Abstract

Intercultural communication is often affected by conflicts, which are not easy to resolve, mainly due to the clash of conflict communication styles. Direct/indirect ways to approach conflicts, emotional display/control, the ability to empathize and consider perspectives of others, cultural conventions, previous experiences with conflict, cooperativeness, and many other factors determine our conflict communication styles. It is important to acknowledge, though, that these styles are learned and are not rigid. They can differ depending on the context and situation. This article reports the results of an intercultural telecollaboration project, drawing on four sources of quantitative and qualitative data, i.e., the results of assessments conducted with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire, and a Conflict Styles Assessment based on the Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument, as well as students’ critical self-reflective feedback. The data were collected at a Mid-Atlantic minority-serving university from undergraduate students, who were invited to explore their conflict communication styles through a series of activities and then reflect on their experiences and the insights gained during this intercultural telecollaboration experience. As a result of this pedagogical intervention, most of the participants not only became aware of their conflict communication styles but also developed their empathy and ability to intervene to defend others who are discriminated against or attacked verbally.

1. Introduction

Conflicts are inevitable, even for those of us who try to avoid them. Conflicts arise in both professional and personal settings and exist at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community levels of engagement. Over our lifetimes, we will navigate conflict in close relationships (family, friendships, and business partnerships) as well as with people we do not have prior relationships with. However, the inevitability of conflict is not inherently negative. Developing the ability to deal effectively with conflicts and mindfully apply an appropriate conflict communication style may cardinally change the outcome of a conflict situation.

Research on styles of conflict resolution and communication is an interdisciplinary topic explored within various research fields including psychology, business management, communication studies, and others (see, for example, [1,2,3,4,5,6]). While these disciplines study conflict through different paradigms, there is agreement that understanding one’s conflict communication style and developing skills to navigate conflict situations is valuable for individuals, organizations, and communities. Moreover, encouraging constructive engagement with conflict aligns with the broader goals of higher education and contributes to fostering empathy, critical self-reflection and self-awareness, communication skills, and intercultural citizenship.

In the context of higher education, there are diverse ideas about what the core purpose of higher education is. There are those who believe it is a public good and a site for raising critical thinkers [7,8,9], those who believe its purpose is to create a democratic public sphere and to educate intercultural/global citizens [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], and those who believe in the neo-liberal model and that higher education should solely focus on equipping students with the skills they need to be successful employees (see the article by Lynch [18] for a critical discussion). Regardless of one’s beliefs about what the purpose of higher education is, students having the opportunity to understand their conflict communication style and develop conflict-resolution skills could contribute to a university achieving its broader goals.

Unfortunately, despite their broad application, the opportunities for students to learn about their conflict communication styles and to develop conflict-resolution skills while studying at university are quite scarce (unless students are enrolled in a Master’s or Doctoral program specifically focusing on conflict resolution). Additional research is needed to identify (1) effective curriculum and pedagogical approaches for teaching conflict-resolution skills to university students and (2) how increased opportunities for learning conflict-resolution skills impact a student’s experience on campus. This study was motivated by findings from the Enhancing Student Engagement in Internationalization at Home: Towards Inclusiveness and Intercultural Dialogue project 1 (hereafter referred to as the Hrabowski Innovation Fund (HIF) project, see [13] for details) and offers suggestions for future research.

2. Background and Theoretical Framework

Recently, a multidisciplinary group of scholars at a Minority Serving Institution (MSI) in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States developed the InterEqual training modules as part of a three-year HIF project. In 2022, the InterEqual training was piloted with more than 200 undergraduate students across all degrees, with a plan to extend it to all levels of study as well as to university staff and faculty.

This training is an innovative new approach to intercultural communication education with a focus on developing competencies for democratic culture and intercultural citizenship, which we consider an essential attribute of a modern professional [12]. The HIF research group that I led sought to develop a training program that helps increase student perceptions of campus inclusiveness in terms of rich diversity across ethnicities, races, language backgrounds, ages, genders, sexual orientations, and ideological and religious beliefs and in terms of disabilities and other demographics.

The InterEqual training program consists of five self-paced online modules, with one module specifically dedicated to exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts. When developing the InterEqual training, we incorporated student feedback collected through a campus-wide survey [13].

