1. Introduction

Western democracy permanently values the role of vigilance and transparency that the press plays in society. Professional and academic debates on the role of the media as instruments of accountability, transparency and trust have been pillars of journalism, but the disruptive force of technologies in the media has been ignored in the context of the rise of platforms that promote broadcasting based on propagation algorithms [

1]. This new juncture is greatly complexified by the viral phenomenon of fake news. The problem of fake news is a critical incident being faced in Latin American journalism [

2,

3] and the world [

4,

5]. Tandoc et al. [

6] found that US news organizations recognize fake news as a social problem and that they blame the polarizing political climate of recent years, the inaction of big tech and the audiences themselves for their viral contribution. Nevertheless, it is also true that the media also execute actions such as: delivering general definitions about the phenomenon, exposing critical editorials that reflect on informative junctures, denouncing cases of fake news, promoting public debate, advising or educating for the detection of fake news and disseminating scientific studies on the subject [

7].

The circulation and propagation of falsehoods has been a long-standing concern for society. The old rumor theory dates back to the 1940s, when Allport and Postman [

8] described the processes of leveling, sharpening and the assimilation of rumors transmitted in human groups. Kapferer [

9] mentioned the iconic case of the Villejuif pamphlet, detected in 1976 in France, which remains in time and has new remakes. Such a pamphlet classically spreads information about food products and their carcinogenic components, building a mass rumor that almost always works. Thus, nowadays it has been proven that fake news, being novel, spreads faster and more extensively than real news on social networks [

5]. Furthermore, with the recent events linked to the coronavirus pandemic, it has even been proposed that we are also facing an infodemic that has been emotionally favored by the fear of the unknown [

10]. Therefore, the arrival of the pandemic made the development of research oriented to fake news and health more urgent [

11,

12,

13] and artificial intelligence has developed numerous efforts to detect, in an automatic way, false news about COVID-19 [

14,

15,

16].

In the latter, studies on fake news and politics also abound [

4,

17]. There is a significant body of research that has been oriented to relating the iconic political campaigns of recent times and the phenomenon of fake news and disinformation. Grinberg et al. [

18] found that during 2016 (the Donald Trump campaign), the individuals most likely to engage with fake news sources were conservative-leaning, older and highly engaged with political news on Twitter. They also noticed that a group of fake news sources shared audiences on the far right, but for individuals across the political spectrum, most exposure to political news still came from mainstream media. Particularly in Chile, phenomena related to fake news and its technological enhancers [

19] have also been studied in electoral processes. Halpern et al. [

20] developed an interesting study which collected, from a psychosocial perspective, the explanations given by Chileans when it comes to exposing themselves to, believing and sharing fake news.

4. Results

4.1. The Phenomenon in the Three Social Networks

The first research question sought to reveal which social network is most frequently used by the media to address the issue of fake news.

