Abstract

Using American General Social Survey data from 1994 to 2018, this paper examines how Americans of different racial backgrounds perceive their past intergenerational mobility and their, and their children’s, prospects for future mobility, before, during, and after Barack Obama’s presidency. We find that White Americans are generally less positive than Black and Latinx Americans about mobility, especially their children’s mobility prospects. However, racial gaps in optimism widened considerably during the Obama presidency, due to a significant decline in White respondents’ perceived mobility. A more detailed analysis of White respondents’ views by levels of racial resentment and political partisanship shows that the Obama-era dip among White respondents is concentrated among those who are racially resentful and among Republican voters, two groups that substantially overlap. For these two groups, perceived future prospects for their and their children’s mobility increased again during the Trump administration. Black and Latinx respondents’ perceptions of mobility are stable across all earlier presidential administrations, but decline somewhat with the Trump presidency.

1. Introduction

In 2008, the election of Barack Obama as the first Black American president occurred simultaneously with a deep economic crisis. In many circles, considerable hopefulness—about both an economic turnaround and race relations—accompanied Obama’s election, but we also know that racial resentment among White Americans depressed Obama’s electoral support at that time [1], and grew over the course of his administration [2]. Eight years later, Donald Trump’s electoral upset made this latent racial resentment far more visible.

This paper examines how Americans of different racial backgrounds perceived their own past social mobility and their and their children’s future prospects for mobility over these years, including the extent to which these perceptions can be explained by objective differences in socioeconomic trajectories. Though analysts of political behavior often consider voters’ general feelings of economic optimism and perceptions of recent changes in economic circumstances, our focus is on the longer and especially intergenerational view: how people assess their own position compared to that of their parents and how they perceive their own and their children’s chances for upward mobility. We believe that perceptions of opportunity and intergenerational mobility are particularly worthy of investigation, given their ideological importance in the United States.

We document several key findings. The first is that, in the historical period under study, and especially during Obama’s presidency, non-White respondents came to have a more positive view than White respondents about mobility. Racial gaps in perceived mobility appear to narrow again somewhat upon conclusion of Obama’s presidency. Our second key finding is that, among White respondents, political partisanship and racial resentment explain the dip in perceived mobility during the Obama administration. White Republican voters and racially resentful White people, two groups that overlap, report lower perceived mobility during Obama’s presidency, and a resurgence in perceived mobility after Trump’s election. White Democratic voters and less racially resentful White people display more stable trends across political administrations or experience more secular declines in perceived mobility.

The paper is structured as follows. We begin with a brief discussion of existing literature about race and perceived mobility, developing our predictions for the effects of the Obama presidency on the perceived mobility of different groups of Americans. We then describe our data, variables, and methods. In the results section, we discuss our key findings about racial gaps in perceived mobility and then delve into further details about whether and how political partisanship and racial resentment shape perceptions of mobility among White respondents. We conclude with a brief summary and a discussion of limitations and next steps.

2. Background and Predictions

Despite the central role of social mobility in sociological scholarship, the literature on perceived mobility is still relatively small. Existing social scientific studies on the topic, mostly in social psychology, tend to focus more on people’s perceptions of the openness of a society in general than on people’s assessments of their own past or future trajectories [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The subjective assessment of one’s own life is important, because it is likely to shape a person’s perceptions about other aspects of society, and to affect health and well-being. If people are upwardly mobile but do not believe they are, or conversely, downwardly mobile but unrealistically optimistic, we might expect different consequences than in a world where perceived mobility matches reality, especially if some groups are systematically more accurate in their perceptions than others.

In addition to our focus on people’s perceptions of their own mobility, our study is unique in its focus on racial differences in perceived mobility, and in particular, on racial differences in perceived mobility before, during, and after Barack Obama’s historic presidency. Though it was not the topic of a fully developed study, Cherlin [10], in his 2014 book on the decline of the American working class, notes, in passing, an emerging racial gap in perceived mobility, using some of the same measures that we do from the General Social Survey (GSS). His focus, however, is on secular changes in White and Black perceived mobility, rather than the period-specific patterns we focus on in this paper. Though not focused on perceived mobility per se, we also note a longstanding literature on racial differences in educational aspirations. This might be particularly relevant for the measure in our study that asks about respondents’ views about their children’s prospects for mobility. This literature, going all the way back to the 1966 Equality of Educational Opportunity report [11], but continuing through more recent studies [12], finds that White Americans have consistently lower educational aspirations—but higher educational attainment—than non-White Americans.

The Obama election presents a unique opportunity to study perceived mobility. For non-White, and especially Black, Americans, we might expect that Obama’s election would increase optimism that “people like me” could succeed in American society. Several small-scale qualitative studies have explored this. One study found that young African American men felt that Obama provided a role model, and that Obama’s campaign themes of change and hope inspired them to improve their status positions [13]. However, this study also found that there were few changes in these young men’s actual career aspirations, which remained quite constrained. Another study found that Obama’s election resulted in higher personal motivation for success among African Americans, but ultimately no change in their perceptions of their future life chances [14]. According to the participants in this study, while the election of Obama was inspiring, it did not necessarily remove the barriers that structural inequalities pose. Despite the limited or cautious optimism among respondents in these small-scale studies, we predict that:

Hypothesis 1.

There will be a positive effect of Obama’s presidency on the perceived mobility of non-White, and especially Black, Americans.

For White Americans, we might also expect an Obama effect, but in a different direction, and for different reasons. Group threat theory [15,16] is generally tested using indicators of minority population size [17,18,19]. However, recent research has shown that Obama’s election represents a “power threat” to White respondents, which has an effect on racial bias that is similar to the “majority threat” effect of changes in minority population size [20]. The outcome of interest in most existing studies of group threat is either racial attitudes or attitudes about racialized policies, like those related to crime or affirmative action. However, it stands to reason that racial status threats would also change the way in which White respondents perceive their own status positions, and perhaps particularly their perceptions about their overall trajectories of mobility. Thus, it may be the case that the Obama presidency represented a threat to White respondents’ status position, and therefore had negative effects on their own perceived opportunities for mobility. We might expect this trend to be most pronounced among White respondents who articulate racially resentful views.

In addition to explanations that focus on racial group status, political partisanship is also important to consider in understanding racial differences in perceived mobility. People tend to have more positive assessments of their economic circumstances when the party they support is in power [21,22,23]. Furthermore, non-White Americans are far more likely than White Americans to vote Democratic in recent decades. We might therefore expect substantial variation in perceived mobility among White respondents, depending on whether they supported Obama politically. In other words, we might expect White Democrats to display patterns over the course of presidential administrations that look more like those of their non-White counterparts. We therefore predict that:

Hypothesis 2a.

