Abstract

Children’s participation in planning has been investigated to some extent. There are, however, unexplored topics, particularly concerning what is needed for children’s participation to become a regular process. Based on case studies in Sweden, this article draws some conclusions. It is quite possible to organize ordinary processes where children participate in community building, in collaboration with planners, as part of their schoolwork. The key question is how this can be done. Clearly, it needs to occur in close collaboration with teachers and pupils, however it also needs to be implemented in a system-challenging manner. Thus, rather than looking for tools with potential to work in the existing school and planners’ world, it is important to design research that aims to create learning processes that have the potential to change praxis. Hence, it is not the case that tools are not needed, rather that children need to help to develop them.

1. Introduction

Ever since “Our common future” and “Agenda 21” were written thirty years ago, there has been global agreement on the need for increased citizen participation in planning and community transformation, the aim being to achieve the goals of sustainable development. Yet, in practice, attempts to realize these visions have been slow. Children’s participation has been reinforced by the increasing importance of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). In Sweden, it will even become law in 2020. Although children’s perspectives and rights to participate in planning and community building have been explored, practices have not changed significantly thus far. At present, in 2020, it looks as though a change can be discerned, in that young people such as in the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg’s school strike, the Pakistani activist Malala Yousefzai’s fight for girls’ right to go to school, and the American activist Emma González’ youth protest movement against gun violence, have had global repercussions. Children and youth are coming together in the common belief that adults are not assuming sufficient responsibility for human survival on earth. However, what does it mean in practice for children and youth to influence developments? The present article examines a section of this interesting question, aiming to understand more about the prerequisites for implementing children’s participation in the broader area of physical planning. In this article, by “planning” we mean urban development in a broad sense, including concrete planning instruments as well as, e.g., investigations about where densification should be implemented, or where adventure parks for children should be built.

2. State-of-the-Art

The “participatory turn” in planning has its roots in the 1960s with advocacy planning [1], which in turn had its background in the US [2] and, furthermore, existed as a model for developing democracy in Europe [3]. After a fairly long period of disinterest, the participatory turn has essentially developed into a movement in Europe [4]. One reason for this is related to rapid global social and environmental changes. Complex and wicked problems require the development of new theory and practices of collaborative rationality [5]. Another view is related to the reconsideration of roles. If planning cannot be seen as value neutral [6], then invisible agendas for planning practices need to be unfolded and reconstructed [7] based on analyses of class, race, gender, ethnic, or ideological biases [8]. A third view is related to justice and resilience [9]. When, faced with changing global financial circumstances and climate change, governments fail to deal with urbanization processes, community management may be considered an answer [10]. In this view, multicultural cities want approaches other than to be run as businesses; they need to be planned on the basis of equity and human needs, where citizens are not only thought of as consumers [11]. In reality, however, cities are criticized for unilaterally investing in just one community group:

While much urban development is designed to attract the ‘creative class,’ Millennials, and homeowners without children, the percentage of families with children in cities is growing in the United States (Florida 2011; Phillips 2013). Families and children are among the least heard or considered in new urban developments. Prominent journalists have questioned whether children belong in cities (DePillis 2014), suggesting instead that cities should cater to younger, well-educated adults with ‘healthy incomes’ who can support urban development and economic growth[12] (31)

The question of children’s participation in planning has been investigated to some extent [13]. There is an idea that what is good for children is good for all:

Successful cities are cities where children of all ages are active and visible in the public realm. The amount of time children spend playing outdoors, their ability to get around independently and their level of contact with nature are strong indicators of how successfully a city is performing, not just for children but for everyone[14] (65)

In her research, Freeman expressed disappointment about not being able, as part of the academic realm, to influence planning so as to improve the lives of children living in urban environments [15]. Some research has recognized children as competent knowledge-builders in society, but this is not widespread [16].

This also applies to Sweden. For instance, children transferring their knowledge about the local area to GIS-based systems that planners use has been successfully tested. This helps planners “hear children”; however, most initiatives do not aim high with regard to children’s influence [17]. Research in Finland on using GIS tools such as Maptionnaire has found that, due to planners’ lack of knowledge and motivation, there is still a long way to go before such experiments can lead to a well-functioning ordinary process [18]. Such research, however, is in line with researchers who believe that digital tools should be adapted to planners’ systems if they are to be of value to society; hence, these tools should not be system-challenging.

One common thread in articles on this topic is that they have often started from Arnstein’s ladder of participation [19]—noting the frequent occurrences of manipulation, decoration and tokenism when children are invited to participate—and Hart’s [20] post-criticism of and reflection on his own analysis of the ladder [21]. Moreover, they have frequently concluded by calling for a new generation of models on children’s participation, sometimes even going so far as to abandon the idea of models, given that they tend to be used hastily and incorrectly:

What is now needed are programs of collaboration between academics and those who work directly with children as well as with children and youth themselves. In particular we need to find ways of monitoring and evaluating the way that we work with children and the quality of the realisation of their participation rights[20] (29)

One could say that it is possible to discern three main streams of research on children’s participation. One stream concerns what children’s participation really means [22]. Does it only occur when children themselves participate in planning, or also when knowledgeable adults bring children’s perspectives into the planning process? The second stream is interested in children’s knowledge and is critical of the mainstream notion that young people are not sufficiently competent to affect planning [23]. The current actions of Greta Thunberg have shed more light on that notion. The third stream places participation in a community context and examines what is needed for children’s participation to become a regular process, what system changes are needed to make participation lasting [24].

There are unexplored topics in all three streams of research, however the third points out a particularly important knowledge gap that the present article is trying to fill. The article mainly concerns two spheres in society: the city planning office and compulsory school,1 the former because they are responsible for planning processes in the city and the latter because compulsory schools need to be involved if these efforts are to reach the children on a regular basis. Reaching them through leisure activities is also possible, and such projects have been carried out to a large extent. However, only a certain segment of children are reached in this way, which becomes a problem of democracy. In addition, there are no similar fixed structures in all leisure activities where children’s participation can be incorporated. For this reason, such activities frequently become experiments that are not automatically repeated.

The present article therefore seeks to generate knowledge concerning how planners and school children can carry out a dialogue about planning and do so as an ordinary part of the planning process. How can we create conditions for school children’s participation in urban transformation processes, and in such a way that their knowledge, experience, and views actually influence the content of planning?

3. The Context

Sweden, like the rest of the world, is moving towards a new liberal economy that is market- and profit-oriented, competitive, and pushes privatization into the public sector, with a focus on shareholder interests [25]. Sweden also has a long tradition of child-friendly environments and, according to Cele, although children have a rather strong position in the society, it is still very much “based on a normative and adultist view” [26] (16). With UNCRC becoming law, this is expected to change radically as it is now possible to hold local authorities legally accountable if they do not follow the convention. While ratification was a moral obligation, now it can provide consequences. UNCRC may also clash with other legislation, which entails the need to develop new practices.

Simultaneously, the City of Gothenburg is currently undergoing a centralization process. In 2019, in line with new public management approaches [27], the responsibility for compulsory schools was centralized to the municipality from the districts, and the 10 districts are expected to be closed down in 2020. This is a radical change, because today the districts have responsibility for the social welfare of residents and are also responsible for overall citizen dialogue. Thus, at the same time as the UNCRC is becoming law, a major reorganization is taking place in the municipality that diminishes local power.

