Barriers to Educational Inclusion in Initial Teacher Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Are there barriers in initial teacher training when it comes to acquiring skills for inclusive education?

- -

- Have teachers received professional or practical preparation in their training to meet the diversity of student needs?

- -

- What training approach prevails in teacher training regarding attention to diversity?

2. Methods

2.1. Design

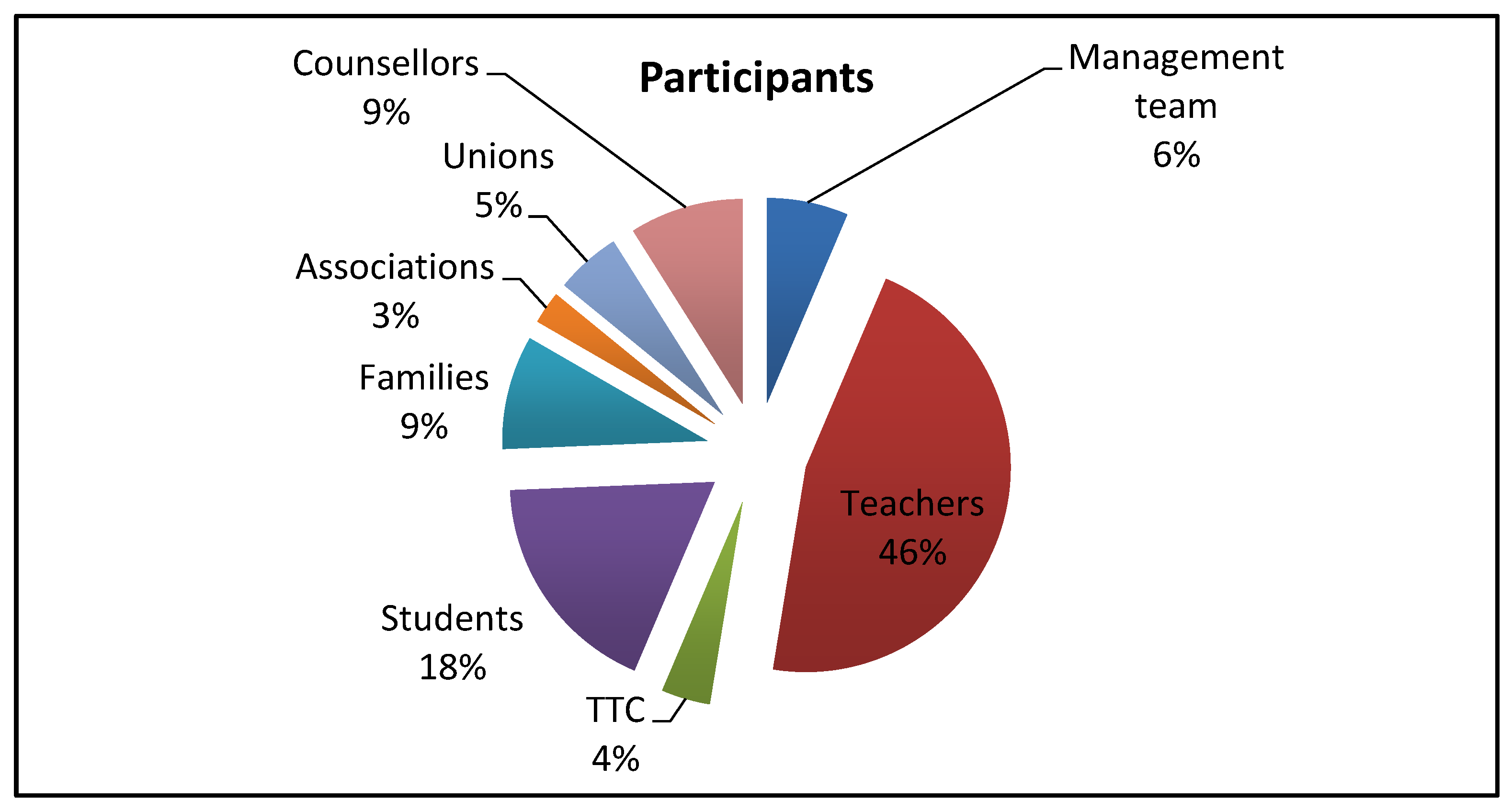

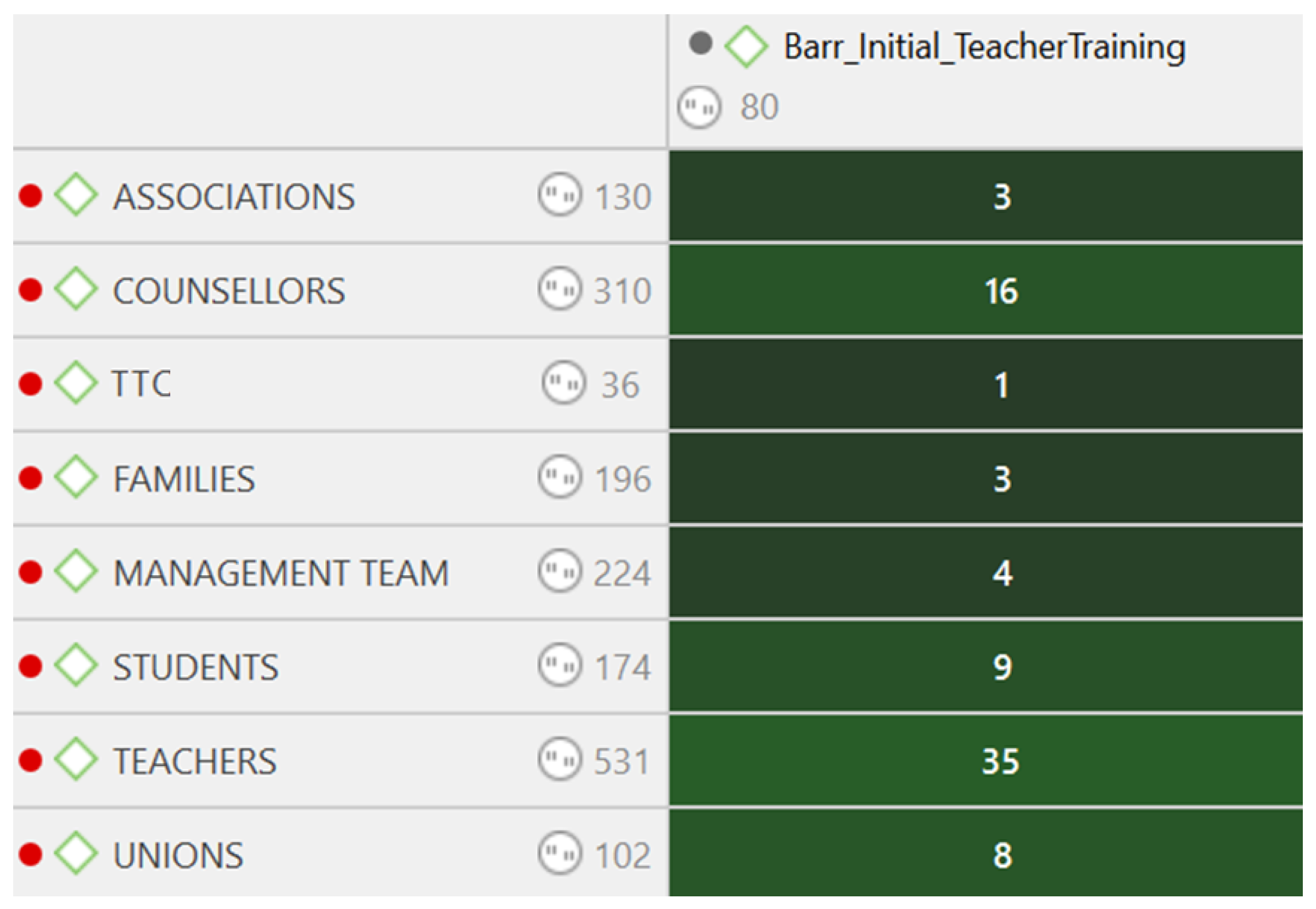

2.2. Participants

2.3. Information Gathering Techniques

- -

- Semi-structured interviews: A total of 39 semi-structured interviews were carried out. These were carried out by researchers from the group “Inclusive Education: A School for All” (EDUIN) with: 5 centre directors; 7 educational counsellors; 1 teacher; 3 family members; 10 students; 6 political representatives, 5 trade union representatives and 2 association representatives. Some of the interview questions were: Are there barriers in initial teacher training to inclusive education? Do the university training centres offer teachers the necessary skills and abilities to attend to diversity? Are the teachers aware of the educational legislation for attention to diversity? What formative approach is used in universities in relation to inclusive education? What role should the educational administration assume in the promotion of inclusive education in teacher training?

