Alternative Prey and Artificial Diet of the Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle Harmonia axyridis: A Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Artificial Diets for Harmonia axyridis

2.1. Alternative Prey

2.1.1. Ephestia kuehniella

2.1.2. Other Lepidoptera Insects

2.1.3. Other Alternative Prey

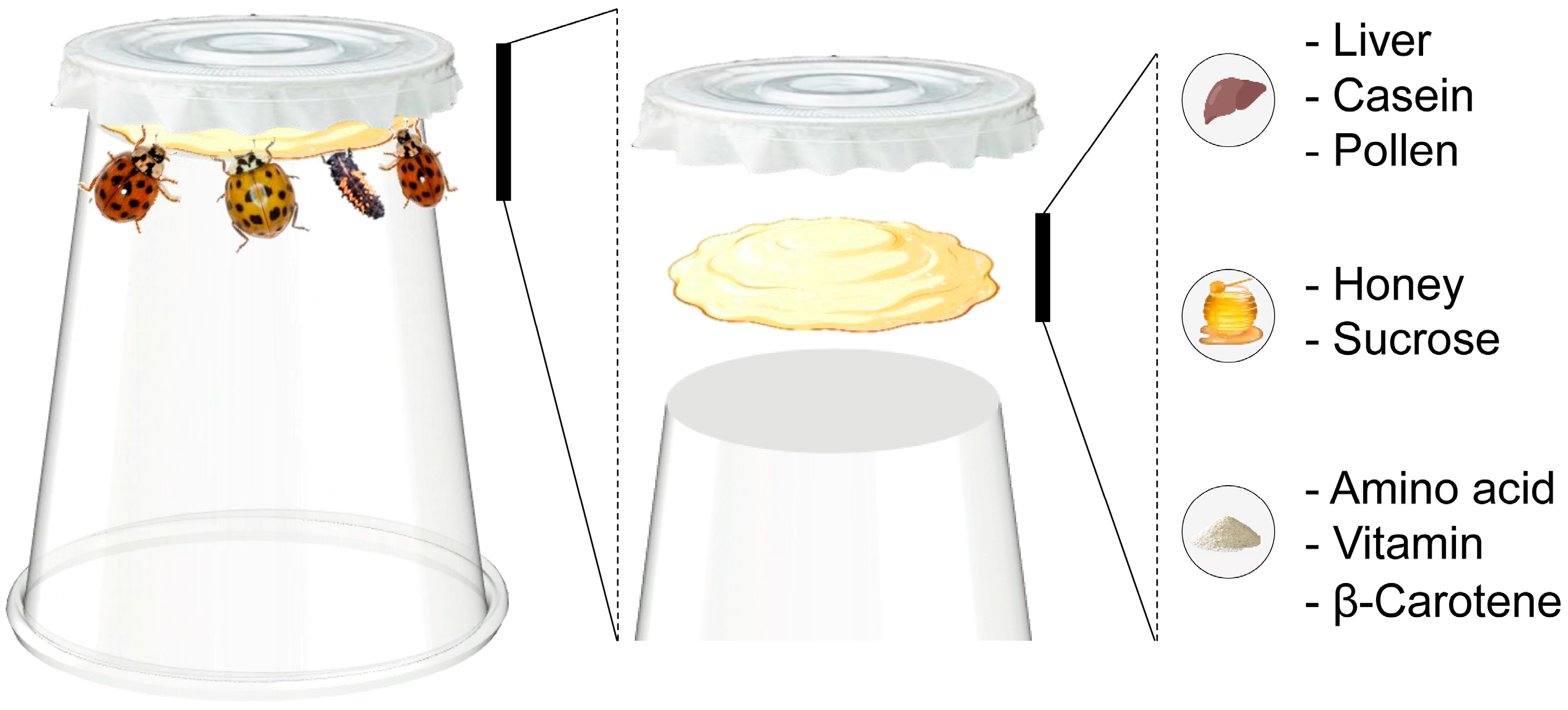

2.2. Artificial Diets

2.2.1. Artificial Diets Based on Alternative Prey

2.2.2. Liver-Based Artificial Diets

3. Nutritional Components and Improvement of Harmonia axyridis Artificial Diets

3.1. Basic Components

3.1.1. Carbohydrates

3.1.2. Proteins and Amino Acids

3.1.3. Lipids and Sterols

3.1.4. Inorganic Salts

3.2. Nutrients for Improving Rearing Quality

3.2.1. Pollen and Nectar

3.2.2. Casein and Milk Powder

3.2.3. Juvenile Hormone

3.2.4. Carotenoids

3.2.5. Nutritional Composition of Aphids and Aphid Honeydew

4. Summary and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Alternative Prey |

| AD | Artificial Diets |

| CK | Control Check |

| VG | Vitellogenin |

| VN | Vitellin |

| JH | Juvenile Hormone |

| ZR512 | Ethyl 3,7,11 trimethyldodeca-2,4-dienoate |

References

- Orlova-Bienkowskaja, M.J.; Ukrainsky, A.S.; Brown, P.M.J. Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in Asia: A re-examination of the native range and invasion to southeastern Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, R.Z.; Zhang, F. Research progress on biology and ecology of Harmonia axyridis pallas (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 2007, 18, 2117–2126. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18062323 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Roy, H.E.; Brown, P.M. Ten years of invasion: Harmonia axyridis (pallas) (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in Britain. Ecol. Entomol. 2015, 40, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, R.L.; Venette, R.C.; Hutchison, W.D. Invasions by Harmonia axyridis (pallas) (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the western hemisphere: Implications for South America. Neotrop. Entomol. 2006, 35, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, R.L. The multicolored Asian lady beetle, Harmonia axyridis: A review of its biology, uses in biological control, and non-target impacts. J. Insect Sci. 2003, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkvens, N.; Landuyt, C.; Deforce, K.; Berkvens, D.; Tirry, L.; De Clercq, P. Alternative foods for the multicoloured Asian lady beetle Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2010, 107, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, É. Évaluation de l’Efficacité de Prédation des Coccinelles, Coccinella septempunctata L. et Harmonia axyridis pallas (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) en Tant qu’Auxiliaires de Lutte Biologique en Vergers de Pommiers. Master’s Thesis, University of Quebec at Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona, H.E.; Zwick, A.; Li, H.S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Pang, H.; Hartley, D.; Jermiin, L.S.; Nedved, O.; Misof, B.; et al. Molecular phylogeny reveals food plasticity in the evolution of true ladybird beetles (coleoptera: Coccinellidae: Coccinellini). BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wu, W.; Peng, Y.; Li, S. Demonstration application research on the control of tobacco aphids using heterogeneous ladybirds. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Jin, J.; Xie, Y.; Ying, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B. Study on the effectiveness of heterocera ladybirds in controlling peach aphids. Bull. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 196–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Yang, R.; Gao, D. Occurrence of aphid in orchard and control of aphid using Harmonia axyridis. Liaoning Agric. Sci. 2005, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Cui, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Lyu, L.; Li, C. The control effects of natural population of Harmonia axyridis to cotton aphids. China Cotton 2014, 41, 8–11. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=HbazLCXbuSU8NTRiXaiBktQr85uZ50mlKmHdK9XLN67BOWPIhGd1XU3ojPCGuSRzKdn7T_VBRP0Wy8eYJFWAMmoQ-FVUCKOdKKNFt_uHKRHAmszt98CRG8bAX5MLEQovEpY5FX5zOQueWxkNt6_pu3BShvZcAdbF6915LAh5jiY5ro59HG7bba76Cz8-ZquX&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Gordon, R. The coleoptera (Coccinellidae) of america north of mexico. J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 1985, 93, 912. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, N.R.; Smith, M.W.; Eikenbary, R.D.; Arnold, D.; Tedders, W.L.; Wood, B.; Landgraf, B.S.; Taylor, G.G.; Barlow, G.E. Assessment of legume and nonlegume ground covers on coleoptera: Coccinellidae density for low-input pecan management. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1998, 13, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, R.; Michaud, J.P.; Olsen, L.; McCoy, C. Lady beetles as potential predators of the root weevil diaprepesabbreviatus (coleoptera: Curculionidae) in florida citrus. Fla. Entomol. 2002, 85, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Miller, S. Coccinellidae (coleoptera) in apple orchards of eastern west virginia and the impact of invasion by Harmonia axyridis. Entomol. News 1998, 109, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Katsoyannos, P.; Kontodimas, D.; Stathas, G.; Tsartsalis, C. Establishment of Harmonia axyridis on citrus and some data on its phenology in Greece. Phytoparasitica 1997, 25, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferran, A.; Niknam, H.; Kabiri, F.; Picart, J.-L.; De Herce, C.; Brun, J.; Iperti, G.; Lapchin, L. The use of Harmonia axyridis larvae (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) against Macrosiphum rosae (hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aphididae) on rose bushes. Eur. J. Entomol. 1996, 93, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Trouve, C.; Ledee, S.; Ferran, A.; Brun, J. Biological control of the damson-hop aphid, Phorodon humuli (hom.: Aphididae), using the ladybeetle Harmonia axyridis (col.: Coccinellidae). BioControl 1997, 42, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Adriaens, T.; Bathon, H.; Cuppen, J.; Goldarazena, A.; Hägg, T.; Kenis, M.; Klausnitzer, B.; Kovář, I.; Loomans, A. Harmonia axyridis in Europe: Spread and distribution of a non-native coccinellid. BioControl 2008, 53, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.; Gagne, I.; Coderre, D. Impact of the arrival of Harmonia axyridis on adults of Coccinella septempunctata and Coleomegilla maculata (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2002, 99, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, W.E.; Clevenger, G.M.; Eigenbrode, S.D. Intraguild predation and successful invasion by introduced ladybird beetles. Oecologia 2004, 140, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colunga-Garcia, M.; Gage, S.H. Arrival, establishment, and habitat use of the multicolored Asian lady beetle (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in a michigan landscape. Environ. Entomol. 