The planning authorities in Gothenburg are placed centrally at the City Planning Office and are responsible for dialogue with other centrally located administrative offices in connection with planning. The difference between these offices is that only the City Planning Office is responsible for consulting the residents when planning. This takes place when detailed plans are made, in a controlled manner specified in the Plan and Building Act. This procedure is often highlighted as an example of the well-developed citizen dialogue in planning found in Sweden. It has, however, been heavily criticized in research for being too late in the process to have any significance, and in addition, the residents’ resentments and attempts are almost always overlooked by planners [6,28]. This problem is even more complex in relation to stigmatized neighborhoods [29] in the outskirts of the larger cities. These neighborhoods have many immigrant residents and they already experience a so-called democratic deficit due to low voter turnout [30]. That is partly why the government acknowledged the need to develop representative democracy with more participation [31].

In line with this, the City Planning Office in Gothenburg is striving for increased citizen participation, in general, and for improved dialogue with children, in particular. To ensure changed practices in the municipality, city officials have developed two tools that are to be applied in all planning situations: child impact assessment and social impact assessment [32,33]. The tools are being used, but this is also receiving some criticism, as the tools are largely used by civil servants who are trying to imagine children’s needs, and too little asking the children directly. Thus, according to an interview with planners as part of the present research, the tools themselves are good, but the failure is connected to how they are applied. Municipal officials want more of the evaluations to be conducted by talking with children. The municipality thus saw a need to generate knowledge about this which was the basis for their interest in collaborating with us on conducting the present research.

4. Empirical Material and Method of Investigation

The research project underlying the present article was called “children as co-creators of the urban space”. The neighborhood we chose to work with was Hammarkullen in the outskirts of Gothenburg, an area built in the 1960s. We have worked with research and higher education in this neighborhood for many years, and therefore have a trusting relationship with a compulsory school. The area is vibrant, including a large number of political activities and an active cultural life run by associations. At the same time, due to the spatial segregation of immigrants, it is often branded—by the media, academics, municipal employees, and the community—as “peripheral” and “different”, and attributed a “territorial stigma” [34]. Today, Sweden is also suffering from a somewhat acute education problem related to housing segregation and liberalization of the schools: a significantly larger proportion of pupils in compulsory school in stigmatized suburban centers in Sweden (occasionally as high as 70%) fail in a core subject (mathematics, Swedish, English) and cannot therefore start upper secondary school. Connected to these difficulties, fast changes are taking place in society that are leading to a weakened public sector, which makes it problematic to deal with the complex challenges posed by the present organizational constructions and strained economic circumstances.

The school we worked with in this area—Nytorpskolan—has just over 400 pupils in the age range 12–15 years and is run by the municipality. Three teachers at the school got involved in the project. Based on the aim of the research project, researchers and teachers at the school gradually designed three case studies over a three-year period: (1) pupils’ choice; (2) child impact assessment; and (3) work experience.

The project employed an action-oriented [35] transdisciplinary research methodology [36], including an action planning approach [37], and methods used in the empirical analysis included content and thematic analysis [38]. Besides traditional desk reviews, the research draws on case studies explored through document studies, participant observation, and interviews [39].

The parents of the participating children were asked in writing via the teachers about consent for the children’s participation in the research project. The children were in addition asked by one of the teachers about the use of their quotes in this article and in connection with that a question of anonymity came up. The children wanted to appear by name in the quotes, as they felt proud to fight for changing the majority society’s view of their neighborhood and themselves. We still chose not to publish their names, because we think they (nor we) cannot foresee any negative consequences for them in the future. To meet the children’s desire of openness to some extent, we chose, with the support of the teachers, to publish the school’s name. Publishing the school’s name also has a research interest as context plays a major role; schools have different conditions depending on, e.g., form of ownership.

