing literature to learn more about the known inequities and barriers to accessing resources for marginalized populations in Colorado. In 2022, LCHT supported allied communities to advocate for the establishment of an Office of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives and supported legislation to provide recourse for survivors of wage theft in Colorado communities.

The Colorado Project 2019 was built upon the foundational knowledge of what is already working in Colorado, as well as a deeper understanding of where gaps exist. In addition to the report and action plan, the outputs included regional community profiles and academic journal articles. Each output had a narrowly defined audience and sought to communicate the research findings (e.g., results and analyses) in ways intended to lead to direct action. The first output, the Colorado Project 2019 Report [29], supported anti-trafficking practitioners and partnership leaders. The report reflected the state of the movement and defined actionable goals for subsequent years.

In order to validate and honor the ongoing inclusion of community voices, LCHT created three checkpoints for data analysis in the process of developing the Action Plan. In the first review, content reviewers examined representative and compelling quotes for inclusion in the report. The Colorado Project 2019 Advisory Committee completed the second review; the Advisory Committee comprised of fourteen professionals divided into their 4P respective areas to review the data and results from the draft 4P-relevant Action Plan recommendations. The Advisory Committee convened to discuss their recommendations to identify points of tension and/or overlap across the P areas. A team of survivors conducted the third review to answer two questions: Do the recommendations reflect trauma-informed and survivor-centered principles? How might these recommendations be implemented or achieved through a trauma-informed, survivor-centered approach? Their suggestions were incorporated into the final Action Plan, which contained ten recommendations alongside implementation suggestions.

Throughout the Action Plan development process, LCHT gave special consideration to creating trauma-informed and survivor-centered recommendations that honored: (1) the unique purpose, mission, vision, and goals of the diverse Colorado partnerships and the collaborative work across disciplines in all of the 4Ps; (2) the lived experiences of survivors and other groups and communities at risk of violence and/or exploitation; (3) the rich diversity of survivor experiences and their views on justice (e.g., for many, outside the criminal justice system); and (4) the vast and nuanced differences among Colorado communities, inclusive of urban, rural, and frontier designations, and their populations. This is one important way the products of the Colorado Project differ—in the Reports, LCHT follows practices and standards long established and practiced in academic circles, such as evaluating intercoder reliability, sampling design practices noted in the previous section, and hypothesis testing. The Action Plans err on the side of following the lead of community members, survivor leaders, Advisory Committee participants, partnership leaders and our other community-based partners. The findings from the Reports and the raw data collected in each iteration of the Colorado Project are the basis for the Action Plans, but the interpretation of that data occurs by allowing the community to drive and decide the priorities for the movement from that data.

Regional Profiles. As with many geographically expansive states, Colorado has significant differences in population density, socioeconomic profiles, ethnic and racial compositions, and local economies. These regional profiles, grouped by judicial district and county, provide specialized feedback on combating human trafficking in seven regions across the state. The profiles include summaries of the vulnerabilities in each region, including population demographics and physical landscape, which influence root causes, the local agencies trained in human trafficking awareness or response, and recommendations specific to the location. Further, the regional community profiles are focused on inviting new audiences and concerned community members to their local anti-trafficking initiatives. The regional community profiles were disseminated in community forums between May and September 2019.

Beyond One-Way Dissemination: Partnership Toolkit, Trainings and Convenings

After completing the report, action plan, regional profiles, and academic journal articles, LCHT set out to fulfill its commitment to CBPR by not only disseminating the outputs of the research to the participants in the research, but also to provide tools to carry out the outcome recommendations. In 2019, there were ten action plan recommendations and, while LCHT did not have the capacity (or the mandate) to carry out all of them, the organization did see three partnership recommendations and two prevention recommendations that LCHT could steward. The three partnership recommendations were:

- Encourage the intentional and equitable inclusion of underrepresented and/or unrecognized stakeholders in partnerships.

- Create a collaborative document that provides promising practices for Colorado partnerships.

