Abstract

This paper uses the transition regime concept in a case study of how the regime in England has been reconstructed since the 1980s. It explains how the former transition regime evolved gradually up to the 1970s. Thereafter the regime proved unable to cope with an acceleration of de-industrialisation and the government’s switch to neo-liberal social and economic policies. These changes destroyed many working-class routes into employment. The resultant push onto academic routes, which had the attraction of continuing to lead to jobs, meant that the enlarged numbers exiting the routes could no longer rely on employment that offered secure middle-class futures. The paper explains how the next 30 years became a period of radical regime reconstruction. Government education, training and welfare policies and changes in the economy and occupational structure, were the context in which schools, colleges and higher education institutions, employers and other training providers, together with young people, ‘negotiated’ new routes from points to entry to exits into different classes of employment. At the beginning of the 2020s, the reconstructed regime was delivering the fastest education-to-work transitions in Europe, with lower than average rates of youth unemployment and NEET. Then came the challenges of COVID-19, lockdowns and Brexit.

1. Introduction

In the 1980s and 1990s, England drew attention from international youth researchers and policy-makers on account of its relatively extensive experience of addressing youth unemployment which had been an intractable problem in many regions of the UK from the mid-1970s. By the late 1980s youth unemployment was becoming an issue throughout Europe. Hence other countries’ interest in England’s relatively rich experience of trying to strengthen old and to build new bridges from education to work. By 2019 England had a different claim for international attention. It had lower rates of youth unemployment and NEET (not in employment, education or training) than most European countries, and was delivering the continent’s fastest education-to-work transitions. By age 19 a half of young people had started continuous full-time employment [1], and most of the remainder were doing so by age 24. The following passages explain how this turnaround has been achieved. It has involved a transformation of the transition regime.

Section 2 introduces the transition regime concept. Section 3 explains how England’s earlier regime was constructed from the 1870s onwards, and how this regime evolved during the 20th century. Section 4 describes how, from the 1970s and through the 1980s, the regime was broken by an acceleration of de-industrialisation and government neo-liberal social and economic policies. Section 5 is about the subsequent reconstruction of a 21st-century transition regime. The paper ends by noting how, during the 2020s, the reconstructed regime is being tested by the economic turbulence created by COVID-19 and lockdowns with further challenges ahead from Brexit and a cost-of-living crisis sparked by spiralling global energy prices.

2. Transition Regimes

Youth is essentially a transitional life stage. Individuals move from childhood origins, indicated here by family class and attainments in compulsory education, and eventually reach adult destinations, and here we focus on classes of employment. Young people make other journeys, in family relationships and housing for example, but here the focus is on transitions from education to work.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, youth transitions have lengthened in most countries [2]. The ages of completing full-time education and starting a first adult job have risen. Additionally, journeys have become more complicated, involving full- and part-time courses in post-compulsory education, part-time and temporary jobs, sometimes interspersed with spells of unemployment. One-step school-to-work transitions are now exceptional. New lengthened transitions are not necessarily linear. Young people may step backwards, from the labour market back into education, for example. This is the context in which researchers began to seek typical sequences of steps (career routes) that led from different childhood origins to different adult destinations.

During these recent decades of change, youth research has been internationalised, especially within Europe. Co-researchers from different countries have found themselves encountering educational institutions and qualifications not only with unfamiliar titles but playing roles in young people’s transitions with no direct counterparts in other researchers’ home countries. This was the context in which researchers began to conceptualise ‘transition regimes’ in which each part acquired significance only from its relationship with other parts of the regime (discussed fully in Roberts, 2020) [3]. Each step that a young person could take acquired value and significance from the typically preceding and subsequent positions. Different sequences of steps (career routes) derived their value and significance from the typical origins and employment destinations of contemporaries following adjacent career routes. This meant that a country’s transition regime had to be understood as a totality.

Cross-national research projects using qualitative methods with small samples of young people noted how the latter needed to mobilise resources, typically advice and information, from families and friends, teachers and career counsellors, in order to decide which next steps to take [4,5,6,7]. Informed decisions required knowledge of the country’s transition regime; at least those parts of the regime with which the young people were engaging.

As transitions lengthened and became more complex, most countries launched longitudinal research projects, surveying panels of young people at successive points during their education-to-work transitions [8,9,10,11]. The aim was to identify the main career routes that different groups of young people were taking. Cross-national projects soon found that details of career routes and groups were specific to particular countries and tried to develop typologies of transition regimes. The aim was to reduce a much larger number of countries to a small number of types then compare their performances, especially in minimising youth unemployment which had become a major problem in most of Europe Europe [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Suffice it to say that after a 25-year search, David Raffe (2008, 2014) [18,19] one of the pioneers in the quest, concluded that the search for a typology had failed and that it was impossible to identify any arrangements that would be best for all countries. He recommended that the transition regime concept should be used in single-country case studies, and this is the approach adopted here. This is not to say that typologies are devoid of value. They can focus attention on the similarities of the transition regimes in several countries. However, there is no single typology that can capture all the inter-country variations. Typologies need to be complemented by national case studies [20].

During the last 30 years, researchers handling longitudinal data sets containing information about young people’s positions at successive points in time have gained access to some powerful statistical methods including cluster and sequence analysis with which to identify career groups [21,22,23]. A problem with both cluster and sequence analysis is that outcomes always depend on the information that is input. Additionally, sequence analysis has difficulty in handling simultaneously different types of education and different types of employment that young people may occupy at the same chronological ages. The result is always a bewildering and incomprehensible number of sequences to which the standard response is to simplify into any kind of education and any kind of employment. Thus the basic descriptive value of these analyses is limited. Another limitation that applies equally to quantitative and qualitative data, cross-sectional and longitudinal, which is gathered solely from young people about their behaviour and positions, is that young people are just one of several sets of actors who construct career routes and groups.

Government education, training, employment and welfare policies set contexts in which lower and upper secondary and tertiary education institutions, employers and other training providers, pursue their own agendas, and young people select from the options that are available to them. Links between steps and boundaries between career routes are negotiated by the interactive agency of all these parties. The links between steps and boundaries between routes are not fixed but are constantly renegotiated in local education and labour markets, always within the constraints and opportunities offered by national government policies, which also change over time. History always matters. It is always the source of the present in which negotiations sustain some features of transition regimes while modifying others. Typologies have hitherto always been used to compare countries’ transition regimes at specific points in time. The outcome is an unrealistic static view of countries’ regimes. Typologies might also be used to highlight changes in a country’s regime, away from one type and towards another.

