Mapping Antennal Sensilla of Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) as the First Step in Understanding Overwintering Aggregation Behavior

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Collection and Sample Preparation

2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3. Sensilla Mapping and Enumeration

3. Results

3.1. Gross Morphology of Antennae

3.2. Sensilla Types and Arrangement

4. Discussion

4.1. Scape

4.2. Pedicel

4.3. Flagellomeres

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOAJ | Directory of Open-Access Journals |

| SA | Sensilla ampullacea |

| SB | Sensilla basiconica |

| SBm | Sensilla bell-mouthed |

| SCa | Sensilla campaniformia |

| SCh | Sensilla chaetica |

| SCo | Sensilla coeloconica |

| ST | Sensilla trichoidea |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- Schwarz, J.; Gries, R.; Hillier, K.; Vickers, N.; Gries, G. Phenology of semiochemical-mediated host foraging by the western boxelder bug, Boisea rubrolineata, an aposematic seed predator. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Traverso, J.H.; Sanabria, E.A. New record of the boxelder bug Boisea trivittata in Argentina suggests a rapid spread. Rev. Peru. Biol. 2025, 32, e28983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.C.; Shepherd, L. The life history and control of the boxelder bug in Kansas. Trans. Kans. Acad. Sci. 1937, 40, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, M.E. The seasonal behavior and ecology of the boxelder bug (Leptocoris trivitatus) in Minnesota. Ecology 1952, 33, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, T.J.; Lee, D.H.; Bergh, J.C.; Morrison, W.R., III; Leskey, T.C. Presence of the invasive brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) on home exteriors during the autumn dispersal period: Results generated by citizen scientists. Agric. Forest Entomol. 2019, 21, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkley, D.B. Characteristics of home invasion by the brown marmorated stink bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 2012, 47, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J. Stink bugs delay 10,000 Hyundai and Kia cars following increased biosecurity checks. Drive, 15 December 2019. Available online: https://www.drive.com.au/news/stink-bugs-delay-10-000-hyundai-and-kia-cars-following-increased-biosecurity-checks/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Schowalter, T.D. Overwintering aggregation of Boisea rubrolineatus (Heteroptera: Rhopalidae) in western Oregon. Environ. Entomol. 1986, 15, 1055–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D. Insect antennae. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 1964, 9, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.R.; Hanson, B.S.; Ignell, R. Characterization of antennal trichoid sensilla from female southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Chem. Senses 2009, 34, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, W.S. Odorant reception in insects: Roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, H.Z.; Levinson, A.R.; Muller, B.; Steinbrecht, R.A. Structural of sensillum, olfactory perception, and behavior of the bed bug, Cimex lectularius, in response to its alarm pheromone. J. Insect Physiol. 1974, 20, 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harraca, V.; Ignell, R.; Löfstedt, C.; Ryne, C. Characterization of the antennal olfactory system of the bed bug (Cimex lectularius). Chem. Senses 2010, 35, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.F.; Moon, R.D.; Kells, S.A.; Mesce, K.A. Morphology, ultrastructure and functional role of antennal sensilla in off-host aggregation by the bed bug, Cimex lectularius. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2014, 43, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowińska, A.; Brożek, J. Morphological study of the antennal sensilla in Gerromorpha (Insecta: Hemiptera: Heteroptera). Zoomorphology 2017, 136, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowińska, A.; Brożek, J. The variability of antennal sensilla in Naucoridae (Heteroptera: Nepomorpha). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.C.A.; Capdeville, G.; Moraes, M.C.B.; Falcao, R.; Solino, L.F.; Laumann, R.A.; Silva, J.P.; Borges, M. Morphology, distribution and abundance of antennal sensilla in three stink bug species (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Micron 2010, 41, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga-Segura, J.; Valdéz-Carrasco, J.; Castrejón-Gómez, V.R. Sense organs on the antennal flagellum of Leptoglossus zonatus (Heteroptera: Coreidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2013, 106, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taszakowski, A.; Masłowski, A.; Daane, K.M.; Brożek, J. Closer view of antennal sensory organs of two Leptoglossus species (Insecta, Hemiptera, Coreidae). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.F. The Insects, Structure and Function, 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 610–652. Available online: www.cambridge.org/9780521113892 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Iwasaki, M.; Itoh, T.; Yokohari, F.; Tominaga, Y. Identification of antennal hygroreceptive sensillum and other sensilla of the firefly, Luciola cruciata. Zool. Sci. 1995, 12, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renthal, R.; Velasquez, D.; Olmos, D.; Hampton, J.; Wergin, W.P. Structure and distribution of antennal sensilla of the red imported fire ant. Micron 2003, 34, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.F.; Moon, R.D.; Kells, S.A. Off-host aggregation behavior and sensory basis of arrestment by Cimex lectularius (Heteroptera: Cimicidae). J. Insect Physiol. 