1. Introduction

On 17 October 2007, an article in the local press announced the “falling under the bulldozer blade” of the artistic mosaic that decorated the exterior wall of the main hall of the former Machinery and Spare Parts Enterprise (IUPS) in Suceava, an industrial complex renamed ROMUPS. This fact increases the number of cities in Romania that turn the massive mosaics into rubble [

1]. Despite warnings from the secretary-general of the Ministry of Culture and Religious Affairs and the conservation proposal of the director of the Bukovina Museum Complex, Suceava City Hall approved the demolition in favor of an investor who promised to build a housing complex. To the open letter addressed to the Suceava authorities by 11 local personalities, the mayor of Suceava replied: “I do not comment culturally on the value of this work, as a symbol of a distinct era. Probably the nostalgic ones want to keep it. I have no such nostalgia” [

2]. The debatable connotation of this statement reflects the slogan “let’s break it with the past”, specific to the post-1990 iconoclasm and the strategies for erasing the communist past and relics. The decision of the mayor’s office can also be related to the context of urban administration, which involves land use, as well as the revitalization and expansion of housing infrastructure to improve economic efficiency and social welfare for the local community. In this dynamic, we should not be surprised by the idiosyncratic mixture of old practices and innovative models of a “new reality”.

The theme of the evolution and aspect of socialist cities was intensely exploited in Central and Eastern European historiography over the past two decades [

3,

4,

5,

6], although it appeared in the literature of the 1990s [

7,

8]. Studies and surveys investigate the changing societal framework and the effect of ideology on social conditions, focusing on specific issues such as decision-making, spatial planning and urban experiences [

9,

10]. In addition, the photographic documentaries ensure a record of images, reflecting the aesthetic value of socialist relics and proposing another meaning of monumental art creations in the urban space [

11,

12,

13]. Capitals such as Warsaw, Sofia, Budapest, and the big cities of the former communist bloc are usually privileged in approaching the rise and institutionalization of the relationship between politics/politics of urbanism and art in the 1960s–1980s. In contrast, cities that appear as “small” in the international context [

14] generate, at best, case studies on the broader histories of socialist planning, modernization, and beautification. Surprisingly, these case studies challenge the stereotypical views that obscured the historical effigies, presenting them as standardized socialist urban landscapes. It is not about cities created by the post-war industrialization, such as Nowa Huta in Poland, Dimitrovgrad in Bulgaria, Leninváros in Hungary, Most in Czechoslovakia, or Schwedt in East Germany, but the former medieval residences like Bielsko-Biała in Poland [

15] or Plovdiv in Bulgaria [

16]. The changes in the cultural policies during the communist period were predominantly normative, the state having an overwhelming role in the supervision and coordination of the artistic production. Socialist regimes sought to differentiate themselves from previous ones by material and visual forms (more imposed than recommended) and by the discourse on innovation and effectiveness of the urban composition and aesthetics accessible and meaningful to all citizens. The ideology that dictated the new orientation in the artistic conception of the built environment relied on economy, functions, and rationality [

17], taking the form of ”socialist realism” or ”national socialism”. Likewise, the interference of politics in the messages of art influenced the artist’s decision [

18] even if his condition (i.e., recognition of his usefulness to society, his ethical stature and the dilemma dimension of the profession regarding the treatment of freedom and coercion) remained active within the ”compromise area” [

19] or the ”space of professional conscience” [

17]. Regardless of the approach, the reflection on how the communist project intervened in the artistic dimension and the imprint of the urban space in general (not only of the big cities) opened possibilities to widen the range of research.

With regard to Romania, post-1989 literature on the transformation of cities has been produced primarily by architects and architectural historians, sociologists and, to a lesser extent, historians [

19,

20,

21]. Their interpretations oscillated between emphasizing and contextualizing local peculiarities within a broader history of urban avatars [

22,

23]. Not surprisingly, Bucharest, Cluj Napoca, and Iaşi have captured the interest of many researchers, the analysis highlighting the fragility of the planning system, either challenging or promoting spaces of historical significance and poor implementation of urban projects [

24,

25]. Other studies have focused on cities such as Braşov, Sibiu, and Hunedoara, showing how history, economics, and politics have interacted in the urban landscape [

19]. Similar to Hunedoara, which combined the emblem of its 15th-century Gothic castle with symbols of mass industrialization, Suceava added to its medieval citadel the hallmarks of socialist modernization [

26]. However, unlike Hunedoara, where the main economic interests left the cultural aspects in the background, Suceava was able to enrich its urban landscape with elements of socialist inspiration as well as models that activated the history and tradition of the region. Suceava also had a dimension that no one could ignore: its location in the ”heart” of a cultural area, with international resonance. Less than an hour’s drive away were the painted monasteries Voroneţ, Suceviţa, Moldoviţa, Arbore, and Humor (included, after 1990, on the UNESCO World Heritage List), which fascinated Romanian and foreign tourists with their exterior frescoes. In a duplicitous way, the local authorities enjoyed the fame of the mentioned religious places without forgetting to declare that the scenes that beautified their exterior walls (referring to God-Creator) belonged to the “history” or “old times” that had to be left behind. At the same time, the painted monasteries were located in the rural areas where the religious tradition could be explained as proof of the ancestral existence of the Romanian people. As opposed to the traditional village, the city of Suceava, as a county seat, had to prove the “renewal of the mind“ by beautifying the walls of its buildings following the Soviet theory of the “New Man“—creator of a just, equal, optimistic world. Nonetheless, the traditional folkloric symbols, which we might call “permissive-neutral“, were not removed effectively from the art projects, as long as many of the newcomers to the city, as a result of the industrialization of the area, still rooted their mentality in rural culture and civilization. The bizarre mixture of symbolically essentialized forms has become, to some extent, distinct from the murals in other cities of Romania, even if the artistic language was simple, perfectly transitive for the messages of power, and intelligible for the “popular masses“.

Undoubtedly, the history of Suceava during the communist period can be read in various ways. Still, there are not many monographs about Suceava or its urban evolution after Second World War. Except for the analysis of urban geography [

27], most of the works take the form of tourist guides, highlighting the glorious medieval period when it functioned as the capital of the Principality of Moldova [

28,

29,

30,

31]. There is also a lack of papers that focus on the value of urban heritage and, implicitly, the awareness of its conservation, with one exception, a study published in the early 1990s [

32]. In 2012, within the international project ATRIUM (Architecture of Totalitarian Regimes in Urban Management), the House of Culture of Suceava became a representative object for a comparative analysis of the architectural aspects of totalitarian regimes in the region of Southeast Europe [

33]. Unfortunately, it is one of the few works that go beyond the sphere of popularization, being endorsed by architects. No wonder the official non-inventoried heritage of Suceava has become a marginal issue in the mayor’s discussions, if not ignored in drawing up their urban modernization agendas. The result of this state of affairs is the very civic center of Suceava, increasingly grey and devoid of identity.