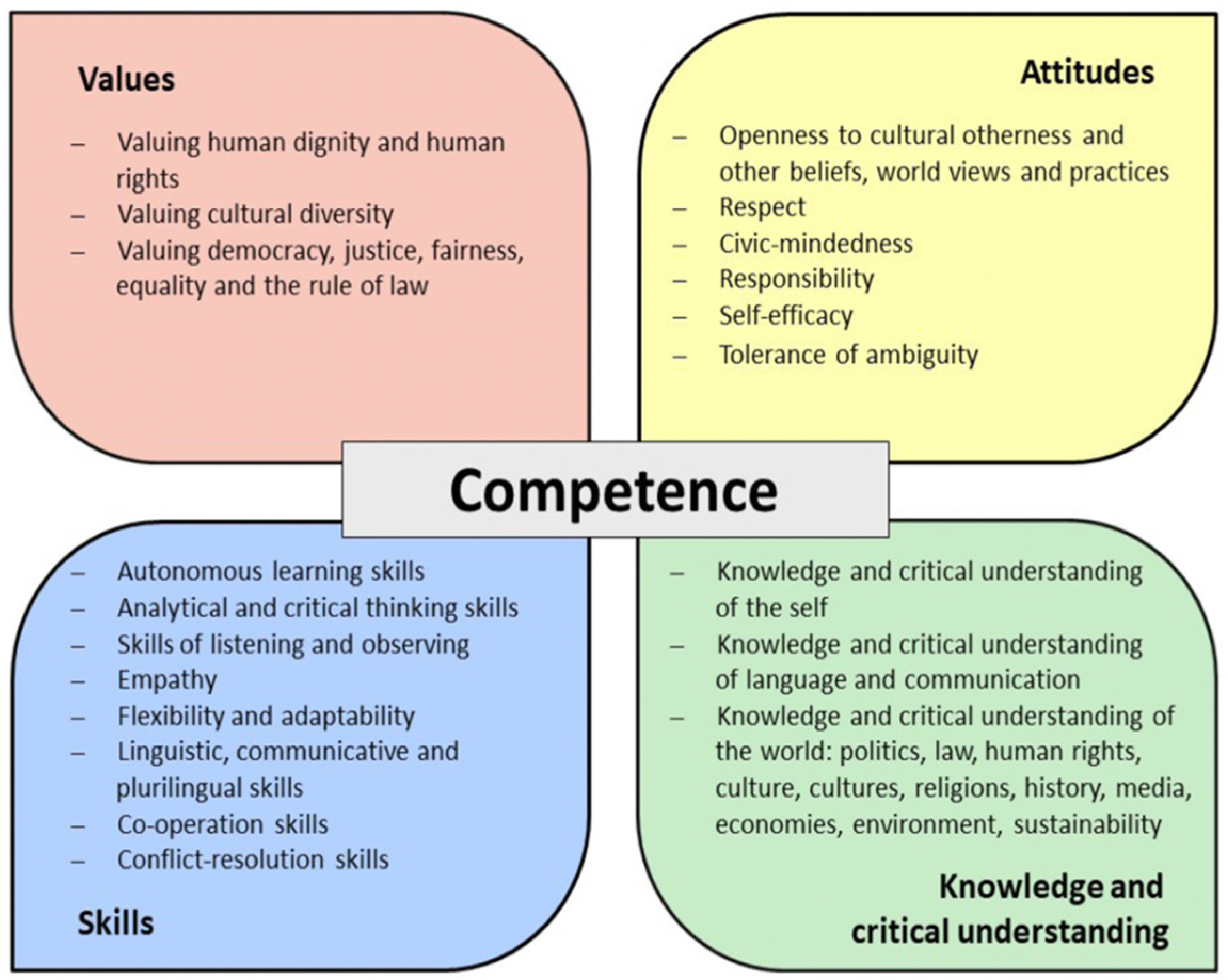

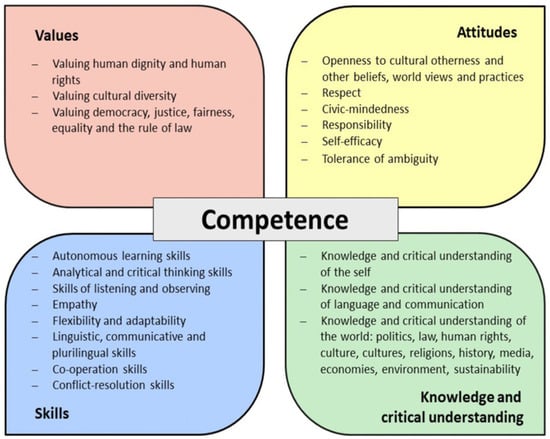

As the theoretical framework for the survey, our project team used the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC) [19]. The RFCDC model consists of four sets of categories, with 20 categories in total: values (3), attitudes (6), skills (8), and knowledge and critical understanding (3) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The 20 RFCDC competences. Reproduced from [19] (p. 38) with permission. © Council of Europe.

Our project team chose this model, among many other existing models and frameworks, because it combines the competences for democratic culture with a strong intercultural focus. In educational settings, the RFCDC can be used to equip students with the values, attitudes, skills, knowledge and critical understanding needed to sustain equity, inclusion, and social justice and to live harmoniously with others in culturally diverse communities [19]. The framework was used to design a questionnaire that collected students’ perceptions and experiences on campus (see [13] for details). Based on the survey findings, our HIF project team identified the major gaps and developed the InterEqual training to address the gaps.

A lack of opportunities to develop conflict-resolution skills was a major finding of the survey. When the MSI students were asked which of the twenty values, attitudes, skills, and areas of knowledge and critical understanding they had the opportunity to develop at the university, conflict-resolution skills were ranked at the bottom of the list and were mentioned by only a third of all respondents. When they were asked which of the twenty competences they would like to develop (further) while studying at the university, conflict-resolution skills were the most requested area, with more than 50 percent of respondents listing them. This gap between what was offered to the students and what they needed for their life, academic, and career success served as the rationale for dedicating one of five InterEqual training modules to the topic of conflict-resolution skills and was a main motivation for this separate study.