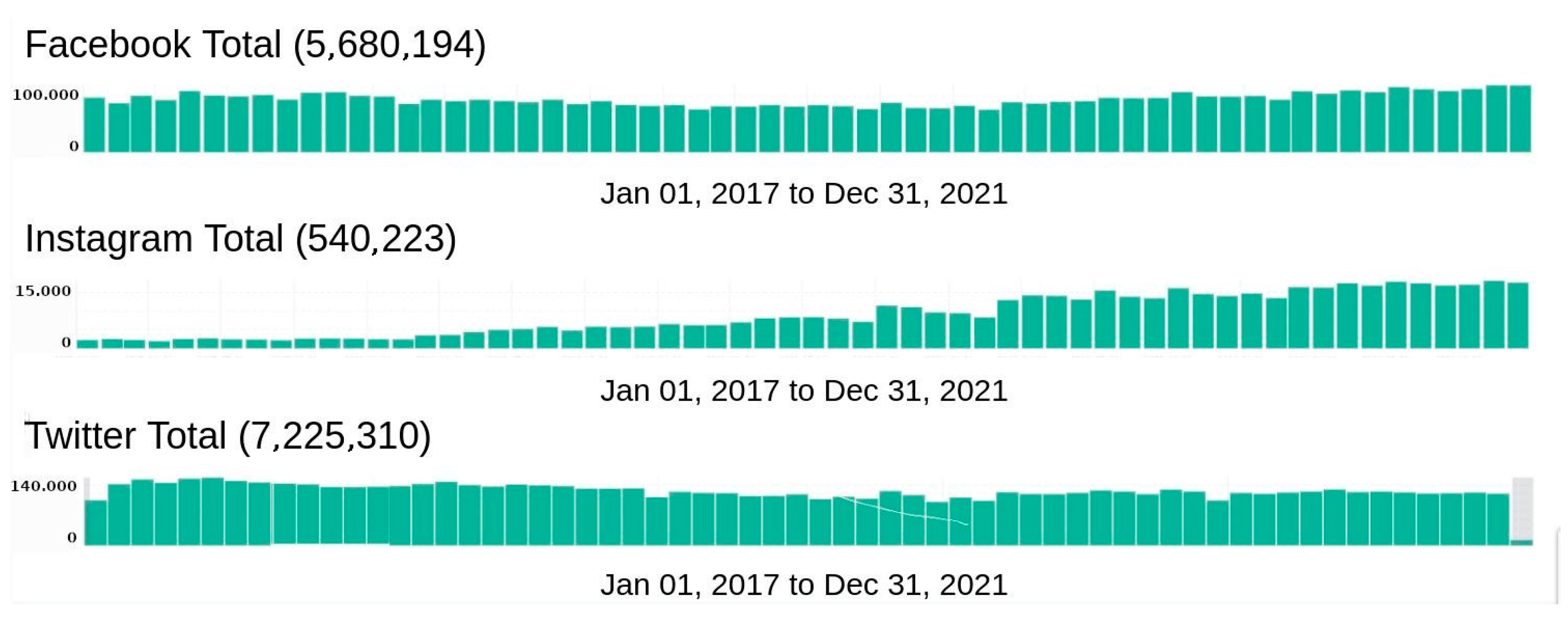

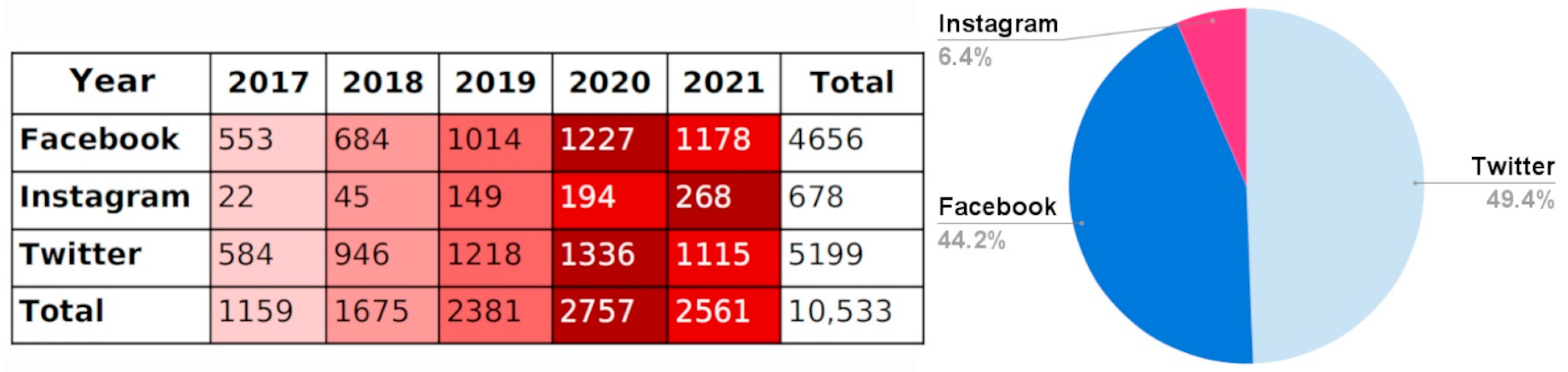

Figure 2 shows that 5199 posts were obtained on Twitter, 4656 informative posts on Facebook and 678 on Instagram. The intensity of red samples lower or higher publication frequency for each social networks.

Twitter is the network that is frequently the most used to talk about fake news. While this result is not surprising, it is interesting to note that Instagram seems to show a steady upward trend throughout the period, while Facebook and Twitter decrease in the raw number of posts referring to the topic in 2021.

4.2. Evaluative Metrics for Automatic Topic Detection

We set out to understand what the media refer to when they talk about fake news in their social networks or what general topics are observed. Due to the dissimilar characteristics of the length of the texts and the weight in the composition of the total corpus (see

Figure 2), it was considered appropriate to perform a separate analysis for each social network. It is also necessary to evaluate the quality of the results in the automatic language processing procedures.

