Abstract

This exploratory review of the literature provides a comprehensive overview of the settings that are available to the planner when managing participatory strategic planning of spatial socio-economic development on the local level. We contextualize individual potential configurations of participation in local development planning practice, documented in a number of case studies from different parts of the world, in order to reflect the multidimensionality of the participatory planning process. These reflections are used to build a participation plan model, which aimed to help local planners, especially local governments, to optimize the participation of local stakeholders, according to the specifics of the local environment. The paper evaluates the options of planners to manage the participation from perspective of the organization of participation, the determination of its scope, selection of stakeholders, methods and techniques of communication, decision-making and visualization, as well as the deployment of resources, or the possibility of promotion and dissemination of information. As a practical implication of this review, we compose a participation matrix, which is intended to be an auxiliary tool for planners to establish own locally-specific participation plans and that can serve as tool for education, or life-long learning of planners.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of public and various stakeholder participation in spatial development planning has a long history, and there is a huge volume of literature related to it [,,,]. The term itself has a wide range of definitions [,], while the majority of scholars define it as the collaborative involvement of participants in the decision-making processes [,], being connected with preparation of development strategies and action plans []. Participation should optimize the setting of development goals and increase the value of development programs by better optimizing them towards the real needs of spatial actors [,,].

Despite an initial increase in the direct financial costs and opportunity costs of planning, participation is intended to generate value that pays off for these costs through meaningful territorial development in the implementation phase, when it actually generates time []. On the other hand, many authors have tried to dissolve many dilemmas of theory and practice of participation [], such as conflicts of interest, conflicts between collective and individual interest, discriminatory stakeholder selection, tokenism, a lack of time and experience of local stakeholders, overcoming the knowledge filter, and many others [,,,,].

Since Arnstein [] came up with a one-dimensional analogy of the ladder, the practice of participation has changed considerably, and many scholars document that it has progressed to the highest steps []. Participation is mainly deepening through the involvement of local communities and neighborhoods []. With the institutionalization of local communities, the concept of co-creation [] and co-design appears [,,], which refer to a highly collaborative form of planning with the wider involvement of local communities that directly specify a development plan in an open innovation process [] and, followingly, participate in its implementation [,,].

Although participatory planning at the local level is already a relatively common practice in the US and Western Europe [], information on various aspects of setting up a participatory process in empirical and review studies is fragmented due to the wide range of issues and phenomena that may be associated with participation [,,,]. It is the result of the multi-dimensionality of the participatory process, which is influenced by a wide range of factors, such as the policies of local government, continuity of the process, local customs, prevailing values, sectoral structure of the local economy, hierarchy of relations in local society, involvement of local communities, etc. [,,,].

The review took a very different direction from other reviews of the participation on creation of strategic documents—the perspective of planning and securing participation in efficient way while using a participation plan as a planning tool. Our objective in this exploratory literature review will be to merge a “puzzling knowledge” about the possibilities of sett-up the management of participation. The review will be helpful tool for practitioners in terms of setting-up a local framework for participation management and also as a tool for life-long learning of planners. In this way, the literature review will not only deliver valuable implications for practitioners designing the participation on strategic planning, but also the extension of the theoretical framework of the participation possibilities, as reflected in the historical context of participation development. A participation matrix was compiled as a result of identified configurations of participative process in different fields, while this matrix can serve as a handy tool for planners in early stages of participation plan designing.

2. Materials and Methods

This review study is based on the methodology of a narrative literature review [] rather than a systematic one. We adopted this approach due to the considerable fragmentation of the topic, the huge amount of available literature, and the need to change the requirements for searched content. This exploratory literature review is intended to present a comprehensive, critical, and objective analysis of current knowledge [] on the topic of public participation on the creation of formal, local strategic development plans.

From the methodological point of view, the methods of content analysis [] and text mining [] were used for the processing of the information in studied material. The resulting synthesis of knowledge, especially from case studies, is intended to provide a framework for defining a participation plan, by which we understand a set of procedures and methods for achieving objectives related to securing the involvement and participation of citizens and other spatial actors in strategic planning [].

We have worked with formal local development planning studies and studies examining participatory strategic planning on the lower, community level, given the growing demands on local governments to adapt models of community-led, open-source planning, or co-designing of local development plans []. The results of the review answer the following research questions:

Q1:

What settings does the entity responsible for designing the participation plan have, and how can a participatory plan be drawn up based on these options?

Q2:

What models of organizing the participatory process were noted in the examined studies, what was the breadth and depth of organized participation, what types of costs associated with participation were recorded?

Q3:

What methods and tools can be used to facilitate participation in planning, in particular in ensuring communication, data collection and modelling potential development pathways?

There are still some important remarks to be discussed. First of all, it is necessary to clarify why we are also working with a review of participatory methods and procedures, which may seem to be “obsolete” in the conditions of Western Europe and the USA. This literature review is the result of the demand for a comprehensive summary of the possibilities of designing public participation in the planning of actors of community initiatives and local governments in the conditions of the Visegrad countries. The article will serve as a basis for designing participatory plans in the conditions of Slovakia, while it should serve as a kind of “guideline”. In the conditions of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the traditional planning models can be still observed with limited participation, being still largely tokenistic in its nature [].

This overview brings together “puzzling knowledge” regarding the different possibilities of involving local actors in local development decisions. We will not describe, in depth, the researched case studies in the literature, but rather comprehensively summarize their knowledge in relation to the establishment of participatory processes in planning. Within the life cycle of the strategic plan, we will focus on the participatory processes in the pre-implementation phase, i.e., in the phases of plan preparation until its approval.

We used the Scopus database to obtain information about the available literature, in which we searched in the first step for articles focused on modelling and co-designing the participatory process of strategic spatial planning while using the keywords “participation”, or “participatory” and “strategic planning” simultaneously, whereas these terms were filtered within the title of the article, abstract, or keywords. We limited the search to scientific articles. A total of 294 search results were obtained, which were then individually studied and sorted in the second round of selection, as we wanted to perform a deeper filter of publications “manually”.

The exclusion of articles that do not meet the following criteria was the subject of the second round of classification: they focus on partnerships or projects that were very closely specialized in a specific socio-economic area of development, did not have a territorial link, and did not contain results that bring knowledge regarding models and procedures of participatory strategic planning processes. After this round of classification, we reduced the range of in-depth case studies and empirical studies to 31.

Appendix A summarizes the final initial selection of case studies and empirical studies for our literature review. However, after processing these studies, we still identified large gaps in knowledge that needed to be filled by the secondary pooling of resources. In this additional selection of sources, we used the ResearchGate service, which provided us with articles from various databases. To filter publications, we used a number of keyword combinations with respect to a given knowledge gap, which we needed to fill, in order to achieve the coherence of our decision-making framework for the organization of participation. In this final round of source identification, we included another 61 sources for the review.

