Infestation, Community Structure, and Seasonal Dynamics of Chiggers on Small Mammals at a Focus of Scrub Typhus in Northern Yunnan, Southwest China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

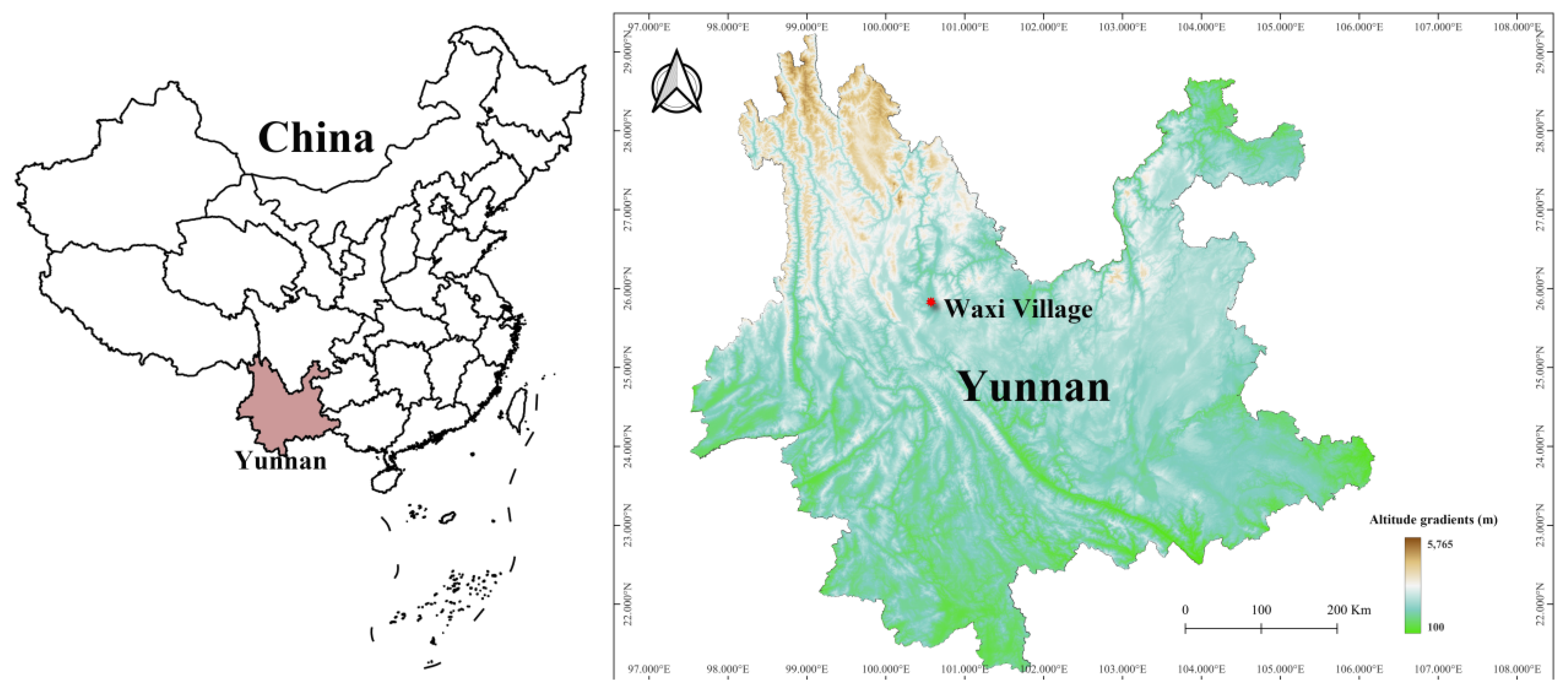

2.1. Field Investigations

2.2. Collection of Animal Hosts and Chiggers

2.3. Specimen-Making and Taxonomic Identification of Chiggers

2.4. Basic Statistics of Chigger Infestation and Community

2.5. Analysis of Species Abundance and Species-Sample Relationship

2.6. Analysis of Chigger-Host and Chigger-Chigger Relationship

2.7. Analysis on Seasonal Dynamics of Chigger Community

3. Results

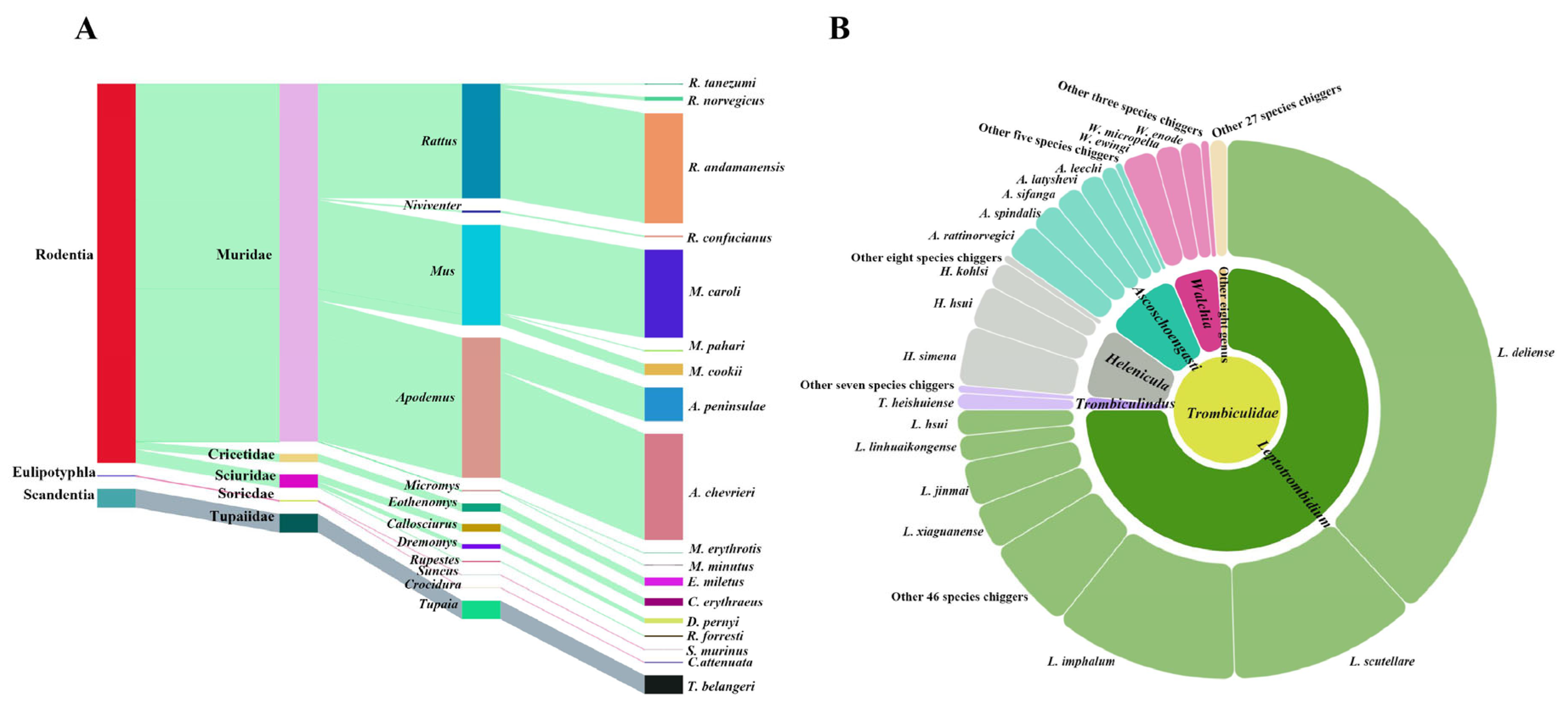

3.1. Species Composition of Small Mammal Hosts and Chiggers

3.2. Infestation of Vector Chiggers

3.3. Infestation and Community Indexes of Chiggers on Main Hosts