There will be a negative effect of Obama’s presidency on the perceived mobility of White Americans overall.

Hypothesis 2b.

White respondents who supported Obama politically will experience less steep declines in perceived mobility than other White respondents.

Hypothesis 2c.

Racially resentful White respondents will experience steeper declines in mobility during Obama’s presidency.

In summary, we hypothesize a different “Obama effect” on perceived mobility for White respondents and non-White respondents, after taking into account changes in objective socioeconomic circumstances. We also hypothesize a divergence within the White population based on political orientation and racial resentment. Our analysis is designed to evaluate these predictions.

3. Materials and Methods

The analysis draws on GSS data from 1994 to 2018. We use 1994 as a starting point, because this is the first year in which the GSS includes questions about perceived mobility, which have subsequently been asked in each survey wave, every two years. One-third to two-thirds of all respondents, depending on survey wave, are randomly chosen for the GSS module that includes the perceived mobility questions. A later part of our analysis explores the perceived mobility of White respondents in greater depth, focusing in on how racial resentment and the party for which respondents cast their most recent presidential vote shape perceived mobility. Questions used to construct the measure of racial resentment are asked of a random sample of around one-third to two-thirds of respondents, depending on wave, that only partially overlaps with the sample that is asked the perceived mobility items. Around one quarter of all respondents get the module that contains perceived mobility items and the module that contains racial resentment items. Furthermore, only around 60% of respondents report having voted in the last presidential election. Thus, the sample size for the analysis that includes the racial resentment and voting items is considerably smaller, which precludes a detailed analysis of non-White groups.

The focal variables relate to respondents’ perceptions of their past mobility and of their and their children’s prospects for future mobility. The past mobility item, parsol, asks “Compared to your parents when they were the age you are now, do you think your own standard of living now is much better, somewhat better, about the same, somewhat worse, or much worse than theirs was?” (5-point scale). Two items (also on 5-point scales) tap people’s assessments of future mobility prospects: goodlife, which asks “The way things are in America, people like me and my family have a good chance of improving our standard of living–do you agree or disagree?” and kidssol, which asks “When your children are at the age you are now, do you think their standard of living will be much better, somewhat better, about the same, somewhat worse, or much worse than yours is now?” Note that respondents without children are still asked the kidssol question, and a majority (around two-thirds) of them provide an answer, presumably based on hypothetical or future children. Overall, around 10% of respondents who were asked the kidssol question do not give a valid answer, whereas the figure is much smaller for parsol and goodlife. We reverse coded all three dependent variables so that higher values indicate better perceptions of past mobility or more optimistic assessments of future mobility prospects. We also rescaled all three items for simplicity, so that the minimum value is 0 and the maximum value is 1.

Our analysis of trends uses a period variable referencing presidential administration: Clinton from 1994–2000, (George W.) Bush from 2002–2008, Obama from 2010–2016, and Trump in 2018. Note that during the 1994–2018 period, GSS data were nearly always collected prior to November elections. The exception was 2004, when around one-fifth of interviews were conducted in November and December. In all cases, election year data were collected prior to the commencement of a new presidential administration.

We create an indicator of the respondent’s race/ethnicity from the GSS variables race and ethnic, with the categories White, Black, and Latinx. The 4.7% of respondents who do not fall into one of these three categories, including Asians, Native Americans, and most multiracial respondents, are excluded from the analysis, because given small sample sizes, these groups cannot be meaningfully analyzed. White and Black respondents are those who indicate that they belong to one of those racial groups and do not report Hispanic origins. Latinx respondents are those who indicate Hispanic origins on the ethnic variable. They may be of any race, including multiracial. Unlike the variable hispanic indicating Hispanic origins, which is only available in the GSS from 2000 onwards, the variable ethnic is available for all survey years in the analysis. Note that we often use the term “race” in the rest of the paper to refer to this variable, even though it combines information about race and Hispanic ethnicity.

We control for a respondent’s own and parental education and occupational status, using years of education and socioeconomic index (SEI) scores. “Own” education is, in practice, defined as the mean of own and spouse’s years of education and parental education is defined as the mean of father’s and mother’s years of education. We use the same approach, with SEI scores, to construct the occupational status measures. The GSS unfortunately only contains a subjective measure of income in a respondent’s family of origin, called incom16, which indicates whether a respondent believes the family was below, around, or above the average income at that time. Because the measure is subjective and is likely to conceptually overlap with at least one of our outcome measures (parsol), and because incom16 is mostly not available in the 1990s GSS waves, we chose not to use it in our main analysis. However, findings from the more recent part of the period are similar if we include it. Some, but not all, of the variation in income in a respondent’s family of origin will be captured with the educational and occupational measures. We could, and did, control for current family income. We transformed the GSS income variable coninc, dividing it first by 1000 and then taking the square root of that figure. This results in a more normally distributed variable than either the original coninc variable or than a log transformation of coninc. The variable coninc was constructed by the National Opinion Research Center from year-specific categorical income measures, and was adjusted for inflation to constant 2000 dollars. To further control for objective economic circumstances, we include an indicator of whether one’s family is currently experiencing unemployment (own or spouse’s) and a measure of the current unemployment rate, specific to the respondent’s race/ethnicity and gender. The group unemployment measure is intended to tap a respondent’s perceptions about the risk of unemployment. Group-specific unemployment rates are annual averages reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and are based on Current Population Survey data rather than the GSS.

In addition to these socioeconomic controls, we also controlled for basic demographic and religious characteristics that may influence a respondent’s perceptions of mobility. We used birth year to construct 7 birth cohorts (born before 1930, 1930–45, 1946–55, 1956–65, 1966–75, 1976–85, and after 1985), and we controlled for gender. In a respondent’s family of origin, we measured family structure with a dichotomous indicator of whether a respondent was not living with both parents at age 16, and a categorical variable indicating number of siblings (0, 1–2, or 3+). In a respondent’s current family, we control for marital status (married, widowed, divorced or separated, or never married) and number of children (0, 1–3, or 4+). We included controls for both religious affiliation and religious attendance. Protestants, Catholics, and those belonging to “other” religions are distinguished from the non-affiliated, and for parsimony, we treat the attendance item as continuous although it is actually ordinal, ranging in 9 steps from those who never attend services to those who attend more than once per week. Finally, we include an indicator of whether a respondent is foreign-born. Not surprisingly, this variable is highly associated with race and ethnicity, and including it allows us to disentangle racial differences in responses from differences between foreign- and native-born respondents.