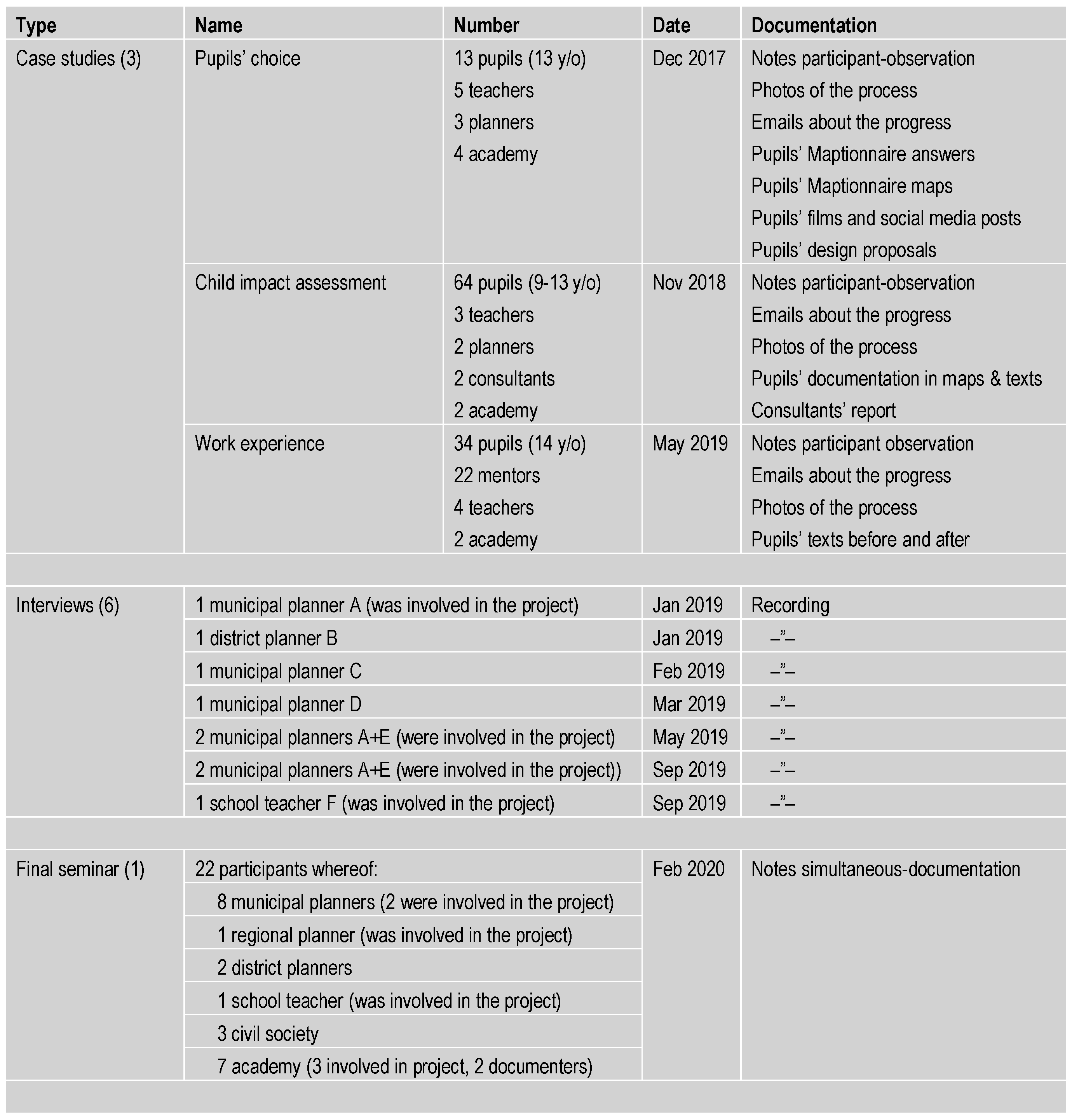

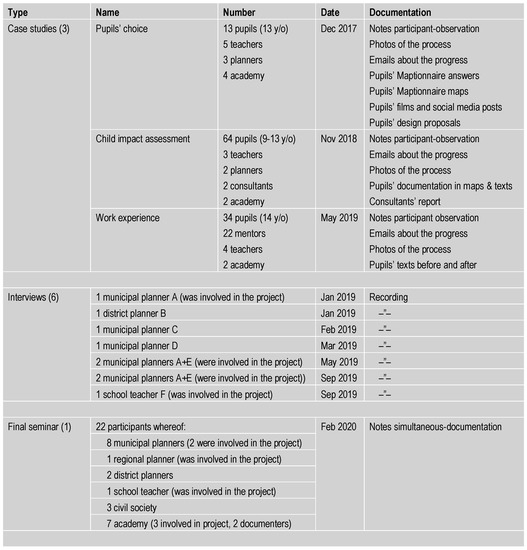

The case studies have been documented in text, photos, pictures, and audio-recordings of interviews with key persons (see Figure 1). At the end of the project, an open seminar was held where the case studies and analysis results were presented and discussed. The participants were largely civil servants from the municipality, but also academics and residents from civil society. The final seminar was documented and the discussion was included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Picture of the project’s empirical material.

5. Children’s Participation—Theoretical Framework for Analysis

There are hopeful reports in the research. Derr presents experiences from Boulder in the United States, one of few cities that succeeded in institutionalizing youth participation in planning through implementation of a model for integrating the student role and the citizen role on a regular basis [12] (31). Most research, however, is quite critical of the fact that the effect of children’s participation is unsatisfactory. These criticisms indicate that few system-changing activities exist that are related to children’s participation in planning. For this reason, the work children do to contribute their knowledge and views often, for various reasons, does not play a role in planning in the long run. In her extensive review, Freeman is very critical:

I began this Viewpoint by asking ‘has research in children’s geographies contributed to an improvement in children’s lives over the last 25 years’. The answer would have to be Not really, in the sense that so many children’s lives continue to be precarious[15] (119)

Concerning the Swedish context, Cele and van der Burgt expressed the same criticism with particular clarity:

We argue that while Swedish children have a strong position in society, they are excluded from planning processes due to the rigidity of the planning process, neoliberal influences and planners’ lack of competence[26] (14)

We have therefore sought knowledge about why the situation looks like this, and to this end we have looked both at the school world and the sphere of planners. Hence, we have, by including this knowledge in our analytical framework, tried to understand more about the aforementioned “rigidity of the planning process, neoliberal influences and planners’ lack of competence” by carrying out research work in collaboration with planners, but we have also assumed that the same criticism can apply to the world of the school, and this is why we have also conducted research together with teachers and children. Actually, previous research shows that one of the main “systems” in use in schools—textbooks—teaches a view on democracy that is outdated, and this affects pupils’ identity formation:

Thus, the overall conclusion is that textbooks enact a certain conflict between means and ends. While the end is the reproduction of liberal democracy and liberal, individual citizenship, pupils are requested to transform themselves into supporters of contemporary Swedish democracy, positioning them as not-yet-citizens and not-yet political subjects[10] (2)

These reflections on children’s participation are not particularly hopeful, but they do contribute knowledge to an analytical framework that is critical of participatory forms that lock children into outdated structures, or even worse, that reinforce exclusion that is already severe for children growing up in so-called vulnerable neighborhoods.

What has been helpful for our analytical framework is clarifying discussions about the three generally accepted explanations for why children are invited to participate, thus legitimate reasons for participation: (a) children have competencies and knowledge that planning should incorporate; (b) there is educational value in participation-learning-by-doing; and (c) participation empowers children in relation to adults and encourages them to become community builders [40] (15).

What the critical academic voices have in common is an interest in children’s identity formation, which is related to the preferential right of interpretation regarding how a place of residence is described. In this context, age discrimination is interesting:

There was an underlying understanding of competency as defined from an adult definition of planning competencies, which, in turn, made it problematic to see children as competent social actors in the planning process. This illustrates how the participants are part of a planning system that clearly has an understanding of children as incompetent in the planning process[40] (21)

These voices have also looked at children’s participation from a social perspective, arguing that the high degree of neoliberal influence on planning renders children’s own influence even more important to develop, as neoliberalism reduces authorities’ influence, and there is now little time for civil servants to protect the most vulnerable in society [25,41].

Concerning the world of the school, it has also been affected by neoliberalization. Allelin [42] described the change the Swedish school system has undergone during the past 30 years as a shift from a school focused on the acquisition of knowledge, community, and the school’s compensatory assignment to a focus on detailed accounting of what can easily be measured, with a narrow focus on individual subjects and grades.

To sum up, our analytical framework has consisted of the mentioned theoretical perspectives, not forgetting the system-critical angle that was taken up by Freeman initially [15].

6. Results—Three Case Studies to Learn from

The three case studies were different in terms of power. The first was designed on the school’s terms and in collaboration with the central municipality. The second was designed on the municipality’s terms and in collaboration with three compulsory schools in Hammarkullen. The third was designed on the school’s terms and in collaboration with the local municipality.

6.1. Pupil’s Choice

“Pupil’s choice” is in the curriculum in all compulsory schools and aims to allow students to choose something they themselves want to learn about. On the basis of a selection given by the school, students devote five days to this teacher-led activity. In December of 2017, the research team and the teachers proposed an activity called “Map the Hill” (Hammarkullen means “hammer-hill”), which aimed to provide tools for the children to assess and describe their area themselves, thereby helping them to be or become community builders. Thirteen 13-year-old pupils chose our theme and worked with us in a concentrated manner for one week. The tool we taught them was Maptionnaire, which is an online GIS/map-based survey designed to glean ideas and insights from inhabitants [43]. Using the tool, inhabitants are to mark their opinions about different places on an aerial photo.

The questions in the survey were formed by the researchers and teachers in advance and modified during the process with the pupils. Mapping the area was carried out by the pupils, both in the school, where they used Maptionnaire on their tablets to interview other pupils, and while moving around, interviewing inhabitants they met and relatives. The aggregated results from all 117 interviews revealed heatmaps of “good” and “bad” places and paths, and people’s explanations for their opinions.

