“System Conditions”, System Failure, Structural Racism and Anti-Racism in the United Kingdom: Evidence from Education and Beyond

Abstract

1. Introduction

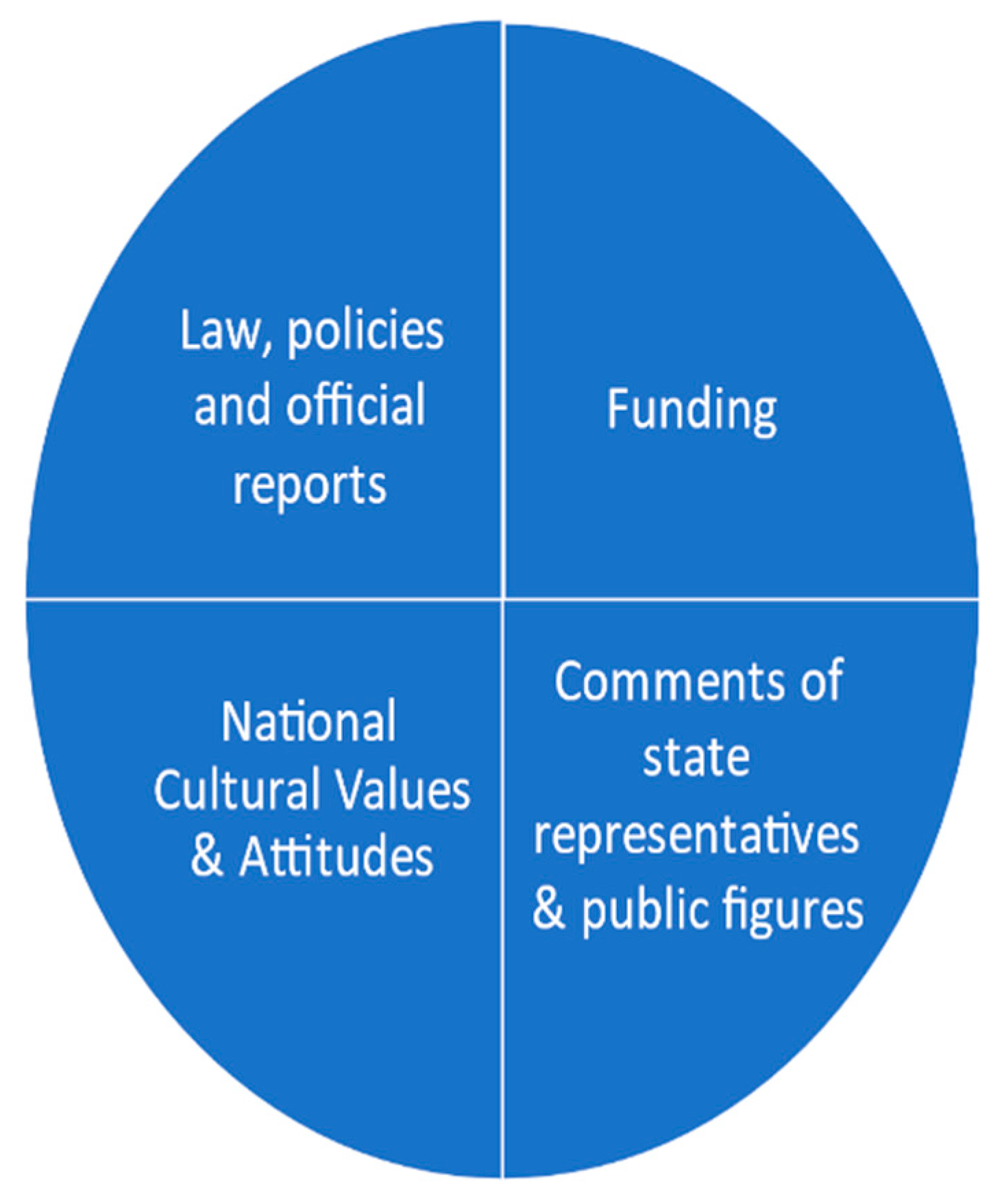

2. Conceptualising Racism and Anti-Racism

3. “System Conditions”

3.1. The Law, Policies and Official Reports

3.1.1. Overseas Trained Teachers (OTTs)

3.1.2. Teachers of BAME Heritage

3.1.3. The Sewell Report

3.2. Statements of State Representatives and Public Figures

3.2.1. Kemi Badenoch—Critical Race Theory

Our curriculum does not need to be decolonised, for the simple reason that it is not colonised. We should not apologise for the fact that British children primarily study the history of these islands. It goes without saying that the recent fad to decolonise maths, decolonise engineering and decolonise the sciences that we have seen across our universities—to make race the defining principle of what is studied—is not just misguided but actively opposed to the fundamental purpose of education. The curriculum, by its very nature, is limited; there are a finite number of hours to teach any subject. What we have not heard in this debate, from honourable Members on both sides of the House who want more added to it, is what must necessarily be taken out....

