Food Insecurity Levels among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Enrolment

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Policy Brief: Food Security; FAO Agriculture and Development Economics Division: Rome, Italy, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, H.; Saikia, A.A. Food security: A review on its definition, levels and evolution. Asian J. Multidimens. Res. (AJMR) 2018, 7, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.A. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J. Nutr. 1990, 120, 1555–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, S.; Pencheon, D.; Bickler, G. The sustainable development goals provide an important framework for addressing dangerous climate change and achieving wider public health benefits. Public Health 2019, 174, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021: Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; Food & Agriculture Org.: Rome, Italy, 2021; Volume 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Direção Geral da Saúde. REACT-COVID—Inquérito Sobre Alimentação e Atividade Física em Contexto de Contenção Social; Direção Geral da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- El Zein, A.; Shelnutt, K.P.; Colby, S.; Vilaro, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Greene, G.; Olfert, M.D.; Riggsbee, K.; Morrell, J.S.; Mathews, A.E. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among US college students: A multi-institutional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancer, S.M.; Hunsberger, B.; Pratt, M.W.; Alisat, S. Cognitive complexity of expectations and adjustment to university in the first year. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, D.; Anderson, J.; Auld, G.; Champ, J. Good Grubbin’: Impact of a TV cooking show for college students living off campus. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, E.L.; Brown, M.; Karpinski, C. Prevalence of Food Insecurity in the General College Population and Student-Athletes: A Review of the Literature. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davitt, E.D.; Heer, M.M.; Winham, D.M.; Knoblauch, S.T.; Shelley, M.C. Effects of COVID-19 on university student food security. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBate, R.; Himmelgreen, D.; Gupton, J.; Heuer, J.N. Food insecurity, well-being, and academic success among college students: Implications for post COVID-19 pandemic programming. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, C.J.; Ellison, B.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Are estimates of food insecurity among college students accurate? Comparison of assessment protocols. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Insolera, N.; Cohen, A.J.; Wolfson, J.A. The Long-Term Effect of Food Insecurity during College on Future Food Insecurity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregório, M.J.; Graça, P.; Costa, A.; Nogueira, P.J. Time and regional perspectives of food insecurity during the economic crisis in Portugal, 2011–2013. Saúde Soc. 2014, 23, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.C.; Santos, A.B.; Camolas, J. O paradoxo insegurança alimentar e obesidade: Uma revisão da realidade portuguesa e dos mecanismos associados. Acta Port. Nutr. 2018, 13, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gregório, M.J.; Graça, P.; Santos, A.C.; Gomes, S.; Portugal, A.C.; Nogueira, P.J. Relatório INFOFAMÍLIA 2011–2014; Gomes, S., Ed.; Direção-Geral da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato, L. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física IAN-AF 2015–2016: Relatório de Resultados; Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.N.; Gregório, M.J.; Santos, R.; Marques, A.; Rodrigues, B.; Godinho, C.; Silva, C.S.; Mendes, R.; Graça, P.; Arriaga, M. Towards an In-Depth Understanding of Physical Activity and Eating Behaviours during COVID-19 Social Confinement: A Combined Approach from a Portuguese National Survey. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmi, A.; Martinez, S.; Byrd, A.; Robinson, D.; Bianco, S.; Maguire, J.; Crutchfield, R.M.; Condron, K.; Ritchie, L. A systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M.N. The struggle is real: A systematic review of food insecurity on postsecondary education campuses. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.; Morrell, J. Food insecurity prevalence among university students in New Hampshire. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Alves, E.; Marques, B.; Saraiva, C.; Azevedo, J. Carta para a alimentação saudável da Universidade de Tras-os-Montes e Alto Douro. In Campus y Ciudadanías Saludables: Estudios Para Una Promoción Integral de la Salud en la Región Iberoamericana; Universidad de Burgos: Burgos, Spain, 2020; pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Desa, U. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/11125 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Aguiar, A.; Maia, I.; Pinto, M.; Duarte, R. Food Insecurity in Portugal during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Prevalence and Associated Sociodemographic Characteristics. Port. J. Public Health 2022, 40, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregório, M.J.; Graça, P.; Nogueira, P.J.; Gomes, S.; Santos, C.A.; Boavida, J. Proposta Metodológica Para a Avaliação da Insegurança Alimentar em Portugal; Revista Nutrícias 21: 4-11; 2014; Available online: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/17617/1/proposta.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Gregório, M.; Nogueira, P.; Graça, P. The First Validation of the Household Food Insecurity Scale in a Sample of the Portuguese Population. Desigualdades Sociais No Acesso a Uma Alimentação Saudável: Um Estudo na População Portuguesa. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Nutrition and Food Sciences of University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Anthropometric reference data for International use: Recommendations from a WHO Expert Committee. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 64, 650–658. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Kurdian Maranha, L.; Sampaio, M.d.F.A.; Marín-León, L.; Panigassi, G. An adapted version of the US Department of Agriculture Food Insecurity module is a valid tool for assessing household food insecurity in Campinas, Brazil. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukegbu, P.; Nwofia, B.; Ndudiri, U.; Uwakwe, N.; Uwaegbute, A. Food insecurity and associated factors among university students. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.; Serebryanikova, I.; Donaldson, K.; Leveritt, M. Student food insecurity: The skeleton in the university closet. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 68, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldavini, J.; Andrew, H.; Berner, M. Characteristics associated with changes in food security status among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mialki, K.; House, L.A.; Mathews, A.E.; Shelnutt, K.P. COVID-19 and college students: Food security status before and after the onset of a pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.R.; Brito-Silva, F.; Kirkland, T.; Moore, C.E.; Davis, K.E.; Patterson, M.A.; Miketinas, D.C.; Tucker, W.J. Prevalence and social determinants of food insecurity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erasmus, G. Research on the Habits of Erasmus Students: Consumer, Daily Life, and Travel Habits of Erasmus Students from the Perspective of Their Environmental Attitudes and Beliefs; Green Erasmus Partnership: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; McFall, W.; Nord, M. Food Insecurity in Households with Children: Prevalence, Severity, and Household Characteristics, 2010–2011; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, I.; Monjardino, T.; Frias, B.; Canhão, H.; Cunha Branco, J.; Lucas, R.; Santos, A.C. Food Insecurity in Portugal Among Middle- and Older-Aged Adults at a Time of Economic Crisis Recovery: Prevalence and Determinants. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Shah, T.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, W.; Din, I.U.; Ilyas, A. Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Drammeh, W.; Hamid, N.A.; Rohana, A. Determinants of household food insecurity and its association with child malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the literature. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2019, 7, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Brennhofer, S.; Van Woerden, I.; Todd, M.; Laska, M. Factors related to the high rates of food insecurity among diverse, urban college freshmen. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Ramsey, R.; Ong, K.W. Food insecurity: Is it an issue among tertiary students? High. Educ. 2014, 67, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Van Woerden, I.; Todd, M.; Laska, M.N. Hungry to learn: The prevalence and effects of food insecurity on health behaviors and outcomes over time among a diverse sample of university freshmen. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.B. “Free food on campus!”: Using instructional technology to reduce university food waste and student food insecurity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 1959–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Patterson, A.J. Predictors of food insecurity among Australian university students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.A.; Carman, K.G. You can be too thin (but not too tall): Social desirability bias in self-reports of weight and height. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2017, 27, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Classification | Cutting Points | |