- Cultivate relationships between Colorado partnerships to increase each community’s capacity to end human trafficking.

To address the first and second recommendations, LCHT created a Colorado-specific partnership toolkit. LCHT’s Partnership Toolkit is a set of resources and tools designed to improve the coordination and collaboration between multiple stakeholders involved in the anti-trafficking response in Colorado. The toolkit draws from similar projects undertaken by the Anti-Slavery Partnership Toolkit [30] and the Human Trafficking Task Force e-guide [31].

In order to address both the first and third recommendations, LCHT began to host partnership convenings in 2020. The partnership leadership from the existing anti-trafficking partnerships, as well as the community leaders from regions without formal anti-trafficking partnerships, were invited to contribute and participate in quarterly meetings designed to: (1) Increase trust and information sharing between task forces; (2) Highlight promising practices and shared challenges; (3) Increase capacity with shared partnership tools and resources. These meetings were hosted virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic. In September 2021, one or two leaders from each task force gathered in person with survivors, advocates, tribal representatives, and LCHT researchers and staff for two days to further these goals. In 2022, the meetings focused on highlighting the challenges and innovations of specific partnerships across the state. The intended outcomes for the participants were to: (1) Leave with a bias to action; (2) Share the resources that they can bring back to their coalitions/partnerships; (3) Improve rapport between members. For both the partnership toolkit and the partnership convenings, LCHT incorporated the first partnership recommendation into the programming and resources provided to encourage the intentional inclusion of underrepresented stakeholders, particularly survivors, into partnerships.

The two prevention recommendations that LCHT opted to steward from the 2019 Action Plan were:

- Deliver sector-specific training to a diverse range of Colorado communities.

- Design comprehensive training.

As LCHT already had a robust training and education program, LCHT adjusted the strategy of the program to reflect these recommendations. Training for healthcare professionals, law enforcement, and professionals working with systems-involved youth were prioritized in 2019. New training curricula, to improve the comprehensiveness of LCHT’s educational programs, were developed for young people and individuals experiencing homelessness and/or substance misuse. In 2019, LCHT trained 5355 individuals; in 2020, 5424 individuals; and in 2021, 6096 individuals. In 2022, LCHT will also train over 6000 individuals. LCHT also made their training and technical assistance tools more accessible by offering training in Spanish, or with Spanish interpretation, as well as creating documents in Spanish.

Discussion and Next Steps

Lessons Learned on the Path to Colorado Project 2023

Nonprofit-led CBPR. While the research team held a mutual agreement about the goals for conducting CBPR, three key lessons emerged: (1) The need for patience in building organizational learning; (2) Disrupting the identity role of a nonprofit; and (3) Reaching diverse and new audiences through engaged methodology. Building organizational learning was a key component and outcome of the CBPR model. LCHT grew from the process of the Colorado Project 2019, by allowing LCHT board members and staff opportunities to better understand their roles relative to LCHT and broadening their understanding of what form human trafficking takes in Colorado. The research team members shared reflections on what the organization as a whole learned through the research and recognized the impact of the time and energy spent on the project for the right-size planning of the Colorado Project 2023.

As a nonprofit that conducts research, LCHT finds itself constantly navigating identity. LCHT must simultaneously build credibility across organizations representing all of the 4Ps, with researchers in the academic sector, with survivors who hold multiple lived experiences and perspectives, and with citizens new to understanding how human trafficking occurs in their community; the interdisciplinary nature of the work requires diplomacy and careful trust-building. LCHT attempts to achieve this in a few key ways: (1) Respectful interactions in varied partnerships by attentively listening to stakeholders and being prepared to share, but not take a leading role in communities outside of its home community (Denver Metro Area); (2) Conducting joint trainings; and (3) Intentionally taking time to maintain and cultivate relationships.