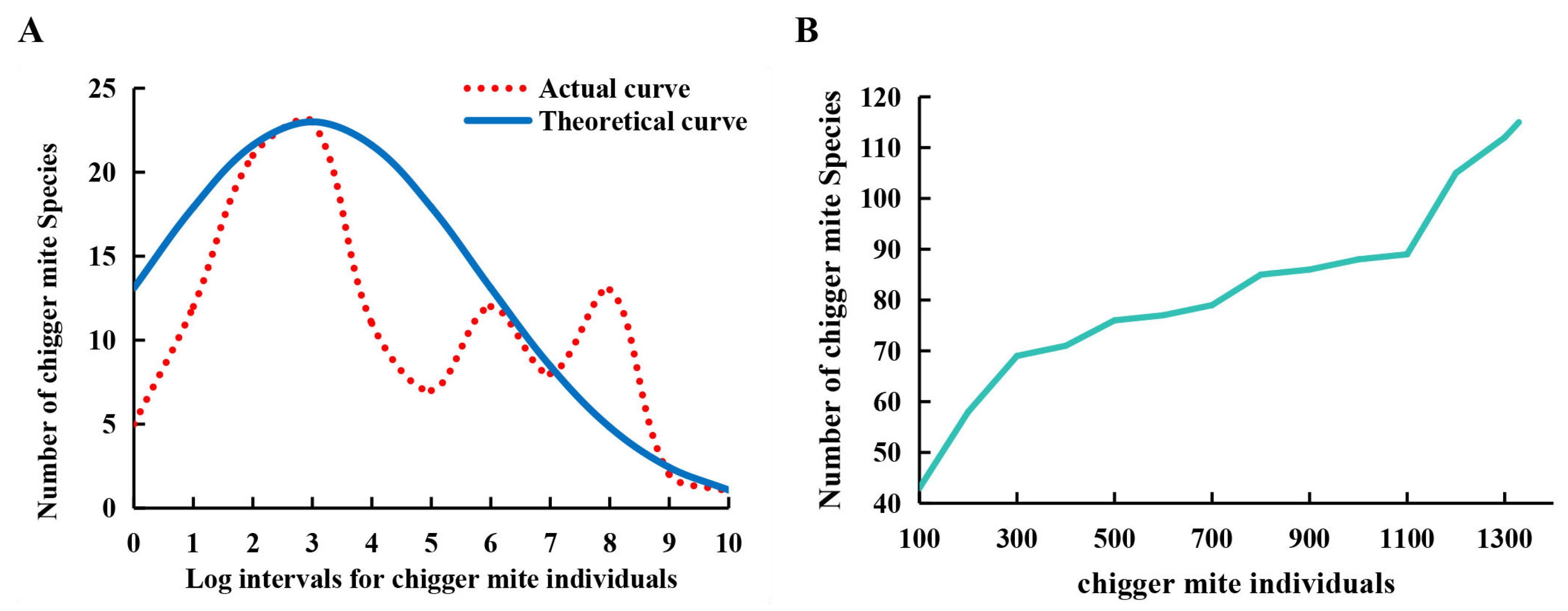

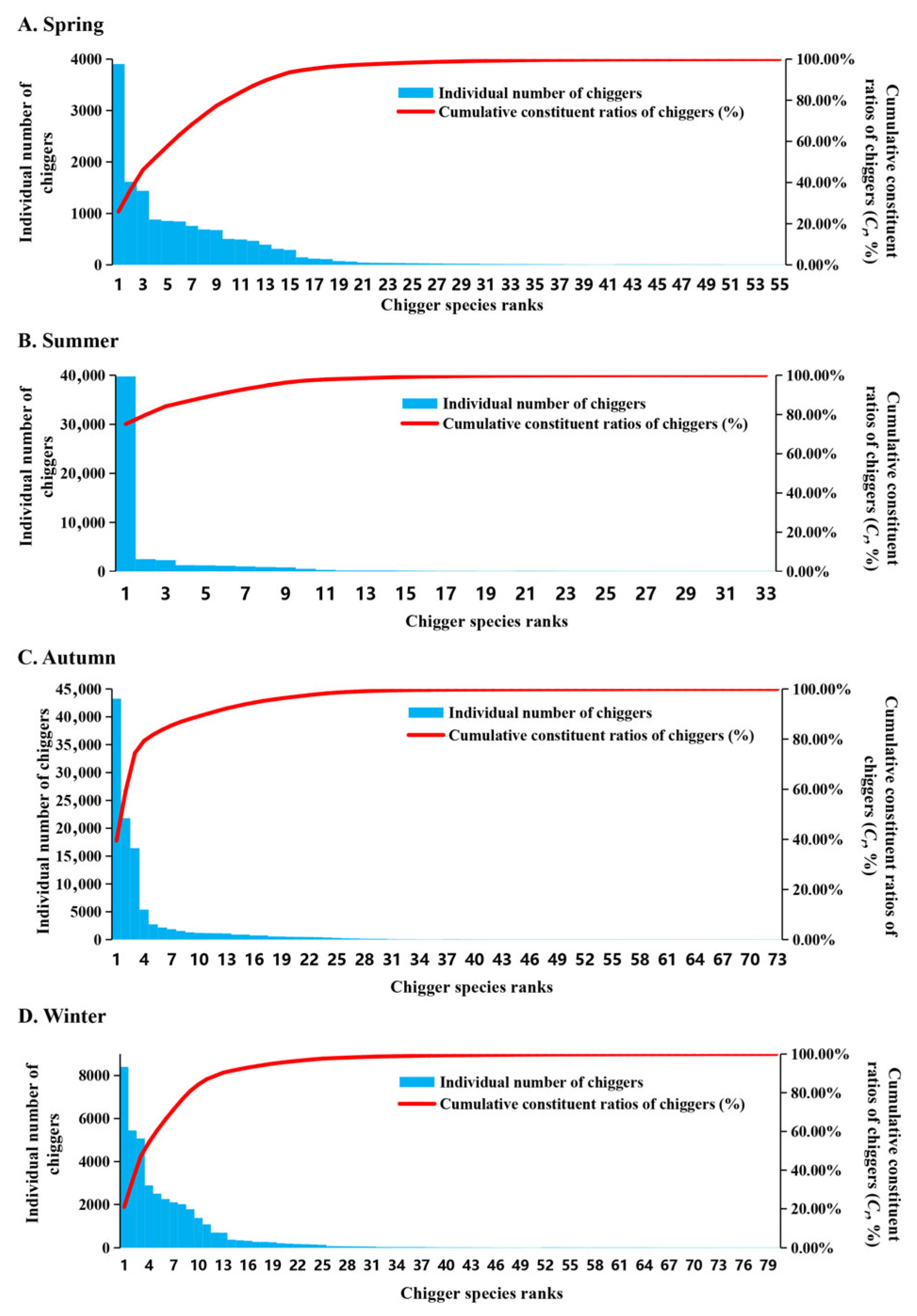

3.4. Species Abundance Distribution and Species-Sample Relationship

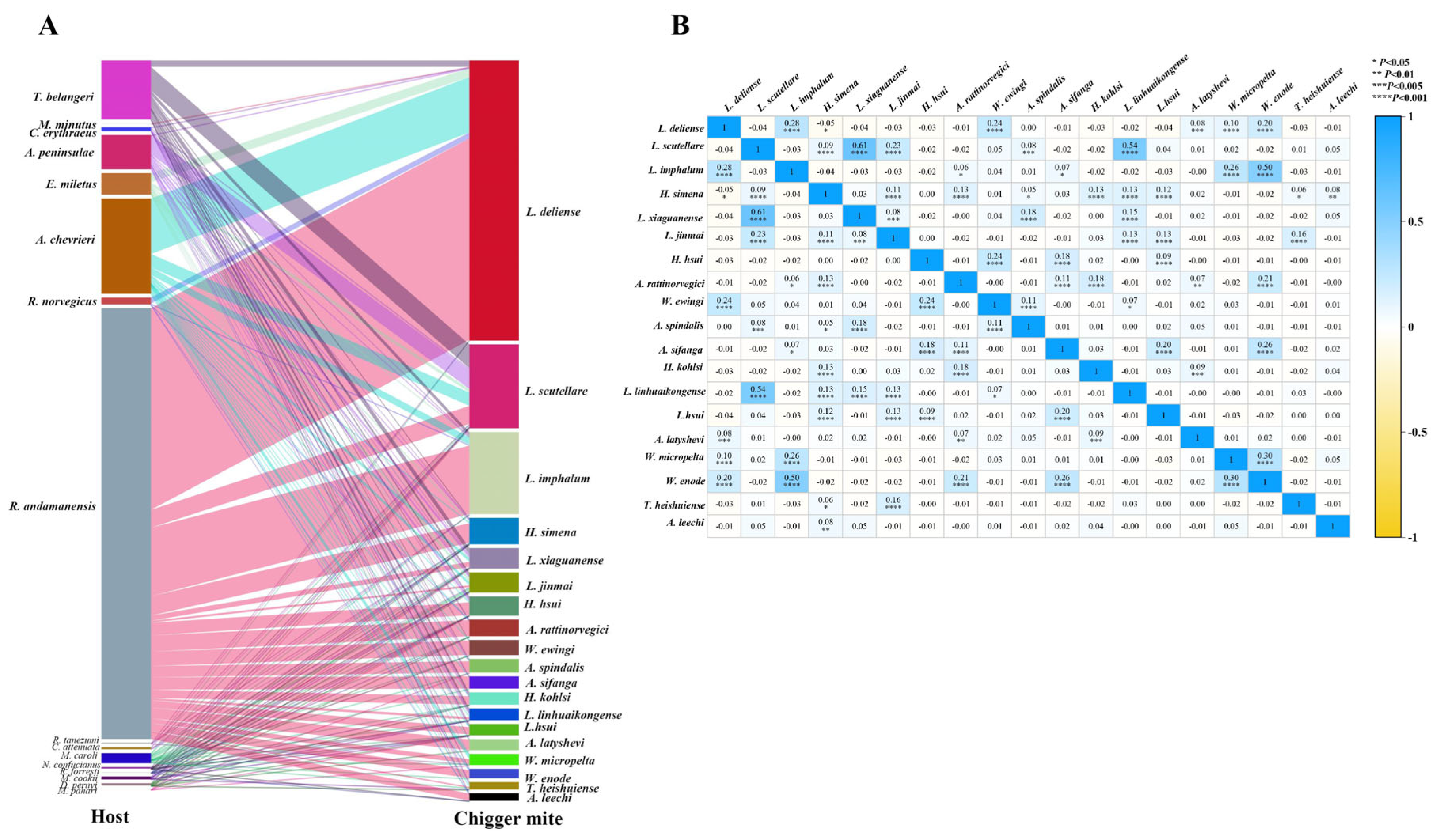

3.5. Chigger-Host and Chigger-Chigger Relationship

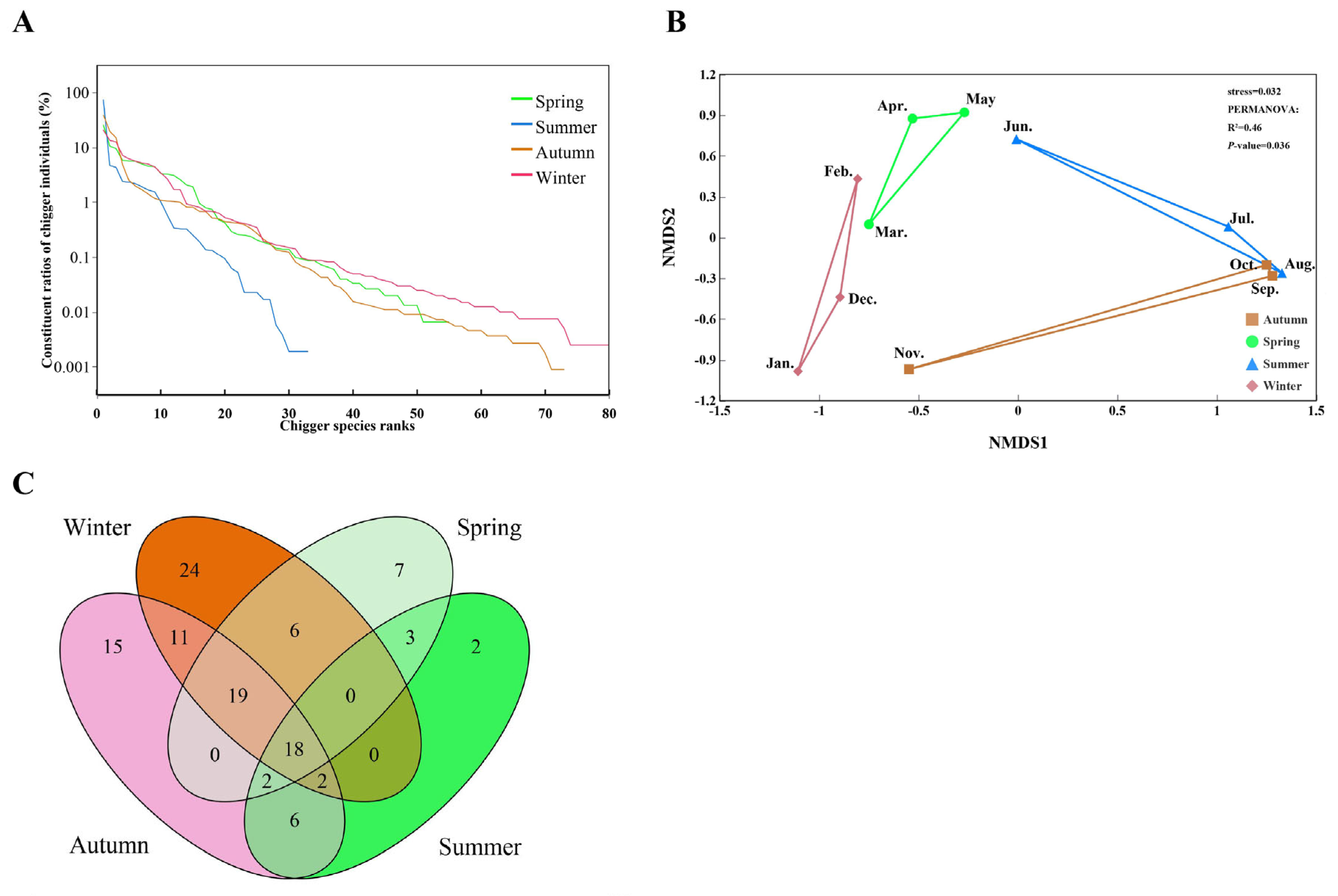

3.6. Seasonal Dynamics of Chigger Infestation and Community

4. Discussion

4.1. Medical Significance of the Chigger Study

4.2. Infestation and Coexistence of Multiple Vector Chiggers

4.3. Species Abundance and Species-Sample Relationship

4.4. Host-Chigger and Chigger-Chigger Relationships

4.5. Seasonal Fluctuation of Chigger Infestation and Community

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hardgrove, E.; Zimmerman, D.M.; Fricken, M.E.V.; Deem, S. A scoping review of rodent-borne pathogen presence, exposure, and transmission at zoological institutions. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 193, 105345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahmana, H.; Granjon, L.; Diagne, C.; Davoust, B.; Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O. Rodents as hosts of pathogens and related zoonotic disease risk. Pathogens 2020, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, J.X.; Guo, X.G.; Song, W.Y.; Zhao, C.F.; Zhang, Z.W.; Fan, R.; Chen, T.; Lv, Y.; Yin, P.W. Species diversity and related ecology of chiggers on small mammals in a unique geographical area of Yunnan Province, southwest China. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2023, 91, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santibáñez, P.; Palomar, A.M.; Portillo, A.; Santibáñez, S.; Oteo, J.A. The role of chiggers as human pathogens. In An Overview of Tropical Diseases; In TechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2015; pp. 173–202. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P.Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C.; Dong, W.G.; Qian, T.J.; Qin, F.; Yang, Z.H.; Fan, R. Landscapes with different biodiversity influence distribution of small mammals and their ectoparasitic chigger mites: A comparative study from southwest China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e189987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Wang, D.Q.; Chen, X.B. Trombiculid Mites of China: Studies on Vector and Pathogen of Tsutsugamushi Disease; Guangdong Science and Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 1997; pp. 1–570. [Google Scholar]