There are many findings coming from the pilot of the InterEqual training modules. The study reported in this paper was launched, first, to examine the effectiveness of the InterEqual training module on “Exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts” specifically in terms of increasing students’ empathy; second, to investigate whether the context of an intercultural telecollaboration project would affect students’ conflict communicative behavior and commit them to more collaborative behavior in conflicts; and third, to evaluate the effectiveness of the pedagogical intervention, which combines work on an intercultural telecollaboration project with completing the InterEqual module on conflicts. The purpose of this intervention was to raise students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles. The findings show how the pedagogical approach taken in this study can be applied in the field of intercultural citizenship education and to foster diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice on university campuses.

3. Raising Students’ Self-Awareness of Their Conflict Communication Styles

Prior research suggests that self-awareness is an important factor in conflict resolution. Developing self-awareness helps people to approach conflict constructively by managing their emotions and developing more mindful communication strategies [20,21,22]. Moreover, as emphasized by Blakemore and Agllias, “[t]he intentional scaffolding of self-reflective activities can support [conflict communication] skills development and promote self-awareness” [23] (p. 21). I view self-awareness as a critical component of intercultural communication training modules in general, but it is especially important in teaching about conflict resolution.

In this study, I used the definition of self-awareness offered by Carden and colleagues:

“Self-awareness consists of a range of components, which can be developed through focus, evaluation and feedback, and provides an individual with an awareness of their internal state (emotions, cognitions, physiological responses), that drives their behaviors (beliefs, values and motivations) and an awareness of how this impacts and influences others”[24] (p. 164).

Defining self-awareness can be straightforward, but as a recent literature review of self-awareness in the context of adult development showed, the complex and multidimensional nature of the construct “is hindering theorizing on how self-awareness should be taught and assessed” [24] (p. 141). For the purpose of this research, as well as in my teaching practice, I adopted the approach that self-awareness can be attained through systematic critical self-reflection in the context of experiential learning 2, more precisely, through a specific type of experiential learning—cooperative group work. This way, students engage in both intrapersonal and interpersonal interaction simultaneously.

Cooperative learning has been widely utilized for the past six decades, and its effectiveness has been empirically proven (see [26] for an overview of the benefits of cooperative learning). Research shows that studying cooperatively with peers results in increased perspective-taking skills [26], i.e., the ability to adopt the points of view of others [27], and has a positive effect on empathy [28], defined as the ability to understand and interpret the feelings and experiences of others [27] and to react to them appropriately [29]. In cooperative situations, conflicts typically arise over the best way to achieve common goals and, therefore, tend to lead to a variety of positive outcomes, namely, constructive engagement in integrative negotiations, peer mediation, higher achievement, and more accurate perspective taking [26,30].

Combining cooperative learning with critical self-reflections (e.g., journaling, feedback, self-assessment, etc.) is crucial in my pedagogical approach. Critical self-reflection—defined by Mezirow [31] as the process of questioning one’s own assumptions, presuppositions, and meaning perspectives—increases one’s self-awareness [32], which potentially increases one’s awareness of the need to respond in an empathic way [33]. Additionally, critical self-reflection helps students connect their experiences with module learning objectives and encourages further personal growth [34,35].

The current study hypothesized, first, that the completion of the InterEqual training module, which includes work on an intercultural telecollaboration project, would have a positive impact on students’ overall empathy level, specifically on empathy’s cognitive construct, perspective taking; second, that the context of an intercultural telecollaboration project would affect students’ conflict communicative behavior and commit them to more collaborative behavior in conflicts; and third, that the pedagogical intervention, which combines cooperative learning with critical self-reflection, would raise students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles. Thus, the research questions (RQs) for this study were as follows:

- RQ1: Does the completion of the InterEqual training module, which includes work on an intercultural telecollaboration project, increase (a) the overall empathy level and/or (b) a specific cognitive construct of empathy—the perspective-taking ability?

- RQ2: What is the prevailing conflict communication style in the context of an intercultural telecollaboration project?

- RQ3: Does the combination of cooperative learning and critical self-reflection have the potential to raise students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles?

4. Materials and Methods

This study analyzed data collected at a Mid-Atlantic minority-serving university in the United States from undergraduate students participating in a semester-long intercultural telecollaboration project. In addition to collaborating on small-group projects on “Enhancing Inclusiveness and Intercultural Dialogue on Campus”, students completed multiple scaffolded activities from the InterEqual training module on “Exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts” aimed at raising students’ self-awareness of their own conflict communication styles. The study participants completed a self-report assessment of their conflict communication styles and pre- and post-project empathy assessments. Qualitative data were collected via an online feedback survey.

Participation in the telecollaboration project was a crucial element of this pedagogical intervention for two interdependent reasons. First, it created a real-life opportunity to implement conflict-resolution skills: the telecollaboration project had several strict (and, therefore, stressful) deadlines, and students were put into groups with peers they were not familiar with, which helped stimulate potential conflict situations. Second, students had the opportunity to develop self-awareness of their conflict communication styles.