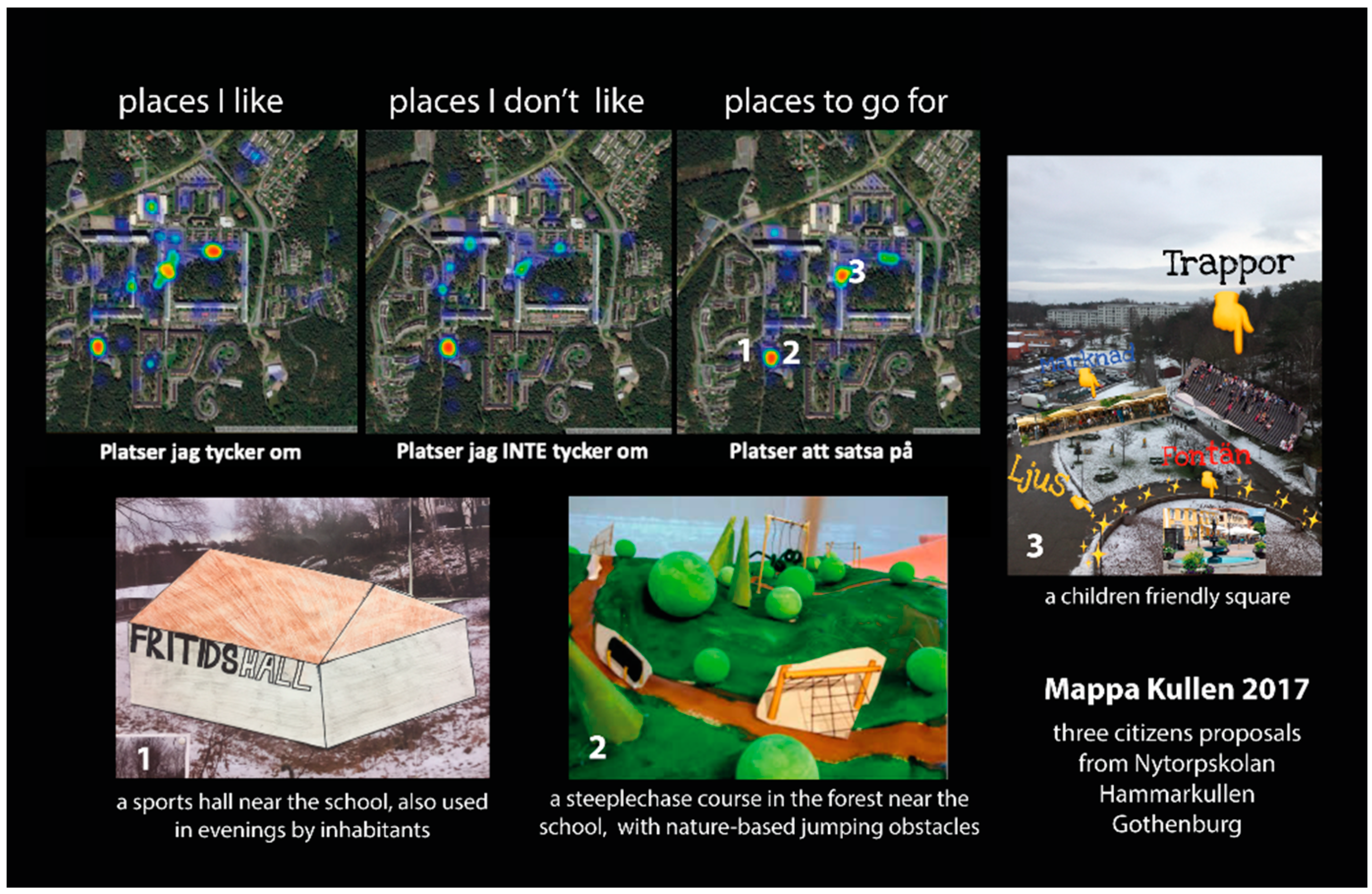

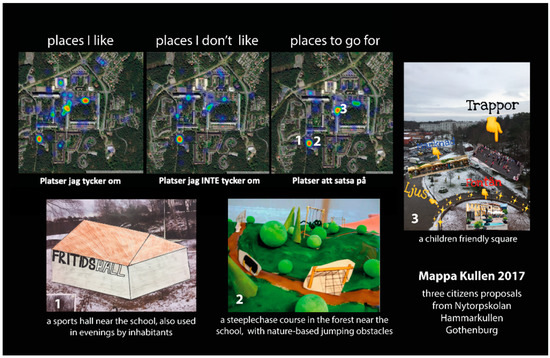

Based on that information, the pupils were tasked with proposing something for a place about which many opinions were given. They went to the three sites selected by most people, documented them with photos, and discussed them. In collaboration with their art teacher, they then designed something that would solve the problems noted, but without destroying the positive qualities mentioned about the same place. Thus, they worked in an interdisciplinary manner, involving several core subject teachers. The results were design proposals for: (1) a sports hall near the school, also used in evenings by inhabitants; (2) a steeplechase course in the forest near the school, with nature-based jumping obstacles; and (3) a child-friendly square (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The results of pupil’s choice.

