Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Longing for “Greater” Days

3. What Threatens White America?

4. Conservative Media’s Grasp

5. The Current Study

- (1)

- Are perceptions of social issues associated with status threat for White Americans?

- (2)

- Are perceptions of social issues associated with affiliation with the Alt-Right for White Americans controlling for status threat?

- (3)

- Does trust in conservative media influence these associations?

6. Method

6.1. Data

6.2. Measures

6.2.1. Dependent Variable

6.2.2. Independent Variables

6.2.3. Conditioning Variable

6.2.4. Control Variables

6.3. Analytical Strategy

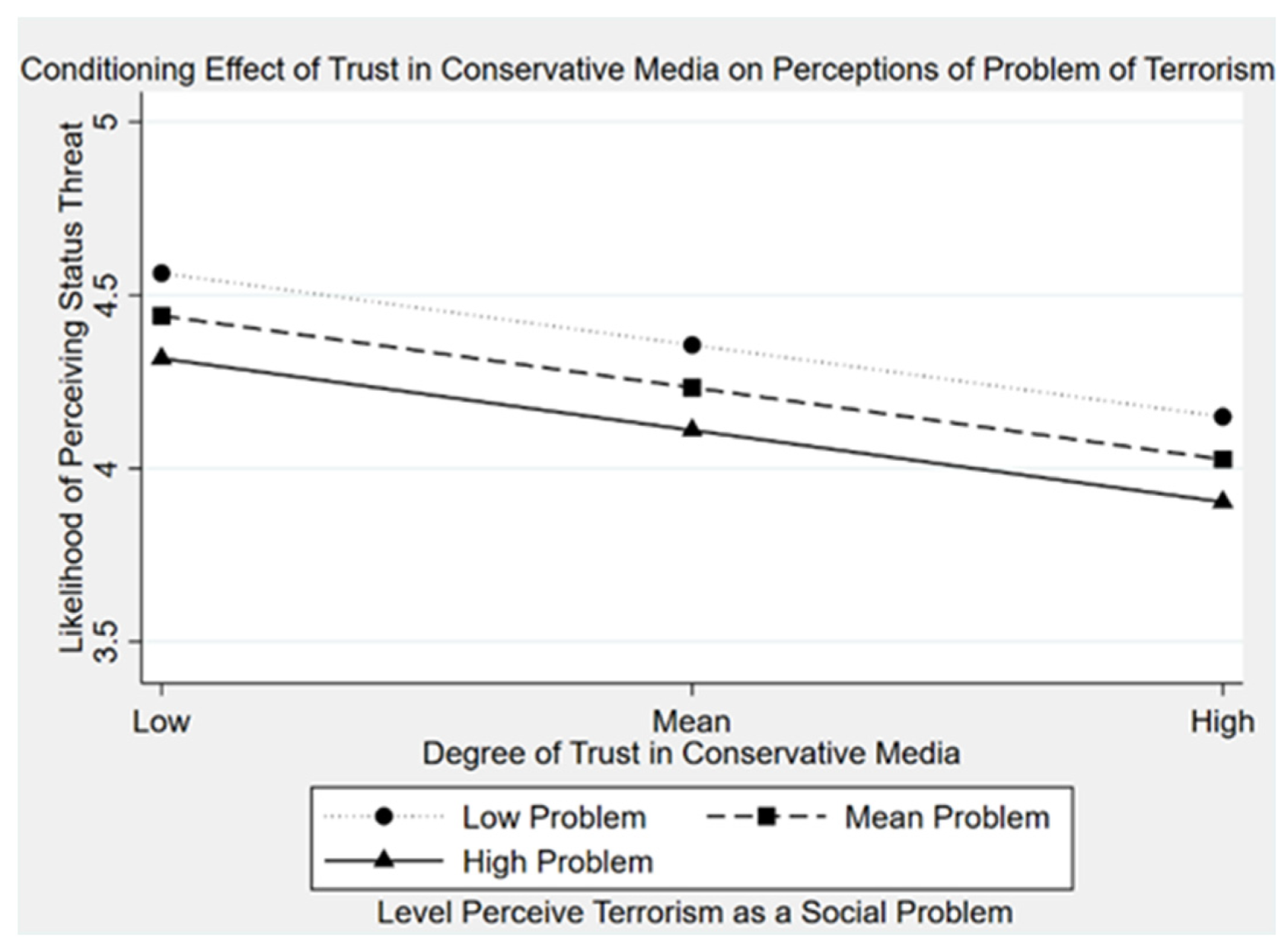

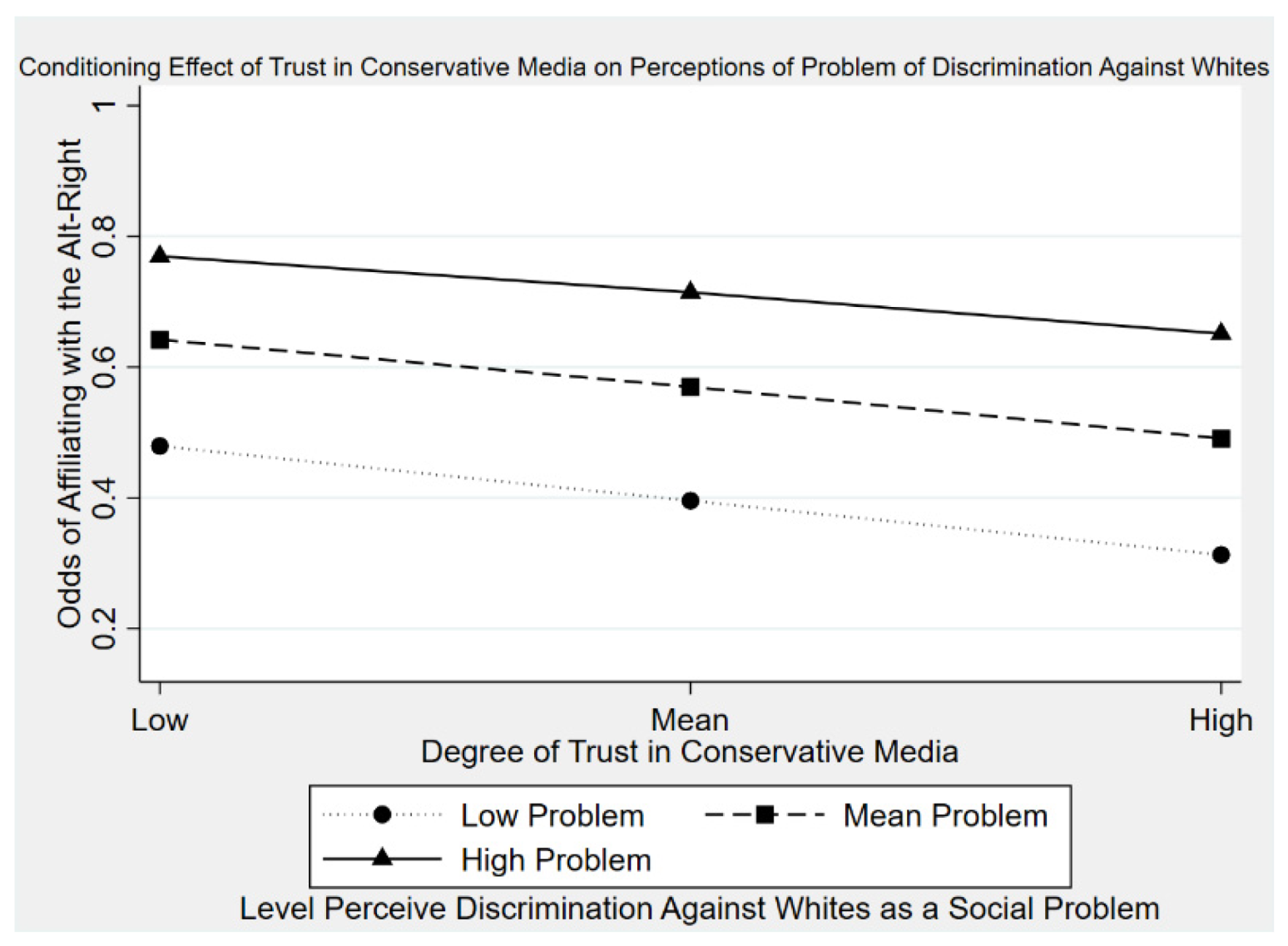

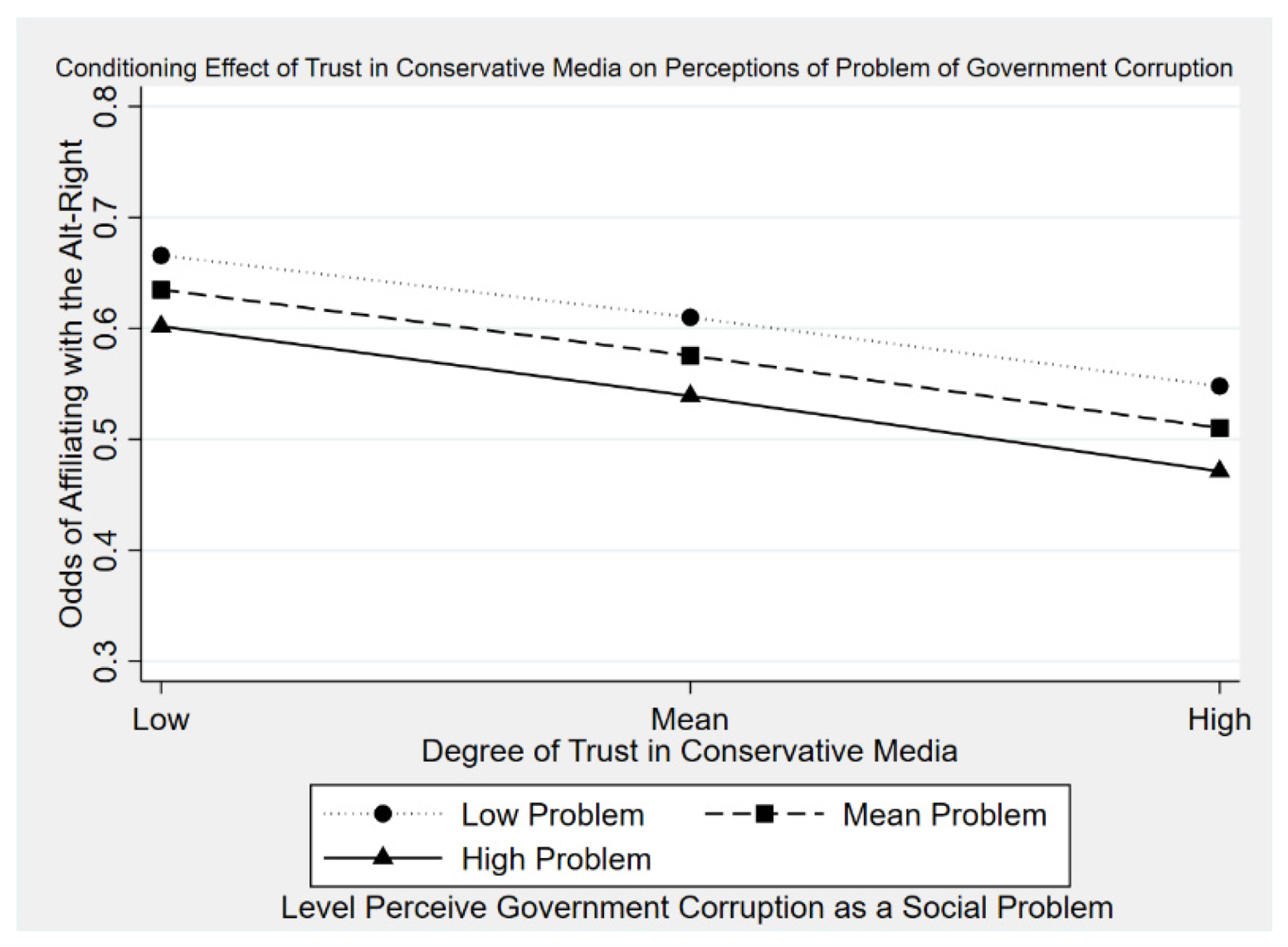

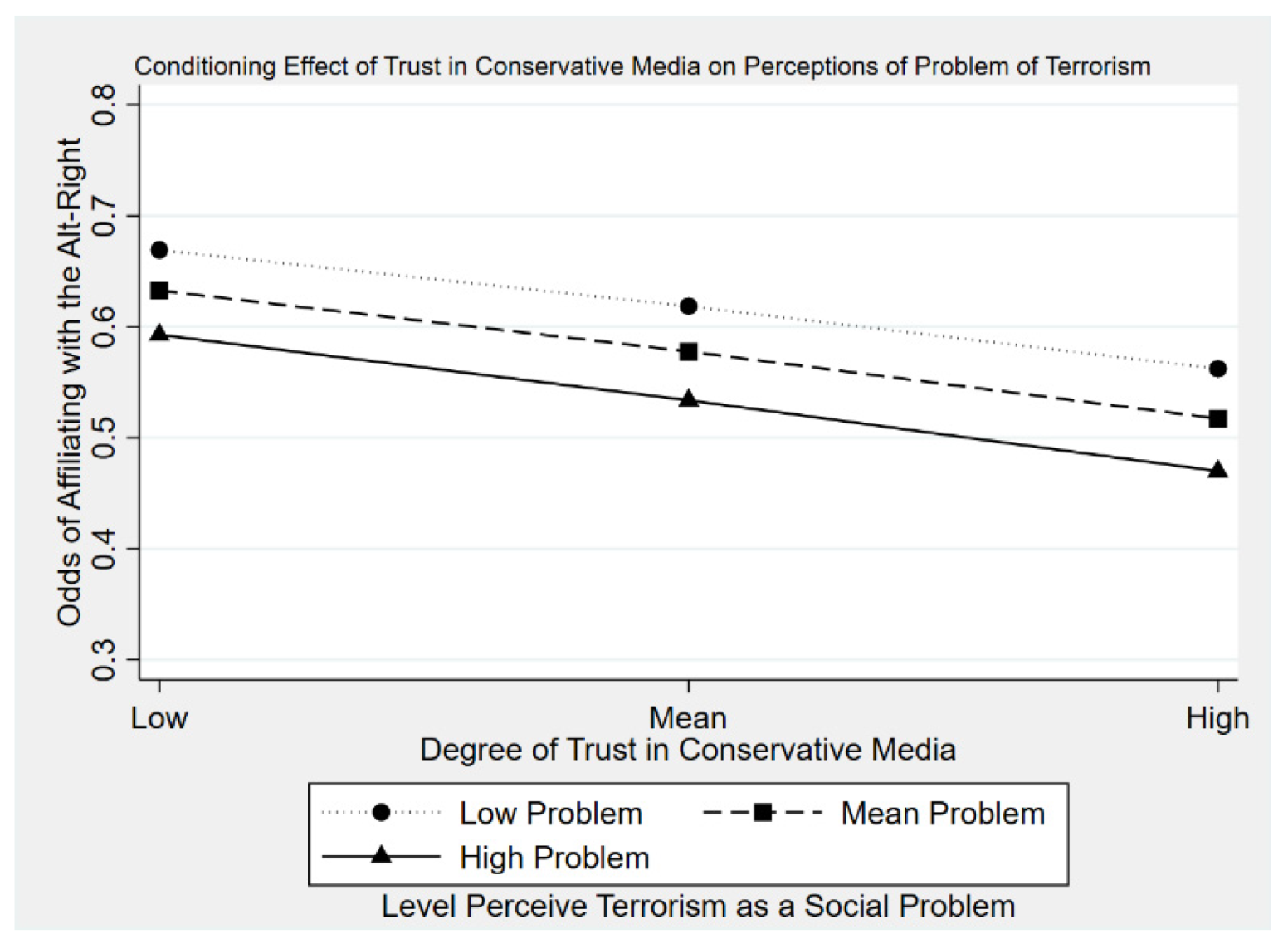

7. Results

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crandall, C.S.; Miller, J.M.; White, M.H. Changing Norms Following the 2016 US Presidential Election: The Trump Effect on Prejudice. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2018, 9, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States. Department of Justice. 2017 Hate Crime Statistics; Federal Bureau of Investigation: Washington DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2017 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Rosa, J.; Bonilla, Y. Deprovincializing Trump, Decolonizing Diversity, and Unsettling Anthropology. Am. Ethnol. 2017, 44, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Schwarz, C. From Hashtag to Hate Crime: Twitter and Anti-Minority Sentiment. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barkun, M. President Trump and the “Fringe”. Terror. Political Violence 2017, 29, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, D.; Krasa, S.; Polborn, M. Political Polarization and the Electoral Effects of Media Bias. J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 1092–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mutz, D.C. How the Mass Media Divide Us. Red Blue Nation 2007, 1, 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Forscher, P.S.; Kteily, N.S. A Psychological Profile of the Alt-Right. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 90–116. Available online: https://osf.io/xge8q/ (accessed on 1 May 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirby, J. “Black Lives Matter” Has Become a Global Rallying Cry against Racism and Police Brutality. Vox. 7 June 2020. Available online: https://www.vox.com/2020/6/12/21285244/black-lives-matter-global-protests-george-floyd-uk-belgium (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Somvichian-Clausen, A. What