Abstract

Student-centered learning (SCL) has been acknowledged and supported by research as very important for helping students develop life-long independent learning and transferable skills. Yet the implementation of SCL in European higher education has been patchy where experts in the field call for the need for a framework that could guide higher education institutions (HEIs) in designing and implementing SCL. This paper aims to fill in this identified gap by reflecting on the basic literature and social theory to propose the reflexive GOAL (Goals (vision and objectives), Organization (structures), Actions (immersion into structures and actions), and Learning a culture (instilled through reflexivity)) framework for the implementation of SCL in higher education in its broader sense to encompass elements from in-class learning to extra-curricular and community engagement.

1. Introduction

“[T]he implementation of SCL in practice is lacking”[1]

In her keynote speech at 20th anniversary of the Bolonga Process, Klemenčič [2] cites the above quote from a forthcoming publication by the European Student Union’s researchers, which highlights that student-centered learning (SCL) has not been fully developed and implemented at higher education institutions (HEIs), despite its institutionalization ten years earlier and research evidence showing that SCL improves educational outcomes, such as performance, motivation, team work skills, and so forth. Along similar lines, Sundberg et al.’s [1] study “Bologna with student eyes” showed that SCL has been implemented in many countries, but implementation has been very slow and there is no consistency across states. The study concluded that students were still not adequately included in the process of curriculum development, learning had not become as individualized as it should, and the involvement of students in quality assurance and other extra-curricular activities could have been much more enhanced. Klemenčič has outlined a number of reasons why SCL has not been fully implemented. These are: lack of widely accepted definition and framework, misconceptions about what SCL entails, and how it helps. Interestingly, Geven and Santa [3] had pointed out additional factors such as poor institutional policy, lack of expertise, inadequate budget, and negative attitudes by institutions and teachers.

It seems that the main reason for the patchy implementation of SCL relates to the absence of SCL culture and the lack of a holistic institutional plan for implementing SCL through a gradual process of involving all relevant stakeholders and of assuring the quality of implementation. It is this gap that this paper aims to fill in by conceptualizing and describing the GOAL framework. GOAL stands for Goals (vision and objectives), Organization (structures), Actions (immersion into structures and actions), and Learning a culture (instilled through reflexivity). This is not to argue that there no other models or guidelines and tips with regard to implementing student-centered learning at a higher education institution’s (HEI) level in Europe. For example, the European Student Union published a detailed pathway in order to help HEIs and teachers to transform their practices to reflect SCL [4]. Sundberg et al. [1] presented a series of recommendations on how to implement SCL by all possible stakeholders, while Klemenčič [2] outlined indicators for SCL at both the institutional and program levels. However, the GOAL framework does not include guidelines, recommendations for teachers, and descriptions of best practices. Instead, it is a simple and generic framework, consisting of principles and structures, which could easily be adjusted to each HEI’s needs and capacity without being prescriptive so to allow flexibility and, as a result, implement SCL successfully. The framework is applied at various levels from the establishment of vision and objectives to the achievement of student-centeredness. The process is reflexive and the ultimate goal is to create a long-standing student-centered culture, which will result in life-long student-centeredness that enables students to acquire transferable skills from in-class knowledge to community engagement and service learning. Before I describe the GOAL framework, let me first briefly unpack the history, definition, and importance of SCL in European HEIs.

2. Student-Centered Learning (SCL): Its Importance and Implementation

Initial discussion of the concept of SCL is dated back to the early 20th century. The concept was further developed in the 1930s with the work of Dewey [5] and in the 1950s with that of Rogers [6] who incorporated the term in a broader theory of education [4]. In general, the concept of SCL reflected the principles of constructivist theory, which referred to the process where learners learn by constructing knowledge through engagement in an activity [4]. SCL was not only thought about and expanded upon at a theoretical level, but it was influenced socio-politically and scientifically [7,8]. More specifically, student protests in the late 1960s against universities, which attracted only middle class students sent a message that students had or should have more power, while new evidence in pedagogy indicated that learning through didactic teaching was rather ineffective [8]. Growing diversity in university student bodies resulting from the increasing number of students from different cultures and different exposure to educational systems exerted more pressure on making changes in pedagogy in order to better reflect the needs of students to develop as independent learners.

SCL was institutionalized and further promoted to HEIs with the Bologna Process in 2009 and during the Bucharest Ministerial Conference in 2012 [8]. Furthermore, in 2015, SCL was officially recognized as a quality criterion under Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG), and HEIs are now expected to show evidence of meeting this quality criterion.

