Biological Characteristics and Rearing Techniques for Vespid Wasps with Emphasis on Vespa mandarinia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biological Characteristics of Vespid Wasps

2.1. Classification and Distribution

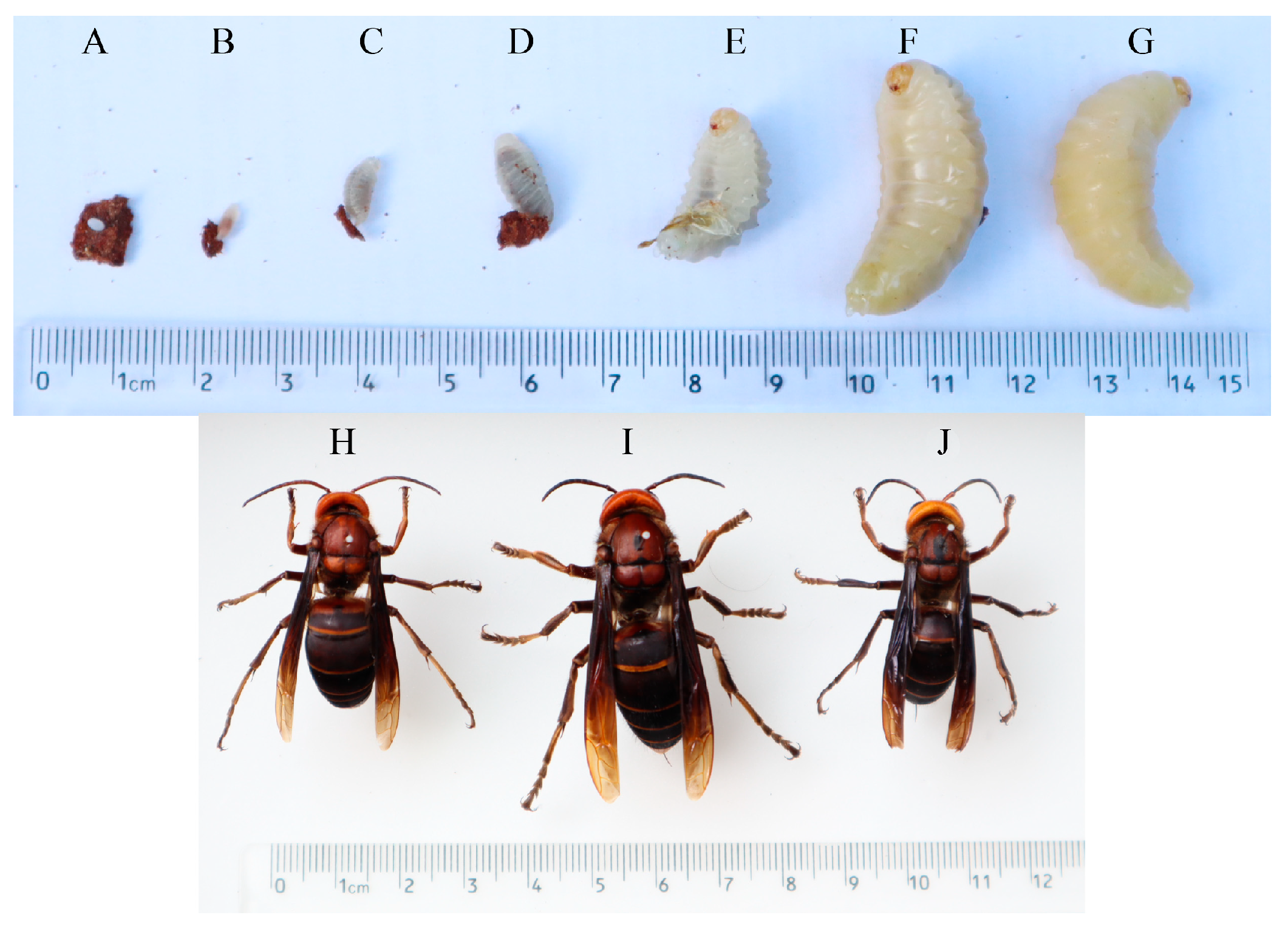

2.2. Morphological Characteristics

2.3. Live Habits

2.3.1. Social Organization and Its Rearing Implications

2.3.2. Nesting Behavior and Artificial Nest Design

2.3.3. Predatory Behavior and Feeding Management

2.3.4. Reproductive Cycle and Colony Population Control

2.3.5. Characteristics of V. mandarinia

3. Rearing Technology of V. mandarinia

3.1. Pre-Rearing Preparations

3.1.1. Site Selection

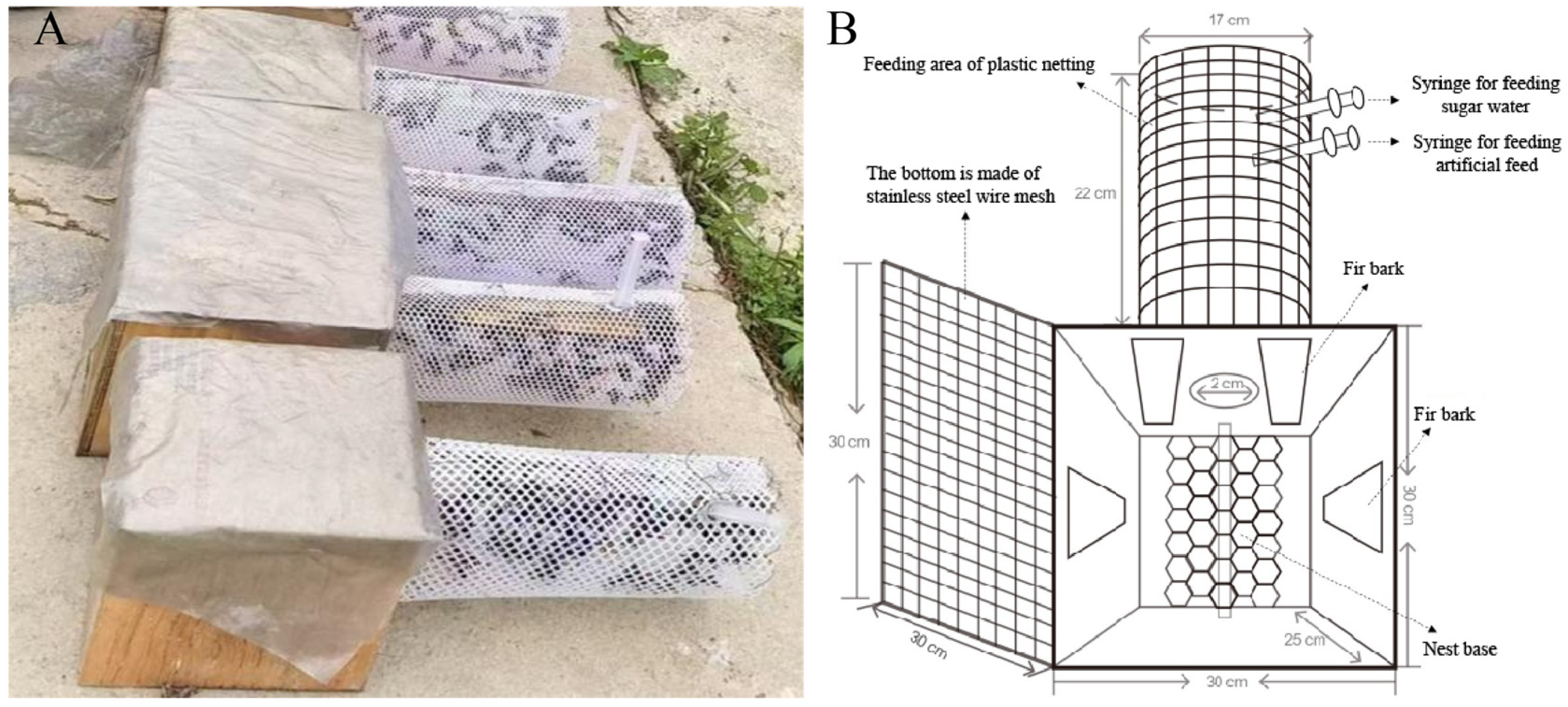

3.1.2. Main Rearing Facilities and Equipment

3.2. Rearing Technology and Management

3.2.1. The Acquisition of Prospective Queen Wasps

3.2.2. Mating Period Management

3.2.3. Management During the Expansion Period of Small Wasp Colonies

3.2.4. Field Rearing Management

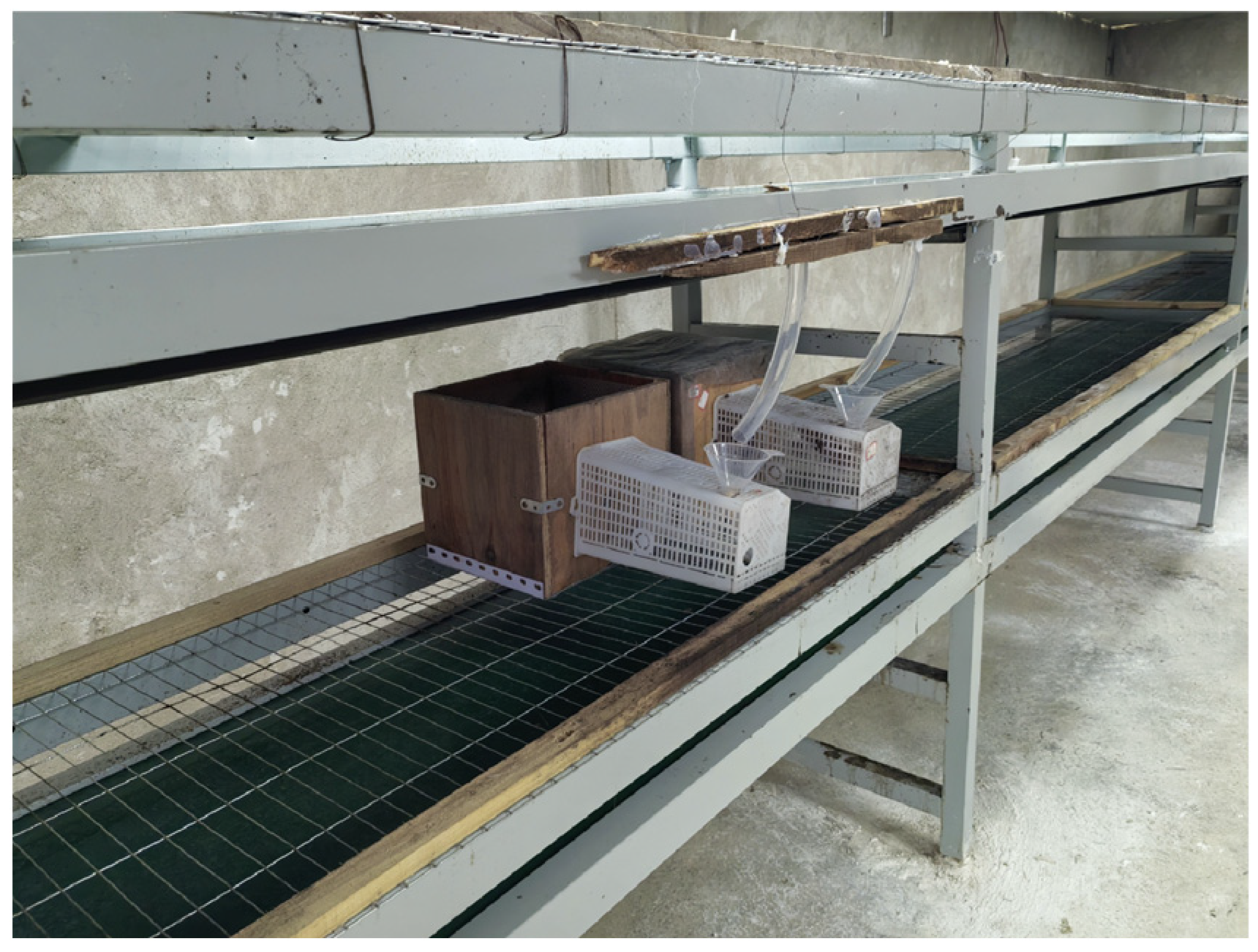

3.2.5. Year-Round Indoor Rearing

3.3. Feed Production Technology

3.3.1. Artificial Feed

3.3.2. Natural Feed

4. Natural Enemies and Pest Control of Wasps

4.1. Main Natural Enemies of Wasps

4.2. Main Pests and Diseases of Wasps

4.3. Integrated Control Methods

4.3.1. Pest, Disease Quarantine, and Chemical Control

4.3.2. Breeding of Disease-Resistant Wasp Strains

4.3.3. Management Techniques for Prevention

5. Product Harvesting, Processing, and Storage

6. Composition, Extraction, and Application of Wasp Venom

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, S.Z. Compendium of Materia Medica, 1st ed.; Shanxi Science and Technology Press: Taiyuan, China, 2014; p. 1006. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.F.; Wang, P. Rheumatism-relieving wasp wine. Apic. China 2020, 71, 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (Volume I), 12th ed.; China Medical Science Press: Beijing, China, 2025; p. 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.H. Study on the Quality Control Method and Biological Activity of Venom from Vespa bicolor Fabricius. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Guangzhou, China, 2022; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.K. Protein Composition Analysis and Functions of Four Bee Venoms. Master’s Thesis, Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin, China, 2019; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, T.; Zhong, C.; Li, M. Analysis of resource value and breeding status of wasps. Chin. J. Ethnomed. Ethnopharm. 2023, 32, 49–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Itterbeeck, J.V.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, C.; Tan, K.; Saga, T.; Nonaka, K.; Jung, C. Rearing techniques for hornets with emphasis on Vespa velutina (Hymenoptera: Vespidae): A review. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 2021, 24, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, G.; Kumar, P.G. New records of potter wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Eumeninae) from Arunachal Pradesh, India: Five genera and ten species. J. Threat. Taxa. 2010, 2, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Yang, X. Analytic research on inorganic elements in Vespa mandarinia smith. Chin. J. Ethnomed. Ethnopharm. 2021, 30, 31–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.Z.; Chen, Q.Y.; He, A.; Shen, L.Y. Construction of high-quality development system of wasp breeding industry. North. Anim. Husb. 2024, 17. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7111576118 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Dong, D.Z.; Wang, Y.Z.; Le, Y.G. Evaluation of the benefit vs. harm relationship of social wasps. J. Southwest Agric. Univ. 2000, 5, 441–442+447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Y.; Duan, Y. Efficient Rearing and Utilization Techniques of Wasps/Hornets, 3rd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Requier, F.; Rome, Q.; Chiron, G.; Decante, D.; Marion, S.; Menard, M.; Muller, F.; Villemant, C.; Henry, M. Predation of the invasive Asian hornet affects foraging activity and survival probability of honey bees in Western Europe. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.H.; Lin, Z.G.; Zheng, H.Q.; Hu, F.L. Wasps from the beekeeper’s perspective. Apic. China 2014, 65, 20–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Jung, C. Study on defensive behavioral mechanism of Vespa hornets by anthropogenic external disturbance. J. Apic. 2019, 34, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Ye, Y.; Xie, J.; Zhang, Z. Adavances in the pathogenesis of bee sting. J. Hainan Med. 2018, 29, 2940–2942. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Perrard, A.; Haxaire, J.; Rortais, A.; Villemant, C. Observations on the colony activity of the Asian hornet Vespa velutina Lepeletier 1836 (Hymenoptera: Vespidae: Vespinae) in France. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 2009, 45, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.J.; Yi, C.H.; Zhang, Z.W.; Ren, X.P.; Lin, Z.Y. The status and problems of wasps artificial breeding. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2018, 57, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Y. Study on wasp breeding technique and popularization. Guangdong Seric. 2024, 58, 50–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.E. Taxonomy, distribution and nesting biology of species of the genera Provespa Ashmead and Vespa Linnaeus (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Entomol. Mon. Mag. 2008, 144, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, P.E.; Gauld, I.D. The Hymenoptera of Costa Rica, 1st ed.; Oxford Science Publications: Oxford, UK, 1995; p. 587. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Li, T.G.; Chen, B. The taxonomic research progress of Eumeninae (Hymenoptera:Vespidae). J. Chongqing Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2011, 28, 8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.L.; Van Achterberg, K.; Duan, M.J.; Chen, X.X. An illustrated key to the species of subgenus Gyrostoma Kirby, 1828 (Hymenoptera, Vespidae, Polistinae) from China, with discovery of Polistes (Gyrostoma) tenuispunctia Kim, 2001. Zootaxa 2014, 3785, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, M.; Yamane, S. Biology of the Vespine Wasps, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.J. Colour Atlas of Chinese Vespid Wasps, 1st ed.; Henan Science and Technology Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2023; p. 622. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.L.; Fang, H.T. Research progress of Vespidae in China. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2008, 36, 3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Wu, X.G. Design of an anti-theft detection system for wasp rearing based on LoRa. Internet Things Technol. 2023, 13, 20–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. On the dissection and observation of the nest of Vespa bicolor. J. Ningde Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2003, 15, 353–355. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Q.D. Reserch on the Biological Characteristics and Epicuticular Hydrocarbona of the Vespa veiutina. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2024; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Sabrina, M.; D’Adamo, P.; Lozada, M. The influence of past experience on wasp choice related to foraging behavior. Insect Sci. 2014, 21, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.R.; Dyer, A.G. Quantity misperception by hymenopteran insects observing the solitaire illusion. iScience 2024, 27, 108697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M.E.; Penney, D. Vespine Wasps of the World: Behaviour, Ecology & Taxonomy of the Vespinae, 1st ed.; Siri Scientific Press: Castleton, UK, 2012; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, M.J.; Franklin, D.N.; Datta, S.; Brown, M.A.; Budge, G.E. Predicting the spread of the Asian hornet (Vespa velutina) following its incursion into Great Britain. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.Z.; Wang, Z.Y. Wasps of Yunnan: Hymenoptera: Vespoidea, 1st ed.; Henan Science and Technology Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2017; p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Chen, D.F. Bee Conservation Science, 2nd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2009; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Z.G. The Living Habits and Control Methods of the Vespa mandarinia. Beekeep. Sci. Technol. 