Transmission Success of Entomopathogenic Nematodes Used in Pest Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

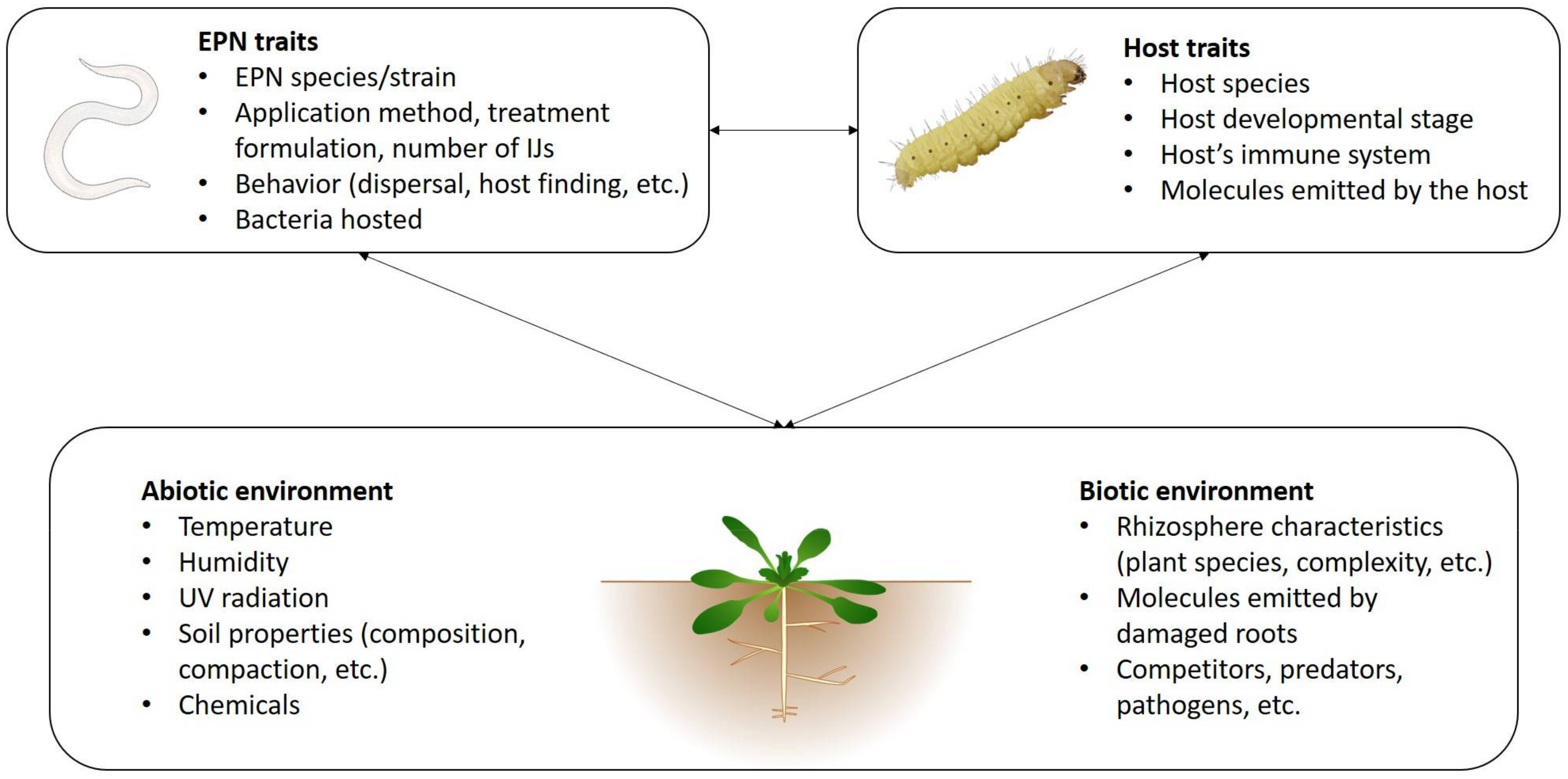

2. Trait Diversity

3. Dispersal and Host Finding

4. Infection

5. Interaction with the Biotic and Abiotic Environment

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poinar, G.O. Nematodes for Biological Control of Insects; CRC Press, Inc.: Boca Raton, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst, R.J. Antibiotic activity of Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with insect pathogenic nematodes of the families Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1982, 128, 3061–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, H.B. Entomopathogenic bacteria as a source of secondary metabolites. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009, 13, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, L.A.; Grzywacz, D.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Frutos, R.; Brownbridge, M.; Goettel, M.S. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Back to the future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Herrera, R. Nematode Pathogenesis of Insects and Other Pests; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-18265-0. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, P.S.; Ehlers, R.U.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I. Nematodes as Biocontrol Agents; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, R.R. Entomopathogenic Nematology; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Laznik, Ž.; Trdan, S. Entomopathogenic nematodes (Nematoda: Rhabditida) in Slovenia: From tabula rasa to implementation into crop production systems. In Insecticides—Advances in Integrated Pest Management; Perveen, F., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 627–656. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, L.G.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Hazir, S.; Jackson, M.A. Effect of inoculum age and physical parameters on in vitro culture of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema feltiae. J. Helminthol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, A.M.; Shields, E.J. Low labor “in vivo” mass rearing method for entomopathogenic nematodes. Biol. Control 2017, 106, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jaffuel, G.; Turlings, T.C.J. Enhanced alginate capsule properties as a formulation of entomopathogenic nematodes. BioControl 2015, 60, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yan, X.; Han, R. Adapted formulations for entomopathogenic nematodes, Steinernema and Heterorhabditis spp. Nematology 2017, 19, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Martínez, C.I.; Lewis, E.E.; Ruiz-Vega, J.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, G.A. Mechanical production of pellets for the application of entomopathogenic nematodes: Effect of pre-acclimation of Steinernema glaseri on its survival time and infectivity against Phyllophaga vetula. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagimu, N.; Ferreira, T.; Malan, A.P. The attributes of survival in the formulation of entomopathogenic nematodes utilised as insect biocontrol agents. Afr. Entomol. 2017, 25, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Martínez, H.; Ruiz-Vega, J.; Matadamas-Ortíz, P.T.; Cortés-Martínez, C.I.; Rosas-Diaz, J. Formulation of entomopathogenic nematodes for crop pest control—A review. Plant Prot. Sci. 2017, 53, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.Y.; Xu, H.; Fu, Y.Q.; Wang, X.Y.; Shen, G.S.; Ma, H.K.; Feng, X.; Pan, J.; Gu, X.S.; Guo, Y.Z.; Ruan, W.B.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I. A comparison of novel entomopathogenic nematode application methods for control of the chive gnat, Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 2006–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Cottrell, T.E.; Mizell, R.F.; Horton, D.L. Curative control of the peachtree borer using entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Nematol. 2016, 48, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Cottrell, T.E.; Mizell, R.F.; Horton, D.L.; Zaid, A. Field suppression of the peachtree borer, Synanthedon exitiosa, using Steinernema carpocapsae: Effects of irrigation, a sprayable gel and application method. Biol. Control 2015, 82, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumus, A.; Karagoz, M.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.; Hazir, S. A novel approach to biocontrol: Release of live insect hosts pre-infected with entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 130, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Sepulveda, C.; Dillman, A.R. Infective juveniles of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema scapterisci are preferentially activated by cricket tissue. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, N.; Karimi, J.; Hosseini, M.; Goldani, M.; Campos-Herrera, R. Pathogenicity of two species of entomopathogenic nematodes against the greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), in laboratory and greenhouse experiments. J. Nematol. 2015, 47, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azarnia, S.; Abbasipour, H.; Saeedizadeh, A.; Askarianzadeh, A. Laboratory assay of entomopathogenic nematodes against clearwing moth (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) larvae. J. Entomol. Sci. 2018, 53, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepenekci, İ.; Hazir, S.; Özdem, A. Evaluation of native entomopathogenic nematodes for the control of the European cherry fruit fly Rhagoletis cerasi L. (Diptera: Tephritidae) larvae in soil. Turkish J. Agric. For. 2015, 39, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.; Ahmad, J.N.; Sharif, M.Z.; Majeed, D.; Kiran, H.; Jafir, M.; Ali, H. Comparative effectiveness of entomopathogenic nematodes against red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) in Pakistan. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. JEZS 2017, 5, 756–760. [Google Scholar]