Throughout its history, the concept of SCL has been defined many times and in different ways. To add clarity, a European-funded project entitled “Time for a New Paradigm in Education: Student-Centered Learning” (T4SCL) [4] concluded a comprehensive definition after evaluating the input of various stakeholders. According to the T4SCL definition, SCL means:

“Student-Centered Learning represents both a mindset and a culture within a given higher education institution and is a learning approach which is broadly related to, and supported by, constructivist theories of learning. It is characterized by innovative methods of teaching which aim to promote learning in communication with teachers and other learners and which take students seriously as active participants in their own learning, fostering transferable skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking and reflective thinking”.

Based on this definition, students are at the center of learning and all the relevant parties work together in partnership to help students develop and acquire skills that are transferable (i.e., to future studies, career, etc.). Therefore, I would like to expand on the definition above to add that learning is not only academic, but it also refers to students’ social and psychological development as well as to students’ professionalism, sense of safety and belonging, giving and receiving feedback, participation in governing bodies, extra-curricular and community engagement, and so forth. This means that, at institutional level, SCL should not only involve teachers and students but should reach out to encompass more players, such as administrators, HEIs, and the community [2]. This expanded definition is the backbone of the GOAL framework in this paper.

The T4SCL project explored the relevant theory, collected feedback from teachers and students, and generated nine principles in order to achieve SCL successfully [4]. These are: Principle I. Continuous feedback and reflexivity: students, teachers, and the decision-making bodies in HEIs have to be in a constant dialogue and review existing practices for further enhancement. Principle II: SCL is not “one size fits all”: HEIs have to be flexible and adjust SCL to their objectives, needs, and capacity. Principle III. Different students learn in different ways: the literature shows that there is a variety of learning needs in the sense that some learn by reading books, others by doing, others by discussing in groups, and so forth. Principle IV. Different students have different needs and interests: this principle touches on the issue of social and cultural diversity as some students are interested more in cultural and community activities while others in sports and social events. Principle V. Having choice helps learning: having choice is important because many students like learning different things and not only what is communicated to them in class or in books. Principle VI. Students have different backgrounds and experiences: this is important for teachers and HEIs to bear in mind so that the learners’ background is gauged at the beginning of the program and teaching/ learning opportunities can be adjusted accordingly. Principle VII. Students should have control over their learning: this is a critical principle in student-centered learning. Students should be understood and treated as partners in shaping their learning. Principle VIII. SCL should not be about telling (i.e., lecturing) but about enabling and empowering: students should be given the opportunity to think critically, analyze, reflect, synthesize, and solve problems. Principle IX. Learning should not be imposed: The learning process should not be exclusively decided by teachers. Instead, students and teachers should cooperate in order to understand one other and result in synergies. This is a central principle in student-centeredness whereby learning is created through interaction. In general, these principles highlight the importance of active learning, diversity, individualized education, community engagement, and partnership. A critical question here is, “Does applying any of these SCL principles result in enhancing student learning?”

There is research evidence to show that SCL practices are associated with positive learning outcomes [2]. More specifically, a series of studies have shown that SCL has helped students to be more involved and to achieve better academic results [7]. Moreover, studies have shown that when students’ needs are met more holistically (academic, social, physiological, etc.), they tend to miss fewer classes, are more engaged and achieve higher academic scores, are less likely to drop out, and are better prepared for employment [9]. In support, empirical evidence points out that active learning, which is one of the main principles of student-centeredness, is linked with lower rates of failure and better performance [10,11], students develop other transferable skills, such as learning how to learn, problem-solving, engagement, and team-work [12,13,14,15], while students appear more motivated and less likely to be absent [11]. In addition, active engagement in learning helps with retention of information. More specifically, retention of information after twenty-four hours is the lowest through didactic lectures, whereas learners remember much more by doing or teaching others [16]. This does not mean that lectures have become obsolete. Instead, they still remain important for providing the necessary scaffolding to students in order to understand the relevant academic material and expand their knowledge through other sources. On this note, Hattie et al. [17] highlighted that lectures can work as activators and guides and can incorporate elements of active and student-centered learning. Richardson [18] urged for “don’t dump didactic teaching; fix it” by incorporating elements of active learning [19].

In addition to the evidence above, the European Student Union has published a report that outlined a number of benefits for students, teachers, and HEIs [4]. To elaborate, students’ sense of belonging in the academic community is strengthened resulting in becoming more engaged. Furthermore, students are likely to feel more motivated to learn, to become more independent and responsible learners, and to find how learning best suits their needs and interests. SCL benefits teachers as well largely within the context of staff development. That is, teachers learn new ways to teach; they adjust to diversity; they make their courses more challenging, interesting, and applied to real life situations; they become more motivated and engaged and develop as student-centered teachers; and they learn about educational principles and enhance their skills. Benefits are not confined to students and teachers, but they reach out to encompass HEIs. That is, the quality of teaching is developed, student satisfaction is improved, retention rates are better, more students are attracted, and a life-long culture of learning development is established.