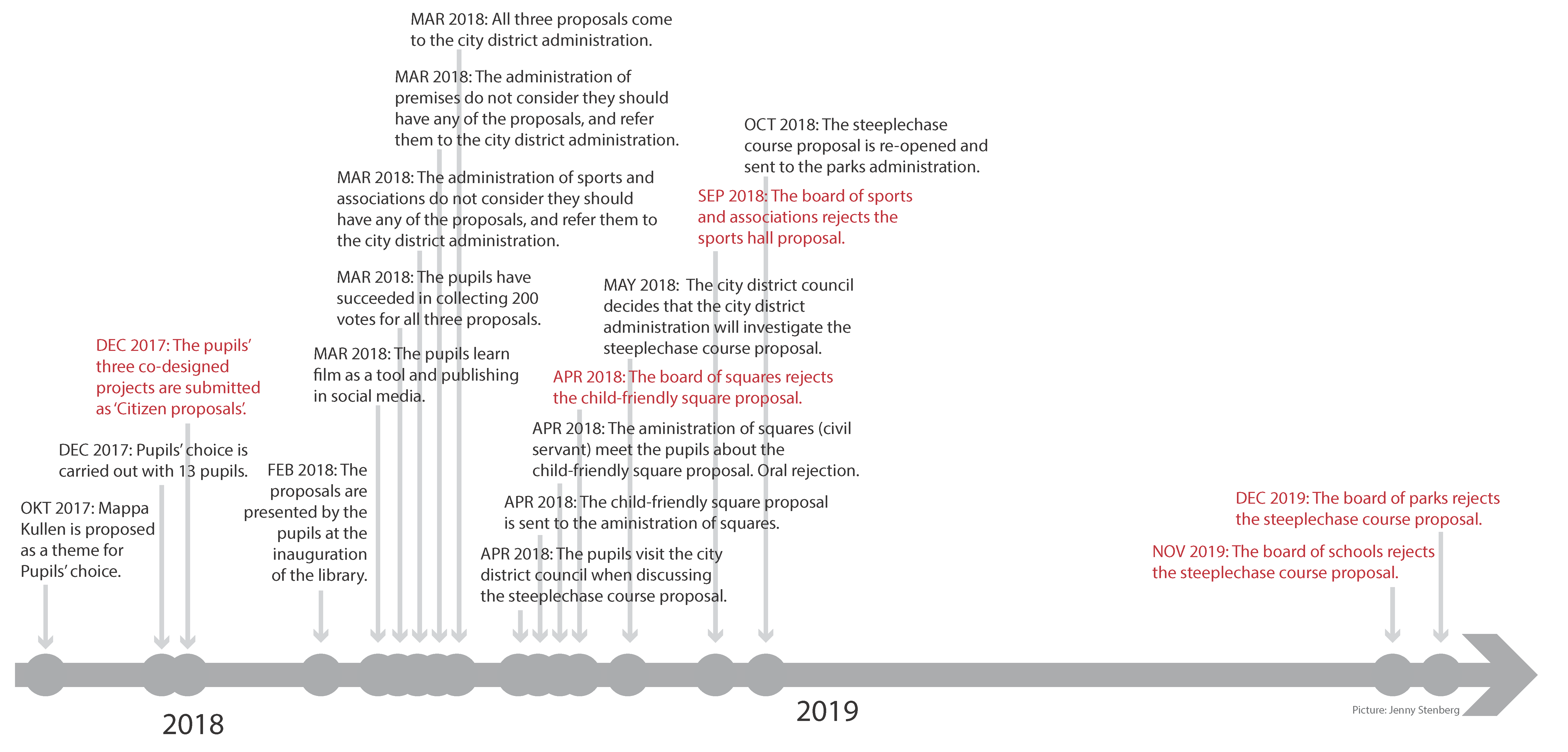

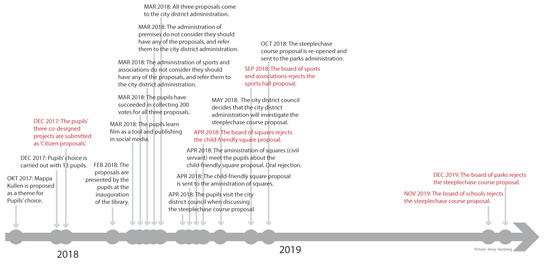

To make these results visible to planners, the proposals were submitted as “citizen proposals” in the existing proposal-reception system. Subsequently, pupil’s-choice week ended, but some of the teachers brought it into regular instruction to follow up on what had happened to the proposals. For politicians to consider a proposal, 200 votes are required. In social studies class, they mobilized for that to happen, and with support from the research team they learned filming techniques to reach out through social media. All three projects successively managed to collect 200 votes, and then the pupils followed how the proposals were handled. Among other things, a group of children listened when politicians discussed one of the pupils’ proposals in the district council. Two of the proposals were subsequently rejected, while the third (steeplechase course) was processed for two years and then rejected (see Figure 3). The rejections were also discussed in classes.

Figure 3.

The timeline of pupil’s choice.

There was a lot to learn from this case study. The first reflection concerns the reception of the ideas: the design proposals were not well handled by the municipality, despite being submitted using an existing municipal tool for citizens’ proposals. What we saw when following the process was a series of lack of qualities in systems and practices. Figuring out how to vote was very complicated, so much so that the pupils had to make instructional videos on YouTube to help parents and friends. The procedure for reception of proposals by the relevant administrations worked poorly, as it was not subordinate to the line organization and therefore had low priority. Moreover, citizens think about everyday life and leave proposals that by their very nature affect many different administrations, which administrations organized in “silos” have difficulty handling. Therefore, quite often an “automatic reflex” occurred in administrations, indicating that “this should be on someone else’s table”. These experiences are related to rigidity in the municipal organization and perhaps also lack of competence in managing citizen dialogues. What they did miss was of course children’s competencies and knowledge when they failed to seriously try to make their design proposals a reality. At a meeting where the children questioned the actual choice of design of the square, the responsible civil servant answered, rather bluntly, that they had actually asked the elderly in the square what they wanted. One of the children tried to reach out: “Why are you listening to them and not us?”, but without success; the civil servant ended that discussion by saying that the design of the square was already complete. The children looked abandoned, which was noted in participant observation. It is natural to agree with Cele’s and van der Burgt’s experience, that this “illustrates how the participants are part of a planning system that clearly has an understanding of children as incompetent” [26] (21). This means that densified spaces risk losing certain qualities, and spaces that are not addressed at all still have their problems.

What did work well in this case study was, however, how much the pupils actually learned. The project empowered them to become community builders, which was obvious when they attended the meeting when politicians discussed one of their proposals. The pupils were given much recognition there, and this created hope for the future. Hope, in turn, led to a willingness to present the project in other public contexts, e.g., a library exhibition, where they expressed pride for the work and their community. The work thus greatly contributed to their identity-building and effected their “place attachment” [44]. Moreover, their teachers felt the project provided important information for core school subjects. Obviously, actually getting their proposals through was satisfying for the pupils but learning how democracy works—or does not work—is also a very important part of being fostered to become community builders.

6.2. Child Impact Assessment

The City Planning Office of Gothenburg became interested in strategic planning for Hammarkullen because the stigmatized neighborhood—50 years after it was built—had finally begun to experience pressure from the market to build housing. This pressure was largely the result of the overall severe housing shortage in Sweden. Because there are many children in the area, it was particularly interesting for the municipality to develop the tool “child impact assessment” and to let children conduct the analysis themselves. The work took place in the autumn of 2018 and was linked to a current planning process. The assessment was thus carried out by the municipality, and the research team served an advisory role when the process was being formed. The municipality engaged an external consulting firm for the implementation work, and the research team followed that process. The consultants were part of a network of “architectural pedagogues” with which the authorities often collaborate.

All three compulsory schools in Hammarkullen were invited, and one class from each school agreed to participate. There was a total of 64 pupils, 9–13 years of age. The assessment was carried out in three steps with each class, resulting in a total of nine workshops with children. Basically, the children were asked to mark on maps places and paths they experience either positively or negatively. The second step was to walk to these places and, using signs from which they could choose, express the feelings they had for the places. The third step was to take the tram to the city center and visit the City Planning Office. In meetings with planners, the children told their stories and could also reflect on the compiled material in the form of texts and marked maps of Hammarkullen.

The planners then added these results to other information in the planning process for a new detailed plan of the square and other densification proposals that were currently being developed. The schools do not seem to have incorporated the experience into their core subject education. The children thus contributed their knowledge to the planning; however, they were not recognized as active citizens—neither in the world of planners nor in the school.

This case study was also an interesting learning experience for the research team. The first lesson was that it was much more difficult to get approval from the school when the project was designed to fit in with the systems of an external institution, which in this case was the City Planning Office. If children’s participation is to become an ordinary process, teachers must have more power to influence the process and school management must give them the mandate and time to participate. Without the resource of time, learning is sporadic and limited. Had they had the time and a mandate, the teachers could have done more to incorporate the project into the core subjects and developed a strategy for how the children themselves could have worked with formulating insights about all of the interesting themes the tool consists of. Such a mandate would have given teachers the opportunity to develop a new practice for the school, working with the children both as pupils and as active citizens in parallel.

One of the positive effects of this case study was how the material was received at the City Planning Office and the fact that, subsequently, the knowledge seemed to have been made use of in ongoing planning. In interviews, planners highlighted two such results that were formally included in considerations in September 2019 concerning a proposed site for new housing construction. One was that the children had pointed out the importance of not obstructing the path of the Hammarkullen Carnival that takes place annually, with around 40,000 visitors—an event that is an important part of the children’s identity formation. Another result was that the proposed site is on the children’s walkway to school. This means that the ground floor of the new building should be designed with care so that the children can feel safe. For example, it should not be left for unrestrained privatization, as the authorities would then lose control over how “closed” the facades would be perceived from the outside. How this will later be followed up on in the implementation remains to be seen.

6.3. Work Experience

The third case study carried out in May 2019 was developed by teachers at Nytorpskolan and the research team. Discussions about how the project could be organized to allow teachers to cope, given the stressful work situation they already had in the core subjetcs, led to the decision to connect the “work experience period” that all pupils have for two weeks in the 8th grade. Obviously, it was easier for the school to cope with collaboration with academics if this took place in the form of slightly freer activities and not in the respective core subjects.

The work experience period aims at exposing pupils to working life and let them try being at workplaces. This takes place in all compulsory schools but is a particularly important activity in areas such as Hammarkullen, where unemployment is high. The procedure is for the schools to find places the pupils can choose between, and then, before the pupils go out, the teachers in core subjects such as social science prepare them for the two weeks of work and follow up afterwards.

We proposed a “community builder theme” and offered the pupils a chance to work locally in Hammarkullen, and to meet us—a team of researchers and teachers—to discuss and develop knowledge about how they either already considered themselves community builders or wanted to become community builders. The idea behind working locally was to base their identity formation [45], from which they will go on to form their future working life, on what they have in their immediate vicinity.