2009, 55, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIver, S.B. Structure of cuticle mechanoreceptors of arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1975, 20, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharuk, R.Y. Antennae and sensilla. In Comprehensive Insect Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology; Kerkut, G.A., Gilbert, L.I., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1985; Volume 6, pp. 29–63. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, T.A. Morphology and development of the peripheral olfactory organs. In Insect Olfaction; Hansson, B.S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stange, G.; Stowe, S. Carbon-dioxide sensing structures in terrestrial arthropods. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999, 47, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, V.D.C. High resolution ultrastructural investigation of insect sensory organs using field emission scanning electron microscopy. In Microscopy: Science, Technology, Applications, and Education; Mendez, V.A., Diaz, J., Eds.; Formatex Research Center: Badajoz, Spain, 2011; pp. 321–328. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:32113298 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Hartenstein, V. Development of insect sensilla. Compr. Mol. Insect Sci. 2025, 1, 379–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharuk, R.Y. Ultrastructure and function of insect chemosensilla. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1980, 25, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Meng, L.; Zhou, Y. Fine structure and distribution of antennal sensilla of stink bug Arma chinensis (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Acta Entomol. Fenn. 2015, 25, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.S. Transduction mechanisms of mechanosensilla. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1988, 33, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.S.; Wang, X.Q.; Li, D.T.; Song, D.D.; Zhang, C.X. Three-dimensional architecture of a mechanoreceptor in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, revealed by FIB-SEM. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 379, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Parveen, S.; Brożek, J.; Dey, D. Antennal sensilla of phytophagous and predatory pentatomids (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae): A comparative study of four genera. Zool. Anz. 2016, 261, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Brożek, J.; Dai, W. Functional morphology and sexual dimorphism of antennae of the pear lacebug Stephanitis nashi (Hemiptera: Tingidae). Zool. Anz. 2020, 286, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakilam, S.; Brożek, J.; Chajec, Ł.; Poprawa, I.; Gaidys, R. Ultra-morphology and mechanical function of the trichoideum sensillum in Nabis rugosus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Insecta: Heteroptera: Cimicomorpha). Insects 2022, 13, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebora, M.; Salerno, G.; Piersanti, S. Aquatic insect sensilla: Morphology and function. In Aquatic Insects; Del-Claro, K., Guillermo, R., Eds.; Springer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetak, D. Detection of substrate vibration in Neuropteroidea: A review. Acta Zool. Fenn. 1998, 209, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zill, S.N.; Ridgel, A.; DiCaprio, R.; Frazier, S. Load signaling by cockroach trochanteral campaniform sensilla. Brain Res. 1999, 822, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zill, S.N.; Buschges, A.; Schmitz, J. Encoding of force increases and decreases by tibial campaniform sensilla in the stick insect, Carausius morosus. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2011, 197, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.M.; Dinges, G.F.; Haberkorn, A.; Gebehart, C.; Buschges, A.; Zill, S.N. Gradients in mechano-transduction of force and body weight in insects. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2020, 58, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleineidam, C.; Tautz, J. Perception of Carbon Dioxide and Other “Air-Condition” Parameters in the Leaf Cutting ant Atta cephalotes. Sci. Nat. 1996, 83, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrecht, R.A. Structure and Function of Insect Olfactory Sensilla. In Ciba Foundation Symposium 200—Olfaction in Mosquito-Host Interactions; Novartis Foundation Symposia; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altner, H.; Prillinger, L. Ultrastructure of invertebrate chemo-, thermo-, and hygroreceptors and its functional significance. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1980, 67, 69–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.W.; Ball, H.J. Antennal hygroreceptors of the milkweed bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus (Dallas) (Hemiptera, Lygaeidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1959, 52, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, K. Behavioural attributes of Oxycarenus laetus Kirby towards different malvaceous seeds. Phytophaga 1988, 2, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