- Derne, B.; Weinstein, P.; Musso, D.; Lau, C. Distribution of rickettsioses in Oceania: Past patterns and implications for the future. Acta Trop. 2015, 143, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.J.; Guo, X.G.; Zhao, C.F.; Zhao, Y.F.; Peng, P.Y.; Jin, D.C. An ecological survey of chiggers (Acariformes: Trombiculidae) associated with small mammals in an epidemic focus of scrub typhus on the China-Myanmar border in southwest China. Insects 2024, 15, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, R.; Guo, X. Research advances of Leptotrombidium scutellare in China. Korean J. Parasitol. 2021, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, I.; Pearson, I.; Dahal, P.; Thomas, N.V.; Roberts, T.; Newton, P.N. Scrub typhus ecology: A systematic review of Orientia in vectors and hosts. Parasit. Vector. 2019, 12, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, Q.; Han, L.; Shi, Y.; Geng, M.J.; Teng, Z.Q.; Kan, B.; Mu, D.; Qin, T. Epidemiological study of scrub typhus in China, 2006–2023. Dis. Surveill. 2024, 39, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P.Y.; Duan, H.; Xu, L.Y.; Zhang, L.T.; Sun, J.Q.; Zu, Y.; Ma, L.J.; Sun, Y.; Yan, T.L.; Guo, X.G. Epidemiologic changes of a longitudinal surveillance study spanning 51 years of scrub typhus in mainland China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.H.; Chen, M.; Yang, X.D. Epidemiological analysis of scrub typhus in Yunnan Province during 2006–2017. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control 2018, 29, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.G.; Qian, T.J.; Meng, X.Y.; Dong, W.G.; Shi, W.X.; Wu, D. Preliminary analysis of chigger communities associated with house rats (Rattus flavipectus) from six counties in Yunnan, China. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2006, 11, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannar Martin, K.H.; Kremer, C.T.; Ernest, S.K.M.; Leibold, M.A.; Auge, H.; Chase, J.; Declerck, S.A.J.; Eisenhauer, N.; Harpole, S.; Hillebrand, H.; et al. Integrating community assembly and biodiversity to better understand ecosystem function: The community assembly and the functioning of ecosystems (CAFE) approach. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Yang, W.H.; Feng, Y. Epidemiological characteristics of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Yunnan Province, China, 2012–2020. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control 2021, 32, 715–719. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.H.; Feng, X.G.; Mi, Z.Q.; Zhang, H.L.; Zi, D.Y.; Chen, Y.M. Investigation on the outbreak of tsutsugamushi disease in Binchuan County, Yunnan Province. Chin. J. Zoon. 1999, 15, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.W. Analysis on the characteristics of rainfall time variation in Binchuan County, Yunnan Province. Shaanxi Water Resour. 2020, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C.; Song, W.Y.; Fan, R.; Zhao, C.F.; Zhang, Z.W.; Mao, K.Y.; Peng, P.Y.; Lin, H.; et al. Host selection and seasonal fluctuation of Leptotrombidium deliense (Walch, 1922) (Trombidiformes: Trombiculidae) at a localized area of southern Yunnan, China. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2019, 24, 2253–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C.; Dong, W.G.; Qian, T.J.; Qin, F.; Yang, Z.H. Species abundance distribution and ecological niches of chigger mites on small mammals in Yunnan Province, southwest China. Biologia 2017, 72, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, E.; Moghddas-Sani, H.; Hassanpoor, H.; Vatandoost, H.; Zahabiun, F.; Akhavan, A.; Hanafi-Bojd, A.; Telmadarraiy, Z. Ectoparasites of rodents captured in Bandar Abbas, southern Iran. Iran. J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2009, 3, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X. A Complete Checklist of Mammal Species and Subspecies in China, a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 1–394. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; pp. 1–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Gill, B.; Song, B.G.; Chu, H.; Park, W.I.; Lee, H.I.; Shin, E.; Cho, S.; Roh, J.Y. Annual fluctuation in chigger mite populations and Orientia tsutsugamushi infections in scrub typhus endemic regions of south Korea. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2019, 10, 351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.G.; Speakman, J.R.; Dong, W.G.; Men, X.Y.; Qian, T.J.; Wu, D.; Qin, F.; Song, W.Y. Ectoparasitic insects and mites on Yunnan red-backed voles (Eothenomys miletus) from a localized area in southwest China. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 3543–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekolnikov, A.A. Leptotrombidium (Acari: Trombiculidae) of the world. Zootaxa 2013, 3728, 1–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercammen-Grandjean, P.H.; Langston, R. The Chigger Mites of the World (Acarina: Trombiculidae & Leeuwenhoekiidae). Volume III. Leptotrombidium Complex; George Williams Hooper Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1976; pp. 1–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. Revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, J. Collecting and preserving ectoparasites for ecological study. In Ecological and Behavioral Methods for the Study of Bats; Kunz, T.H., Ed.; Smithsonian Institute Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P.Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C.; Dong, W.G.; Qian, T.J.; Qin, F.; Yang, Z.H. New record of the scrub typhus vector, Leptotrombidium rubellum, in southwest China. J. Med. Entomol. 2017, 54, 1767–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.Z.; Guo, X.G.; Speakman, J.R.; Zuo, X.H.; Wu, D.; Wang, Q.H.; Yang, Z.H. Abundances and host relationships of chigger mites in Yunnan Province, China. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2013, 27, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.Y.; Guo, X.G.; Song, W.Y.; Hou, P.; Zou, Y.J.; Fan, R. Ectoparasitic chigger mites on large oriental vole (Eothenomys miletus) across southwest, China. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, U.J.; Mohanty, S.; Mahapatra, A.S.; Mondal, H.K.; Samanta, M.; Maiti, N.K. Exploring the gut microbiota composition of Indian major carp, rohu (Labeo rohita), under diverse culture conditions. Genomics 2022, 114, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæther, B.E.; Engen, S.; Grøtan, V. Species diversity and community similarity in fluctuating environments: Parametric approaches using species abundance distributions. J. Anim. Ecol. 2013, 82, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.Q.; Das, S.; Chaudhary, N.; Raju, K. Analysis of the six sigma principle in pre-analytical quality for hematological specimens. Cureus 2023, 15, e42434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C.; Song, W.Y.; Yang, Z.H. Relative abundance of a vector of scrub typhus, Leptotrombidium sialkotense, in southern Yunnan Province, China. Korean J. Parasitol. 2020, 58, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Jiang, Z.K.; Wang, L.; Ding, L.Y.; Mao, C.Q.; Ma, B.Y. Accordance and identification of vector chigger mites of tsutsugamushi disease in China. Chin. J. Hyg. Insect. Equip. 2013, 19, 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.X.; Tian, C.; Yang, X.; Cao, G.; Lv, X.F. Research progress on the distribution of scrub typhus vector chigger mites in China. Chin. J. Hyg. Insect. Equip. 2022, 28, 556–561. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Deng, S.Z.; Ma, T.; Hao, J.X.; Wang, H.; Han, X.; Lu, M.H.; Huang, S.J.; Huang, D.S.; Yang, S.Y. Retrospective analysis of spatiotemporal variation of scrub typhus in Yunnan Province, 2006–2022. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e12654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lv, H.; Zhu, C.; Ai, L.; Qi, Y.; Yue, N.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Tan, W. How meteorological factors impacting on scrub typhus incidences in the main epidemic areas of 10 Provinces, China, 2006–2018. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 992555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsantichon, J.; Jaiyen, Y.; Dittrich, S.; Salje, J. Orientia tsutsugamushi. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Qian, Q.; Magalhaes, R.J.; Han, Z.H.; Haque, U.; Weppelmann, T.A.; Hu, W.B.; Liu, Y.X.; Sun, Y.S.; Zhang, W.Y. Rapid increase in scrub typhus incidence in mainland China, 2006–2014. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 94, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D.H.; Shelite, T.R.; Day, N.P.; Walker, D.H. Unresolved problems related to scrub typhus: A seriously neglected life-threatening disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilak, R.; Kunte, R. Scrub typhus strikes back: Are we ready? Med. J. Armed Forces India 2019, 75, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.Z.; Dong, X.M.; Shen, X.L.; Zhou, Y.M.; Han, Z.M.; Shui, T.J. Epidemiological characteristics of scrub typhus in Yunnan Province, China, 2013–2022. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control 2024, 35, 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.F.; Du, S.S.; Huang, X.X.; Wang, Q.; Li, A.Q.; Li, C.; Sun, L.N.; Wu, W.; Li, H.; Liu, T.Z. Epidemiological characteristics of hemorrhagic fever of renal syndrome in China, 2004–2021. Dis. Surveill. 2023, 38, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P.Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, G.X.; He, W.Y.; Yan, T.L.; Guo, X.G. Epidemiological characteristics and spatiotemporal patterns of scrub typhus in Yunnan Province from 2006 to 2017. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C.; Song, W.Y.; Peng, P.Y.; Lin, H.; Fan, R.; Zhao, C.F.; Zhang, Z.W.; Mao, K.Y.; et al. Infestation and seasonal fluctuation of chigger mites on the southeast Asian house rat (Rattus brunneusculus) in southern Yunnan Province, China. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2021, 14, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, R.; Ren, T.G.; Guo, X.G. Research history and progress of six vector chigger species of scrub typhus in China. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2022, 27, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Fan, R.; Song, W.Y.; Peng, P.Y.; Zhao, Y.F.; Jin, D.C.; Guo, X.G. The distribution and host-association of the vector chigger species Leptotrombidium imphalum in southwest China. Insects 2024, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Guo, X.G.; Jin, D.C. Research progress on Leptotrombidium deliense. Korean J. Parasitol. 2018, 56, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, B.; Yang, Z.Q. Advances in research of tsutsugamushi disease epidemiology in China in recent years. Chin. J. Hyg. Insect. Equip. 2012, 18, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.G.; Dong, W.G.; Men, X.Y.; Qian, T.J.; Fletcher, Q.E. Species abundance distribution of ectoparasites on Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) from a localized area in southwest China. J. Arthropod Borne Dis. 2016, 10, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, C.; Santini, L.; Spake, R.; Bowler, D. Population abundance estimates in conservation and biodiversity research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, M.; Green, D.; Holekamp, K.; Zipkin, E. Integrating distance sampling and presence-only data to estimate species abundance. Ecology 2021, 102, e3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, X.G.; Peng, P.Y.; Lv, Y.; Xiang, R.; Song, W.Y.; Huang, X.B. Infestation and distribution of chiggers on the Anderson’s white-bellied rats in southwest China. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 2920–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.J.; Guo, X.G.; Peng, P.Y.; Lv, Y.; Yin, P.W.; Song, W.Y.; Xiang, R.; Chen, Y.L.; Li, B.; Jin, D.C. Mite infestation on Rattus tanezumi rats in southwest China concerning risk models. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1519188. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, R.; Parajuli, K.; Sherchand, J.B. Epidemiology, risk factors and seasonal variation of scrub typhus fever in central Nepal. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongsiri, M.J.; Roman, J.; Ezenwa, V.O.; Goldberg, T.L.; Koren, H.S.; Newbold, S.C.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Pattanayak, S.K.; Salkeld, D.J. Biodiversity loss affects global disease ecology. BioScience 2009, 59, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzán, G.; Marcé, E.; Giermakowski, J.T.; Mills, J.N.; Ceballos, G.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Armién, B.; Pascale, J.M.; Yates, T.L. Experimental evidence for reduced rodent diversity causing increased Hantavirus prevalence. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Host Species | Individuals of Hosts | Species and Individuals of Chiggers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Cr (%) | Species | Individuals | Cr (%) | |