- Odendaal, D.; Addison, M.F.; Malan, A.P. Entomopathogenic nematodes for the control of the codling moth (Cydia pomonella L.) in field and laboratory trials. J. Helminthol. 2016, 90, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odendaal, D.; Addison, M.F.; Malan, A.P. Control of diapausing codling moth, Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) in wooden fruit bins, using entomopathogenic nematodes (Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laznik, Ž.; Tóth, T.; Lakatos, T.; Vidrih, M.; Trdan, S. The activity of three new strains of Steinernema feltiae against adults of Sitophilus oryzae under laboratory conditions. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Godjo, A.; Zadji, L.; Decraemer, W.; Willems, A.; Afouda, L. Pathogenicity of indigenous entomopathogenic nematodes from Benin against mango fruit fly (Bactrocera dorsalis) under laboratory conditions. Biol. Control 2018, 117, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Waweru, B.; Qiu, X.; Hategekimana, A.; Kajuga, J.; Li, H.; Edgington, S.; Umulisa, C.; Han, R.; Toepfer, S. New entomopathogenic nematodes from semi-natural and small-holder farming habitats of Rwanda. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 820–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, C.; Erbaş, Z.; Yilmaz, H.; Demirbağ, Z.; Demir, İ. A new entomopathogenic nematode species from Turkey, Steinernema websteri (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae), and its virulence. Turkish J. Biol. 2015, 39, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; van Reenen, C.A.; Endo, A.; Tailliez, P.; Pagès, S.; Spröer, C.; Malan, A.P.; Dicks, L.M.T. Photorhabdus heterorhabditis sp. nov., a symbiont of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis zealandica. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, C.T. Perspectives on the behavior of entomopathogenic nematodes from dispersal to reproduction: Traits contributing to nematode fitness and biocontrol efficacy. J. Nematol. 2012, 44, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, B.J.; Fodor, A.; Koppenhöfer, H.S.; Stackebrandt, E.; Patricia Stock, S.; Klein, M.G. Biodiversity and systematics of nematode-bacterium entomopathogens. Biol. Control 2006, 37, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, W.; Lis, M.; Skrzypek, T.; Kreft, A. Comparison of the methods applicable for the pathogenicity assessment of entomopathogenic nematodes. BioControl 2018, 63, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, A.M.D.; Asaiyah, M.A.M.; Brophy, C.; Griffin, C.T. An entomopathogenic nematode extends its niche by associating with different symbionts. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 73, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Stuart, R.J.; McCoy, C.W. Targeted improvement of Steinernema carpocapsae for control of the pecan weevil, Curculio caryae (Horn) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) through hybridization and bacterial transfer. Biol. Control 2005, 34, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murfin, K.E.; Lee, M.M.; Klassen, J.L.; McDonald, B.R.; Larget, B.; Forst, S.; Stock, S.P.; Currie, C.R.; Goodrich-Blair, H. Xenorhabdus bovienii strain diversity impacts coevolution and symbiotic maintenance with Steinernema spp. nematode hosts. mBio 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.J.; Wilson, D.J.; Rodgers, A.; Gerard, P.J. Developing a strategy for using entomopathogenic nematodes to control the African black beetle (Heteronychus arator) in New Zealand pastures and investigating temperature constraints. Biol. Control 2016, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memari, Z.; Karimi, J.; Kamali, S.; Goldansaz, S.H.; Hosseini, M. Are entomopathogenic nematodes effective biological control agents against the carob moth, Ectomyelois ceratoniae? J. Nematol. 2016, 48, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Han, R.; Dolinksi, C. Entomopathogenic nematode production and application technology. J. Nematol. 2012, 44, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smits, P.H. Post-application persistence of entomopathogenic nematodes. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 1996, 6, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Hazir, S.; Lete, L. Viability and virulence of entomopathogenic nematodes exposed to ultraviolet radiation. J. Nematol. 2015, 47, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Brown, I.; Lewis, E.E. Freezing and desiccation tolerance in entomopathogenic nematodes: Diversity and correlation of traits. J. Nematol. 2014, 46, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ulu, T.C.; Susurluk, I.A. Heat and desiccation tolerances of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora strains and relationships between their tolerances and some bioecological characteristics. Invertebr. Surviv. J. 2014, 11, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Menti, H.; Wright, D.J.; Perry, R.N. Desiccation survival of populations of the entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis megidis from Greece and the UK. J. Helminthol. 1997, 71, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.N.; Perry, R.N.; Wright, D.J. Desiccation survival and water contents of entomopathogenic nematodes, Steinernema spp. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae). Int. J. Parasitol. 1997, 27, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggott, S.J.; Liu, Q.Z.; Glazer, I.; Wright, D.J. Does osmoregulatory behaviour in entomopathogenic nematodes predispose desiccation tolerance? Nematology 2002, 4, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimey, H.; Zadji, L.; Afouda, L.; Moens, M.; Decraemer, W. Influence of pesticides, soil temperature and moisture on entomopathogenic nematodes from southern Benin and control of underground termite nest populations. Nematology 2015, 17, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, E.A.; Nielsen, U.N.; Johnson, S.N.; Riegler, M. Susceptibility of Queensland fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni (Froggatt) (Diptera: Tephritidae), to entomopathogenic nematodes. Biol. Control 2014, 69, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, C.C.; Willett, D.S.; Junior, A.M.; Pareja, M.; El-Borai, F.E.; Dickson, D.W.; Stelinski, L.L.; Duncan, L.W.; Moino, A.; Pareja, M.; et al. Stimulation of the salicylic acid pathway aboveground recruits entomopathogenic nematodes belowground. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme, V.M.; Beck, B.K.; Berckmoes, E.; Moerkens, R.; Wittemans, L.; De Vis, R.; Nuyttens, D.; Casteels, H.F.; Maes, M.; Tirry, L.; et al. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes against larvae of Tuta absoluta in the laboratory. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 1702–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portman, S.L.; Krishnankutty, S.M.; Reddy, G.V.P. Entomopathogenic nematodes combined with adjuvants presents a new potential biological control method for managing the wheat stem sawfly, Cephus cinctus (Hymenoptera: Cephidae). PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dito, D.F.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Dunlap, C.A.; Behle, R.W.; Lewis, E.E. Enhanced biological control potential of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema carpocapsae, applied with a protective gel formulation. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.M.; Matthews, G.A.; Wright, D.J. Screening and selection of adjuvants for the spray application of entomopathogenic nematodes against a foliar pest. Crop Prot. 1998, 17, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.J.; Peters, A.; Schroer, S.; Fife, J.P. Application technology. In Nematodes as Biocontrol Agents; Grewal, P., Ehlers, R.