Abstract

Competitive bodybuilders undergo strict dietary and training practices to achieve an extremely lean and muscular physique. The purpose of this study was to identify and describe different dietary strategies used by bodybuilders, their rationale, and the sources of information from which these strategies are gathered. In-depth interviews were conducted with seven experienced (10.4 ± 3.4 years bodybuilding experience), male, natural bodybuilders. Participants were asked about training, dietary and supplement practices, and information resources for bodybuilding strategies. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using qualitative content analysis. During the off-season, energy intake was higher and less restricted than during the in-season to aid in muscle hypertrophy. There was a focus on high protein intake with adequate carbohydrate to permit high training loads. To create an energy deficit and loss of fat mass, energy intake was gradually and progressively reduced during the in-season via a reduction in carbohydrate and fat intake. The rationale for weekly higher carbohydrate refeed days was to offset declines in metabolic rate and fatigue, while in the final “peak week” before competition, the reasoning for fluid and sodium manipulation and carbohydrate loading was to enhance the appearance of leanness and vascularity. Other bodybuilders, coaches and the internet were significant sources of information. Despite the common perception of extreme, non-evidence-based regimens, these bodybuilders reported predominantly using strategies which are recognized as evidence-based, developed over many years of experience. Additionally, novel strategies such as weekly refeed days to enhance fat loss, and sodium and fluid manipulation, warrant further investigation to evaluate their efficacy and safety.

1. Introduction

Competitive bodybuilders undergo strict dietary and training practices to achieve an extremely lean, muscular and symmetrical physique [1]. Along with resistance and aerobic exercise [2], targeted energy and macronutrient intakes are followed to accumulate muscle mass in the off-season, and reduce fat mass in the in-season [1]. However the specific dietary strategies employed by bodybuilders and their underpinning rationale remain poorly understood.

Contemporary literature examining the dietary intakes of bodybuilders is limited [1], and given the unique nature of competitive bodybuilding, it may be inappropriate to draw dietary parallels from other sports. Although bodybuilders have been reported to follow extreme, non-evidence-based approaches, several dietary strategies developed in bodybuilding have recently been scientifically validated, such as frequent dosing of protein [3], and intake of protein around training [4]. Identifying the dietary strategies of modern bodybuilders, and exploring their underpinning rationale, will provide exercise, sport and nutrition practitioners with an understanding of current bodybuilding methods and insights to assist with negotiating practical and effective ways to work towards bodybuilding goals. Furthermore, identifying such strategies will also generate hypotheses for future research.

In-depth interviews allow a deep exploration of the discussed topic, enable the researchers to enter new areas and produce rich data, with an additional benefit of uncovering practices that had not been anticipated [5,6]. The purpose of this study was to use in-depth interviews to identify and describe different dietary strategies used by male, natural bodybuilders, their rationale, and the sources of education from which these strategies are gathered.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants were purposively selected by the research team based on expertise and experience in competitive bodybuilding. To recruit participants, experienced bodybuilders known to the researchers from previous studies were invited to participate. Adverts were placed on the website and social media page of Australasian Natural Bodybuilding (ANB), and distributed at the ANB national titles in October 2015. To be included, participants needed to be male, natural (drug-free) bodybuilders, aged 18 years and older, with five or more years of bodybuilding experience. Participants were required to have competed in the bodybuilding category at national or international level contests of drug-tested federations.

2.1. Procedures

The interviews were conducted by three members of the research team between March 2015 and February 2016. Interviews (78–124 min) were held by telephone or Skype. The combined duration of all interviews was 11 h. Interviews captured participant demographic characteristics including age, years of bodybuilding experience, number of previous competitions, and competition success. Participants were asked about their training, dietary, supplement and competition preparation practices, the rationale behind these practices, and where they obtained information about nutrition and training. By the end of the last interview, no new major themes were emerging. Saturation was confirmed following coding of the data, therefore the decision was made to cease further data collection.

