Abstract

Direct support professionals (DSPs) play a vital role in supporting and sustaining the life qualities of individuals with developmental disabilities (DDs). The occupation is often challenging due to a multitude of workplace deficiencies and certain challenging behaviors associated with DDs. The demanding nature of job duties can cause compromised job satisfaction in DSPs, which in turn potentially undermines the quality of care they provide to individuals with DDs. The literature is limited addressing how psychosocial factors relate to job satisfaction specifically in DSPs. The present study examined self-efficacy as a psychosocial correlate for job satisfaction in DSPs and how one’s disposition for perspective-taking functioned as a moderator for the relationship between self-efficacy and job satisfaction. A sample of 133 DSPs responded to self-report measures for self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and perspective-taking. The results of multivariate regression indicated a positive relation between self-efficacy and intrinsic job satisfaction in DSPs, and the relation strengthened as the level of perspective-taking increased, suggesting a moderating role of perspective-taking in DSPs. The findings provide insights for targeting psychosocial correlates as an important element in training programs aimed at improving intrinsic satisfaction in DSPs.

1. Introduction

Direct support professionals (DSPs) are professionals who provide support for the safety and daily functioning of individuals with disabilities [1]. Quality and reliable support from DSPs also enables possibilities for families of individuals with disabilities to carry out everyday tasks and gain respite from the demanding caregiving responsibilities. For individuals with severe developmental disabilities (DDs), particularly those who have the need to reside in long-term care community facilities due to significant impairments, residential DSPs play a vital role in sustaining and improving life qualities for individuals with DDs and their families.

Providing quality services for individuals with DDs can often bring about positive and rewarding experiences to DSPs, much like those following prosocial actions and often involving a sense of fulfillment and empowerment [2]. As well as this, the vast amount of time that DSPs spend supporting those individuals with DDs gives DSPs a unique lens of perspective into the lives of such individuals [3] and makes DSPs feel connected to those with DDs and even more intrinsically motivated to provide support and services. However, providing quality care for individuals with DDs is often trying and vexing due to an array of challenging behaviors exhibited by the individuals with DDs and numerous undesirable workplace conditions for DSPs, including low wages, lack of paid time off, lack of sufficient professional training, and poor access to health insurance and other benefits [1,3]. All these challenging factors have direct relevance to workers’ reports of stress, poor health, burnout, and intention to resign [3,4], as well as a range of workforce issues, including staff’s frequent absenteeism, high turnover rate, insufficient number of workers, insufficient training and professional development, high rates of physical injury, isolation from other workers and supervisors, etc. [1,3,4]. The average wage for DSPs who work full time is below the federal poverty level for a family of four [3,5]. Some organizations provide health insurance and paid time off to full time DSPs, but not all; part time DSPs typically do not get any benefits [3]. It is common for DSPs to work one (or even two) jobs in order to pay bills and make ends meet. The perpetually low wages and limited benefits that accompany the DSP profession ultimately makes it difficult for organizations to recruit and retain DSPs. With at least five million Americans with DDs [6,7] who need well-trained and skilled DSPs to provide quality services, there has been a crisis faced by the long-term services and support workforce that has had direct impacts on individuals with DDs, their families, their communities, and even the U.S. economy [3].

In addition to pushing for governmental policies and efforts at the local, state, or federal level to find solutions for the DSP workforce crisis, it is also important to identify and understand the psychosocial dispositional correlates that empower a direct support worker’s professional identities, general competence, and job satisfaction. Focusing on strengthening and fostering the psychosocial correlates that potentially strengthen DSPs’ sense of fulfillment and gratification would enthuse DSPs’ connections to the individuals they serve on a day-to-day basis and further motivate DSPs to actively engage in the services they provide. In contrast, DSPs who are less satisfied with their occupation would feel less motivated or energized and in turn may provide lower quality care for individuals with developmental disabilities. Thus, strengthening individual dispositional factors may prove to be beneficial to the worker’s job satisfaction and well-being, which, in turn, should yield more efficient, high-quality, and long-term care for individuals with DDs [8,9,10].

The existing literature on the psychosocial correlates for job satisfaction in DSPs specifically is limited; however, studies conducted on healthcare professionals, specifically healthcare professionals and staff of homes for the elderly and individuals with needs, have examined the psychosocial correlates for job satisfaction [11,12,13,14,15,16,17], suggesting the relevance of psychological correlates to job satisfaction in populations that provide long-term care to individuals with needs. The purpose of this study was to examine how these two socio-cognitive correlates—self-efficacy and perspective-taking—jointly related to job satisfaction in DSPs and if there was an interaction effect of the two correlates on job satisfaction. The findings may shed light on training programs aimed at improving direct support workers’ sense of job satisfaction derived from their daily challenging work tasks.

