Terpenoid Mixtures as Repellents Against the American Cockroach: Their Synergy and Low Toxicity Against Non-Target Species

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. American Cockroach Rearing

2.2. Chemicals and Treatments

2.3. Bioanalysis of Repellent Activity

2.4. Toxicity Bioassay for Non-Target Species

2.4.1. Guppie Bioassay

2.4.2. Earthworm Bioassay

2.4.3. Mortality Rate (%M) and Biosafety Ratio (BR) Calculation for Guppy Fish and Earthworm

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

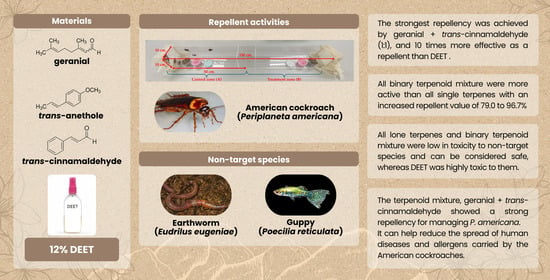

Repellent Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, L.; Wen, J.; Li, S.; Liu, F. Life-history traits from embryonic development to reproduction in the American cockroach. Insects 2022, 13, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhajeri, N.; Alharbi, J.; El-Azazy, O.M.E. The potential of the American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) as a vector of enterobacteriaceae in Kuwait. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, E.S. Cockroaches and food-borne pathogens. Environ. Health Insights 2020, 14, 1178630220913365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangchan, T.; Koosakulchai, V.; Sangsupawanich, P.; Srisuk, B.; Yuenyongviwat, A. Trends of aeroallergen sensitization among children with respiratory allergy in Southern Thailand. Asian Pac. Allergy 2024, 14, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sookrung, N.; Tungtrongchitr, A.; Chaicump, W. Cockroaches: Allergens, component-resolved diagnosis (CRD) and component-resolved immunotherapy. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2020, 21, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondhalekar, A.D.; Appel, A.G.; Thomas, G.M.; Romero, A. A Review of alternative management tactics employed for the control of various cockroach species (Order: Blattodea) in the USA. Insects 2021, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gits, M.P.; Gondhalekar, A.D.; Scharf, M.E. Impacts of bioassay type on insecticides resistance assessment in the German cockroach (Blattodea: Ectobiidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2023, 60, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.M.; Mustafa, R.; Samiullah, K.; Abbas, S.K.; Zahra, K.; Khan, A.A.; Yaqub, A.; Naseem, S.; Yaqoob, R. Toxicity and resistance of American cockroach, Periplaneta americana L. (Blattodea: Blattidae) against malathion. Afr. Entomol. 2017, 25, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Fan, R.; Naz, H.; Bamisile, B.S.; Hafeez, M.; Ghani, M.I.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: Challenges and control strategies. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhahraei, A.R.; Sadhafipour, A.; Vatandoost, H. Control of American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) in municipal sewage disposal system, central Iran. J. Arthropod Borne Dis. 2018, 12, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, G.; Matsu, D.; Bailey, B. DEET-based insect repellents: Safety implications for children and pregnant and lactating women. Can. Med. Assosc. J. 2023, 169, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Swale, D.R.; Bloomquist, J.R. Is DEET a dangerous neurotoxicant? Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2068–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, J.A.; Guiney, P.D.; Nikiforow, A.I. Assessment of the environmental fate and ecotoxicity of N,N-diethyl-m-tolumide (DEET). Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2012, 8, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digha, B.; O’Neal, J.; Appel, A.; Jackai, L. Integrated pest management of the german cockroach (Blattodea: Blattellidae) in manufactured homes in rural North Carolina. Fla. Entomol. 2016, 99, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passara, H.; Soonwera, M.; Arhamad-Armeen, N.; Sittichok, S.; Jintanasirinurak, S. Efficacy of plant essential oils for repelling against American cockroach adults (Periplaneta americana L.). Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2025, 21, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sittichok, S.; Phaysa, W.; Soonwera, M. Repellency activity of essential oil on Thai local plants against American cockroach (Periplaneta americana L.; Blattidae: Blattodea). Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2013, 9, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Sittichok, S.; Passara, H.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Sinthusiri, J.; Murata, K.; Soonwera, M. Synergistic larvicidal and pupicidal effects of monoterpene mixtures against Aedes aegypti with low toxicity to guppies and honeybees. Insects 2025, 16, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittichok, S.; Passara, H.; Sinthusiri, J.