| Rattus andamanensis | 366 | 27.54 | 83 | 135662 | 62.32 |

| Apodemus chevrieri | 355 | 26.71 | 73 | 31274 | 14.37 |

| Mus caroli | 293 | 22.05 | 38 | 3332 | 1.53 |

| Apodemus peninsulae | 112 | 8.43 | 47 | 11720 | 5.38 |

| Tupaia belangeri | 62 | 4.67 | 50 | 20745 | 9.53 |

| Mus cookii | 38 | 2.86 | 16 | 1043 | 0.48 |

| Eothenomys miletus | 27 | 2.03 | 37 | 7951 | 3.65 |

| Callosciurus erythraeus | 25 | 1.88 | 18 | 1167 | 0.54 |

| Dremomys pernyi | 16 | 1.20 | 17 | 766 | 0.35 |

| Rattus norvegicus | 13 | 0.98 | 13 | 2070 | 0.95 |

| Niviventer confucianus | 6 | 0.45 | 33 | 849 | 0.39 |

| Rupestes forresti | 4 | 0.30 | 10 | 98 | 0.05 |

| Rattus tanezumi | 3 | 0.23 | 7 | 108 | 0.05 |

| Mus pahari | 3 | 0.23 | 7 | 29 | 0.01 |

| Crocidura attenuata | 3 | 0.23 | 10 | 826 | 0.38 |

| Micromys erythrotis | 1 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Micromys minutus | 1 | 0.08 | 1 | 31 | 0.01 |

| Suncus murinus | 1 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Tatal | 1329 | 100.00 | 115 | 217671 | 100.00 |

| Taxonomic Taxa of Chigger Mites | Collected Species and Individuals of Chigger Mites (The Figures Enclosed in Parentheses Are the Collected Individuals for Each Mite Species) |

|---|---|

| Trombiculidae | 217,671 individuals, 115 species, 13 genera, 2 subfamilies |

| Trombiculinae | 204,852 individuals, 92 species, 9 genera |

| Leptotrombidium | Leptotrombidium deliense * (83008), L. scutellare * (24839), L. imphalum * (24313), L. xiaguanense (6098), L. jinmai (5972), L. linhuaikongense * (3474), L. hsui (3339), L. suense (1838), L. eothenomydis (1356), L. densipunctatum (1347), L. shuqui (1109), L. fujianense (1096), L. ejingshanense (880), L. yongshengense (796), L. apodevrieri (635), L. muntiaci (562), L. rubellum * (541), L. baoshui (482), L. gemiticulum (275), L. kunmingense (195), L. chuanxi (174), L. apodemi * (121), L. sinotupaium (114), L. qiui (102), L. rusticum (92), L. gongshanense (82), L. zhongdianense (54), L. qujingense (49), L. yunlingense (33), L. bishanense (28), L. bambicola (24), L. pavlovskyi (22), L. biluoxueshanense (19), L. laxoscutum (16), L. hiemalis (15), L. dianchi (14), L. rupestre (14), L. deplanoscutum (13), L. linji (13), L. shuyui (10), L. yulini (9), L. dichotogalium (8), L. longchuanense (6), L. myotis (6), L. caudatum (6), L. lianghense (6), L. intermedium * (5), L. wangi (5), L. kaohuense * (4), L. sinicum (3), L. alpinum (1), L. taiyuanense (1), L. xishani (1) |

| Trombiculindus | Trombiculindus heishuiense (2226), T. bambusoides (812), T. hunanye (126), T. sanxiaensis (33), T. yunnanus (26), T. nujiange (25), T. hylomydis (5), T. spinifoliatus (1) |

| Muritrombicula | Muritrombicula dali (3) |

| Microtrombicula | Microtrombicula nadchatrami (71) |

| Helenicula | Helenicula simena (7782), H. hsui (5700), H. kohlsi (3639), H. yunnanensis (864), H. litchia (60), H. lanius (35), H. abaensis (22), H. globularis (14), H. rectangia (3), H. miyagawai (3), H. olsufjevi (2) |

| Doloisia | Doloisia taishanensis (6) |

| Cheladonta | Cheladonta micheneri (812), C. ikaoensis (3), C. deqinensis (2) |

| Ascoschoengastia | Ascoschoengastia rattinorvegici (4961), A. spindalis (3993), A. sifanga (3650), A. latyshevi (3287), A. leechi (2218), A. crassiclava (689), A. yunnanensis (205), A. petauristae (16), A. aliena (5), A. yunwui (5) |

| Herpetacarus | Herpetacarus callosciuri (195), H. hastoclavus (64), H. aristoclavus (38), H. fukienensis (26) |

| Gahrliepiinae | 12,819 individuals, 23 species, 4 genera |

| Walchia | Walchia ewingi (4487), W. micropelta (3281), W. enode (2794), W. kor (940), W. sheensis (175), W. pacifica * (1) |

| Schoengastiella | Schoengastiella ligula (44) |

| Gahrliepia | Gahrliepia miyi (909), G. madun (37), G. myriosetosa (31), G. agrariusia (25), G. chekiangensis (18), G. tenuiclava (15), G. octosetosa (12), G. megascuta (10), G. pintanensis (8), G. linguipelta (8), G. yunnanensis (7), G. longipedalis (5), G. latiscutata (3) |

| Chatia | Chatia maoyi (4), C. hertigi (3), C. alpine (2) |

| Dominant Chigger Species | No. of Hosts | No. and Constituent Ratios (Cr) of Chiggers | Infestation Indexes of Chiggers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hosts Examined | Hosts Infested | No. | Cr, % | PM | MA | MI | |