Some metrics available to analyze the results of topic detection are equations such as perplexity, coherence and diversity. Firstly, perplexity represents the robustness of the topic model, i.e., the ability it has to determine topics associated with texts that have not been used to fit the model. The lower the perplexity value, the higher the robustness of the model. On the other hand, coherence is a measure of the co-occurrence in the texts of the words defining a topic. It is usually calculated for the top 20 words of each topic. Higher values indicate greater coherence. The UMass coherence metric takes values less than zero since it is the sum of negative values. In effect, each term of the summation is calculated as the logarithm of the joint occurrence rate of each pair over the occurrence of one of the words in the pair. This rate is always less than 1 and thus, the score is always negative.

In turn, diversity represents the proportion of top words that are unique to each topic. Thus, higher diversity values indicate more dissimilar topics.

Table 1 allows the understanding that the diversity of words is relatively similar in both Twitter and Facebook texts. In addition, it clarifies that the Twitter corpus is the one that yields the least perplexity and that the set of Instagram texts offers the greatest coherence.

4.2.1. Analysis of Facebook Topics

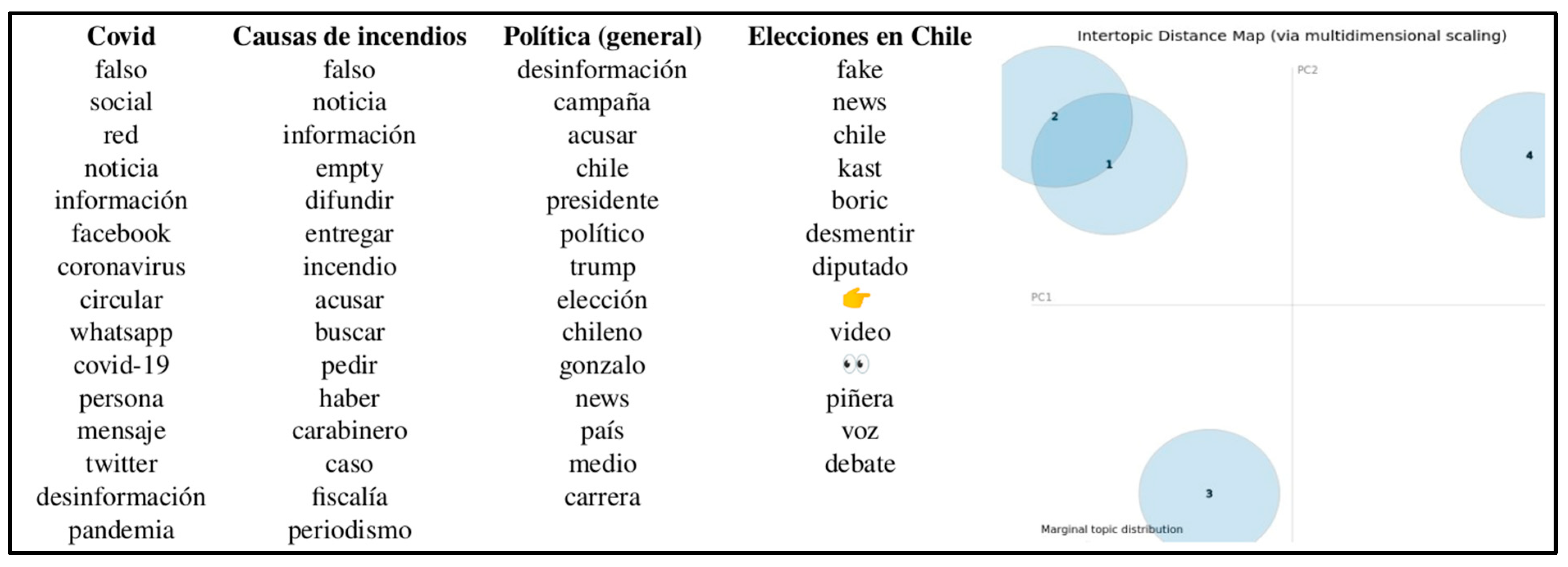

Four topics were obtained, which turned out to have significant equivalence (See

Figure 3). As expected, the first topic responds to the disinformation regarding the coronavirus pandemic (2020 and 2021). Such a cluster shares common elements with the second topic that refers to the disinformation that circulated before the wildfire events, which were a highly significant event in the summer of 2017.