The most significant challenge faced when leading research on human rights abuses while participating in the movement is that LCHT argues for metrics and targeted social change while actively being in partnership with the agencies doing work on the ground. However, LCHT does not evaluate the anti-trafficking movement and made this decision intentionally in order to ensure the organization is not perceived as passing judgment on the efforts of partners. For example, managing the statewide hotline put LCHT at the center of a key statewide partnership. This positionality can create friction, such as when the research findings challenge LCHT’s position as an advocate and partner. LCHT must acknowledge that its reputation could be in jeopardy when conducting original CBPR work.

A central goal of the Colorado Projects is to amplify the voices of those involved in the movement and find opportunities to invite in new voices. The aim of reaching many audiences is to invite in additional partners as opposed to calling out problems in the field. Statewide evidence helps to educate those new to anti-trafficking response efforts and helps to educate those who may have blind spots.

The Colorado Project 2023 Innovations

The Colorado Project 2019 Action Plan identified several key areas to address and provided subsequent commentary on the movement itself [4,32]. The current framework of the 4Ps is often restrictive and misleading. For example, funding allocation largely depends on assumptions about the effectiveness of prevention programs. Furthermore, shifting resources to fund prosecution, for example, may not lead to a reduction in crime rates. Instead of aiming for an increased number of convictions, there are other strategies to limit the financial rewards of exploitation that may not fall under the 4Ps framework. However, LCHT acknowledges the limitations placed on the response efforts resulting from the 4P paradigm.

LCHT learned valuable lessons through conducting the Colorado Projects in 2013 and 2019, which support methodological and project management improvements for the third Colorado Project in 2023. In the years since the Colorado Project 2019, tremendous global and social shifts took place: the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing severity of climate change-related disasters, federal administration changes, racial justice protests, restrictions on women’s reproductive health access, global migration in response to social unrest, and conflict. It became clear that additional questions were needed to enhance the basic questions of how to address human trafficking in Colorado.

Based on the feedback from the partners adopting the LCHT Action Plan, three major pillars for the Colorado Project 2023 emerged: Effectiveness, Equity, and Trust. Scholars across disciplines argue that a primary issue for combating human trafficking is that an immense amount of money, effort, and resources go into prevention and protection efforts, while there is scant evidence that such programs are effective [33,34]. Similarly, findings from the early iterations of the Colorado Project suggest that few survivors are leading partnerships to end trafficking and that some anti-trafficking efforts tokenize survivor engagement. Equity appears essential to understanding the effective mechanisms for reducing trafficking. In order to partner across disciplines and fields, trust must be earned and fostered over time. Trust, therefore, is an essential component of ending trafficking through partnership, shared goals, and service delivery. To understand the role of equity and trust as they contribute to effectiveness, the Colorado Project 2023 will implement a social network analysis tool to allow the respondents to reflect on their relationships with key stakeholders and community partners.

Adding Network Analysis

Collaboration has excellent potential to increase access to new information, resources, and solutions. However, collaboration requires an investment of time to communicate and realize the shared mission, vision and goals. In a partnership, it is often difficult to see returns on investment from these critical activities. Social network analysis allows for the examination of partnerships by analyzing the structure, quality, and flow of information across a network, in order to help identify more efficient ways to collaborate and reach the shared goals. The network survey is distributed to each bounded network, and includes a core set of network relationship questions and measures developed and validated by the Program to Analyze, Record, and Track Networks to Enhance Relationships (PARTNER) Tool [35]. Task force members will complete the surveys about other members in their task force. There are currently 21 task forces/coalitions ready to participate across Colorado.

In Spring 2023, LCHT will initiate statewide community conversations to gather key stakeholders and individuals with lived experience in four root cause areas. The investigation of the first four root causes will lay the groundwork to support the efforts aimed at reducing vulnerabilities to experiencing trafficking. Two of these root cause focus groups are intended to determine how immigration and housing insecurity influence vulnerabilities to and perpetration of trafficking. Many community groups fighting trafficking suggest that specific groups of people are more vulnerable to trafficking; in order to explore these claims, two roundtables will be held with Native American/Indigenous and Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer (LGBTQ+) communities. Community conversations across Colorado will identify the risk and resilience factors for human trafficking. Another goal of these conversations is to invite in key stakeholders who may want to create questions and co-design research for the Colorado Project 2028.