2. Theory and Methodology

Starting from the story of the demolition of the substantial industrial mural ornament of ROMUPS (a situation that would be complicated later by the compensations that the artist demanded from the mayor’s office), our article discusses the process of creating and evaluating exterior wall mosaics in Suceava, as material evidence of the communist past, but also as an aesthetic version of socialist art, more or less politicized. It aims to address one of the gaps in the historiography of Suceava by offering a perspective on the process of urban transformation during socialism and analyzing the relationship between the display of urban (re)development projects and that of “beautifying” the built space. As the constructions “frame and embody economic, social and cultural processes” [

34], Suceava can be also interesting for a historical retrospective, which captures the local specificity, indicating how to preserve the built heritage and avoid its intentional destruction.

The argument for our research originated in what Henri Lefebvre called “the space practice” [

35]. He stated that space is visible as a social product and that each form of society develops a specific vision for its specific and desirable evolution. Two dimensions characterize the “social production of space”: While the first reflects the daily, practical interaction of individuals with the place where they live and work, the second belongs to the “conceptualized” space generated by the compromise made to art by the political power. For Lefebvre, those who conceive space and represent it in plans, maps, projects or images reflect how power creates dominant discourses through the ways in which space is delimited, organized and controlled to meet particular purposes. Ideology is inseparable from practice, and it is the role of history to exemplify this relation: “We should have to study not only the history of space, but also the history of representations, along with that of their relationships- with each other, with practice, and with ideology. History would have to take in not only the genesis of these spaces but also, and especially, their interconnections, distortions, displacements, mutual interactions, and their links with the spatial practice of the particular society or mode of production under consideration” [

35]. In the communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, the ideological factor was not the only one that conditioned the social production of space, but it was decisive as long as the political actors decided to structure it [

36]. In their opinion, the aesthetic side was imperative only when “ennobling” the built environment, transmitting the general standards by those in power. The methodological approach of the article is also based on urban morphology, examining elements of the landscape and their transformation over time. The method aims to understand the processes of morphological change and to know the identity and actions of change agents, from institutions to individuals [

37].

A second aspect of the conceptual framework concerns “urban beautification”. In the communist states, “beauty” became the standard that should no longer be sought in nature, as it could be built politically and materially [

19,

38,

39]. The relationship between “beauty” and “function” has been debated since the 1950s due to industrialization and urban sprawl. The stakes rose in the next decade, as did the cultural-ideological imperative of spreading consensus and cohesion in the socialist state, which contributed to the “beautification of life.” The multifaceted presence of beauty ensured it a central place in the ideological matrix. However, it should not be limited to pure, sensory sensation, as in Western theories of beauty. The aesthetics of the socialist state were conceived as a combination of artistic beauty and political function and not as a pure feeling of pleasure or visual perception. In the rhetoric of the communists, the working people deserved a beautiful daily life, and this goal led to the need to beautify the cities. One of the privileged artistic genres was the monumental mural creation meant to decorate the public institutions of culture and education, then the residential spaces or factories. The new concept of “ornamenting” or “decorating” with mosaics or ceramic tiles allowed architects and artists to experiment, combining the object sign and the exterior design with the urban architecture.

The juxtaposition of the two major themes—Lefebvre’s “social production of space” and the “urban beautification” helps to understand the bond between the environment, dominant ideology and political practices. Space and history are in a continuous and reciprocal dialogue; therefore, one of the historian’s tasks is to recognize the message of those plastic signs articulated aesthetically and ideologically in their evolution and relation to the political or social actors.

Despite a generous, theoretical, and methodological framework fueled by the research results in anthropology, urban geography, sociology and heritage studies, the design of information on a historical background remains conditioned by the identification and access to historical sources. While urban reconfiguration and institutional organization can be more easily documented, with some documents even helping to decipher decision-making mechanisms, it is much more demanding to capture the perception of change of Suceava, which is invisible rather than opaque. This paper does not necessarily highlight the responsibility of the actors who transformed the historic city of Suceava but explores the historical context and the motivation of “beautifying” and “ennobling” the buildings by using mosaics loaded with ideological, humanistic, and secular rhetoric of the regime.

Based on written and visual sources (press, reports, addresses, and administrative correspondence, travel guides, sketches, photographs and postcards), we can outline our research itinerary by asking the following: How did the local authorities consider urban planning and how was “the beautification” of the space conceptualized? How were the new constructions approached concerning the general and national objectives of industrialization, urbanization and culturalization? How did local officials articulate their agenda, and how much did they extend the reconsideration of cultural and historical traditions to urban beautification plans? How were monumental works of art approached and evaluated after 1990, and what is their current status?

3. Argumentation and Discussion

The post-1990 revival of interest in the structures of the urban space and its symbolic narratives did not manage to make Suceava attractive enough for an exhaustive monograph, keeping its medieval Citadel as the most representative indicator of a glorious era. Many explanations on the town’s achievements refer to the former capital of Moldova and the residence of Stephen the Great (1457–1504), a representative political leader of the Eastern Middle Ages, also called “The Athlete of Christ” by Pope Sixtus IV due to his anti-Ottoman campaigns. From a “Moldavian perspective”, the narrative focuses on the 15th and 16th centuries, when the functional zoning generated by the Royal Court was “socially produced or embodied in increasingly large spaces for trade and crafts. The relocation of the capital of Moldova to Iaşi contributed to the city’s decline, with frequent wars and periods of occupation affecting many of the buildings. Towards the end of the 18th century, Suceava still had 25 churches decorated with murals (of Gothic origin, coming from the Transylvanian or Polish chain), almost 500 houses specific to medieval commercial townlets, slums, streets paved with beams (Armenian Lane/Uliţa Armenească) or stone (Boyars Lane/Uliţa Boierească) and a large square “of gathering and festivities” [

32].