-U., Shapiro-Ilan, D.I., Eds.; CABI: Wikiwand, UK, 2005; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Noosidum, A.; Satwong, P.; Chandrapatya, A.; Lewis, E.E. Efficacy of Steinernema spp. plus anti-desiccants to control two serious foliage pests of vegetable crops, Spodoptera litura F. and Plutella xylostella L. Biol. Control 2016, 97, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.I.; Glazer, I. Comparison of entomopathogenic nematode infectivity from infected hosts versus aqueous suspension. Environ. Entomol. 1996, 25, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, F.; Alborn, H.T.; von Reuss, S.H.; Ajredini, R.; Ali, J.G.; Akyazi, F.; Stelinski, L.L.; Edison, A.S.; Schroeder, F.C.; Teal, P.E. Interspecific nematode signals regulate dispersal behavior. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiltpold, I.; Hibbard, B.E.; French, B.W.; Turlings, T.C.J. Capsules containing entomopathogenic nematodes as a Trojan horse approach to control the western corn rootworm. Plant Soil 2012, 358, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salame, L.; Glazer, I. Stress avoidance: Vertical movement of entomopathogenic nematodes in response to soil moisture gradient. Phytoparasitica 2015, 43, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Borai, F.; Killiny, N.; Duncan, L.W. Concilience in entomopathogenic nematode responses to water potential and their geospatial patterns in Florida. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.P.; Malan, A.P.; Terblanche, J.S. Divergent thermal specialisation of two South African entomopathogenic nematodes. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, S.; Karimi, J.; Koppenhöfer, A.M. New insight into the management of the tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) with entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Youngman, R.R.; Kok, L.T.; Laub, C.A.; Pfeiffer, D.G. Interaction between entomopathogenic nematodes and entomopathogenic fungi applied to third instar southern masked chafer white grubs, Cyclocephala lurida (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae), under laboratory and greenhouse conditions. Biol. Control 2014, 76, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, A.; Gaffney, M.; Kapranas, A.; Griffin, C.T. Conditioning the entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema carpocapsae and Heterorhabditis megidis by pre-application storage improves efficacy against black vine weevil, Otiorhynchus sulcatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) at low and moderate temperatures. Biol. Control 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajuga, J.; Hategekimana, A.; Yan, X.; Waweru, B.W.; Li, H.; Li, K.; Yin, J.; Cao, L.; Karanja, D.; Umulisa, C.; et al. Management of white grubs (Coleoptera: Scarabeidae) with entomopathogenic nematodes in Rwanda. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Karagoz, M.; Hazir, S.; Kaya, H.K. Evaluation of entomopathogenic nematodes and their combined application against Curculio elephas and Polyphylla fullo larvae. J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yan, X.; Zhao, G.; Chen, J.; Han, R. Efficacy of entomopathogenic Steinernema and Heterorhabditis nematodes against Holotrichia oblita. J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapranas, A.; Malone, B.; Quinn, S.; Mc Namara, L.; Williams, C.D.; O’Tuama, P.; Peters, A.; Griffin, C.T.; O’Tuama, P.; Peters, A.; et al. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes for control of large pine weevil, Hylobius abietis: Effects of soil type, pest density and spatial distribution. Pest Sci. 2016, 90, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, F.B.; Reddy, G.V.P. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes and sprayable polymer gel against crucifer flea beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on canola. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1706–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, A.; Sáenz-Aponte, A. Susceptibility variation to different entomopathogenic nematodes in Strategus aloeus L (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Springerplus 2015, 4, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, D.D.O.; Gomes, V.M.; Dolinski, C.; Souza, R.M. Potential of entomopathogenic nematodes as biocontrol agents of immature stages of Aedes aegypti. Nematoda 2015, 2, e092015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Gong, Q.; Fan, K.; Sun, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, K. Synergistic effect of entomopathogenic nematodes and thiamethoxam in controlling Bradysia odoriphaga Yang and Zhang (Diptera: Sciaridae). Biol. Control 2017, 111, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, C.V.; Wilding, C.S.; Rae, R. Susceptibility of Chironomus plumosus larvae (Diptera: Chironomidae) to entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditidae: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae): Potential for control. Eur. J. Entomol. 2017, 114, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Audsley, N. Further screening of entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes as control agents for Drosophila suzukii. Insects 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garriga, A.; Morton, A.; Garcia-del-Pino, F. Is Drosophila suzukii as susceptible to entomopathogenic nematodes as Drosophila melanogaster? J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Englert, C.; Herz, A. Effect of entomopathogenic nematodes on different developmental stages of Drosophila suzukii in and outside fruits. BioControl 2017, 62, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archana, M.; D’Souza, P.E.; Patil, J. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) on developmental stages of house fly, Musca domestica. J. Parasit. Dis. 2017, 41, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Rodrigues Leal, L.C.; de Oliveira Monteiro, C.M.; de Mendonca, A.E.; Bittencourt, V.R.E.P.; Bittencourt, A.J.; Rodrigues, L.C.; de Oliveira, C.; de Mendonca, A.E.; Pinheiro, V.R.; Bittencourt, A.J. Potential of entomopathogenic nematodes of the genus Heterorhabditis for the control of Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae). Brazilian J. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 26, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkvens, N.; Van Vaerenbergh, J.; Maes, M.; Beliën, T.; Viaene, N. Entomopathogenic nematodes fail to parasitize the woolly apple aphid Eriosoma lanigerum as their symbiotic bacteria are suppressed. J. Appl. Entomol. 2014, 138, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vieux, P.D.; Malan, A.P. An overview of the vine mealybug (Planococcus ficus) in South African vineyards and the use of entomopathgenic nematodes as potential biocontrol agent. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 34, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wagutu, G.K.; Kang’ethe, L.N.; Waturu, C.N. Efficacy of entomopathogenic nematode (Steinernema karii) in control of termites (Coptorermes formosanus). J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2017, 18, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zadji, L.; Baimey, H.; Afouda, L.; Moens, M.; Decraemer, W. Comparative susceptibility of Macrotermes bellicosus and Trinervitermes occidentalis (Isoptera: Termitidae) to entomopathogenic nematodes from Benin. Nematology 2014, 16, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, D.; Addison, M.F.; Malan, A.P. Evaluation of above-ground application of entomopathogenic nematodes for the control of diapausing codling moth (Cydia pomonella L.) under natural conditions. Afr. Entomol. 2016, 24, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rodríguez, O.; Campbell, J.F.; Ramaswamy, S.B. Pathogenicity of three species of entomopathogenic nematodes to some major stored-product insect pests. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2006, 42, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, T.A.; Gutiérrez, G.A.M.; Tinoco, C.E.; Cortés-martínez, C.I.; Sánchez, D.M. Loss caused by fruit worm and its treatment with entomopathogenic nematodes in fruits of Physalis ixocarpa Guenee. Int. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Res. 2016, 4, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sunanda, B.S.; Jeyakumar, P.; Jacob, V. V Bioefficacy of different formulations of entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae against Diamond back moth (Plutella xylostella) infesting Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). J. Biopestic. 2014, 7, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Safdar, H.; Javed, N.; Khan, S.A.; Arshad, M. Reproduction potential of entomopathogenic nematodes on armyworm (Spodoptera litura). Pak. J. Zool. 2018, 50, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabörklü, S.; Ayvaz, A.; Yilmaz, S.; Azizoglu, U.; Akbulut, M. Native entomopathogenic nematodes isolated from Turkey and their effectiveness on pine processionary moth, Thaumetopoea wilkinsoni Tams. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2015, 61, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, E.; Karimi, J.; Sadeghi-Nameghi, H.; Hosseini, M. Efficacy of two entomopathogenic nematodes Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and Steinernema carpocapsae for control of the leopard moth borer Zeuzera pyrina (Lepidoptera: Cossidae) larvae under laboratory conditions. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, A.P.; Knoetze, R.; Tiedt, L. Heterorhabditis noenieputensis n. sp. (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae), a new entomopathogenic nematode from South Africa. J. Helminthol. 2014, 88, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahina, F.; Tabassum, K.A.; Salma, J.; Mehreen, G.; Knoetze, R. Heterorhabditis pakistanense n. sp. (Nematoda: Heterorhabditidae) a new entomopathogenic nematode from Pakistan. J. Helminthol. 2017, 91, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyaz, S.; Khanum, T.A.; Ali, S.; Solangi, G.S.; Gulsher, M.; Javed, S. Steinernema balochiense n. sp. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) a new entomopathogenic nematode from Pakistan. Zootaxa 2015, 3904, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çimen, H.; Půža, V.; Nermuť, J.; Hatting, J.; Ramakuwela, T.; Faktorová, L.; Hazir, S. Steinernema beitlechemi n. sp., a new entomopathogenic nematode (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from South Africa. Nematology 2016, 18, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çimen, H.; Puza, V.; Nermut, J.; Hatting, J.; Ramakuwela, T.; Hazir, S. Steinernema biddulphi n. sp., a new entomopathogenic nematode (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from South Africa. J. Nematol. 2016, 48, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çimen, H.; Lee, M.M.; Hatting, J.; Hazir, S.; Stock, S.P. Steinernema innovationi n. sp. (Panagrolaimomorpha: Steinernematidae), a new entomopathogenic nematode species from South Africa. J. Helminthol. 2015, 89, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mráček, Z.; Nermuť, J. Steinernema poinari sp. n. (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) a new entomopathogenic nematode from the Czech Republic. Zootaxa 2014, 3760, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Půža, V.; Nermut, J.; Mráček, Z.; Gengler, S.; Haukeland, S. Steinernema pwaniensis n. sp., a new entomopathogenic nematode (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from Tanzania. J. Helminthol. 2017, 91, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgadze, O.; Lortkhipanidze, M.; Ogier, J.-C.; Tailliez, P.; Burjanadze, M. Steinernema tbilisiensis sp. n. (Nematoda: Steinernematidae)—A new species of entomopathogenic nematode from Georgia. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. A 2015, 5, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, S.P. Steinernema tophus sp. n. (Nematoda: Steinernematidae), a new entomopathogenic nematode from South Africa. Zootaxa 2014, 3821, 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Gaugler, R. Production technology for entomopathogenic nematodes and their bacterial symbionts. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 28, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumaya, N.H.; Gohil, R.; Okolo, C.; Addis, T.; Doerfler, V.; Ehlers, R.U.; Molina, C. Applying inbreeding, hybridization and mutagenesis to improve oxidative stress tolerance and longevity of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2018, 181, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ow, M.C.; Borziak, K.; Nichitean, A.M.; Dorus, S.; Hall, S.E. Early experiences mediate distinct adult gene expression and reproductive programs in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, P.S.; Peters, A. Formulation and quality. In Nematodes as Biocontrol Agents; Grewal, P.S., Ehlers, R.U., Shapiro-Ilan, D.I., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M.N.; Stolinski, M.; Wright, D.J. Neutral lipids and the assessment of infectivity in entomopathogenic nematodes: Observations on four Steinernema species. Parasitology 1997, 114, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.N.; Wright, D.J. Glycogen: Its importance in the infectivity of aged juveniles of Steinernema carpocapsae. Parasitology 1997, 114, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menti, H.; Wright, D.J.; Perry, R.N. Infectivity of populations of the entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis megidis in relation to temperature, age and lipid content. Nematology 2000, 2, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.E.; Campbell, J.; Griffin, C.; Kaya, H.; Peters, A. Behavioral ecology of entomopathogenic nematodes. Biol. Control 2006, 38, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C.T. Behaviour and population dynamics of entomopathogenic nematodes following application. In Nematode Pathogenesis of Insects and Other Pests: Ecology and Applied Technologies for Sustainable Plant and Crop Protection; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 57–95. ISBN 9783319182667. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, A.R.; Guillermin, M.L.; Ha, J.; Kim, B.; Sternberg, P.W.; Hallem, E.A. Olfaction shapes host—Parasite interactions in parasitic nematodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2324–E2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torr, P.; Heritage, S.; Wilson, M.J. Vibrations as a novel signal for host location by parasitic nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burman, M.; Pye, A.E. Neoaplectana carpocapsae: Movements of nematode populations on a thermal gradient. Exp. Parasitol. 1980, 49, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, J.A.; Poinar, G.O. Location of insect hosts by the nematode, Neoaplectana carpocapsae, in response to temperature. Behaviour 1982, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.F.; Gaugler, R. Nictation behaviour and its ecological implications in the host search strategies of entomopathogenic nematodes (Hererorhabditidae and Steinernematidae). Behaviour 1993, 126, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.F.; Kaya, H.K. How and why a parasitic nematode jumps. Nature 1999, 397, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.F.; Kaya, H.K. Variation in entomopathogenic nematode (Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) infective-stage jumping behaviour. Nematology 2002, 4, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, H.K.; Grewal, P.S. Lateral dispersal and foraging behavior of entomopathogenic nematodes in the absence and presence of mobile and non-mobile hosts. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, H.K.; Taylor, R.A.J.; Grewal, P.S. Ambush foraging entomopathogenic nematodes employ “sprinters” for long-distance dispersal in the absence of hosts. J. Parasitol. 2014, 100, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, H.K.; Michel, A.P.; Grewal, P.S. Genetic selection of the ambush foraging entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema carpocapsae for enhanced dispersal and its associated trade-offs. Evol. Ecol. 2014, 28, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapranas, A.; Malone, B.; Quinn, S.; O’Tuama, P.; Peters, A.; Griffin, C.T.; Tuama, P.O.; Peters, A.; Griffin, C.T. Optimizing the application method of entomopathogenic nematode suspension for biological control of large pine weevil Hylobius abietis. BioControl 2017, 62, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, H.K.; Acosta, N.; Cheng, Z.; Grewal, P.S.; Hoy, C.W. Effect of habitat and soil management on dispersal and distribution patterns of entomopathogenic nematodes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 121, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapranas, A.; Maher, A.M.D.; Griffin, C.T. The influence of organic matter content and media compaction on the dispersal of entomopathogenic nematodes with different foraging strategies. Parasitology 2017, 144, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffuel, G.; Blanco-Pérez, R.; Büchi, L.; Mäder, P.; Fließbach, A.; Charles, R.; Degen, T.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Campos-Herrera, R. Effects of cover crops on the overwintering success of entomopathogenic nematodes and their antagonists. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 114, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, B.A.; Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J.; Malan, A.P.; Hurley, B.P. Diversity of entomopathogenic nematodes and their symbiotic bacteria in south African plantations and indigenous forests. Nematology 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Mertz, N.; Agudelo, E.J.G.; Sales, F.S.; Rohde, C.; Moino, A. Phoretic dispersal of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis amazonensis by the beetle Calosoma granulatum. Phytoparasitica 2014, 42, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Borai, F.E.; Campos-Herrera, R.; Stuart, R.J.; Duncan, L.W. Substrate modulation, group effects and the behavioral responses of entomopathogenic nematodes to nematophagous fungi. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2011, 106, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Lewis, E.E.; Schliekelman, P. Aggregative group behavior in insect parasitic nematode dispersal. Int. J. Parasitol. 2014, 44, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, W.B.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.; Lewis, E.E.; Kaplan, F.; Alborn, H.; Gu, X.H.; Schliekelman, P. Movement patterns in entomopathogenic nematodes: Continuous vs. temporal. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2018, 151, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallem, E.A.; Dillman, A.R.; Hong, A.V.; Zhang, Y.; Yano, J.M.; Demarco, S.F.; Sternberg, P.W. A sensory code for host seeking in parasitic nematodes. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, M.J.; Martini, X.; Khrimian, A.; Stelinski, L. A weevil sex pheromone serves as an attractant for its entomopathogenic nematode predators. Chemoecology 2017, 27, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmann, S.; Köllner, T.G.; Degenhardt, J.; Hiltpold, I.; Toepfer, S.; Kuhlmann, U.; Gershenzon, J.; Turlings, T.C.J. Recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes by insect-damaged maize roots. Nature 2005, 434, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Hiltpold, I.; Rasmann, S. The importance of root-produced volatiles as foraging cues for entomopathogenic nematodes. Plant Soil 2012, 358, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laznik, Ž.; Trdan, S. Attraction behaviors of entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) to synthetic volatiles emitted by insect damaged potato tubers. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 42, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Vieux, P.D.; Malan, A.P. Prospects for using entomopathogenic nematodes to control the vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus, in South African vineyards. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 36, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Peñaflor, M.F.G.V.; Leite, L.G.; Silva, W.D.; Martins, F.; Bento, J.M.S. Attraction of entomopathogenic nematodes to sugarcane root volatiles under herbivory by a sap-sucking insect. Chemoecology 2016, 26, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hua, C.; Wang, C. Three dimensional study of wounded plant roots recruiting entomopathogenic nematodes with Pluronic gel as a medium. Biol. Control 2015, 89, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, D.E.; Dillon, A.B.; Griffin, C.T. Simulated roots and host feeding enhance infection of subterranean insects by the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarta, L.; Hibbard, B.E.; Bohn, M.O.; Hiltpold, I. The role of root architecture in foraging behavior of entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 122, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiriboga, M.X.; Campos-Herrera, R.; Jaffuel, G.; Röder, G.; Turlings, T.C.J. Diffusion of the maize root signal (E)-β-caryophyllene in soils of different textures and the effects on the migration of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis megidis. Rhizosphere 2017, 3, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, C.C.; Willett, D.S.; Pereira, R.V.; de Sabino, P.H.S.; Junior, A.M.; Pareja, M.; Dickson, D.W. Parameters affecting plant defense pathway mediated recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, D.S.; Alborn, H.T.; Duncan, L.W.; Stelinski, L.L. Social Networks of Educated Nematodes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.D.; Dillon, A.B.; Ennis, D.E.; Hennessy, R.; Griffin, C.T. Differential susceptibility of pine weevil, Hylobius abietis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), larvae and pupae to entomopathogenic nematodes and death of adults infected as pupae. BioControl 2015, 60, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pérez, R.; Bueno-Pallero, F.Á.; Neto, L.; Campos-Herrera, R. Reproductive efficiency of entomopathogenic nematodes as scavengers. Are they able to fight for insect’s cadavers? J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftherianos, I.; Shokal, U.; Yadav, S.; Kenney, E.; Maldonado, T. Insect immunity to entomopathogenic nematodes and their mutualistic bacteria. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017, 402, 123–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Gao, A.; Li, B.; Wang, M.; Shan, L. Two symbiotic bacteria of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis spp. against Galleria mellonella. Toxicon 2017, 127, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, J.M.; Carrillo, M.A.; Hallem, E.A. Variation in the susceptibility of Drosophila to different entomopathogenic nematodes. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Macchietto, M.; Chang, D.; Barros, M.M.; Baldwin, J.; Mortazavi, A.; Dillman, A.R. Activated entomopathogenic nematode infective juveniles release lethal venom proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisch, G.; Pagès, S.; McMullen, J.G.; Stock, S.P.; Duvic, B.; Givaudan, A.; Gaudriault, S. Xenorhabdus bovienii CS03, the bacterial symbiont of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema weiseri, is a non-virulent strain against lepidopteran insects. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 124, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, J.G.; Peterson, B.F.; Forst, S.; Blair, H.G.; Stock, S.P. Fitness costs of symbiont switching using entomopathogenic nematodes as a model. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Y.; Cowles, R.S.; Cowles, E.A.; Gaugler, R.; Cox-Foster, D.L. Relationship between the successful infection by entomopathogenic nematodes and the host immune response. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007, 37, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvandi, J.; Karimi, J.; Dunphy, G.B. Cellular reactions of the white grub larvae, Polyphylla adspersa, against entomopathogenic nematodes. Nematology 2014, 16, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahatkhah, Z.; Karimi, J.; Ghadamyari, M.; Brivio, M.F. Immune defenses of Agriotes lineatus larvae against entomopathogenic nematodes. BioControl 2015, 60, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalitha, K.; Karthi, S.; Vengateswari, G.; Karthikraja, R.; Perumal, P.; Shivakumar, M.S. Effect of entomopathogenic nematode of Heterorhabditis indica infection on immune and antioxidant system in lepidopteran pest Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Parasit. Dis. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.A.M.; Taha, M.A.; Salem, H.H.A. Changes in enzyme activities in Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera, noctuidae) as a response to entomopathogenic nematode infection. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, L.; Shiri, M.; Dunphy, G.B. Effect of entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema feltiae, on survival and plasma phenoloxidase activity of Helicoverpa armigera (Hb) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in laboratory conditions. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda-Rossetti, S.; Mastore, M.; Protasoni, M.; Brivio, M.F. Effects of an entomopathogen nematode on the immune response of the insect pest red palm weevil: Focus on the host antimicrobial response. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 133, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, E.; Eleftherianos, I. Entomopathogenic and plant pathogenic nematodes as opposing forces in agriculture. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016, 46, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmberger, M.S.; Shields, E.J.; Wickings, K.G. Ecology of belowground biological control: Entomopathogenic nematode interactions with soil biota. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 121, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.D.; Williams, C.D.; Dillon, A.B.; Griffin, C.T. Inundative pest control: How risky is it? A case study using entomopathogenic nematodes in a forest ecosystem. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 380, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babendreier, D.; Jeanneret, P.; Pilz, C.; Toepfer, S. Non-target effects of insecticides, entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes applied against western corn rootworm larvae in maize. J. Appl. Entomol. 2015, 139, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, H.M.; Sabry, A.K.H.; Gaber, N.M. Biosafety of different entomopathogenic nematodes species on some insects natural enemies. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1878–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Dutka, A.; McNulty, A.; Williamson, S.M. A new threat to bees? Entomopathogenic nematodes used in biological pest control cause rapid mortality in Bombus terrestris. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorter, J.R.; Rueppell, O. A review on self-destructive defense behaviors in social insects. Insectes Soc. 2012, 59, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, Z.; Brown, M.J.F. Bring out your dead: Quantifying corpse removal in Bombus terrestris, an annual eusocial insect. Anim. Behav. 2018, 138, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.D.; Griffin, C.T. Local host-dependent persistence of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae used to control the large pine weevil Hylobius abietis. BioControl 2016, 61, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcu, B.; Hazir, S.; Kaya, H.K. Scavenger deterrent factor (SDF) from symbiotic bacteria of entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 110, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Kaya, H.K.; Heungens, K.; Goodrich-Blair, H. Response of ants to a deterrent factor(s) produced by the symbiotic bacteria of entomopathogenic nematodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6202–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, A.; Magoolagan, L.; Kennedy, Z.; Spencer, K.A. Parasite-induced warning coloration: A novel form of host manipulation. Anim. Behav. 2011, 81, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, R.K.; Aiswarya, D.; Gulcu, B.; Raja, M.; Perumal, P.; Sivaramakrishnan, S.; Kaya, H.K.; Hazir, S. Response of three cyprinid fish species to the Scavenger Deterrent Factor produced by the mutualistic bacteria associated with entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 143, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, N.R.; Agudelo, E.J.G.; Sales, F.S.; Moino Junior, A. Effects of entomopathogenic nematodes on the predator Calosoma granulatum in the laboratory. J. Insect Behav. 2015, 28, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulug, D.; Hazir, S.; Kaya, H.K.; Lewis, E. Natural enemies of natural enemies: The potential top-down impact of predators on entomopathogenic nematode populations. Ecol. Entomol. 2014, 39, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A.B.; Moore, C.P.; Downes, M.J.; Griffin, C.T. Evict or infect? Managing populations of the large pine weevil, Hylobius abietis, using a bottom-up and top-down approach. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 2634–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbata, G.N.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I. Compatibility of Heterorhabditis indica (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) and Habrobracon hebetor (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) for biological control of Plodia interpunctella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Biol. Control 2010, 54, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heve, W.K.; El-Borai, F.E.; Carrillo, D.; Duncan, L.W. Increasing entomopathogenic nematode biodiversity reduces efficacy against the Caribbean fruit fly Anastrepha suspensa: Interaction with the parasitoid Diachasmimorpha longicaudata. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Herrera, R.; Půža, V.; Jaffuel, G.; Blanco-Pérez, R.; Čepulyte-Rakauskiene, R.; Turlings, T.C.J. Unraveling the intraguild competition between Oscheius spp. nematodes and entomopathogenic nematodes: Implications for their natural distribution in Swiss agricultural soils. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Herrera, R.; Jaffuel, G.; Chiriboga, X.; Blanco-Pérez, R.; Fesselet, M.; Půža, V.; Mascher, F.; Turlings, T.C.J. Traditional and molecular detection methods reveal intense interguild competition and other multitrophic interactions associated with native entomopathogenic nematodes in Swiss tillage soils. Plant Soil 2015, 389, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, K.M.; Zenner, A.N.R.L.; Hartley, C.J.; Griffin, C.T. Interference competition in entomopathogenic nematodes: Male Steinernema kill members of their own and other species. Int. J. Parasitol. 2014, 44, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapranas, A.; Maher, A.M.D.; Griffin, C.T. Higher relatedness mitigates mortality in a nematode with lethal male fighting. J. Evol. Biol. 2016, 29, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Javed, N.; Kamran, M.; Abbas, H.; Safdar, A.; Ul Haq, I. Management of Meloidogyne incognita race 1 through the use of entomopathogenic nematodes in tomato. Pak. J. Zool. 2016, 48, 763–768. [Google Scholar]