Colorado Root Causes: Laying foundation for Colorado Project 2028

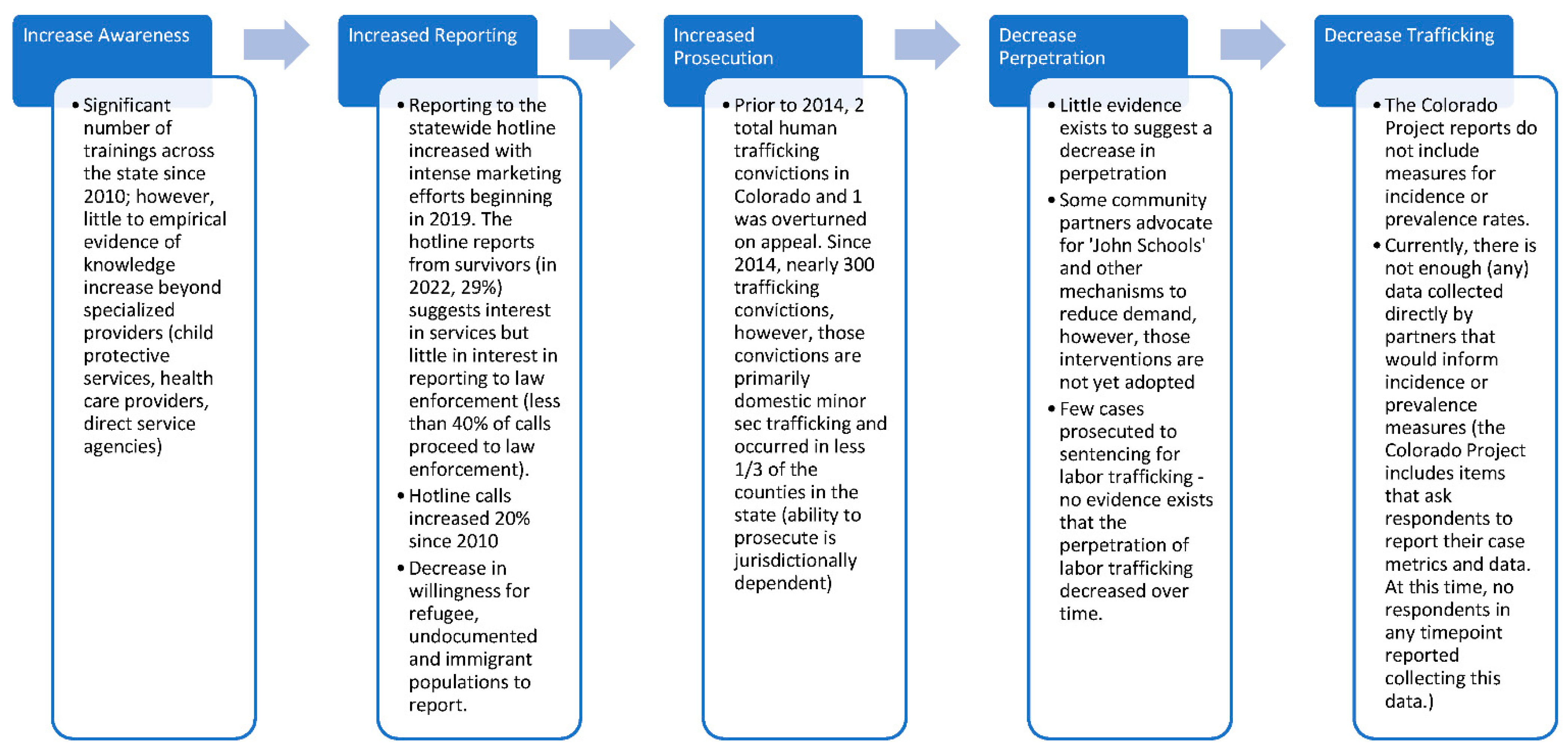

In the early years of the Colorado anti-trafficking response, as has been the case in so many countries and states, the adoption of global and federal 4P language helped to provide shared definitions for response and helped to illustrate the benefits of having comprehensive efforts coordinated at the community level. In the Colorado Project 2028, the LCHT team will attempt to test two competing hypotheses, outlined in Figure 1: Criminal Justice Mechanism, a primarily prosecution mechanism for ending trafficking and Figure 2: Hypothesized Collaboration Mechanism, a root causes through protection (collaborative and comprehensive) mechanism for ending trafficking (see Figure 2). The criminal justice mechanism follows this pathway: Increase awareness of human trafficking as a crime and human rights violation among citizens, law enforcement and prosecutors -> increase reporting of human