Foraging Patterns of Two Sympatric Wasp Species: The Worldwide Invasive Polistes dominula and the Native Hypodynerus labiatus

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

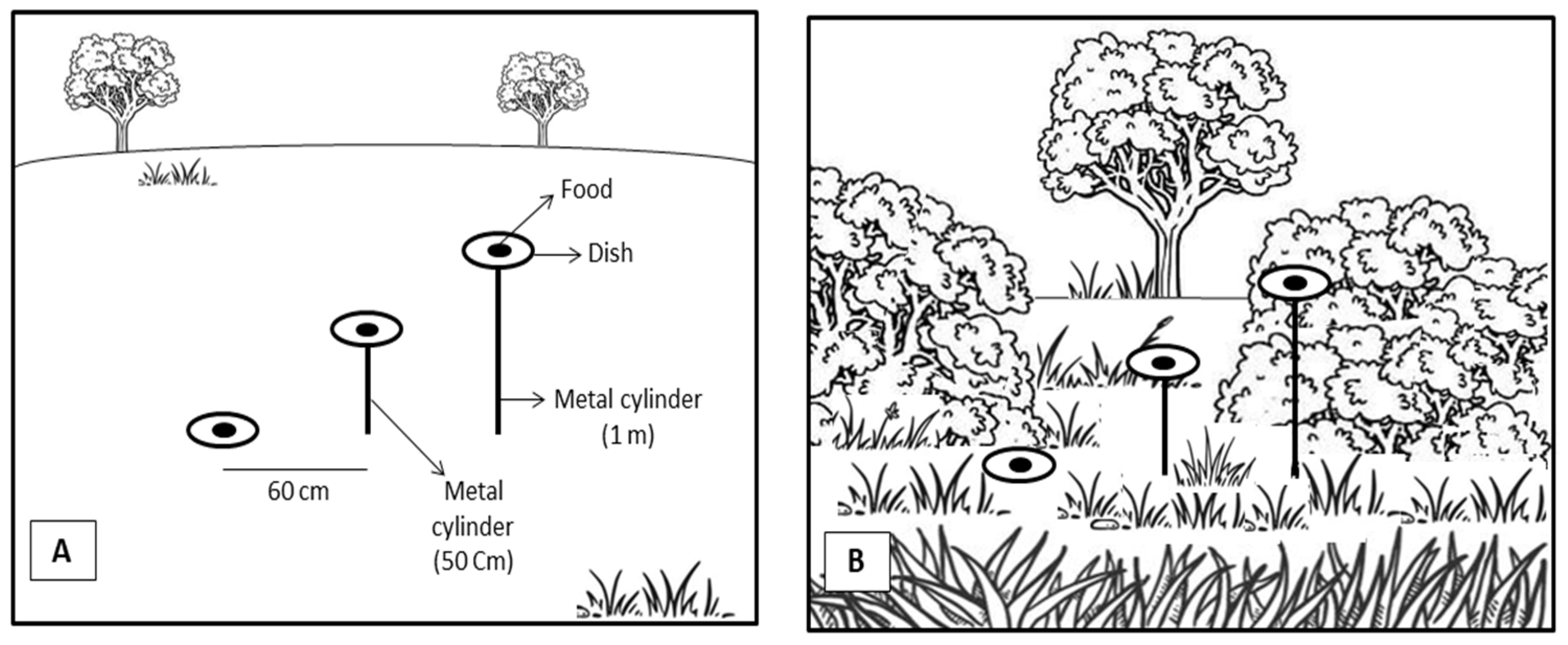

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results

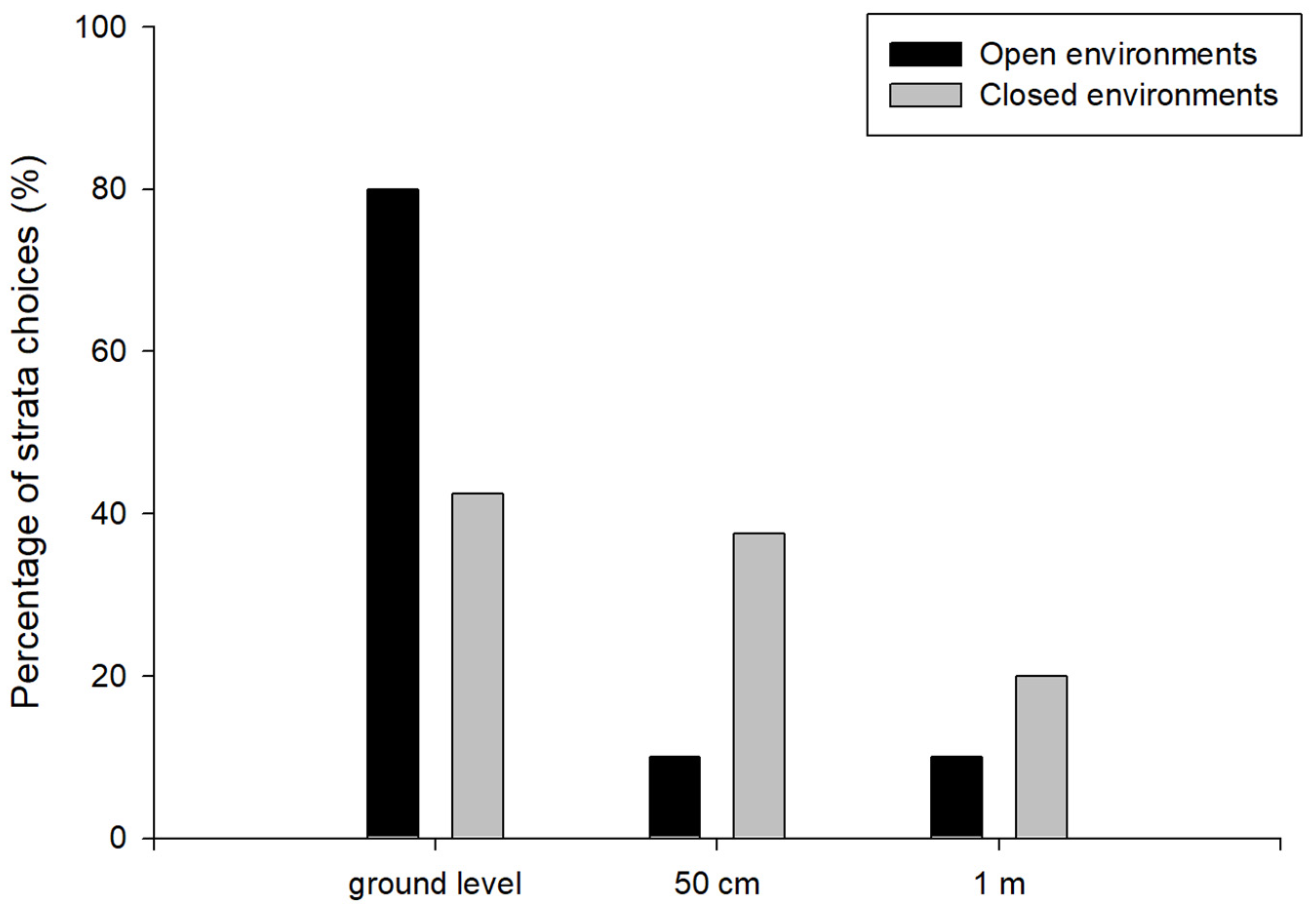

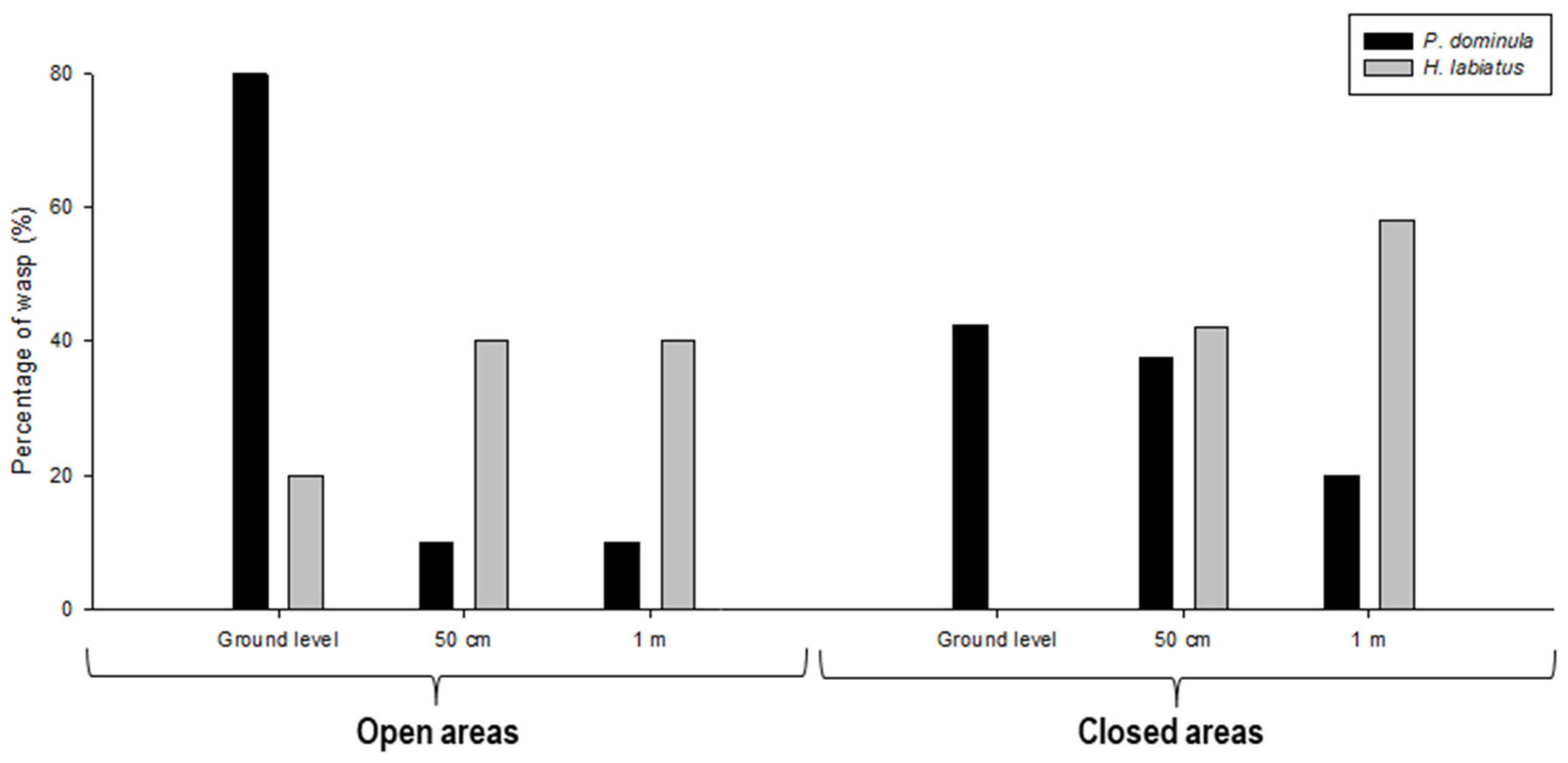

3.1. Experiment 1

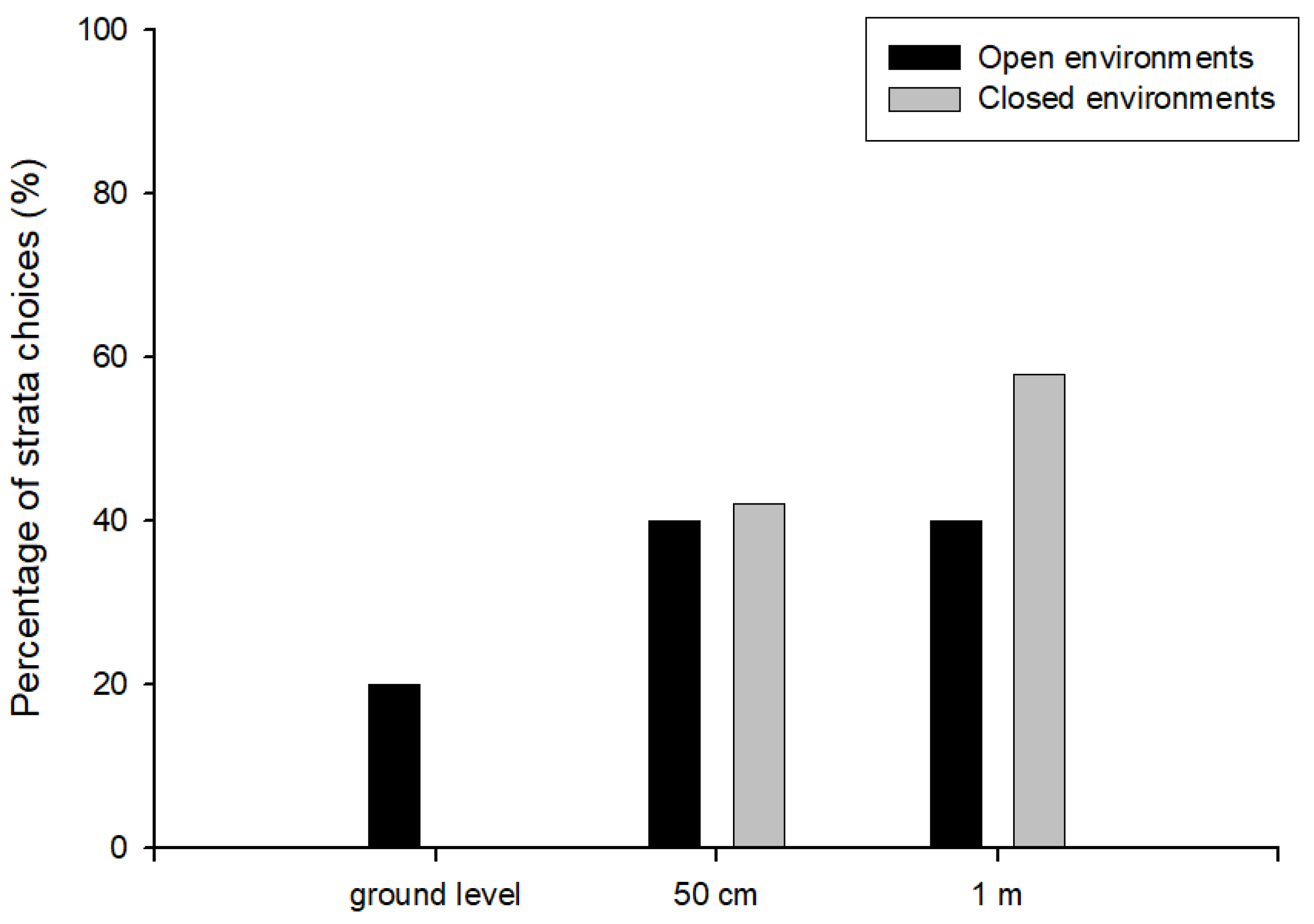

3.2. Experiment 2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackburn, T.M.; Pyšek, P.; Bacher, S.; Carlton, J.T.; Duncan, R.P.; Jarošík, V.; Wilson, J.R.U.; Richardson, D.M. A proposed unified framework for biological invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, J.L.; Hoopes, M.F.; Marchetti, M.P. Invasion Ecology; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.B.; Back, M.; Crowell, M.D.; Farooq, N.; Ghimire, P.; Obarein, O.A.; Smart, K.E.; Taucher, T.; VanderJeugdt, E.; Perry, K.I.; et al. Coexistence between similar invaders: The case of two cosmopolitan exotic insects. Ecology 2023, 