Analyzing Parental Involvement in Youth Basketball

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

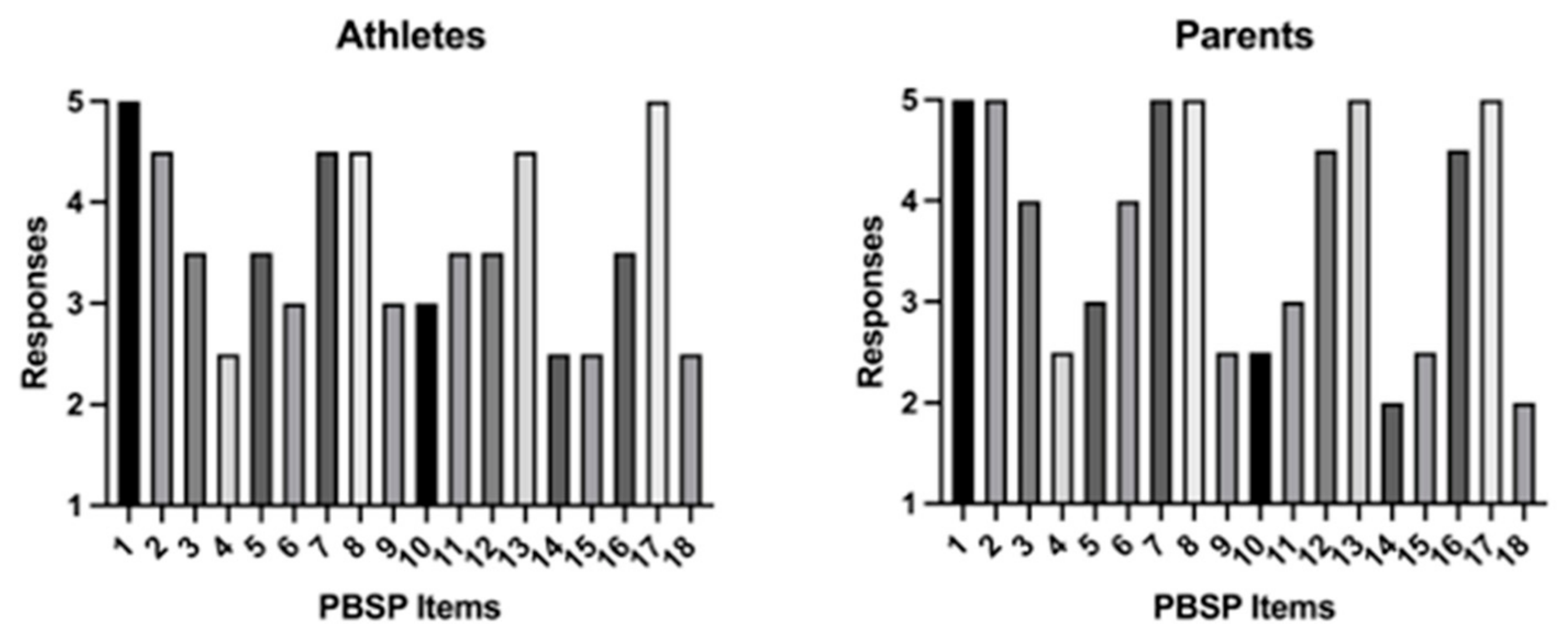

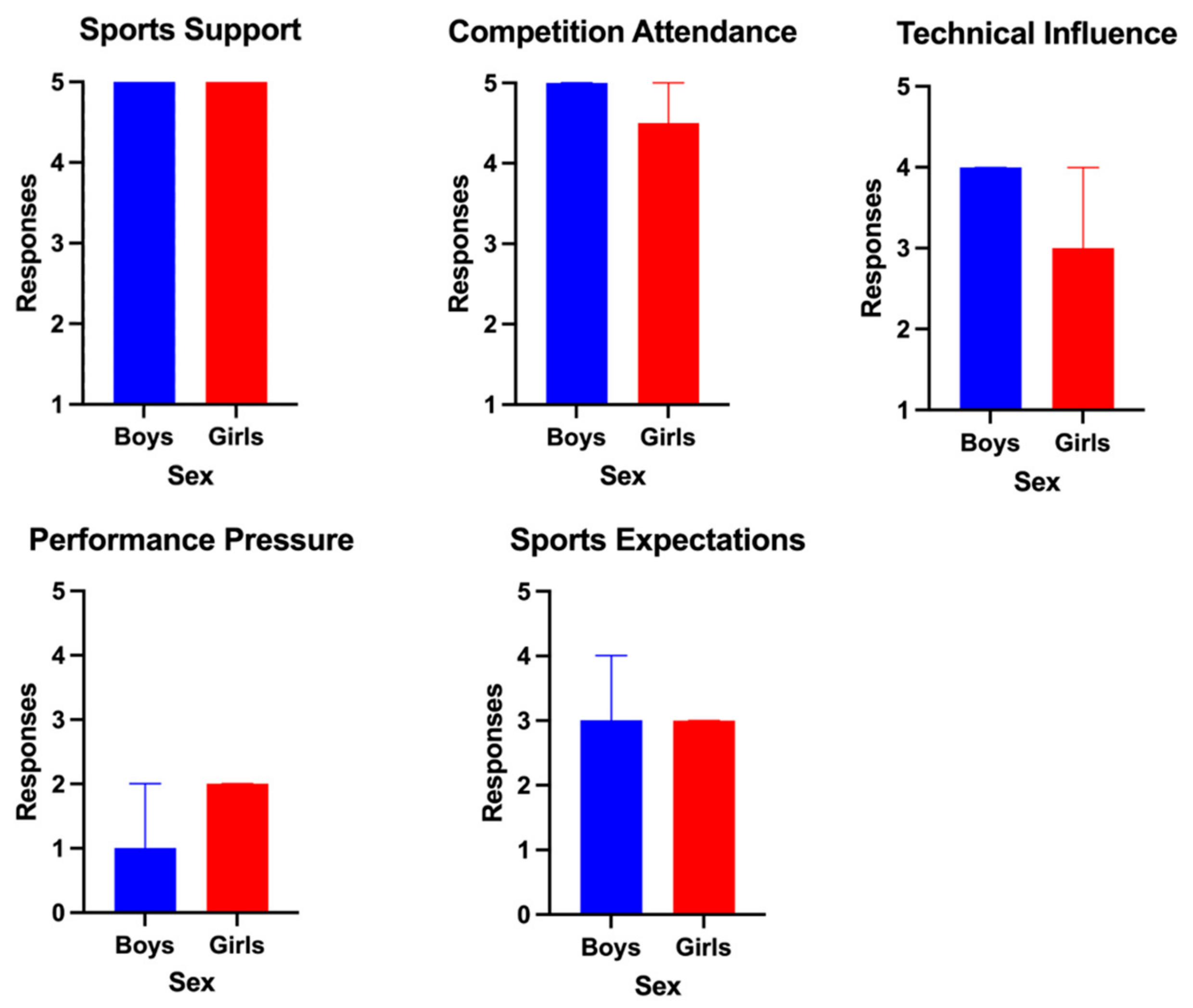

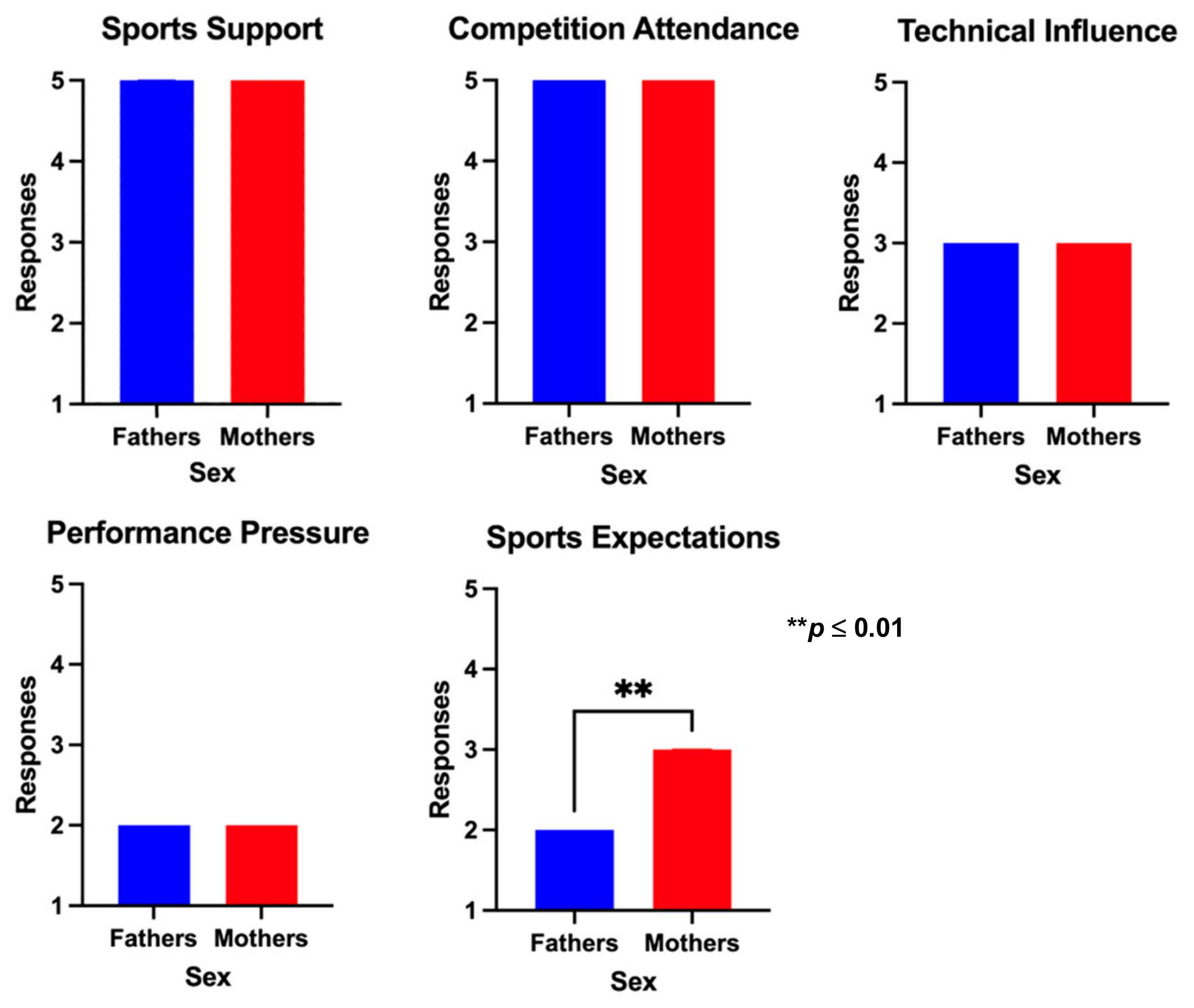

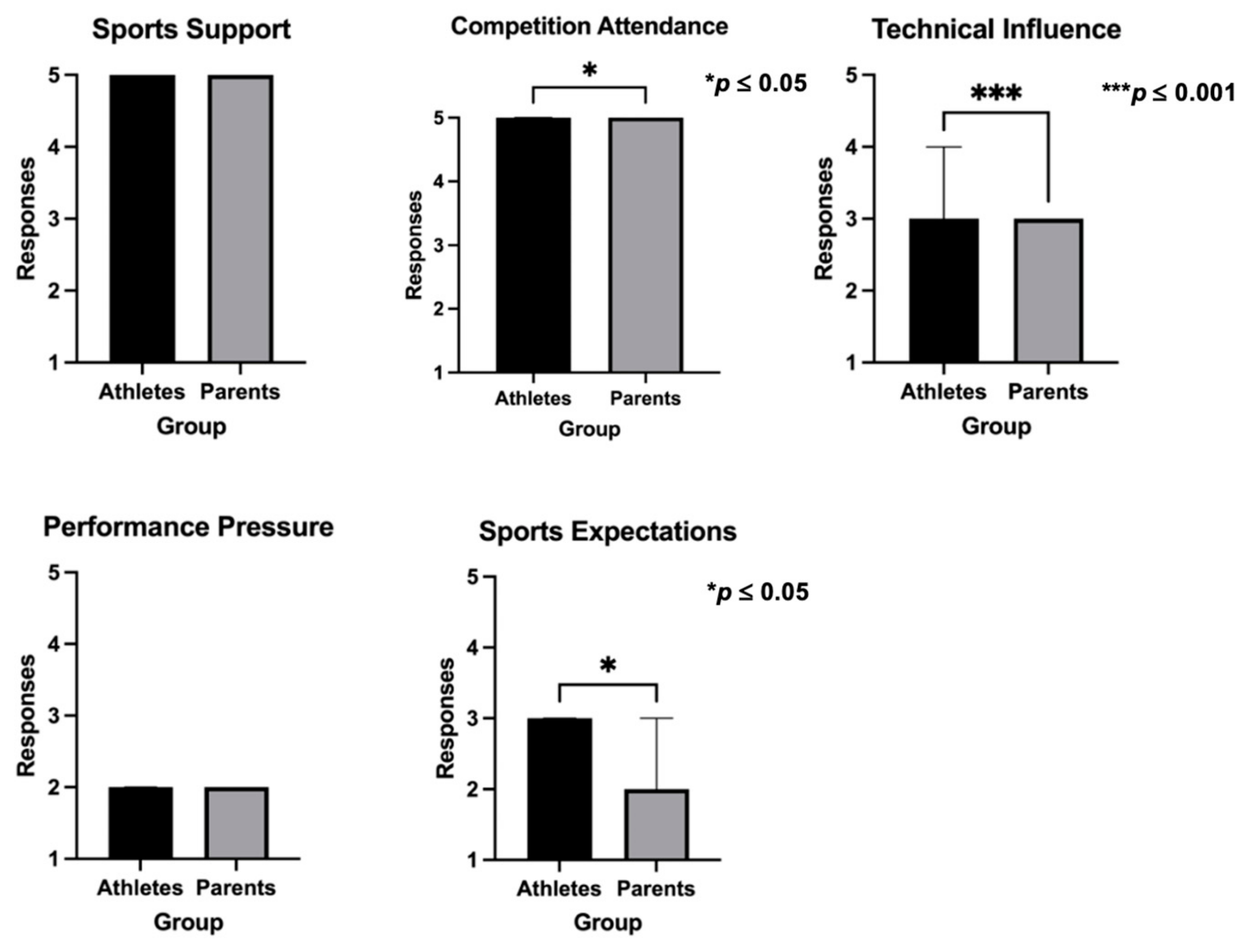

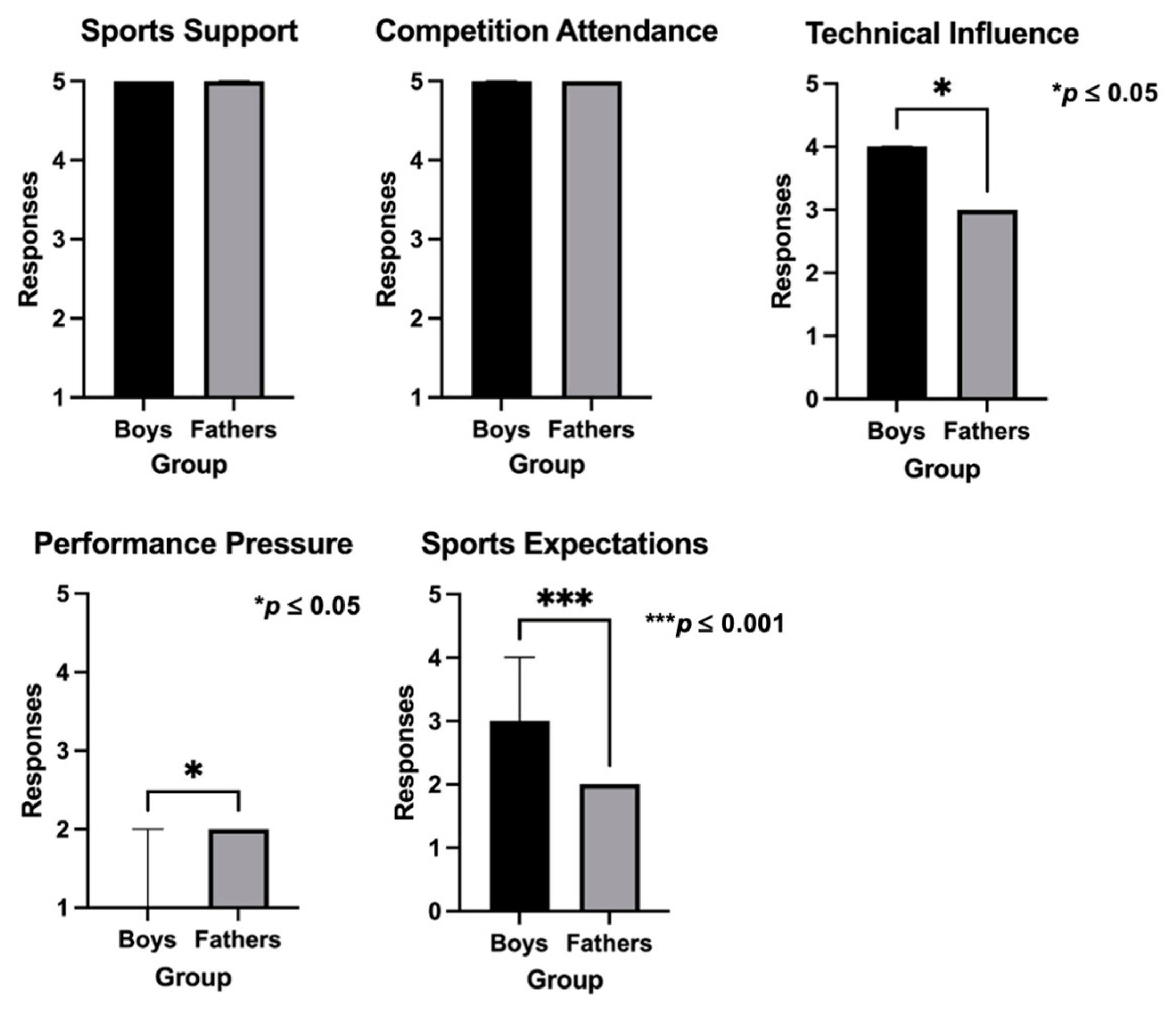

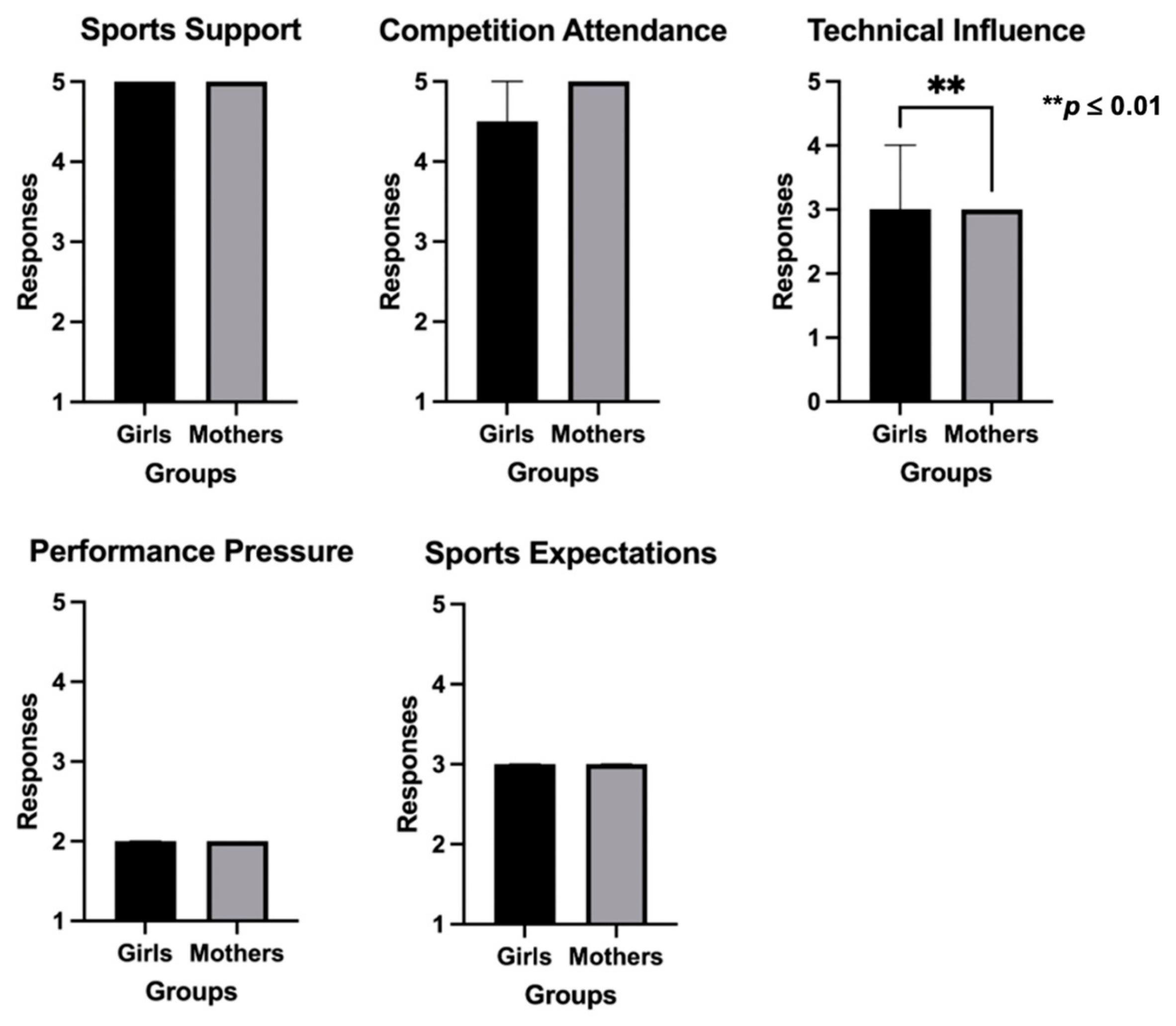

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knight, C.J. Revealing findings in youth sport parenting research. Kinesiol. Rev. 2019, 8, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Holt, N.L. Parenting in youth tennis: Understanding and enhancing children’s experiences. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.E.; Holt, N.L. Talent development in elite junior tennis: Perceptions of players, parents, and coaches. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2005, 17, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, J.E.; Lalanne, J.; Delforge, C. The influence of parenting practices and parental presence on children’s and adolescents’ pre-competitive anxiety. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Tamminen, K.A.; Black, D.E.; Mandigo, J.L.; Fox, K.R. Youth sport parenting styles and practices. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G.L.; Raedeke, T.D. Children’s Perceptions of Parent Sport Involvement: It’s Not How Much, But to What Degree That’s. J. Sport Behav. 1999, 22, 591. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, P.J.; Jones, M.V. A qualitative study of sport enjoyment in the sampling years. Sport Psychol. 2007, 21, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, A.L.; Wilson, S.R.; McDonough, M.H. Parent goals and verbal sideline behavior in organized youth sport. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2015, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.; Temple, V. A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A.; Bichman, A.; Moyal, A.; Brenner, S.; Fass, N.; Been, E. No cutting corners: The effect of parental involvement on youth basketball players in Israel. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 607000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerth, S.; Lee, M.J.; Alfermann, D. Parental involvement and athletes’ career in youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, A.L.; Dotterer, A.M. Individual, relationship, and context factors associated with parent support and pressure in organized youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 23, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, D.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; González-Ponce, I.; Pulido-González, J.J.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. Incidence of parental support and pressure on their children’s motivational processes towards sport practice regarding gender. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhart, N.; Nicaise, V. The gap between athletes’ and parents’ perceptions of parental practices: The role of gender. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 63, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.R. Questionário de Comportamentos Parentais no Desporto (QCPD); Escola de Psicologia, Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N.L.; Tamminen, K.A.; Black, D.E.; Sehn, Z.L.; Wall, M.P. Parental involvement in competitive youth sport settings. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 663–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavolontà, V.; Cataldi, S.; Latino, F.; Carvutto, R.; De Candia, M.; Mastrorilli, G.; Messina, G.; Patti, A.; Fischetti, F. The role of parental involvement in youth sport experience: Perceived and desired behavior by male soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.; Sharp, L.