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Puwanard, C.; Murata, K.; Soonwera, M. Synergistic larvicidal and pupicidal toxicity and the morphological impact of dengue vector (Aedes aegypti) induced by geranial and trans- cinnamaldehyde. Insects 2024, 15, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonwera, M.; Sinthusiri, J.; Passara, H.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Puwanard, C.; Sittichok, S.; Murata, K. Combinations of lemongrass and star anise essential oils and their main constituent: Synergistic housefly repellency and safety against non-target organisms. Insects 2024, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonwera, M.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Aungtikun, J.; Sittichok, S. Combinations of plant essential oils and their major compositions inducing mortality and morphological abnormality of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R. Essential oils for the development of eco-friendly mosquito larvicides: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moungthipmalai, T.; Puwanard, C.; Aungtikun, J.; Sittichok, S.; Soonwera, M. Ovicidal toxicity of plant essential oils and their major constituents against two mosquito vectors and their non-target aquatic predators. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masyita, A.; Sari, R.M.; Astuti, A.D.; Yasir, B.; Rumata, N.R.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactic compound of essential oils, their roles in human health an potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem. X 2022, 19, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moungthipmalai, T.; Soonwera, M. Adulticidal activity against housefly (Musca domestica L.: Muscidae: Diptera) of combinations of Cymbopogon citratus and Eucalyptus globulus essential oils and their major constituents. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2023, 19, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Aungtikun, J.; Soonwera, M.; Sittichok, S. Insecticidal synergy of essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus (Stapf.), Myristica fragrans (Houtt.) and Illicium verum Hook.f. and their major active constitutes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 164, 113386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Sabier, M.; Zhang, T.; Deng, J.; Song, X.; Liao, Z.; Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Cao, Y.; et al. Trans-anethole is apotent toxic fumigant that partially inhibits rusty grain beetle (Crytolestes ferrugineus) accetylcholinesterase activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 161, 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, L.; Hamid, A.; Raza, F.A.; Chaudhary, S.U.; Iman, K.; Ajmal, S.; Younas, H.; Khalid, K.; Iqbal, M.; Tasadduq, R. Repellent activity of trans-anethole and tea tree oil against Aedes aegypti and their interaction with OBP1,a protein involved in olfaction. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2022, 170, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonwera, M.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Takawirapat, W.; Sittichok, S. Ovicidal and repellent activities of several plat essential oils against Periplaneta americana L. and enhanced activities from their combined formulation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, A.; Yusoff, S.N.M.; Wong, S.T.S.; Yusof, N.; Othman, H.; Hussein, M.Z.; Phillip, E. Development to anti-mosquito spray formulation based on lipid-core nanocapsules loaded with cinnamaldehyde for fabrics application. Fibers Polym. 2022, 23, 2156–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aungtikun, J.; Soonwera, M. Improved adulticidal activity against Aedes aegypti (L.), and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) from synergy between Cinnamomum spp. essential oils. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passara, H.; Sittichok, S.; Puwanard, C.; Sinthusiri, J.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Murata, K.; Soonwera, M. Anise and fennel essential oils and their combinations as natural and safe housefly repellents. Insects 2025, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solo, I.G.; Santos, W.S.; Branco, L.G.S. Citral as anti-inflammatory agents: Mechanisms, therapeutic potential and perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. Nat. Prod. 2025, 7, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadian, R.; Dehkordi, S.B. A comprehensive review of the neurological effect of anethole. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 18, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.D.S.; Marques, J.N.J.; Linhares, E.P.M.; Bonora, C.M.; Costa, E.T.; Saraiva, M.F. Review of anticancer activity of monoterpenoids: Geraniol, nerol, geranial and neral. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 362, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasanami, M.; Hustedt, J.; Alexander, N.; Horstick, O.; Bowman, L.; Hii, J.; Echaubard, P.; Braack, L.; Overgaard, H.J. Dose anthropogenic introduction of guppy fish (Poecilia reticulata) impact faunal species diversity and abundance in natural aquatic habitats? A systematic review protocol. Environ. Evid. 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, S.; Gavinelli, F.; Lazzarini, F.; Paoletti, M.G. Soil Biological quality index based on earthworms(QBS-e).A new way to use earthworms as bioindicators in agroecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilan, M.; Nanthakumar, S. Impact of agricultural practices on earthworm biodiversity in different agroecosystems. Agric. Sci. Dig. 2017, 37, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Guideline for Testing of Chemicals No207, Earthworm, Acute Toxicity Tests; Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wheeler, M.W.; Park, R.M.; Bailer, A.J. Comparing median lethal concentration values using confidence interval overlap or ratio tests. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candy, S.G. The application of generalized linear mixed models to multi-level sampling for insect population monitoring. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2000, 7, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngegba, P.M.; Gui, G.F.; Khalid, M.Z.; Zhong, G. Use of botanical pesticides in agriculture as an alternative to synthetic pesticides. Agriculture 2022, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirak, M.S.S.; Canpolat, E. Plant-based bioinsecticides for mosquito control: Impact on insecticide resistance and disease transmission. Insects 2022, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.K.; Cho, S.; Lee, G.C.; Lee, D.E.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, I.Y.; Ko, C.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Molecular analysis of insecticides resistance mutation frequencies in five cockroach species from Korea. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 212, 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Imran, A.B. Biomimetic and synthetic advances in natural pesticides: Balancing effiency and environmental safety. J. Chem. 2025, 2025, 1510186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyotsna, B.; Patil, S.; Prakash, Y.S.; Rathnagiri, P.; Kishor, P.B.K.; Jalaja, N. Essential oils from plant resources as potent insecticides and repellents: Current status and future perspectives. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 61, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Ai, S.; Fu, X.; Fan, B.; Li, W.; Liu, Z. Aquatic life criteria derivation and ecological risk assessment of DEET in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, N.F.; Fu, L.; Dainese, M.; Kiaer, L.P.; Hu, Y.Q.; Xin, F.; Goulson, D.; Woodcock, B.A.; Vanbergen, A.J.; Spurgeon, D.J.; et al. Pesticides have negative effects on non-target organisms. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambolena, J.S.; Zunino, M.P.; Herrera, J.M.; Pizzolitto, R.P.; Areco, V.A.; Zygadlo, J.A. Terpenenes: Natural products for controlling insects of importance to human health-A structure-Activity relationship study. Psyche 2016, 2016, 4595823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B.; Norris, E.B. Bioinsecticide synergy: The good, the bad and the unknown. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2024, 42, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, E.; Gross, A.D.; Kimber, M.J.; Bartholomay, L.; Coats, J.R. Plant terpenoids modulate α-adrenergic type1 octopamine receptor(PaOA1) isolated from the American cockroach (Periplaneta americana). Adv. Bioration. Control. Med. Vet. Pests 2018, 12, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enan, E. Insectticidal activity of essential oils: Octopaminergic sites of action. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2001, 130, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deletre, E.; Martin, T.; Dumenil, C.; Chandre, F. Insecticide resistance modifies mosquito repose to DEET and natural repellents. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengoni, S.L.; Alzogaray, R.A. Deltamethrin-resistant german cockroaches are less sensitive to the insect repellents DEET and IR3535 than non-resistant individuals. J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y. Global perspective of insecticide resistance in bed bugs and management options. Entomol. Res. 2025, 55, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernado, S.S.S.T.; Jayasooriya, R.G.P.T.; Samarakoon, K.W.; Wijegnawardana, N.D.A.; Alahakoon, S.B. Citrus-based bio-insect repellent-A review on historical and emerging trends in utilizing phytochemicals of citrus plants. J. Toxicol. 