104, e3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebens, H.; Blackburn, T.M.; Dyer, E.E.; Genovesi, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Jeschke, J.M.; Pagad, S.; Pyšek, P.; Winter, M.; Arianoutsou, M.; et al. No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhold, A.M.; MacDonald, W.L.; Bergdahl, D.; Mastro, V.C. Invasion by exotic forest pests: A threat to forest ecosystems. Forest Sci. 1995, 41, a0001–z0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, P.J.; Beggs, J.R. Invasion success and management strategies for social vespula wasps. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.M.; Potter, D.A. Invasive paper wasp turns urban pollinator gardens into ecological traps for monarch butterfly larvae. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreyra, S.; Lozada, M. How behavioral plasticity enables foraging under changing environmental conditions in the social wasp Vespula germanica (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Insect Sci. 2020, 28, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreyra, S.; Lozada, M. Polistes dominula spatial learning abilities while foraging. Ethology 2024, 130, e13505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, M.; Bergman, M.; Kullberg, J.; Wahlberg, N.; Wiklund, C. Niche separation in space and time between two sympatric sister species—A case of ecological pleiotropy. Evol. Ecol. 2008, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Nie, P.; Hu, X.; Feng, J. Future range expansions of invasive wasps suggest their increasing impacts on global apiculture. Insects 2024, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Hera, O.; Alonso, M.L.; Alonso, R.M. Behaviour of Vespa velutina nigrithorax (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) under Controlled Environmental Conditions. Insects 2023, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.R. Social wasp (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) foraging behavior. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2000, 45, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, F.B.; da Silva, M.; Soleman, R.A.; Lopes, R.B.; Grandinete, Y.C.; Almeida, E.A.B.; Wenzel, J.W.; Carpenter, J.M. Marimbondos: Systematics, biogeography, and evolution of social behaviour of neotropical swarm-founding wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Epiponini). Cladistics 2021, 37, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackmann, P.; Villacide, J.M.; Corley, J. Presencia de una nueva avispa social exótica, Polistes dominulus (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) en la Patagonia argentina. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 2003, 62, 72–73. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0373-56802003000100011 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Beggs, J.R.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Corley, J.C.; Kenis, M.; Masciocchi, M.; Muller, F.; Rome, Q.; Villemant, C. Ecological effects and management of invasive alien Vespidae. BioControl 2011, 56, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, F.; Benadé, P.C.; Samways, M.J.; Veldtman, R. Better colony performance, not natural enemy release, explains numerical dominance of the exotic Polistes dominula wasp over a native congener in South Africa. Biol. Invasions 2019, 21, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howse, M.W.F.; Haywood, J.; Lester, P.J. Bioclimatic modelling identifies suitable habitat for the establishment of the invasive european paper wasp (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) across the southern hemisphere. Insects 2020, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGruddy, R.; Howse, M.W.F.; Haywood, J.; Toft, R.J.; Lester, P.J. Nesting ecology and colony survival of two invasive Polistes wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in New Zealand. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 50, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranshaw, W.S.; Larsen, H.J.; Zimmerman, R.J. Notes on fruit damage by the European paper wasp, Polistes dominula (Christ) (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Southwest. Entomol. 2011, 36, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, S.; Cini, A. Paper wasps (Polistes). In Encyclopedia of Social Insects; Starr, C., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willink, A. Revisión del género Hypodynerus (Hymenoptera. Eumenidae) III. Grupo de H. excipiendus. Acta Zool. Lilloana 1978, 33, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Garcete-Barrett, B.R.; Álvarez, L.J.; Lucia, M. Vespidae. Biodivers. Artróp. Argent. 2023, 6, 503–524. [Google Scholar]