-A.; Woods, D.; Paradis, K.F. Advancing a grounded theory of parental support in competitive girls’ golf. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 66, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooky, C.; Begovic, M.; Sabo, D.; Oglesby, C.A.; Snyder, M. Gender and sport participation in Montenegro. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2016, 51, 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, J.E.; Heinze, K.L.; Davis, M.M.; Butchart, A.T.; Singer, D.C.; Clark, S.J. Gender role beliefs and parents’ support for athletic participation. Youth Soc. 2017, 49, 634–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalabaev, A.; Sarrazin, P.; Fontayne, P.; Boiché, J.; Clément-Guillotin, C. The influence of sex stereotypes and gender roles on participation and performance in sport and exercise: Review and future directions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, S.L. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol. Rev. 1981, 88, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkes, M.L.; Weiss, M.R. Parental influence on children’s cognitive and affective responses to competitive soccer participation. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1999, 11, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, E.; Jermaina, N.; Hambali, B.; Amirudin, A.; Cahyani, F.I.; Dermawan, A.; Ningrum, D.T.M. Sports participation, family communication and positive youth development. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 2024, 12, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omli, J.; Wiese-Bjornstal, D.M. Kids speak: Preferred parental behavior at youth sport events. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Boden, C.M.; Holt, N.L. Junior tennis players’ preferences for parental behaviors. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2010, 22, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Leo, F.M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Amado, D.; García-Calvo, T. The importance of parents’ behavior in their children’s enjoyment and amotivation in sports. J. Hum. Kinet. 