2024, 28, 6179226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Ethnobotabical knowledge on botanical repellents employed in the African region against mosquito vectors-A review. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 167, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, F.; Tramut, C.; Salem, A.; Lienard, E.; Deletre, E.; Franc, M.; Martin, T.; Duavallet, G.; Jay-Robert, P. The repellency of lemongrass oil against stable flies, tested using video tracking. Parasite 2013, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, M.K.; Kumar, N. Evaluation of insecticidal properties of cinnamaldehyde and cuminaldehyde against Sitophilus zemais. Inter. J. Entomol. Res. 2024, 9, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tak, J.H.; Isman, M.B. Metabolism of citral, the major constitute of lemongrass oil, in the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni, and effects of enzyme inhibitors on toxicity and metabolism. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 133, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.; Rogalaka, J.; Wyszkowska, J.; Stankiewicz, M. Molecular targets for components of essential oils in the insect nervous system—A review. Molecules 2017, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziegelewska, A.; Lubawy, J.; Adamski, Z. Insceticidal effects of substances from cinnamon bark-eugenol, trans-cinnamaldehyde and cinnamaldehyde on Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 111, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Wu, S.; Ou, M.; Liao, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Li, R.; Ming, L. Citral: A plant-derived compound with excellent potential for sustainable crop protection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 29328–29345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabahi, Q.; Hamiduzzaman, M.M.; Barajas-Perez, J.S.; Tapia-Gonzalez, J.M.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Toxicity of anethole and the essential oils of lemongrass and sweet marigold to parasitic mite Varroa destructor and their selective for honey bee (Apis mellifera) workers and larvae. Psyche 2018, 2018, 6196289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugger, B.P.; Martinez, L.C.; Plata-Rueda, A.; de Castro e Castro, B.M.; Soares, M.A.; Wilcken, C.F.; Carvalho, A.G.; Serrao, J.E.; Zanuncio, J.C. Bioactive of the Cymbopogon citratus (Poaceae) essential oil and its terpenoids constituents on the predatory bug, Podisus nigrispinus (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pevela, R.; Morshedloo, M.R.; Mumivand, H.; Khorsand, G.J.; Karami, A.; Maggi, F.; Desneux, N.; Benelli, G. Phenolic monoterpene-rich essential oils from Apiaceae and Lamiaceae species: Insecticidal activity and safety evaluate on non-target earthworms. Entomol. Gen. 2020, 4, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.Y.; Trinh, N.T.; Ahn, S.G.; Kim, S. Cinnamaldehyde protects against oxidative stress and inhibits the TNF-α-induced inflammatory response in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D. Ethnopharmacology, chemical composition and functions of Cymbopogon citratus. Chin. Herb. Med. 2023, 16, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orffer, Z.; Zyl, J.H.C.; Semwogerere, F.; Mapiye, C.; Strydom, P.E. Substituting monensin in lamb finisher diets with a citral and linalool blend on meat physiocochemical properties, shelf display stability and fatty acid composition. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2025, 321, 116256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motuzova, T.; Gavlova, A.; Smutna, K.; Repecka, L.; Vrablova, M. Environmental impact of DEET: Monitoring in aquatic ecosystems and ecotoxicity assessment. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 6342–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.N.; Goswami, R.; Pal, A. The insect repellent: A silent environmental chemical toxicant to the health. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2017, 50, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swale, D.R.; Sun, B.; Tong, F.; Bloomquist, J.R. Neurotoxicity and mode of action of N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide(DEET). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Constituent a | RI b | KI c | Percentage of Total Composition | ID d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. citratus | I. verum | C. verum | |||||