trafficking to law enforcement -> Increase investigations and prosecutions -> Decrease perpetration of trafficking and exploitation -> Decrease in trafficking. This criminal justice mechanism, currently the underlying assumption for how to end trafficking in many communities, does not seem to be working. For example, prior to 2014, there were only two trafficking convictions in Colorado, and one of these was overturned. Since 2014, the majority of convictions are domestic minor sex trafficking (DMST), largely due to increased mandatory trainings of child welfare workers. With the political and social changes in recent years, there is a decrease in the willingness of refugees, as well as undocumented and documented immigrants, to report abuse and exploitation [36,37]. Additionally, the length of time from discovery to prosecution is, on average, two to four years [38].

Figure 1.

Criminal Justice Mechanism.

Figure 2.

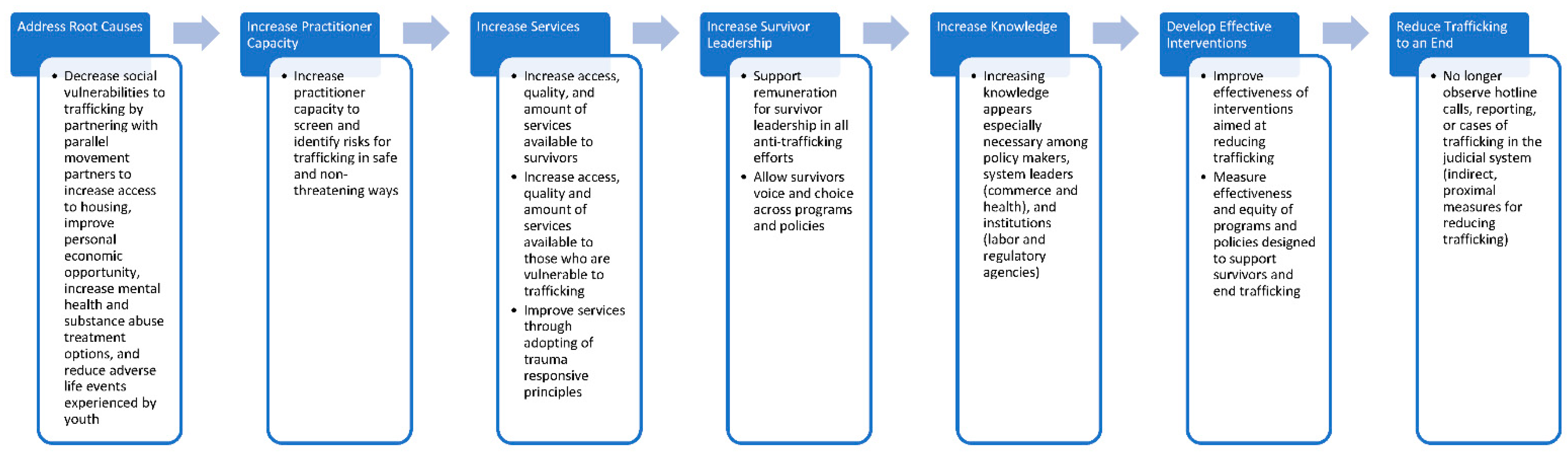

Hypothesized Collaborative Mechanism.