the 2020 Black Lives Matter Protests Have Achieved So Far. Hill Chang. Am. 2020. Available online: https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/equality/502121-what-the-2020-black-lives-matter-protests-have-achieved-so (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Mezzofiore, G.; Polglase, K. White Supremacists Openly Organize Racial Violence on Telegram, Report Finds. Cable News Netw. 2020. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/26/tech/white-supremacists-telegram-racism-intl/index.html (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Hochschild, A.R. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, R. The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Small-Town America; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, S.J.; Partridge, M.D.; Stephens, H.M. The Economic Status of Rural America in the President Trump Era and Beyond. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, H.M.; Isom Scott, D.A. Alt-White? A Gendered Look at “Victim” Ideology and the Alt-Right. Vict. Offenders 2020, 15, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, A.L. White Man Falling: Race, Gender, and White Supremacy; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Isom, D.A.; Mikell, T.C.; Boehme, H.M. White America, Threat to the Status Quo, and Affiliation with the Alt-Right: A Qualitative Approach. Sociol. Spectr. 2021, 41, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isom Scott, D.A. Understanding White Americans’ perceptions of “reverse” discrimination: An application of a new theory of status dissonance. In Advances in Group Processes; Thye, S.R., Lawler, E.J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; Volume 35, pp. 129–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M. Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era; Bold Type Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Outten, H.R.; Schmitt, M.T.; Miller, D.A.; Garcia, A.L. Feeling Threatened about the Future: Whites’ Emotional Reactions to Anticipated Ethnic Demographic Changes. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, R.; Feinberg, M.; Wetts, R. Threats to Racial Status Promote Tea Party Support among White Americans. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorski, P. Why evangelicals voted for trump: A critical cultural sociology. In Politics of Meaning/Meaning of Politics; Mast, J.L., Alexander, J.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz, D.C. Status Threat, Not Economic Hardship, Explains the 2016 Presidential Vote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E4330–E4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andaya, E. “I’m Building a Wall around My Uterus”: Abortion Politics and the Politics of Othering in Trump’s America. Cult. Anthropol. 