2.2. Analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by a commercial transcription service (waywithwords.com). Transcripts were returned to participants for verification and correction to ensure the transcription correctly reflected the content of their interview. One participant returned the transcript with minor emendations, which was included in the analysis. Notes were taken during all interviews and used to clarify transcription errors, and to confirm the meaning of spoken phrases during the coding process. To protect the identity of the participants, a pseudonym was used in the final transcripts. All interviews were conducted prior to thematic analysis via qualitative content analysis using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo version 10.0, QSR International PTY Ltd., Doncaster, Australia, 2012). Coding was undertaken by one researcher (LM) with assistance from a second (FE) and overseen by a third researcher experienced in qualitative research (JG), who reviewed any queries. As coding of data proceeded, underlying themes emerged as participants discussed topics introduced by the interviewers, and was not constrained by the original structure of the interview. Identification of themes recurring through and across interviews was achieved through a process of reading, coding, code category refinement, rereading and code checking, and analysis of developing concepts. A coding journal with an audit trail of changes in coding and code refinement was maintained by the primary coder (LM) to maintain transparency of the qualitative analysis process.

Counts of coded talk were available from the analysis software by grouping for diet, training, supplements, and information and education. Counts within themes could have more than one section of speech by the same participant. To avoid researcher bias during the data interpretation process based on preconceived ideas of bodybuilding practices, identified themes were sent to participants, who confirmed correct interpretation.

Ethical approval was received from the University of Sydney Human Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was provided by all participants. Participation was voluntary and identity of participants and confidentiality of their responses was ensured.

3. Results

A total of seven bodybuilders (10.4 ± 3.4 years bodybuilding experience) meeting inclusion criteria responded to advertisements and consented to participate. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Four participants had competed at national, and three at international level. Two participants had competed professionally, with an additional one participant eligible to compete professionally. Example quotes are presented in Table 2. Selected quotes were representative of themes identified during interviews.

Table 1.

Individual participant characteristics of seven experienced male, natural bodybuilders participating in in-depth interviews.

Table 2.

Thematic summary of dietary practices and sources of dietary education, in seven experienced male, natural bodybuilders participating in in-depth interviews.

3.1. Diet

3.1.1. Off-Season

All participants consumed four to six meals per day, with a targeted energy and macronutrient intake aimed to support muscular hypertrophy, “I’ve got 250 [g/day] protein, and at the moment I’ll divvy my fats and carbs up, so 250 [g] protein, 680 [g] carb and about 100, 110 [g] on fats, somewhere there,” (Keith). Each meal featured a large serving of a high protein food and a large serving of vegetables, “In the morning I start off with 100 g of oats and six whole eggs. That’s at around about 7:00 a.m. At 9:30 a.m. will be 200 g of salmon and 200 g of green veg,” (Luke). The off-season diet contained a wide variety of foods, including processed foods such as ice cream, and was less regimented than the in-season.

3.1.2. In-Season

While the pattern and style of the diet was similar to the off-season, the in-season intake was more structured, “It’s more structured, it’s perfect” (Kyle), and usually carefully measured, “I will split a grain of rice, if it made it hit exactly the grammage (sic) I want,” (Keith). Serving sizes were also reduced as competition approached.

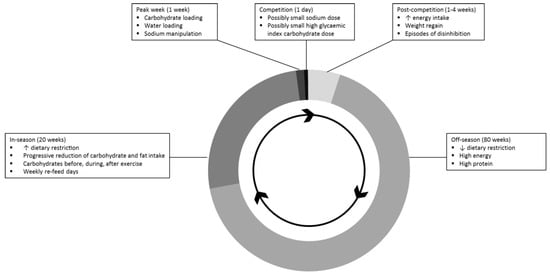

Progressive reductions in carbohydrate and fat intake were used to create then maintain an energy deficit to elicit fat loss (Figure 1). Protein intake remained similar to the off-season to prevent loss of lean mass. Carbohydrate intake was carefully timed around exercise (pre-, during and post-training) to ensure training was optimized.

Figure 1.

Doughnut chart representation of the stages of bodybuilding preparation, including key dietary strategies used, as reported by seven male, competitive natural bodybuilders participating in in-depth interviews. Duration of stages are approximate and vary between bodybuilders.