Apart from the suggested benefits above, SCL’s helps students develop other important transferable skills such as working collaboratively with other stakeholders. That is, one of SCL underlined principles is partnership between HEIs and students for the development of learners who should not be understood and treated as customers [20] Research evidence shows that consumer identity is associated with lower academic performance because students are less likely to be involved in their learning. In addition, customers do not participate in the processes of developing a product or service and therefore cannot contribute substantially to the quality of the final outcome [20]. Instead, partners do contribute to improved quality, and they work together in order to create synergies, which can benefit all of the partners involved; in higher education, these are students, teachers, administrators, and decision-making bodies in HEIs. The Higher Education Academy in the UK has published a guide on how partnership with students can be achieved, highlighting its importance for both students and HEIs [9].

In addition to the studies above which pinpoint that SCL is linked with positive academic learning outcomes, there is evidence to suggest that extra-curricular engagement enhances the student experience. Drawing information from thirteen universities in the UK, Thomas et al. [21] found that social engagement and belonging were among the key factors contributing towards retention. Foster et al.’s [22] study at Nottingham Trent University found that more than 30% of students considered not continuing with their studies and explained that poor sense of belonging was the driving force. With regard to university outreach and community engagement, the effectiveness of service learning, and the ensued benefits for students and universities have been well-documented in the literature [23,24,25,26]. For example, Gregorová et al.’s [23] study showed that service-learning enhanced students’ key competencies, namely communication skills, leadership, cooperation with others, cultural understanding, responsibility, learning, problem-solving skills, development of critical thinking, and so forth. An earlier meta-analysis of 63 studies by Celio et al. [25] demonstrated similar results.

Despite the fact that SCL improves the learners’ experience, it would be interesting to see how it has been implemented by European HEIs. In a recent report by the European Student Union (ESU) [8], a survey form twenty countries showed that 74% of the students who responded were not familiar with SCL. The same study showed that even though students identified a change in their universities’ narratives about SCL they thought that these narratives did not match practical changes. For example, student-centered methods have been introduced, yet lectures remain the predominant method. A large percentage of students felt that they were not consulted for curriculum development purposes. The ESU’s study indicated that things have moved towards a more SCL mode, but there is still a lot to be done. The lack of systematic implementation by HEIs has been acknowledged by Klemenčič [2] who emphasized the lack of a universal definition of SCL and framework of implementation. An earlier report by ESU also highlighted inadequate policies as well as lack of enthusiasm from academic staff [4]. Sundber et al.’s [1] study showed that based on students’ perspectives the implementation of SCL by HEIs is slow and carried on clarifying that “as a relatively recent addition to the ESGs, it seems SCL still hasn’t achieved full recognition and equal importance.”

It is this gap that this paper is filling in by proposing the reflexive GOAL framework for a successful establishment and long-term implementation of SCL at a HEI level. In order to achieve SCL at a HEI level, people need to believe that it is useful and beneficial and act upon it accordingly; something that can be established by the creation of relevant culture. Below, I explain how the GOAL framework has been conceptualized.

3. Conceptualization of the GOAL Framework

This section explains in detail that the GOAL framework has been conceptualized on the basis of the concept of culture, the social theories of functionalism and symbolic interactionism and how these apply to an institution, and what it takes to create a culture and establish it in a community of people. The conceptualization of the GOAL framework has also been guided by the expanded definition of SCL, as presented under Section 2, which reaches beyond academic learning to include extra-curricular and social engagement as well as participation in governing bodies of HEIs and development through feedback. This section concludes with a critical reflection on the GOAL framework, outlining limitations, and suggestions for future research.

3.1. Theoretical Foundations of the GOAL Framework

There are many definitions of culture in the literature. A popular one comes from the anthropologist Tylor [27] and clarifies that “Culture, or civilization, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” This definition points out a number of characteristics of culture. That is, culture is learned, it is shared, and it is interconnected in the sense that it results from people’s interaction with each other. In addition, culture consists of symbols that people share in order to communicate and act, and it is not static but dynamic and changing [28]. An important factor of establishing a culture is people constructing boundaries around their community and groups of insiders and outsiders [29]. This entails engagement of the members of the community with values and practices.