The third topic responds to characters of politics in general; both international politicians are mentioned, as well as national ones such as Gonzalo de la Carrera. It is important to note that the presence of Gonzalo de la Carrera in fake news incidents is present in news at least since 2018, when the then-radio broadcaster spread false news about the then-deputy Camila Vallejos. CNN Chile then headlined “Gonzalo de la Carrera spreads lies linking Camila Vallejo and Simone de Beauvoir to pedophilia”. This case was prosecuted by Congresswoman Vallejo, who ended up losing the lawsuit in 2019; “Camila Vallejo lost the lawsuit for slander against Gonzalo de la Carrera for fake news” (El Mostrador). The fourth topic refers mainly to national electoral events.

4.2.2. Analysis of Twitter Topics

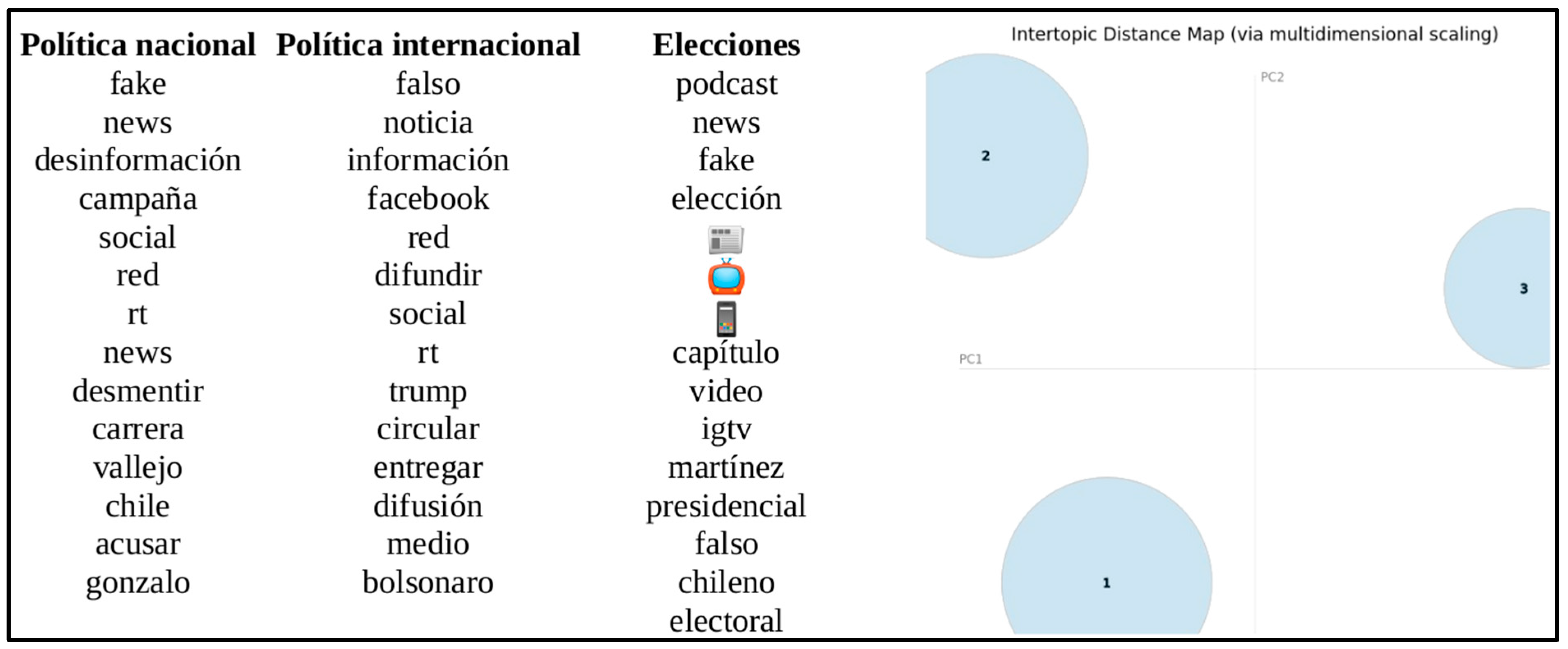

Although the volumes of posts are similar between Facebook (4656) and Twitter (5199), it must be borne in mind that the texts on Twitter are almost always more concise. In general, the fake news phenomenon on Twitter seems to be mainly oriented towards political issues.

The first topic refers to national politics, particularly to the public slander of Gonzalo de la Carrera towards Camila Vallejo, a case that was covered by the press between December 2018 and March 2019 (See

Figure 4). Said case involved a judicial process that was not able to punish the injurious behavior of the Agricultura radio station broadcaster. The second topic refers to international politics, where characters such as Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro gain evident prominence. The third topic refers to the Chilean electoral processes developed in 2020 (primaries, first and second round). It is noteworthy that in this topic, the surnames of the presidential candidates are not identified among the most valuable words.