The following sections examine how England’s pre-1980s transition regime evolved from the late 19th century through changes in government policies and economic conditions and other actors’ responses to these changing contexts. We then see how economic restructuring followed by successive government policy initiatives, and negotiations within local education and employment markets in the late 1970s and 1980s failed to maintain routes that could be relied on to lead young people to types of employment that would sustain acceptable adult lives. The following three decades have been a period of radical regime reconstruction, not according to anyone’s masterplan but through governments, education and training providers, employers and young people negotiating new groupings at the entry to the transition regime, new employment class destinations, and new routes linking the two. At the beginning of the 2020s, the reconstruction could be considered successful with low rates of youth unemployment and economic inactivity compared with most European countries, though not to the all-round satisfaction of either England’s young people or employers.

3. Britain’s Transition Regime, 1870s–1970s

3.1. Entry

The pre-1980s regime had been built from foundations laid by the 1870 Education Act which enabled elementary schooling to be offered to all children, and attendance was made compulsory from 1880, initially from age 5 to 10 [24]. The school-leaving age was raised in stages as and when local provisions permitted to 12 or 13 and eventually to 14 throughout the country following the 1918 Education Act. These state-funded schools provided an ‘elementary’ schooling. The basic curriculum was the so-called 3Rs—reading, (w)riting and (a)rithmetic—supplemented by religious and physical education.

These schools were completely separate from those that offered secondary education, preceded by schooling in a preparatory department or a separate ‘prep school’. The schools had various titles—simply school, or college, or high school or grammar school but were unified by offering a secondary curriculum. This had originally been English, mathematics and classical languages to which modern subjects—science, modern languages, history and geography—were added during the 19th century. Some of the schools had originally been founded to educate children of the poor, and some still offered scholarship places, but access was usually by payment. Thus on entry to the transition regime, young people were divided into two groups: those with just elementary and those with secondary schooling. This divided education projected the master–servant, officer–men hierarchy into the industrial age.

The division remained intact when from 1902 local education authorities were permitted to purchase secondary school places for children from their elementary schools and to open secondary schools of their own which usually offered a combination of scholarship and paid-for places. These reforms created the so-called educational ladder up which children from modest backgrounds could rise [25]. Thus the idea of meritocracy was born: a new legitimation for a much older social order.

The division into two groups at the point of entry to the transition regime survived the 1944 Education Act which guaranteed secondary education for all, but usually in different types of secondary schools [26]. Former secondary schools became generically known as grammar schools. Most of the rest were called secondary moderns. Only grammar schools prepared pupils for the prestigious grammar school examinations and qualifications. The division into two groups on entering the transition regime survived the merger of grammar and secondary modern schools into comprehensives which began in the 1950s because pupils were divided internally into those taking the grammar school curriculum and examinations and the rest [27,28]. From the 1870s until the 1970s, those taking grammar school qualifications were a minority, albeit a slowly growing minority, and thus the division into master and servant classes survived raising the school-leaving age to 15 in 1947 and to 16 after 1972.

3.2. Destinations

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were just two main employment classes, clusters of occupations with similar characteristics, towards which school-leavers could head. There was the middle class whose normal work location was an office and a working class that performed physically more demanding work in factories, mines, transport, shipyards and docks. By the 1920s these industrial occupations had replaced domestic service which had formerly been the main source of employment for the working class [29,30].

By the 1970s the middle class had split. Office employment had expanded in large business corporations, public administration and services. Much of the more routine work had been mechanised, and operating typewriters, duplicating and accounting machines was deemed suitable work for young women who were expected to terminate their careers on marriage and parenthood [31], though throughout the post-1945 decades more were returning to work, usually part-time when their parental responsibilities made this possible. Males who were recruited into offices expected longer careers leading into management and the professions. Thus the ‘white-collar proletariat’ was mainly female [32]. Needless to say, this began to change as the Equal Pay Act of 1970 and the Equal Opportunities Act of 1975 were implemented. However, in the 1970s Goldthorpe and his colleagues (1987) [33] were able to identify lower-level non-manual employees as a distinct intermediate class, neither working class nor part of the ‘service class’ of managers and professionals.

The working class was always tiered, headed by an ‘aristocracy’ of skilled labour, nearly all male. Women in factories were typically engaged in lighter assembly work and packaging. Males’ jobs that were designated as unskilled because little training was required usually involved heavy ‘masculine’ manual labour.

The office and the works were linked by foremen, princes from the labour aristocracy, who liaised with junior managers, while professional engineers with their various specialities planned and maintained oversight of ‘the works’.

3.3. Career Routes and Groups

Up to 1939 two employment classes (middle and working) dovetailed neatly with an education system that separated young people into two types of schools. The division of the non-manuals into two employment classes, making three in total, made school-to-work transitions more complicated. It made six journeys possible, but only some of these were activated to become observable career routes along which career groups of young people travelled. Activation of possible routes always depends on the recruitment preferences of employers and the preferences of young people, in both cases within the options available to them. These preferences and choices may involve engaging with mediators who offer different types of post-compulsory education and vocational training. However, one-step school-to-employment transitions remained normal in Britain until the 1970s.

Grammar school education, and increasingly grammar school qualifications when these became available after the First World War, had normally been required for entry to any kind of non-manual employment. This applied even after an intermediate class of mainly feminised jobs was separated from management and professional occupations. Girls with grammar school qualifications, and some without, could ease their entry to ‘short careers’ in office work [34] by gaining touch typing and shorthand skills in further education. At age 16 boys could leave grammar schools and start in the office but usually expected, and were given, opportunities to train for and to be supported through further education that allowed them to ascend to management and professional positions. Grammar school boys could also start craft apprenticeships at age 16 but would then often be encouraged to use further education to gain qualifications that conferred professional status. This usually involved day release for college attendance granted by employers plus attending evening classes. Boys and girls who gained grammar school qualifications at age 16 could proceed to GCE A-levels, then into higher education. However, until the 1960s a university degree was absolutely essential only for aspirant medical doctors. Other professions could be entered gaining qualifications on further education’s ‘alternative route’. Ambitious girls were most likely to aim for careers as teachers or nurses. Boys trained to become solicitors, accountants and engineers.