Of course black lives matter, but we know that the Black Lives Matter movement is political. I know that because, at the height of the protests, I have been told of white Black Lives Matter protesters calling a black armed police officer guarding Downing Street—I apologise for saying this word—“a pet nigger”. That is why we do not endorse that movement on this side of the House. It is a political movement. It would be nice if Opposition Members condemned many of the actions of that political movement, instead of pretending that it is a completely wholesome anti-racist organisation.

Lots of pernicious stuff is being pushed, and we stand against that. We do not want teachers to teach their white pupils about white privilege and inherited racial guilt. Let me be clear that any school that teaches those elements of critical race theory as fact, or that promotes partisan political views such as defunding the police without offering a balanced treatment of opposing views, is breaking the law….

Why does this issue mean so much to me? It is not just because I am a first-generation immigrant. It is because my daughter came home from school this month and said to me, “We’re learning Black History Month because every other month is about white history”. That is wrong and it is not what our children should be picking up. Those are not the values that I have taught her. They are yet another sign of the pernicious identity politics that look at individuals primarily as groups of biological characteristics. People often do not realise when that has taken hold, and I know that many of them are well meaning…. History tells us that this is a country that welcomes people, and that black people from all over the world have found this to be a great and welcoming country [11].

3.2.2. Liz Truss—The New Fight for Fairness

3.2.3. Laurence Fox—The Duchess of Sussex and Sikhs

3.2.4. Eamon Holmes—The Duchess of Sussex

3.2.5. Boris Johnson—Black People and Muslims

3.3. National Cultural Values and Attitudes

- democracy;

- the rule of law;

- individual liberty;

- mutual respect;

- tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs and for those without faith.

- “respond to the ideological challenge of terrorism and the threat faced from those who promote it”;

- “prevent people from being drawn into terrorism and ensure that they are given appropriate advice and support”;

- “work with sectors and institutions where there are risks of radicalisation”

3.4. Funding

4. System Conditions, Structural Racism and Anti-Racism

5. System Conditions, System Failure

- The political system adopts a different set of values and expectations to institutions;

- There are clashes in goals pursued within the system;

- Constructive forces of change meet conservative forces against change;

- The system continues to promote strong kinship and ethnic affinities and disregard the larger umbrella system [42] (p. 14).