| Subtype | Description and Location | Representative Image |

|---|---|---|

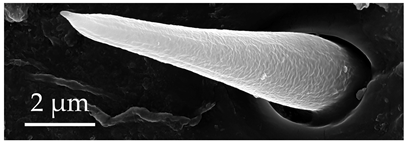

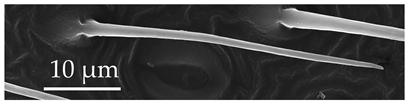

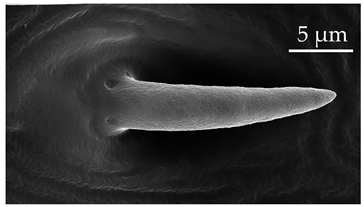

| ST1 | ST1 are short, straight, cone-like sensilla, with a flexible socket and a smooth surface lacking grooves, terminating with an apical pore. These sensilla are found only on the distal end of the scape and pedicel at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| ST2 | ST2 are short, thin hair-like sensilla, with a base inserted in a flexible socket, grooves along the surface, and an aporous, pointed tip. ST2 protrude at an angle to the surface, directed distally. ST2 are singularly scattered on all the antennomeres, except for the distiflagellomere, at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

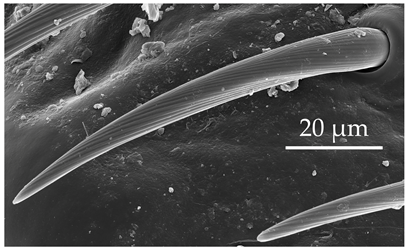

| ST3 | ST3 are straight hairs with a flexible socket, ribbed surface, and an aporous, blunt tip. The ribs extend from the base to the tip of the sensilla. Mid-shaft, the diameter of this sensillum stem is subequal. ST3 are larger than ST2 and present on all antennomeres at a density of 5–7 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

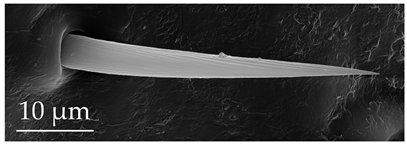

| ST4 | ST4 are long, hair-like sensilla, embedded in a flexible socket, bearing a ribbed surface that starts above the base and ends before the tip. These sensilla are aporous. The shaft diameter uniformly tapers along the whole length, with a long thin pointed tip. They are found on the scape and distiflagellomere at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

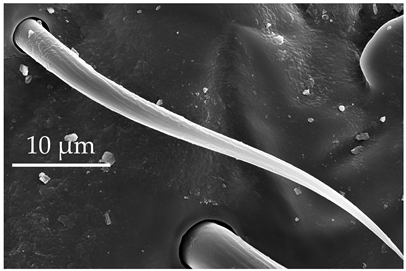

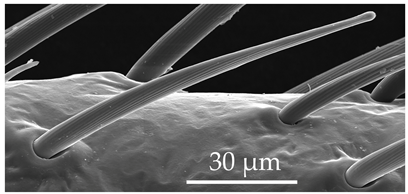

| ST5 | ST5 are long, straight or slightly curved, thin hair-like structures, arising from an inflexible socket. The sensilla wall is smooth with no pores or grooves on the surface. ST5 are uniformly distributed exclusively on the distiflagellomere at densities of 9–12 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| Subtype | Description | Representative Image |

|---|---|---|

| SCh1 | In addition to the general description of the group, SCh1 subtypes are of intermediate length. SCh1 are slightly curved and become parallel with the surface oriented distally. SCh1 are evenly distributed on all antennomeres at densities of 6–9 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| SCh2 | SCh2 are long sensilla with a rounded tip. SCh2 are scattered around the circumference of the scape and pedicel segments at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

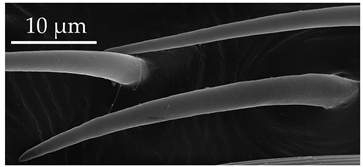

| SCh3 | SCh3 are short sensilla. Proportional to length, they are thicker than SCh1 and SCh2 and branched at the tip. SCh3 are sparse, with a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2, and are found on the scape only. |  |

| SCh4 | SCh4 are short, curved, and distributed on the scape and distiflagellomere at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| Subtype | Description | Representative Image |