3.1.3. Refeed Days

Refeed days were commonly used during the in-season and primarily aimed to increase energy intake through elevated carbohydrate consumption. Participants discussed positive outcomes including increased glycogen stores which aid training performance, mental recovery, and prevention of further adaptive downgrades in energy expenditure, stimulating weight loss. One participant described it as a “metabolic jumpstart” (Oliver). Compared to preparations without refeed days, participants discussed consuming more total energy, over a shorter preparation, achieving better fat loss and muscle retention using weekly refeed days.

3.1.4. Peak Week

The week prior to the contest was defined as a “peak week”, where particular short-term strategies were used to achieve the leanest possible appearance. Six participants used a modified carbohydrate loading regimen (tapered training and increased carbohydrate intake) [7] in order to increase glycogen and theoretically increase muscle volume. Four participants had previously used the classic loading method, which involved a three-day glycogen depletion and then super-compensation [8], however found this did not produce significant changes in appearance, describing this method as, “stressful,” (Ben) “mentally that would be really bad,” (Kyle) and, “you’re just a wreck” (Luke).

All seven participants discussed the practice of water loading and cutting during peak week. Users of this strategy consumed more than 10 L of water per day early in the week, then reduced water intake each day leading into the contest. The rationale for this strategy was to increase fluid excretion and to “go after subcutaneous water” (Will), which would purportedly provide a leaner, more vascular appearance. Results were not effective enough for these participants to warrant continuation of this strategy in subsequent competition preparations. Other participants commented that the idea of water loading and cutting does not make sense physiologically: “muscle is about 70% water. If you were dehydrated, the muscles are going to look smaller as well,” (Harry).

Sodium manipulation was another strategy used during the peak week to reduce body water and produce a leaner appearance. Three participants discussed previously using this strategy, whereby sodium intake was greatly increased for three days, followed by a complete restriction of salt for three days. However, they each reported that the results were inconsistent, and discontinued the strategy.

3.1.5. Competition Day

Six participants discussed diet strategies used on the day of competition. Two consumed sodium prior to posing on stage to get a greater “pump”. Small doses of high glycemic index carbohydrates were consumed by two participants. One justified this by saying, “That was just to keep you ticking, when you’re feeling that depleted, just to keep you propped up,” (Oliver) while the other participant commented, “That’s for sugars, to get the pump” (Kyle). Two participants did not change from their usual intake on competition day.

3.1.6. Post-Competition

Participants reported the post-competition diet was more relaxed (n = 5), and included some “treat” foods not consumed during the in-season. Overindulgence and the experience of feeling physically sick from the change in diet pattern (n = 2) was reported. Weight regain was common and could be substantial (8–10 kg over three weeks in one case). Limited time off dieting was reported by three participants to avoid detrimental physique changes. Participants reported negative changes in physique were common post-competition.

3.2. Supplements

All participants used one or more dietary supplements. In total, 18 different supplement types were mentioned. Creatine (3–15 g/d) was used by all participants with doses consumed either pre- or post-workout, with a meal, or a combination of these. Protein powders were also used by all participants either as a post-training supplement (n = 4) or as a source of protein during meals (n = 4). “Preworkout” supplements designed to stimulate enhanced training was discussed by four participants, one of which used these for their caffeine content, while the others discontinued use due to side effects (insomnia, increased and variable heart rate, and increased respiratory rate). Participants reported these experiences were: “absolutely horrible” (Ben), “I just can’t stand it, frankly,” (Will) and “it’s counterproductive, so I don’t use it” (Will). Other supplements more commonly used were fish oil (four participants), glutamine (three participants) and testosterone boosters (three participants).

3.3. Sources of Education

The most commonly reported sources of education were the internet, including bodybuilding, strength and conditioning websites and forums (n = 5), successful bodybuilders (n = 4), and bodybuilding coaches (n = 4). The quality of information available on the internet was considered to be both reputable and non-reputable. Concerns were raised by two participants regarding information on social media, where images and information may be unrealistic and deceptive, and potentially damaging for novices. Bodybuilding coaches were also commonly used, although one participant commented on the varying levels of coach knowledge, with many relying on their own competition experience.