During the 1960s professions that were able to do so started to become all-graduate at the point of entry, and businesses began to recruit university-educated management trainees. By the 1970s these trends were helping to separate the service class from intermediate occupations. However, until the 1980s the proportion of the workforce in management and professional jobs greatly exceeded the proportion of young people who progressed through higher education. In the late 1940s just 3 per cent of young people went to university and the percentage was only just reaching 15 per cent at the end of the 1970s. During this period the proportion of jobs that were in the service class rose from around 20 per cent to 30 per cent, and to 40 per cent by 1990, then stabilised. It was inevitable until the 1970s that most journeys into management and professional employment would be via the ‘alternative route’.

The choices on leaving school at 14, then 15, then 16 that were open to ‘the rest’ who did not have grammar school qualifications were more limited. Their options were usually limited to different types of working-class jobs. For girls this meant factory or shop. Boys who could offer some evidence of potential might obtain craft apprenticeships where short careers led to skilled working-class jobs [34]. Others started in unskilled or trained briefly for semi-skilled occupations. Girls could rise into office jobs by gaining office skills in further education.

Career routes following grammar school had always guaranteed smooth transitions into employment. Before 1939 ‘the rest’ faced barriers and ditches, especially when the economy slumped. This meant spells of unemployment and dead-end juvenile jobs from which individuals would be dismissed when aged 18–21 having grown ‘too old’ and eligible for adult wages. However, the full employment decades that followed the Second World War enabled the entire transition regime to deliver smooth transitions for all young people. It was employers who faced often intractable recruitment difficulties.

4. Breakdown

During the 1970s the transition regime that had evolved gradually over the previous century began to face challenges that the regime could not meet. In the 19th century, the regime had educated a minority for middle-class futures. The rest had been educated to become the so-called hewers of wood and drawers of water, albeit in industries rather than the homes of their betters. Up to 1902, the minority who received a secondary education was selected by parents’ ability and willingness to pay. The transition regime survived demands from the ‘hewers of wood’ for equal opportunities for their children. These demands were satisfied, at least temporarily, by state-funded scholarship places in secondary schools and selection of children for these places by tests of ability and aptitude, plus free higher education and means-tested maintenance grants for all who were offered university places. The transition regime survived occupational upgrading—the decline in the proportion of working-class jobs and increases at all non-manual levels, by boosting the numbers who could access grammar school qualifications, and the development of ‘alternative routes’ through further education.

4.1. De-Industrialisation

During the 1970s the regime began to suffer what would prove fatal wounds from an acceleration in the longer-term decline of employment, mostly working-class jobs, in manufacturing and extractive industries. The acceleration was due to competition from lower-cost countries, mainly in Asia, and also from other countries of the European Economic Community (now the European Union) which Britain joined in 1973. The other change driver was automation. Neither threat was new, but both strengthened in the 1970s and were amplified after 1979 when the UK government led Europe in adopting neo-liberal (originally called monetarist) social and economic policies. Forthwith markets were to set levels of employment in different business sectors.

Towns built around steel plants, shipyards, coal mines and manufacturing industries were stripped of their main sources of employment. Unemployment soared among young people who would formerly have embarked on working-class careers [35,36]. Britain was ahead of other European countries in this trend because, as the world’s first industrial nation, it had an abundance of old and vulnerable ‘smokestack’ industries. Thus Britain became Europe’s youth unemployment capital, and by the mid-1980s it was the country with a relative wealth of experience and experiments in addressing youth unemployment.

The first major initiative was the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) which ran from 1978 to 1983 and usually offered six months of work experience which was meant to strengthen young people’s positions when applying for [37,38]. YOP was eventually overwhelmed by the sheer volume of unemployment by which it was surrounded. Its replacement was the Youth Training Scheme (YTS), launched initially as a one-year scheme in 1983, relaunched as a two-year programme in 1986, and for a final time rebranded simply as Youth Training (YT) in 1990 [39,40]. There were accompanying initiatives: wage subsidies, measures to force down youth pay to a level at which unemployment would clear, a job release scheme which permitted early retirement on full pensions provided the vacated job was filled by an unemployed young person [41], efforts to make the secondary education of ‘the rest’ more vocationally relevant [42], assistance for young people to start their own businesses, and new employer-led vocational qualifications. Nothing worked! There was too much ‘churning’, temporarily ‘warehousing’ young people in training schemes, education programs and temporary jobs, which trashed the youth training ‘brand’. One of the first initiatives of the incoming government in 1997 was a ‘new deal’ for unemployed 18–25-year-olds. Youth unemployment had simply been pushed from 16 and 17-year-olds to the next higher age bands. This new deal was another policy failure! Some young people’s careers recovered during the 1990s but other labour market careers bore long-term scars [43,44].

4.2. The ‘Academic Route’

There was another trend during the 1980s which would have as much long-term significance for the viability of the existing transition regime as the ‘broken bridges’ awaiting young people without grammar school qualifications. There was a steady increase in the proportion of pupils who did achieve these qualifications, and they continued to find employment throughout the 1980s whether they entered the labour market at age 16, 18 or following higher education. ‘Academic’ qualifications seemed to guarantee employment [45]. This was just part of the context for an expansion of the academic route.

Another part of this context was the tendency for each cohort of parents to want their own children to do at least as well in education, and preferably better than they themselves. Additionally, parents became as ambitious for their daughters as for their sons. Women had won equal pay and opportunities. The contraceptive pill gave young and older women control over their own fertility. Young women were able to compete and establish themselves, prior to embarking on parenthood, in what had previously been mainly male occupations. The 1980s daughters were the first cohorts whose mothers had worked throughout the greater part of their children’s lives, usually in inferior jobs to those of their husbands. The daughters decided that their own futures would be different. By the mid-1980s they were equalling then exceeding boys’ performances in GCE O-level examinations, and went on to become the higher achievers in A-levels, then comprised the majority of undergraduate university entrants, then graduates [46]. Throughout the 1980s more young men, but even more young women were gaining academic qualifications. At the end of the 1970s, just 15 per cent of young people had entered higher education. By the early 1990s it was 30 per cent. The ‘alternative route’ was squeezed, but graduates themselves found that it was necessary to compete for ‘graduate jobs’.

At the beginning of the 20th century, middle-class parents who were willing to pay for secondary education thereby guaranteed their sons’ middle-class futures. After the 1944 Education Act, attendance at grammar school from age 11, which meant passing tests of ability and aptitude, was the guarantee. Then it became necessary to achieve the grades in grammar school exams that would open the gates to university, but by the end of the 1980s, even university graduates faced uncertain futures [47]. The old transition regime was failing to work as formerly no matter which route young people followed.