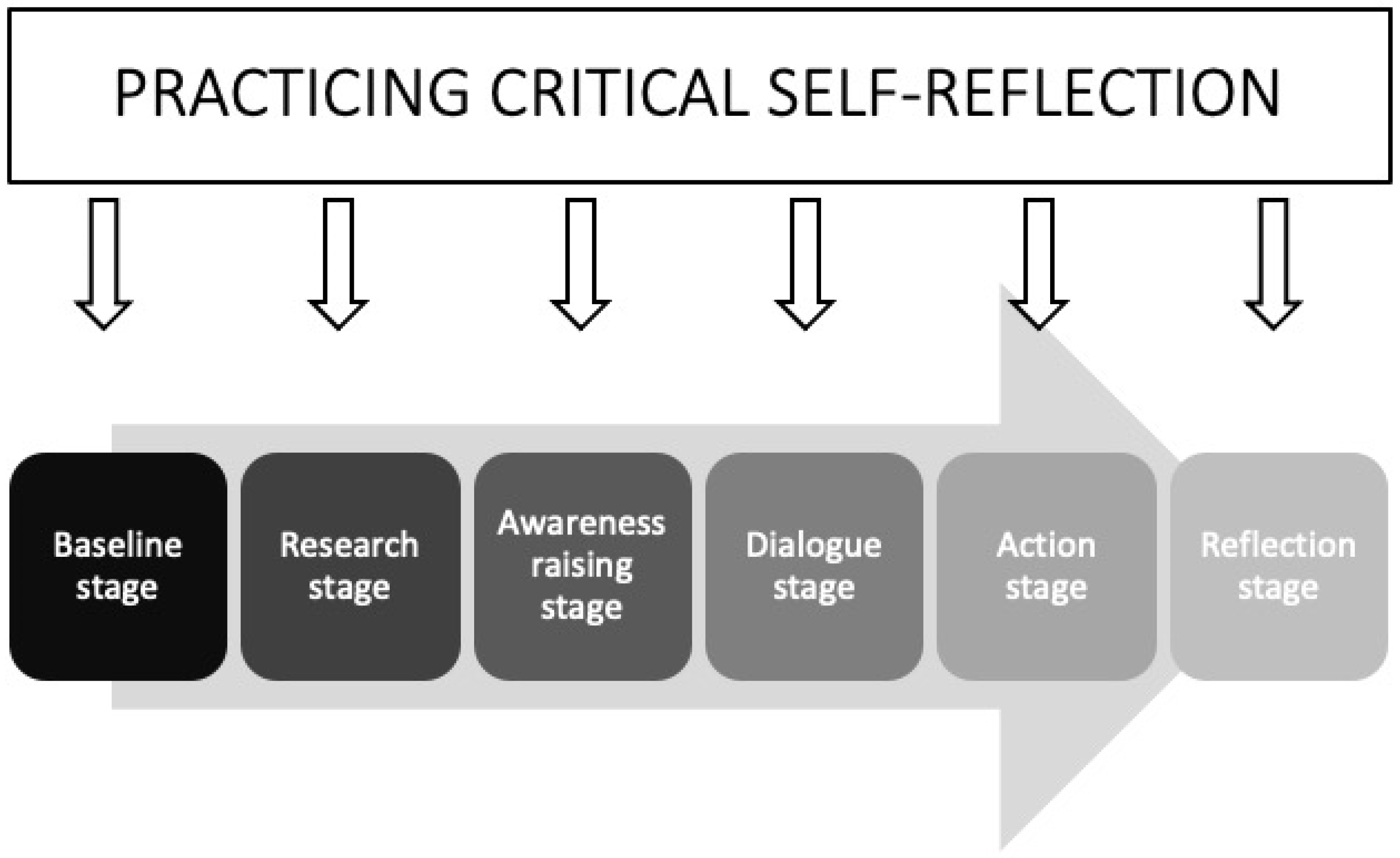

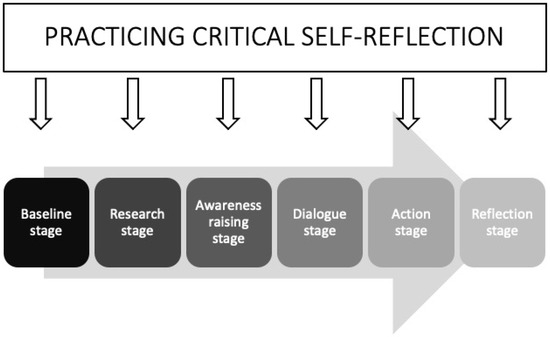

Following [17], the project was structured in six stages (see Figure 2), with critical self-reflection activities built in after each of the project stages, as suggested in [36].

Figure 2.

The sequencing of the project stages and the critical self-reflection activities (based on [17] and [36]).

In stage one (baseline stage), students began by completing the pre-project empathy assessments (Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) [27] and Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) [37]). After receiving their results, they critically self-reflected on how they could become more empathetic with people culturally different from them.

In stage two (research stage), they individually explored what students from different cultures understand to be an inclusive campus and collected examples of how the theme of inclusiveness had been expressed artistically on university campuses in the United States. After this stage of the project, students self-reflected on whether they felt respected, valued, accepted, cared for, and included at their institution.

In stage three of the project (awareness raising), students shared the examples they had individually collected with peers in their small groups. The small groups then jointly discussed the power of those art creations in conveying the idea of inclusiveness (or non-inclusiveness) on a university campus. Afterwards, students self-reflected on how these images may influence their thinking, feelings, emotions, behavior, and communication.