2019, 34, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Trump, Trans Students and Transnational Progress. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, M.; Dassonneville, R. Explaining the Trump Vote: The Effect of Racist Resentment and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments. PS Political Sci. Politics 2018, 51, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sides, J.; Tesler, M.; Vavreck, L. Hunting Where the Ducks Are: Activating Support for Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican Primary. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 2018, 28, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, P. Chokehold: Policing Black Men; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, T. Dear White America: Letter to a New Minority; City Lights Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo, L.D. Whites’ Opposition to Busing: Symbolic Racism or Realistic Group Conflict? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In The Social Psychology of Inter-Group Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, G.H. Mind, Self, and Society from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Hewston, M.; Rubin, M.; Willis, H. Intergroup Bias. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 575–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blalock, H.M. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1958, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, L.; Hutchings, V.L. Perceptions of Racial Group Competition: Extending Blumer’s Theory of Group Position to a Multiracial Social Context. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, L.D. Prejudice as Group Position: Microfoundations of a Sociological Approach to Racism and Race Relations. J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.A.; Richeson, J.A. On the Precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America: Perceived Status Threat from the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans’ Political Ideology. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, A.E. (Ed.) Social Threat and Social Control; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stults, B.J.; Baumer, E.P. Racial Context and Police Force Size: Evaluating the Empirical Validity of the Minority Threat Perspective. Am. J. Sociol. 