3. Results

Citizen participation is transforming considerably in the 21st century, as in the case of other socio-economic movements. These transformation processes have led to the emergence of a new paradigm of participation []. The classic bilateral model of civic participation, which assumes that citizens respond to a formal plan that is prepared by the government or self-government in a formal setting, is replaced by an open, multi-dimensional model. In this model, the participation is facilitated through informal communication channels from the beginning of the planning process []. Such a setting should lead to the standard that citizens participate in planning on many forums of local or regional society in parallel, with one citizen often representing the attitudes of several sectors, communities, or activities, given a higher level of involvement [].

Discussions on participation in local development planning have, in recent decades, sought to answer questions as to how the process should be deliberated [], to what extent and at what stages it should use the tools of direct democracy [], or what are the costs and benefits of participation, i.e., when and to what extent participation is effective []. In recent years, the term co-design of strategic plans emerges. This term no longer reflects the “involvement” of local actors, but rather the “co-creation” of the strategic plan by various actors []. The application of innovative practices that will make it possible to “compile” a local development plan from the needs of smaller local communities is becoming a priority for local development in the 21st century. The next chapter discusses the question of the extent to which local governments, as coordinators of local planning, can take over participatory planning patterns from community initiatives and local development partnerships.

3.1. Is the Participative Co-Creation of Plans an “Ivory Tower”?

Several authors suggest the opening local development planning to the public, de-liberalizing the strategic plan preparation process, targeting more local grassroots communities and neighborhoods, or their architects [,,,]. However, many local governments in the conditions of the Visegrad countries are experiencing decision-making paralysis in effort to find the way, how to transform the creation of a strategic plan into participative process, as the legislative framework requires, and, thus, include tokenistic participation, by which is a central European space characteristic [,]. A number of case studies map the benefits and positive impacts of participation on the development and sustainability of localities and local communities, e.g., [,,,,,]. On the other hand, even in the conditions of Western Europe and the USA, many authors perceive significantly open participation and community-led plans, such as Ivory Tower (a metaphorical place where a given phenomenon acquires perfect, idealistic features and meanings), due to many barriers that local governments perceive as a development coordinator in applying participative planning models []. We will use reverse logic to critically review the potential for co-designing local development plans, starting with the arguments for “Ivory Tower.”

Table 1 summarizes some of the key barriers to open strategic planning. Probably, the main difference between the planning of local grassroots, as well as formal local strategic plans managed by the local government, is the degree of formality and binding nature of plans, as community and partnership plans do not necessarily commit their members to specific action, as compared to the regulatory nature of local development plans []. Legislative barriers on the side of local governments of course exist, e.g., in the conditions of the Visegrad countries, the legislation does not allow them to delegate decision-making power [], but, at the same time, local governments do not seek innovative forms of strategic planning that would allow for co-creation in accordance to law [].

Table 1.

An overview of barriers to the development of public participation in formal strategic planning.

Other barriers, being perceived, in particular, by local governments, include a higher degree of politicization of strategic planning and clientelism in stakeholder involvement [], the lack of local community planning experience [], lack of time on side of locals for long-term engagement in planning [], or lack of skills for operating ICT systems, low access to online surveys, or lack of skills for work with geo-planning systems []. Some types of actors, such as environmental activists, non-profit organizations, or neighborhood representatives and marginalized groups, have, in the past, found it more difficult to participate in participatory planning [], as their importance to the process was not recognized.

At the peak of criticism is the question of the effectiveness of open approaches and broad participation. There are clearly situations where participation can be counterproductive []. At the same time, some authors refute the common notion that public participation in planning does not lead to increased costs []. While planning costs at the grassroots community level can be minimal, organizing physical meetings, securing free spaces, rewards, or other overheads and technical support costs, especially in the case of larger cities, can result in significant financial and non-financial costs []. At the same time, excessive participation can lead to the overproduction of ideas and subsequent escalation of conflicts [].

In addition, local development planning does not have to be deliberated if the strategic plan does not follow the broad-based development of local communities, but only the setting of investments in public services, the procurement of equipment, and the like []. Thus, when deciding on the form and degree of participation, each local government should be based on real needs, the state of development of the involvement of local stakeholders, and the requirements of the form of the strategic document.

3.2. From Participation to Co-Creation and Co-Design

Despite the outlined criticisms, there is a considerable body of literature that emphasizes the importance of civic participation in strategic development planning. The 21st century, a local development strategic plan should be based on the needs of local social movements and communities [] and, so, these barriers can be overcome through a community-based approach and innovation in the way that participation is organized [].

How does participation differ from co-design? Co-production and co-design are very broad terms that, in the connotation of participatory planning, express the processes of collective creativity [], used by various agents in a territory that cooperatively design a strategic document, program, or processes []. When co-designing a strategic plan, local communities are invited not only to provide their views and expectations, comments, and suggestions, as in the case of participatory planning [], but to use their own creativity, knowledge and skills for active, engaged co-creation of a strategic plan []. Co-production processes are increasingly characterized by the use of online platform tools, open-source databases, geo-planning systems [,] to integrate different forms of data collection and advanced communication tools, to deepen mutual understanding, share inspiration, and increase engagement among participants in the strategy design process [].

Several case studies already point to planning practice in local development, which is based on the principles of co-design. The most significant source of knowledge is probably the experience of the United Kingdom, which has been applying the “community planning” that has arisen from national legislation since 2011 []. This policy of localism has made it possible to move the creation of development plans along the vertical axis down to the level of smaller local communities that, however, need to be formally institutionalized—those can be municipal or parish councils, but also the so-called community forums []. The neighborhood plans themselves are based on building a gradual consensus. After the draft document is created, it must be approved by an independent evaluation, and then go through a local referendum. Neighborhood plans must be in line with higher strategic documents, whether at the local or national level. Therefore, compliance with higher documents is organized on top-bottom axis.

Case studies of municipalities that describe the co-design of public plans, using the alternative communication and open-source data platforms, are very unique and they have the character of experimental practice. A significant example is the “Quartiere bene comune” project in Reggio Emilia, which started in 2015, during the period of appropriate legislative conditions (abolition of districts and requirements for broad horizontal participation in planning). Within this experimental project, the city formally defined the institutionalized neighborhoods (communities), as represented by community architects. In the first phase of the planning process, the neighborhoods, in cooperation with the municipality, identified key projects and programs for community development. Subsequently, the communities formed “open laboratories” for open discussion between the community and external actors, while using open space technologies, which first helped to prepare and later comment on the draft of “civil agreement”. The local government subsequently approved this draft community strategy [].