In stage four of the project (dialogue stage), the small groups engaged in a group discussion about how their joint artwork (e.g., a poster, a collage, etc.) would convey their feelings and/or thoughts regarding the inclusiveness of their campus. The small groups then shared their creations with the whole class to seek their peers’ feedback. Following this, students individually reflected on the process of creative telecollaboration and what they learned from and about others through this experience.

In stage five (civic/social action stage), students went “beyond the virtual classroom” by sharing the product of their artistic creation in a social media post, a blog, or any other online platform. The small groups had to draft their social/civic action statements together. Then, the students individually reflected on how they felt about completing this project stage and how their experience in the project related to their day-to-day lives.

Finally, in stage six (reflection stage), the small groups discussed what they learned about inclusion and intercultural dialogue during this project and shared whether their views about the inclusiveness of their campus were confirmed or challenged and whether they changed as a result of this telecollaboration. Students individually completed a brief reflection on their participation in this project by answering how they felt during telecollaboration, whether they had any types of conflicts, what the most eye-opening experience was, and how they intend to take any social/civic action in the future in order to improve the inclusiveness of their campus. At the end of the training, in addition to the post-project empathy assessments (IRI and TEQ), the students had to complete a Conflict Style Assessment based on the Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) [38].

All three types of assessments—the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ), and the Conflict Styles Assessment (CSA)—are self-report measures and were self-administered by the students. The students were offered the option of not sharing the results if they preferred not to. In total, 162 students shared their TEQ assessment results, 138 shared their IRI results, and 63 shared their CSA results.

For the quantitative data analysis, pre- and post-project measures of empathy were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If the empathy measures were normally distributed, paired t-tests would be completed using the pre- and post-project results. If the empathy measures were not normally distributed, a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test would be conducted on the pre- and post-project test results to account for non-normality. All statistical tests were performed using STATA/MP 17.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Quantitative Data

5.1.1. Normality of Empathy Measurements

The results of the Shapiro–Wilk test showed that the pre- and post-project test results for the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index—Perspective Taking (IRI—PT) were not normally distributed. Therefore, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to evaluate the TEQ and IRI—PT.

5.1.2. Changes in Empathy Measures

The analysis of the data collected through the self-administered Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (pre- and post-project tests) indicated that the overall score of the students’ (n = 162) self-perceived empathy increased after the pedagogical intervention. The mean TEQ score measured at the beginning of the training was 50.70 (SD = 6.59), and after the completion of the training, it was 51.86 (SD = 6.76). A mean increase of 0.41 in perspective taking measured with the IRI was also observed, and it was near significance (p = 0.09) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre- and post-project findings for empathy, measured with the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ), and perspective taking (PT), measured with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI).

Thus, the answer to the first part of RQ1—Does the completion of the InterEqual training module, which includes work on an intercultural telecollaboration project, increase the overall empathy level?—was yes, and this result was statistically significant.

Given that the increase in PT was near significance (p = 0.09), the answer to the second part of RQ1—Does the completion of the InterEqual training module, combined with work on an intercultural telecollaboration project, increase the perspective-taking ability?—was that an additional investigation with a larger sample size should be conducted before claims of changes in perspective taking can be made.

5.1.3. Conflict Styles

In total, 63 students shared the results of their Conflict Styles Assessment. Based on the self-reported responses, the vast majority (n = 50) self-assessed their style as collaborative problem solving, with the other 13 demonstrating either compromising, competing, avoiding, or accommodating conflict communication styles.

Hence, the answer to RQ2—What is the prevailing conflict communication style in the context of an intercultural telecollaboration project?—was collaborative problem solving.

Further investigation is necessary to understand if students’ pre-project TEQ scores can be used to predict their conflict communication style or if they impact the effectiveness of pedagogical approaches used in this study.

5.2. Analysis of Qualitative Data

To understand the potential of participation in an intercultural telecollaboration project combined with the completion of the InterEqual training module on “Exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts” to raise students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles, students were invited to share their feedback on three open-ended questions via an online form:

- How do you feel about completing this training module?

- What task did you enjoy the most? Why?

- How does this training module relate to the real world where you live?

5.2.1. Students’ Feedback on Completing the Training Module

Students highlighted the eye-opening effect of their learning experience. They became self-aware of their conflict styles and learned a lot about conflict resolution. The evidence is italicized in the excerpts from students’ feedback:

S4: [This module] taught me a lot about myself and how I interact with other people [...].

S11: I feel very glad to have completed [this] module as conflict resolution has always been unconscious for me, so a deeper analysis of my conflict behavior was much needed.

Students shared that they became more confident and learned how to approach conflicts in a more positive way.

S25: I feel more equipped to deal with conflicts confidently.

S29: [...] I learned new things that I did not know before. I am now able to recognize cultural differences, commonalities, perceptions, power and privilege dynamics, and how these differences can lead to conflict.

S30: I feel like I understand more about my conflict styles and lenses. It made me more aware of my approach and genuinely reflect upon the outcomes that some of my conflicts had in the past. I also felt a bit relieved that I got to dig deeper into things that I didn’t consider and why I do the things I do. I also felt a bit upset because the conflict style really showed me what kind of person I was in the past and how poorly I act when I argue with others.