Apart from the concept and characteristics of culture, the theories of functionalism and symbolic interactionism have been used as a guide to the construction of the GOAL framework. Functionalists understand culture as a unified system consisting of interconnected parts, which function together in order to achieve a common goal [30]. Symbolic interactionists focus more on people, how they understand their world, and how they create culture by interacting with each other [31]. These theories are important because GOAL aims to be implemented in a micro-society: that of a higher education institution (HEI).

As the GOAL framework is designed for an institution or organization, it is important to consider how the concept of culture and cultural characteristics could apply at an institutional level. To address this question, Martins and Martins’ [32] approach to the creation of culture in an organization was used. More specifically, Martins and Martins [32] reviewed the literature in order to create an organizational culture on creativity and innovation. Before determining the factors that would establish a mindset for creativity and innovation, they found that the basic characteristics for creating a culture in an organization are: vision and mission, customer focus, means to achieve the objectives, management process, employee needs and objectives, interpersonal relationships, and leadership. These cultural characteristics in an organization are reflected on the characteristics at a community level in the following ways. First, employees can learn new ways of thinking and practice through training and through long-term immersion into institutional lifestyle. Second, shared culture in an organization relates to common vision, mission, and objectives. Third, interpersonal relationships are fundamental for establishing a new culture and symbols, common understanding, or regulations and process and facilitating building relationships. Fourth, elements of culture are interconnected. This means that all staff and departments are interconnected and develop synergies in order to achieve a common goal. Interconnectedness can be achieved only through the establishment of symbols and procedures, but also when the appropriate means are offered and good management and leadership are available in order to support, adopt, and act upon new values and regulations. Other scholars came up with similar principles. For example, Sarros, Cooper, and Santora [33] relied on a functionalist perspective and came up with principles such as vision, role model, support, acceptance, and performance expectations in order to achieve an effective relationship between leadership, organizational culture, and climate for innovation. Naranjo-Valencia, Jiménez-Jiménez, and Sanz-Valle [34] generated similar recommendations for creating a new culture for innovation.

The GOAL framework has also been informed by Klemenčič’s [2] guidelines presented in her keynote speech during 20th anniversary of the Bologna Process. Klemenčič clarifies that “in short, the student-cantered learning and instruction ecosystems in EHEA is an interactive system of multiple elements supporting the design and the implementation of study programs and courses based on SCLI [student-centered learning and instruction] methodology. It is premised on the existence of SCLI institutional policy, rules, regulations and incentives which reflect the collective values and norms on SCLI. This ecosystem allows for interactions between the multiple and intertwined learning communities—within each course, course-based projects, advising or peer tutoring groups, study programs, multiple related study programs, research and entrepreneurship labs, etc.—that comprise of internal stakeholders—students, teaching staff, relevant administrators, researchers, etc. as well as their educational partners from outside communities, i.e., industry, government, non-profit organizations, etc.”. Basically Klemenčič has called for the need for the establishment of multiple components, values and norms, institutional policy and regulations, incentives, and involvement of key players, such as teachers, students, administrators, and community organizations. All these should be interconnected in order to construct an SCL “ecosystem”.