- -

- Focus groups: A total of 10 focus groups were conducted, 7 of them with teachers, 1 with families, 1 with students with disabilities and 1 with professionals from the Teacher Training Centre (TTC). To carry out the focus groups, a guide was designed in which information was collected regarding: 1) instructions and contextualization of the study; 2) socio-demographic data of the participants; and 3) topics of interest on teacher training in the Region of Murcia regarding attention to diversity (initial training and ongoing training).

2.4. Process

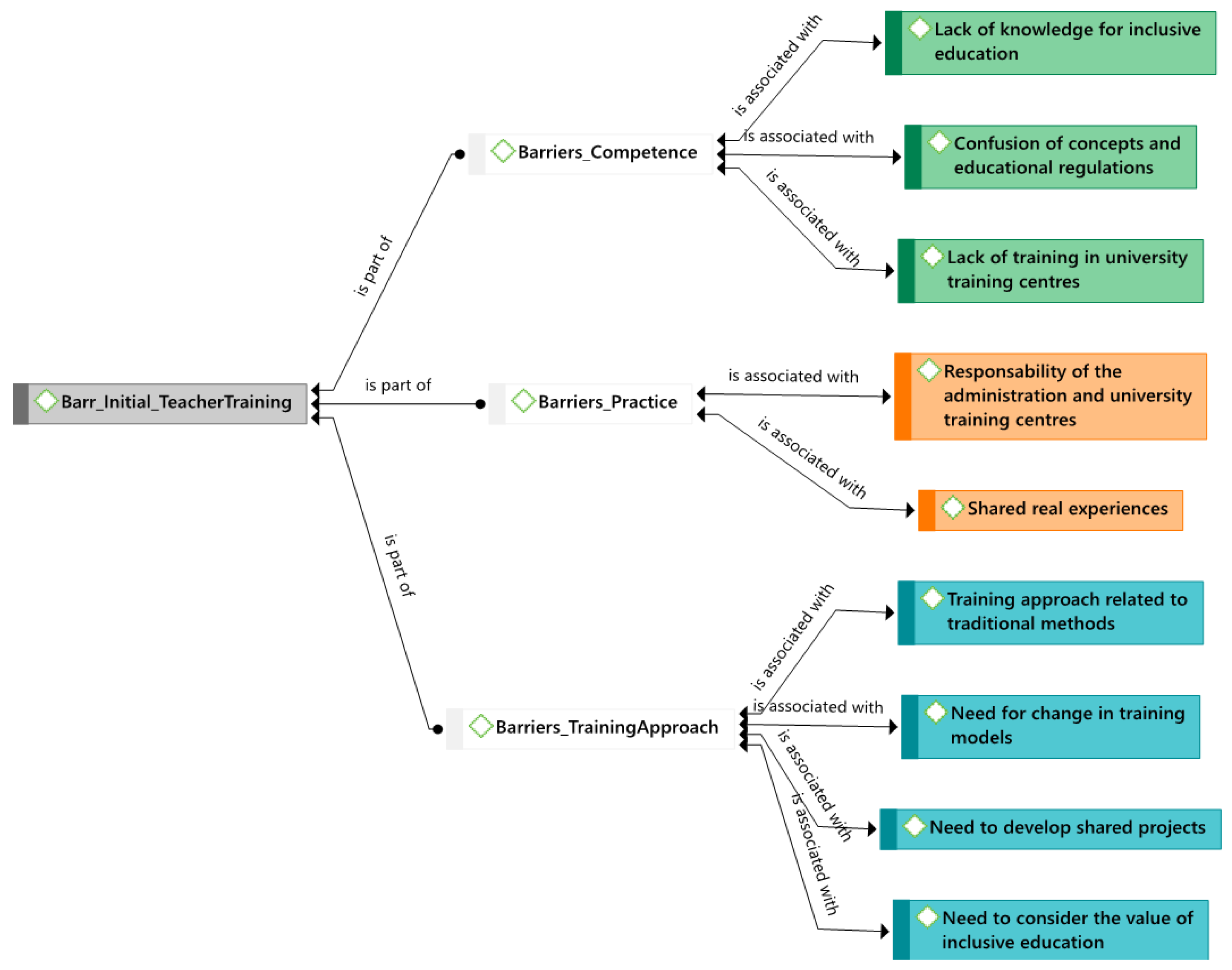

2.5. Analysis of the Information

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Are There Barriers in Initial Teacher Training Regarding the Acquisition of Skills for Inclusive Education?