Even within the framework of legislation that requires the distribution of resources for development projects by the local government, and in conditions when any sub-local plan must be approved by local authority, it is still possible to support a community planning. However, we will take our literature review in a different direction in the following chapters. Our goal will be to summarize the “settings” that can be used by local governments in different institutional conditions, in designing participation in the planning process of various degrees of formality. We will summarize these configurations in the form of a potential set-up of the participation plan, which should define options for creating a locally specific road map to reach the participation in local development planning.

3.3. Setting-Up the Participation Plan

Some studies suggest the compilation of a so-called participation plan to set out a strategy for achieving the required participation of citizens and other socio-economic actors []. However, a number of empirical and case studies that mapped specific set-ups of participatory local development planning confirm that participatory processes were not based on any guidelines. Thus, investigated municipalities, or local community initiatives, had to improvise, when organizing the participation [,,,]. Our original intention was, through a narrative theoretical overview, to summarize from existing studies the possibilities that the coordinator has to ensure participation in the strategic plan. However, during a study of the literature, we concluded that these participatory strategic planning practices and tools can be summarized in a structured plan for organizing participation that received almost no attention in the scientific literature, even though there are references to them [].

The stage model of participatory design of the strategic plan that is presented in the following chapter is only a summary of the possibilities that the coordinator of territorial development strategic plan possesses, when trying to create a coherent participation plan [].

At the same time, before we move to the following subchapters, it is necessary to clarify the terms of “local planning”, “urban planning”, or “local plans”, which will be used in our review to indicate the same thing—spatial development planning on the local spatial level, or management of local economic and social development plan preparation. The term “participation” is very generic in relation to local planning, but we would define it similarly to Martínez [], as a set of procedures according to which “civil society” or local development agents who do not “rule”, nor do they have direct decision-making power in local development, they use their abilities to intervene in the planning of collective life.

Additionally, the ethical challenges that are connected with management of participation in local development planning should be mentioned. It is necessary to pay attention to how coordinating bodies, partnerships, working groups, or community representation bodies are established, how the power and competences are delegated to engaged groups and individuals and how control mechanisms will be set and monitoring exerted []. From perspective of ethics, it is important to adapt participation policies and organizational models to ensure public and participant awareness and access to information, no relevant actor could be excluded from the planning process in a discriminatory manner in order to maintain an inclusive approach to the organization of planning processes [], stakeholder selection on the basis of pre-established rules should be secured, the principle of anonymity and confidentiality in the processing of data that are obtained from local stakeholders should be adhered [], planners should meet the time frames set for given processes and activities to avoid mismatch between schedules and expectations [], and others.

We have divided the configurations of the participation plan into the areas: setting-up the goals of participation, organization of participation, selecting stakeholders, determining the depth of participation, methods and techniques of participation, defining resources for participation, and ensuring the promotion and dissemination of planning information.

3.3.1. Setting Up the Goals of Participation

Involving local stakeholders in the preparation of strategic plans can only create value if participation pursues realistic goals []. By setting participation goals, local planners seek answers to the question of what participation should actually serve in the strategic planning process and what the results should deliver. To answer these questions, we can bounce back from the one-dimensional parallel of the “ladder” [] or the multi-level models of Maier []. The higher local governments “climb” the ladder of participation, and the more significant shifts in participation goals from information to empowerment are observed.

The aim of participation in traditional administrative-led strategic planning is mainly to inform the population [], in the participatory strategic plan to obtain preferences and collect “potential projects” that meet the needs of local actors [] and in the co-design to empower communities to take responsibility for their own development []. However, each strategic planning process is unique [] and it can be defined by a very different mix of many other goals that participation can pursue. These three basic kinds of strategic planning from perspective of participation can be significantly differentiated in different localities. Within traditional planning, local governments can “inform” the population in different stages of plan preparation, and participatory strategic planning can be significantly differentiated in terms of goals, openness of processes, the breadth of local actors involved along the horizontal axis, the tools and platforms used, and other processes [].

In addition to the basic goals of individual types of planning-to inform, include, and empower [], participation in local development planning can be mainly used for the purpose of: (1) educating local actors and the population-e.g., on local regulations, the development of individual socio-economic areas of local life, but also for acquiring technical skills, such as the use of ICT tools [], (2) increasing the level of compliance of local actors with the direction of local development [], (3) strengthening the community, building community awareness, and deepening mutual trust between actors [], (4) changes in the value structure of the population and the building of local multi-spectral engagement [], (5) identification of problems of individual target groups [], (6) collection of project intentions [], and (7) initiating the institutionalization of communities and neighborhoods [].

The participation goals must pursue a concrete benefit and be cost-effective as well as achievable []. The specific goal of participation may lie down in tokenism—that is, the goal of formally ensuring participation because it is required by legislation, or to convince the local population that the plan reflects the real needs of the communities, without delivering any value added []. Thus, participation is not a goal, but a journey. In many localities, it was not only a tool for optimizing development trajectories, but also a tool for building and strengthening communities, as regular communication, meetings, mutual exchange of information on needs, and attitudes significantly helped to build consensus around solutions for local challenges. The institutionalization of local neighborhoods was, in several cases, rather a result than precondition for co-designing of strategic plans.

3.3.2. Organizing the Participation

One of the key issues in the local development planning is how to organize participation. At this point, two main questions arise from the literature, namely: (1) how should strategic planning itself be designed in terms of participation requirements? (2) Who should coordinate participatory processes?

When evaluating possible alternatives to participation in local development planning (Table 2), we select from the literature and only generalize those models that are no longer based on the principles of authoritarian or totalitarian society. Maier [] described planning, in which the local government resigned on the regulatory function of planning and invested in virtually any advantageous and feasible projects without collecting data or providing information to the public, as the so-called “supplier” planning.

Table 2.

An overview of the types of participatory approach and coordination options.

From other approaches, we identified the so-called a “traditional administrative approach”, which is characterized by the application of a conventional model of strategic plan making and public involvement on the level of informing regarding the results of the planning process after plan approval [], or, at most, tokenistic involvement of the public and local actors []. However, over the last two decades, local governments “from Western Europe to the East” have had to gradually implement participatory strategic planning procedures due to the legislative requirements for opening the planning process and identified needs to include local experts. However, this concept is not necessarily defined by the requirement for “broad participation” []. A distinctive aspect of “participatory planning” is the involvement of the public, private, and civic sector actors in planning through public meetings, participation in working groups, organization of focus groups, and the like [].