Political partisanship is highly likely to shape the way in which respondents perceive their past mobility and future mobility prospects under different presidential administrations. The GSS contains variables that ask whether respondents voted in specific presidential elections and which candidate they chose. Based on these variables, we construct a variable that indicates whether a respondent supported the Democratic or Republican candidate in the most recent presidential election. Non-voters and third-party voters are excluded from this part of our analysis.

Existing social scientific work has documented the increasing role in politics, not only of race itself, but also of racial attitudes within racial groups. We use a measure of racial resentment to further investigate the trends in perceived mobility that we observe among White respondents. Given sample size constraints, the role of racial attitudes among non-White respondents is beyond the scope of this analysis. The racial resentment measure is constructed with four GSS items, following Kinder and Kam [24] and Tesler and Sears [25]. The first of these is the item wrkwayup, which asks about agreement (on a 5-point scale, higher values = higher racial resentment), with the following statement: “Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without special favors.” The second and third items, racdif1 and racdif4, ask about simple agreement or disagreement with the following: “On the average African-Americans/blacks have worse jobs, income, and housing than White people. Do you think these differences are mainly due to discrimination?” (Disagreement = higher racial resentment) and whether the differences are “Because most African-Americans/blacks just don’t have the motivation or will power to pull themselves up out of poverty?” (Agreement = higher racial resentment). The final item in the racial resentment scale is based on the difference in responses to two survey questions, workblks and workwhts. Both of these items are prefaced with “Now I have some questions about different groups in our society. I’m going to show you a seven-point scale on which the characteristics of people in a group can be rated...The second set of characteristics asks if people in the group tend to be hard-working or if they tend to be lazy. Where would you rate [whites/blacks] in general on this scale?” (7-point scale from hard-working = 1 to lazy = 7). We construct a 3-point indicator of whether respondents score Black people lower than, equal to, or higher than White people on laziness (Higher = more racial resentment). The four racial resentment items are then rescaled and averaged, so that each contributes a maximum of 0.25 points to a racial resentment scale, ranging from 0 (low racial resentment) to 1 (high racial resentment).

Before conducting our analyses, we use listwise deletion based on all variables in the given set of models. Note that there are very few missing values for parsol and goodlife and somewhat more for kidssol. This is because, as we noted above, around one-third of childless respondents (around 10% of all respondents) do not give a valid answer to the kidssol question. For the sake of comparison, we only include cases with valid values on all three outcomes. The final sample size of respondents who have valid values on all variables used in the analysis of racial differences in perceived mobility is 12,814. The sample size for the more detailed analysis of White respondents that include the political partisanship and racial resentment measures is 2636.

We use ordinary least squares regression models to predict perceived mobility outcomes. All models use the sampling weights contained in the GSS variable wtssall to adjust for sampling design. As noted above, we include an unemployment variable that is specific to demographic group (race/ethnicity and gender) and year. Because of this, standard errors are adjusted for clustering on group-year.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

We begin with a first glimpse at racial differences in perceived mobility. At the top of Table 1, we see that, for the entire sample, pooled across all survey years, White respondents have lower average levels of perceived mobility according to all three measures. The White/non-White gap is largest for the measure of perceptions about children’s future mobility prospects.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

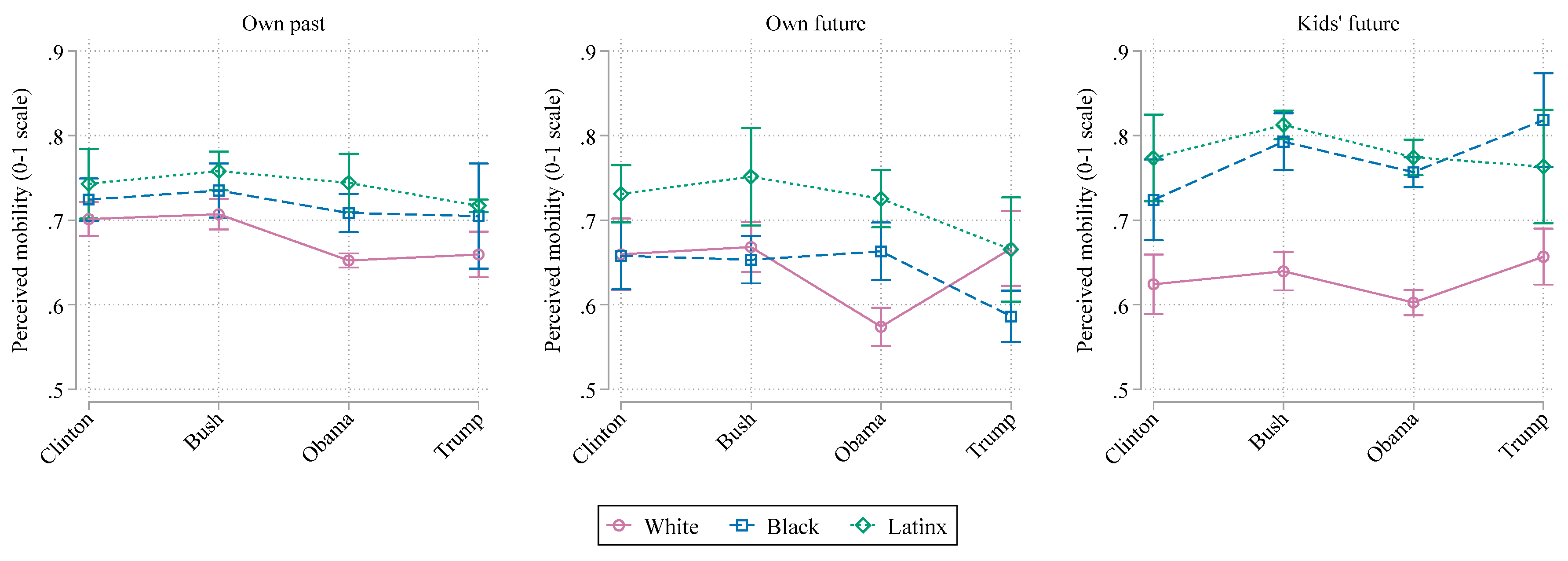

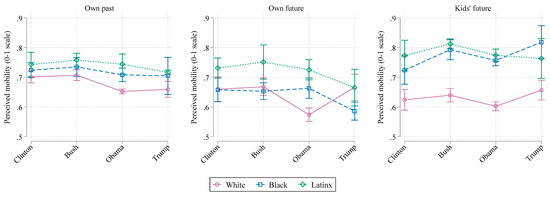

Figure 1 shows that racial differences in the three different perceived mobility measures vary by presidential administration. During the Clinton and Bush administrations, Black and White respondents are indistinguishable in terms of perceptions of their own perceived past mobility and own future mobility prospects. During these same administrations, Latinx respondents have somewhat higher perceived mobility according to these two measures than either White or Black respondents, but the differences across groups are largely insignificant.