I would add that there are very few hours of education dedicated to inclusion in university studies. I do not know about you, but I did not do any (Secondary_Teacher).

Graduates fresh out of university do not know how to distinguish between a Student with Specific Educational Support Needs (ACNEAE) and a Student with Special Educational Needs (ACNEE). They do not know what he decrees re diversity is, they have no idea what measures should be applied... They are absolutely stuck on something as fundamental as that. Additionally, I find myself repeating the same thing again and again, forty years ago when I was at university, it was considered normal, but today? (Primary_Teacher).

There is a need for better training at the University level. They leave university unclear about many things, even in the area of specialization, special education. That is essential (Families_Secondary).

Additionally, if it is already a problem in infant and primary education, which is already an obstacle, it also happens with secondary school and sixth form teachers [...] These people have studied a degree in mathematics, physics, chemistry, where there has been no subject related to the world of education, neither didactics nor organization; absolutely nothing. […] Their academic curriculum should be changed, and whoever wants to be a teacher should take some electives that will direct them towards the world of education (Management team_Primary).

In my opinion, there is a lack of training on the part of future teachers regarding inclusive education, starting with their principal degree subject and continuing through to the Master’s Degree in Teacher Training (in which inclusion is given only superficial attention) (University Students).

3.2. Have Teachers Received Professional or Practical Training in their Training to Meet the Diversity of Student Needs?

There is a very large gap between the university and the real life of educational centres. One thing is theory and another thing is day-to -day practice (Primary_Teachers).

I left teacher training without knowing how to teach a child to read, and when I finished my third year I said: “Okay, now I am going to a classroom and I do not know how to teach a child to read” (Counsellors).

In university degrees, only very general training is given on attention to diversity. This does not correspond to the real difficulties that exist in schools and classrooms (Unions).

With the changes, in the new methodological criteria that they want to implement, the first problem arises, which is the initial training of teachers, since there should be a much greater connection between what is learnt at university and what is actually applied in the classroom (Management Team_Primary).

In my case, the theory given at the university has not served me as much as I imagined. Let me explain: despite the fact that the contents acquired are real and useful, it is not until you face reality in an education centre (in 4th grade) that you really understand everything that was only previously explained on paper (University Students).

3.3. What Training Approach Prevails in Teacher Training Regarding Attention to Diversity?

We would have to start by offering different training to all teachers (Management Teams_Primary).

I sincerely believe that most teachers were not well prepared to care for me. The only ones who have known how to teach me well have been the teachers of Therapeutic Pedagogy and Hearing and Language Support in the open classrooms (Student_Secondary).

For example, many teachers do not know how to teach a child with autism because they have not studied subjects that teach them how to respond to the needs of this type of student. There should be subjects or courses on attention to diversity for all teachers in university training -and not only for teachers who study the specialist degree in Therapeutic Pedagogy—(Associations).

That curriculum should be changed and whoever wants to be a teacher should take some electives that would direct them towards the world of education. Additionally, you no longer need a master’s degree, since within your academic curriculum you study an education module. However, well, that a physicist who is extremely intelligent gets into a classroom of the first or second stage of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO)... Let us see what he does with thirty-five students of that kind (Management Team_Primary).

The theory fails us when other teachers later tell us, very vehemently: “It’s because that boy in the class is not going to learn, there’s no way, I cannot do anything for him...” Well, you believe it, you believe it because you lack the spark to say: no, there has to be another way of doing it (Teacher_Primary).

We are clear that the initial teacher training would have to undertake an important change of direction. However, well I think it has to come from above. […] We are in a country where I believe that education does not matter to anyone. What matters in education? The commercialization of education. Additionally, I say it again, it does not matter to anyone, because if it mattered things would have changed (Teacher_Secondary).