1.1. Job Satisfaction

A general sense of job satisfaction is the contentment that an individual perceives from carrying out a job at the workplace [12,13,14]. A sense of satisfaction at work has been found to be associated with subjective well-being and general life satisfaction [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]; thus, a sense of job satisfaction has ramifications for overall functioning and the quality of service offered by DSPs. Two components comprise a general sense of job satisfaction—namely, intrinsic job satisfaction and extrinsic job satisfaction. Intrinsic job satisfaction involves an individual’s subjective sense of accomplishment and fulfilment with the performed job tasks [11,12,13,14,15]. A multitude of factors affect an individual’s intrinsic job satisfaction, including personal responsibility, self-directedness, the development of skills, and perceived triumph and achievement. Extrinsic job satisfaction is an individual’s perception and feelings about various aspects of their work situation that are external to the job tasks themselves [11,12,13,14,15], including a company’s policies, relations with supervisors, security, benefits, compensation, and hierarchical company models, etc. In the context of the work situations of DSPs, however, the competence in socio-cognitive reasoning (the process that involves reasoning about social situations and interactions) that potentially facilitates direct support workers’ appraisal and perception of their job satisfaction has not been addressed in the literature. However, as mentioned previously, studies have been conducted in other professions such as healthcare and long-term caregiving for the elderly on the associations between work conditions, socio-cognitive reasoning, and job satisfaction [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The findings in other populations, although not able to be applied directly to this study, point to the importance of providing insights for the DSPs on how relevant socio-cognitive processes are involved in their appraisals about themselves in relation to the individuals they serve, their employers, co-workers, work place conditions, and their own personal aptitudes and resources. This information may aid DSPs in accurately framing their perceived sense of job satisfaction despite objectively stressful and demanding job situations.

1.2. Self-Efficacy

The current study examines self-efficacy as a psychosocial correlate for job satisfaction in DSPs due to its feature of inter-subjective reasoning (i.e., reasoning about self and others). Perceived self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their ability to effectively exert control over challenging situations and achieve desired goals, which often results from experiencing task mastery and receiving positive feedback from others for completing task requirements [18,19]. Research has indicated that self-efficacy is a positive correlate of psychological well-being and job performance [17,20,21,22,23]. High levels of self-efficacy suggest a positive sense of self, and high degrees of commitment to responsibilities and are associated with better competence in solving problems and adjusting to one’s environment [18,19,21,22,23]. Individuals with high self-efficacy welcome challenges, are interested in learning, are more resilient to difficulties, and are more likely to achieve the goals they set for themselves [18,19,21,22,23]. Contrarily, low self-efficacy is associated with low self-confidence, negative views of oneself, and the inability to meet goals. Since caring for individuals with DDs and helping them with their daily functioning can often be accompanied with challenges and difficulties, it follows that DSPs with high levels of self-efficacy would be better equipped to deal with their job demands. Therefore, self-efficacy may prove to be a supporting factor for DSPs’ job satisfaction.

1.3. Perspective-Taking

Another psychosocial correlate of interest that also implicates the inter-subjective reasoning process (reasoning about self and others) and thus may be relevant to DSPs’ job satisfaction is perspective-taking. Perspective-taking involves entering into the perspectives of another person and objectively perceiving the person’s experiences [24]. This process of putting oneself in someone else’s shoes—i.e., reasoning about another person’s perspectives and vicariously experiencing another’s circumstances—has been conceptualized as the cognitive component of empathy [24]. Research has indicated that the propensity for perspective-taking is one of the most important personality dispositions that support human service workers and healthcare professionals to overcome the demanding nature of job duties and feel rewarded by serving individuals with needs [25,26,27,28,29]. It follows that DSPs who understand the perspectives of the individuals they are serving are likely to offer help and care that address the individuals’ specific needs and are more likely to report positive affect and higher levels of well-being. They are also more likely to report feeling satisfied with their jobs and experience less burnout.

Although both self-efficacy and perspective-taking involve socio-cognitive reasoning about the self and others and are relevant to job satisfaction, the literature has yet to describe how these two processes relate to job satisfaction in DSPs. Further, if both are related to job satisfaction in DSPs, how self-efficacy and perspective-taking work in concert to relate to job satisfaction may shed light on the potential implications for improving job satisfaction. To our knowledge, there have not been reports on whether the two correlates show interaction effects on job satisfaction in DSPs.

1.4. The Present Study

The purpose of this study was to identify possible psychosocial correlates that supported DSPs in effectively performing their job and therefore achieving job satisfaction. We sought to examine the roles self-efficacy and perspective-taking played in the prediction for job satisfaction in DSPs.