Under the Habsburg rule, since 1774, at a time when the enlightened absolutism promoted by Maria Theresa and especially by Joseph II had raised mercantilism to the rank of state policy, Suceava benefited from the construction of buildings necessary for new institutions or nobles attracted by the political, economic and social conditions. However, until the middle of the nineteenth century, its urban appearance was not in line with the status received, that of “commercial city”, with its magistracy and the privilege of organizing an “annual fair”. Its urban profile was generally low, with an absolute predominance of single story houses. Even in its center, the fear of building in height was a consequence of the use of less resistant materials such as wood. Contact with Western architecture in the 1800s led to a change in the classical understanding of the architectural tradition. In 1856, the local authorities demanded the inclusion of Suceava “among the other cities in the monarchy” to overcome its “outdated” urban appearance [

31]. After the elaboration of the systematization of the cities of Bukovina, in 1874, in the central commercial area of Suceava houses were made of brick or stone, covered with tile or tin, provided with balconies and windows facing the street, and with aligned facades. Dominated by church towers, the urban profile was enriched by new and imposing buildings, according to their functions: schools, administrative offices, banking, cultural, or commercial establishments.

Until the 1930s, Suceava offered the viewer a landscape created by the play of roofs, with a unique charm given by the architectural variation of the facades (eclectic modernity, with shades of Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo and Classicism) or the decorative fantasy of the consoles and hardware of the balconies. The development of a new style and another urban composition added different elements to the physiognomy of Suceava, but it broke, somewhat, the stylistic unity of the traditional medieval past. However, the relative economic stagnation of the town in the interwar period and the phenomenon of “demographic weakening” [

32] contributed to the architectural heritage preservation.

The situation would change dramatically after World War II, with the city’s reconstruction plans following the principle of “rebuilding on new foundations” [

40]. For the local authorities, the most “acceptable” way of modernization was to clear the land by demolition and construct a new city, which would keep, isolated, some of the monumental buildings of the past. The administrative-territorial reorganization and transformation of Suceava into a “county residence” fueled the tendency to assert the urban prestige of a socialist nature. In 1957, the construction of blocks of flats began in the city. By 1960, more than 270 apartments had been completed, either in the historic center or at the periphery [

32]. In 1963, the opening of two plants (“Pulp and Paper” and “Wood processing”) generated a migration of labor from the villages to Suceava, explaining, on the one hand, the population growth and, on the other hand, the need to expand the urban territory (including the almost complete decommissioning of the St. Ilie village), the creation of new neighborhoods and, of course, the acceleration of the pace of construction. In 1956, the population of Suceava was 20,946 and in 1985 it reached 98,426 [

32]. Although some researchers believe that the rate of population growth has been faster than the expansion of the city, especially in terms of land for auxiliary units [

41], we can not ignore the creation, in about ten years, of five new neighborhoods in the south-western part of town. In only five years, according to the systematization sketches from 1975 and 1980, the remodeling and later demolition of the old urban center of the city raised the value of the urbanization indicator (by building new blocks) to over 90%, placing Suceava among the leading cities in the Moldova region [

32].

3.1. Beautifying the “New Citadel”

Urban beautification means, most of the time, the creation of an environment that is pleasant from an aesthetic point of view [

19]. It can take various forms, from urban renewal and functionality to artistic and ideological expression. For example, the interwar Suceava seen through the eyes of Simionescu was idyllic, typical of Bukovina fairs, and archaic in the picturesque “knot formed by dense shops” of Armenian or Moldovan houses; some of them were “more modernised”, while others, still “covered with shingles”, sprang from “bushy trees or flower gardens” [

42].

From the perspective of the resident of Suceava in 1965, a contributor to the regional daily “Zori Noi” (New Dawns), the city was gloomily described: “What seemed to be urban here was just a rural attribute pushed to some limits that expressed nothing but an insatiable pursuit of money. The fagged booths and the stalls with the shrewd merchants often lined up tirelessly along poor streets over which leaned countless balconies where, along with the drying clothes, the bored townspeople ate seeds, spitting out their shells, with indifference, on the muddy sidewalks”. Only the Citadel remained unchanged, “the town, scattered on the same streets” living in its shadow. The blame for this deplorable image belonged to the bourgeoisie who “had managed to push Suceava to the last stage of ruin”. That is why the fundamental problem of urbanization was the annulment or reconfiguration of elements reminiscent of the pre-war “bourgeois” period. The one who could do this was the “architect” defined, in the language of the 1960s, as an “exponent of beauty”, that is, the one who “let his imagination unfold according to the love and passion of thousands of the city’s inhabitants” [

43]. In other words, according to the theory of “social production of space”, art had to be brought into real space, accessible to all inhabitants, and artists were to take an active role in the construction of socialism by “beautifying” the public space. From the Marxist ideological perspective, the urban transformation was, at the same time, the stake and the means for breaking the past.

The whole architectural movement of Suceava followed two directions clearly outlined: on the one hand, modernism in its scholastic form, located between figurative and abstraction, and on the other hand, experimentalism in neo-traditionalist and neo-folklorizing version [

44]. Urban “beautification” in 1965–1975 expressed the tendency to affirm the concept of the new regime, including the architecture of residential blocks and public buildings. In socialist folklore, Suceava did not have only a “Medieval Citadel”; it had itself become a “New Citadel”, as one local poet wrote: “Green leaf, princely apple/At Suceava when I look/I seem to be getting younger/It’s so rejuvenated/My old Suceava/Also with big blocks/Charming princes, healthy and strong/peony sprinkled with dew/Suceava is a new citadel” [

45].