- Kepenekci, I.; Hazir, S.; Lewis, E.E. Evaluation of entomopathogenic nematodes and the supernatants of the in vitro culture medium of their mutualistic bacteria for the control of the root-knot nematodes Meloidogyne incognita and M. arenaria. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aatif, H.M.; Javed, N.; Khan, S.A.; Ahmed, S.; Raheel, M. Virulence of entomopathogenic nematodes against Meloidogyne incognita for invasion, development and reproduction at different application times in brinjal roots. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2015, 17, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Orellana, D.; Phelan, L.P.; Cañas, L.; Grewal, P.S. Entomopathogenic nematodes induce systemic resistance in tomato against Spodoptera exigua, Bemisia tabaci and Pseudomonas syringae. Biol. Control 2016, 93, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazir, S.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Hazir, C.; Leite, L.G.; Cakmak, I.; Olson, D. Multifaceted effects of host plants on entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 135, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, S.; Olmstead, D.; Tian, J.-C.; Collins, H.L.; Shelton, A.M. Tri-trophic studies using Cry1Ac-resistant Plutella xylostella demonstrate no adverse effects of Cry1Ac on the entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Frazer, J.; Banga, A.; Pruitt, K.; Harsh, S.; Jaenike, J.; Eleftherianos, I. Endosymbiont-based immunity in Drosophila melanogaster against parasitic nematode infection. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Daugherty, S.; Shetty, A.C.; Eleftherianos, I. RNAseq analysis of the drosophila response to the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2017, 7, 1955–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadnal, J.; Ratnappan, R.; Keaney, M.; Kenney, E.; Eleftherianos, I.; O’Halloran, D.; Hawdon, J.M. Identification of candidate infection genes from the model entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. BMC Genomics 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arefin, B.; Kucerova, L.; Dobes, P.; Markus, R.; Strnad, H.; Wang, Z.; Hyrsl, P.; Zurovec, M.; Theopold, U. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of Drosophila larvae infected by entomopathogenic nematodes shows involvement of complement, recognition and extracellular matrix proteins. J. Innate Immun. 2014, 6, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Půža, V.; Chundelová, D.; Nermuť, J.; Žurovcová, M.; Mráček, Z. Intra-individual variability of ITS regions in entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae: Nematoda): Implications for their taxonomy. BioControl 2015, 60, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, K.; Karthik, R.R.; Razia, M.; Chellapandi, P.; Sivaramakrishnan, S. Genetic diversity of entomopathogenic nematodes in undisrupted ecosystem revealed with PCR-RAPD markers. Int. J. Nematol. 2014, 24, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mandadi, N.; Hendrickson, C.; Handanahal, S.; Rajappa, T.; Pai, N.; Javeed, S.; Verghese, A.; Rai, A.; Pappu, A.; Nagaraj, G.; et al. Genome sequences of Photorhabdus luminescens strains isolated from entomopathogenic nematodes from southern India. Genomics Data 2015, 6, 46–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado-morales, R.; Rivera-gómez, N.; Beltrán, L.F.L.; Hernández-mendoza, A.; Dantán-Gonzáles, E. Draft genome sequence of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa NA04 bacterium isolated from an entomopathogenic nematode. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00746-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, T.; Afrin, T.; Yoshida, M. Complete mitochondrial genomes of four entomopathogenic nematode species of the genus Steinernema. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, D.; Wood, P.L.; Burk, T.J.; Crawford, B.; Wright, S.M.; Adams, B.J. Evolution of virulence in Photorhabdus spp., entomopathogenic nematode symbionts. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 39, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhi, V.S.; Ment, D.; Salame, L.; Soroker, V.; Glazer, I. Genetic improvement of host-seeking ability in the entomopathogenic nematodes Steinernema carpocapsae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora toward the Red Palm Weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Biol. Control 2016, 100, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Baiocchi, T.; Dillman, A.R. Genomics of entomopathogenic nematodes and implications for pest control. Trends Parasitol. 2016, 32, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pest group | Pest Species | Nematode Species Tested | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coleoptera | Anomala graueri (white grub) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. longicaudum | Kajuga et al., 2018 [66] |