Figure 1.

Perceived mobility, by race and presidential administration (unadjusted). Confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

During the Obama administration, Black and Latinx respondents maintain stable levels of perceived mobility according to these two measures, with Black respondents continuing to post somewhat lower levels of these two measures than Latinx respondents. However, White respondents diverge from both other racial groups because of a substantial drop in their perceived mobility.

For the measure about one’s children’s future prospects, the two non-White groups are indistinguishable from one another across periods. They have far more positive perceptions than White respondents throughout the entire period under study. Here, too, we observe a decline in perceived mobility among White respondents between the Bush and Obama administrations, though it is just under the threshold for statistical significance.

The 2018 GSS, the only survey wave fielded during the Trump administration, hints that White mobility perceptions have increased again for this most recent time point, narrowing the gap with non-White groups. By 2018, White respondents’ perceptions of their own and their children’s prospects for future mobility are again at least on par with their levels before the Obama administration. Non-White groups do not post significant increases, and gaps between White and minority groups narrow again, especially for perceptions about one’s own future mobility prospects. Perceptions of past mobility, on the other hand, remain at a lower level among White respondents than they were prior to the Obama presidency, and racial gaps in this outcome therefore remain relatively stable in size during the Trump administration.

The most obvious explanation for differences in perceptions of mobility, whether over time, by race, or by other individual attributes, is that experiences of objective mobility differ. Contemporary social research on mobility distinguishes between absolute mobility (the inter- or intra-generational distance a person travels or the average distance the members of a certain group travel) and relative mobility (the chances that members of one group attain a certain end position relative to members of another group). The openness or social fluidity of a society is generally measured in terms of relative mobility: how different the prospects are (i.e., the relative mobility) of individuals from more and less disadvantaged backgrounds. Unlike many existing studies about the perceptions of mobility, our indicators of perceived mobility ask respondents to consider absolute mobility. This is good in the sense that individuals probably have reasonably accurate information about the difference between their own and their parents’ positions, and may be less likely to know how that compares to the experiences of other groups.

For understanding racial differences in mobility perceptions, it is important (a) that there are racial differences in the distribution of social origins, and (b) that given the same social origins, there are racial differences in mobility. In particular, note that a group can experience more absolute upward mobility than another, while still facing disadvantages relative to that other group in attaining the highest positions. This is because downward absolute mobility is impossible when one starts at the bottom. The reverse is also true in terms of upward absolute mobility for individuals starting at the top. In shaping people’s mobility perceptions, racial differences in social origins may in some instances work against the effects of racial differences in mobility, given the same origins. For instance, as we see in Table 1, Black and Latinx respondents begin, on average, further down in the hierarchy of social origins. However, consistent with recent studies [26], GSS data show lower mobility for Black and Latinx respondents, compared to White respondents, once differences in social origins are accounted for. These two sets of racial differences—in origins and in mobility chances given the same origins—result in the racial differences in absolute intergenerational mobility in education and occupational status observed in Table 1.

In terms of education, Black, and especially Latinx, respondents have higher average levels of absolute intergenerational mobility, but also more variability in mobility, than White respondents. This is in part because disadvantaged educational origins give them further to climb. In terms of occupational status, the picture is more complicated. Latinx respondents post the lowest rates of mobility, despite the most disadvantaged occupational origins. As with educational mobility, Black respondents do have higher absolute occupational mobility than White respondents, due in part to the lower origins of Black respondents. It is crucial to adjust for all of these objective mobility cues, in order to rule out the possibility that observed differences in perceived mobility are simply a function of different objective experiences of mobility. Racial differences in unemployment and family income follow similar patterns to the other socioeconomic variables, with lower average unemployment and higher average income among White respondents.

In addition to differences in objective socioeconomic characteristics, which may help to explain some of the racial differences in perceived mobility that we observed above, Table 1 also documents differences in demographic characteristics. For instance, Black and Latinx respondents are more likely than White respondents to have lived in a non-nuclear family at age 16. They are also more likely than White respondents to be from large families with three or more siblings. In adulthood, White respondents are more likely to be currently married than Latinx and especially Black respondents. Though the majority of respondents in every racial group have 1–3 children, Black and Latinx respondents are more likely than White respondents to have large families of four or more children. As with the objective mobility controls, these demographic factors may shape how respondents experience and perceive their socioeconomic circumstances.

Racial differences related to religion and foreign-born status follow expected patterns. Black respondents are more likely to be Protestant and Latinx respondents are more likely to be Catholic, compared to White respondents. Black respondents report the highest levels of religious attendance, with a relatively small difference across the other two groups. Latinx respondents are, as we would expect, far more likely to be foreign-born than White and Black respondents. If religious beliefs and practices and migration experiences affect respondents’ perceptions of mobility, then again, racial differences in these factors are important to control.

In the second stage of our analysis below, we explore explanations for trends in White respondents’ perceptions of mobility in further depth. These models include variables indicating a respondent’s last presidential vote and the indicator of racial resentment and limit the sample to White respondents who have valid values on both of these variables. Consistent with existing research, White respondents in this sample lean Republican in their presidential voting overall. Their average racial resentment score is 0.64, slightly more than halfway between the minimum and maximum values on this measure.