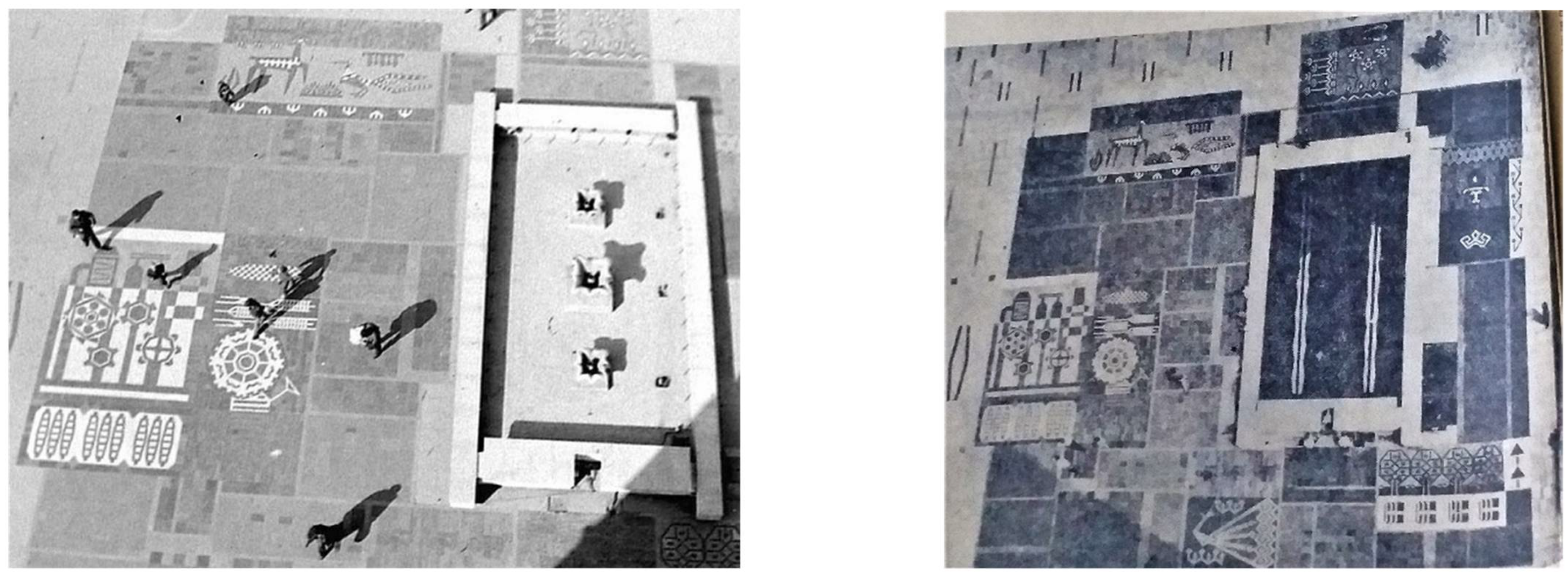

Paradoxically, while erasing the physical traces of the old houses, modernist architects claimed to have incorporated a particular spirit of the place into their projects. For example, the arrangement and decoration of the Central Square (Republic Square or 23 August Square), in 1964, solved a “space problem”: an open plateau to the Citadel, a large volume (10-storey tower block) in its south-western part, and a few smaller ones (4-storey blocks) arranged on its northern and southern side. On the one hand, the square organization was a typical example of modernist urban design by completely removing the more or less attractive 19th-century buildings. On the other hand, the architects considered the local specificity, suggesting an interpretation of the city landscape by arranging the built structures. In fact, since the mid-1960s, the authorities of Suceava have shown their openness to diversify the way the city was beautified by installing pavements with neutral, concentric layouts in regular or freely disposed spots. As a novelty, in the case of Central Square, it was precisely the pedestrian mosaic “with scenes from the history of the city and of Moldova and from our new life” (

Figure 1).

The propagandists defined the pavement large marble slabs as “a prestigious stamp on the surface of a city, introducing it into the circuit of urban values” and as “a transfiguration (in the highest way of art) of two histories brought together, by the people of Suceava, on the stage of a new and round fulfilment” [

46]. The mosaic contained stylized graphic elements (crown, mountain, river, peacock, deer, spike, gears) that referred to the relief, hydrography, fauna and flora of the area, the medieval history of the city, but also what was called “its new economic geography” [

28], “the beautiful every day”, and “the permanence of the anthological pages of the socialist construction in the northern part of the country” [

43].

3.2. The Outdoor Wall Mosaics of Suceava

The exaltation that emerges from the texts of the years 1960–1980 (local press, tourist guides, speeches at cultural events) reveals the issue of beautifying the architectural aspect of Suceava: the aesthetic-ideological combination. Trying to increase the artistic expressiveness of some blocks of flats in the newly built residential zone, the communist practices aimed at incorporating creative compositions into the architecture of the facades. Varied in size and texture, the facades had to carry the message (more or less ideologically charged) of the socialist transformation of society. The Decision of the Council of Ministers no. 1003 of 23 December 1963, provided, for “the stimulation of creativity in the field of fine arts and its closer connection to the requirements of socialist construction”, the role of control and guidance reverting to the State Committee for Culture and Art [

47]. One year later, the large-scale works of contemporary art (executed only by “living artists”) could be purchased by “public and cooperative organizations”, implicitly by the local administration. The general tendency to introduce the new socialist aesthetic in the urban environment became evident after 1964. All artistic projects for decorating the buildings had to ask for approval from the “Center” in Bucharest. Of all the types of monumental art, mosaic has become the most common and sustainable way to beautify the facades.

As everywhere in Romania, the artists experimented in Suceava with techniques and materials, making monumental tiles from small, natural stone and ceramics. According to the classifications of the composition—(a) folklore and national motives, (b) history and ideology, (c) work and industrialization, (d) sports and leisure—most artistic ensembles in Suceava belong to the first two categories. Analyzing the character or destination of the buildings on which the parietal mosaics were installed, with strict reference to the most representative ones, from 1966–1983, we propose another classification, as follows:

3.2.1. The Mosaics on the Facades of Apartment Buildings

In the mid-1960s, the director of the Department of Systematization, Architecture and Construction Design in Suceava underlined the importance of local peculiarities, asking the employees to reflect, in their design work, the rich folklore of the region and the artistic traditions. Unfortunately—he noted—“the large volume of construction in our region needed to be healed of the disease of pattern making”; otherwise, they would have appeared in localities “shot at the scapyrograph”, and their appearance might have seemed, “later, monotonous, tasteless” [

48]. Most of the photos in the local newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s illustrated new or under-construction blocks with unpainted or freshly painted walls. To avoid the monotony, but also to beautify the “new fortress” of Suceava, the members of the People’s Council of the Suceava Region asked the State Committee for Culture and Art, respectively the Fine Arts Council for approval to start the decoration of the balconies [

46] or the facades of some blocks. The themes that the small tiles were to illustrate were “the life of the youth”, “the wood exploitation and processing industry”, and the crafting of the region (fabrics, black pottery, Kuty ceramic). Financial reasons or re-prioritization prevented the realization of many projects. However, a few mosaics applied on plaster (alternating colors or non-figurative compositions) managed to cover some of the “high visibility buildings” positioned “on the traffic arteries” or “in the animated points of the city” [

49].

During the same period, following the systematization sketch from 1960, the urban plan focused on building cheap and good quality housing in the marginal areas of the city, often stigmatized as slums. The adoption of modernist elements quickly contributed to the composition of success stories published in the local press, in groups entitled “Notes” or “From the Reporter’s Notebook”. The articles—loaded with a visible communist credo—explained how to “put order” at the “western gate of the city”, where the landscape was most desolate: “At the bottom were the dark walls of the prison dating back to the time of Maria Theresa. Next to it—the field full of mud and corn stalks, as in Bacovia’s fair. All around, the look-alike small dwellings, a few dirty huts, a few sordid taverns lined up on both sides of the streets”. In a short time, the Arini neighborhood (located at the entrance to Suceava, from the West) was to reach the “pride of the city”, making locals and visitors “vibrate sincerely at the striking contrast between the bitter past and the uplifting present” [

43].