It is very important to promote innovative projects and the development of collaborative learning communities between teachers (Teacher Training Centre).

4. Conclusions and Implications for Education

- -

- The existence of training barriers in the initial training of teachers in centres of higher education means that students do not acquire the necessary skills to develop an equitable and quality education for all. In this way, graduates do not have the skills, abilities, knowledge and attitudes necessary to practice the teaching profession from an inclusive approach. This constitutes an important barrier to inclusion.

- -

- The presence of barriers is linked to training models based on theory and without a connection to education practice. This undoubtedly, hinders future teachers by failing to make the connection between theory and practical intervention, and thereby lacking an inclusive pedagogy in their repertoire of skills. The educational administration occupies an essential role in this regard, which it is carrying out inadequately in facing up to the current challenges.

- -

- There is a need to rethink the existing teacher training model. When faced with the current challenges, all teachers, both general and specialist, should receive training that enables them to meet the objectives set out in the inclusion paradigm. This requires the abandonment of training models anchored in the deficit model that has characterized education practices for attention to diversity for a long time. Consequently, future research should consider inclusion as an essential value in training plans, as this is the essential principle for an efficient and quality school for all.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Units Nations. Guía para Asegurar la Inclusión y la Equidad en la Educación; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259592 (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Kyriakides, L.; Charalambous, E.; Creemers, P.M.; Dimosthenous, A. Improving quality and equity in schools in socially disadvantaged areas. Educ. Res. 2019, 61, 274–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, D.C.; Cunning, D. Making explicit pre-service teachers’ implicit beliefs about inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 1494–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, R.H. El maestro en la Unión Europea: La Europa de las competencias. Tend. Pedag. 2009, 14, 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Berikkhanova, G.; Ospanova, B.; Yermenova, B.; Zharmukhametova, R.; Sultanova, N.; Urazbaeva, A. The effectiveness of the training model of the future teacher in conditions of inclusive education. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2021, 9, 670–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Educating teachers for the future school- the challenge of bridging between perceptions of quality teaching and policy decisions: Reflections from Norway. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 44, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Units Nations. Declaración de Incheon. In Educación 2030: Hacia una Educación Inclusive, Equitativa y de Calidad y Aprendizaje a lo Largo de la Vida Para Todos; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gavish, B. Four profiles of inclusive supportive teachers: Perceptions of their status and role in implementing inclusion of students with special needs in general classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 61, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz-Sánchez, P. La educación inclusiva: Mejora Escolar y Retos para el Siglo XXI. Part. Educ. 2019, 6, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitoller, F.R.; Thorius, K.A.K. Sustaining Disabled Youth: Centering Disability in Asset Pedagogies (Multicultural Education Series); Teachers College Press: Columbia, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T.; Ainscow, M. Index for Inclusion: Developing and Participation in Schools, 2nd ed.; Centre for Studies in Inclusive Education (CSIE): Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Echeita, G. Educación para la Inclusión o Educación sin Exclusiones; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Victoriano, E. Facilitadores y barreras del proceso de inclusión en educación superior: La percepción de los tutores del programa Piane-UC. Estud. Pedagóg. 2017, 43, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gil, F.; Martín-Pastor, E.; Poy Castro, R. Educación inclusiva: Barreras y facilitadores para su desarrollo. Análisis de la percepción del profesorado. Profesorado. Rev. Curríc. Form. Profr. 2019, 23, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccio, L. Head Start Instructional Professionals’ Perceptions and Practices: Facilitators and Barriers for Including Young Children with Disabilities. Ph.D. Thesis, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moriña, A. Approaches to Inclusive Pedagogy. A Systematic Literature Review. Pedagogika 2020, 140, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakolade, O.; Adeniyi, S.; Tella, A. Attitude of teachers towards the inclusion of special needs children in general education classrooms: The case of teachers in some selected schools in Nigeria. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2009, 1, 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaiz-Sánchez, P.; Escarbajal-Frutos, A.; Alcaraz-Garcia, S.; de Haro-Rodriguez, R. Teacher Training for the Construction of Classrooms Open to Inclusion. Rev. Educ. 2021, 393, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. What counts as evidence of inclusive education? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, I.; Moriña, A. How to become an inclusive teacher? Advice for Spanish educators involved in early childhood, primary, secondary and higher education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.A.; Muñoz, I.M.; Beas, M. Modelos de formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Secundaria en España desde una perspectiva Europea. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2014, 26, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, R. Identidad Profesional, Necesidades Formativas y Desarrollo de Competencias Docentes en la Formación Inicial del Profesorado de Secundaria. 2013. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/bitstream/handle/10396/11450/2013000000857.pdf?sequence=3 (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- EURYDICE. Cifras Clave del Profesorado y la Dirección de Centros Educativos en Europa; Secretaría General Técnica. Centro de Publicaciones. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/cifras-clave-del-profesorado-y-la-direccion-de-centros-educativos-en-europa-edicion-2013/ensenanza-profesores-union-europea/16288 (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- EURYDICE. La Profesión Docente en Europa. Prácticas, Percepciones y Políticas; Secretaría General Técnica. Centro de Publicaciones. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: www.cerm.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Laprofesiondocenteeneuropa_1.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Units Nations. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education; UN: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248254 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Fernández, C.; Fiouza, M.J.; Zabalza, M.A. A propósito de cómo analizar las barreras a la inclusión desde la comunidad educativa. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2013, 11, 172–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, H.J. La Formación inicial del profesorado para la inclusión. Un urgente desafío que es necesario atender. Publicaciones 2019, 49, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C. Developing and implementing quality inclusive education in Hong Kong: Implications for teacher education. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2010, 10, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for the Development of Education for Pupils with Special Educational Needs. Teacher Education for Inclusion across Europe. Challenges and Opportunities; European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education: Odense, Denmark, 2011; Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/teacher-education-inclusion-across-europe-challenges-and-opportunities (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Agency for the Development of Education for Pupils with Special Educational Needs Educative. Teacher Education for Inclusion—Profile of Inclusive Teachers; European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education: Odense, Denmark, 2012; Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/teacher-education-inclusion-profile-inclusive-teachers (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Rouse, M. Reforming initial teacher education: A necessary but not sufficient condition for developing inclusive practice. In Teacher Education for Inclusion. Changing Paradigms and Innovative Approaches; Forlin, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cotán, A.; Cantos, M. Análisis de la formación docente en relación a las necesidades educativas del alumnado en las aulas. Poly. Rev. Educ. Int. 2020, 4, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Serrano, J.M.; Alba-Pastor, C.; Zubillaga del Río, S. La formación para la educación inclusiva en los títulos de maestro de educación primaria de la universidades españolas. Rev. Educ. 2021, 393, 321–352. [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner-Guasp, J.J.; Mut-Amengual, B.; Pinya-Medina, C. Formación inicial en inclusión en los grados de maestro en Educación Primaria. Siglo Cero 2021, 52, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, R.; Wehner, A.; Lohaus, G.; Krämer, P. Pre-service Teachers’ Beliefs about Inclusive Education before and after Multi-Compared to Mono-professional Co-teaching: An Exploratory Study. Front. Educ. 2019, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, R.; Wehner, A.; Lohaus, G.; Krämer, P. Effect of same-discipline compared to different-discipline collaboration on teacher trainees’ attitudes towards inclusive education and their collaboration skills. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 87, 102955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampieri, R.H. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; Mc Graw Hills: Mexico, DF, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Investigación Educativa. Una Introducción Conceptual, 5th ed.; Pearson Educación, S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, H. Qualitative Data and Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) Introduction: Entering the field of qualitative research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publication: California, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnaiz-Sánchez, P.; De Haro-Rodríguez, R.; Caballero, C.M.; Martínez-Abellán, R. Barriers to Educational Inclusion in Initial Teacher Training. Societies 2023, 13, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020031

Arnaiz-Sánchez P, De Haro-Rodríguez R, Caballero CM, Martínez-Abellán R. Barriers to Educational Inclusion in Initial Teacher Training. Societies. 2023; 13(2):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020031

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnaiz-Sánchez, Pilar, Remedios De Haro-Rodríguez, Carmen María Caballero, and Rogelio Martínez-Abellán. 2023. "Barriers to Educational Inclusion in Initial Teacher Training" Societies 13, no. 2: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020031

APA StyleArnaiz-Sánchez, P., De Haro-Rodríguez, R., Caballero, C. M., & Martínez-Abellán, R. (2023). Barriers to Educational Inclusion in Initial Teacher Training. Societies, 13(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020031