Based on the reviewed literature, we hypothesized that higher scores in self-efficacy would relate to DSPs feeling more gratified about their job in the aspects of intrinsic, extrinsic, and overall sense of satisfaction. Additionally, we predicted that a greater propensity for perspective-taking reported by the DSPs would relate to higher levels of job satisfaction. Due to the limited information on how self-efficacy and perspective-taking jointly relate to job satisfaction in DSPs, the examination for the potential interaction effect in this study was primarily exploratory. Here, we consider the relations of these study variables in light of the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) [30,31]. The COR posits that both the objective and individually perceived circumstances need to be integrated when considering the process of conserving available resources to maximize the goal-directed outcomes. Given the stressful nature of the circumstances and experiences commonly shared by a large number of DSPs, one’s belief in the ability to effectively handle challenging situations (i.e., self-efficacy) and the competency in accurately appraising the self in relation to the objective and common demands (i.e., perspective-taking) can be deemed as valuable resources [32,33]. The theoretical perspective of the COR is relevant for conceptualizing the relations of the two psychosocial correlates and job satisfaction in DSPs, because the two correlates involve cognitive appraisals relative to the group and broad-based common perceptions of the environmental demands generally facing DSPs. In light of this perspective, we hypothesized that the two resources are both vital to successful coping and desirable outcomes within the working environment, and self-efficacy and perspective-taking would interact and mutually enhance the functions of each other to contribute to job satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A sample of 133 DSPs were recruited from a governmental supported services center located in a moderately small-sized town in the southern USA. The center serves approximately 600 individuals with developmental disabilities (DDs) residing in a group home type of setting within the center. The disabilities in the individuals being served include autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, Fragile X Syndrome, Down syndrome, etc., with varying degrees of severity and comorbid medical conditions. The center employs around 500 DSPs who work 12 h-shifts in two-day increments. The DSPs were the people with whom the individuals with DDs had the most contact, although for each individual there was an interdisciplinary team consisting of a psychologist, a psychiatrist, a physician, nurses, assistants to a psychologist, and a caseworker.

The inclusion criteria for DSPs to participate in this study included (1) being employed at the center at the time when the study was being conducted, (2) working at least 3 shifts per week, and (3) having been employed for at least two months at the center. The exclusion criteria included (1) being out of client care, or (2) still being in the staff training process as being newly hired DSPs. When a DSP is “out of client care”, the DSP is being investigated due to complaints filed by an individual with DDs, a family member, or a coworker at the center. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the researchers’ institution as well as the Human Rights Committee at the center. All the participants provided their consent before responding to the survey.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the sample. The ages of the DSPs in this study ranged from 20 to 65, with a mean of 35.03 years old (SD = 11.68). The sample was comprised of 78% females (n = 103) and 22% males (n = 30). On average, the DSPs had been working at the center for nearly 4 years (M = 3.84, SD = 1.35). Of the DSPs that participated in the study, 73% were African American (n = 97); 17% were European American/Caucasian (n = 23); and less than 1% of the participants were Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 1), American Indian (n = 4), or other (n = 7). For approximately 98% of the sample, the highest degree of education they had completed was high school.

Table 1.

Characteristics of direct support professionals in the current study (N = 133).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) Short Form [34] is a 20-item measure assessing an employee’s satisfaction with his or her job. The MSQ Short Form includes three subscales: the intrinsic satisfaction (12 items), the extrinsic satisfaction (6 items), and the general satisfaction (20 items). There is a lead-in question for each of the items: “Ask yourself: How satisfied am I with this aspect of my job?” Each item states one particular aspect of the participant’s job. An exemplar item from the intrinsic subscale is, “The chance to do things for other people”; an exemplar from the extrinsic subscale is, “The chances for advancement on this job”. An exemplar item from the intrinsic subscale is, “being able to keep busy all the time”; an exemplar from the Extrinsic subscale is, “The way my boss handles his/her workers”. Participants rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied), 2 (dissatisfied), 3 (neutral), 4 (satisfied), to 5 (very satisfied). The subscales scores were tallied by summing the item scores within the subscales; the score on general satisfaction was the sum of all the items of the MSQ. According to Weiss et al. [34], the reliability coefficients for the intrinsic satisfaction subscale ranged from 0.84 to 0.92, the extrinsic satisfaction subscale from 0.77 to 0.82, and the general satisfaction subscale from 0.87 to 0.92. For the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92 for the intrinsic satisfaction subscale, 0.89 for the extrinsic satisfaction subscale, and 0.95 for the general satisfaction subscale.

2.2.2. The General Self-Efficacy Scale

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) [35] is a 10-item scale that measures a general sense of perceived self-efficacy. The scale aims to predict coping with daily hassles and adaptation after experiencing stressful life events. An exemplar item from the GSE is, “I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough”. Participants respond to questionnaire items on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true), indicating the extent to which they agree with the statement. The total score of the measure is tallied by tallying the sum of all the items, which ranges from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-efficacy. The Cronbach’s alpha for the GSE ranged from 0.76 to 0.90, according to Schwarzer and Jerusalem [35]. For the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

2.2.3. Interpersonal Reactivity Index

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index [24] is a self-report questionnaire that consists of four 7-item subscales, including perspective-taking (PT), fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress. For the purpose of this study, only the PT subscale was used in the analyses. The perspective-taking (PT) scale measures the cognitive tendency for adopting the psychological perspective of others. An exemplary item for the PT subscale is, “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision”. Participants responded to the seven items on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (does not describe me well) to 4 (describes me very well). The rating scores were summed to provide the score for the measure of perspective-taking. According to Davis [24], Cronbach’s alpha for the PT subscale was 0.71 for males and 0.75 for females. For the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.70 for the PT subscale.