4.2.3. Analysis of Instagram Topics

The corpus of posts referring to fake news and disinformation turns out to be reduced (678). However, the format conditions of this social network invite the media to incorporate, in general, a complete lead of the news in its description; therefore, each post turns out to be a fairly cohesive text and a good synthesis of the news event. That should be noted, as observed in

Figure 1 of this study. The use of Instagram is expressed in a growing and sustained way in the 159 Chilean media observed.

The first topic refers to misinformation about vaccines (See

Figure 5). The second cluster highlights the presence of José Antonio Kast and the presidential campaign process. Although the context does not seem clear enough to determine, it is believed that the third topic might be related to cases in which the police were involved in staging situations (for example, during the social outbreak of 2019).

To summarize, it should be noted that the automatic analysis models seem to behave very well in determining big themes. However, in terms of communicative functions, few communicative purposes are basically observed, and in this respect, these analyses are less diverse than the manual model applied [

7].

4.3. Multimodal Discourse Analysis

In order to achieve a necessary methodological complementarity [

36], a multimodal discourse analysis of a reduced but very relevant set of 30 publications was also developed. The top 10 interactions for each social network were extracted and analyzed (see in

https://github.com/luiscarcamo/Corpus_PLU210013 accessed on 1 January 2023). In other words, the posts were ranked in decreasing order (from the one that got the most reactions to the one that got the least) and then the 10 most popular posts on each social network were selected. On the one hand, the presence of narrative or conceptual images will be analyzed [

41]. On the other hand, we will try to identify the construction of news values [

42] (see

Table 2) in this dataset.

On Facebook, three out of 10 posts are concerned with rectifying (or announcing the rectification that takes place on the media outlet’s website) the facts on which the fake news is based. Specifically, the first post in order of interactivity clarifies that the alleged “fake images” associated with the storage of bodies in freezers resulting from the COVID-19 deaths in New York City are real (See

Figure 6). This post includes a narrative video whose news values are negativity, superlativity and impact, in that they exaggerate morbid details and seek the emotional reaction of the audience, in such a way that the images play a function of evidence and sensation in relation to the written text. Thus, the ultimate goal of the news is not to inform about the development of the pandemic, but to give a lurid treatment that instills fear in the population.

Conversely, the second and eighth posts in order of interactivity correspond to the national thematic area and focus on events that alter the social order or security. For example, it is clarified that the alleged montage behind the burning of Transantiago buses in a day of protests framed in the social outbreak of 2019 corresponds to fake news, but it is not indicated who the real perpetrators of the attack are in the text of the post. Here, a conceptual image is exhibited where the news values of negativity, superlativity and impact also prevail, establishing a sensation function with respect to the written text with similar purposes to those of the previous video.

Finally, two of the 10 posts that make up the total corpus address the dissemination of fake news and disinformation as a social phenomenon [

7]; that is, only two media with a presence on Facebook focus on addressing this reality as a problem to be contained and reversed involving public and private agents. These are the fifth and seventh posts in order of interactivity: an editorial by Mónica Rincón and Daniel Matamala from CCN Chile, and a Reuters Institute study collected by Interferencia. The first consists of a video where both journalists warn about the dissemination of fake news through social networks in the context of the forest fires that took place in January 2017. In turn, the second one warns about the increase in citizen distrust towards the press and the media of the business elite.