1996, 20. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTExNzE2MDExNxIOUUsxOTk2MDA2MDQyMzgaCDNnYXRyZHp6 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Ai, W.; Yin, H.L.; Chen, H.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Liu, A.B.; Liu, Q. Nutritional component analysis and evaluation of the edible stages of two Vespa species from Baoshan area, Yunnan Province. Biot. Resour. 2023, 45, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Song, Z.Y.; Yang, C.; He, Q.J.; Yi, C.H.; Zhu, E.J. Genetic diversity analysis of domesticated Vespa mandarinia in Yunnan province based on CO I gene marker. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 35, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga, T.; Kanai, M.; Shimada, M.; Okada, Y. Mutual intra- and interspecific social parasitism between parapatric sister species of Vespula wasps. Insectes Soc. 2017, 64, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingliu County Miaoqi Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Formula for Rearing Hornets. China Patent CN109287895A, 1 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xing, C.H.; Liu, J.C. High-protein feed insects—Yellow mealworm breeding technology. Jilin Agric. 2004, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.N.; Zhao, H.R.; Yang, Z.B.; Xu, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, X.M.; Xiao, H. Research progress major toxin components and resource value of wasp. Chin. J. Ethnomed. Ethnopharm. 2017, 26, 68–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.M.; Li, T.S.; Sun, T.M.; Liang, W. Preliminary report on the tumoricidal effect and therapeutic potential of wasp venom. J. Pract. Oncol. 1997, 4, 260–261. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. New advances in pharmacological effects and clinical research of bee venom injection. Gansu Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 123–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Qu, Y.; Lei, X.; Xu, Q.; Li, S.; Shi, Z.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Z. Therapeutic Potential of Bee and Wasp Venom in Anti-Arthritic Treatment: A Review. Toxins 2024, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.K. Protein Composition Analysis and Efficacy Study of Four Bee Venoms. Master’s Thesis, Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin, China, 2020; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, L.L.; Che, Y.H.; Sun, H.M.; Wang, B.; Wang, M.Y.; Yang, Z.Z.; Liu, H.; Xiao, H.; Yang, D.S.; Zhu, H.L.; et al. The Therapeutic Effect of Wasp Venom (Vespa Magnifica, Smith) and Its Effective Part on Rheumatoid Arthritis Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes through Modulating Inflammation, Redox Homeostasis and Ferroptosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 317, 116700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Yu, W.X.; Duan, X.M.; Ni, L.L.