5. Regime Reconstruction

Reconstruction has not followed anyone’s masterplan. There has been no main driver of the changes. Government education, training, employment and welfare policies have set limits and created opportunities, sometimes with state financial support, for schools, colleges, universities, businesses and other training providers to pursue their own agendas, and in doing so offer different options to different groups of young people. Then, from among their options, young people have decided how to move their own lives forward. Interactively these initiatives by the various actors have reformed groupings of young people at the point of entry to the transition regime, created new employment class destinations, and routes linking the two.

5.1. Entry

We have seen that during ‘the breakdown’ the proportions of young people gaining grammar school qualifications at age 16, progressing to A-levels, then entering higher education, all rose steeply. The trend in school education was then turbo-charged by the 1988 Education Reform Act. Forecasts of a future knowledge economy were then at their height of fashion [48,49,50]. It was argued that the human capital of the country’s young people had to be enhanced so that they could keep abreast of new technologies and other advances in knowledge. There was faith that in the future there would be an abundance of knowledge jobs. Nearly all new job creation was to be at the top.

The Act’s method of raising attainments was competition between schools [51]. Local education authorities were stripped of their power to plan cooperation between schools in their areas. Each school was to be an independent unit for assessing its outputs. The Act introduced a national curriculum and a national programme of testing at ages 7, 11 and 14 (soon discarded), and at age 16 there was a new examination, the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), that would be taken by all 16-year-olds. The GCSE merged grammar school examinations (GCE O-levels) and a Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) which had been available since 1965 for pupils who were considered unsuited to the academically rigorous GCE O-levels. Schools’ national test and then GCSE results enabled national and local ‘league tables’ to be produced. These were intended to influence parents’ choices of schools for their children. This worked! Popular schools were able to expand their intakes which drove their budgets upwards. Other schools found themselves in a downward spiral. In order to achieve the best possible results schools were obliged to teach to tests and then GCSE subjects. In secondary schools, the most able pupils would be taught in sets and coached to achieve top grades. Other sets would be taught to achieve at least a ‘pass’ grade in all or most subjects [52]. Formally, all pupils were to pass the GCSE at one of seven grades, originally A–G but now 9–1. However, only grades A–C (now 9–4), the equivalents of passes in the old grammar school examination, were treated as true passes. The normal requirement for progression to A-levels was at least five GCSE A–Cs including maths and English. Schools and colleges were reluctant to lower their entry requirements for A-level courses lest this jeopardised their positions in another set of league tables. From age 12/13 the lower sets of secondary school pupils knew that the GCSE grades they were expected to gain would be regarded as failures, with predictable outcomes in levels of effort and motivation [53].

The outcome throughout the 1990s and 2000s was a steady rise in the proportions of 16-year-olds gaining at least 5 GCSEs, then A-levels at age 18. Staying in education beyond the statutory leaving age (still 16) became the norm, and the law was pulled along. The age of completing compulsory full-time ‘learning’ was raised to 17 in 2013 and 18 in 2015. By then two-thirds of 18/19-year-olds had qualifications that would admit them to universities [54,55,56].

Most of the one in three young people who fail to gain the GCSE grades necessary to continue along the academic route (as the grammar school route is now known) do not improve their qualifications despite, in law, being required to continue full-time learning until age 18. This legal requirement is not rigidly enforced. A fifth of England’s young people exit education with ‘nothing’, meaning no qualifications that have any value in the labour market [57,58]. In practice ‘full-time learning’ may mean no more than a job that includes at least 280 h per year of off-the-job training. The problem of the ‘bottom 20%’ has persisted throughout the 21st century. However, we know that among the 1958 birth cohort those with zero qualifications, even those lacking basic numeracy and literacy, found jobs without any difficulty. The zero-qualified were then over 50% of the age group. The difference in the 21st century is that they are now just 20%. The young people have not changed since the 1950s but their position in the changed transition regime is now chronically disadvantaged [59].

As under the pre-1980s transition regime, young people are still split into two groups at the point of entry, but there has been a major historical reversal. The achievers are now the majority and ‘the rest’ are a minority. In the mid-20th century, most young people left education with ‘nothing’. Leaving education with ‘nothing’ was simply normal at that time. By the early 21st century ‘the rest’ were a minority. Stigmatised [60] may be too strong a word, but (see below) they are likely to be avoided by employers with any scope for choice.