2007, 113, 507–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitle, D.; D’Alessio, S.J.; Stolzenberg, L. Racial Threat and Social Control: A Test of the Political, Economic, and Threat of Black Crime Hypotheses. Soc. Forces 2002, 81, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.F.; Stults, B.J.; Rice, S.K. Racial Threat, Concentrated Disadvantage and Social Control: Considering the Macro-Level Sources of Variation in Arrests. Criminology 2005, 43, 1111–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, B.; Jacobs, D. Racial Threat, Partisan Politics, and Racial Disparities in Prison Admissions: A Panel Analysis. Criminology 2009, 47, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.A. Black Threat and Incarceration in Postbellum Georgia. Soc. Forces 1990, 69, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Chiricos, T.; Kleck, G. Race, Racial Threat, and Sentencing of Habitual Offenders. Criminology 1998, 36, 481–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, M.S.; Johnson, K.A. Race, Ethnicity, and Habitual-Offender Sentencing: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual and Contextual Threat. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2008, 19, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricos, T.; Welch, K.; Gertz, M. Racial Typification of Crime and Support for Punitive Measures. Criminology 2004, 42, 358–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, K.; Payne, A.A.; Chiricos, T.; Gertz, M. The Typification of Hispanics as Criminals and Support for Punitive Crime Control Policies. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 40, 822–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmeyer, B.; Warren, P.Y.; Siennick, S.E.; Neptune, M. Racial, Ethnic, and Immigrant Threat: Is There a New Criminal Threat on State Sentencing? J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2015, 52, 62–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mears, D.P. A Multilevel Test of Minority Threat Effects on Sentencing. J. Quant. Criminol. 2010, 26, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.R.; Fast, N.J.; Ybarra, O. Group Status, Perceptions of Threat, and Support for Social Inequality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Smith-Crowe, K.; Brief, A.P.; Dietz, J.; Watkins, M.B. When Birds of a Feather Flock Together and When They Do Not: Status Composition, Social Dominance Orientation, and Organizational Attractiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garimella, K.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Gionis, A.; Mathioudakis, M. Political Discourse on Social Media: Echo Chambers, Gatekeepers, and the Price of Bipartisanship. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 913–922. [Google Scholar]