|---|---|---|

| With members under 18 years old | Without members under 18 years old | |

| Food Security | 0 | 0 |

| Mild FI | 1–5 | 1–3 |

| Moderate FI | 6–9 | 4–5 |

| Severe FI | 10–14 | 6–8 |

| Questions | n (%) |

|---|---|

| All students (n = 284) | |

| 1. In the past 3 months, have you ever felt worried that food in your household might run out before you had enough money to buy more? | 38 (13.4) |

| 2. In the last 3 months, did you run out of food before you had the money to buy more? | 9 (3.2) |

| 3. In the last 3 months, did your household members run out of money to have a healthy and varied diet? | 14 (4.9) |

| 4. In the last 3 months, did your household members have to eat the only food they still had at home because they ran out of money? | 20 (7.0) |

| 5. In the last 3 months, has any adult household member (aged 18 or over) missed a meal because they did not have enough money to buy food? | 6 (2.1) |

| 6. In the last 3 months, did any adult household member eat less than they thought they should because they did not have enough money to buy food? | 18 (6.3) |

| 7. In the last 3 months, has any adult member of the household felt hungry but not eaten due to not having had enough money to buy food? | 5 (1.8) |

| 8. In the last 3 months, has any adult member of the household gone a whole day without eating or had only one meal throughout the day because they did not have enough money to buy food? | 3 (1.1) |

| Students with household members under 18 years old (n = 194) | |

| 9. In the last 3 months, have the children/adolescents in your household (under 18 years of age) been unable to have a healthy and varied diet due to lack of money? | 1 (0.5) |

| 10. In the last 3 months, did the children/adolescents in your household have to consume food that they still had at home because they had run out of money? | 1 (0.5) |

| 11. In the last 3 months, in general, did any child/adolescent in your household eat less than they should have because there was no money to buy food? | 1 (0.5) |

| 12. In the last 3 months, was the amount of food in the meals of any child/adolescent in your household reduced because there was not enough money to buy food? | 2 (1.0) |

| 13. In the last 3 months, has any child/adolescent in your household skipped a meal because there was not enough money to buy food? | 0 (0.0) |

| 14. In the last 3 months, have any children/adolescents in your household felt hungry but not eaten due to not having enough money to buy food? | 0 (0.0) |