2.3. Data Analysis

The measures of central tendency and variability of the main study variables (self-efficacy, perspective-taking, and three aspects of job satisfaction) were summarized using descriptive statistics. The demographic variables were examined for their associations with the main study variables. Between subjects t-tests were performed to examine gender differences in the main study variables. The relations among the main study variables were first examined by a bivariate correlation analysis. Based on the results of the bi-variate correlational analysis, separate regression analyses were performed to explore how self-efficacy and perspective-taking jointly related to three aspects of job satisfaction and whether there was an interaction effect between self-efficacy and perspective-taking in the three aspects of job satisfaction.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

For general job satisfaction measured by the MSQ, the average score for general satisfaction in the current DSPs sample was 69.1 (SD = 17.17). The mean score for intrinsic satisfaction was 42.27 (SD = 10.16), and that for extrinsic was 19.92 (SD = 6.01). According to the reported norms of a reference sample comprised of janitors and maintenance men in the MSQ’s scoring manual [34], the average for general satisfaction was 78.01 (SD = 11.51), intrinsic satisfaction 49.03 (SD = 6.91), and extrinsic 20.99 (SD = 4.86). Thus, the current sample scored lower in general, intrinsic, and extrinsic job satisfaction compared to the reference reported by Weiss et al. [34]. The average score for the self-report self-efficacy in the current sample was 31.49 (SD = 6.50). The mean self-efficacy score in the present sample was close to the average self-efficacy score of 29.48 (SD = 5.13) reported by Schwarzer and Jerusalem [35]. The mean score for perspective-taking was 24.72 (SD = 5.49), which was also close to the mean score of the reference sample reported by Davis [24].

Although not a focus of this research (the sample was comprised predominantly of female DSPs), gender differences were observed only in the variable of self-efficacy. Female DSPs reported lower levels of self-efficacy compared to their male co-workers, t(72) = −3.15, p = 0.002. All the other demographic variables were not related to the job satisfaction. Thus, all the other demographic variables were not included in further analyses.

3.2. Correlations

Bi-variate correlation analysis indicated that the self-efficacy in DSPs was positively correlated with general job satisfaction, r = 0.39, p < 0.001; intrinsic job satisfaction, r = 0.43, p < 0.001; and extrinsic job satisfaction, r = 0.31, p = 0.004. Self-efficacy and perspective-taking in DSPs were also positively correlated, r = 0.45, p = < 0.0001. However, only intrinsic job satisfaction, but not extrinsic or general job satisfaction, was correlated with perspective-taking, r = 0.22, p = 0.049.

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

To explore if perspective-taking would moderate the relation between self-efficacy and job satisfaction in DSPs, a multiple regression analysis was performed. Three separate regression models were tested with self-efficacy as the main predictor, job satisfaction (general, intrinsic, and extrinsic, respectively) as the criterion variable for each of the three models, and perspective-taking as the moderator. Because there were gender differences in the variable of self-efficacy, gender was controlled in the regression models. The preliminary results showed that only the model predicting intrinsic job satisfaction revealed statistical significance, F (3, 59) = 4.60, p = 0.006, R2adj = 0.15, with self-efficacy showing a significant main effect on intrinsic job satisfaction, b = 0.35, SE = 0.12, t = 3.08, p = 0.003. Because the models for general and extrinsic job satisfaction did not reveal statistical significance, the further moderation analysis thus only focused on intrinsic job satisfaction.