- Phua, J.J. Sports Fans and Media Use: Influence on Sports Fan Identification and Collective Self-Esteem. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2010, 3, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.J. The Interplay between Media Use and Interpersonal Communication in the Context of Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors: Reinforcing or Substituting? Mass Commun. Soc. 2009, 13, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.D.; MacGillivray, M.S. Self-Perceived Influences of Family, Friends, and Media on Adolescent Clothing Choice. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 1998, 26, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K. May the Weak Force Be with You: The Power of the Mass Media in Modern Politics. Eur. J. Political Res. 2006, 45, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, S.; Westwood, S.J. Selective Exposure in the Age of Social Media: Endorsements Trump Partisan Source Affiliation When Selecting News Online. Commun. Res. 2014, 41, 1042–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.J.; Yurukoglu, A. Bias in Cable News: Persuasion and Polarization. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 2565–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bode, L. Political News in the News Feed: Learning Politics from Social Media. Mass Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boxell, L.; Gentzkow, M.; Shapiro, J.M. Is the Internet Causing Political Polarization? Evidence from Demographics (No. w23258); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23258/w23258.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- DellaVigna, S.; Kaplan, E. The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 1187–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auletta, K. Vox Fox: How Roger Ailes and Fox News are changing cable news. New Yorker 2003, 26, 1187–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, S. Crazy Like a FOX: The Inside Story of How Fox News Beat CNN; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.S. The Fox News Factor. Harv. Int. J. Press/Politics 2005, 10, 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T. The Outsider on the Inside: Donald Trump’s Twitter Activity and the Rhetoric of Separation from Washington Culture. Atl. J. Commun. 2019, 27, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T. Trump TV: The Trump Campaign’s Real News Update as Competitor to Cable News. Vis. Commun. Q. 2019, 26, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yglesias, M. The Case for Fox News Studies. Political Commun. 2018, 35, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, V. Media Failures in the Age of Trump. Political Econ. Commun. 2017, 4, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, J.M. History of Fake News. Libr. Technol. Rep. 2017, 53, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Polletta, F.; Callahan, J. Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the trump era. In Politics of Meaning/Meaning of Politics; Mast, J.L., Alexander, J.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Persily, N. The 2016 US Election: Can Democracy Survive the Internet? J. Democr. 2017, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern Poverty Law Center. Alt-Right. Available online: https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/alt-right (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Daniels, J. The Algorithmic Rise of the “Alt-Right”. Contexts 2018, 17, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, J. The Self-Radicalization of White Men: “Fake News” and the Affective Networking of Paranoia. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2018, 11, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A. The Alt-Right: Reactionary Rehabilitation for White Masculinity. Soundings 2017, 66, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right; John Hunt Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S.; Hahn, K.S. Red Media, Blue Media: Evidence of Ideological Selectivity in Media Use. J. Commun. 2009, 59, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, H.; Feldman, C.S. No Time to Think: The Menace of Media Speed and the 24-Hour News Cycle; A&C Black: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, E.; Morelli, M.; Van Weelden, R. Elections and Divisiveness: Theory and Evidence. J. Politics 2017, 79, 1268–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olzak, S. The Dynamics of Ethnic Competition and Conflict; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Isom Scott, D.A.; Andersen, T.S. ‘Whitelash?’ Status Threat, Anger, and White America: A General Strain Theory Approach. J. Crime Justice 2020, 43, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardina, A. White Identity Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, E. Why We’re Polarized; Profile Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, R.N.; Behrend, T.S. An Inconvenient Truth: Arbitrary Distinctions between Organizational, Mechanical Turk, and Other Convenience Samples. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hauser, D.J.; Schwarz, N. Attentive Turkers: MTurk Participants Perform Better on Online Attention Checks than Do Subject Pool Participants. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.A.; Sabat, I.E.; Martinez, L.R.; Weaver, K.; Xu, S. A Convenient Solution: Using MTurk to Sample from Hard-To-Reach Populations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.J.; Paolacci, G. Lie for a Dime: When Most Prescreening Responses are Honest but Most Study Participants are Impostors. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levay, K.E.; Freese, J.; Druckman, J.N. The Demographic and Political Composition of Mechanical Turk Samples. Sage Open 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faris, R.; Roberts, H.; Etling, B.; Bourassa, N.; Zuckerman, E.; Benkler, Y. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Cent. Res. Publ. 2017, 6. Available online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Marwick, A.; Lewis, R. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online; Data & Society Research Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://datasociety.net/library/media-manipulation-and-disinfo-online/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Jost, J.T.; Federico, C.M.; Napier, J.L. Political Ideology: Its Structure, Functions, and Elective Affinities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dey, E.L. Undergraduate Political Attitudes: Peer Influence in Changing Social Contexts. J. High. Educ. 1997, 68, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiel, A.V.; Mervielde, I. Explaining Conservative Beliefs and Political Preferences: A Comparison of Social Dominance Orientation and Authoritarianism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccato, M.; Ricolfi, L. On the Correlation between Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 27, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.K.; Sidanius, J.; Kteily, N.; Sheehy-Skeffington, J.; Pratto, F.; Henkel, K.E.; Foels, R.; Stewart, A.L. The Nature of Social Dominance Orientation: Theorizing and Measuring Preferences for Intergroup Inequality Using the New SDO7 Scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCandless, D.; Posavec, S. Left vs. Right (US). December 2010. Available online: https://informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/left-vs-right-us/ (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Crawford, J.T.; Brandt, M.J.; Inbar, Y.; Chambers, J.R.; Motyl, M. Social and Economic Ideologies Differentially Predict Prejudice across the Political Spectrum, but Social Issues are Most Divisive. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 112, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vaidhyanathan, S. Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, J. Trump is a Dangerous Media Mastermind. CNN. 21 July 2019. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/21/opinions/trump-racist-tweet-mastery-media-coverage-zelizer/index.html (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Peters, J.W. Michael Savage Has Doubts About Trump. His Conservative Radio Audience Does Not. The New York Times. 18 June 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/18/us/politics/michael-savage-trump.html (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Darcy, O. Trump Invites Right-Wing Extremists to White House ‘Social Media Summit’. CNN. 11 July 2019. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/10/tech/white-house-social-media-summit/index.html (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Rosenwald, B. Trump Just Launched the Newest Phase of the GOP’s Romance with Right-Wing Media. The Washington Post. 13 July 2019. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/13/trump-just-launched-newest-phase-gops-romance-with-right-wing-media/?utm_term=.92ec6eea1f48 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Rummler, O. Trump Supporters Echo His Racist Tweets, Chanting ‘Send Her Back’. Axios. 17 July 2019. Available online: https://www.axios.com/trump-supporters-chant-send-her-back-rally-echoing-racist-tweets-274f0261-f69b-4755-906d-3da7f06582fb.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Holt, J. #StopTheSteal: Timeline of Social Media and Extremist Activities Leading to 1/6 Insurrection. Just Security. 10 February 2021. Available online: https://www.justsecurity.org/74622/stopthesteal-timeline-of-social-media-and-extremist-activities-leading-to-1-6-insurrection/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Hauck, G.; Barfield Barry, D. ‘Double Standard’: Biden, Black Lawmakers and Activists Decry Police Response to Attack on US Capitol. USA Today. 13 January 2021. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/01/06/us-capitol-attack-compared-response-black-lives-matter-protests/6570528002/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Hymes, C.; McDonald, C.; Watson, E. What We Know About the “Unprecedented” U.S. Capitol Riot Arrests. CBS News. 16 April 2021. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/capitol-riot-arrests-2021-04-16/ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Stein, R.; Willis, H.; Miller, D.; Schmidt, M.S.U.S. Capitol Riot. The New York Times. 22 March 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/spotlight/us-capitol-riots-investigations (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Heft, A.; Mayerhöffer, E.; Reinhardt, S.; Knüpfer, C. Beyond Breitbart: Right-Wing Digital News Infrastructures in Six Western Democracies. Policy Internet 2019, 12, 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, T.J. The Rise of the Alt-Right; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boatman, E. The Kids are Alt-Right: How Media and the Law Enable White Supremacist Groups to Recruit and Radicalize Emotionally Vulnerable Individuals. Law J. Soc. Justice 2019, 12, 2–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaher, C. Mainstreaming White Supremacy: A Twitter Analysis of the American ‘Alt-Right’. J. Fem. Geogr. 2021, 28, 224–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Dus, N.; Nouri, L. The Discourse of the US Alt-Right Online—A Case Study of the Traditionalist Worker Party Blog. Crit. Discourse Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizo-Lledot, A.; Torregrosa, J.; Bello-Orgaz, G.; Thorburn, J.; Camacho, D. Describing Alt-Right Communities and Their Discourse on Twitter during the 2018 US Mid-term Elections. In Complex Networks 2019: Complex Networks and Their Applications VIII; Cherifi, H., Gaito, S., Mendes, J., Moro, E., Rocha, L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 882, pp. 427–439. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, L. Alt-Right Pipeline: Individual Journeys to Extremism Online. First Monday 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa, J.; Panizo-Lledot, Á.; Bello-Orgaz, G.; Camacho, D. Analyzing the Relationship between Relevance and Extremist Discourse in an Alt-Right Network on Twitter. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.H.; Ottoni, R.; West, R.; Almeida, V.A.F.; Meira, W. Auditing radicalization pathways on YouTube. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; ACM Digital Library, 2020; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3351095.3372879 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Schulze, H. Who Uses Right-Wing Alternative Online Media? An Exploration of Audience Characteristics. Politics Gov. 2020, 8, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zeeuw, D.; Hagen, S.; Peeters, S.; Jokubauskaitė, E. Tracing Normiefication: A Cross-Platform Analysis of the QAnon Conspiracy Theory. First Monday 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blee, K.M. Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rogers, S.E. They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South; Yale University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, A.L. Constructing Whiteness: The Intersections of Race and Gender in US White Supremacist Discourse. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1998, 21, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isom, D.A.; Boehme, H.M.; Cann, D.; Wilson, A. The White Right: A Gendered Look at the Links between ‘Victim’ Ideology and Anti-Black Lives Matter Sentiments in the Era of Trump. Crit. Sociol. in press.