4. Discussion

The rationale and use of several key dietary strategies emerged from this study, including regular doses of protein throughout the day to maximize accrual and maintenance of lean mass, and utilizing carbohydrate foods as a fuel source pre-, during and post-exercise. Weekly refeed days were implemented during the in-season, to provide both a psychological rest and reportedly assist with fat loss. During the peak week, bodybuilders followed extreme strategies including water and sodium manipulation in an attempt to achieve the leanest physique.

Throughout both the off-season and in-season, participants reported consuming large, frequent servings of protein to build and maintain muscle mass, which is empirically supported in the research literature [3]. The optimal dose to achieve this maximal muscle protein synthesis is accepted to be 20–30 g of high quality protein [3,9], with studies supporting that protein ingestion above this dose is oxidized [9]. Recent findings suggest the amount of muscle mass trained may be a determinant of protein requirements post-exercise. Greater myofibrillar fractional synthetic rate was achieved with a 40 versus 20 g dose of whey protein following whole-body resistance exercise [10]. Therefore, a dose up to 40 g may produce increased protein synthesis following resistance exercise incorporating large amounts of muscle, such as those followed by bodybuilders.

The high-protein meals consumed by participants in this study likely exceeded the 20–40 g dose for maximal protein synthesis, potentially resulting in increased protein oxidation. However, the anabolic response to protein ingestion is a combination of protein synthesis and breakdown [11]. Greater protein net balance has been produced from a 70 g versus 40 g dose of protein, primarily by decreasing the rate of protein breakdown [11]. Therefore, the frequent, higher-dosed protein meals consumed by bodybuilders may not only assist in supporting protein synthesis, but also in reducing protein degradation during heavy resistance training. Furthermore, protein consumed by participants was primarily a part of a mixed nutrient meal, rather than a pure protein meal typically prescribed in the laboratory setting [3,9,10]. Carbohydrate and fat consumed in these meals would slow the digestive process, and amino acid delivery to muscle cells. Any protein consumed in addition to the optimal 20–40 g dose for muscle protein synthesis in these mixed meals may be utilized for anabolic processes over the time course of digestion.

A protein intake of 2.3–3.1 g/kg of fat-free mass has been suggested to be the most protective against losses of lean tissue during energy restriction in lean resistance trained athletes [12]. A higher protein requirement may be justified for bodybuilders during competition preparation, as they perform resistance and cardiovascular training, reduce energy intake, and achieve a lean condition [13]. Therefore, the higher protein intake during the in-season to prevent loss of muscle mass in these participants may be justified.

During the in-season period, carbohydrate consumption was carefully timed around exercise. Glycogen is an important fuel substrate during resistance training [14], with glycogen depletion reported to reduce exercise performance [15]. Carbohydrate supplementation before and during resistance exercise improves performance of high volume, exhaustive exercise [16,17], a characteristic typical of bodybuilding training [2]. During in-season energy restriction, carbohydrate consumption following resistance training would assist in the replenishment of muscle glycogen, facilitating improved recovery and enhanced capacity to maintain training volume and intensity in subsequent sessions [18]. Bodybuilders commonly perform multiple training sessions in a single day during the in-season, typically an aerobic and a resistance training session [2], therefore post-exercise carbohydrate ingestion would be important for maintaining training consistency.

Study participants discussed using a weekly refeed day during the in-season period to boost training performance, provide a mental rest, and assist in body fat reductions. Intermittent energy restriction for weight loss has garnered significant recent clinical and research interest due to its hypothetical capacity to alleviate metabolic and behavioral adaptations associated with reduced energy intake. These adaptations include increased appetite associated with neuropeptide expression [19,20,21], reduced energy cost of physical activity [22], and hormonal effects that promote fat deposition and loss of lean mass [19,20]. Intermittent energy restriction, or metabolic rest periods, have been shown to achieve similar weight and fat loss as continuous energy restriction, despite a higher overall energy intake [21,22]. Animal studies have shown that acute energy restoration (<24 h) can attenuate, or even abolish the orexigenic neuropeptide expression resulting from energy restriction [23,24]. The short-term restoration of energy balance, particularly through increased carbohydrate ingestion, would also increase intramuscular glycogen stores allowing greater resistance exercise performance [25].