3.2. The Reflexive GOAL Framework

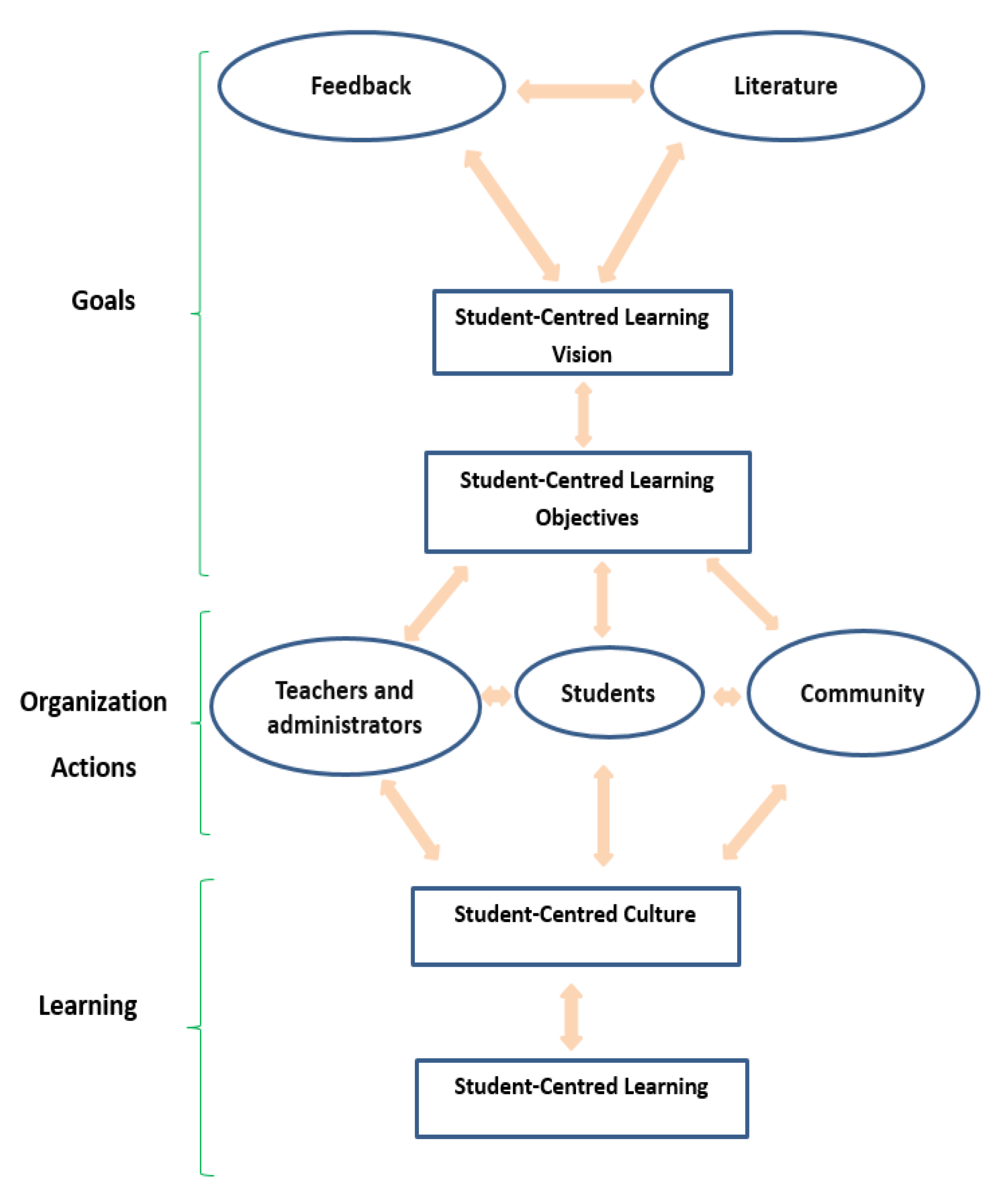

Based on social theories of culture, the underlined features of a community and institutional culture, the expanded definition of SCL, and Klemenčič’s guidelines, I propose the reflexive GOAL framework for creating a student-centered culture and, as a result, student-centered learning from class to community engagement in European higher education. GOAL stands for Goals, Organization, Actions, and Learning. These are mainly the principles for achieving SCL and each of this principle encompasses specific players and structures (Figure 1). These could also work as stages in chronological order in the sense that Goals need to be finalized first, before actions are structured under Organization, Actions are taken, and Learning is instilled. Let me explain each principle and stage separately.

Figure 1.

The reflexive GOAL framework at a higher education institution (HEI) level.

Goals refer to establishing a common vision and objectives to be achieved by all relevant stakeholders. A critical question here is that Goals should be shared. In order to achieve this, any vision or objectives should not be formulated at the top and implemented by stakeholders at the bottom. Instead, they should be generated by stakeholders at the bottom and officially adopted by the management and leadership of the HEI so that the stakeholders who are expected to implement SCL practice actively participate in the process. What should be top-down is the instruction and need to change people’s mindset and practice. Goals as a principle is very important because it is where the learning of a new culture begins. As per Figure 1, shared goals could be achieved by first listening to the people who are expected to implement student-centeredness and understand their perspective, suggestions, and needs. These are students, teachers, administrators, and community organizations such as industry, governmental agencies, NGOs, associations, and so forth. In addition, the relevant literature should be consulted so that any objectives are evidence-based. More specifically, research evidence on the usefulness of SCL, what other HEIs have done, whether SCL practices (e.g., acting upon student feedback) enhances quality, student satisfaction, and so forth. From feedback and information from the literature, vision, and broad objectives could be generated. The objectives at this stage should be at the HEI level and should be broad. From these broad objectives, more specific objectives should be generated at an individual level under the next principle.