- Riggle, E.D.; Rostosky, S.S.; Reedy, C.S. Online Surveys for BGLT Research: Issues and Techniques. J. Homosex. 2005, 49, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessl, K.S.; Huber, J.; Netzer, O. Mturk Character Misrepresentation: Assessment and Solutions. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman, J.; Tavernise, S.; Baker, M. Why These Protesters Aren’t Staying Home for Coronavirus Orders. The New York Times. 23 April 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/us/coronavirus-protesters.html (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Riess, R. Protesters in Michigan Demonstrate Against Stay-At-Home Order. CNN. 20 April 2020. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/us/live-news/us-coronavirus-update-04-30-20/h_e90047bd263620ce7d71d643aba02ed0 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Warren, M.; Marquez, M.; Scannell, K.; Perez, E. Conservative groups boost anti-stay-at-home protests. CNN. 20 April 2020. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/20/politics/stay-at-home-protests-conservative-groups-support/index.html (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Russonello, G. Why Most Americans Support the Protests. The New York Times. 5 June 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/05/us/politics/polling-george-floyd-protests-racism.html (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Anti-Defamation League. Small but Vocal Array of Right Wing Extremists Appearing at Protests. June 2020. Available online: https://www.adl.org/blog/small-but-vocal-array-of-right-wing-extremists-appearing-at-protests (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Kilgo, D. Riot or Resistance? The Way the Media Frames the Unrest in Minneapolis Will Shape the Public’s View of Protest. Nieman Foundation: Harvard University, May 2020. Available online: https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/05/riot-or-resistance-the-way-the-media-frames-the-unrest-in-minneapolis-will-shape-the-publics-view-of-protest/?relatedstory (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Papenfuss, M. FBI Chief Christopher Wray Warns of ‘Persistent, Pervasive’ White Supremacy Threat. Huffpost. 4 April 2019. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/fbi-christopher-wray-white-supremacy-pervasive-threat_n_5ca68631e4b0dca032fed83f (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Estes, A.C.; How Neo-Nazis Used the Internet to Instigate a Right-Wing Extremist Crisis. Vox. 2 February 2021. Available online: https://www.vox.com/recode/22256387/facebook-telegram-qanon-proud-boys-alt-right-hate-groups (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Romano, A. Baked Alaska’s Clout-Chasing Spiral into White Supremacy is an Internet Morality Tale. Vox. 17 January 2021. Available online: https://www.vox.com/22235691/baked-alaska-tim-gionet-arrest-capitol-riot-alt-right-buzzfeed (accessed on 1 April 2021).