During the peak week, participants discussed the use of several strategies to assist in achieving a lean, vascular appearance. Carbohydrate loading, and fluid and sodium manipulation had all been used by participants, with varying success. Only one empirical study has directly assessed changes in muscle girth from carbohydrate loading, finding no significant changes in relaxed or tensed muscle girths following a three-day carbohydrate depletion and subsequent three-day carbohydrate load [26]. This suggests carbohydrate loading may not produce the desired increase in muscle volume. Fluid and sodium manipulation to enhance visual appearance has not been empirically studied, however the desired improvement in muscle size and definition may not be obtained. Manipulating fluid intake to cause dehydration will result in a loss of fluid from all compartments, not just subcutaneous tissue [27,28]. Muscle water content is reduced [27], which may reduce muscle volume, an undesirable outcome for a competitive bodybuilder. Additionally, plasma volume is decreased with dehydration [27]; the common practice of “pumping up” prior to posing on stage may be less effective in increasing muscle size due to the detrimental effects of reduced plasma volume on muscle blood flow and volume [13]. Similarly, the manipulations in sodium consumption will not change the volume of the intracellular or extracellular compartments, only modifying urinary sodium output [29].

In the weeks following competition, participants reported an increased energy intake from a wider variety of foods, often leading to significant weight regain. Daily energy intake in the first two days post-competition was approximately twice that of the four weeks pre-competition in female bodybuilders, with an increase in body mass of 3.9 kg in the three weeks after competition [30]. Similarly, an average weight regain of 5.9 kg was reported in a group of male bodybuilders, with 46% of these participants reporting binge-eating episodes in the days immediately following competing [31].

Supplement use, predominantly creatine and protein powders, was common amongst the bodybuilders interviewed, while “pre-workout” formulas had been trialled, with unwanted side effects commonly reported. Protein and creatine supplementation have been demonstrated to be effective for increasing lean mass and strength [32,33]. The efficacy of so-called “pre-workout” supplements is yet to be confirmed. These products contain a combination of key ingredients such as creatine, caffeine, arginine, β-alanine and selected plant extracts [13,34,35]. Efficacy would be dependent on the supplement ingredients, and some produce side effects such as acute increases in blood pressure and difficulty sleeping [34].

Bodybuilders have historically relied on magazines, other successful competitors, and more recently the internet, for information on dietary strategies [1]. This study identified the internet, in particular bodybuilding and strength and conditioning websites and forums, as a primary source of education, as well as other bodybuilders and coaches. In addition to the internet [36], athletes have previously identified family members, other athletes, coaches and registered dietitians as important sources of information regarding nutrition and dietary supplements [37,38,39]. Dietitians were not identified as sources of information by participants in this study, suggesting that their role needs better promotion amongst bodybuilders. With skills in dietary assessment, planning and body composition measurement, as well as evidence-based strategies demonstrated to assist in the accrual of lean mass, dietitians have much expertise to provide bodybuilders, particularly novices who were considered by participants in this study to be vulnerable to inappropriate strategies promoted on the internet.

Study limitations include use of a small, homogeneous sample. Experienced bodybuilders were purposively sampled, therefore these results may not reflect the wider bodybuilding population, particularly inexperienced bodybuilders.

5. Conclusions

Despite the common perception that bodybuilders follow extreme, unproven methods, the experienced bodybuilders in this study reported predominantly using dietary strategies recognized as evidence-based. However, inexperienced bodybuilders may be vulnerable to more extreme strategies based on advice widely disseminated on the internet and social media.

Novel strategies identified in this study warrant further investigation. Intermittent energy restriction, and hormonal responses associated with short-term energy restoration, should be studied to determine benefits for weight loss whilst maintaining lean mass in both lean-athletic and obese populations. Peak week strategies implemented by bodybuilders, such as fluid and sodium manipulation, require further investigation to determine their efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sports Dietitians Australia.