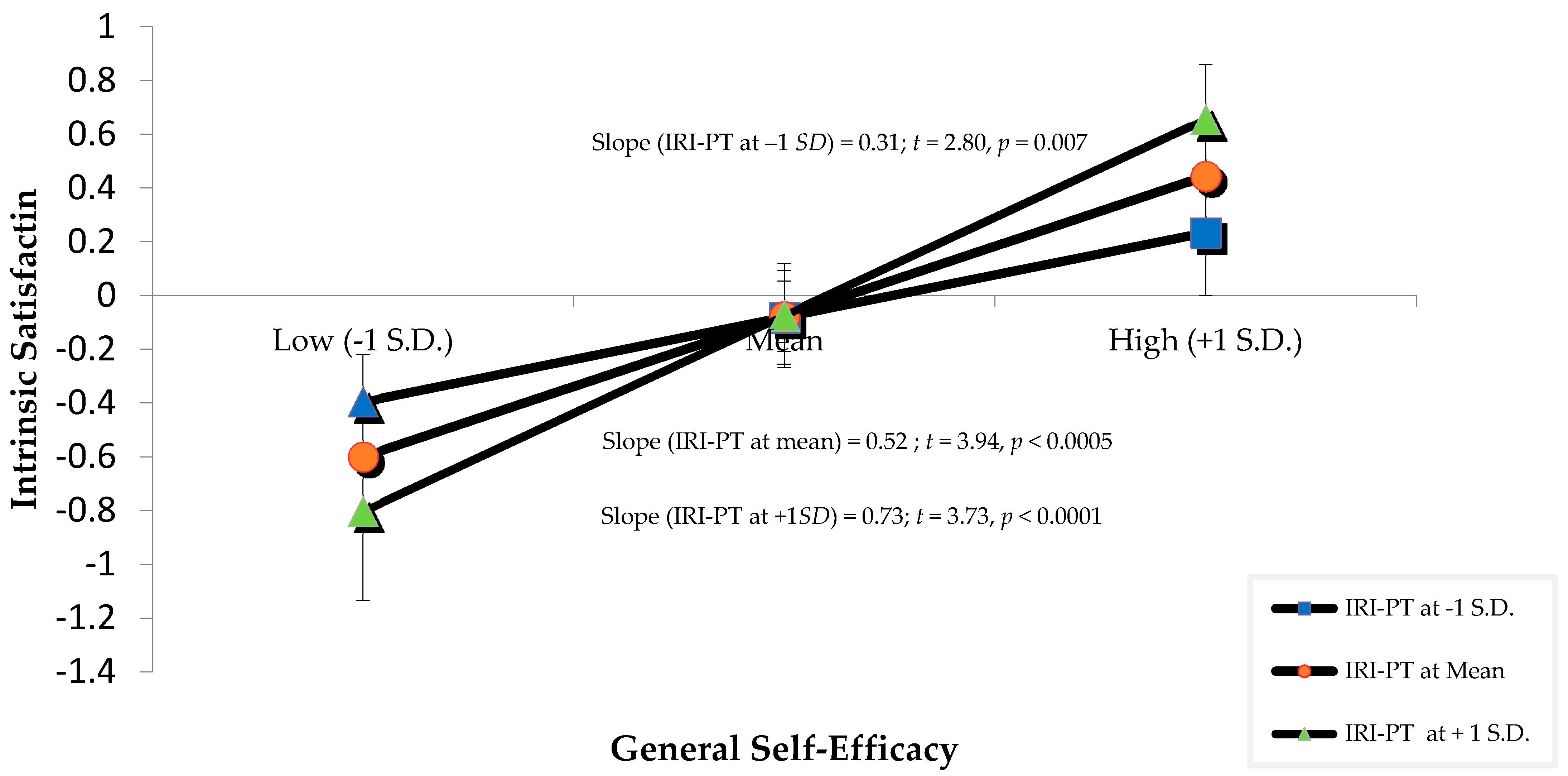

A further regression analysis adding the cross-product of self-efficacy and perspective-taking to the model indicated a significant interaction effect on intrinsic satisfaction, b = 0.21, SE = 0.09, t = 2.33, p = 0.024, F (4, 58) = 5.07, p = 0.001, R2adj = 0.21 (Table 2), suggesting that perspective-taking moderated the relation between self-efficacy and intrinsic satisfaction. Figure 1 summarizes this interaction, showing the prediction for intrinsic satisfaction from three levels of self-efficacy (−1SD, mean, +1SD) at three levels of perspective-taking (−1SD, mean, +1SD). Subsequent simple slope tests indicated that the association of self-efficacy with intrinsic satisfaction varied by levels of perspective-taking, such that higher levels of perspective-taking were associated with stronger links between self-efficacy and intrinsic satisfaction. The findings suggested that a general proclivity for perspective-taking when witnessing others in plight would reinforce the association between self-efficacy and intrinsic job satisfaction.

Table 2.

Results of a multiple regression analysis for the prediction of intrinsic satisfaction (N = 133).

Figure 1.

Prediction for intrinsic job satisfaction from three levels of general self-efficacy (−1SD, mean, +1SD) at three levels of perspective-taking (−1SD, mean, +1SD) and the effect of the interaction between general self-efficacy and perspective-taking (measured by the subscale of Perspective Taking of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, IRI-PT) predicting intrinsic job satisfaction. All the variables were standardized. Gender was controlled. Values on the Y-axis are Z scores.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine how individual differences in general self-efficacy and perspective-taking related to job satisfaction in DSPs. As well as this, the study examined if self-efficacy and perspective-taking exhibited an interaction effect on the job satisfaction reported by DSPs. The information is important to forging training programs that not only promote technical job skills but also empower DSPs to achieve a sense of satisfaction from their job tasks, which in turn may benefit quality care for individuals with DDs.

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The majority of the DSPs in the current sample were females, and a large percentage of DSPs were African American. With a few participants being older than 60, the DSPs were within the age range of 20 to 50. Nearly half of the participants had worked at the facility for over five years, which was relatively long compared to the high turnover rate and short tenure that are typical among the DSP workforce. It has been reported that, on average, less than 40% of DSPs are employed longer than 36 months [1,3], although information on the population demographics from a nationally representative sample has not yet been established [36]. This surprising result from the current sample could likely be explained by several factors. First, the governmental supported services center from which the current sample of DSPs were recruited is a state-run facility that offers state employee benefits, including retirement plans. Although the job is demanding and taxing, the incentive of a good retirement and benefits package might have motivated DSPs to be employed long-term at the facility. Additionally, it is a very large facility located in a fairly small town; thus, a lack of other employment opportunities in the area might also have contributed to the longer duration of employment in the current sample. Further, many DSPs had family members that also worked or had worked at the facility as DSPs. The familiarity of the working environment and climate might have contributed to the long employment in the participants.