4.2. Multivariate Models

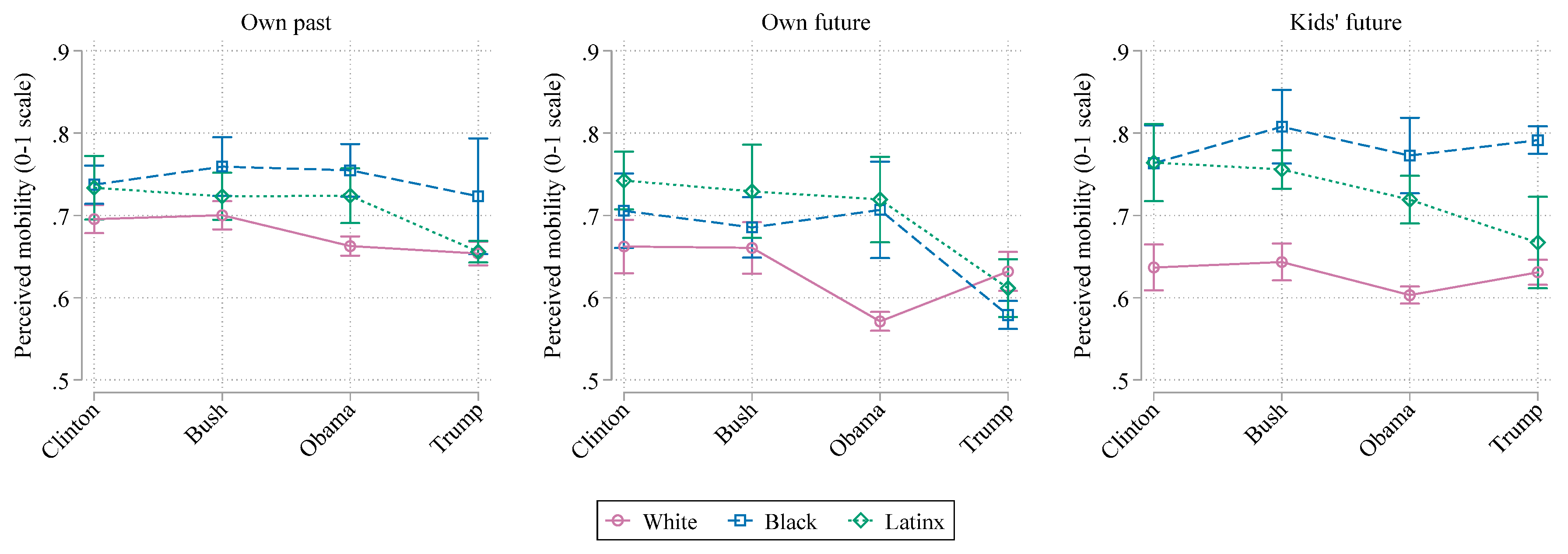

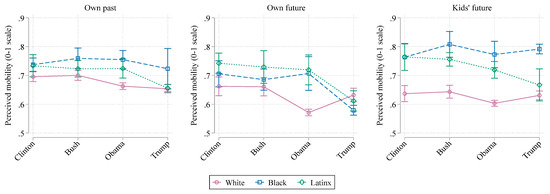

We turn now to results about racial differences in perceived mobility that account for potentially confounding variables. These models, presented in Table 2, focus on the effects of presidential administration, race, and the interaction between the two, while controlling for the socioeconomic, demographic, and religious variables that we highlighted above. Because of the complexity of interpreting the interaction terms between race and time period, we graphically present these results in the form of predictive margins, displayed in Figure 2. Predictive margins average the predicted level of perceived mobility across everyone in the sample, fixing race and time period to the given categories in turn.

Table 2.

Models predicting perceived mobility.

Figure 2.

Perceived mobility, by presidential administration and race (adjusted for socioeconomic and demographic controls). Confidence intervals are at the 95% level. Predictive margins are based on models in Table 2.

We begin by noting that, as we saw earlier in the unadjusted figures, White Americans are generally somewhat less positive about their own past mobility and their own future mobility than non-White Americans, but during most presidential administrations, these racial differences are small and statistically insignificant. White Americans are consistently and significantly less positive than non-White respondents about their children’s future mobility prospects.

Turning to trends over consecutive administrations and how they differ by race, we see, first, that there are no significant changes between the Clinton and Bush administrations for any racial group. It is therefore clearly not the case that the perceived mobility of Americans always or generally fluctuates over the course of presidential administrations. There continue to be no significant changes in non-White respondents’ mobility perceptions between the Bush and Obama administrations. However, between the Bush and Obama administration, according to all three measures, White respondents’ mobility perceptions decline significantly. As noted above, the models on which these figures are based control for basic economic factors, including unemployment at both the level of the respondent’s household and demographic group. So, after accounting for the economic changes that were certainly underway over the course of these two presidential administrations, White and non-White respondents have quite different responses in terms of perceptions of their and their children’s mobility. In particular, there is a negative effect of the Obama presidency on White respondents’ perceptions of mobility, while there is relative stability in the perceived mobility of the two non-White groups.

Between the Obama and Trump administrations, Latinx respondents perceive a decline in mobility according to all three measures, though this dip is not significant for perceptions about children’s future mobility prospects. There is also a significant decline in Black respondents’ perceptions of their own future mobility prospects. As in the unadjusted averages in Figure 1, we see here that White respondents experience an uptick in their perceptions of their own and their children’s future mobility prospects between the Obama and Trump administrations, returning these outcomes to levels that are similar to those observed before the Obama administration. However, there is no similar uptick for the perceived past mobility outcome.

To return to our hypotheses from above and to sum up this set of findings, we find little evidence in support of Hypothesis 1, which predicted a positive effect of Obama’s presidency on the perceived mobility of non-White respondents, at least in an absolute sense. Perceived mobility among non-White respondents is largely stable across the first three presidential administrations in the study (Clinton, Bush, and Obama). It is possible that we would have observed a dip in non-White perceived mobility during the Great Recession had Obama not been elected, though we note that objective economic factors such as unemployment are controlled in our statistical models. We do see evidence for Hypothesis 2a, which predicted a negative Obama effect on the perceived mobility of White respondents.