An alternative explanation for how trafficking ends is the root causes and collaboration comprehensive mechanism. This mechanism may follow this path: Decrease social vulnerabilities to trafficking by partnering with parallel movement partners to increase access to housing, improve personal economic opportunity, increase mental health and substance abuse treatment options, and reduce adverse life events experienced by youth -> decrease the root causes of trafficking -> increase practitioner capacity to screen and identify risks for trafficking in safe and non-threatening ways -> increase in services for survivors that address the specific needs of each individual -> increase survivor leadership and self-determination -> increase systemic and policy maker awareness of the impact of reducing root causes and vulnerabilities -> reduce trafficking prevalence while creating a positive feedback loop to continue decreasing vulnerabilities. In the first two Colorado Projects, LCHT identified key community factors that increase vulnerabilities to human trafficking. Political, economic and social factors, such as access to education, healthcare, affordable housing, work, and social protections for gender, culture, race, legal status, and minoritized identities [32,39], appear to be factors that contribute to experiencing trafficking. In order to test these mechanisms, new data sets and additional methods will be part of the Colorado Project 2028.

Sustaining the Colorado Statewide Movement: Ongoing Partnership Engagements

Ideally, the anti-trafficking movement will move beyond the need for basic human trafficking training for professional audiences by 2023. However, in Colorado, hundreds of thousands of professionals still do not understand the scope of the issue, how it affects their communities locally, or how their profession can play a role in prevention, protection, or prosecution efforts. In 2023, LCHT will create a new strategic plan to address this gap for both professional audiences and audiences including marginalized groups who may be vulnerable to exploitation based on the outputs of the Colorado Project. For the 2023 iteration of the Colorado Project, LCHT will collect prosecution data, supplementing those data with interviews from prosecutors to better understand the prosecution outcomes and make recommendations to improve those outcomes while adding to the knowledge base for the Colorado Project 2028.

LCHT learned from the Colorado Project 2019 that incorporating human trafficking into the purview of existing partnerships, particularly multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs), was an emerging promising practice in Colorado. Establishing regional and statewide MDTs to support survivors of human trafficking is key to their resilience [40]. In Colorado, the Governor’s Human Trafficking Council secured federal funding to support MDTs. LCHT looks forward to hearing more about these emerging recommendations.

Conclusions

After more than a decade of designing, collecting data, and working toward filling gaps, each iteration of the Colorado Project adds to the knowledge base. Anecdotally, partnership members are using the information in a variety of ways: facilitating partnership meetings with a more inclusive representation of sectors, incorporating the data into funding applications, building on the questions to explore prosecution challenges more in-depth, organizing convenings of partnership leaders across the state to learn from and support each other.

In order to support researchers within the anti-trafficking field and across the parallel movements, this paper guides non-profit led researchers in utilizing CBPR, developing longitudinal protocols, and enhancing collaborative efforts to comprehensively end human trafficking. While there are many different outputs produced from the Colorado Project findings and recommendations, the Colorado Project process serves as a means for consensus building to empower survivors, professionals, and activists with knowledge, resources, and empathy. Stakeholders can collectively celebrate the strengths and see the challenges in the statewide response, ideally working to break down siloed efforts, and instead partnering to be more efficient and effective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., K.N., A.A.-S., J.L. and A.F.; methodology, A.M., A.A.-S., K.N. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-S. and A.M.; writing this version, A.M., A.A.-S., J.L., N.C., N.G.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-S. and A.M.; supervision, A.A.-S.; project administration, A.A.-S., A.F., K.N., N.G., N.C., A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding; however, this research is led by a nonprofit organization that receives multiple and various sources of funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Colorado Project 2.0. (6 April 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

As noted in footnotes, this data is not publicly available as LCHT holds intellectual property copyright. However, if you would like to utilize the data, please contact the Research Director for LCHT.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Alexandra Brodsky and Savannah Anderson, Leadership Development program participants at LCHT.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

LCHT Recommended Colorado Project Citations:

Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (2019). Colorado Project to Comprehensively Combat Human Trafficking 2.0 and Colorado Action Plan 2.0. Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking. Denver, CO, USA.

Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (2013). Colorado Project Statewide Data Report. Denver, CO, USA: Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking.

Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (2013). Colorado Project National Survey Report. Denver, CO, USA: Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking.

Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (2013). Colorado Project Executive Summary. Denver, CO, USA: Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking.

CBPR Authorship Criteria: Design and Writing

Colorado Project 2013: Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (2013). Report Produced By: Alejano-Steele, Finger, Breslin, and Shaw (15 additional on Project Team).

Colorado Project 2019: Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking (2019). Report Produced By: Miller, Alejano-Steele, Finger, Napolitano, and Tull (33 additional contributors).

Regional Profiles 2019: Miller and Napolitano.

Action Plans 2013 and 2019: Colorado Project Advisories.

Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking Staff and Board.

Colorado Project Action Plan 2013: Brian Abbrecht; Thomas Acker, Ph.D., M.A.; Flora Archuleta; Kathleen Brendza, M.N.P.M.; Sheana Bull, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Anne Darr, M.A.; Janet Drake, Esq.; Betty Edwards, M.B.A.; Gayle Embrey, M.A., LPC, CACII; Brad Hopkins, Th.M.; Magalie Lerman; Annaken Mendoza-Toews, M.S.W.; Cynthia Newkirk-Noah; Barbara Paradiso, M.P.A.; Jen le Roux, Ed.M.; and Jack Wylie.

Colorado Project Action Plan 2019: Eight survivor leaders; Kelsey Antun; Paula Bragg; Lori Darnel, J.D., MSW; Claude d’Estree, HTS, J.D.; Janet Drake, Esq.; Melanie Gilbert, Esq.; Andrew Kline, Esq.; Elizabeth Ludwin King, Esq.; Debbie Manzanares; Patricia Medige, Esq.; Sara Nadelman; David Shaw, MA; Jennifer Stucka; Maria Trujillo, MA.

Notes

| 1 | While the Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking protects their intellectual property investments by not openly publishing instruments utilized in collecting the Colorado Project data, we welcome the opportunity to connect with you if you would like additional details about the contents of those instruments. |

| 2 | Some participants and all of the respondents were granted confidentiality and/or anonymity. |

| 3 | Please note that LCHT views their anti-trafficking work as part of social movement. There are many conversations across anti-trafficking coalitions and partners who suggest that this work does not constitute a social movement. |