5.2. Destinations

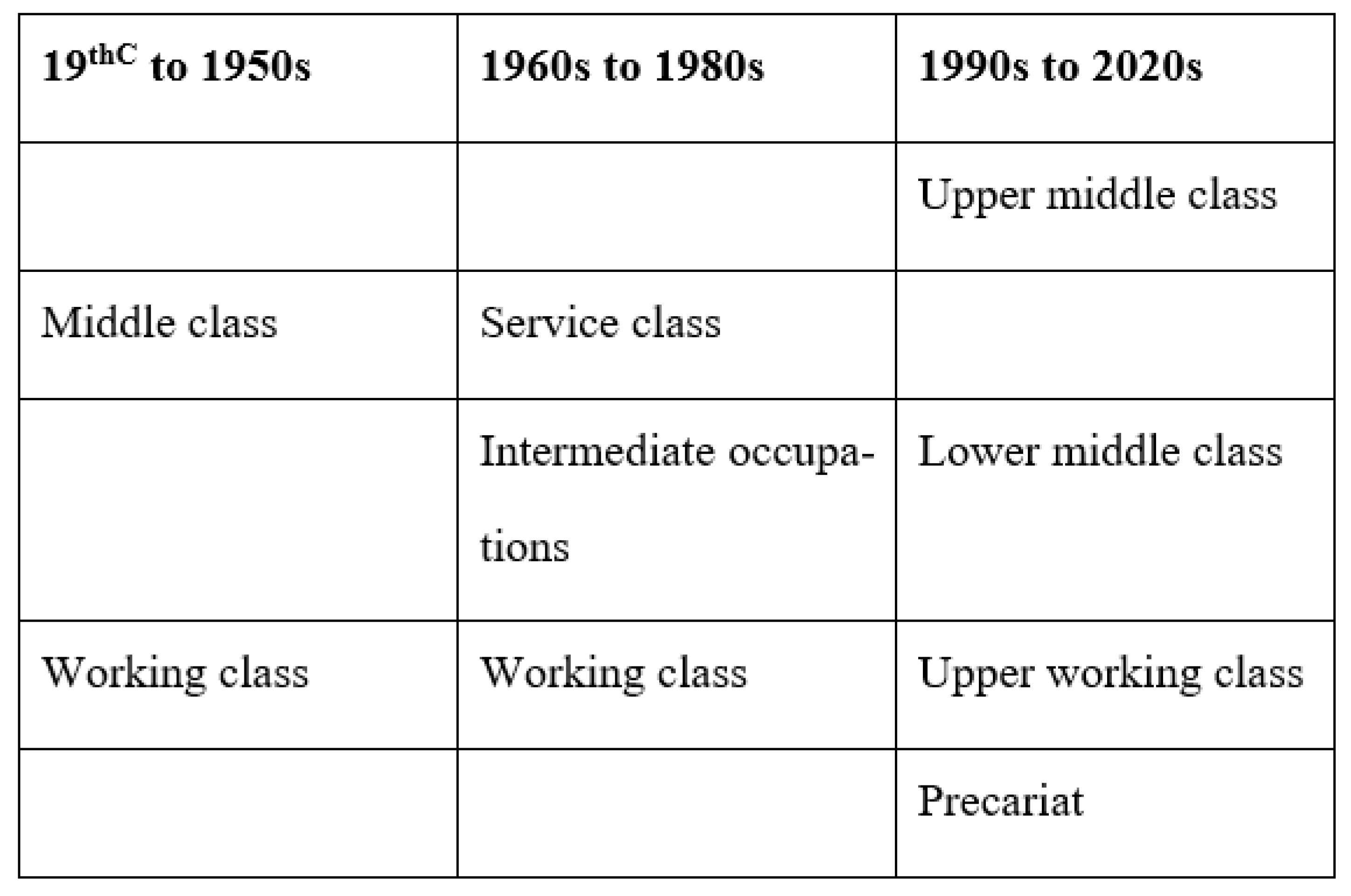

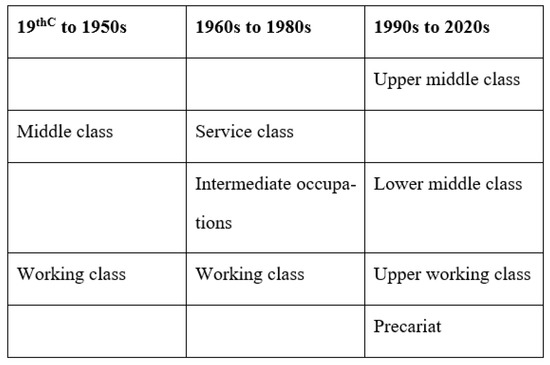

The two employment classes, a middle class and a working class, towards which young people could head earlier in the 20th century had become three before ‘the breakdown’. Intermediate lower-level non-manual jobs had been separated from a middle class of managers and professional occupations. During and since this breakdown the number has risen to four employment classes. As explained below, this has been due to the separation of a precariat [61] from an upper working class and a relocation of the main division among non-manuals.

The deregulation of the UK economy in the 1980s produced some spectacular rapid results. One was the sharp contraction of employment in manufacturing and extractive industries. Another was a surge in income inequality, driven by the spectacular earnings that became available in some finance businesses (but not high street banks). All controls on inward and outward flows of money were removed in 1979. Foreign banks were allowed to base and trade in London. Former demarcations such as between building societies and banks, retail and investment banking, stock jobbers and stockbrokers, were removed. Finance businesses developed new products, called derivatives, which they could sell to retail customers and trade among themselves. The total value of assets traded in financial markets, and the volume of trades, rose steeply. Shares in publicly listed companies became assets that were bought and sold in search of short- or medium-term capital gains [62]. Finance became an immensely profitable business. Before the end of the 1980s, new ‘masters of the universe’ were earning millions in salaries and bonuses. These rewards were shared with sections of professions that serviced finance, mainly law and accountancy, and with corporate executives who delivered returns on investments. An outcome has been new elite careers leading into high salary elite occupations [63,64]. Some other professions—doctors, dentists, vets and academics among them—have been able to persuade customers, usually the government, that their skills and contributions to society merit elite rewards. Most high street solicitors and accountants, estate agents, opticians, physiotherapists and other professions allied to medicine, school-teachers, librarians and social workers, have de facto been demoted into an upper tier of an expanded lower middle class.

The clear division within a formerly tiered but unitary working class has been due to the fastest growth during the last 30 years, contrary to forecasts of a knowledge economy, being in low paid jobs, also claimed to be low skilled [65]. Jobs can be precarious in a number of ways, usually in combination with being low paid, close to the age-related legal minimum rates that have applied since 1999. The jobs may also be for less than full-time hours, variable hours, and in 2019 the UK had almost a million workers on zero-hours contracts where employees are told from week-to-week, sometimes day-to-day, the hours when they are required to be at their places of work [66,67]. The jobs are in retail, distribution warehouses, bars, cafes, restaurants and delivering on foot, by cycle or motorised transport. Additionally, by 2019 Britain had over four million self-employed. They are not mostly high-tech start-ups but redundant or early retired professionals and managers who describe themselves as consultants, plus gardeners, cleaners and others who perform domestic services for households of elite earners. Precarious jobs have always existed but were usually secondary sources of household income whereas today around a quarter of working households rely on income supplements from means-tested welfare [68]. A harsh and punitive welfare regime will pressure the unemployed into any job, however few the hours at legally minimum pay [69]. The precariat has thereby been formed as a distinct employment class.

This precariat is now quite distinct from an upper working class that is employed in aerospace, pharmaceuticals, motor vehicle assembly and components manufacture, oil refineries, extractive industries, installing and maintaining water, energy and telecommunications infrastructure, construction, various types of repairs, and some public transport occupations such as train drivers. These jobs are as secure as any and the pay equals and sometimes exceeds that of lower professionals and managers.

Figure 1 depicts how destinations at points of exit from the prevailing transition regimes have changed since the early 20th century.

Figure 1.

Employment class destinations.

5.3. Career Routes and Groups

There have been two significant changes since ‘the breakdown’ in the routes available to young people at ages 16 and 18. The less significant of these changes has been the integration of vocational qualifications launched in the 1980s either into the academic route, alongside but usually taken in combination with A-levels or, in the case of lower-level vocational qualifications, made available to ‘the rest’ with enrolment acting as another signal that the young people lack the merit to tackle more demanding courses [70].