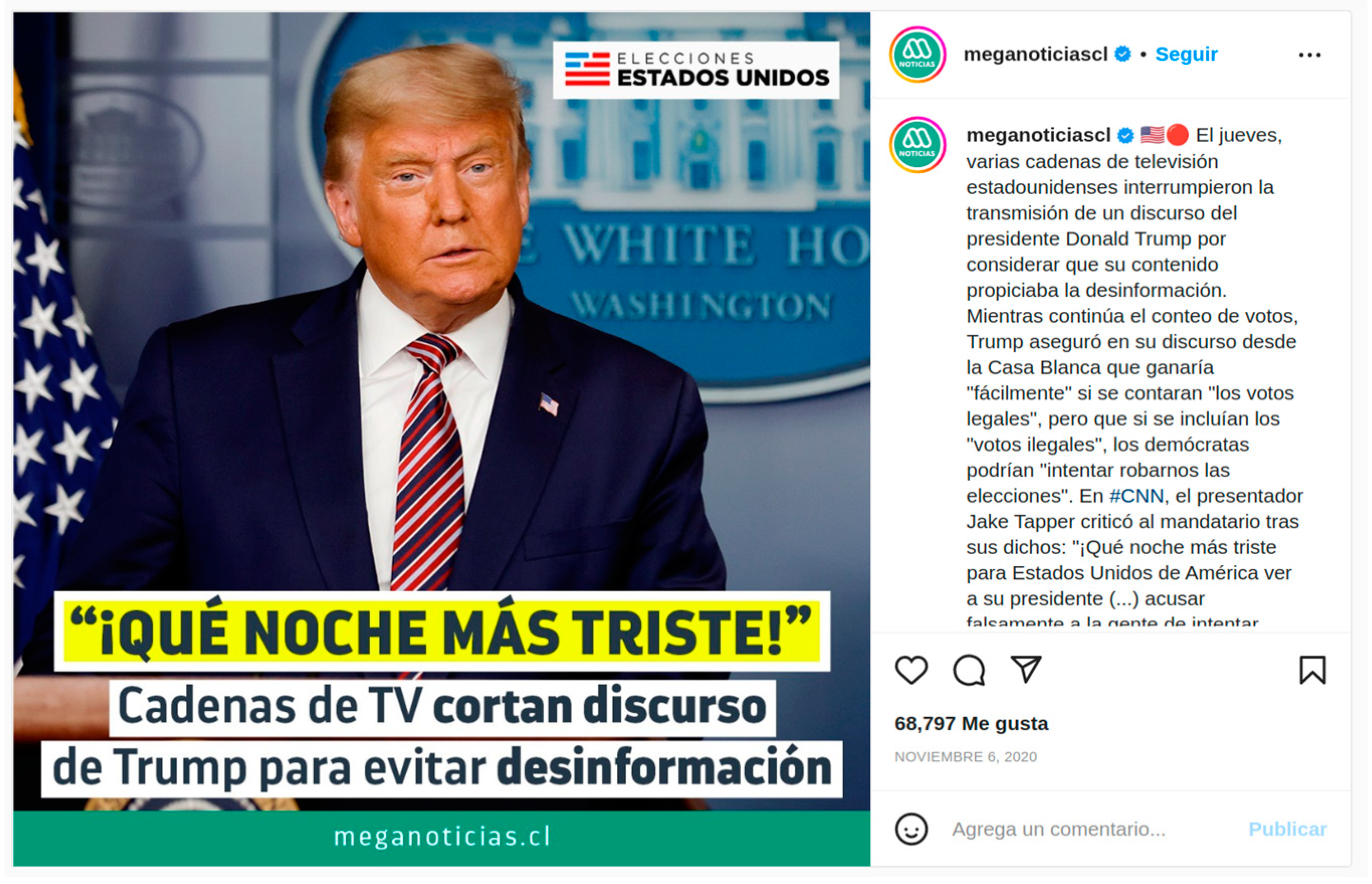

On Instagram, six out of 10 posts are dedicated to rectifying the facts behind the proliferation of fake news and disinformation. Of these, four are national in scope and two are international in scope. The breakdown indicates that two are miscellaneous in nature, two target the thematic area of technology and the remaining two deal with politics and society, respectively. On the one hand, three posts related to the pandemic stand out, which show the measures adopted by companies such as Youtube and Facebook to contain disinformation coming from anti-vaccine movements, as well as clarifications regarding the correct use of face masks. In these cases, conceptual images are used to illustrate the written content through logos and infographics, whose news values correspond to temporality and proximity criteria typical of the health contingency. On the other hand, two posts related to the local reality stand out: one about the presidential elections of 2021 and the other referring to police procedures in the context of the social outbreak. In both cases, the written content is illustrated by means of narrative images: one where the candidates Gabriel Boric and José Antonio Kast appear participating in the last televised debate, and the other of two Chilean police officers deployed in the middle of a demonstration. The first focuses on the news values of prominence and consonance, as it shows these two public figures from standardized visual patterns that enhance their rivalry; in this scenario, between the image and the written text, there is a relationship of co-contextualization, that is, of coherence and complementarity of meanings, since the headline “Boric gives a coup with drug test and neutralizes Kast with his fake news script” is portrayed in the reaction captured by the photograph. Unlike what is found on Facebook, Instagram posts are more regularly devoted to explaining data or background information aimed at counteracting the spread of misinformation and fake news, but it applies more to international than national issues. Thus, the post that obtained the most interactions on Instagram refers to the fact that American TV stations cut Donald Trump’s speech in the middle of the vote count (See

Figure 7).