The blocks built between 1964 and 1965 were to be “painted in the spirit of our folk art, dividing the facades into various fields that will be colored differently, which is in the spirit of the mural painting from Voroneţ” [

50]. Such a discourse sought ideological legitimacy in taking over the traditional motifs and local-historical patterns that were to decorate the buildings in the “slum” that had become the center of interest for the intervention of local party authorities. At their suggestion, a group of 5 artists were hired (Virgil Almășanu, Dona Num, Mihai Velea, Constantin Crăciun and Istvan Vigh). The practice of the time required the commissioning of monumental works directly at the Union of Visual Artists in Bucharest. The art projects were assigned to the artists by the bureaucracy at the Centre or won by competition. Not infrequently, subjectivism and corruption interfered with the aesthetic quality of artistic creation in the absence of a transparent cultural policy that would guarantee the best-funded and the most ideologically controlled type of art [

51]. Led by Gheorghe Popescu from the University of Fine Arts in Bucharest, Romania these “monumentalist painters” had to visualize, on 700 m

2, a unitary decorative work sequenced in four compositions with allegorical narrative symbolism. Although fresco may have been an option, the governing bodies preferred mosaics. They were to create, “at the entrance to the city, a discreet specific atmosphere, a diffuse suggestion of the forests and people of Bukovina, their ancient customs and art or the general, essential elements of nature and art, in this part of the country” [

52]. The invoked “spirit of mural paintings from Voroneț” had nothing to do with religious symbolism but with the cultural complex of the periphery and the quality of strategies for asserting zonal and local identity. Typical of folkloric expressionism, the new iconography followed the desecrated conception of the world, which placed man in the center of attention as a supporter of creation.

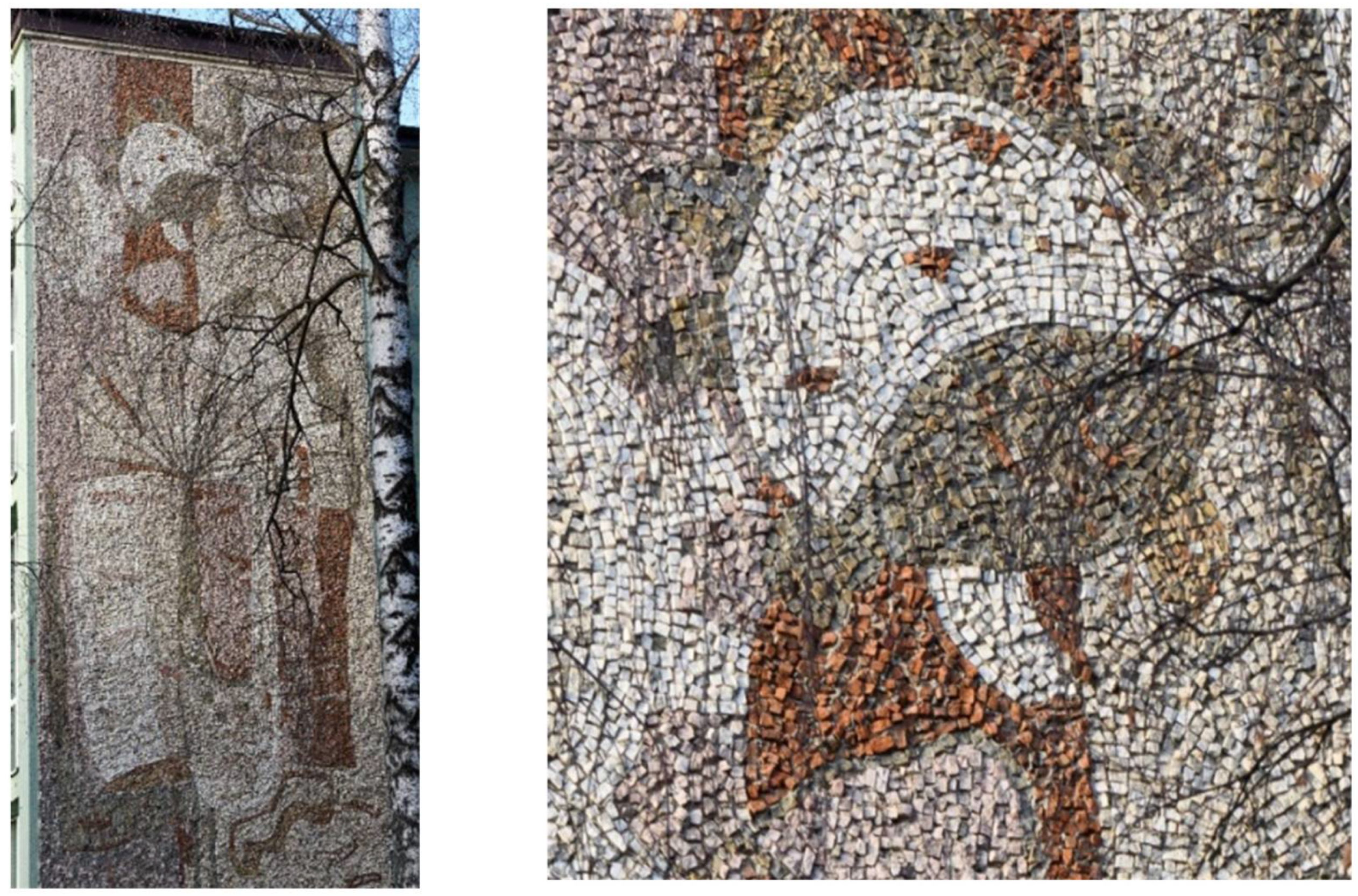

The three blocks of four-story buildings (the so-called “H-blocks”), arranged parallel to the main road of the city (or “Highway”), were tiled with mosaics meaning, in order, “Wedding” (14.80 × 5.25 m), “Forest” or according to other sources “Spring” (14.20 × 5.20 m), and “Hunting” (14.85 × 5.10 m). The drawing, in red and black, only “alluded” to a wedding, a hunt, or a forest, which must be “more felt than recognised” (

Figure 2). Human silhouettes (male and female depicted as equestrians, horn-hunters, archers, dancers), birds, deer, insects, trees (deciduous and coniferous) and folk motifs stylized the most striking features of the historic area was part of Suceava and frequently appeared on traditional fabrics.