References

- U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Person Report; U.S. Department of State: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Trudeau, E.H. The Anatomy of a Social Justice Field: The Growth, Collaboration, and Dissonance of the Modern US Anti-Trafficking Movement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Foot, K. Multisector Collaboration against Human Trafficking. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Human Trafficking; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 659–672. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.; Alejano-Steele, A.R.; Finger, A.; Napolitano, K. The Colorado Project to Comprehensively Combat Human Trafficking: Community-Based Participatory Research in Action. J. Hum. Traffick. 2022, 8, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preble, K.M.; Nichols, A.; Owens, M. Assets and Logic: Proposing an evidenced-based strategic partnership model for anti-trafficking response. J. Hum. Traffick. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LCHT Regional Profiles 2019. Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking, Denver CO, USA. Available online: https://combathumantrafficking.org/our-research/colorado_project_2.0/ (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Bump, M.N.; Gozdziak, E.M. Data and Research on Human Trafficking: Bibliography of Research-Based Literature; Final Report Prepared for Karen J. Bachar; Division Office of Research and Evaluation, National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice NIJ: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Russell, A. Human trafficking: A research synthesis on human-trafficking literature in academic journals from 2000–2014. J. Hum. Traffick. 2018, 4, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure. Qual. Inq. 2011, 17, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, M.D. Qualitative Research in Business & Management; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hyett, N.; Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V. Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 23606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.D. Interpretive research aiming at theory building: Adopting and adapting the case study design. Qual. Rep. 2009, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Corus, C.; Fisk, R.P.; Gallan, A.S.; Giraldo, M.; Mende, M.; Mulder, M.; Rayburn, S.W.; Rosenbaum, M.S.; et al. Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikesell, L.; Bromley, E.; Khodyakov, D. Ethical Community-Engaged Research: A Literature Review. Am. J. Public Heal. 2013, 103, e7–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100 (Suppl. 1), S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoecker, R. Community-based research: From practice to theory and back again. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2003, 9, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Strand, K.J.; Cutforth, N.; Stoecker, R.; Marullo, S.; Donohue, P. Community-Based Research and Higher Education: Principles and Practices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S. Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educ. Action Res. 2006, 14, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H. Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for Organizational and Social Research; Oxford University Press on Demand: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides, E.; del Amo, M.C.A.; Romero, C.L. Profiles of social networking sites users in the Netherlands. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual High Technology Small Firms Conference, HTSF 2010-University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 27–28 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, A. Accountability myopia: Losing sight of organizational learning. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2005, 34, 56–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. The relationship of nonprofits’ financial health to program outcomes: Empirical evidence from nonprofit arts organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 46, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch-Cerullo, K.; Cooney, K. Moving from outputs to outcomes: A review of the evolution of performance measurement in the human service nonprofit sector. Adm. Soc. Work. 2011, 35, 364–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, P.R. A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J.; Elias, M.; Wandersman, A. Citizen participation and empowerment. In Community Psychology. Linking Individuals and Communities; International Student Edition; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 398–431. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C.N. Moving beyond “Slaves, Sinners, and Saviors”: An Intersectional Feminist Analysis of US Sex-Trafficking Discourses, Law and Policy; Faculty Publications, Smith College: Northampton, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- LCHT, The Colorado Project 2019 Report. 2022. Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking, Denver CO, USA. Available online: https://combathumantrafficking.org/our-research/colorado_project_2.0/ (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- University of Nottingham Rights Lab. Anti-Slavery Partnership Toolkit; University of Nottingham Rights Lab: Nottingham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Office for Victims of Crime, Training and Technical Assistance Center. Human Trafficking Task Force e-Guide; Office of Justice Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, P. Barking up the Wrong Ps: How the Current 3P Framework is Hindering Anti-Trafficking Efforts and What We Might Do Instead; Research and Communications Group: Wellington, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, K.; Landman, T. Combatting human trafficking since Palermo: What do we know about what works? J. Hum. Traffick. 2020, 6, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, D. Anti–human trafficking interventions: How do we know if they are working? Am. J. Eval. 2016, 37, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varda, D.M.; Sprong, S. Evaluating networks using PARTNER: A social network data tracking and learning tool. New Dir. Eval. 2020, 2020, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, R.; Kilborn, M.; Woldemikael, O. Immigration policies and access to the justice system: The effect of enforcement escalations on undocumented immigrants and their communities. Political Behav. 2022, 44, 1359–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbash, L.A.; Ronis, S.T. Making a dent in human trafficking: Investigating the effects of social institutions and policies across 60 countries. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2021, 76, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, C.S. Human Trafficking Cases Reported/Prosecuted within 22 Judicial Districts, 2015–2022 § 18-3-503 C.R.S., § 18-3-504 C.R.S., and § 18-3-504 (2) C.R.S.; Division of Court Services, State of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Musto, J.; Thakor, M.; Gerasimov, B. Between Hope and Hype: Critical evaluations of technology’s role in anti-trafficking. Anti-Traffick. Rev. 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromknecht, A. Grants to Address Trafficking within the Child Welfare Population; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).