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Alt-Right Affiliation | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| B | Government Corruption | −0.113 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| C | Washington Elites | −0.093 * | 0.559 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| D | Wealth Gap | −0.340 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.436 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| E | Discrimination Against Whites | 0.519 ** | 0.019 | 0.020 | −0.268 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| F | Discrimination Against Blacks | −0.433 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.168 ** | 0.525 ** | −0.394 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| G | Political Correctness | 0.375 ** | 0.147 ** | 0.197 ** | −0.181 ** | 0.517 ** | −0.295 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| H | Discrimination Against Men | 0.383 ** | 0.032 | 0.074 * | −0.176 ** | 0.666 ** | −0.219 ** | 0.402 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| I | Discrimination Against Women | −0.270 ** | 0.112 ** | 0.129 ** | 0.429 ** | −0.179 ** | 0.665 ** | −0.244 ** | −0.185 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| J | Illegal Immigration | 0.481 ** | 0.033 | 0.008 | −0.336 ** | 0.581 ** | −0.437 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.417 ** | −0.267 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| K | Islamic Terrorism | 0.297 ** | 0.080 * | 0.022 | −0.208 ** | 0.437 ** | −0.249 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.294 ** | −0.127 ** | 0.600 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| L | Crime | 0.184 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.158 ** | −0.074 * | 0.404 ** | −0.136 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.010 | 0.502 ** | 0.505 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| M | Access to Healthcare | −0.328 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.562 ** | −0.256 ** | 0.439 ** | −0.176 ** | −0.185 ** | 0.386 ** | −0.244 ** | −0.170 ** | −0.017 | 1 | ||||||||

| N | Climate Change | −0.423 ** | 0.205 ** | 0.195 ** | 0.547 ** | −0.326 ** | 0.576 ** | −0.308 ** | −0.256 ** | 0.525 ** | −0.439 ** | −0.257 ** | −0.139 ** | 0.502 ** | 1 | |||||||

| O | Status Threat | 0.550 ** | −0.072 * | −0.061 | −0.363 ** | 0.701 ** | −0.598 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.483 ** | −0.381 ** | 0.628 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.358 ** | −0.302 ** | −0.422 ** | 1 | ||||||

| P | Conservative Media | 0.411 ** | −0.196 ** | −0.114 ** | −0.330 ** | 0.392 ** | −0.353 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.322 ** | −0.218 ** | 0.428 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.259 ** | −0.301 ** | −0.431 ** | 0.462 ** | 1 | |||||

| Q | Gender (Men = 1) | 0.141 ** | −0.085 * | −0.012 | −0.067 | 0.064 | −0.132 ** | 0.044 | 0.244 ** | −0.211 ** | 0.012 | −0.044 | −0.120 ** | −0.100 ** | −0.063 | 0.131 ** | 0.076 * | 1 | ||||

| R | Vote for Trump | 0.529 ** | −0.146 ** | −0.117 ** | −0.380 ** | 0.427 ** | −0.450 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.311 ** | −0.307 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.260 ** | −0.362 ** | −0.494 ** | 0.479 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.106 ** | 1 | |||

| S | Financial Situation | −0.187 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.273 ** | −0.124 ** | 0.150 ** | −0.011 | −0.045 | 0.068 | −0.107 ** | −0.103 ** | −0.077 * | 0.232 ** | 0.124 ** | −0.138 ** | −0.218 ** | −0.037 | −0.234 ** | 1 | ||

| T | Friends Affiliated with the Alt-Right | −0.214 ** | −0.029 | −0.068 | 0.050 | −0.008 | 0.127 ** | −0.132 ** | −0.023 | 0.141 ** | −0.111 ** | −0.045 | −0.008 | 0.067 | 0.092 * | −0.078 * | −0.066 | −0.121 ** | −0.087 * | −0.152 ** | 1 | |

| U | Social Dominance Orientation | 0.503 ** | −0.212 ** | −0.239 ** | −0.533 ** | 0.565 ** | −0.601 ** | 0.332 ** | 0.399 ** | −0.386 ** | 0.511 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.248 ** | −0.428 ** | −0.526 ** | 0.680 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.114 ** | 0.463 ** | −0.179 ** | −0.086 * | 1 |

| Mean | 0.58 | 5.50 | 5.29 | 4.95 | 3.71 | 3.89 | 4.81 | 3.19 | 3.84 | 4.95 | 5.21 | 5.01 | 5.06 | 4.39 | 4.23 | 35.22 | .60 | .55 | 2.46 | 4.44 | 3.27 | |

| Standard Deviation | .49 | 1.53 | 1.72 | 1.94 | 2.08 | 1.92 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 1.82 | 1.90 | 1.77 | 1.55 | 1.77 | 2.14 | 1.74 | 25.13 | .49 | .50 | .74 | 1.51 | 1.70 | |