The another “level” of this approach is the “co-design” of goals and projects within the action plans of strategies, utilizing various tools to support creativity, or finding a common path []. Within this model, the local government collects opinions, attitudes, and project proposals from local actors that should actively contribute to formulation of drafts on community level []. As part of the concept of co-designing the local development plan, citizens are asked to set aside the “NIMBY” approach (not in my court) and actively cooperate within the neighborhood and with the local government. In this case, the territory becomes a meeting place and a tool for restoring the relationship between the citizen, the neighborhood, and the local government. Conflicts of interest occur in neighborhoods where consensus is being built []. Regardless of whether the process is participatory or co-deign at the community level, the degree of participation has been significantly differentiated in the case studies. However, despite the growing role of communities in strategic planning, local self-government remains the entity that is responsible for formal local development planning, not only in the conditions of Central European countries, but also in Western European countries.

The creation of a participation plan should start by appointing an entity that is responsible for facilitating the preparation of a participation plan or participation program. The choice of facilitator is usually the decision of the local development authority-local government, or municipal council, if the establishment of specific coordinating, or supporting board require legitimization by elected decision-making local authority []. Participation can be coordinated by a local actor with political power [], a local actor with political power in cooperation with a support or advisory body (advisory boards and committees for the preparation of a strategic plan), or fully mediated. Indirectly, the mentioned coordination or support board can also fully manage the process [], with different scope of competencies. However, the partial delegation of participation management to representatives of institutionalized communities, neighborhoods, and civic forums may be a specific case [].

The supporting or coordinating bodies for the management of the strategic planning process can be composed not only of local government representatives, but also of the initial list of key local actors, chosen mainly on the basis of existing relationships, their importance for local development, or other determinants []. However, any organizational model of participation must be based on national legislation and, thus, often requires the approval of community and neighborhood proposals by the local government representative body [].

Although the central government policies in most of the examined cases imposed an obligation to involve local actors in the planning process via law, central institutions did not provide guidance for the management of participatory strategic planning. Therefore, cases of community-led planning are rather an experiment in localities with highly institutionalized communities and neighborhoods, which have strong leaders and are ready to take on the tasks of sub-local planning as well as build internal models of decision-making. In such still largely idealized cases, it could already be said that only a minority remains silent in relation to the creation of a local development plan.

When preparing a participation plan, it is also necessary to address the issue of the size of these bodies, or the size of working, and other, specific advisory groups [].

Subsequently, planners should address the “breadth” and “depth” of participation and, thus, answer questions regarding what types of actors to involve and to what extent.

3.3.3. Determination of the Target Group

At this stage of the participatory plan configuration, its coordinator should compile a list of actors and summarize their interests and potential benefits in the planning process []. The coordinator must appropriately estimate the potential contribution of the different groups of actors and include it in the strategy for their involvement. From the authors’ experience, it should be included as a suitable and common methodological tool for identifying key actors implies a stakeholder analysis or a network analysis []. The nomination of groups of actors, or specific actors for strategic planning, is usually the role of the coordinator, coordination committee, or other initial working groups for the preparation of the local development plan [].

The types of target groups that are involved tend to be highly differentiated in local plans []. However, the most commonly studies mention local government actors [], local entrepreneurs and business associations [], non-governmental organizations and informal groups of active citizens [], local experts [], neighbourhood representatives [], specific local partnerships [], universities and private research institutions [], environmental activists and their organizations [], marginalized groups [], and representatives of urban areas [], and, in the case of institutionalized neighbourhoods, community architects [], or highly-specific grassroots communities in the locality and their representatives [].

This decision should, in addition to knowing the needs of planning at each stage of the preparation of the strategic plan, also be based on knowledge of the specific composition of local actors, local economic, and socio-cultural conditions []. In some studies, an alternative requirement for equal representation of participants according to the nationality key [], or the age structure of the population [], appeared. Maier [] recommends dividing potentially engageable actors into those who have to be directly involved (actors with power, experience, education, or access to information) and those whose roles in the process are to be limited to comments, or ex post evaluation.

The opposite of creating the initial list of involved actors is an open-source set-up of processes—i.e., open calls for participation without regulation of participants []. However, this approach cannot be applied to all types of participatory activities []—the local government can convene meetings only within the available organizational capacity, resources, available physical spaces, etc.

It is the development of modern technologies that created ground for successful application of open, especially “online” planning procedures. Virtual meetings, data collection in the form of online surveys, or local ICT planning platforms that are characteristic of co-design of plans, make it possible to improve the possibilities of opening participation []. However, at this point, we come to the potential problem of “over-participation”, or to negative experiences with “excessive” public involvement, which is mainly the subject of deciding on the extent-depth of participation.

Participation should be selective. Open participation for random stakeholders or citizens in most cases resulted in the inability of planners to facilitate communication or effectively collect valuable project intentions. Sub-local plans and proposals from communities and neighborhoods were subsequently incorporated into local development plans that are based on the cooperation and negotiation between local government representatives and neighboring architects in order to maintain the sustainability and efficiency of the planning process.

3.3.4. Determination of the Extent of Involvement

Already during the earlier periods of the second half of the 20th century, see, e.g., [,], the authors emphasized the need for mass information or involvement of local actors in local development planning, as it is significantly more effective than bilateral meetings or interviewing individuals []. However, to what extent should be local stakeholders involved into participation? For example, with the growing scope of civic engagement in local development planning, the authors demonstrated an increased ability of participants to process information, create new ideas or solutions, and reach consensus, which actually re-shape their attitudes towards local problems [].

Only a limited proportion of citizens sometimes participate in full participatory planning, which include various forms of meetings over a number of years. One-time participation is a much more common example of participation, where the participant participates in one-off workshops or focus groups []. For this reason, it is necessary to decide in which phases of the planning process the individual groups of participants should be involved, and how intensively []. Civic communities can greatly help to create smaller projects and changes in local development, but their involvement in the management of development priorities and large investment projects is already considerably more limited, given their experiences and knowledge capacity [].

Large groups of participants should be involved, especially in the creation of visions, setting higher goals of strategic plans, it means to planning large movements within a given community, while smaller groups may be involved due to their specialization, education, and experience in thematically narrower working and focus groups []. At this point, the participation plan should, in particular, define the needs for the involvement of different volumes of participants in the various stages of planning and then specify the preconditions for their participation (in the case of citizens e.g., residence, employment, education, and other prerequisites, in the case of businesses e.g., seat, sectoral affiliation, adoption of corporate social responsibility practices, and others).

The participation plan must also define how will the communication and collection of information be processed using participation methods in order to avoid the situations described by Ghose [], where participation leads in the opposite way to increased tension in communities due to the involvement without real integration of stakeholder’s attitudes into the final plan. With the increasing level of participation, the pressure on coordinators to manage conflict of interest management grows []. The consideration of involvement extent is crucial, especially in urban planning of larger settlements, as overestimating the need for participation can lead to a low level of consideration of community requirements in the final plan []. The high level of participation brought about thousands of proposals from the population in selected studied localities and, after the approval of the draft plan, tens of thousands of comments, ultimately led to a reduction in the efficiency of the process []. With increasing participation, there is necessarily not only an increase in social consensus, but also, on the contrary, an increase in tension between selected interest groups [], so the municipality must choose appropriate facilitators for each type of meeting who know the environment, stakeholders, and their attitudes and conflict management.