Students reported that the module not only increased their self-awareness but also contributed to a better understanding of cultural differences and power dynamics and provided them with the confidence to intervene if someone is treated in an unjust, discriminatory way:

S12: [This] module [...] allows me to find solutions to intercultural conflicts and gives me new ideas on how to [...] intervene in these conflicts.

S34: I had a lot of takeaway points that I could improve in my own life. For instance, the assignment where we learned about having [the] confidence to speak up when in situations where someone is being verbally attacked really resonated with me.

The completion of the module also contributed to increasing students’ appreciation of compassionate curiosity and its role in communication and conflicts. Students also realized that empathy and perspective-taking skills can be developed:

S21: As human beings, we are always going to have thoughts and opinions. But being able to learn about the motives and reasonings behind those thoughts is what is really important, which is where compassionate curiosity comes into play.

S45: I feel very accomplished completing [this] module because I learned a lot of new concepts that I have not previously encountered in my other classes. For example, I did not use to think of empathy as a skill that can be developed. Instead, I used to think that either someone is empathetic or they are not. It was refreshing to learn that people can actually learn to be more empathetic by increasing the diversity of their interactions with others so they can better understand how people of different backgrounds think.

One of the most important outcomes of this training module was that the students were able to identify areas for self-improvement:

S6: I feel that I understand my conflict [...] style more and I know what I need to work on [...] to improve it.

S11: I liked [the activity on conflict styles] because it showed me where I needed to improve in order to become a better person.

S23: I feel as though I have a much better understanding of my own self in terms of how and why I deal with conflicts the way I do and how to refine it going into the future.

S38: [This module] gave me a good idea of what I need to work on to become a better intercultural communicator.

Overall, the students’ feedback was very positive. It not only offered insights into changes in their perceptions of conflicts and the role of compassionate curiosity but also provided them with an opportunity to exercise critical self-reflection.

5.2.2. Students’ Feedback on the Training Module Activities

The vast majority of the students agreed that the Conflict Style Assessment was the most valuable assignment of the InterEqual training module on conflict resolution:

S18: I most enjoyed completing the [task on] conflict styles. After completing the [...] conflict modes assessment, I was asked to investigate where I could have learned my conflict mode tendencies from. I immediately knew that I picked up on a few habits from my father. I thoroughly enjoyed making him take the assessment and seeing his reaction when we both had eerily similar results.

S30: Learning about these different conflict styles helped me get a better understanding of what my tendencies are in a conflict and what to stop and improve upon myself to be more considerate and compassionate towards others.

Some of the students specifically highlighted the activity on learning to intervene, stating that it was the most useful and that they can apply its content to their everyday lives:

S11: I enjoyed the “learning to intervene” activity the most. Attacks similar to that of the video aren’t unfamiliar to me as I have fallen victim to them simply because of my race. As a result, it was easy for me to write my reflections on the questions and speak on my motivations to intervene.

The students also highlighted the importance of learning about individualistic/collectivistic approaches to resolving conflicts:

S16: I liked completing [the task on individualistic and collectivistic conflict lenses] the most because I enjoyed learning about people and their views on individualistic and collectivist cultures. I believe it is quite beneficial for people to learn more about these topics because individualistic and collectivist cultures can learn a lot from each other. There are moments where it may be preferred to have an individualistic approach like defending yourself during a conversation and a collectivist mindset may be preferred when thinking about how to help the community.

When reflecting on learning about compassionate curiosity and practicing mindful communication by changing confrontational messages into polite questions/requests, many students noticed the positive effect of this strategy:

S3: I enjoyed learning about how I can change my words to reflect compassionate curiosity and I can still achieve my desired outcome without raising any conflicts. These skills of communication [...] are really helpful and will always be in my educational, professional, and social life.

S26: I feel like I’ll be a better person moving forward. It is always nice to discover new ways in which one can be effective, yet perfectly polite when communicating. For example, practicing compassionate curiosity was a huge eye-opener.

S30: I really enjoyed the compassionate curiosity practice [...]. This is because I say some of these statements and I didn’t know that it was more confrontational (assertive) than I thought it was. Getting to practice how to say things in a more compassionate way made me feel as if I can continue to do that with any interactions and not just in a conflict.

Based on the students’ feedback, the most valuable assignment that raised their self-awareness was the Conflict Style Assessment. They also learned a lot from the activities on individualistic/collectivistic conflict lenses, practicing compassionate curiosity, and learning to intervene.

5.2.3. Students’ Feedback on the Applicability of the Training Module

The third feedback question elicited how the training module on “Exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts” relates to the real world where the students live. In their comments, the students recognized that although conflicts are inevitable, they can apply what they learned in the module to approach them in a more confident, appropriate, and positive way:

S2: I felt that this module was one that will be extremely beneficial in the real world. Conflict is inevitable in the real world, so understanding how we best handle it is very important. It is also important to understand how I tend to approach conflict, as I can then work on aspects of conflict that I may be weaker at and aim to improve them.

S19: In the real world, fostering diversity, inclusion, and mutual understanding across other groups requires an awareness of how to approach and overcome intercultural problems. I [acquired] the abilities and information required to successfully navigate and resolve conflicts in my personal and professional life [...] by learning about inclusive solutions to intercultural disputes.