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.R.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, C.G.; Yang, Z.B. Wasp Venom Possesses Potential Therapeutic Effect in Experimental Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 6394625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.L. The application history and modern research of bee venom. Era Educ. 2015, 35. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=mg_qcPBBapmmqCQOk6DZ5m6FRknHRTv2VdQHAKyUMhY4DPsMpqcUKL-thwmOCybPOI76JOv0CPQiYzHcVS2RHMb9cxLie9of5yyhFY5TGjqLSBtX7iSIpHEpPyVt_SubTYLC5AY0gS2kZq0U9tK0iyjUX0y3yl3tWc9PBNGTI9kt5DLbXGZ4aFxDbq-lgNWl&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Zhang, B.Q.; Liu, X.B. Research progress on the main components and pharmacological effects of bee venom. Pharm. Res. 2016, 35, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Yao, L.; Xiao, L. Research progress on pharmacological effects of bee venom peptides. Chin. Folk. Ther. 2020, 28, 112–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.C.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X.; Xie, X.H.; Jiang, X.F.; Zhu, W.H. Research progress on the anti-tumor mechanism of bee venom peptide. J. Jilin Med. Coll. 2018, 39, 462–464. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yousefpoor, Y.; Amiani, A.; Divsalar, A.; Mousaviet, S.E.; Skakeri, A.; Sabzevari, J.T. Anti-rheumatic activity of topical nanoemulsion containing bee venom in rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2022, 172, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J. Promoting scientific breeding techniques to ensure the sustainable use of wasp resources. Sci. Technol. Innov. Her. 2012, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.Z.; Dai, Z.Y.; Liang, Z.L. Preliminary study on indoor rearing of wasps. Jiangxi J. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2024, 51–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Van Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security, 1st ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.X.; Xie, Z.H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.M.; Jiang, X.J.; Jia, Y.K. The Current Status, Opportunity and Challendge of Hornet Keeping in China. Mod. Agric. Res. 2025, 31, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J.; Wang, J.A.; Tao, S.B. Present situation and prospect of wasp resource industry. Mod. Agric. Res. 2018, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparison Dimension | Field Rearing | Indoor Artificial Rearing |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental control | Relies on natural climate; largely uncontrollable | Precise control over temperature, humidity, and photoperiod |