| Curculio elephas (chestnut weevil) | H. bacteriophora, S. glaseri, S. weiseri | Demir et al., 2015 [67] | |

| Holotrichia oblita (white grub) | H. bacteriophora, S. longicaudum | Guo et al., 2015 [68] | |

| Hylobius abietis (large pine weevil) | S. carpocapsae, S. downesi | Kapranas et al., 2016 [69] | |

| Phyllotreta cruciferae (crucifer flea beetle) | H. bacteriophora, H. indica, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Antwi and Reddy 2016 [70] | |

| Polyphylla fullo | H. bacteriophora, S. glaseri, S. weiseri | Demir et al., 2015 [67] | |

| Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (red palm weevil) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Manzoor et al., 2017 [24] | |

| Strategus aloeus (oil palm chiza) | H. bacteriophora, H. indica, S. colombiense, S. feltiae, S. websteri | Gómez and Sáenz-Aponte 2015 [71] | |

| Diptera | Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) | H. baujardi, S. carpocapsae, H. indica, | Cardoso et al., 2015 [72] |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | H. indica, H. tayserae | Godjo et al., 2018 [28] | |

| Bactrocera tryoni (Queensland fruit fly) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Langford et al., 2014 [49] | |

| Bradysia odoriphaga (chive maggot) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, H. indica, S. longicaudum | Bai et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2017 [16,73] | |

| Chironomus plumosus | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. kraussei | Edmunds et al., 2017 [74] | |

| Drosophila suzukii (spotted wing drosophila) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. kraussei | Cuthbertson and Audsley 2016; Hübner et al., 2017; Garriga et al., 2018 [75,76,77] | |

| Musca domestica (housefly) | H. indica, S. abbasi, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. glaseri | Archana et al., 2017 [78] | |

| Rhagoletis cerasi (European cherry fruit fly) | H. bacteriophora, H. marelatus, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Kepenekci et al., 2015 [23] | |

| Stomoxys calcitrans (stable fly) | H. bacteriophora, H. baujardi | Leal et al. 2017 [79] | |

| Hemiptera | Eriosoma lanigerum (wooly apple aphid) | H. bacteriophora, H. megidis, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. glaseri, S. kraussei | Berkvens et al., 2014 [80] |

| Planococcus ficus (vine mealybug) | S. yirgalemense | Le Vieux and Malan 2013 [81] | |

| Trialeurodes vaporariorum (greenhouse whitefly) | H. bacteriophora, S. feltiae | Rezaei et al., 2015 [21] | |

| Hymenoptera | Cephus cinctus (wheat stem sawfly) | H. bacteriophora, H. indica, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. glaseri, S. kraussei, S. riobrave | Portman et al., 2016 [52] |

| Isoptera | Coptotermes formosanus (formosan subterranean termite) | S. karii | Wagutu et al., 2017 [82] |

| Macrotermes bellicosus (termite) | H. indica, H. sonorensi | Zadji et al., 2014 [83] | |

| Trinervitermes occidentalis (termite) | H. indica, H. sonorensi | Zadji et al., 2014 [83] | |

| Lepidoptera | Cydia pomonella (codling moth) | H. bacteriophora, S. feltiae, S. jeffreyense, S. yirgalemense | Odendaal et al., 2016 [25,26,84] |

| Ectomyelois ceratoniae (carob moth) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Memari et al., 2016 [39] | |

| Ephestia kuehniella (mill moth) | S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. riobrave | Ramos-Rodríguez et al., 2006 [85] | |

| Heliothis subflexa | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae, S. websteri | Bolaños et al. 2016 [86] | |

| Paranthrene diaphana (clearwing moth) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Azarnia et al., 2018 [22] | |

| Plodia interpunctella (Indian meal moth) | S. riobrave, S. feltiae, S. carpocapsae | Ramos-Rodríguez et al., 2006 [85] | |

| Plutella xylostella (diamondblack moth) | S. carpocapsae | Sunanda et al., 2014 [87] | |

| Spodoptera litura (tobacco cutworm) | H. bacteriophora, S. glaseri | Safdar et al., 2018 [88] | |

| Synanthedon exitiosa (peachtree borer) | S. carpocapsae | Shapiro-Ilan et al., 2016 [17] | |

| Thaumetopoea wilkinsoni (pine processionary moth) | S. affine, S. feltiae | Karabörklü et al., 2015 [89] | |

| Tuta absoluta (tomato leaf miner) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae, S. feltiae | Van Damme et al., 2016; Kamali et al., 2018 [51,63] | |

| Zeuzera pyrina (leopard moth) | H. bacteriophora, S. carpocapsae | Salari et al., 2015 [90] |

| New Species | Place | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Heterorhabditis noenieputensis | South Africa | Malan et al., 2014 [91] |

| Heterorhabditis pakistanense | Pakistan | Shahina et al., 2017 [92] |

| Steinernema balochiense | Pakistan | Fayyaz et al., 2015 [93] |

| Steinernema beitlechemi | South Africa | Çimen et al., 2016 [94] |

| Steinernema biddulphi | South Africa | Çimen et al., 2016 [95] |

| Steinernema innovation | South Africa | Çimen et al., 2015 [96] |

| Steinernema poinari | Czech Republic | Mráček and Nermuť 2014 [97] |

| Steinernema pwaniensis | Tanzania | Půža et al., 2017 [98] |

| Steinernema tbilisiensis | Georgia | Gorgadze et al., 2015 [99] |

| Steinernema tophus | South Africa | Stock 2014 [100] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Labaude, S.; Griffin, C.T. Transmission Success of Entomopathogenic Nematodes Used in Pest Control. Insects 2018, 9, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects9020072

Labaude S, Griffin CT. Transmission Success of Entomopathogenic Nematodes Used in Pest Control. Insects. 2018; 9(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects9020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLabaude, Sophie, and Christine T. Griffin. 2018. "Transmission Success of Entomopathogenic Nematodes Used in Pest Control" Insects 9, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects9020072

APA StyleLabaude, S., & Griffin, C. T. (2018). Transmission Success of Entomopathogenic Nematodes Used in Pest Control. Insects, 9(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects9020072