S28: It related significantly. People are so different and naturally their attitudes and approaches to different problems differ greatly. This module brings light to the various tools and approaches that exist that can help us navigate confrontations in an efficient and positive way.

In particular, the students stressed the applicability of what they learned in class to current conflicts that they experience in their university and work environments:

S15: I can apply this module via how I handle disagreements with people I care about, which is currently something that I deal with often.

S26: [This] is a very relatable module, because a lot of its content (compassionate curiosity, learning to intervene, etc.) show[s] up on a day-to-day basis, particularly in a school environment.

S33: Conflict between my partner and me is bound to arise, so learning more about how to use compassionate curiosity makes resolutions much easier.

The students demonstrated a deep understanding of cultural diversity and how mindfulness, empathy, and compassionate curiosity are critical in collaborating across differences and building a sustainable society.

S35: This module helps us with that so we will be more knowledgeable about behavioral and thought process differences across different cultures which we can apply to the real world to better connect with people.

S38: Empathy and engaging ambiguity are especially important in diverse settings like [our university]. You will eventually have to work with a classmate from a different culture or background, and being mindful of these differences and working towards common ground is very important.

S44: I think that mindfulness is very important to where I am. For me, the United States is a melting pot of different cultures. Being mindful of my physical and psychological decisions at all times is the best way to avoid conflict and collaborate with others.

To summarize, the excerpts from students’ self-reflective feedback provide strong evidence that the InterEqual training module on “Exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts”, combined with the completion of an intercultural telecollaboration project, has a strong potential to raise students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles. Moreover, the students reported that they felt that their communication skills improved and that they became better people and more effective intercultural communicators. Some of the students reported an immediate benefit from learning about how to deal with conflicts. Students also developed their skills to behave in a more proactive way by intervening when others were discriminated against or verbally attacked. Finally, they recognized the power of compassionate curiosity and empathy, and that those skills can be developed. Thus, the answer to RQ3—Does the combination of cooperative learning and critical self-reflection have the potential to raise students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles?—is yes. And, in addition to this, the study showed that this pedagogical approach contributes to the development of empathy, compassionate curiosity, and the ability to intervene to defend people who are discriminated against or attacked verbally.

6. Discussion of Limitations and Implications

This article summarized the insights from the analysis of data collected from MSI students who completed the InterEqual training module on conflict resolution combined with participation in an intercultural telecollaboration project. The main limitations of this study originate from the size of the sample and the fact that the data were collected within the same institution. Additionally, the data collection was conducted by applying self-report techniques and, therefore, may be subject to social desirability bias.

To sum up, the findings support the benefit of engaging students in a series of activities aimed at developing self-awareness of their conflict communication styles. The comparison of the pre- and post-project TEQ results showed an increase in the overall score of empathy. And the comparison of the pre- and post-project IRI assessments indicated that the proposed pedagogical intervention is likely to have a positive impact on students’ perspective-taking ability, which is so important for building sustainable societies in times of increasing polarization. Another important finding was that the majority of students who completed the training had a collaborative conflict style. Exploring if a student’s conflict communication style impacts their learning during the InterEqual modules will be important for future research.

Although the study findings cannot be generalized and future research is needed to establish a deeper understanding of the effect of the InterEqual pedagogical intervention on raising students’ self-awareness of their conflict communication styles and its impact on their empathy, the following research implications can be suggested:

First and foremost, universities should provide opportunities to all students, without exception, to develop their empathy and conflict-resolution skills by intentionally incorporating them into the curriculum. Learning to value diverse perspectives and navigate disagreements constructively will foster inclusiveness and intercultural dialogue.

Secondly, increasing students’ self-awareness should be at the core of developing these skills. Self-awareness helps students understand their emotions, behaviors, and how their words and actions impact others. Moreover, self-awareness, or a better understanding of oneself, is more likely to extend to understanding others.

Thirdly, intercultural telecollaboration projects should be considered as one of the possible pedagogical approaches, especially given the recent unprecedented situation during the COVID-19 pandemic, when opportunities for in-person communication were limited and whole higher-education systems moved online globally.

Next, the InterEqual training developed and piloted at an MSI in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States can be adopted as a good practice and adapted to a variety of local contexts.

Finally, a whole-institution approach is critical. In order to address the communication needs of a diverse campus community, such training should be offered not only to students but also to faculty and staff. In this way, the pedagogical intervention will contribute—to its full potential—to fostering diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice on campus and ultimately to creating a sustainable and inclusive campus culture.

Overall, I argue that initiatives such as the InterEqual training have strong potential to raise students’ self-awareness and empathy, help create a democratic public sphere, and thus contribute to advancing the humanistic agenda of higher education.