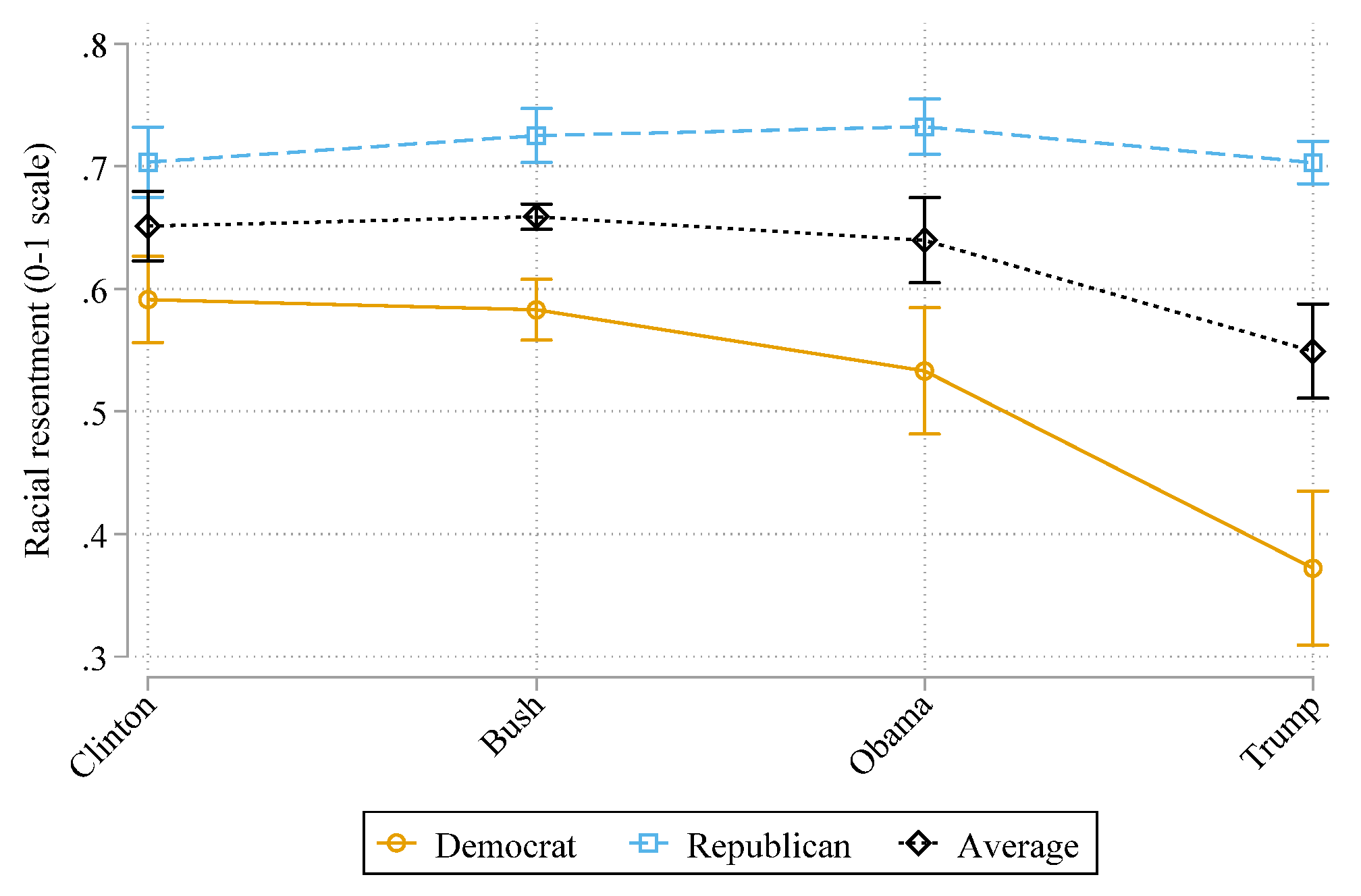

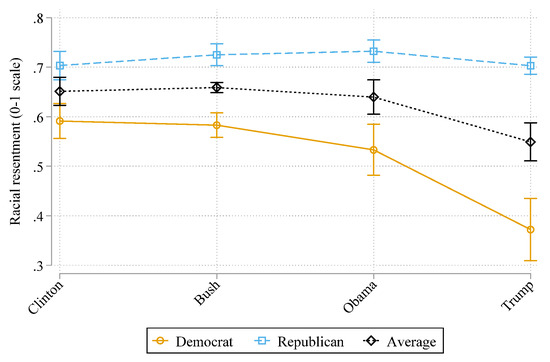

We now turn to a set of models that allows us to examine the perceived mobility of White respondents in greater detail. In particular, we focus on how political partisanship and racial resentment shape the overall trends we have already observed. It is important to note, before discussing these models, that among White respondents, party choice and racial resentment are strongly associated with each other, which can be observed in Figure 3. Average levels of expressed racial resentment among White respondents have declined in more recent years, but interestingly, this decline is concentrated entirely among Democratic voters. Among Republican voters, the levels of racial resentment are stable across the entire period of study and we see no such decline. The result is that the difference in average racial resentment between Republican and Democratic voters has substantially widened, with a particularly large gap for the Trump administration data point. In the models we present, we examine the independent effects of last presidential vote and racial resentment, but we should keep in mind that the two factors are associated in this way.

Figure 3.

Racial resentment among White respondents, by presidential administration and last presidential vote. Confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