| Initial investment | Relatively low | Relatively high (requires construction/leasing of facilities and equipment) |

| Labor input | Relatively low, with extensive management | Relatively high, requiring intensive management |

| Impact of climate/predators | Significant (typhoons, drought, predators) | Minimal, due to environmental isolation |

| Queen oviposition period | Limited by natural seasonal cycles | Can be extended via environmental manipulation, enabling year-round production |

| Disease/pest risk | Higher risk due to increased interaction with the wild environment | Isolated environment allows for controlled risk |

| Product quality | Perceived as closer to wild; often higher market acceptance | Requires careful nutritional balance to prevent quality decline due to homogeneous environment |

| Suitable application | Suitable for initial colonization and population expansion | Suitable for large-scale production |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, L.; Du, J.; Wei, G.; Tian, Y.; Li, S. Biological Characteristics and Rearing Techniques for Vespid Wasps with Emphasis on Vespa mandarinia. Insects 2025, 16, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121231

Lv L, Du J, Wei G, Tian Y, Li S. Biological Characteristics and Rearing Techniques for Vespid Wasps with Emphasis on Vespa mandarinia. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121231

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Lijuan, Juan Du, Guoliang Wei, Yu Tian, and Shangwei Li. 2025. "Biological Characteristics and Rearing Techniques for Vespid Wasps with Emphasis on Vespa mandarinia" Insects 16, no. 12: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121231

APA StyleLv, L., Du, J., Wei, G., Tian, Y., & Li, S. (2025). Biological Characteristics and Rearing Techniques for Vespid Wasps with Emphasis on Vespa mandarinia. Insects, 16(12), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121231