The more significant change has been the replacement of the training schemes of the 1980s with government-supported apprenticeships. The government began to support a limited number of ‘modern’ apprenticeships in 1994. These apprenticeships were at what would now be designated ‘advanced’ level. The apprentices were employees, and from 1999 they were paid at least the legal minimum rate for their ages. These apprenticeships proved popular with young people and recorded impressive outcomes in terms of progression in employment and earnings [71,72,73]. However, much has changed since 2015 when the age up to which young people were legally obliged to remain in full-time learning was raised to 18. The government then declared a target of training three million apprentices by 2020, and in the process, one might say that quality has been sacrificed for quantity. Since 2015 apprenticeships have been for all ages. Around half of government-supported apprentices are aged over 24. Additionally, apprenticeships are at different levels grouped into basic (officially called intermediate), advanced and higher. The latter include degree apprenticeships and the degrees may be post-graduate. By 2019 one in six young people were entering the workforce via a government-supported apprenticeship. Around half of the apprenticeships entered by under 24-year-olds are intermediate. Only a small proportion are degree apprenticeships, but their mere existence makes apprentices a status brand [74,75,76,77].

Just as under the pre-1980s transition regime when young people with grammar school qualifications had the widest choice of next steps, so under the reconstructed regime this applies to 18/19-year-olds who have qualified for university entry. Their alternatives are advanced and higher apprenticeships or equivalent jobs with training and prospects of career progression. An advanced apprenticeship will provide training to craft level in an upper working class occupation, or in general office or laboratory skills. A higher apprenticeship will train young people in an office speciality or to technician level, and a degree apprenticeship will take a young person to the base of a career in professions such as law, accountancy and engineering. Some employers offer equally attractive jobs outside the government-supported programme and thereby forego their opportunity to reclaim the training levy that has been imposed since 2017 at 0.5 per cent of all payrolls in excess of GBP 3 million. Firms stay outside the government-supported programme either to avoid bureaucratic hassle and treat the training levy as just another tax, or because they wish to customise training to their own requirements rather than a government template. For young people, the main problem with employer-based advanced and higher apprenticeships is that there are not enough.

Many 18-year-olds will have expected to progress to university for as long as they can remember. Their hopes are usually fulfilled. University is now the most common next step for Britain’s 18/19-year-olds. Two thirds are qualified to enter and by 2019 almost 40 per cent of the age group were taking this step forward. They are simply staying with ‘the crowd’. The numbers who can enrol in higher education are not fixed by the government but are an outcome of the interaction between the supply of and demand for places. Since 2015 university admissions have been uncapped, except for medicine where numbers trained are agreed with the British Medical Association which wants to avoid over-production. The result is persistent shortages, which has been addressed by recruiting from abroad. 2015 was not a major policy change because since 1963 governments have implicitly accepted a principle laid out in a 1963 official report that ‘places in higher education should be available for all who are qualified and wish to enter’ [78]. From the 1980s to the 2000s, governments worldwide (including the UK) became enthusiastic about human capital theory and assumed that a market economy would find ways of using the workforce’s capabilities in high value-added, well-paid jobs. However, the UK government is currently considering lowering the earnings floor at which repayments begin, extending the period before student debt is written off from 30 to 40 years, reducing the amount of fee loans that it will provide on low-value courses (graduates’ future earnings). In some cases, the reduction might be to zero. Ministers realise that they must be cautious because such actions could reduce enrolments at some universities and make them financially insolvent.

Under the pre-1980s transition regime, university graduates were an elite [79]. They had been among the minority who passed the test to gain admission to grammar schools or were in the sets in comprehensive schools that followed the grammar school curriculum and gained sufficiently good qualifications at 16 to be admitted to A-levels where their results were sufficiently good to gain entry to university. They had been successful at a series of hurdles at one of which most contemporaries had stumbled. Graduates were an elite and employers competed for their services. Nowadays most young people attend non-selective secondary schools where the majority gain the GCSE results that enable them to stay on the academic route and qualify for university entry. Most who are qualified take this step. Places are available for all who aspire to enter, and the university is also the default option for those who are unable to obtain suitable jobs or apprenticeships.

The big expansion in enrolments in higher education was in the 1980s during ‘the breakdown’: from 15 per cent of the age group at the end of the 1970s to 30 per cent by the early 1990s. Over the next 30 years, the enrolment rate crept up to just under 40 per cent. During this period state support for higher education students became less generous. Before the end of the 1980s, they lost welfare rights such as eligibility for housing benefits during term times and unemployment benefits during vacations. Means-tested maintenance grants began to be replaced by loans, and fees were introduced at GBP 1K per year in 1999, raised to GBP 3K in 2006, then to GBP 9K in 2012, funded by fee loans. By the beginning of the 2020s, the typical graduate had debts of around GBP 40–50K. Their reward has been eligibility to compete for an elite career, but there are far more competitors than opportunities. Chances depend on the subject studied at university. Economics and engineering give graduates an edge, but only degrees in medicine, dentistry and veterinary science guarantee an elite career. Chances also depend on the university at which a degree is awarded. Expansion has led to the creation of university league tables, sometimes based on tariffs (exam grades required for entry), sometimes on student or expert ratings, and sometimes on salaries five or more years after graduation. It helps immensely in pursuit of an elite career to gain experience in a temporary job, or in a paid or unpaid internship with a prospective employer, before or after graduation. It is also an advantage to be based in or to be able to move to London. Then, after surviving initial screens, it is necessary to be considered the type of recruit who will ‘fit in’, which tends to favour the seven per cent of the age group who have been educated in fee-paying schools [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Those who pass the entry hurdle then find that they have joined pools in which they must compete for career advancement. Most graduates do not survive initial screens and head for lower-middle-class jobs that they might have entered at age 18. This is the most common next step from university. Those making the step can feel that their career progress is simply normal [88,89]. At least graduates have hauled themselves clear of ‘the rest’, the third of 16-year-olds who do not move forward along the academic route. They are unlikely to be offered anything other than intermediate apprenticeships or minimum wage jobs. The truth is that ‘full-time learning’ is not strictly enforced. Sixteen and seventeen-year-olds can find jobs, especially in retail, distribution and hospitality. Their experience will assist in moving on to other such low paid jobs, but not ‘up’ the labour market.

Neither precariat jobs nor low achievers bring the other into existence. They are most likely to find one another because neither the employers nor the young people have alternatives. ‘The rest’ are a pool from which precarious jobs can be filled, and the jobs enable nearly all young people to escape prolonged unemployment.