Additionally, the timing of participation should be part of the planner’s work on the participatory plan []. Participation can be ensured from the very early stages of planning, when the basic directions of the plan are conceived, to the final stages of pre-implementation phase, associated with open meetings to the final draft []. At the same time, Wondolleck and Yaffee [] believe that participation is key in the pre-planning phases of planning, when it is most effective in including the attitudes of socio-economic actors to deliver the intervention logic, allowing plans to be tied to the target groups problems and needs Some case studies, e.g., [], show that even well-established participatory planning processes can fail in lengthy preparations and administrative processes, or inappropriate setting of time for data collection and organization of meetings. Some studies, such as Kinzer [], confirm that, with the increasing time costs of planning, the enthusiasm of stakeholders for implementation decreases.

The level of involvement is also a question of the structure of competencies that the participating stakeholders have to acquire for the planning process. It is possible, e.g., to call on experts who can help to analyze the problem from a professional point of view and propose solutions to be adopted, but, on the other hand, there are stakeholders and citizens who may not have competences that are similar to those of experts and will bear the consequences of the decision []. From the point of view of preparing a participatory plan, local actors have a certain “strength” or “decision-making power” on two levels—the first level results from their competencies in the planning process and the second level is their objective strength, professional capacity, position in local structures, or influence []. Knowing the strength of the actor’s influence in the locality and their appropriate involvement is important for planning facilitators, especially due to the need to build consensus []. The authors recognize different types of competences of participants. Their role can only be limited to “listen”, i.e., to be informed, “provide” information relevant to the creation of the plan, “consult”, which already expresses the competence of the stakeholder to comment on proposals, “participate” in the long term to be a partner in planning to formulate intentions, projects, and participate in the physical preparation of the plan, or even “approve” drafts or community requirements [,].

3.3.5. Participation Methods and Techniques

Participatory strategic planning and strategic plan co-design pursues the achievement of benefits from participation, whether on the field of obtaining the spatial data, new ideas, project intentions, or civic proposals []. The summarized methods of communication, data collection, and visualization of planning pathways make it possible to achieve these benefits, make the participatory process more efficient [], and generate secondary effects in the form of networking, deepening understanding, learning, and others [].

Table 3 summarizes the possibilities of planners in organizing a forum for joint communication or work in planning. From traditional administrative planning to the co-design of strategic plans, we recognize a large number of communication tools that are used in case studies. The communication tools summarized in this way provide an overview of the development of participation over time, from purely non-participatory or low-participation tools, as decisions or public hearings [], to communication and information sharing on locally, specifically designed online communication platforms [,]. The use of online tools greatly helps to keep planning processes open by integrating a wider range of actors [].

Table 3.

An overview of communication tools used in participative planning.

When designing online communication, we must not forget to mention the decision on the degree of formality of discussions, meetings, and working groups. Although local government-coordinated meetings with local actors are usually formal, many authors emphasize the growing role of semi-formal or informal atmosphere and communication in planning [,,]. In addition to communication tools, in this subchapter we would like to summarize the identified simulation methods and DSS (decision-support systems), planning visualization methods, and data collection methods for planning, which can help planners to create an idea of how to use participation and transform it into meaningful results [].

To begin with, to avoid confusion, it should be noted that the following recommended methods differ in terms of their complexity and scope of use in the planning process. Some of the authors in the literature also cite methods, which, in terms of their complexity, can be understood as methods of organizing the very process of creating a strategic plan.

Popular examples include, e.g., backcasting [], a process that begins with the participatory definition of the optimal future and continues by moving back to baseline state of development, with participants gradually defining activities that connect the future and present [].

Popular examples include, e.g., backcasting [], a process that begins with the participatory definition of the optimal future and continues by moving back to baseline state of development, with participants gradually defining activities that connect the future and present [].

Other models try to predict future sequences of events. For example, scenario analysis [] is used to predict the future sequence of events, by creating alternative scenarios, based on which critical points in the decision-making process are to be identified. Some approaches analyze strategic planning in terms of how it can be improved by adapting agile project management, such as APA-agile project management []. APM, which can also be considered a practice of co-creating plans and projects, consists of a set of methods and principles that were originally conceived for flexible and participatory software development, applied to the planning process []. At the moment, we are only registering a few models of decision-making on how local actors participate in strategic planning, such as the Vroom-Yetton model applied in ecosystem management [].

Regarding less complex, specific visualization, and DSS methods, it is possible to distinguish between technologically undemanding and more demanding methods and techniques. Participatory mapping can help to visualize different perspectives of processes and relationships and provide critical points for discussion of different potential projects and development directions. It is a modern technique of cartography that is based on common drawings of the local environment, while recording relationships and activities in space is so simple that all members of the group can process the information []. Several authors mention the utilization of design thinking that includes the processes of contextual analysis, identification and formulation of problems, creation of ideas and solutions, and the stimulation of creative thinking, visualized by various methods (e.g., collaborative composition of a map of problems through colored labels, etc.). The participants examine the problem and its context, and it may reinterpret or restructure the problem to achieve a specific framework []. The use of logical matrices is also a relatively common method that is used mainly for project design, monitoring, and evaluation []. For the purpose of comparing paths and attitudes, specific tools of psychology can also be used, such as repertoire grid analysis (RGA), which makes it possible to identify the ways in which a person constructs (interprets or makes sense) his experience [].

Among the more technologically intensive, we will mention especially geographic information systems, which are used in the conditions of many local governments to increase the degree of participation and effectiveness of decision-making on the use of space, or the visualization of activities and projects in space []. However, their use encounters two basic problems—the knowledge filter problem, which excludes certain participants from using this method, and, at the same time, the method still does not allow for complete process openness, as the selection criteria and elements for GIS are still set by coordinator [].

It is possible to stimulate goal setting or resource allocation when co-designing a strategic plan through the tools of behavioral sciences, specifically using the behavioral games. Behavioral games allow to model the achievement of consensus regarding the optimization of selected goals, activities, or to optimize the distribution of resources. However, this method requires its correct design, especially with regard to 3 main principles []: (1) it must allow “players” to form their own beliefs on the basis of an analysis of how others can decide, (2) to provide space for the best possible options for action or decision-making; and, (3) to create space for the optimization of these decisions, so that consensus can be reached.