On the ten-story tower block that dominated the square, the team of “monumental painters” installed a mosaic inspired by the essential myths of Romanian culture: “Mioriţa” and “Meşterul Manole”. We do not know the reason for the artists’ change of mind. Still, in the end, they gave up the theme of “Building Sacrifice” in favor of the pastoral epic, considered a symbol of the permanence of the Romanian people due to pastoralism as an ancient occupation. Large-scale (28.05 × 13.87 m), the work is arranged, as in the case of “H blocks”, in registers and strips illustrated with folk, vegetable motifs (Tree of Life, firs, flowers), zoomorphic (sheep, goats, birds), cosmogonic (sun, moon, stars) and geometric (spirals, circles), according to the “sobriety of our old song” (

Figure 3).

Surprisingly, the author of the article published in the regional daily “Zori Noi”, pointing out the value and significance of the new parietal mosaics, insisted on his description of the peculiarities of Bukovina. It was no longer a question of connecting the city to medieval Moldova, but to Bukovina, a province which had belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and which, after 1944, had been divided between the USSR (northern part, with Chernivtsi, the former duchy capital) and Romania (southern area, with Suceava, the medieval residence). According to this author, in the mosaics in Arini Square, one should not look for “a Bukovina of the postcards, with Romanian lads, sheep and hornbills, but an essentialised Upper Country, concentrated in a few lines, a discreet evocative creative atmosphere”. Also striking was the remark at the end of the text that referred to the mosaic of “glazed ceramic, yellow with spots, of monumental ugliness” (

Figure 4), placed on nearby buildings and which “forced the aesthetics of an important market” [

52].

The true intention of the builders and architects in choosing the yellow-black combination is also unknown; perhaps it was a random one, or it was a discreet expression of the choice of the two colors on the flag of the Austrian monarchy. Regardless of the scope of this choice, it was required to extract from the unfigured mosaics “unfortunate black dots” and replace them with others of a more appropriate color, or “a unitary colour, if not beautiful, at least bearable insight” [

52].

Seen through a permissive neutral, aestheticized and depoliticized artistic lens, the mural mosaics from the Arini/Areni section have passed the test of time thanks to their particularities of monumental artwork devoid of any overt doctrinal connotation. Neither before 1989 nor after 1990 did their symbolism offer the viewer a propagandistic interpretation, considering them more decorative, timeless and universally valid than ideologized. The risk of their destruction arose in 2010 when the residents raised the issue of thermal rehabilitation of their blocks. Without having the status of architectural heritage and legal protection provided by law, the mosaics of the H blocks remained only a landmark or symbol of the area, which gave identity to the neighborhood. The appeal of the Directorate for Culture and National Heritage Suceava highlighted the disinterest of the local authorities in classifying the monuments in the city and for the observance of the Law 120 of 2006. Trying to save the mosaics and prevent them from being dismantled or covered with polystyrene some architects proposed to install thermal insulation inside the apartments [

2].

3.2.2. The Mosaics on the Facades of Public Buildings (Education and Culture)

In June 1967, an address of the State Committee for Culture and Art mentioned the preference of Suceava’s authorities for ornamentation, blaming the local People’s Council for the lack of a firmer orientation towards works inspired by nature, and the specifics of the region, from the life of the working people or the historical and patriotic past of people. This type of creation, “which depicts what is most precious and specific to the region”, were “needed, to a greater extent, local, public and cultural institutions” [

49]. In fact, in the summer of 1967, there was a rather intense exchange of addresses and memoirs between the Council of Fine Arts in Bucharest, Romania and the local authorities of Suceava, one of the reasons being the mosaic on the outer wall of the Pedagogical Institute. The polychromatic marble mosaic, entitled “Education”, was an artistic stylization of the idea of promotion and enlightenment through education, having among its symbols the book, the bird, and the sun (

Figure 5).

The project of the painters Camilian Demetrescu and Vasile Varga had received approval in June 1966. Still, the bureaucratic delays led to the opening of the site only in October and the installation of the mosaic pieces in November. In a letter to the president of the Fine Arts Council, the two painters complained about the “more difficult” conditions in which they worked (“on blizzard and snow,” “at high altitude, on a makeshift scaffold and with ice in mortar”). Worse than that was the disinterest and malice of the beneficiaries—the People’s Local Council and the Pedagogical Institute—who had not supervised the action, but complained, at the end, of the unsatisfactory quality of the work such as the improper colors of the material, lack of perspective, and peeling stones. While these objections went unnoticed in Bucharest, the official interventions before the State Committee for Culture and Art and the Union of Visual Artists were successful, resulting in the “revision”, “remediation”, or “partial restoration” of the mosaic. Despite the tumultuous beginnings, the work lasted in the same place, on the walls of the building whose destination was later changed.

Much more contested than the “Education” mosaic were the ceramic tiles placed, in the same period, on the exterior walls of the stadium in Suceava. They were arranged according to “an immutable aesthetic criterion” or on every second part of the wall (reminiscent of a common saying: “a hard step and a soft one”), having a sports theme. A local journalist noticed that, shortly after the application, at least half of the plaques peeled off so that a large part of them had come to look “like after scarlet fever”. The appearance of the characters was “at least grotesque. (…) The striker has his left leg so prominent and, in many places, amputated by the weather. One of the two basketball players is, of course, an amateur. In fact, at least half of the immortalised athletes should be sanctioned by the referees, not having a regulatory attitude”. The work at the stadium contrasted with the “success of beauty”, which was the mosaic “Mioriţa” on the tower block in Arini. For this reason, the journalist concluded his material with the question: “What if, instead of a single colour, the plates contained, by analogy, housewives shaking carpets or making coffee?” [

53].

As for the mosaic on the side facade of the House of Culture—named later the Center of Culture and Socialist Creation “Song of Romania” of the Unions in Suceava—its history also had an interesting route. The building, constructed between 1965 and 1969 in the eastern part of the city’s Central Square, was to have one of the walls covered with a monumental fresco. A

Note from the Suceava archives shows that local propagandists and activists wanted all the artwork created for this edifice to evoke either Voroneţ (also called the “Sistine Chapel of the East“ due to the fresco of the “Last Judgment“ and its blue color) and the history of Moldova or the worker and industry. In a society rigid and suspicious of artistic symbols and meanings, the secretary of the Regional Committee of the Communist Party was unexpected rather than “balanced”: “Let’s not re-edit the frescoes from Voroneţ, nor should we force the note on contemporaneity, on the working element, because it would be annoying” [

49].