Author Contributions

L.M. was involved in study design, data collection, analysis, writing. D.H. was involved in study design, data collection, writing. J.G. was involved in study design, analysis, writing. F.E. was involved in analysis, writing. H.O.C. was involved in study design, data collection, writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. H.O.C. receives payments from Sports Dietitians Australia for professional presentations delivered in a continuing education course for Sports Dietitians.

References

- Spendlove, J.; Mitchell, L.; Gifford, J.; Hackett, D.; Slater, G.; Cobley, S.; O’Connor, H. Dietary intake of competitive bodybuilders. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1041–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, D.A.; Johnson, N.A.; Chow, C.M. Training practices and ergogenic aids used by male bodybuilders. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areta, J.L.; Burke, L.M.; Ross, M.L.; Camera, D.M.; West, D.W.; Broad, E.M.; Jeacocke, N.A.; Moore, D.R.; Stellingwerff, T.; Phillips, S.M.; et al. Timing and distribution of protein ingestion during prolonged recovery from resistance exercise alters myofibrillar protein synthesis. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 2319–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribb, P.J.; Williams, A.D.; Carey, M.F.; Hayes, A. The effect of whey isolate and resistance training on strength, body composition, and plasma glutamine. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2006, 16, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Busaidi, Z.Q. Qualitative research and its uses in health care. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2008, 8, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.; van Royen, P.; Baker, R. Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2002, 11, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, W.M.; Costill, D.L.; Fink, W.J.; Miller, J.M. Effect of exercise-diet manipulation on muscle glycogen and its subsequent utilization during performance. Int. J. Sports Med. 1981, 2, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, J.; Saltin, B. Diet, muscle glycogen, and endurance performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 1971, 31, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.R.; Robinson, M.J.; Fry, J.L.; Tang, J.E.; Glover, E.I.; Wilkinson, S.B.; Prior, T.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Phillips, S.M. Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macnaughton, L.S.; Wardle, S.L.; Witard, O.C.; McGlory, C.; Hamilton, D.L.; Jeromson, S.; Lawrence, C.E.; Wallis, G.A.; Tipton, K.D. The response of muscle protein synthesis following whole-body resistance exercise is greater following 40 g than 20 g of ingested whey protein. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.Y.; Schutzler, S.; Schrader, A.; Spencer, H.J.; Azhar, G.; Ferrando, A.A.; Wolfe, R.R. The anabolic response to a meal containing different amounts of protein is not limited by the maximal stimulation of protein synthesis in healthy young adults. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E73–E80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, E.R.; Zinn, C.; Rowlands, D.S.; Brown, S.R. A systematic review of dietary protein during caloric restriction in resistance trained lean athletes: A case for higher intakes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, E.R.; Aragon, A.A.; Fitschen, P.J. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haff, G.G.; Koch, A.J.; Potteiger, J.A.; Kuphal, K.E.; Magee, L.M.; Green, S.B.; Jakicic, J.J. Carbohydrate supplementation attenuates muscle glycogen loss during acute bouts of resistance exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2000, 10, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepburn, D.; Maughan, R.J. Glycogen availability as a limiting factor in the performance of isometric-exercise. J. Physiol. 1982, 325, P52–P53. [Google Scholar]