|---|---|---|

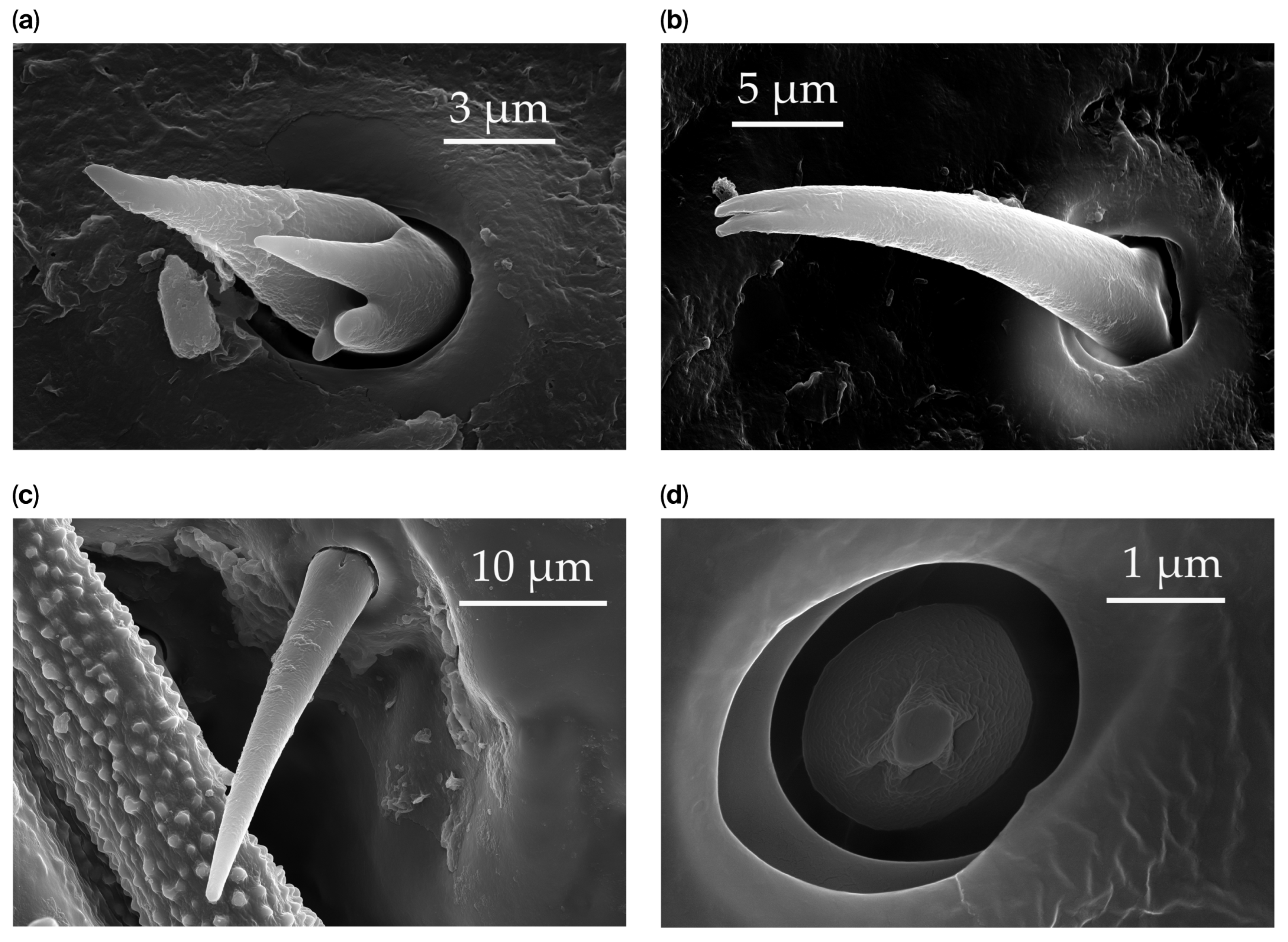

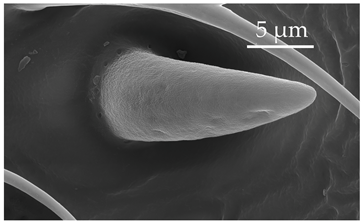

| SB1 | SB1 have a flexible socket with a pore at the base. These are branched or unbranched cones (Figure 3a,b). The distal stem of SB1 is stiff and blunt. SB1 are found individually near the proximal end of the scape and pedicel (Figure 3c) at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| SB2 | SB2 have an inflexible socket and a distinctly porous surface. The sensillum stem is wide and stiff, with several gland pores at the base. Numerous raised ellipsoid shaped pores are present over the entire surface. SB3 are very few and occur on the distiflagellomere at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