In an address sent, in July 1969, to the president of the Culture and Art Committee of Suceava County, the vice-president of the State Committee for Culture and Art indicated the painters who could make monumental works of art at the House of Culture in Suceava, as well as their projects’ titles. Thus, the team formed by Mihai Horea, Constantin Berdilă and Mircea Velea (authors of the work “Cântarea Ţării de Sus”/“The Song of the Upper Land”) and that of Constantin Crăciun and Paul Gherasim (who had proposed the mosaic “Luceafărul”/“The Evening Star” or “Mioriţa”) entered the competition. At the end of December 1971, some of the mentioned artists came to Suceava to present the black and white slides with images of two panels. As in the viewing and discussions participated the first secretary of Suceava County, “representatives of the working people, cadres from the county and municipality leadership, delegations of cultural institutions, DSAPC, artists”, some recommendations and clarifications were formulated: 1. The “Mioriţa” panel had to accentuate the region’s peculiarly about the human typology and the character’s clothing. The compositional details were subordinate to the theme’s deeply symbolic and humanistic revelation. 2. The second panel, on the side, presented the theme “Song of the Upper Land”. The recommendation was to give up the figure in the medallions, emphasizing the metaphorical and symbolic dimension of the oak in the center of the composition. The light was also to contribute to the symbol of the panel, going to the buttress of the building. The divergences related to the material of the monumental artwork (fresco or marble mosaic) led to the formation of a commission in Bucharest that was to establish, in February 1972, the most appropriate technique. Over the next several months, officials from Suceava agreed that only the “Song of the Upper Land” mosaic should adorn the House of Culture. The composition “Mioriţa” was to decorate the facade of the Cotton Spinning Mill from Gura Humorului (“located on the tourist route to Voroneţ”), and “Luceafărul” one of the “new constructions in the municipality” (without specifying which of them). None of the last two was made, in Gura Humorului appearing, in 1982, another mosaic entitled first “The national and economic specifics of Suceava County”, then “Bukovina Folk Traditions”, and, finally, “From the beauties of Bukovina”, designed and executed by the painters Napoleon Zamfir and Victor Feodorov [

49].

In 1973, the local authorities unveiled, on the side facade of the House of Culture of Unions in Suceava (

Figure 6), the parietal mosaic “The Song of the Upper Land” created by Constantin Crăciun, Constantin Berdilă, Paul Gherasim and Mihai Horea. With an area of 14.12 × 31.50 m and made of stone and marble, on a wall with a rugged surface, it has a non-figurative composition and reveals a discreet chromatic that appeals to faded tones (ochre, grey, yellow, brown, white, black). The plastic artists from Suceava understood its theme in a different range, insisting on “Phases of the Moon” (specific to the Midsummer/“Sânziene” Night, and the celebration of the town, on 24 June) or the “Oak” (as a symbol of endurance and permanence). There is no written evidence of the attitude of the locals towards “The Song of the Upper Land”, but some witnesses at the inauguration event remember that the mosaic delighted everyone [

54].

Unfortunately, even this mosaic did not enter the list to give it the status of an architectural heritage object, thus protecting it from vandalism. At the end of 2008, an unidentified person drew on the wall. Because the cleaning of the mosaic requires a dry surface, and the meteorological conditions prevented the rescue intervention [

55], the marks remained on the side facade of the House of Culture, altering its appearance already affected by the mercantile transformations of the last three decades.

3.2.3. The Mosaic on the Facade of the Machinery and Spare Parts Enterprise

Rapid industrialization changed the “face” of Suceava [

56], from the four enterprises (3 that produced food and one footwear) in the 1940s to a real industrial platform with pulp and paper mills, wood processing, metal constructions, machines and tools, car repairs, artificial fibers, and textiles. In 1969, according to the program of the Communist Party, which wanted to “provide the entire economy with technical equipment”, the Machinery and Spare Parts Industrial Enterprise was established in the “new citadel”. As a component of the machine-building industry, its purpose was to grant “in a significant proportion, the necessary utensils for the other branches, as well as an ever-increasing assortment of consumer goods” [

57]. Such a presence counted in the industrial landscape of Suceava, being part of a model of economic behavior that favors social development by hiring hundreds of workers from the city and adjacent localities. At the end of the 1970s, it was the responsibility of the local authorities to find suitable spaces for the execution of wall decorations of any kind, thus ennobling the buildings and promoting the monumental art [

49]. Not only blocks of flats, public edifices, and cultural institutions were of interest, but also factories and enterprises, which became “the decisive factor in reducing the gap with economically developed countries” [

58].

Unlike the period 1964–1970, both the documents of the local administration and the thematic orientation of the monumental works of art demonstrate an evident change of language. In a letter sent to Miu Dobrescu, a high-grade official from the Secretariat of the Communist Party, the chairman of the local Socialist Culture and Education Committee reminded of the need to “ennoble the facades of some industrial enterprises in Suceava County” and also to illustrate the “vast work of creating the new socialist society on these lands” [

49]. At the time of writing, the artists already had the projects in graphics and 1/1 size samples in the final material, which ensured efficiency in their realization. But beyond the “humanist” side of the factory’s artistic “ennobling”, there were some financial motivations that the local authorities did not ignore. The ping-pong game of correspondence between local and central political leaders shows that socialist art was not cheap at all. In the letter of 3 March 1980, the amount allocated by Bucharest for the execution of the mural mosaic was 1,629,004 lei, of which 366,000 went to the authors (an average annual salary in Romania was 2602 lei). The costs estimation sent by the Suceava Council in November 1980 was 8104 lei lower. A few weeks later, the representatives from Bucharest returned with a message approving the total amount of 1,629,005 lei [

49].

Less visually aggressive than the “state kitsch” exhibited by ideologically regimented art [

59], but with sufficient elements of propaganda, the mosaic was to enrich “the dowry of spiritual values existing in this part of the country”, bringing—as the local newspaper noted—“a vibrant homage to work” and “an ode to joys and socialist accomplishments”. Anchored “in the socialist present”, the artistic creation represented “The Man, in a multitude of metaphorical hypostases meant to give him both the force of action and the moral, soul dimension”. Moreover, the figurative preponderance, the gallery of faces and characters coming to illustrate the allegorical narrative proposed by the two artists. Other complementary elements (arches, coats of arms, inscriptions, trees, tulles, shields, stars, pigeons) made up the human and historical space (

Figure 7). A local journalist presented the mosaic as “an elegant business card about Suceava, today and forever”, illustrating the traditions and contemporary realities of the lands, without forgetting “the changes in the last decades in the life of the settlements” [

60].