On Twitter, five out of 10 posts seek to rectify or verify facts around which fake news are built. One post corresponds to the account of a journalist, while the other four correspond to the accounts of presidents or government authorities. The bulk of the posts consist of retweets from national or local media, so the work of corroborating these contents is rather indirect. In addition to these posts, there is one that addresses the dissemination of disinformation as a social phenomenon. However, it emanates from the Argentine government and is retweeted by President Alberto Fernández; it is a conceptual video where the infodemic raised by COVID-19 is addressed. In fact, three of these 6 posts follow the same line, while the remaining three hold certain public figures responsible for the proliferation of fake news. In these cases, the use of images is marginal since the denials are mainly made through written text.

For example, in the national sphere, The Clinic highlights a news item where several fact-checking websites accuse extreme right-wing candidate José Antonio Kast as the main actor responsible for spreading false information during the Anatel’s presidential debate (See

Figure 8); here, the narrative image is merely illustrative as it portrays the candidate and confers him a news value of prominence. Another of the posts includes a statement from the Constitutional Convention that is retweeted by its former vice-president Jaime Basa, denying the alleged discussion around limiting fruit exports. Consequently, although on Twitter there is more room to confront the circulation of fake news, the media only limit themselves to making visible the denials made by certain political actors.

4.4. Politics and Health at the Center of the News

In the cases of news about politics, two recurrent phenomena occur: (1) these figures have the opportunity to rectify their statements, exonerating themselves of their responsibility as promoters of fake news (for example, “President Piñera clarifies his statements about certain ‘fake news’”), (2) or their statements are reiterated, ending up reinforced instead of verified or denied (for example, “José Antonio Kast in his campaign closing: ‘There is no fake news here, Mr. Boric, you are the falsehood’”). Thus, following the examples surveyed, @24horascl explains the context in which Sebastián Piñera declares that “the viralized records on the violent actions of some police officers during the social protests are ‘false’; they were recorded abroad and correspond to ‘fake news’”. However, they neither confirm nor discard the veracity of such records. In a similar vein, @cnnchile also explains the context in which Kast criticizes Boric as presidential candidate of the left-wing party Apruebo Dignidad, replicating an attack where he deliberately accuses him of facts that he frames by reason of his right-wing political ideology: “He is the one who wanted to pardon the vandals that destroyed Chile; he is the one who did not want to punish those who attack firemen and the very same one who got together with a terrorist murderer who assassinated Jaime Guzmán”.

Both the automatic analysis (LDA) of all posts and the multimodal discourse analysis (MDA) coincide in highlighting two relevant news focuses: politics and health.

In posts referring to health issues, the posts that meet these characteristics allude to the pandemic, as is occurring internationally with the deaths from coronavirus in 2020 (for example, “Get on your knees and pray… This is real. The dire situation the US is going through because of the coronavirus”) or the growth of anti-vaccine movements (for example, “YouTube to block and remove all anti-vaccine content”). In these cases, an interesting phenomenon is also observed. On the one hand, @Meganoticias does attempt to correct or verify the facts around which this purported fake news is circulating, but this goal is only achieved if several minutes of the video are watched. At first glance, however, it is not clear whether the report of piling up bodies in freezer trucks is true or false. On the other hand, @cooperativa reports on the measures that Youtube will take to delete any incorrect content about vaccines that the World Health Organization and local health authorities have confirmed to be safe; however, this clarification is included in the text of the post, not in the headline or in the accompanying image. Given these examples, it would seem then that the media are more concerned with providing a shocking or sensationalist treatment of information regarding the COVID-19 emergency, rather than systematically verifying or challenging sensitive content for the benefit of the population. This raises questions about the criteria governing journalistic practice when it comes to countering the effects of fake news.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

It was found that the social network most frequently used by the media to talk about fake news is Twitter, followed by Facebook and, to a lesser extent, some posts on Instagram. Broadly speaking, the analysis of topics allows observing variations in social networks. While the information posted on Twitter concentrates the topics around political issues, the news circulated through Facebook and Instagram seem to open other focuses on the coronavirus, vaccines and forest fires.