2013, 36, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.; Cardoso, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Noite, J.; Lopes, H.; Fernando, C.; Prudente, J. The athlete’s perception of parents behaviors in sport context: A study in youth handball players of the Madeira Handball Association. In Proceedings of the International Seminar of Physical Education, Leisure and Health, Castelo Branco, Portugal, 17–19 June 2019; p. 1481. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sports support (4 items) | 1, 8, 12, 17 Total score = 1–5 | Parental support, satisfaction, and interest in their child’s sports activity. |

| 2. Competition attendance (3 items) | 2, 7, 13 Total score = 1–5 | Parents’ presence at their child’s competitions. |

| 3. Technical influence (4 items) | 3, 6, 11, 16 Total score = 1–5 | Tendency of parents to provide advice or suggestions on how their child can improve technical skills and how they should train and/or compete. |

| 4. Performance pressure (4 items) | 4, 9, 14, 18 Total score = 1–5 | Negative parental behaviors towards poor performance in competitions and unfavorable sports results of their child. |

| 5. Sports expectations (3 items) | 5, 10, 15 Total score = 1–5 | Parents’ positive expectations about their child’s sports future. |

| Total items = 18 |

| D1. | D2. | D3. | D4. | D5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1. | - | 0.326 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.008 | 0.173 ** |

| D2. | - | 0.241 ** | 0.049 | 0.096 * | |

| D3. | - | 0.351 ** | 0.367 ** | ||

| D4. | - | 0.250 ** | |||

| D5. | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopes, M.V.; Ihle, A.; Gouveia, É.R.; Marques, A.; França, C. Analyzing Parental Involvement in Youth Basketball. Sports 2024, 12, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12120350

Lopes MV, Ihle A, Gouveia ÉR, Marques A, França C. Analyzing Parental Involvement in Youth Basketball. Sports. 2024; 12(12):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12120350

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Maria V., Andreas Ihle, Élvio Rúbio Gouveia, Adilson Marques, and Cíntia França. 2024. "Analyzing Parental Involvement in Youth Basketball" Sports 12, no. 12: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12120350

APA StyleLopes, M. V., Ihle, A., Gouveia, É. R., Marques, A., & França, C. (2024). Analyzing Parental Involvement in Youth Basketball. Sports, 12(12), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports12120350