- Haff, G.G.; Schroeder, C.A.; Koch, A.J.; Kuphal, K.E.; Comeau, M.J.; Potteiger, J.A. The effects of supplemental carbohydrate ingestion on intermittent isokinetic leg exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2001, 41, 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Haff, G.G.; Stone, M.H.; Warren, B.J.; Keith, R.; Johnson, R.L.; Nieman, D.C.; Williams, F.; Kirksey, K.B. The effect of carbohydrate supplementation on multiple sessions and bouts of resistance exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1999, 13, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, D.D.; Costill, D.L.; Fink, W.J.; Robergs, R.A.; Zachwieja, J.J. Glycogen resynthesis in skeletal-muscle following resistive exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainsbury, A.; Zhang, L. Role of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus in regulation of body weight during energy deficit. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 316, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainsbury, A.; Zhang, L. Role of the hypothalamus in the neuroendocrine regulation of body weight and composition during energy deficit. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 234–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seimon, R.V.; Shi, Y.C.; Slack, K.; Lee, K.; Fernando, H.A.; Nguyen, A.D.; Zhang, L.; Lin, S.; Enriquez, R.F.; Lau, J.; et al. Intermittent moderate energy restriction improves weight loss efficiency in diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seimon, R.V.; Roekenes, J.A.; Zibellini, J.; Zhu, B.; Gibson, A.A.; Hills, A.P.; Wood, R.E.; King, N.A.; Byrne, N.M.; Sainsbury, A. Do intermittent diets provide physiological benefits over continuous diets for weight loss? A systematic review of clinical trials. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 418 Pt 2, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Romsos, D.R. Neuropeptide y and corticotropin-releasing hormone concentrations within specific hypothalamic regions of lean but not ob/ob mice respond to food-deprivation and refeeding. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swart, I.; Jahng, J.W.; Overton, J.M.; Houpt, T.A. Hypothalamic npy, agrp, and pomc mrna responses to leptin and refeeding in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002, 283, R1020–R1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haff, G.G.; Lehmkuhl, M.J.; McCoy, L.B.; Stone, M.H. Carbohydrate supplementation and resistance training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2003, 17, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balon, T.W.; Horowitz, J.F.; Fitzsimmons, K.M. Effects of carbohydrate loading and weight-lifting on muscle girth. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1992, 2, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costill, D.L.; Cote, R.; Fink, W. Muscle water and electrolytes following varied levels of dehydration in man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1976, 40, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nose, H.; Mack, G.W.; Xiangrong, S.; Nadel, E.R. Shift in body fluid compartments after dehydration. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988, 65, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heer, M.; Baisch, F.; Kropp, J.; Gerzer, R.; Drummer, C. High dietary sodium chloride consumption may not induce body fluid retention in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2000, 278, 585–595. [Google Scholar]

- Walberg-Rankin, J.; Edmonds, C.E.; Gwazdauskas, F.C. Diet and weight changes of female bodybuilders before and after competition. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1993, 3, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, R.E.; Barlett, S.J.; Morgan, G.D.; Brownell, K.D. Weight-loss, psychological, and nutritional patterns in competitive male body-builders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1995, 18, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasiakos, S.M.; McLellan, T.M.; Lieberman, H.R. The effects of protein supplements on muscle mass, strength, and aerobic and anaerobic power in healthy adults: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, D.R.; Hamby, D.G.; Russel, W.; Harris, T. Long-term effects of creatine monohydrate on strength and power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1999, 13, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, A.W.; Hofheins, J.E.; Habowski, S.M.; Ferrando, A.A.; Gothard, M.D.; Lopez, H.L. Effects of a pre-workout supplement on lean mass, muscular performance, subjective workout experience and biomarkers of safety. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelmadine, B.; Cooke, M.; Buford, T.; Hudson, G.; Redd, L.; Leutholtz, B.; Willoughby, D.S. Effects of 28 days of resistance exercise and consuming a commercially available pre-workout supplement, no-shotgun(r), on body composition, muscle strength and mass, markers of satellite cell activation, and clinical safety markers in males. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2009, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaff, R.A.; Adams, V.J.; Crusoe, D.J.; Knous, J.L.; Baruth, M. Perceptions of athletic trainers as a source of nutritional information among collegiate athletes: A mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Kinesiol. Sports Sci. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, K.A.; Fung, T.S.; Reimer, R.A. Influence of performance level on dietary supplementation in elite canadian athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froiland, K.; Koszewski, W.; Hingst, J.; Kopecky, L. Nutritional supplement use among college athletes and their sources of information. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2004, 14, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scofield, D.E.; Unruh, S. Dietary supplement use among adolescent athletes in central nebraska and their sources of information. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).