6. Concluding Thoughts

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, P. ‘White sanction’, institutional, group and individual interaction in the promotion and progression of black and minority ethnic academics and teachers in England. Power Educ. 2016, 8, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusoga, D. Britain Is nNACot America. But We too Are Disfigured by Deep and Pervasive Racism. 7 June 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/07/britain-is-not-america-but-we-too-are-disfigured-by-deep-and-pervasive-racism (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- MacPherson, W. The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report. 24 February 1999. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-stephen-lawrence-inquiry (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- NAC International Perspectives: Women and Global Solidarity. Anti-Racism Defined. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20201101022553/http://www.aclrc.com/antiracism-defined (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Lewis, G. ‘Race’, Gender, Social Welfare: Encounters in a Postcolonial Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.; O’Donovan, B. System Conditions: A Powerful Lever for Change. Available online: https://vanguard-method.net/2016/10/system-conditions-a-powerful-lever-for-change/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Department for Education. Guidance: Qualified Teacher sTatus (QTS): Qualify to Teach in England. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/qualified-teacher-status-qts (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Miller, P. Aspiration, career progression and Overseas Trained Teachers (OTTs) in England. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2018, 22, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. ‘Tackling’ race inequality in school leadership: Positive actions in BAME teacher progression – evidence from three English schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 48, 986–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Government. Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report. 31 March 2021. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/974507/20210331_-_CRED_Report_-_FINAL_-_Web_Accessible.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Hansard. Black History Month—Volume 682: Debated on Tuesday 20 October 2020—UK Parliament. 20 October 2020. Available online: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2020-10-20/debates/5B0E393E-8778-4973-B318-C17797DFBB22/BlackHistoryMonth (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Truss, L. ‘Fight for Fairness’ Speech Sets out Government’s New Approach to Equality. 17 December 2020. Available online: https://www.fenews.co.uk/fevoices/60682-press-release-fight-for-fairness-speech-to-set-out-governments-new-approach-to-equality (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Webber, A. Civil Service Unconscious Bias Training to Be Scrapped. 15 December 2020. Available online: https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/civil-service-unconscious-bias-training-to-be-scrapped/ (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- BBC. Laurence Fox Apologises to Sikhs for ‘clumsy’ 1917 Comments. 24 January 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-51233734 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Grater, T. ‘White Lines’ Actor Laurence Fox Dropped by Agency after Racism Row. 13 November 2020. Available online: https://deadline.com/2020/11/laurence-fox-dropped-agency-racism-row-1234615190/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Bray, A. Eamonn Holmes in Race Row Over Calling Meghan Markle Uppity. 24 November 2019. Available online: https://metro.co.uk/2019/11/24/eamonn-holmes-race-row-questioned-calling-meghan-markle-uppity-itv-ban-word-11208230/?ito=cbshare (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Weatherby, B. Eamonn Holmes Calls Meghan Markle ‘Spoilt, Weak, Woke and Manipulative’ in Scathing Rant. 10 January 2020. Available online: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/eamonn-holmes-meghan-markle-royals-sussex-a4331791.html (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Johnson, B. The Boris Archive: Africa Is a Mess, but We can’t Blame Colonialism. 2 February 2002. Available online: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-boris-archive-africa-is-a-mess-but-we-can-t-blame-colonialism (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Johnson, B. Don’t Just Call it War. 16 July 2005. Available online: http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/16th-july-2005/12/just-dont-call-it-war (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Bienkov, A. Boris Johnson Called Gay Men ‘Tank-Topped Bumboys’ and Black People ‘Piccaninnies’ with ‘Watermelon Smiles’. Insider. 9 June 2020. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/boris-johnson-record-sexist-homophobic-and-racist-comments-bumboys-piccaninnies-2019-6?r=US&IR=T (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- BBC. Boris Johnson Faces Criticism over Burka ‘Letter Box’ Jibe. 6 August 2018. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-45083275 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Ofsted. School Inspection Handbook. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspection-handbook-from-september-2015 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- HM Government. Prevent Strategy. 7 June 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prevent-strategy-2011 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Department for Education. Press Release: Guidance on Promoting British Values in Schools Published. 27 November 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/guidance-on-promoting-british-values-in-schools-published (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Thomas, P. Britain’s Prevent Strategy: Always Changing, Always the Same? In The Prevent Duty in Education; Blusher, J., Jerome, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hechter, M.; Horne, C. Theories of Social Order: A Reader; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. Minister Fails to Condemn Millwall Fans who Booed Players Taking a Knee. 6 December 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/06/millwall-fans-who-booed-players-taking-a-knee-should-be-respected-says-eustice (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- The Times. (Dozens of Tory MPs Set to Refuse Unconscious Bias Training. 21 September 2020. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/dozens-of-tory-mps-set-to-refuse-unconscious-bias-training-sfnrm895g (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Burns, J. Universities ‘oblivious’ to Campus Racial Abuse. 23 October 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-50123697 (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Department for Education. Leadership Equality and Diversity Fund: For School-Led Programmes. Available online: http://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-and-diversity-funding-for-school-led-projects (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Department for Education. Statement of Intent on the Diversity of the Teaching Workforce—Setting the Case for a Diverse Teaching Workforce. October 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/747586/Statement_of_intent_on_the_diversity_of_the_teaching_workforce.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Carr, J. ‘Disgraceful’: DfE Axes Funding for Teacher Diversity Schemes. 20 November 2019. Available online: https://schoolsweek.co.uk/disgraceful-dfe-axes-funding-for-teacher-diversity-schemes/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Whitaker, R. Canadian Immigration Policy since Confederation; Canadian Historical Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. Overseas Trained Teachers: Departmental Advice for Overseas Trained Teachers, Local Authorities, Maintained Schools and Governing Bodies. April 2013. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/15171416.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Ward, T. Critical Education Theory: Education and State, Part 1, 2006. Available online: http://www.tonywardedu.com/images/critical_theory/critical%20education%20part.1.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk; Bedford Books; Yale University Press: London UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Picower, B. The unexamined whiteness of teaching: How white teachers maintain and enact dominant racial ideologies. Race Ethn. Educ. 2009, 12, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, J.; Stewart, L. System Failure Analysis: A Fault-Tree-Driven, Disciplined Failure Analysis Approach. In Proceedings of the Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium, Upland, CA, USA, 22–24 January 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. Political Science. In The International Encyclopaedia of Social Sciences; Macmillan Ltd.: Basingstoke, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rotberg, R. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Juma, T.; Oluoch, K. System Failure Causes of Conflict in Africa as a Social Transformation. Int. Aff. Glob. Strategy 2013, 17, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See for example: (1) Kenneth Little. Negroes in Britain: A Study of Racial Relations in English Society, London, Kegan Paul, 1948; (2) James Wickenden. Colour in Britain, Oxford University Press/Institute for Race Relations, 1958; (3) Rampton Report- West Indian Children in Our Schools, 1981; (4) Paul Gilroy. The Empire Strikes Back: Race and racism in 70s Britain, London, Hutchinson, 1982; (5) The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report/Macpherson report, 1991; (6) The Lammy Review, 2017; (7) Race in the workplace: The McGregor-Smith Review, 2017; (8) Race Disparity Audit, 2017; Paul Miller and Christine Callender. Race, Education & Educational Leadership in England: An Integrated Analysis, London, Bloomsbury, 2019. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miller, P. “System Conditions”, System Failure, Structural Racism and Anti-Racism in the United Kingdom: Evidence from Education and Beyond. Societies 2021, 11, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020042

Miller P. “System Conditions”, System Failure, Structural Racism and Anti-Racism in the United Kingdom: Evidence from Education and Beyond. Societies. 2021; 11(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiller, Paul. 2021. "“System Conditions”, System Failure, Structural Racism and Anti-Racism in the United Kingdom: Evidence from Education and Beyond" Societies 11, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020042

APA StyleMiller, P. (2021). “System Conditions”, System Failure, Structural Racism and Anti-Racism in the United Kingdom: Evidence from Education and Beyond. Societies, 11(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020042