6. Forthwith

In 2020 England’s reconstructed transition regime was tested by the spread of COVID-19, quickly followed by the first of what was to become successive national lockdowns. An immediate effect in 2020 was to rip 20 per cent from the country’s GDP. There were forecasts of a massive spike in unemployment, especially among young people given past experience, specifically in the 1970s and 1980s. There were immediate calls for a new generation of government special measures [90,91]. In the event, general unemployment was contained by the government’s furlough scheme which involved paying 80 per cent of the salaries of staff who were temporarily laid off. Among school and college leavers the reconstructed transition regime coped. During the pandemic youth (16–24-year-olds) unemployment rose in 2020 then fell to its earlier level in 2021. The rise and fall were entirely among students who lost then regained part-time jobs.

The proportion of 16–17-year-olds who remained in full-time education rose from 84 per cent to 88 per cent. The proportion of 18–19-year-olds entering higher education rose from just under 40 per cent to 44 per cent. Many full-time students lost former part-time jobs in 2020 but these were recovered during 2021. The number of 16–18-year-olds on government-supported apprenticeships declined from approximately 89,000 in 2018–19 to 65,000 in 2020–21. The decline among 19–24-year-olds was less steep; from 107,000 to 95,000. All of the declines were in intermediate (basic level) apprenticeships. Recruitment to advanced and higher apprenticeships remained stable. The decline in apprentice numbers was due to the training levy which was accompanied by more bureaucracy which firms wanted to avoid. Employers were not ceasing to employ and train young people. They were simply avoiding bureaucratic ‘hassle’ and, where relevant, were treating the training levy as just another tax. The outcome was that the employment rate among 18–24-year-olds who had completed full-time education fluctuated endlessly from 75 per cent to 78 per cent between 2019 and 2021 [92].

There could be trouble ahead, possibly among the 20 per cent who continue to leave education without any useful (in the labour market) qualifications, but possibly also among university graduates who feel burdened by student debt that they see no prospect of repaying [93]. It is estimated that around a third of graduates will make no repayments, which means that they will never earn as much as a median salary, the threshold for triggering repayments up to 2021 [94]. These are the main weaknesses in the new transition regime. The situations of these groups could be ‘normalised’, that is, accepted as just normal rather than problems that must be addressed, or they could be tackled by any combination of actors tweaking the transition regime with which England entered the 2020s still delivering Europe’s most rapid education-to-work transitions with youth unemployment and NEET rates below the European averages. These are the benefits of the transition regime. In 2022 the transition regime faced further challenges. The impact of Brexit on the economy and labour market had still to become visible and was being complicated by a cost-of-living crisis sparked by globally spiralling energy prices. While reluctant to predict, my hunch is that the reconstructed youth transition regime will cope.

Funding

This paper received no specific funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This paper did not involve any research on human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Armstrong, M. When the Milestones of Adulthood are Reached in the UK. Available online: www.statistica.com (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- Wallace, C.; Kovacheva, S. Youth in Society: The Construction and Deconstruction of Youth in East and West Europe; Macmillan: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. Regime change: Education to work transitions in England, 1980s-2020. J. Appl. Youth Stud. 2020, 3, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Group for Integrated Youth Research (EGRIS). Misleading trajectories: Transition dilemmas of young people in Eu-rope. J. Youth Stud. 2001, 4, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, A. Regimes of youth transitions: Choice, flexibility and security in young people’s experiences across different European contexts. Young 2006, 14, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A. Youth—Actor of social change? Differences and convergences across Europe. Studi Sociol. 2012, 1, 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, A. The struggle for ‘realistic’ career perspectives: Cooling-out versus recognition of aspirations in school-to-work-transitions. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 2015, 7, 18–42. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay, G. England and Wales Youth Cohort Study; Manpower Services Commission: Sheffield, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, A. Growing Up in a Classless Society? Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, A.; Raffe, S. Young People’s Routes into the Labour Market; Centre for Educational Sociology; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. Scotland’s Young People: 19 in ’95; The Scottish Office: Edinburgh, UK, 1996.

- Bratsberg, B.; Nyen, T.; Raaum, O. Economic returns to adult vocational qualifications. J. Educ. Work. 2020, 33, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjivassiliou Kari, P.; Tassinari, A.; Eichhorst, W.; Wozny, F. How does the performance of school-to-work transition regimes in the European Union vary? In Youth Labor in Transition; O’Reilly, J., Leschke, J., Ortlieb, R., Seeleib-Kaiser, M., Villa, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, I.; Noelke, C.; Gebel, M. (Eds.) Making the Transition: Education and Labor Market Entry in Central and Eastern Europe; Stanford University Press: Stanford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Lange, M.; Gesthuizen, M.; Wolbers, M.H.J. Youth labour market integration across Europe: The impact of cyclical, structural and institutional characteristics. Eur. Soc. 2014, 16, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelke, C.; Gebel, M.; Kogan, I. Uniform inequalities: Institutional differentiation and the transition from higher education to work in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 28, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, A.; Walter, A. Activating the disadvantaged: Variations in addressing youth transitions across Europe. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2007, 26, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffe, D. The concept of transition system. J. Educ. Work. 2008, 21, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raffe, D. Explaining national differences in education-work transitions: Twenty years of research on transition systems. Eur. Soc. 2014, 16, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, R.; Cefalo, R.; Kazepov, Y. School to work outcomes during the Great Recession, is the regional scale relevant for young people’s life chances? J. Youth Stud. 2020, 24, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranasinghe, R.; Chew, E.; Knight, G.; Siekmann, G. School-to-Work Pathways; National Center for Vocational Education Re-Search: Adelaide, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, E. Youth transitions to employment: Longitudinal evidence from marginalised young people in England. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 23, 1310–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Lyons-Amos, M. Diverse pathways in becoming an adult: The role of structure, agency and context. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 46, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rich, E.E. The Education Act 1870; Longman: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, D. The Rise of the Schooled Society; Routledge: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, O. Parity and Prestige in English Secondary Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J. Social Class and the Comprehensive School; Routledge: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, D.; Simon, B. The Evolution of the Comprehensive School; Routledge: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lethbridge, L. Servants: A Downstairs View of Twentieth Century Britain; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, S. The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class, 1910–2010; John Murray: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, D. The Blackcoated Worker; Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, R.; Jones, G. White-Collar Proletariat; Macmillan: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Goldthorpe, J.H.; Llewellyn, C.; Payne, C. Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, D.N.; Field, D. Young Workers; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, D.; Maguire, M. The Vanishing Youth Labour Market; Occasional Papers 3; Youthaid: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Coffield, F.; Borrill, C.; Marshall, S. Growing Up at the Margins; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bayly. The Work Experience Programme; Manpower Services Commission: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bedeman, T.; Harvey, J. Young People on YOP; Research and Development Series 3; Manpower Services Commission: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, D. Training Without Jobs; Macmillan: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.J.; Marsden, D.; Rickman, R.; Duncombe, J. Scheming for Youth: A Study of the YTS in the Enterprise Culture; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; Blundell, R.; Bozio, A.; Emmerson, C. Releasing Jobs for the Young? Early Retirement and Youth Unemployment in the United Kingdom; Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, I.; Clarke, J.; Cohen, P.; Finn, D.; Moore, R.; Willis, P. Schooling for the Dole; Macmillan: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Droy, L.; Goodwin, J.; O’Connor, H. Liminality, Marginalisation and Low-Skilled Work: Mapping Long-term Labour Market Difficulty Following Participation in the 1980s Government-Sponsored Youth Training Schemes, Occasional Paper 7; School of Media, Com-Munication and Sociology; University of Leicester: Leicester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, H. The Milltown Boys Revisited; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. Generation equity and inequity: Gilded and jilted generations in Britain since 1945. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnot, M.; David, M.; Weiner, G. Educational Reforms and Gender Equality in Schools; Equal Opportunities Commission: Man-chester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, G. The New Graduate Supply Shock; National Institute of Economic and Social Research: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Employment Department. Labour Market and Skill Trends 1994/95; Employment Department: London, UK, 1993.