| 1 | α-Thujene | 931 | 930 | – | 0.22 ± 0.02 | – | RI, Std |

| 2 | α-Pinene | 949 | 949 | 3.40 ± 0.06 | – | 0.51 ± 0.04 | RI, Std |

| 3 | Camphene | 951 | 952 | – | – | 0.61 ± 0.04 | RI, Std |

| 4 | Sabinene | 967 | 969 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 5 | β-pinene | 979 | 979 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 6 | β-Myrcene | 990 | 991 | – | – | 0.32 ± 0.11 | RI, Std |

| 7 | α-Phellandrene | 1003 | 1003 | – | – | 0.42 ± 0.11 | RI, Std |

| 8 | δ-3-Carene | 1006 | 1006 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 9 | Benzyl alcohol | 1009 | 1009 | – | – | 12.5 ± 0.69 | RI, Std |

| 10 | α-Terpinene | 1012 | 1012 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | – | 0.21 ± 0.09 | RI, Std |

| 11 | Limonene | 1032 | 1032 | – | 1.85 ± 0.08 | 0.63 ± 0.09 | RI, Std |

| 12 | 1,8-Cineole | 1033 | 1033 | 10.60 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.06 | RI, Std |

| 13 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 1049 | 1050 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 14 | γ-Terpinene | 1051 | 1052 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | – | – | RI, Std |

| 15 | Terpinolene | 1089 | 1088 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 16 | Linalool | 1101 | 1101 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | – | – | RI, Std |

| 17 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1180 | 1179 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 18 | α-Terpineol | 1190 | 1191 | – | 0.21 ± 0.01 | – | RI, Std |

| 19 | Neral | 1216 | 1216 | 24.80 ± 4.62 | – | – | RI |

| 20 | trans-Cinnamaldehyde | 1221 | 1221 | – | – | 75.21 ± 2.73 | RI, Std |

| 21 | Nerol | 1232 | 1232 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 22 | Geraniol | 1235 | 1235 | 4.50 ± 0.00 | – | – | RI, Std |

| 23 | Geranial | 1246 | 1246 | 46.45 ± 2.26 | – | – | RI, Std |

| 24 | p-Anisaldehyde | 1247 | 1247 | – | 1.21 ± 0.08 | – | RI, Std |

| 25 | Linalyl acetate | 1261 | 1261 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 26 | trans-Anethole | 1283 | 1283 | – | 94.29 ± 2.04 | – | RI, Std |

| 27 | Eugenol | 1355 | 1355 | – | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 2.40 ± 0.86 | RI, Std |

| 28 | Neryl acetate | 1368 | 1368 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 29 | α-Copaene | 1378 | 1378 | – | – | 1.80 ± 0.41 | RI |

| 30 | Geranyl acetate | 1382 | 1381 | 3.30 ± 0.02 | – | – | RI, Std |

| 31 | Cinnamyl acetate | 1415 | 1414 | – | – | 2.30 ± 0.53 | RI, Std |

| 32 | Cinnamic acid | 1462 | 1462 | – | – | 0.50 ± 0.19 | RI, Std |

| 33 | trans-Nerolidol | 1566 | 1565 | – | – | – | RI, Std |

| 34 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1581 | 1581 | 2.50 ± 0.02 | – | – | RI, Std |

| 35 | Cadalene | 1658 | 1658 | – | – | 0.20 ± 0.05 | RI |

| Total identified (%) | 96.60 ± 1.3 | 99.00 ± 0.95 | 98.22 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Color | Pale yellow | Pale yellow | Pale yellow | ||||

| Yield (% v/w) | 1.14 | 3.13 ± 0.08 | 1.05 | ||||

| Treatment | Repellent Concentration | Estimated Concentration (µL/cm3) | CI95 (µL/cm3) | Chi-Square | Slope ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| geranial | RC25 | 3.1 | 1.3–5.0 | 4.654 | −2.532 ± 0.552 |

| RC50 | 9.1 | 6.5–12.9 | |||

| RC90 | 20.2 | 13.7–25.1 | |||

| trans-anethole | RC25 | 2.9 | 1.7–4.1 | 6.687 | −0.745 ± 0.495 |

| RC50 | 7.1 | 5.6–10.3 | |||

| RC90 | 15.1 | 11.4–20.5 | |||

| trans-cinnamaldehyde | RC25 | 2.0 | 0.5–3.1 | 6.318 | −1.694 ± 0.463 |

| RC50 | 6.2 | 4.9–8.8 | |||

| RC90 | 14.2 | 10.9–22.4 | |||

| geranial + trans-cinnamaldehyde | RC25 | 0.2 | 0.05–0.3 | 138.573 | −1.269 ± 1.156 |