Organization (structure) is about the process of expanding form the previous principle and structuring actions in a way to reflect the broad vision and the objectives. The four key players (students, teachers, administrators, community organizations) need to adjust their actions in a way to accord with the agreed objectives and visions. In other words, they are expected to change their institutional lifestyle. Since culture is learned, Organization further enhances the learning of a new culture. This is a challenging endeavor, which requires good structuring and time. This can be achieved through a number of steps. First, teachers, students, administrators, and relevant community organizations should be trained in SCL principles and practices. They have to have a clear idea of what it entails and how it can be achieved. Second, these four players should formulate their own objectives in how to achieve student centeredness. Third, HEIs should have a in place mechanisms or structures of quality assurance and development. Apart from types of assessing students as active and independent learners, for teachers and administrators, these mechanisms could include student experience and satisfaction survey, vacancies calls and recruitment of new staff, job descriptions, peer review, appraisals, promotion, audits, feedback and trainings, awards (e.g., HEI awards, student-led awards, and community awards), and so forth. All of these mechanisms or structures should include individual SCL objectives, how they have been met, and what support is required for stakeholders to better meet or exceed these objectives. Fourth, the four key players should communicate with each other through various structures (committees, meetings, open fora, etc.) in order to understand and work as partners for enhancing student-centeredness and achieving the HEI’s and their individual student-centered goals. Organization is fundamental for learning the SCL culture because learning a culture requires long-term immersion. Therefore, the structures or mechanisms described above will function as contexts where stakeholders will immerse themselves; where they will engage with SCL more and more. Over time, these structures could help making SCL thinking and actions like second nature in the sense that they are all relevant stakeholders in an HEI and outside could spontaneously activate an institutional SCL lifestyle. The actual immersion is taking place under the next principle.

Actions directly relate with the Organization in the sense that they result from the structures in place. To elaborate, students should take actions and work in partnership with teachers, administrators and community organizations, be more active learners, give constructive feedback, participate in governing bodies, engage with student-centered awards, engage in extra-curricular activities, immerse themselves into service learning opportunities, self-reflect, and develop as life-long learners with transferrable skills. Teachers should be in a constant communication with students, administrators, and community organization, adopt SCL techniques in the courses, develop in response to student feedback, engage with training, appraisals and peer reviews, embrace and participate in student-centered awards, and self-reflect and refine their personal objectives. By the same token, administrators should work constructively with all players, provide student-centered support, have training, develop in response to student feedback and appraisals, and engage with relevant awards. Finally, community organizations should provide all necessary opportunities for community engagement and service learning. In general SCL Actions by all players should reflect HEI’s Goals (vision and objectives) and take place in and supported by Organization (official structures).

Learning is the final principle and latest stage of achieving SCL. It is when the new institutional lifestyle or student-centered culture is instilled. Learning is going to be achieved provided that all previous principles and stages are put in practice over a large period of time. The backbone for instilled Learning is constant actions or long-term immersion into the new lifestyle and revision of the whole process. This means that actions systematically and consistently reflect vision and objectives, are supported by official structures, and are improved through constant reflection, training, and rewarding. Therefore, instilled Learning of this new culture and doing SCL cannot be achieved without reflexivity. Reflexivity is a popular term in social sciences, and it has been used in theories (e.g., ‘risk society’, ‘structuration’) [35,36] and in research methodologies (e.g., qualitative research) [37]. Reflexivity in the context of GOAL means that there should be a constant dialogue among all principles, players, structures, and stages. Constant dialogue means that each component of the framework informs and supports each other in a life-long learning process where objectives, actions, and support mechanisms are revisited in order to optimize student centeredness: hence, “the reflexive GOAL framework”.

The GOAL framework reflects the characteristics of culture and the theories of functionalism (interconnectivity and functionality) and symbolic interactionism (interaction and common understanding), as outlined earlier in this paper. However, there is a missing link to ensure interconnectivity and functionality. These principles and their ensuring players and structures cannot be put in place on their own and start functioning. A coordinating body or department within HEIs is necessary to take the overall responsibility to set it up, monitor, and evaluate the whole project.

3.3. Critical Reflection on GOAL

The GOAL framework has been prepared to fill in an identified gap in the implementation of SCL at European HEIs even though it was institutionalized in 2009 during the Bologna Process and was included as quality criterion in the European Standards and Guidelines (ESG) in 2015 [38]. GOAL consists of specific principles, stages and relevant players and structures. That is, Goals (vision and objectives), Organization (structures and individual objectives), Actions (immersion into actions and structures), and Learning (culture instilled through reflexivity). Apart from its principles and structures, GOAL symbolically resembles the “goal” to fully implement SCL in HEIs.