Despite the employee benefits and a convenient and familiar working environment, DSPs in the current sample reported generally low levels of intrinsic, extrinsic, and general job satisfaction. For this reason, the length of the employment in the current sample did not reflect the levels of job satisfaction reported by the DSPs. Many issues in the direct support workforce might have negatively affected job satisfaction. DSPs have laborious and taxing job duties while caring for individuals with DDs who often need a significant amount of assistance and may display a variety of challenging behaviors, including self-injury [37], aggression [38], and difficulty communicating [39]. In addition, DSPs face many negative work experiences such as insufficient professional training, low pay, and understaffing issues [1,2,6,10,40]. Thus, there have been extensive reports of stress, negative health outcomes, burnout, and intention to resign, reflecting widespread job dissatisfaction [5,6,16,40,41,42,43].

4.2. Correlates for Job Satisfaction

The findings supported previous reports indicating that high levels of self-efficacy were associated with the sense of satisfaction with job [8,23,44]. Indeed, individuals with high levels of self-efficacy hold positive cognitive representations of the self and a sense of control over challenging situations; thus, they are less likely to feel stressed and overwhelmed, and are more likely to attain goals and achieve a sense of satisfaction about their lives and professions [8,16,17,20,22,45].

As well as this, the current results supported prior findings on the association of perspective-taking and job-related outcomes [25,26,27,28,46,47,48]. A propensity for taking the perspectives of others in need might have facilitated DSPs to cognitively understand the circumstances and needs of the individuals they were serving, which aided DSPs in offering care that addressed the individuals’ needs and in the regulation of distressing emotions due to the straining demands of the job tasks. In this way, DSPs who sought to understand the plight of the individuals they cared for were likely to receive positive feedback from the individuals they served and this indirectly enhanced the sense of reward and satisfaction from their service work.

As shown in the current sample, such experiences would plausibly be more relevant to the intrinsic, but not extrinsic, aspect of job satisfaction, because intrinsic job satisfaction involved one’s subjective perception of delight, aptitude, and professional growth associated with daily task demands, while extrinsic job satisfaction involved appraisals of factors external to the job tasks themselves [12,13,14,15]. The findings suggested that, compared to the extrinsic aspect, the intrinsic aspect of job satisfaction was a more immediate job variable that is associated with perspective-taking.

Although the literature has yet to thoroughly establish the relation between self-efficacy and perspective-taking, the current results indicated that self-efficacy and perspective-taking were positively related to each other. Self-efficacy is implicated with the belief in one’s own ability to effectively handle challenging circumstances, and such confidence in the self can be augmented by the skills of objectively and accurately perceiving the self in relation to others and the context—the process at the core of perspective-taking. The positive association pointed to the common underlying process of socio-cognitive reasoning about the self and others shared by self-efficacy and perspective-taking. Our findings added to the gap in the literature, addressing the relation between the two psychosocial correlates specifically in the population of DSPs. The findings also provided support for viewing self-efficacy and perspective-taking as personal resources that can be conducive to outcomes in a work environment, as posited by the conservation of resources perspective [30,31].

4.3. Interaction between the Two Psychosocial Correlates

Given that self-efficacy, perspective-taking, and intrinsic job satisfaction were mutually associated with one another, this study explored if there was an interaction effect between the two correlates—general self-efficacy and perspective-taking—on intrinsic job satisfaction. In light of the Conservation of Resources theory (COR) [30,31], we expected to find that self-efficacy and perspective-taking—two valuable psychosocial resources within the broad and objective context of challenging work circumstances—would augment each other and contribute to DSPs’ perception of job satisfaction. As predicted, the results of the multiple regression analysis revealed a significant interaction between self-efficacy and perspective-taking for the prediction of intrinsic job satisfaction. Specifically, as perspective-taking increased, the association between general self-efficacy and intrinsic satisfaction strengthened, suggesting a moderating role of perspective-taking. The findings suggested that self-efficacy and perspective-taking might complement each other in the process involved in reasoning about the self and others and in relation to a broad, shared environmental demands facing DSPs. A proclivity for perspective-taking when witnessing others in needs would facilitate DSPs to provide services that addressed the needs of individuals they served and support emotional regulation in DSPs when facing daily challenges of their service work, which, as discussed previously, had direct relevance for a sense of intrinsic job satisfaction. Additionally, as discussed previously, the competence in perspective-taking also provided DSPs with the tools to be aware of one’ own task efficiency and accomplishment, such that a sense of efficacy could be framed in a fair and objective light in relation to group and broad-based perceptions of DSPs’ roles. Indeed, self-efficacy and perspective-taking appeared to be beneficial resources and important components that worked in concert to enhance the subjective appraisal of self-actualization and self-accomplishment derived from the daily job tasks of DPSs. Based on the theoretical perspective of Hobfoll’s COR [30,31], the two psychosocial correlates need to be examined not merely as subjective personal characteristics but rather as key resource components in relation to the objective and commonly perceived. Therefore, it would be advantageous to highlight the importance of both self-efficacy and perspective-taking in job trainings that address the objective and broad perceptions of job demands facing DSPs in hopes of increasing their perceived levels of intrinsic job satisfaction.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Certain limitations in the present study warrant precautions warrant precautions when trying to generalize the findings to a greater population of DSPs. The primary limitation concerns the utilization of a cross-sectional design in the present study, which is inherently limited in determining the directions of the associations between the study variables. For example, the current data could not determine if it was self-efficacy that predicated intrinsic job satisfaction, or if it was the perceived satisfaction at work that led to a sense of control over work situations. Future research can benefit from adopting longitudinal designs by gathering data at different time points to address the temporal relations between study variables. Second, the sample size for the present study was relatively small and the majority of participants were female DSPs, rendering limited information on male DSPs experiences. Further, all the current sample of DSPs were recruited from the same facility with a unique climate and culture, which might have limited the variabilities in study variables. For example, DSPs receive fairly good benefits being employed by the state, which was not typical for DSPs working in other settings [3]. To increase the generalizability of the findings, future research can improve by collecting a larger sample from different facilities with more balanced composition of both female and male DSPs. Additionally, the measures used in the study were self-report measures, which could undermine the quality of data potentially due to social desirability. Future research can address this issue by employing implicit measures and controlling social desirability.