| RC50 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.8 | |||

| RC90 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.6 | |||

| trans-anethole + trans-cinnamaldehyde | RC25 | 0.6 | 0.2–0.8 | 56.402 | −0.587 ± 0.767 |

| RC50 | 1.6 | 0.7–2.4 | |||

| RC90 | 4.6 | 2.3–5.8 | |||

| geranial + trans-anethole | RC25 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.8 | 114.009 | −1.529 ± 0.958 |

| RC50 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.2 | |||

| RC90 | 1.3 | 0.8–1.9 | |||

| DEET | RC25 | 1.3 | 0.8–2.0 | 18.153 | −1.668 ± 1.227 |

| RC50 | 3.0 | 1.3–4.8 | |||

| RC90 | 6.5 | 3.4–8.6 |

| Treatment | Concentration (mL/kg) | Mortality Rate (%) (Mean ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 10 | Day 15 | ||

| geranial | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| trans-anethole | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| trans-cinnamaldehyde | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| geranial + trans-cinnamaldehyde | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| trans-anethole + trans-cinnamaldehyde | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| geranial + trans-anethole | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| distilled water | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| DEET | 0.1 | 15.0 ± 2.7 c | 21.5 ± 3.7 c | 21.5 ± 3.7 c | 25.5 ± 2.9 c |

| 0.5 | 56.0 ± 4.7 b | 56.0 ± 4.7 b | 60.0 ± 3.8 b | 60.0 ± 3.8 b | |

| 1.0 | 96.0 ± 4.2 a | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | |

| ANOVAF0.01, Dftotal | **, 119 | **, 119 | **, 119 | **, 119 | |

| P-value | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | |

| Treatment | Concentration (mL/L) | Mortality Rate (%) (Mean ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 10 | Day 15 | ||

| geranial | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| trans-anethole | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| trans-cinnamaldehyde | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| geranial + trans-cinnamaldehyde | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| trans-anethole + trans-cinnamaldehyde | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| geranial + trans-anethole | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| distilled water | 0.1 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d |

| 0.5 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| 1.0 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | |

| DEET | 0.1 | 25.0 ± 3.8 c | 30.0 ± 4.7 c | 30.0 ± 4.7 c | 35.0 ± 4.9 c |

| 0.5 | 60.0 ± 3.7 b | 60.0 ± 3.7 b | 65.0 ± 4.8 b | 65.0 ± 4.8 b | |

| 1.0 | 98.0 ± 3.3 a | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | |

| ANOVAF0.01, Dftotal | **, 119 | **, 119 | **, 119 | **, 119 | |

| p-value | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Passara, H.; Moungthipmalai, T.; Laosinwattana, C.; Sittichok, S.; Murata, K.; Soonwera, M. Terpenoid Mixtures as Repellents Against the American Cockroach: Their Synergy and Low Toxicity Against Non-Target Species. Insects 2026, 17, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010065

Passara H, Moungthipmalai T, Laosinwattana C, Sittichok S, Murata K, Soonwera M. Terpenoid Mixtures as Repellents Against the American Cockroach: Their Synergy and Low Toxicity Against Non-Target Species. Insects. 2026; 17(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010065

Chicago/Turabian StylePassara, Hataichanok, Tanapoom Moungthipmalai, Chamroon Laosinwattana, Sirawut Sittichok, Kouhei Murata, and Mayura Soonwera. 2026. "Terpenoid Mixtures as Repellents Against the American Cockroach: Their Synergy and Low Toxicity Against Non-Target Species" Insects 17, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010065

APA StylePassara, H., Moungthipmalai, T., Laosinwattana, C., Sittichok, S., Murata, K., & Soonwera, M. (2026). Terpenoid Mixtures as Repellents Against the American Cockroach: Their Synergy and Low Toxicity Against Non-Target Species. Insects, 17(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010065