In addition to methods that are presented above, it is possible to use software-based methods, which use classical methods of socio-metric research, such as opinion gauges []. Interactive collection of data and attitudes of the population can also be addressed through specific online ICT platforms [], which integrate the use of open-source tools and integrated technological infrastructure, enabling a high level of interaction between actors in planning. These platforms usually integrate traditional methods of data collection and displaying and innovative interaction tools []. The scope for the use of such systems in local planning is considerable, especially given the diversity of the systems they can combine—e.g., CMS (content management systems), geo-portals for collecting information from the territory, online surveys, social mapping tools, or citizen alerts [,,]. However, an implementation of modern communication technologies and tools raise the question of possible broadening of digital divide, as not every citizen can have access to internet, or the required skills for managing work in software required for planning.

The tools that have been described can be critical to the successful facilitation of participation. For example, decision-making supportive systems can significantly accelerate the process of building consensus in setting goals, selecting projects, or specific places to implement strategic plan activities. Communication tools can, if properly set up, be a prerequisite for a significant reduction in the transaction costs that result from participation. Therefore, planners should have an overview of the communication, decision-making, and visualization tools that are used to facilitate participation or to deliver locally-specific innovative practices in this regard.

3.3.6. Costs of Participation

Participation planning is also linked to cost planning. The main source of information on the costs of participation were case studies, the authors of which performed cost-benefit analyses to determine the effectiveness of participation, see, e.g., [,,,], and an extensive review of the costs and value generated by [].

Table 4 summarizes the types of costs that municipalities have associated with public participation in planning. Depending on its extent, participation generates direct financial and non-financial costs [,]. Most of these costs are borne by the local government as a planner [], but Angraeni et al. [] also draw attention to the cumulative cost of individual participants, which must bear, at minimum, the travel costs. The activity performed within the framework of participatory planning on a voluntary basis (free of charge) also represents the opportunity costs []. The coordinator of the planning process must take a wide range of direct, financial costs into account, from personnel costs of own management, through the costs of ensuring participation management through the creation of coordination and advisory bodies, costs of creating special ICT tools, software purchase, costs of external facilitators, representation costs, travel expenses, technical costs associated with the provision of premises and technical equipment, costs of communication and the dissemination of information, and much more [,,,].

Table 4.

Direct and indirect costs of local governments from participation.

A number of authors [,,,,] emphasize significant indirect costs, especially in terms of opportunity costs that are associated with a significant extension of planning time process. Other frequently cited indirect and non-financial costs include the potential escalation of conflicts of interest between interest groups, changes in relations between local government and some stakeholders, and the potential loss of local government support or the loss of autonomy and representation. Therefore, participation should not be thought of as a process that generates value without investment []. In addition to the costs on the part of local governments, individual participants must bear some direct or opportunity costs [], and their costs may also determine the achievable extent of participation []. The performed cost-benefit analyses mostly showed a positive benefit-cost ratio, which means that the analyzed planning’s appeared to be effective and value delivering [].

In setting the objectives, scope, and methods of participation, these aspects of the preparation of a participatory plan should be linked to specified, available resources. Additionally, linking planned participatory activities with a sustainable time frame is essential to keep opportunity costs at a level that does not exceed the added value of participation.

3.3.7. Awareness and Promotion

We have already mentioned various planning tools that serve as communication channels, enabling information sharing and collaboration in participatory planning. However, there is still a particular question of how to initially inform local society about the intention to draw up a development plan and in what form to invite them to become participants in the preparation of the plan in various forms.

The first situation is informing the population regarding the course and results of planning, for which the already mentioned communication channels of the local government can be used, such as public meetings, public hearings [,], but also the meetings of the city council [], which can be used as a tool for communicating development plans with the public. However, if the planning process should be participatory, involving different actors in different stages requires informing them and motivating them to participate []. Therefore, planning facilitators should decide in the pre-preparatory phase, after identifying the needs for involvement, how should they be invited, how to motivate actors to participate, and what communication tool they should use for promotion and information sharing []. Overview of communication tools is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overview of communication tools for ensuring participation.

If the local government wants to address specific stakeholders, within the model of “nomination of local experts” [], participation will be ensured through invitations to enter the planning process [] using available contacts, especially telephone and email addresses. Exceptional are the cases of small settlements that maintain contact lists for the population, or, as in the case of some innovative villages, even a system for sending municipal text messages [], which will enable sharing general information regarding important events.

The dissemination of general information regarding the planning process, as well as the effort to achieve a large participation in the open process, can also be ensured through its own blogs, podcasts, and webcasts [], or by using the websites of the municipality and its partners participation [].

The importance of using social networks for communication between local governments and the public is growing rapidly, while social networking tools can also be used to organize communication and work activities in participatory processes []. Municipalities that experiment with the use of integrated information platforms for broad civic participation in planning can also be used to disseminate information on progress and the opportunities for citizen involvement in planning [,]. Many studies, similar to our review, evaluate the introduction and use of e-technologies to disseminate information and ensure participation, however there are just few studies describing specific e-communication tools that are designed to implement existing forms of collaboration [].

4. Discussion

This article investigated the current literature that examined various aspects of participation management in strategic planning of local development, or local communities’ development. The main goal of this review was to evaluate the multi-dimensionality of participatory planning and individual settings that could be considered by local authorities for drawing up formal local development plans. Our paper reflects changes in planning practice in the context of the development of recent decades and transforms current knowledge into a framework for setting-up a participatory plan.

Our reflections suggest that a participatory plan can be a suitable tool for achieving effective participation management [,,,,,]. We only recorded mentions of a participation plan [], thus we expect that precise planning and management of participation is still probably not common practice in spatial, or community development planning in Europe. The studied literature have often found that local planners had no guideline to organize participation [,,,]. In the majority of EU countries, securing participation is a legislative requirement, however local-specific management of participation appears to be precondition of generation of value [,,,]. Localities and communities that recorded a significantly higher value added than the costs connected with participation are mainly those that created their own guidelines for participation management, based on unique local conditions [,,,]. This means that a universal guideline for participation does not exist, and never will. Participation in planning does not necessarily lead to increased efficiency, and it does not generate significant value in the conditions of each municipality [,,,,,]. The depth of participatory planning must reflect the capacity and resources of local government, public requirements, customs, and the structure of local values, size of the municipality, its demographic, cultural, ethnic structure, environ-mental values, degree of civic engagement, the strength of communities, and their engagement in local development.