GOAL was triggered by evidence showing that constructivism approaches and active learning help learners develop transferable skills. It has also been influenced by studies describing student perceptions of SCL methods at universities. In addition to the evidence used as a baseline for the need for a comprehensive framework, GOAL was informed by social theory in terms of creating a culture in a community or an organization, and it involves all relevant stakeholders, such as HEI, teachers, students, administrators, and community organizations. It is based on simple principles, and it is generic enough so that it can be implemented by any HEI. As Klemenčič [2] has pointed out “SCLI methodology cannot be copy-pasted from one study program to another nor from one course to another.” Therefore, the GOAL model allows flexibility and creativity within programs and courses.

However, conceptualization of GOAL has some limitations. It would benefit from studies showing how teachers and administrators in European HEIs and community stakeholders understand the implementation of SCL methods. To the best of my knowledge, such studies are lacking, possibly because implementation of SCL has been slow for the reasons explained earlier in the paper. Longitudinal insights by teachers, administrators, and community institutions would help better understand how all stakeholders would accept and embrace SCL or how SCL could be better designed and implemented.

Beyond the conceptual limitations of GOAL, there is a number of factors that could potentially make the framework challenging to implement. First, there is a diversity of teaching styles and experiences, which need to be addressed. There are teachers who are not used to active learning techniques or were immersed into a more teacher-centered style and philosophy in the past. This means that some teachers may not be willing to introduce more active learning in their teaching or design and implement service learning course components and work with relevant community organizations. In this case, teachers might find useful research evidence that shows the educational benefits of SCL and training in how they can achieve this in their teaching. The same applies to administrators who may have difficulties to adopt a more student-centered approach, improve on the basis of feedback, and communicate with students sensitively. Administrators who are not used to student-centered organization lifestyle might find research evidence useful and benefit from training. Second, implementation of SCL might not be straightforward across all disciplines. There might be challenges or the SCL methods may differ between, for example humanities and physics. On this note, teachers should be involved in the decision making and trained and supported in order to revise their courses or modules in a way that would make SCL relevant but also successful. Third, students have different learning styles and some may be more used to and prefer a more teacher-centered way. HEIs may find this quite challenging especially if they have a culturally diverse student body. This can be overcome with good signposting before students are at the admissions stage and training as early in their studies as possible. Formative active learning exams would help students better familiarize themselves with a new learning style and put any anxieties at ease. Fourth, HEIs may not have the necessary resources—such as technology and budget for training—time, and experience to collaborate effectively with community organizations in order to fully implement SCL practices. This can be overcome through long-term and careful planning and the recruitment of people who have experience in service learning and have worked with community organizations for educational purposes before.

Despite the challenges and limitations, the reflexive GOAL framework could be implemented successfully if adjusted carefully to each HEI’s needs and capacity, and more importantly, if enough time is allowed. In addition, the GOAL framework could open new directions in research by evaluating the framework as a whole and eventually modifying it on the basis of empirical evidence. The framework could be evaluated in relation to student performance, satisfaction, retention, preparedness for employment and employability, and staff satisfaction and development. Finally, more studies are needed to explore how relevant stakeholders understand the implementation of SCL methods and whether they share a similar understanding with students.

4. Conclusions

There is evidence to suggest that student-centered learning (SCL) helps students develop as independent learners with transferable skills. Although SCL has a long history, it was institutionalized in 2009 at Bologna Process and included as a quality criterion in the European Standards and Guidelines in Higher Education in 2015, its development at HEIs falls short of expectations. To fill in this gap, this paper proposes the reflexive GOAL framework, which makes provision for the role of multiple components that are interconnected and work together in a reflective process for achieving student-centered learning from the university class to community engagement and service learning.

This paper makes an important contribution to the SCL literature and provides a comprehensive framework, which is theoretically informed. The GOAL framework has been influenced by research evidence about the importance of SCL practices, and it has been heavily informed by an expanded definition of SCL, which suggests that SCL is not only about academic learning, but it reaches out to encompass transferable skills through other contexts such as social and community engagement and service, professionalism, psychological wellbeing, and so forth. Such a definition indicates the need to approach student learning and development holistically. Beyond the definition and research evidence, the GOAL framework could not work if it did not provide a pathway of creating an SCL culture among the stakeholders expected to implement it. Based on the theories of functionalism and social interactionism and relying on the concept of culture, how it is created and practiced, a culture of SCL in a HEI begins with common goals, actions, and structures, and it is instilled and ingrained in people’s daily practice through long-term reflexivity. The GOAL framework provides a complete pathway from definition, to evidence, and to establishment of a culture, which could potentially be implemented by any HEI.