The mosaic did not necessarily insist on the specific elements of the city or ethnographic area, such as those on the pavement of the Central Square, but on themes of universal value (peace, motherhood) or traditional Romanian specifics (horn players, characters dressed in popular costumes). After all, it “should not have just mirrored the occupations and ethnography of places, for art has, as it is known, its specific ways of reflecting the life and feelings of the soul”. Traian Brădean, one of the artists, did not explain his plastic vision either, limiting himself to stating that he intended to raise the level of creation “to the height of the demands of such an enterprise in an area with such a distinct personality in national culture and history” [

60]. Subsequently, during investigations generated by the removal and destruction of the mosaic in 2007, the journalists discovered its original title—“Songs for Man and Work”—and that was going to “ennoble” the metro station “Unirii Square” in Bucharest. As the costs of arranging the underground transport infrastructure were high, authorities decided to move the mosaic to Suceava, placing it on a visible wall [

1]. This explains why Brădean addressed, through the local newspaper, “sincere thanks to the county bodies, the relevant forums, to all those who showed understanding and gave us support” [

60]. Unlike the reception of “The Education” mosaic from the Pedagogical Institute (with appeals and dissatisfaction), on 13 October 1983, a commission composed of representatives of the Committee of Culture and Socialist Education of Suceava County found that the monumental art entitled “The heroism of the working class in the endeavour of socialist industrialisation”, covering an area of 456 m (6 m high and 76 m long), met the “artistic and thematic qualities according to the project”, being awarded as “very good” [

49].

More or less noticed by the workers or admired by the passers-by in the area, the mosaic wall from the Machinery and Spare Parts Enterprise has lasted 24 years. After 1990, the platform that concentrated the principal industrial units of Suceava changed its structure and character, becoming a “commercial area”. In addition, its location at the intersection of the three large administrative divisions of the municipality (Centre, Burdujeni and Itcani) attracted the attention of real estate developers. This state of art fueled the controversy between the opponents of the demolition of the mosaic (representatives of the intellectual, academic, cultural environment of Suceava) and the supporters of this action (the local and county administration). Although the Directorate for Culture, Cults and National Cultural Heritage had put it on the “consultative” list of public monuments in Suceava County, the mosaic was not under the protection of Law 120/2006 (regulating the legal framework for construction, location and administration of public monuments), nor was it included in the patrimonial records of the local administration. Notified in this regard, the prefect of Suceava—as a guarantor of compliance with the law and the government’s representative in the territory—justified the destruction of the mosaic since the owner had not raised any claim and the monumental work was not included in inventories of heritage objects. From his point of view, the mosaic was, however, anachronistic, “resembling the statue of Lenin in front of the Casa Scânteii/House of the Spark” [

1], referring to the removal, in Bucharest, of one of the most relevant symbols of loyalty to communist ideology referring to the removal, in Bucharest, of one of the most relevant symbols of loyalty to communist ideology. The mayor of Suceava also defined it, naming the signatories of an open letter proposing to save the mosaic as “crypto-communists”. Destroyed in the second half of October 2007, the monumental work became the subject of litigation between the authorities and the plastic artist Traian Brădean, the latter requesting one billion lei as compensation. Subsequently, neither the local media nor the City Council provided information on the status of moral damages due to the painter’s heirs, the subject of parietal mosaics that “beautified” or “ennobled” Suceava in the years of socialism faded into the background.

4. Conclusions

The complexity of the relationship between space-society-history and art-urban ideology leads us to believe that behind the visual representations that ordinary people read or intuit is not only what philosophers considered “cultural vision” but also a matter of displaying power. From this perspective, in the key proposed by Lefebvre, space is primarily political. In the form of buildings, monuments, statues or mosaics, some of the material evidence of the communist past in Romania (as everywhere in Central and Eastern Europe) is still in place. Many others were removed immediately after 1989 or abandoned until time turned them into ruins, helping the authorities to more easily justify the need for their demolition. After half a century dominated by the communist ideology and strategies of erasing authentic history, initiatives advocating the preservation and re-evaluation of socialist-type artistic creation have understood both the purpose of its nostalgic dimension and that of iconoclastic reasons and practices. From this perspective, demolition or conservation is no longer a purpose in itself (with some isolated exceptions) but a part of planning policies, integrated into a broad, conceptual, institutional, and legal framework.

In the case of Suceava—the capital of the medieval state of Moldova in its glory days and an ordinary, provincial city until the interwar period when it became the county seat—urban development projects were modelled at the intersection of local and central interests, negotiating its relevance depending on the context historically, the actors involved and the dynamics of power. Rather than an ideologically motivated struggle against a despised past (as evidenced by propaganda texts), the policy of expanding and then “beautifying” the built environment took advantage of the opportunities of a system that could be both rigid and porous. Thus, the Romanian version of socialist modernism did not ignore the traditional, local specificity, pondering the thematic constraint and offering the plastic artists a certain stylistic autonomy.

The mosaics of Suceava represent an integral part of the architectural image of a socialist city and also a material testimony of an era in which artists’ relationship with power passed through the restrictive framework of political and administrative institutions. Most of them belong to painters from Bucharest who maintained a high artistic level in the works commissioned by the communist authorities. Supporting the ideas of “beautification of the New Citadel” or “artistic ennobling of buildings”, they compromised the “practical utility of art” in their professional and material interest. Compared to many of the epics of socialism in stereotypical productions on buildings in other Romanian cities, the mosaics in Suceava are characterized by modernizing styles, illustrating abstract, floral, zoomorphic motifs, even inspired by traditional fabrics in the area. Not even the decoration of the House of Culture—a construction generally attributed to Soviet-origin cultural policies aimed at educating the masses following the principles of communist ideology—does not reflect, in Suceava, obedience to official iconography. The artistic style of the mosaics “Hunting/Vânătoarea”, “Mioriţa” or “The Song of the Upper Land/Cântarea Ţării de Sus” combined ethnography, symbolist techniques and scenes taken from Romanian mythology, bringing in line the ideal of autochthonism and aesthetics of 1965–1975 with that permissive neutrality that gave it quality even within the constraining system in power. “The heroism of the working class in the endeavour of socialist industrialisation”, destroyed in the “bulldozer era” due to its absence from the list of public monuments, did not enjoy the same appreciation. Seen as a product of a totalitarian epoch, the mosaic that “ennobled” the walls of an important factory in Suceava confirmed the paradox in which the local administration ignores the works of monumental art, and the locals pass over them. The lovers of socialist art lose the chance to see them in the most diverse and fascinating hypostasis.