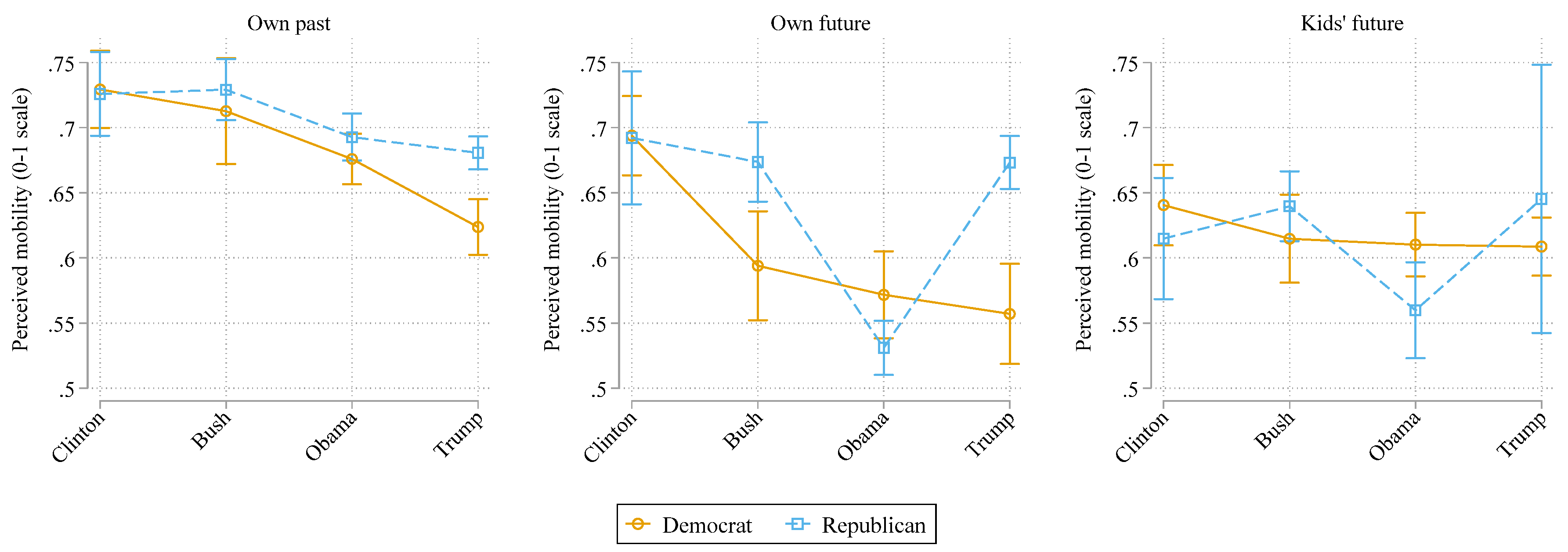

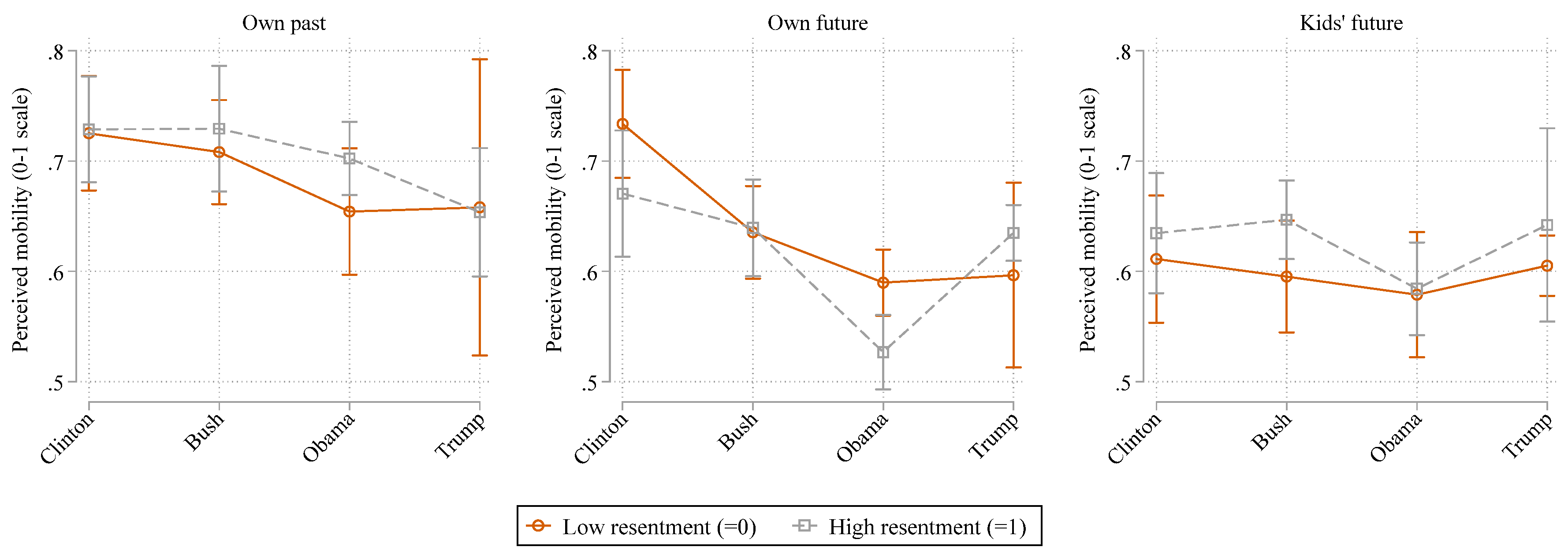

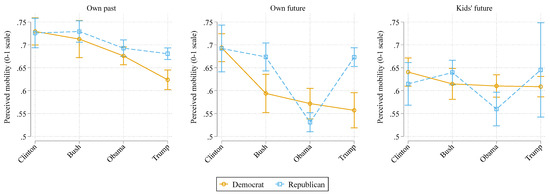

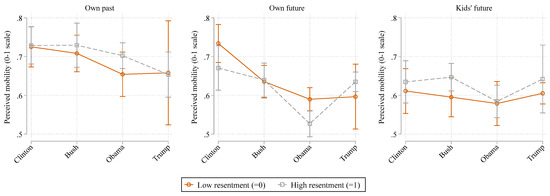

Our analysis includes indicators of a respondent’s last presidential vote, racial resentment, and interactions between each of these two factors and presidential administration. We include the same control variables as in the models for all racial groups above. The full models are presented in Table 3. Again, in order to facilitate the interpretation of the relatively complex interaction terms, we provide predictive margins in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Table 3.

Models predicting perceived mobility among White respondents only.

Figure 4.

Perceived mobility among White respondents, by presidential administration and most recent presidential vote. Confidence intervals are at the 95% level. Predictive margins are based on models in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Perceived mobility among White respondents, by presidential administration and racial resentment. Confidence intervals are at the 95% level. Predictive margins are based on models in Table 3.

At the beginning of the period under study, during the Clinton administration, there are no partisan differences in perceived mobility according to any of the three measures. This pattern continues into the Bush administration, with one exception: We observe a drop in White Democrats’ perceptions of their own future mobility prospects between the Clinton and Bush administrations. This decline is partisan in nature and was not visible in the aggregate figures for White respondents. However, this greater pessimism among White Democrats about their own future prospects did not rebound during the Obama administration, as a strict story of partisanship might predict, and if anything, continued to decline during the Trump presidency, though this continued decline is not statistically significant.

The decline in White respondents’ perceived mobility between the Bush and Obama administrations that we observed above in Figure 2 is entirely partisan. For the measures of one’s own and one’s children’s future mobility prospects, there is a significant drop between these two administrations for Republican voters, but no significant change for Democratic voters. Similarly, there is a rebound to pre-Obama levels in these two measures (albeit not significant for perceptions of children’s mobility prospects) between the Obama and Trump administrations among Republican voters, but stability among Democratic voters. So, White Democrats’ expectations about their own and their children’s future mobility prospects are largely stable over the period of study, aside from the dip between the Clinton and Bush administrations in perceptions of their own future mobility prospects. On the other hand, White Republicans’ perceptions of their own and their children’s future mobility prospects fall during the Obama administration and rise afterwards. It should be noted that this is a pattern that was not observed during the earlier Democratic administration of Bill Clinton, when White Republican perceived mobility was relatively high.

Perceived past mobility appears somewhat less partisan through the Obama administration, and instead seems to follow a gradual decline among both those White respondents who vote Democrat and those who vote Republican. However, White respondents’ assessments of their past mobility diverge by partisanship in the Trump administration, with White Democratic voters experiencing a continued and even steeper decline, while White Republican voters experience a leveling off.

In Figure 5, we see predictive margins for highly racially resentful White respondents versus less racially resentful White respondents. The somewhat more extreme trends we observe for racially resentful White respondents for the two future-oriented outcomes are similar in direction to those we observe among Republican voters. For instance, highly resentful White respondents experience a steeper drop between the Bush and Obama administrations and a steeper increase between the Obama and Trump administrations. As with the patterns for political partisanship, the pattern here is most pronounced for perceptions of one’s own future mobility prospects, and less pronounced for perceptions of one’s children’s future mobility prospects. The fact that political partisanship and racial resentment are not independent, as we observed earlier, means that the differences we observe by racial resentment make the patterns by partisanship that we saw in Figure 4 even more extreme for “typical” Democratic and Republican voters than under the assumption that Democratic and Republican voters have the same level of racial resentment.