Author Contributions

C.S.C. conceptualized, wrote, revised and finalized the content of the paper. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sundberg, C.; Koppel, K.; Schwitters, H.; Patricolo, C.; Gajek, A.; Šušnjar, A.; Příhoda, F.; Hovhannisyan, G. Bologna with Student Eyes: The Final Countdown. European Student Union. Available online: https://www.esu-online.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BWSE-2018_web_Pages.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Klemenčič, M. Successful Design of Student-Centered Learning and Instruction (SCLI) Ecosystems in the European Higher Education Area. A Keynote at the XX Anniversary of the Bologna Process. Available online: http://bolognaprocess2019.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/02-keynote_Klemencic.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Geven, K.; Santa, R. Student Centred Learning: Survey Analysis Time for Student Centred Learning. European Student Union. Available online: https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/highereducation/2010/Student%20centred%20learning%20ESU%20handbook.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Attard, A.; Di Iorio, E.; Geven, K.; Santa, R. Student-Centred Learning: Toolkit for Students, Staff and Higher Education Institutions. Eur. Students’ Union (NJ1) 2010. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED539501.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Macmillan: New York, NY, SUA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory; Constable: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Kaput, K. Evidence for Student-Centered Learning. Edu. Evol. 2018, 5–22. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581111.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Todorovski, B.; Nordal, E.; Isoski, T. Overview on Student-Centred Leaning in Higher Education in Europe: Research Study; European Student Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Healay, M.; Flint, A.; Harrington, K. Engagement through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, K.; de Brabander, C.J.; Martens, R.L. Student-centred and teacher-centred learning environment in pre-vocational secondary education: Psychological needs, and motivation. Scand. J. Edu. Res. 2014, 58, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushlihuddin, R. The effectiveness of problem-based learning on students’ problem solving ability in vector analysis course. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 948, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, N.P. Effectiveness of team-based learning methodology in teaching transfusion medicine to medical undergraduates in third semester: A comparative study. Asian J. Trans. Sci. 2017, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reif, G.; Shultz, G.; Ellis, S.A. Qualitative Study of Student-Centered Practices in New England High Schools; Nellie Mae Education Foundation: Quincy, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Asoodeh, M.H.; Asoodeh, M.B.; Zarepour, M. The impact of student-centered learning on academic achievement and social skills. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.A. How the Brain Learns to Read; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, SUA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D. Don’t dump the didactic lecture; fix it. Adv. Physiol. Edu. 2008, 32, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. Active learning: An introduction. ASQ High. Edu. Brief 2009, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce, L.; Baird, A.; Jones, S.E. The student-as-consumer approach in higher education and its effects on academic performance. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1958–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Hill, M.; O’Mahorny, J.; Yorke, M. Supporting Student Success: Strategies for Institutional Change—What Work? Student Retention & Success Programme; Paul Hamlyn Foundation: London, UK; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E.; Lawther, S.; Hardy, C.; Kirby, R.; Molineaux, P. Nottingham Trent University’s Welcome Week: A Sustained Programme to Improve Early Social and Academic Transition for New Students. In Compendium of Effective Practice in Higher Education Retention and Success; Andrews, J., Clark, R., Thomas, L., Eds.; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2012; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorová, A.B.; Heinzová, Z.; Chovancová, K. The Impact of Service-Learning on Students’ Key Competences. Int. J. Res. Serv.-Learn. Comm. Eng. 2016, 4, 367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Sandaran, S.C. Service learning: Transforming students, communities and universities. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 66, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celio, C.I.; Durlak, J.; Dymnicki, A. A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. J. Exp. Edu. 2011, 34, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, C.A. Is service-learning effective? A look at current research. Serv. Learn. Persp. Appl. 2008, 1–11. Available online: http://fresnostate.edu/craig/depts-programs/mktg/documents/Is%20S.L.%20Effective-.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Moore, J.D. Visions of Culture: An Annotated Reader (ed); Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yoost, B.L.; Crawford, L.R. Fundamentals of Nursing-E-Book: Active Learning for Collaborative Practice; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.P. Symbolic Construction of Community; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J.C. The Meanings of Social Life: A Cultural Sociology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Symbolic Interactionism and Cultural Studies: The Politics of Interpretation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, E.; Martins, N. An organisational culture model to promote creativity and innovation. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2002, 28, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarros, J.C.; Cooper, B.K.; Santora, J.C. Building a climate for innovation through transformational leadership and organizational culture. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 2008, 15, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Valencia, J.C.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Studying the links between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies. Rev. Latinoam. Psicolog. 2016, 48, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. From industrial society to the risk society: Questions of survival, social structure and ecological enlightenment. Theory Cult. Soc. 1992, 9, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG). Available online: https://enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ESG_2015.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2020).

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).