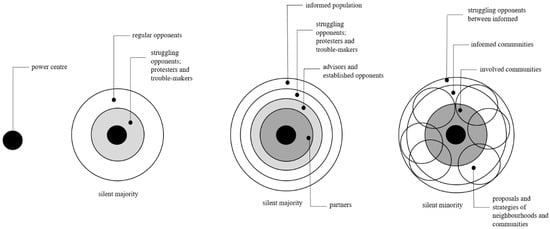

Today, we already have the answer to the question as to whether to climb the ladder of participation higher []—the goal of participation cannot be just to deepen it, if the participation should bring the desired results. Maier [] pointed to the need to express the multidimensionality of participation through a multidimensional model of participation patterns. We modify this model (Figure 1) to capture the major megatrends that affect planning in the second decade of the 21st century. It is, at the first hand, the internalization of society and technological advances that enable the development of highly specialized hybrid online platforms for communication and data collection [,,,]. Another trend is the shift of development planning to the sub-local level, which is associated with the progress of emancipation of local communities, which are becoming increasingly active and able to manage the development of a particular neighborhood []. The result of these processes is an experimental organization of planning at the neighborhood level, while preserving the decision-making powers of local governments. Therefore, the model of co-designing plans in a knowledge-based, engaged, local society already reflects how conflict and consensus building among citizens in the roles of partners, regular opponents, and protesters will move to the community level, while it can be expected that a minority will remain uninformed.

Figure 1.

Changes in the multidimensional model of participation from a totalitarian to a knowledge-based society.

In the reviewed case studies, we identified the individual steps and methods of organizing the participatory process and then integrated them into the areas of management that the participatory plan should follow. To answer research question 1, the entity that is responsible for management of strategic planning should look for answers for following questions before entering pre-planning phase: why to secure participation, who to include, to what extent, using which tools, from what resources, and how to address them. We recommend to practitioners to specify the objectives of participation, methods of stakeholder selection, competences and responsibilities of given stakeholders in individual phases of strategic planning, the usable tools and methods for communication and consensus building, specifying the resources provided to meet the objectives of participation, and information channels that can be used for the dissemination of information about possibilities of stakeholders to be involved in planning process. At the same time, it can be stated that there is a significant level of “mutual conditionality” between these settings; thus, links between managerial approaches, expectations, competence’s structure, resources, and communication channels should be established. To address the research questions 2 and 3, we detailed the possible configurations of organizational models of participation, costs that are connected with participation management and specified communication tools and decision support systems that can be utilized to facilitate inputs from participants. The identified configurations are summarized in Appendix B–participation matrix that should be understood as an auxiliary tool for planners and as a helpful tool for life-long learning of planners. The matrix can serve as a supportive decision-making tool for the initial configuration of local-specific participative plans.

This review is limited mainly in terms of narrow specification (participation set-up) of filtered knowledge from the examined studies and due to the focus on the pre-implementation phase of planning. Future research should focus, in particular, on assessing value creation through participation, with an emphasis on the less explored implementation phase of planning. There is a particular need to evaluate the effectiveness and value creation of community-based local development planning experiments, which, given the short experience, has not yet received sufficient scientific attention.

5. Conclusions

The participation of local stakeholders and communities on local development planning is increasingly recognized as a key for reaching balanced and sustainable local development. Participatory approaches to planning, or the co-designing of strategic plans generate value-added, not only in terms of improved and optimized goals, action plans, and concrete local development projects, but also in terms of building and strengthening of local communities, delivering local-specific innovations, reaching common positions towards key questions of further development, mutual communication, and learning. A participatory plan could be a particularly effective tool for local governments in the conditions of the transit economies of Central Europe, where new models of strategic planning are being tested without any instructions, mainly by trial and error. Without participation planning or the creation of local guidelines for participation in advance, the benefits of involving local actors in planning can be counterproductive. The case studies recorded examples of tokenistic, alibi, and overly open participation, which led to an escalation of conflicts between local stakeholders and authorities, the formulation of goals cut off from the real demands of local communities, or unrealistic action plans. Local planners should ensure that transaction costs arising from participation do not exceed the value-added that participation on planning generates. We only found a kind of good practice example in the field of attempts to secure the participation of the vast majority of locals in local development planning—it appears to be the recognition and empowerment of local neighborhoods and institutionalized communities in planning that is represented by community leadership.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and P.M.; methodology, M.H. and K.M.; validation, K.M. and O.R.; investigation, M.H., P.M., L.P., O.R.; resources, P.M. and L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., P.M., O.R., L.P.; writing—review and editing, M.H. and K.M.; visualization, M.H.; supervision, M.H., P.M.; project administration, K.M.; funding acquisition, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences under the project “Institutional environment as a vehicle of development policies in least developed districts”, No. 1/0789/18.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Appendix A. Overview of Empirical and Case Studies Identified in First Round of Draft in Scopus Database

| Authors | Article | Year | Cit. |

| Innes and Booher | Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century | 2004 | 640 |

| Brody et al. | Mandating citizen participation in plan making: Six strategic planning choices | 2003 | 187 |

| Moynihan | Normative and Instrumental Perspectives on Public Participation: Citizen Summits in Washington, D.C. | 2003 | 119 |

| Portney and Berry | Participation and the pursuit of sustainability in U.S. cities | 2010 | 99 |

| Ghose | The complexities of citizen participation through collaborative governance | 2005 | 77 |

| Meier | Citizen participation in planning: Climbing a ladder? | 2001 | 56 |

| Steinberg | Strategic urban planning in Latin America: experiences of building and managing the future | 2005 | 41 |

| Daniels et al. | Decision-making and ecosystem-based management: Applying the Vroom-Yetton model to public participation strategy | 1996 | 35 |

| Hutter et al. | Falling Short with Participation—Different Effects of Ideation, Commenting, and Evaluating Behaviour on Open Strategizing | 2017 | 28 |

| Roe | Landscape planning for sustainability: Community participation in estuary management plans | 2010 | 23 |

| Blomkamp | The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy | 2018 | 22 |

| Sisto et al. | Stakeholder participation in planning rural development strategies: Using backcasting to support Local Action Groups in complying with CLLD requirements | 2018 | 20 |

| Hopkins | The emancipatory limits of participation in planning: Equity and power in deliberative plan-making in Perth, Western Australia | 2010 | 18 |

| Pontrandolfi and Scorza | Sustainable urban regeneration policy making: Inclusive participation practice | 2016 | 15 |

| Martínez. | The Citizen Participation of Urban Movements in Spatial Planning: A Comparison between Vigo and Porto | 2011 | 15 |

| Zhuang et al. | The role of stakeholders and their participation network in decision-making of urban renewal in China: The case of Chongqing | 2019 | 14 |

| Batheram et al. | Successful participation methods for local transport planning | 2005 | 9 |

| Portschy | Community participation in sustainable urban growth, case study of Almere, the Netherlands | 2016 | 8 |

| Basinger and Peterson | Where you stand depends on where you sit: Participation and reactions to change | 2008 | 7 |