| Minimum | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 100 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Perceived Social Problems with… | ||||||

| Government Corruption | −0.02 | 0.03 | <0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Washington Elites | <0.00 | 0.03 | <0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Wealth Gap | 0.05 ^ | 0.03 | 0.05 ^ | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Discrimination Against Whites | 0.33 ** | 0.03 | 0.33 ** | 0.03 | 0.38 ** | 0.05 |

| Discrimination Against Blacks | −0.23 ** | 0.03 | −0.22 ** | 0.03 | −0.23 ** | 0.05 |

| Political Correctness | 0.05 ^ | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Discrimination Against Men | 0.01 | 0.03 | <0.00 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Discrimination Against Women | −0.06 ^ | 0.03 | −0.06 * | 0.03 | −0.16 ** | 0.05 |

| Illegal Immigration | 0.18 ** | 0.03 | 0.18 ** | 0.03 | 0.16 ** | 0.05 |

| Islamic Terrorism | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.07 ^ | 0.04 |

| Crime | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Access to Healthcare | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Climate Change | 0.06 * | 0.02 | 0.08 ** | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Conservative Media | --- | --- | 0.10 ** | >0.00 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Government Corruption X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.12 | >0.00 |

| Washington Elites X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.06 | >0.00 |

| Wealth Gap X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.04 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Whites X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.10 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Blacks X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.02 | >0.00 |

| Political Correctness X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.07 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Men X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.11 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Women X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.16 * | >0.00 |

| Illegal Immigration X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | <0.00 | >0.00 |

| Islamic Terrorism X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.19 ^ | >0.00 |

| Crime X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.04 | >0.00 |

| Access to Healthcare X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.09 | >0.00 |

| Climate Change X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.17 ** | >0.00 |

| Controls | ||||||

| Gender | 0.04 ^ | 0.08 | 0.04 ^ | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Vote for Trump | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.10 | >0.00 | 0.09 |

| Financial Situation | <0.00 | 0.05 | >0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Friends Affiliated with the Alt-Right | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Social Dominance Orientation | 0.27 ** | 0.03 | 0.27 ** | 0.03 | 0.27 ** | 0.03 |

| F | 890.31 ** | 870.27 ** | 540.94 ** | |||

| R2 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.71 | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE |

| Perceived Social Problems with… | ||||||||

| Government Corruption | 0.99 | 0.09 | 1.01 | 0.09 | 1.02 | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.14 |

| Washington Elites | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 1.11 | 0.19 |

| Wealth Gap | 1.05 | 0.09 | 1.03 | 0.08 | 1.03 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.15 |

| Discrimination Against Whites | 1.47 ** | 0.12 | 1.36 ** | 0.12 | 1.36 ** | 0.12 | 1.81 ** | 0.29 |

| Discrimination Against Blacks | 0.84 * | 0.07 | 0.9 | 0.08 | 0.9 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.12 |

| Political Correctness | 1.13 ^ | 0.08 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 1.26 ^ | 0.16 |

| Discrimination Against Men | 1.04 | 0.08 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 1.04 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.13 |

| Discrimination Against Women | 1.11 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.09 | 1.12 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.17 |

| Illegal Immigration | 1.19 * | 0.1 | 1.14 | 0.1 | 1.14 | 0.1 | 1.17 | 0.18 |

| Islamic Terrorism | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.12 |

| Crime | 0.84 * | 0.07 | 0.83 * | 0.07 | 0.83 * | 0.07 | 0.84 | 0.12 |

| Access to Healthcare | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.14 |

| Climate Change | 0.87 ^ | 0.06 | 0.85 * | 0.06 | 0.87 * | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.12 |

| Status Threat | --- | --- | 1.38 ** | 0.14 | 1.35 ** | 0.14 | 1.32 ** | 0.14 |

| Conservative Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.02 |

| Government Corruption X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.01 ^ | >0.00 |

| Washington Elites X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Wealth Gap X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Whites X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.99 * | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Blacks X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Political Correctness X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Men X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Discrimination Against Women X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Illegal Immigration X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Islamic Terrorism X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.01 ^ | >0.00 |

| Crime X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Access to Healthcare X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Climate Change X Media | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | >0.00 |

| Controls | ||||||||

| Gender | 1.35 | 0.31 | 1.31 | 0.3 | 1.31 | 0.3 | 1.36 | 0.32 |

| Vote for Trump | 3.03 ** | 0.72 | 2.98 ** | 0.71 | 2.79 ** | 0.68 | 2.73 ** | 0.68 |

| Financial Situation | 0.62 ** | 0.1 | 0.62 ** | 0.1 | 0.64 ** | 0.1 | 0.63 ** | 0.1 |

| Friends Affiliated with the Alt-Right | 0.66 ** | 0.05 | 0.65 ** | 0.05 | 0.65 ** | 0.05 | 0.65 ** | 0.05 |

| Social Dominance Orientation | 1.27 ** | 0.12 | 1.16 | 0.11 | 1.16 | 0.11 | 1.17 | 0.11 |

| Log Likelihood | −296.39 | −291.52 | −290.73 | −282.97 | ||||

| Likelihood Ratio χ2 | 432.84 ** | 442.58 ** | 444.16 ** | 459.68 ** | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isom, D.A.; Boehme, H.M.; Mikell, T.C.; Chicoine, S.; Renner, M. Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right. Societies 2021, 11, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030072

Isom DA, Boehme HM, Mikell TC, Chicoine S, Renner M. Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right. Societies. 2021; 11(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsom, Deena A., Hunter M. Boehme, Toniqua C. Mikell, Stephen Chicoine, and Marion Renner. 2021. "Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right" Societies 11, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030072

APA StyleIsom, D. A., Boehme, H. M., Mikell, T. C., Chicoine, S., & Renner, M. (2021). Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right. Societies, 11(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030072