To get there, they need to know all the strengths that Hammarkullen has, which are often invisible to them because others have the preferential right of interpretation to describe their place of residence. Hammarkullen is actually an extremely strong neighborhood. Previous research2 has shown that there is sufficient local knowledge, human resources, and power to take command when various actors with a top-down perspective try to implement measures that tend to destroy the situation for inhabitants. Children often do not know about this, however, as it all happens in the adult world.

Thirty-four pupils chose our theme, and we found workplaces with good supervisors for them who were already acting as community builders. These municipal actors included the local public housing company, the preschool, the youth center, the library, etc., and in the sphere of civil society there was, e.g., the activity center, the people’s house, and the local union of tenants.

Beforehand, in their social science and Swedish classes, the pupils were tasked with describing their expectations. Part of the preparations was to watch a movie about their area, made by older youth, and reflect on how they wanted to see their area in the future. In their notes, they expressed a wish that the area would no longer be demonized and that they themselves would not be discriminated against.

The first week of work was then initiated with a workshop day in which all of them were together, discussing their expectations and fears about the work experience period, which included implementing role-playing games where they prepared to face the adult world without being under the wings of parents or teachers. The last week ended in the same way, with a workshop where they could express what the work experience was like, how they had been treated, and how they now envisioned themselves as professionals in the future. The period ended with a rewarding percussion workshop that involved making music together, the subtext being that when you make music together, you also learn something about collective community building. Afterwards in school, they were given the assignment to reflect, in writing, about what they had experienced. It was also planned that they would start writing their CVs and add their working experience to that. Hence, in this case they also worked in an interdisciplinary fashion, involving several core subject teachers that also participated in the workshops.

The learning experience gleaned from this school-initiated case study was interesting. The pupils showed in their texts and role-plays that encountering society in this way had been a great challenge:

Before the work experience, I was very nervous and worried about what might happen... I thought they might think I was different because I come from the outlying suburbs, or because of my race. Afterwards it got better, when I saw that no one had anything against me (pupil’s note).

The experiences afterwards were both positive and negative. Most of the pupils had been met with openness and respect as well as praised for their work, while some had faced xenophobia and oppression. These pupils were hence treated like “not-yet-citizens and not-yet political subjects”—as Wicke [46] would put it—and this influenced their identity formation:

I was excited, psyched, a little unsure of myself, but still wanted to show everyone in the workplace the best I have and present a good picture of both myself and ‘foreigners’. I wanted to work not only for myself but for everyone like me, as well as against segregation and prejudices against everything and everyone. After working for 8 days it feels good. I’m proud of my efforts and maybe changed something for someone else (pupil’s note).

Those with positive experiences began to build a professional identity based on pride in their neighborhood and themselves, regardless of whether or not they wanted to work in the profession they tried. Those who were met with suspicion of course experienced it negatively, but the group’s preparations and the teachers’ continuous support seemed to make them strong enough to put the experiences into a larger context and understand what was happening. In the final role-play, we could see how they helped each other to develop strategies to meet the outside world and find their way forward in their identity formation.

One important lesson for us researchers was that such empowerment is a prerequisite for being a community builder. It is thus an important component of the tools used when children are to codesign the city and participate in urban transformation processes. Obviously, this third case study had more empowerment potential than the first did, and certainly more than the second.

Another lesson was related to the mandate given to the participating teachers. Although they had the confidence of the headmaster to cooperate in research, this was not accompanied by dedicated work time or other powerful resources to influence their institution. This meant that, after the two weeks, they returned to an ordinary structure that required all of their time, keeping them from realizing ideas about incorporating the knowledge acquired into their own and other teachers’ core subjects. For example, the plan to write CVs could (hitherto) not be realized, although it was considered an important tool for empowering pupils in the long run. In this context, it may be interesting to highlight that, in the syllabus for, e.g., social science, some learning goals were very well achieved during the two weeks:

- The links between socio-economic background, education, housing, and welfare. The concepts of equality and equal opportunity.

- How the economy of households, companies, and the public are linked. Causes of changes in the social economy and their effects on individuals and groups.

- Media representations and how they can affect people’s images of the outside world. How individuals and groups are portrayed, for example, based on gender and ethnicity.

7. Discussion—What do these Lessons Imply?

Our case studies show that it is quite possible to organize ordinary processes in which children participate in community building as part of their schoolwork, in collaboration with planners. This is in line with Cele’s and van der Burgt’s experiences [26] (27):

Indeed, when children are involved in participatory processes, this should be done through arenas that children create in their everyday life rather than through practices that are decontextualised from such everyday life (Taylor and Percy-Smith 2008).

What it would cost in time and money to do this was not investigated in the present study, as the focus of the cases was on the reactions and opinions of the actors involved. The approach of having the children participate in planning as part of their schoolwork was seen as desirable by the participants and is considered possible, even though the results show that it requires changes in the institutions involved. Determining what kind of changes should be made depends on how implementation is to be accomplished. Should it directly affect the core subjects in school, or be part of fundamentally changing the school, as a well-known policy analyst suggested more than 20 years ago:

Rather than continuing to pour money and effort into making schools and colleges more effective as institutions, Tom Bentley argues that we should focus on the connections between schools and society, relating education more closely to the challenges of adulthood. To be truly effective, education must give young people exposure to a wide range of contexts and role models for learning, along with experience of genuine responsibility. It must avoid containing them in the single, increasingly outdated context[47] (2)

With the current organization of the Municipality in Gothenburg (the ten districts still existing), the intent is that the results of inhabitants’ participation (outside voting in elections and other regulated participation) with regard to planning should reach the municipality centrally through the district organizations. During the 10-year period in which this procedure has existed, it has worked fairly well in some neighborhoods, while it has been widely criticized by inhabitants in other areas—for example in Hammarkullen [48]. Inhabitants have been dissatisfied with their views being “filtered” through local civil servants who do not fully understand and respect them, and therefore tend to convey biased opinions about them and their viewpoints.

Inhabitants are thus not satisfied with the fact that all information directed to the central municipality is filtered through the districts. What the three cases in the present article have in common is how they relate to the municipal “line organization”. All three bypass this organization in some way. Pupil’s choice uses the municipality’s own bypass system, namely the website for submitting citizen proposals. The municipality itself has chosen to place the system outside the line organization, which means that the proposals are sent from the institution handling them (Communication and Citizen Service) directly to the board they consider relevant, for example the Traffic Board. The proposals are thus not filtered through the district organizations if they do not directly relate to the districts’ responsibilities (maintenance support, elderly care, preschool, youth center). This procedure enables school children and their teachers to decide for themselves if and how they submit proposals to the central municipality. Yet it also means that the process is slow, because the line is prioritized by civil servants. Moreover, the children experienced that the proposals were juggled back and forth between institutions. This took time but was also an opportunity for them to learn, which is an important point regarding the course objectives of core subject areas. Our point here, however, is that pupils should learn not only about democracy in school, but also to advance democracy. Using systems that bypass the line organization is obviously a knowledge project per se that can help to change the municipality—but only if there are officials and politicians who engage in dialogue with the children in this knowledge process.

The second case study, child impact assessment, was designed as a pilot study run by the City Planning Office and carried out by them with a procured consultant. City district officials were invited to take part in the process and did so to some extent. As mentioned before, at present, a child impact assessment is supposed to be implemented in all planning processes. However, there was reason for a pilot study because the City Planning Office wanted to develop the tool for children’s own participation and to do so in collaboration with compulsory schools in an area. Moreover, this case study can therefore be regarded as bypassing the line organization to some extent, because it was not carried out at the initiative or as part of the responsibility of the district. Results, knowledge, and opinions were thus introduced directly and unfiltered to planners, in face-to-face meetings.