| L. deliense | 1329 | 313 | 83,008 | 38.13 | 23.55 | 62.46 | 265.20 |

| L. scutellare | 1329 | 197 | 24,839 | 11.41 | 14.82 | 18.69 | 126.09 |

| L. imphalum | 1329 | 175 | 24,313 | 11.17 | 13.17 | 18.29 | 138.93 |

| Total of three dominant mite species | 1329 | 499 | 132,160 | 60.72 | 37.55 | 99.44 | 264.85 |

| 115 chigger species | 1329 | 922 | 217,671 | 100.00 | 69.38 | 163.79 | 236.09 |

| Dominant Host Species | Infestation Indexes of Chiggers | Indexes of Chigger Communities | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM (%) | MA | MI | S | R | H | E | D | |

| R. andamanensis | 95.63 | 370.66 | 387.61 | 83 | 6.94 | 2.29 | 0.52 | 0.23 |

| A. chevrieri | 65.92 | 88.10 | 133.65 | 73 | 6.96 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 0.30 |

| M. caroli | 38.57 | 11.37 | 29.49 | 38 | 4.56 | 2.35 | 0.65 | 0.14 |

| Log Intervals Based on log3M | Individual Ranges of Chiggers in Each Log Interval | Midpoint Values of Each Individual Range | Actual No. of Chigger Species | Theoretical No. of Chigger Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 13.11 |

| 1 | 2–4 | 3 | 12 | 17.91 |

| 2 | 5–13 | 9 | 21 | 21.61 |

| 3 | 14–40 | 27 | 23 | 23.00 |

| 4 | 41–121 | 81 | 11 | 21.61 |

| 5 | 122–364 | 243 | 7 | 17.91 |

| 6 | 365–1093 | 729 | 12 | 13.11 |

| 7 | 1094–3280 | 2187 | 8 | 8.46 |

| 8 | 3281–9841 | 6561 | 13 | 4.82 |

| 9 | 9842–29,524 | 19,683 | 2 | 2.42 |

| 10 | 29,525–88,573 | 59,049 | 1 | 1.08 |

| Months | No. of Hosts | No. and Cr of Chiggers | Infestation Indexes of Chiggers | Indexes of Chigger Community | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hosts Examined | Hosts Infested | No. | Cr, % | PM | MA | MI | S | R | H | E | D | |

| Jan. | 110 | 78 | 11,801 | 5.42 | 70.91 | 107.28 | 151.29 | 50 | 5.23 | 2.13 | 0.55 | 0.18 |

| Feb. | 118 | 89 | 6416 | 2.95 | 75.42 | 54.37 | 72.09 | 32 | 3.54 | 2.24 | 0.65 | 0.13 |

| Mar. | 123 | 91 | 11,699 | 5.37 | 73.98 | 95.11 | 128.56 | 46 | 4.80 | 2.53 | 0.66 | 0.14 |

| Apr. | 104 | 51 | 2799 | 1.29 | 49.04 | 26.91 | 54.88 | 24 | 2.90 | 1.95 | 0.61 | 0.22 |

| May | 104 | 36 | 578 | 0.27 | 34.62 | 5.56 | 16.06 | 26 | 3.93 | 2.37 | 0.73 | 0.13 |

| Jun. | 108 | 40 | 2282 | 1.05 | 37.04 | 21.13 | 57.05 | 21 | 2.59 | 2.04 | 0.67 | 0.17 |

| Jul. | 109 | 63 | 4892 | 2.25 | 57.80 | 44.88 | 77.65 | 21 | 2.35 | 1.41 | 0.46 | 0.40 |

| Aug. | 114 | 93 | 45,750 | 21.02 | 81.58 | 401.32 | 491.94 | 21 | 1.86 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 0.65 |

| Sep. | 110 | 62 | 34,123 | 15.68 | 56.36 | 310.21 | 550.37 | 22 | 2.01 | 1.14 | 0.37 | 0.42 |

| Oct. | 102 | 99 | 39,568 | 18.18 | 97.06 | 387.92 | 399.68 | 24 | 2.17 | 1.19 | 0.37 | 0.46 |

| Nov. | 114 | 110 | 35,870 | 16.48 | 96.49 | 314.65 | 326.09 | 69 | 6.48 | 2.22 | 0.52 | 0.24 |

| Dec. | 113 | 110 | 21,893 | 10.06 | 97.35 | 193.74 | 199.03 | 52 | 5.10 | 2.52 | 0.64 | 0.11 |

| Total | 1329 | 922 | 217,671 | 100.00 | 69.38 | 163.79 | 236.09 | 115 | 9.28 | 2.55 | 0.54 | 0.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lv, Y.; Yin, P.-W.; Guo, X.-G.; Fan, R.; Zhao, C.-F.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Zhang, L. Infestation, Community Structure, and Seasonal Dynamics of Chiggers on Small Mammals at a Focus of Scrub Typhus in Northern Yunnan, Southwest China. Insects 2026, 17, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010031

Lv Y, Yin P-W, Guo X-G, Fan R, Zhao C-F, Zhang Z-W, Zhao Y-F, Zhang L. Infestation, Community Structure, and Seasonal Dynamics of Chiggers on Small Mammals at a Focus of Scrub Typhus in Northern Yunnan, Southwest China. Insects. 2026; 17(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Yan, Peng-Wu Yin, Xian-Guo Guo, Rong Fan, Cheng-Fu Zhao, Zhi-Wei Zhang, Ya-Fei Zhao, and Lei Zhang. 2026. "Infestation, Community Structure, and Seasonal Dynamics of Chiggers on Small Mammals at a Focus of Scrub Typhus in Northern Yunnan, Southwest China" Insects 17, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010031

APA StyleLv, Y., Yin, P.-W., Guo, X.-G., Fan, R., Zhao, C.-F., Zhang, Z.-W., Zhao, Y.-F., & Zhang, L. (2026). Infestation, Community Structure, and Seasonal Dynamics of Chiggers on Small Mammals at a Focus of Scrub Typhus in Northern Yunnan, Southwest China. Insects, 17(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010031