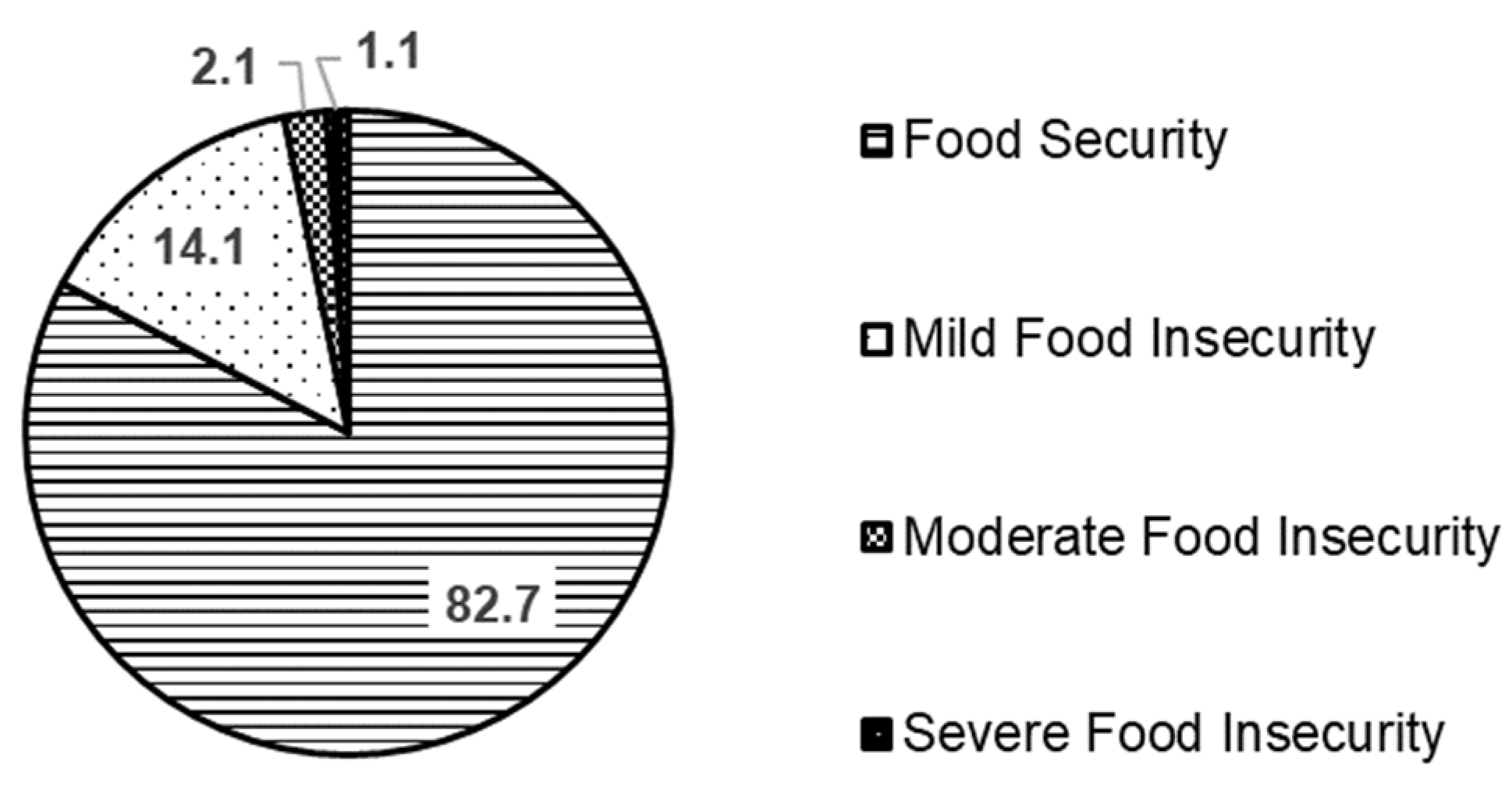

| Total n = 284 | FS n = 235 (82.7%) | FI n = 49 (17.3%) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| ≤18 years | 50 (17.6) | 44 (88.0) | 6 (12.0) | 0.279 |

| >18 years | 234 (82.4) | 191 (81.6) | 43 (18.4) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 228 (80.3) | 188 (82.5) | 40 (17.5) | 0.794 |

| Male | 56 (19.7) | 47 (83.9) | 9 (16.1) | |

| Body Mass Index | ||||

| Underweight | 17 (6.0) | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | 0.402 |

| Normal weight | 220 (77.5) | 181 (82.3) | 39 (17.7) | |

| Overweight | 33 (11.6) | 28 (84.8) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Obesity | 14 (4.9) | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | |

| Education level | ||||

| Bachelor | 218 (76.8) | 183 (83.9) | 35 (16.1) | 0.097 |

| Master | 56 (19.7) | 42 (75.0) | 14 (25.0) | |

| PhD | 10 (3.5) | 10 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 24 (8.5) | 216 (83.1) | 44 (16.9) | 0.628 |

| Unemployed | 260 (91.5) | 19 (79.2) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Residence region | ||||

| Norte | 258 (90.8.) | 212 (82.2) | 46 (17.8) | 0.787 |

| Centro | 13 (4.6) | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Lisboa e Vale do Tejo | 4 (1.4) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Alentejo | 1 (0.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Madeira | 4 (1.4) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Açores | 1 (0.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 3 (1.1) | |||

| Nationality | ||||

| Portuguese | 275 (96.8) | 230 (83.6) | 45 (16.4) | 0.028* |

| Other | 9 (3.2) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Number of household members | ||||