| Lederman | The People’s Plan? Participation and Post-Politics in Flint’s Master Planning Process | 2019 | 6 |

| MacAskill | Public interest and participation in planning and infrastructure decisions for disaster risk management | 2019 | 5 |

| Kinzer | Picking up speed: public participation and local sustainability plan implementation | 2018 | 4 |

| Frediani and Cociña | Participation as planning’: Strategies from the south to challenge the limits of planning | 2019 | 3 |

| Carra et al. | From community participation to co-design: “Quartiere bene comune” case study | 2018 | 1 |

| Shiehbeiki et al. | Public participation role in sustainable urban management by quantitative strategic planning matrix (QSPM) | 2014 | 1 |

| Watt and Purcell | The new champions of sustainable community participation? | 1997 | 1 |

| Bafarasat and Oliveira | Disentangling three decades of strategic spatial planning in England through participation, project promotion and policy integration | 2020 | 0 |

| Le Pira et al. | Competence, interest and power in participatory transport planning: Framing stakeholders in the “participation cube” | 2020 | 0 |

| Galiano et al. | Public participation in the process of improving quality of the urban frame | 2017 | 0 |

| Hidalgo and Morell | Co-designed strategic planning and agile project management in academia: case study of an action research group | 2019 | 0 |

| Alessandrini | Place-based strategic planning: The politics of participation | 2015 | 0 |

Appendix B. Participation Matrix

| How to Plan? | How to Coordinate Participation? | At What Stages of Plan Preparation? | Who to Include? | What Competencies to Provide? | To What Extent Should They Be Included? | What Forms of Communication/Networking to Use? | What Participatory Planning Techniques to Use? | How to Inform Society? |

| supplier approach | local government authorities | pre-planning consultations | citizens | get information | include “collaborators” and partners | public meetings, informal meetings | geographic information systems | leaflets, posters |

| creation of coordination and support bodies | institutions established by the local government | advisory teams and commissions | network analysis | local press | ||||

| traditional administrative approach | unelected managing or supporting body | data coll. for analytical part | representatives of state administration | present attitudes and comments | include “active citizens” | working groups | geoportals | telephone addressing |

| collection of ideas and project intentions | businesses, business associations, clusters | include “necessary” experts | interviews in households | participatory mapping | municipal sms | |||

| participatory strategic planning | elected managing or supporting body | formulation of the strategic part of the document | universities, private R&D institutions | formulate proposals | involve key actors in the territory | workshops | design thinking | local radio and television |

| on-going-monitoring | non–profit organizations | focus groups | mind maps, repertoire grids | own websites as well as partners | ||||

| co-design of a strategic plan | local government in collaboration with community leaders | draft preparation and optimization | environmental activists | participate in the formulation of drafts | balanced representation of actors | community forums | brainstorming | blogs, podcasts, webcasts |

| implementation | marginalized groups and their organizations | chat discussions on soc. networks | logical matrices | social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.) | ||||

| decentralized through local communities | ex-post evaluation and control | local grassroots partnerships and neighbourhoods’ representatives | participate in the approval | planning open to all | online meetings via team calls | opinion gauges and e-surveys | integrated local communication platforms | |

| specific local ICT communication platforms | transection walks |

References

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, K. Citizen Participation in Planning: Climbing a Ladder? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, K.E.; Berry, J.M. Participation and the Pursuit of Sustainability in U.S. Cities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2010, 46, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, J.; Fryk, L. Making School Children’s Participation in Planning Processes a Routine Practice. Societies 2021, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubita, A.; Libati, M.; Mulonda, M. The Importance and Limitations of Participation in Development Projects and Programmes. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2017, 13, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, S.B.; Kangare, M. What is participation? In Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) as a Participatory Strategy in Africa; Hartley, S., Ed.; University College London: London, UK, 2002; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lines, R.; Selart, M. Participation and organizational commitment during change: From utopist to realist perspectives. In Handbook of the Psychology of Leadership, Change, and Organizational Development; Lewis, R., Leonard, S., Freeman, A., Eds.; Wiley–Blackwell: London, UK, 2013; pp. 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mantere, S.; Vaara, E. On the problem of participation in strategy: A critical discursive perspective. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Making Plans that Matter: Citizen Involvement and Government Action. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisilino, F.; Monteleone, A. Designing Rural Policies for Sustainable Innovations through a Participatory Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C.; Mauborgne, R. Procedural justice, strategic decision making, and the knowledge economy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk, D.R.; Parham, D.W.; Porter, D.R.; Potapchuck, W.R.; Schukraft, S.W. Pulling Together: A Planning and Development Consensus-Building Manual; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Plan. Theory Pract. 2004, 5, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, T.; Brandt, E.; Gregory, J. Editorial: Design participation(-s). CoDesign 2008, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.D.; Godschalk, D.R.; Burby, R.J. Mandating Citizen Participation in Plan Making:Six Strategic Planning Choices. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAskill, K. Public interest and participation in planning and infrastructure decisions for disaster risk management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M. Landscape Planning for Sustainability: Community participation in Estuary Management Plans. Landsc. Res. 2000, 25, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, K. Getting involved in plan-making: Participation in neighbourhood planning in England. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2016, 35, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.; Lamers, M.; Van Zeijl-Rozema, A.; Dieperink, C. Conceptualising joint knowledge production in regional climate change adaptation projects: Success conditions and levers for action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 18, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkamp, E. The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, I. An Introduction to Co-Design; Knode: Sydney, Australia, 2012; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, M.; Manschot, M.; De Koning, N. Benefits of Co-design in Service Design Projects. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank, L.; Coupem, G.; Hennessy, D. Co-Design: Fundamental Issues and Guidelines for Designers: Beyond the Castle Case Study. Swed. Des. Res. J. 2016, 10, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, M.A.; Leendertse, W.; Arts, J. Conditions for Co-Creation in Infrastructure Projects: Experiences from the Overdiepse Polder Project (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovan, W.R.; Murray, M.; Shaffer, R. Participatory Governance: Planning, Conflict Mediation and Public Decision-Making in Civil Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Basinger, N.W.; Peterson, J.R. Where you stand depends on where you sit: Participation and reactions to change. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2008, 19, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, B.; Wegelin, E. Guiding Cities: The UNDP/UNCHS/World Bank Urban Management Programme; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2001; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M. A strategic approach to participatory development planning: The case of a rural community in Belize. PLA Notes 1995, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zérah, M.H. Participatory Governance in Urban Management and the Shifting Geometry of Power in Mumbai. Dev. Chang. 2009, 40, 853–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Frels, R. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal Andcultural Approach; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2016; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.C.; Sipe, N.G.; Gleeson, B.J. Performance-Based Planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 25, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]