In summary, we find evidence that changes in White respondents’ perceived mobility over consecutive presidential administrations—a decline in perceived mobility between the Bush and Obama administrations and a subsequent resurgence in perceived mobility between the Obama and Trump administrations—are driven by White Republican voters and racially resentful White people, two groups that substantially overlap. The levels of perceived mobility among White Democratic voters and less racially resentful White people are generally stable or suggest a more secular decline over time. This evidence is consistent with Hypotheses 2b and 2c above, which predicted that a negative Obama effect would be concentrated among White Republican voters and racially resentful White people.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we have examined trends in levels of and racial gaps in perceived mobility, that is, people’s perceptions of their own past mobility and their and their children’s prospects for future mobility. Adjusted for controls for respondents’ socioeconomic, demographic, and religious characteristics, we document a racial gap in optimism about mobility that grows, and in some cases emerges for the first time, with Obama’s presidency, and then shrinks again afterward. We qualify this general finding in two ways. First, we note that this pattern is most pronounced in the two of three outcomes we examine that focus on the future, one’s own and one’s children’s future prospects for mobility. It is probably the case that assessments of the future are simply more subjective than assessments of the past. There is an objective reality against which to compare one’s past trajectory, whereas one’s assessment of the future is just a prediction. To be sure, even taking objective mobility trajectories into account, we still see significant differences in perceptions of past mobility across racial groups and according to other predictors. However, optimism about the future is probably more likely to be swayed by one’s views of the current political climate. The second qualification to the finding of a negative Obama effect on the perceived mobility of White people is that the effect is concentrated among specific groups of White respondents. The perceived mobility of White Democratic voters and less racially resentful White people is fairly stable, and it is generally only among White Republican voters and more racially resentful White people that we see mobility perceptions that decline during the Obama administration and rise again after it.

We emphasize the historical specificity of our finding of a negative Obama effect on perceived mobility among White Republican voters. For instance, it is not the case that we observe responses to the perceived mobility items that are generally dependent on the alignment of one’s own vote and a President’s political party. White voters of both parties had stable perceived mobility overall between the Clinton and Bush administrations. Indeed, White Democratic voters display relatively stable perceptions of mobility throughout the entire period under study, or in some cases, display a more secular decline in their perceptions of mobility. The pattern of partisan trends in mobility perceptions was new under Obama’s presidency, and there is some indication that divergences by partisanship continue into the Trump presidency.

With a single data point since Trump’s election, our ability to draw conclusions about the most recent period is limited, but there is an intriguing uptick in White Republican voters’ and racially resentful White people’s perceived prospects for their own and their children’s future mobility after Trump’s election, consistent with the racially charged rhetoric of his campaign and presidency, promising to “make America great again.” It will obviously be important to continue to track these patterns as we have access to additional data collected during the Trump administration. The next GSS wave is in the field in 2020, and the events of 2020 certainly threaten Americans’ economic prospects in an even more significant way than during the Great Recession. Future research on perceived mobility should incorporate the implications of these recent developments.

Sociologists have long been interested in objective social class mobility, and in the cultural and behavioral correlates of class position and class mobility. We implore other scholars to more seriously consider the important role of people’s actual perceptions of their own mobility. Ultimately, if people have a false (or at least highly subjective) consciousness, not only about their class positions, but also about their class mobility, and if divergences between objective and subjective mobility vary systematically by critical individual characteristics like race, racial attitudes, and partisanship, our focus on objective mobility alone may severely limit our understanding of political and social change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and A.C.; Investigation, C.K. and A.C.; Methodology, C.K.; Visualization, C.K.; Writing—original draft, C.K. and A.C.; Writing—review & editing, C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We presented results from this paper at the Summer 2019 meetings of the International Sociological Association’s Research Committee on Social Stratification and Mobility (RC28) at Princeton University, and are grateful for the helpful comments we received there. We also thank Carrie LeVan for her useful suggestions about the project. All remaining errors are our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stephens-Davidowitz, S. The cost of racial animus on a black candidate: Evidence using Google search data. J. Public Econ. 2014, 118, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesler, M. Post-Racial or Most-Racial: Race and Politics in the Obama Era; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; Stantcheva, S.; Teso, E. Intergenerational mobility and preferences for redistribution. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 521–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.R.; Swan, L.K.; Heesacker, M. Perceptions of U.S. Social Mobility Are Divided (and Distorted) Along Ideological Lines. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidai, S.; Gilovich, T. Building a more mobile America—One income quintile at a time. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidai, S.; Gilovich, T. How should we think about Americans’ beliefs about economic mobility? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2018, 13, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Day, M.V.; Fiske, S.T. Movin’ on Up? How Perceptions of Social Mobility Affect Our Willingness to Defend the System. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, M.W.; Tan, J.J.X. Americans overestimate social class mobility. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 58, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, L.K.; Chambers, J.R.; Heesacker, M.; Nero, S.S. How should we measure Americans’ perceptions of socio-economic mobility? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2017, 12, 507. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin, A.J. Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working—Class Family in America; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Equality of Educational Opportunity: Summary Report; U.S. Office of Education: Washington, WA, USA, 1966.

- Schneider, B.; Saw, G. Racial and Ethnic Gaps in Postsecondary Aspirations and Enrollment. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conchas, G.Q.; Lin, A.R.; Oseguera, L.; Drake, S.J. Superstar or scholar? African American male youths’ perceptions of opportunity in a time of change. Urban Educ. 2015, 50, 660–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.K. The Obama Effect and Its Relationship to the Perceptions of Blacks on Education and Social Mobility; Loyola University Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock, H.M. Toward a Theory of Minority—Group Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1958, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, M. Do numbers really count? Group threat theory revisited. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2007, 33, 1253–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, L. Group threat and regional change in attitudes toward African-Americans. Am. J. Sociol. 1996, 102, 816–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, E.; Scheepers, P. The relationship between outgroup size and anti-outgroup attitudes: A theoretical synthesis and empirical test of group threat—And intergroup contact theory. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A.L.; Cheadle, J.E. The “Obama Effect”? Priming Contemporary Racial Milestones Increases Implicit Racial Bias among Whites. Soc. Cogn. 2016, 34, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boef, S.; Kellstedt, P.M. The political (and economic) origins of consumer confidence. Am. J. Political Sci. 2004, 48, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, P.K.; Kellstedt, P.M.; McAvoy, G.E. The consequences of partisanship in economic perceptions. Public Opin. Q. 2012, 76, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A.S.; Huber, G.A. Partisanship, political control, and economic assessments. Am. J. Political Sci. 2010, 54, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinder, D.R.; Kam, C.D. Us against Them: Ethnocentric Foundations of American Opinion; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tesler, M.; Sears, D.O. President Obama and the Growing Polarization of Partisan Attachments by Racial Attitudes and Race; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R.; Hendren, N.; Jones, M.R.; Porter, S.R. Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).