Despite the limitations, the present study provided important information on the psychosocial correlates that were important to job satisfaction in DSPs. The findings shed light on training programs aimed to improve job satisfaction in DSPs, which in turn may contribute to the quality of care for individuals with needs and solutions for the workforce issues of DSPs. In fact, research has outlined that interventions aimed at training self-efficacy can support skill transfer from an instructional to a work environment [48]. Approaches such as to strengthening logical verification and verbal persuasion [49] and managing attributions for unsuccessful outcomes to unreliable resources and causes [50] can be helpful to boost employees’ sense of self-efficacy. Research has also suggested that enhancing perspective-taking serves as a means to stimulate job performance [51]. Training programs can involve introducing and structuring circumstances for employees to directly interact with clients served and providing guidance for employees to accurately and objectively process clients’ perspectives [47]. Job training for DSPs has been reported as insufficient and the need for improvement has been enormous. One way that the training should be improved is by focusing on strengthening and fostering greater senses of self-efficacy and perspective-taking in DSPs.

6. Conclusions

Adding to the scarce literature on psychosocial correlates for job satisfaction in the population of DSPs, the present study examined self-efficacy and perspective-taking and their relation to job satisfaction. The findings indicated that a general sense of self-efficacy was positively associated with job satisfaction reported by DSPs, and the association between self-efficacy and intrinsic job satisfaction was moderated by perspective-taking. The findings suggested that fostering perspective-taking and enhancing self-efficacy in DSPs may prove to be beneficial in bolstering job satisfaction in DSPs. Such psychosocial approaches to improving outcomes in job satisfaction may in turn improve the quality of care for individuals with DDs and ultimately contribute to resolving the widespread DSP workforce issues and the national public health crisis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.F. and H.-C.L.; methodology, H.-C.L. and S.N.F.; formal analysis, H.-C.L. and S.N.F.; resources, S.N.F.; data curation, H.-C.L. and S.N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.F., H.-C.L., H.J.H. and M.K.K.; writing—review and editing, H.J.H. and M.K.K.; visualization, H.-C.L.; supervision, H.-C.L.; project administration, S.N.F. and H.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the direct support professionals who provided their responses to the measures of this study. The authors would also like to thank the members of the Developmental Science Laboratory at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette for various aspects of this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- National Core Indicators. 2017 Staff Stability Survey Report. Available online: https://www.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/core-indicators/2017_NCI_StaffStabilitySurvey_Report.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Wolf-Branigin, M.; Wolf-Branigin, K.; Israel, N. Complexities in Attracting and Retaining Direct Support Professionals. J. Soc. Work. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 6, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, J. America’s Direct Support Workforce Crisis: Effects on People with Intellectual Disabilities, Families, Communities and the U.S. Economy; President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities. Available online: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/programs/2018-02/2017%20PCPID%20Full%20Report_0.PDF (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Piko, B.F. Burnout, role conflict, job satisfaction and psychosocial health among Hungarian health care staff: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2006, 43, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemse, B.; Smit, D.; De Lange, J.; Pot, A.M. Nursing Home Care for People with Dementia and Residents’ Quality of Life, Quality of Care and Staff Well-Being: Design of the Living Arrangements for People with Dementia (LAD)—Study. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, S.A.; Lakin, K.C.; Anderson, L.; Kwak Lee, N.; Lee, J.H.; Anderson, D. Prevalence of mental retardation and developmental disabilities: Estimates from the 1994/1995 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplements. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2001, 106, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Research. Available online: http://www.ncddr.org/new/announcements/lrp/fy2005-2009/exec-summ.html#dd (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Randhawa, G. Relationship between Self-Efficacy with Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis. Bus. Rev. 2003, 10, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Jayachandran, C.; Babin, B.J.; Peterson, R.T. Empathy, nonverbal immediacy, and salesperson performance: The mediating role of adaptive selling behavior. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-García, G.; Ayala, J.-C. Relationship between Psychological Capital and Psychological Well-Being of Direct Support Staff of Specialist Autism Services. The Mediator Role of Burnout. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B. The Motivation to Work; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarjalal, E.; Ghafari, M.; Firouzeh, M.M.; Farahaninia, M. Intrinsic and extrinsic determinants of job satisfaction in the nursing staff: A cross-sectional study. Arvand J. Health Med. Sci. 2017, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfield, R.R. Does revisiting the intrinsic and extrinsic subscales of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form make a difference? Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektas, C. Explanation of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Job Satisfaction via Mirror Model. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2017, 5, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, W.; Welko, T.; Brouwers, S. Effects of aggressive behavior and perceived self-efficacy on burnout among staff of homes for the elderly. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2001, 22, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molero, M.D.