Furthermore, when the media talk about fake news on their social networks, they mostly refer to politics (electoral contexts and statements by politicians in general) and health issues (coronavirus, vaccination, false remedies). Furthermore, the topics that incite the spread of fake news and/or disinformation are mainly linked to politics (presidential elections in Chile and the USA). They are followed by the health of the population (coronavirus pandemic, anti-vaccine movements), namely, issues that trigger social polarization, fear or generalized morbidity [

3,

9,

21] and situations where order or national security is at risk (social outbreak in Chile).

In general, it is observed that the phenomenon of fake news and disinformation occupies an increasingly salient place in current press broadcasts in general, being an evident phenomenon in electoral periods [

5] or in situations of political or social upheaval, given that they penetrate better as long as there is a pre-existing tension in society [

24]. This is confirmed in the manually analyzed subcorpus, in relation to the presidential elections in Chile (Boric vs Kast) and the United States (Biden vs Trump) and the COVID-19 pandemic, which occupied a large portion of the most interactive posts. This situation invites one to revisit the social responsibility of the press in the face of echo chambers and bubble filters [

4]. Indeed, the understanding of the phenomenon and its consequences require greater rigor and commitment to journalistic values and their relevance for democracy [

6].

In most cases, the media focus on replicating controversies involving the dissemination of fake news or false information, especially when they come from national and international political authorities. However, only on some occasions do the media (especially on Instagram and Facebook) and certain public figures such as presidents and journalists (mainly on Twitter) focus on denying or rectifying such broadcasts; for instance, when public health is at stake.

Unlike the results obtained previously and with a smaller corpus [

7], the bulk of the posts cover information involving the circulation of fake news, instead of addressing them as a social phenomenon that should be confronted through ethical, educational and legal actions undertaken by the media and other public or governmental entities. In the analyzed sample, at least, the media are not identified or alluded to as disseminators of fake news, nor is it evident that they carry out systematic fact-checking work.

Moreover, the images selected by the Chilean media in social networks when dealing with fake news also play a significant role. The multimodal discourse analysis enables the realization that, on the one hand, when the dissemination of false news and/or disinformation involves recognized public figures (either national or foreign), such as candidates, parliamentarians or government authorities, narrative images or videos are used where they appear as speakers in verbal processes that require the reproduction of direct or indirect quotations. Images or videos of this type are the majority in the sample, and their selection is explained by the preference of the national media to give coverage to political figures involved in controversies due to their statements; that is, those who stand out for their prominence as news value. In general, the media echo these controversies, but do not contribute to clarifying the underlying information. Likewise, in these posts, the relationship between written and visual content accounts for an illustrative function and it reveals a relationship of co-contextualization; that is, the meanings constructed by both semiotic modes are mutually reinforcing and transparent (self-evident and non-questionable) for the audience.

On the other hand, when fake news and/or misinformation refer to concrete events whose news value is usually given by their temporality, negativity or superlativity, they are represented in narrative images or videos that play a sensation or evaluation function. That is to say, they pursue an emotional or moral response in the audience. Unlike the cases mentioned above, a relationship of re-contextualization is built between the visual and written modes, since what is sought to be explained with the text is not immediately evident in the images or videos. This gives more room for manipulation or misinterpretation, as certain information is disproved from true records, which tests the users’ capacity for comprehension, as they must distinguish and associate the meanings created in each semiotic mode in order to understand them correctly.

To conclude, at the end of the analysis, it is worth reflecting on whether or not the press deals adequately with the phenomenon of fake news. Replicating sayings or polemics qualified by political figures as fake news is not the same as clarifying disinformation. In contexts of polarization, the media should focus on clarifying and not only behaving as privileged exhibitors of opinion leaders. It may seem objective to do so; however, citizenry and democracies require not only good showcases of facts, but also quality information for the generation of informed opinions and the construction of increasingly democratic societies. Politics and pandemic became the perfect combination to cultivate disinformation in the last five years of the Chilean context and the media seems not to find its way to contribute effectively.

Limitations

Although in this study we collected a large dataset coming from 159 relevant news sources, it is important to highlight that this study does not cover all the mentions about fake news on social networks. For example, our approach does not include the mentions about fake news done by politicians or other public figures in their personal accounts. Probably, that dataset would be different, and require a completely new analysis.

Also, it is important to call out that we are not considering the full text of news articles but just their snippets on social networks. The full article might contain more, and richer, information that could—for example—improve the quality of the topic detection models. Anyhow, we consider that the text on social networks is valuable for the goals of this study, moreover considering that nowadays, social networks are the most consumed sources of information.