| ≤2 | 46 (16.2) | 32 (69.6) | 14 (30.4) | 0.058 |

| 3 | 85 (29.9) | 75 (88.2) | 10 (11.8) | |

| 4 | 122 (43.0) | 102 (83.6) | 20 (16.4) | |

| ≥5 | 31 (10.9) | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | |

| Number of household members ≥65 years old | ||||

| <1 | 253 (89.1) | 210 (83.0) | 43 (17.0) | 0.743 |

| ≥1 | 31 (10.9) | 25 (80.6) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Number of unemployed household members | ||||

| 0 | 210 (73.9) | 184 (87.6) | 26 (12.4) | 0.001* |

| 1 | 56 (19.7) | 40 (71.4) | 16 (28.6) | |

| ≥2 | 18 (6.3) | 11 (61.1) | 7 (38.9) | |

| Number of household members contributing to family income | ||||

| ≤2 | 258 (90.8) | 216 (83.7) | 42 (16.3) | 0.171 |

| >2 | 26 (9.2) | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) | |

| Presence of household members that smoke everyday | ||||

| No | 194 (68.3) | 155 (82.9) | 32 (17.1) | 0.073 |

| Yes | 90 (31.7) | 79 (84.0) | 15 (16.0) | |

| Do not know | 3 (1.1) | |||

| Household members under 18 years old | ||||

| No | 90 (31.7) | 155 (79.9) | 39 (20.1) | 0.062 |

| Yes | 194 (68.3) | 80 (88.9) | 10 (11.1) | |

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher BMI a | 1.166 | 0.523–2.602 | 0.707 |

| Non-Portuguese nationality b | 4.089 | 1.057–15.821 | 0.041 * |

| Higher number of household members c | 2.537 | 1.231–5.230 | 0.012 * |

| Higher number of unemployed household members d | 3.192 | 1.681–6.059 | <0.001 * |

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| In the last 3 months, did your household members change their consumption of any food considered essential (e.g., fruit, vegetables, fish, meat, rice, potatoes, pasta) due to economic difficulties in purchasing it? | |

| Yes | 21 (7.4) |

| No | 263 (92.6) |

| In the last 3 months, what were the main dietary changes in your household due to economic difficulties? | |

| Eat out less | 63 (22.9) |

| Obtain food through own production or from family members or others | 25 (9.8) |

| Receive food or other outside help | 5 (1.8) |

| The following reasons show why people do not always eat enough. Indicate if any of them apply to you: | |

| Do not have enough money to buy food | 10 (3.5) |

| Lack of gas, electricity, or an electrical appliance | 3 (1.6) |

| Unable to cook or eat due to health problems | 10 (3.5) |

| Lack of time | 3 (1.6) |

| It is very difficult to have access to a food outlet | 3 (1.6) |

| The following reasons show why people do not always have the types of food they want or need. Indicate if any of them apply to you: | |

| Good quality food is not available | 20 (7.0) |

| The food desired is not available | 16 (5.6) |

| Do not have enough money to buy food | 20 (7.0) |

| It is very difficult to have access to a food outlet | 5 (1.8) |

| A healthier and varied diet turns out to be more expensive | 1 (0.39) |

| In the last 3 months, the purchase of “white label” foods: | |

| Increased | 58 (20.4) |

| Did not change | 199 (70.1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, B.; Azevedo, J.; Rodrigues, I.; Rainho, C.; Gonçalves, C. Food Insecurity Levels among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Societies 2022, 12, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060174

Marques B, Azevedo J, Rodrigues I, Rainho C, Gonçalves C. Food Insecurity Levels among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Societies. 2022; 12(6):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060174

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Bebiana, Jorge Azevedo, Isilda Rodrigues, Conceição Rainho, and Carla Gonçalves. 2022. "Food Insecurity Levels among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study" Societies 12, no. 6: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060174

APA StyleMarques, B., Azevedo, J., Rodrigues, I., Rainho, C., & Gonçalves, C. (2022). Food Insecurity Levels among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Societies, 12(6), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060174