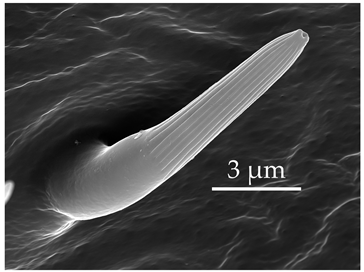

| SB3 | SB3 are cone-like structures that arise from an inflexible socket, with a proportionately thick stem and a pointed tip. They are either straight or bent towards the distal end of the antenna. There are 8 to 10 large pores at the base. Numerous comma-shaped nano-pores are distributed over the entire sensillum surface. These sensilla are relatively numerous on the distiflagellum at densities of 5–8 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| SB3a | SB3a are similar to SB3 but distinctly shorter. They are cone-shaped, slightly curved, asymmetrical-bulbous structures with pores on the entire surface. Around the sensillum base, there are several gland pores. SB3 are present only on the distiflagellomere and few in number, with a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| SB4 | SB4 are very short cones embedded in an inflexible socket, with a distal end tapering to a pore. Proximal to the base, these sensilla are smooth, with deep longitudinal grooves occurring on the mid-shaft and extending to the end. Most of these sensilla are found to be strongly curved and oriented distally. SB4 are numerous but scattered on the distiflagellomere at densities of 9–10 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

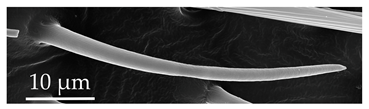

| SB5 | Of the SB group, SB5 are long sensilla. SB5 have an inflexible socket, with longitudinal shallow grooves present along the entire sensillum. Within these grooves, there are linearly arranged pores. SB5 occur exclusively on the distiflagellomeres at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

| Subtype | Description | Representative Image |

|---|---|---|

| SCo1 | SCo1 are short pegs inserted deeply in the pit. The distal end of the sensilla tapers into a relatively wide opening. These sensilla are not numerous and are found exclusively on the dorsal surface of the distiflagellomere at a density of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

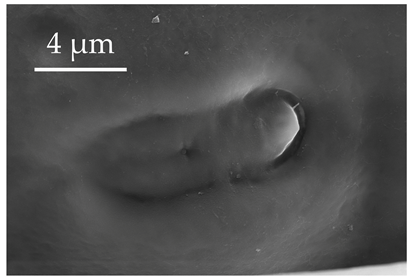

| SCo2 | SCo2 protrude from a sensillum pit. The distal end of these sensilla taper into a terminal pore similar to SCo1, but the pores tend to be smaller in diameter. These sensilla are located in a grouping of five sensilla, laterally on the caudal or outer-facing surfaces of the distal pedicel and basiflagellomere (Figure 3). These sensilla are consistent in number, but their arrangement/pattern varies among individuals. |  |

| Note: the pore to the left of SCo2 is a Sensillum ampullaceum (SA). |

| Subtype | Description | Representative Image |

|---|---|---|

| SCa * | SCa are flat, oval, and cupola-shaped sensilla with flexible sockets and a single central pore. SCa occur in groups of 4–5 located at the base of the scape, but they also occur singly across all segments, usually in areas more susceptible to stress, at densities of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

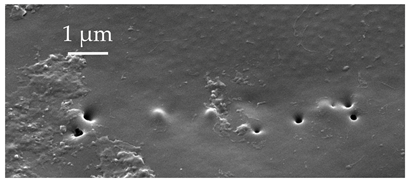

| SA | These are small pegs embedded in a small tube, with only a round opening visible from the surface. In B. trivittata, they are found scattered on the scape, pedicel, and basiflagellomere at densities of less than 5 sensilla per 100 μm2. |  |

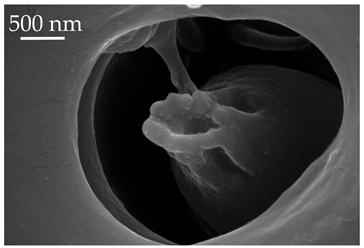

| SBm | SBm are funnel-shaped pits with multiple cuticular folds. Only one sensillum is present on the articulated joint connecting the pedicel and the basiflagellomere. |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sharma, A.; Kells, S.A. Mapping Antennal Sensilla of Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) as the First Step in Understanding Overwintering Aggregation Behavior. Insects 2026, 17, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010006

Sharma A, Kells SA. Mapping Antennal Sensilla of Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) as the First Step in Understanding Overwintering Aggregation Behavior. Insects. 2026; 17(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Anika, and Stephen A. Kells. 2026. "Mapping Antennal Sensilla of Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) as the First Step in Understanding Overwintering Aggregation Behavior" Insects 17, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010006

APA StyleSharma, A., & Kells, S. A. (2026). Mapping Antennal Sensilla of Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) as the First Step in Understanding Overwintering Aggregation Behavior. Insects, 17(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010006