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Gázquez, J.J. Analysis of the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem on the Effect of Workload on Burnout’s Influence on Nurses’ Plans to Work Longer. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.; Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S. Impact of self-efficacy on psychological well-being among undergraduate students. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2015, 2, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Soysa, C.K.; Wilcomb, C.J. Mindfulness, Self-compassion, Self-efficacy, and Gender as Predictors of Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Well-being. Mindfulness 2013, 6, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Planta, A.; Cicotto, G. The role of job satisfaction, work engagement, self-efficacy and agentic capacities on nurses’ turnover intention and patient satisfaction. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 39, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmud, S.; Pasundan, B.S.T.I.E. The Influence of Self-Efficacy on Satisfaction and Work-Related Performance. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2018, 4, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.I.; Stiff, J.B.; Ellis, B.H. Communication and empathy as precursors to burnout among human service workers. Commun. Monogr. 1988, 55, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.; Whittington, R.; Perry, L.; Eames, C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn. Res. 2017, 6, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, L.D.; Pohl, S.; Saiani, L.; Battistelli, A. Empathy in the emotional interactions with patients. Is it positive for nurses too? J. Nurs. Educ. Pr. 2013, 4, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.B.; Yao, X. Clinical Empathy as Emotional Labor in the Patient-Physician Relationship. JAMA 2005, 293, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.R.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Huntington, J.L.; Lawson, K.L.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. How Do Distress and Well-being Relate to Medical Student Empathy? A Multicenter Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Hobfoll, S. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.B.; Davidson, O.B.; Margalit, M. Personal Resources, Hope, and Achievement Among College Students: The Conservation of Resources Perspective. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 16, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Stevens, N.R.; Zalta, A.K. Expanding the Science of Resilience: Conserving Resources in the Aid of Adaptation. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W.; Lofquist, L.H. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire; University of Minnesota Industrial Relations Center: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute. Who are direct-care workers? 2011. Available online: https://phinational.org/wpcontent/uploads/legacy/clearinghouse/NCDCW%20Fact%20Sheet-1.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- MacLean, W.E.; Dornbush, K. Self-Injury in a Statewide Sample of Young Children With Developmental Disabilities. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 5, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felce, D.; Kerr, M. Investigating low adaptive behaviour and presence of the triad of impairments characteristic of autistic spectrum disorder as indicators of risk for challenging behaviour among adults with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 57, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevan, F. Challenging behaviour and communication difficulties. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2003, 31, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.; Clarke, S.; Sloane, U.M.; Sochalski, J.; Silber, J.H. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatton, C.; Emerson, E.; Rivers, M.; Mason, H.; Mason, L.; Swarbrick, R.; Kiernan, C.; Reeves, D.; Alborz, A. Factors associated with staff stress and work satisfaction in services for people with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1999, 43, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, A.; Larson, S.; Edelstein, S.; Seavey, D.; Hoge, M.A.; Morris, J. A Synthesis of Direct Service Workforce Demographics and Challenges across Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities, Aging, Physical Disabilities, and Behavioral Health; National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center; Available online: https://nadsp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Cross-DisabilitySynthesisWhitePaperFinal.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Lopes, A.R.; Nihei, O.K. Burnout among nursing students: Predictors and association with empathy and self-efficacy. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20180280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.S.; Jeoung, Y.; Lee, H.K.; Sok, S.R. Relationships Among Communication Competence, Self-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction in Korean Nurses Working in the Emergency Medical Center Setting. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, N.; Rastogi, R. Assessing the relationship between emotion al intelligence, occupational self-efficacy and organizational commitment. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 35, 23–102. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lam, W.; Woods, S.A. Standing in my customer’s shoes: Effects of customer-oriented perspective taking on proactive service performance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 92, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Axtell, C.M. Seeing another viewpoint: Antecedents and outcomes of employee perspective taking. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Marinova, S.V. What predicts skill transfer? An exploratory study of goal orientation, training self-efficacy and organizational supports. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2005, 9, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, D.D.; Dobbins, G.H.; Trahan, W.A. The trainer-trainee interaction: An attributional model of training. J. Organ. Behav. 1991, 12, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Berry, J.W.; MacLean, T.L.; Behnam, M. The Necessity of Others is The Mother of Invention: Intrinsic and Prosocial Motivations, Perspective Taking, and Creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).