Work experience was a different case study in that it did not have the direct purpose of producing knowledge for a planning process. Rather, it examined the prerequisites for designing children’s participation based on the school’s sphere and the children’s own current situation in society. For most 14-year-olds, adulthood feels distant. However, for children living in a stigmatized area, many of whom have unemployed parents struggling with social exclusion, thoughts about the future may come very early. Therefore, starting from that issue resulted in a great deal of engagement on the part of the children in the discussions.

As shown, the three case studies had different purposes which can be related to how they were initiated. Pupil’s choice involved children 13 years of age and was initiated by researchers in close collaboration with teachers. Child impact assessment involved children 9–13 years of age and was initiated by planners in collaboration with researchers but the researchers took on a more passive observational role than in the first and third case. Work experience involved children 14 years of age and was initiated by researchers in even more close collaboration with teachers than the first case. The first two cases got results with significance for planners while the third had no relationship with them, as there was no municipal system to connect to for the type of knowledge the students produced.

The different purposes of the case studies can possibly also be related to the fact that the children were of different ages. When we analyzed the cases, we noticed a difference in how one looked at the children, i.e., their role. Both pupil’s choice and work experience aimed at transferring power to children by offering tools and support in their role of being or becoming community builders. Child impact assessment, which involved those 9–13 years of age, saw the children as informants and carried out the work to bring children’s knowledge into the planning process. They saw children as pupils, not citizens or community builders. This difference could be due to the assumption that younger children may be considered to have difficulties in becoming community builders; however, such a difference can actually be bridged by choosing appropriate tools for the age which allows transfer of power even to younger residents. We could also note that in pupil’s choice, the children relapsed into the role of pupils, when the teachers and planners failed to keep the channel between the school and the planning office open and create systems for the relationship.

Discussions in the final seminar at the end of the project brought to light an interesting and multifaceted transformation, described by the most involved teacher at Nytorpskolan (notes 2020-02-26 simultaneous documentation): in the beginning of the research project, there was great optimism among pupils concerning their potential democratic position in society. As the case of pupil’s choice developed, the optimism intensified and was at its peak when the children managed to gather 200 votes and subsequently received a respectful response from politicians. The two other cases may not have had as much democratic potential in the pupils’ eyes, but the careful outline of these processes reinforced the optimism sparked by pupil’s choice. When society then failed the pupils by not treating the citizen proposals respectfully—e.g., the bouncing back and forth, the unreasonable amount of time it took, the poor language used when answering—this had quite a large impact in that the children lost hope in democracy. Hence, it was not the rejections that influenced the pupils primarily, but the response. The teacher described how, during a period of one year, the pupils went from actively “enlightening” younger children at school by saying there was no reason for pessimism, to saying they did not intend to vote at all when they reach voting age.

The discussions about this in the final seminar went back and forth. As several of those responsible for the pupil’s choice process were present and the conversation was facilitated to work well, a great deal of knowledge was put on the table. It turned out that the municipal department responsible for the citizen proposal tool had hired a consultant to develop it and the children’s criticism of the system would play a significant role in changing the system. Thus, the intention now was to change the technology and visualization, the language in the responses, and how the process would be handled in the municipality. The pupils had contributed to this result.

The teacher received this information with interest and conveyed that it would make a great difference for the pupils when he raised this feedback in the classroom. He also stressed that this kind of learning process should have been part of the research process. There had been negative consequences of the school as a whole not participating and learning from the process and of the fact that he himself had not had the mandate to spend more time on it. He also stressed that the pupils’ declining confidence was due to the school devoting too little attention to discussing community development. It lowers the pupils’ general confidence when the school does not assume such a responsibility. However, he left the seminar full of confidence that the knowledge he gained would strengthen the pupils again, in their role as community builders.

In the final seminar, participants from the planning department began in a position where they were frightened by the fact that the children’s confidence in society fell when the three case studies were carried out. Initially they felt this was the researchers’ fault, however, this view gradually changed. The action research project had implemented the three case studies in a close collaboration between academia, the school, and the municipality. Pupil’s choice, which was most discussed at the seminar, had also submitted citizen proposals through the municipality’s own system. In this context, the teacher also highlighted a very important reason for the pupils’ lack of confidence: no planner or other municipal representative had personally returned to the pupils during school time and explained the results of the pupil’s choice process. Participants agreed that it is important to connect a communicator to the citizen proposal tool.

The seminar ended in a spirit of agreement: participants agreed that this type of research needs to be jointly designed and carried out in collaboration and that participants should be given the mandate and time to see the process to its completion. If children’s participation in planning is really about the three goals Cele and van der Burgt [26] (15) put forward—(a) children’s competencies and knowledge; (b) educational value, learning-by-doing; and (c) empowering and fostering children to become community builders—then especially for the third aim to be fulfilled, much better methods are needed than those used today. For instance, we learned from the case studies that in order to achieve empowerment, close collaboration with the school is important, because teachers know the children and know what strengthens and what hinders them. Moreover, children’s participation in community building not only needs to be adapted to the worlds of the school and planners, but also to the world in which the children live outside the school, with parents, relatives, friends, sports leaders, association members, etc. Such an outreach approach is not the most common way of working in compulsory schools today. For this reason, children’s participation in community building should not only strive to adapt to existing systems within concerned institutions, but also facilitate calling these systems into question. This is in line with previous research. Freeman stressed that planners affect children’s lives to a very great extent and that they must therefore, in accordance with UNCRC, both listen to children and let children influence planning. This cannot be conditional on planners:

UNCROC does not state that children should only be asked their views if these are given in ways that professionals can meaningfully integrate into established planning systems[49] (315)

There is also consensus in previous research that one should not be afraid of disappointing young people who are participating in research to develop society. Pupils can actually handle complex problems if they receive support from adults in different positions:

Participatory planning has inherent value in creating more sustainable cities. It also offers the potential to significantly shape young people’s view of government and their role in influencing the design of their cities. The students in this project demonstrated that they can understand complex problems, make informed suggestions, and engage in dialogue with a diversity of other people[12] (41)

Empowering and fostering children to become community builders can be done by, for example, opening bypass channels to the line organization and ensuring that we actually learn [50] from what is happening when bypass channels are used.

8. Conclusions—A Wider Context and Future Research

The three case studies have provided much-needed information on how children’s participation in planning can be carried out in such a way that it becomes an ordinary process that takes place independent of the efforts of enthusiasts. Our experience is that planning such work needs to be done in very close collaboration with teachers and pupils; it also needs to be implemented in a system-challenging manner, because a compulsory school has the opportunity neither to participate nor to benefit from participation if its systemic structure does not change. As soon as pilot projects are completed, they are typically swallowed up into the ordinary structure of core subjects, course objectives, exams, and grades. As Bentley argued (1998), the changes that compulsory schools are probably facing imply the need to actively interact with the local community and at the same time take advantage of multicultural communities’ global networks. The school systems need to change if they are to manage this development.

Naturally, the same need for change applies to planning systems. Developing participation by introducing digital tools that allow many inhabitants to systematically communicate their views and knowledge to planners is an important part of this. It allows the information to be contained in the systems used by planners, e.g., GIS-based mapping, which is a time-efficient way of gathering and visualizing knowledge. However, in order to influence the content of the planning as well, further change is needed. Planners also have to meet with children face-to-face and listen to why they think different things and learn what everyday life looks like for different groups of children, depending on who they are and where they live. Planning needs to take these differences into account. Therefore, children’s participation in planning must also challenge planners’ everyday work lives and systems, thereby contributing to its continuous change.