- Lozada, M.; Adamo, P.D.; Buteler, M.; Kuperman, M.N. Social learning in Vespula germanica wasps: Do they use collective foraging strategies? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finke, D.L.; Snyder, W.E. Niche partitioning increases resource exploitation by diverse communities. Science 2008, 321, 1488–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, G.; Calenge, C.; Loison, A.; Jullien, J.M.; Maillard, D.; Lopez, J.F. Spatial distribution and habitat selection in coexisting species of mountain ungulates. Ecography 2012, 35, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, J.A.; Velasco, J.; Millán, A.; Green, A.J.; Coccia, C.; Guareschi, S.; Gutiérrez-Cánovas, C. Biological invasion modifies the co-occurrence patterns of insects along a stress gradient. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 1957–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.J.; Thomas, C.D.; Moller, H. The influence of habitat use and foraging on the replacement of one introduced wasp species by another in New Zealand. Ecol. Entomol. 1991, 16, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Gao, G.; Ali, A.; Lu, Z. Settling preference of two coexisting aphid species on the adaxial and abaxial surfaces of walnut leaves. Environ. Entomol. 2022, 51, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervo, R.; Zacchi, F.; Turillazzi, S. Polistes dominulus (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) invading North America: Some hypotheses for its rapid spread. Insectes Soc. 2000, 47, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, K.M.; Wenzel, J.W. High Productivity in Haplometrotic Colonies of the Introduced Paper Wasp Polistes dominulus (Hymenoptera: Vespidae; Polistinae). J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 2000, 108, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, F.; Grozinger, C.M.; Beani, L. Examining the “evolution of increased competitive ability” hypothesis in response to parasites and pathogens in the invasive paper wasp Polistes dominula. Naturwissenschaften 2013, 100, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benade, P.C. Invaded Range and Competitive Ability of the Newly Invasive Polistes dominula Compared to that of Its Native Congener Species in the Western Cape, South Africa. Master’s Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Telleria, M.C. Plant resources foraged by Polybia scutellaris (hym. Vespidae) in the argentine pampas. Grana 1996, 35, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, P.; Lozada, M. Cognitive plasticity in foraging Vespula germanica wasps. J. Insect Sci. 2011, 11, 10301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozada, M.; D’Adamo, P. Learning in an exotic social wasp while relocating a food source. J. Physiol. Paris 2014, 108, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreyra, S.; D’Adamo, P.; Lozada, M. Cognitive processes in Vespula germanica wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) when relocating a food source. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2012, 105, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreyra, S.; Lozada, M. Spatial configuration learning in Vespula germanica forager wasps. Ethology 2022, 128, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreyra, S.; Lozada, M. Invasive social wasp learning abilities when foraging in human modified environments. Behav. Process. 2025, 228, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moreyra, S.; Lozada, M. Foraging Patterns of Two Sympatric Wasp Species: The Worldwide Invasive Polistes dominula and the Native Hypodynerus labiatus. Insects 2026, 17, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010038

Moreyra S, Lozada M. Foraging Patterns of Two Sympatric Wasp Species: The Worldwide Invasive Polistes dominula and the Native Hypodynerus labiatus. Insects. 2026; 17(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreyra, Sabrina, and Mariana Lozada. 2026. "Foraging Patterns of Two Sympatric Wasp Species: The Worldwide Invasive Polistes dominula and the Native Hypodynerus labiatus" Insects 17, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010038

APA StyleMoreyra, S., & Lozada, M. (2026). Foraging Patterns of Two Sympatric Wasp Species: The Worldwide Invasive Polistes dominula and the Native Hypodynerus labiatus. Insects, 17(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010038