- Employment Department. Labour Market and Skill Trends, 1995/96; Skills and Enterprise Network: Nottingham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, R.R. The Work of Nations: A Blueprint for the Future; Simon and Schuster: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chitty, C. Towards a New Education System: The Victory of the New Right? Falmer: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Playford, C.J.; Gayle, V. The concealed middle? An exploration of ordinary young people and school GCSE subject area at-tainment. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, S. Education in a Post-Welfare Society; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bursnall, M.; Naddeo, A.; Speckesser, S. Young People’s Education Choices and Progression to Higher Education; National Institute of Economic and Social Research: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. Key Stage 4 Including Multi-Academy Trust Performance 2018 (Revised); Department for Education: London, UK, 2019.

- OFQUAL. GCSEs in 2019, All Entries in All Subjects, England Only; Ofqual: London, UK, 2019.

- Brooks, G.; Giles, K.; Harman, J.; Kendall, S.; Rees, F.; Whittaker, S. Assembling the Fragments: A Review of Research on Basic Adult Skills; Department for Education and Employment: Sheffield, UK, 2001.

- Children’s Commissioner. The Children Leaving School with Nothing; Children’s Commissioner: London, UK, 2019.

- Bynner, J.; Parsons, S. Qualifications, basic skills and accelerating social exclusion. J. Educ. Work. 2001, 14, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solga, H. Stigmatization by negative selection: Explaining less-educated people’s decreasing employment opportunities. Eur. Soc. 2002, 18, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, G. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lapavitsas, C. Theorizing financialization. Work. Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, T. The Myths of Both Left and Right Stop Us Seeing the True Story of Inequality; The Observer: London, UK, 2020; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M. Inequality; Sage: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goos, M.; Manning, A. Lousy and Lovely Jobs: The Rising Polarisation of Work in Britain; Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. People in Employment on a Zero-Hours Contract; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2017.

- Trade Union Congress. Four in Five Jobs Created Since 2010 Have Been in Low Paid Industries; Trade Union Congress: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hick, R.; Lanau, A. In-Work Poverty in the UK; Cardiff University: Cardiff, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. A job, any job: The UK benefits system and employment services in a age of austerity. Obs. Soc. Br. 2017, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A. Review of Vocational Education: The Wolf Report; Department for Education: London, UK, 2011.

- McIntosh, S. A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Apprenticeships and Other Vocational Qualifications; Department for Education and Skills: Nottingham, UK, 2007.

- Paton, G. Graduates Earning Less than Those on Apprenticeships; Telegraph: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton Trust. Higher Apprenticeships Better for Jobs than University Degree Say Public—New Polling for Sutton Trust/Pearson Summit. Available online: www.suttontrust.com (accessed on 11 August 2014).

- Engeli, A.; Turner, D. Degree Apprenticeships Motivations Research; Wavehill Social and Economic Research: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, T. Higher Apprenticeships: Up to Standard? Policy Connect: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Office for Students. Degree Apprenticeships: A Viable Alternative? Insight; Office for Students: London, UK, 2019.

- Powell, A. Apprenticeships and Skills Policy in England; House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins Report. Higher Education; Committee on Higher Education; HMSO: London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsall, R.K.; Poole, A.; Kuhn, A. Graduates: The Sociology of an Elite; Methuen: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Boliver, V. Are there distinctive clusters of higher and lower status universities in the UK? Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2015, 41, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, S.; Laurison, D. The Class Ceiling: Why it Pays to Be Privileged; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.; Laurison, D. Miles, A. Breaking the “class” ceiling? Social mobility into Britain’s elite occupations. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 63, 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Fliers Research. The Graduate Market in 2019; High Fliers Research: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holford, A. Access to and Returns from Unpaid Graduate Internships, Discussion Paper 1ZA; Institute for Labour Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, N.; Allen, K. “Talent spotting” or “social magic”? Inequality, cultural sorting and constructions of the ideal graduate in elite professions. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 67, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasagar, J. Interns Will Secure a Third of Graduate Jobs; The Guardian: London, UK, 2011; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling, P.; Savage, M. Entry into elite positions and the stratification of higher education in Britain. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 63, 290–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. Employment and Earnings Outcomes of Higher Education; Department for Education: London, UK, 2017.

- Office for National Statistics. Graduates in the UK Labour Market: 2017; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2019.

- Henehan, K. Class of 2020: Education Leavers in the Current Crisis; Resolution Foundation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trade Union Congress. Young Workers are Most at Risk from Job Losses due to the Coronavirus Crisis; Trade Union Congress: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. Education-to-work transitions during the Covid-19 lockdowns in Britain, 2020–2021. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2021, 11, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, C.; de Gayardon, A. Hidden Voices: Graduates’ Perspectives on the Student Loan System in England; Higher Education Policy Institute: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, N. No Easy Answers: English Student Finance in the Spending Review, HEPI Policy Note 31; Higher Education Policy Institute: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).