Therefore, rather than looking for methods and tools with potential to work in the existing school world and in the current planners’ world, it is important to design development work and research aimed at creating learning processes that can change education and planning practice. In this connection, as Hart stressed [20], children can contribute to shaping such research; they can codesign participatory processes instead of merely participating in them, and this would result in “genuine participation of children”, as Schepers et al. put it [51]. We also agree with Senbel that tool development is not unnecessary, rather it is necessary that civil society take part in developing tools and methods:

It is evident that improving dialogue to the point of empowerment requires much more than simple tool development. For visualization media to be truly empowering they have to be employed in deliberative processes that are open, transparent, and accessible, and in which decision making is shared by everyone who participates[52] (434)

That brings us back to Freeman [15] and her conflict perspective. For whom do we build the city? “For everyone”, she answers, emphasizing that virtually everything in planning impacts children directly or indirectly. Those who have been allowed limited influence earlier will, if we follow UNCRC becoming law, have much more influence over the development and be acknowledged as competent co-producers of knowledge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing, J.S. and L.F.; Supervision, L.F.; Funding acquisition, Software, Visualization, J.S. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Formas The Swedish Research Council for Environment Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning within the research project Children as co-creators of the urban space (2016-00928).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davidoff, P. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1965, 31, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, V.D.; Krumholz, N. Neighborhood Planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2000, 20, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, S.; Kothari, U. Participation. Int. Encycl. of Hum. Geogr. 2009, 8, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.; Gaventa, S. Global Citizen Action. Boulder; Lynne Rienner: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Planning with Complexity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Khakee, A.; Barbanente, A. Negotiative Land-Use and Deliberative Environmental Planning in Italy and Sweden. Int. Plan. Stud. 2003, 8, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock, L. Making the Invisible Visible; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J. Rethinking Poverty: Empowerment and Citizen’s Rights. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1996, 148, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J. Sharing the City: Community Participation in Urban Management; Earthscan: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock, L. Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cites of the 21st Century; Continuum: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Derr, V.; Kovács, I.G. How participatory processes impact children and contribute to planning: A case study of neighborhood design from Boulder, Colorado, USA. J. Urban. 2017, 10, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Shaping Urbanization for Children: A Handbook on Child-Responsive Urban Planning; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arup Cities. Alive: Designing for Urban Childhoods; Arup: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. Twenty-five years of children’s geographies: A planner’s perspective. Child. Geogr. 2020, 18, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Witten, K.; Asiasiga, L.; Lin, E.-Y. Children’s Engagement as Urban Researchers and Consultants in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Can it Increase Children’s Effective Participation in Urban Planning? Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, U.; Nordin, K. Including Children’s Perspectives in Urban Planning in GIS: Development of a Method. In Designing Social Innovation: Planning, Building, Evaluation; Martens, B., Keul, A.G., Eds.; Hogrefe & Huber: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kahila-Tani, M.; Broberg, A.; Kyttä, M.; Tyger, T. Let the Citizens Map—Public Participation GIS as a Planning Support System in the Helsinki Master Plan Process. Plan. Pr. Res. 2015, 31, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 8, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Stepping Back from The Ladder: Reflections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children. In Participation and Learning: Perspectives on Education and the Environment, Health and Sustainability; Reid, A., Jensen, B.B., Nikel, J., Simovska, V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. Florence; UNICEF International Child Development Centre: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M. Children’s Voices on Ways of Having a Voice. Children’s and Young People’s Perspectives on Methods Used in Research and Consultation. Childhood 2006, 13, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Lister, R.; Middleton, S.; Cox, L. Young People as Real Citizens: Towards an Inclusionary Understanding of Citizenship. J. Youth Stud. 2005, 8, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V. Integrating community engagement and children’s voices into design and planning education. CoDesign 2015, 11, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeten, G.; Berg, L.D.; Hansen, A.L. Introduction: Neoliberalism and post-welfare nordic states in transition. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2015, 97, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cele, S.; Van der Burgt, D. Participation, consultation, confusion: Professionals’ understandings of children’s participation in physical planning. Child. Geogr. 2015, 13, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Dellgran, P.; Höjer, S. Human Service Organizations: Conditions for the Leadership, Management and Professional Welfare Work; Natur och Kultur: Stocholn, Sweden, 2015. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Vestbro, D.U. Citizen Participation or Representative Democracy? The Case of Stockholm, Sweden. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2012, 29, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, R. Divided Cities as a Policy-based Notion in Sweden. Hous. Stud. 1999, 14, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnå, E. Playing with Fire? The Swedish Mobilization for Deliberative Democracy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2006, 13, 1. [Google Scholar]

- SOU. A Sustainable Democracy: Policy for Democracy in the Twenty-first Century; SOU: Stockholm, Sweeden, 2000. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Gothenburg City. Child Impact Assessment: Children and Young People in Focus; City of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2016. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Gothenburg City. Social Impact Assessment: Focusing on Human-Kind; City of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2016. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant, L. Urban Outcasts; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, J.M.; Buckles, D.J. Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, I.; Janssens, N. Transdisciplinary Knowledge Production: Towards Hybrid Modes of Inquiry in Architecture and Urbanism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi, N. The Placemaker’s Guide to Building Community; Eartscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Machline, E.; Pearlmutter, D.; Schwartz, M. Parisian eco-districts: Low energy and affordable housing? Build. Res. Inf. 2018, 46, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeten, G. Normalising Neoliberal Planning: The Case Of Malmö, Sweden. Contradictions of Neoliberal Planning; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Allelin, M. School of Profitability: About Students’ Market-Adapted Conditions and Everyday Life; Arkiv förlag: Lund, Sweden, 2019. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Kahila-Tani, M.; Kyttä, M.; Geertman, S. Does mapping improve public participation? Exploring the pros and cons of using public participation GIS in urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 186, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severcan, Y.C. The effects of children’s participation in planning and desig activities on their place attachment. J. Archit. and Plan. Res. 2015, 32, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, K.; Kearns, R.; Carroll, P.; Asiasiga, L. Children’s everyday encounters and affective relations with place: Experiences of hyperdiversity in Auckland neighbourhoods. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 20, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, K. Textbooks, Democracy and Citizenship. Constructions in Social Science Textbooks for Upper Secondary Schools; Gothenburg University: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, T. Learning Beyond the Classroom: Education for a Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S. The role of trust in shaping urban planning in local communities: The case of Hammarkullen, Sweden. Bulletin of Geography. Socio Econ. Ser. 2018, 40, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.; Ergler, C.; Guiney, T. Planning with Preschoolers: City Mapping as a Planning Tool. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beairsto, B.; Ruohotie, P. Empowering Professionals as Lifelong Learners. In Professional Learning and Leadership; Beairsto, B., Klein, M., Ruohotie, P., Eds.; University of Tampere: Tampere, Finland, 2003; pp. 115–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schepers, S.; Dreessen, K.; Zaman, B. Rethinking children’s roles in Participatory Design: The child as a process designer. Int. J. Child Comput. Interact. 2018, 16, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbel, M.; Church, S.P. Design Empowerment: The Limits of Accessible Visualization Media in Neighborhood Densification. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In Sweden, school is compulsory for ten years, from 6 to 15 years of age. |

| 2 | See, e.g., urbanempower.se and mellanplats.se |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).