Funding

The development of the InterEqual training, including the module on “Exploring inclusive solutions to intercultural conflicts”, was funded by Hrabowski Innovation Fund. The student research assistance was co-funded by the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Student Research Assistance grant. And, the presentation of this study at the annual conference of the American Association for Applied Linguistics held in March 2023 in Portland, Oregon (USA), was funded by the UMBC Center for Social Science Scholarship Small Research Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project proposal was reviewed in accordance with the Institutional Review Board guidelines at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (protocol #1226, approved on July 18, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to the students who participated in this study, and to the graduate research assistants: Danielle Barefoot, Samantha Benton, and Shivam Gohel.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | This research study is not part of the Hrabowski Innovation Fund project on Enhancing Student Engagement in Internationalization at Home: Towards Inclusiveness and Intercultural Dialogue. |

| 2. | The experiential learning approach was put forward by David A. Kolb [25]. |

References

- Cai, D.; Fink, E. Conflict style differences between individualists and collectivists. Commun. Monogr. 2002, 69, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.A.; Guerrero, L.K. Managing conflict appropriately and effectively: An application of the competence model to Rahim’s organizational conflict styles. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2000, 11, 200–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.S. The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution: A Practitioner’s Guide; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, C.-H.; Louw, L. Managerial values in transcultural conflicts in South Africa. J. Intercult. Commun. 2012, 12, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A. Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2002, 13, 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubisky, P.; Ting-Toomey, S.; Lin, S.L. The influence of individualism-collectivism and self-monitoring on conflict styles. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1991, 15, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusser, B. Reconsidering higher education and the public good: The role of public spheres. In Governance and the Public Good; Tierney, W.G., Ed.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. Neoliberalism, corporate culture, and the promise of higher education: The university as a democratic public sphere. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2002, 72, 425–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R. The coming of the ecological university. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2011, 37, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M.; Golubeva, I. From intercultural communicative competence to intercultural citizenship: Preparing Young People for Citizenship in a Culturally Diverse Democratic World. In Intercultural Learning in Language Education and Beyond: Evolving Concepts, Perspectives, and Practices; McConachy, T., Golubeva, I., Wagner, M., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M.; Golubeva, I.; Porto, M. Internationalism, democracy, political education. In Global Citizenship in Foreign Language Education: Concepts, Practices, Connections; Lütge, C., Merse, T., Rauschert, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2023; pp. 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, I. Intercultural citizenship education in university settings. In Handbook of Civic Engagement and Education; Desjardins, R., Wiksten, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Golubeva, I.; Di Maria, D.; Holden, A.; Kohler, K.; Lee, J.; Wade, M.E. Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the Campus Climate and Intergroup Relations: Insights from a Campus-Wide Survey at a Minority Serving University; University of Maryland Baltimore County: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2023; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Golubeva, I.; Porto, M. Educating democratically and interculturally competent citizens: A virtual exchange between university students in Argentina and the USA. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2022, 10, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz-Deaton, C.; Golubeva, I. Intercultural Competence for College and University Students: A Global Guide for Employability and Social Change; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Education for citizenship in an era of global connection. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2002, 21, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, M.; Golubeva, I.; Byram, M. Channelling discomfort through the arts: A COVID-19 case study through an intercultural telecollaboration project. Lang. Teach. Res. 2023, 27, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. Neo-liberalism and marketisation: The implications for higher education. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Aşkun, D.; Çetin, F. The role of mindfulness in conflict communication styles according to individual locus of control orientations. J. Organ. Cult. Commun. Confl. 2016, 20, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.; Song, F. Emotions in the conflict process: An application of the cognitive appraisal model of emotions to conflict management. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2005, 16, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Van Knippenberg, D. The possessive self as a barrier to conflict resolution: Effects of mere ownership, process accountability, and self-concept clarity on competitive cognitions and behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, T.; Agllias, K. Student reflections on vulnerability and self-awareness in a social work skills course. Aust. Soc. Work 2019, 72, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carden, J.; Jones, R.J.; Passmore, J. Defining self-awareness in the context of adult development: A systematic literature review. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 46, 140–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin, M.J.; Roseth, C.J. Effects of cooperative learning on peer relations, empathy, and bullying in middle school. Aggress. Behav. 2019, 45, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntersdorfer, I.; Golubeva, I. Emotional intelligence and intercultural competence: Theoretical questions and pedagogical possibilities. Intercult. Commun. Educ. 2018, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R. Teaching Students to be Peacemakers, 4th ed.; Interaction Book Company: Edina, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. An overview of transformative learning. In Lifelong Learning: Concepts and Contexts; Sutherland, P., Crowther, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. Humanistic Education vs. Professional Education. J. Hum. Psychol. 1979, 19, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, T.J.; Kavookjian, J.; Ekong, G. Associations among student conflict management style and attitudes toward empathy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019, 11, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClam, T.; Diambra, J.F.; Burton, B.; Fuss, A.; Fudge, D.L. An analysis of a service-learning project: Students’ expectations, concerns, and reflections. J. Exp. Educ. 2008, 30, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, D.M. Cultivating self-awareness with team-teaching: Connections between classroom learning and experiential learning. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2013, 12, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, I.; Guntersdorfer, I. Addressing empathy in intercultural virtual exchange: A preliminary framework. In Virtual Exchange and 21st Century Teacher Education: Short Papers from the 2019 EVALUATE Conference; Hauck, M., Müller-Hartmann, A., Eds.; Research-publishing.net, 2020; pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreng, R.N.; McKinnon, M.C.; Mar, R.A.; Levine, B. The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. J. Personal. Assess. 2009, 91, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Kilmann, R.H. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument; Xicom: Tuxedo Park, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).