1998, 27, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raak-van den Berg, C.L. Harmonia axyridis: How to Explain Its Invasion Success in Europe; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kindlmann, P.; Štípková, Z.; Dixon, A.F. Aphid colony duration does not limit the abundance of Harmonia axyridis in the mediterranean area. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honek, A.; Martinkova, Z.; Roy, H.E.; Dixon, A.F.; Skuhrovec, J.; Pekár, S.; Brabec, M. Differences in the phenology of Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) and native coccinellids in central Europe. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.P.; Trotman, J.; Wheatley, A.; Aebi, A.; Zindel, R.; Brown, P.M. Predation of native coccinellids by the invasive alien Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae): Detection in Britain by pcr-based gut analysis. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2013, 6, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingels, B.; De Clercq, P. Effect of size, extraguild prey and habitat complexity on intraguild interactions: A case study with the invasive ladybird Harmonia axyridis and the hoverfly episyrphus balteatus. BioControl 2011, 56, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Majerus, M.E. Interactions between the parasitoid wasp dinocampus coccinellae and two species of coccinellid from Japan and Britain. BioControl 2008, 53, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.E.; Cottrell, T.E. Forgotten natural enemies: Interactions between coccinellids and insect-parasitic fungi. Eur. J. Entomol. 2008, 105, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, R.; Guo, X.; Wang, S. Progress in pest management by natural enemies in greenhouse vegetables in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2015, 48, 3463–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, F.; Ye, B.; Qi, D.; Li, A. Study on the predatory effects of heterocera ladybirds on white aphids. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1993, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Y.; Ji, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X. Predation of psylla Chinesis yangetli by Harmonia axyridis. J. Plant Prot. 2001, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Yuan, X. Preliminary study on the artificial rearing of heterocera ladybirds and control of the Japanese pine scale insect. In Proceedings of the National Ladybird Symposium, Fuzhou, China, 23 June 1988; pp. 170–171. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, P.; Bonte, M.; Van Speybroeck, K.; Bolckmans, K.; Deforce, K. Development and reproduction of Adalia bipunctata (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on eggs of Ephestia kuehniella (lepidoptera: Phycitidae) and pollen. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005, 61, 1129–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamasaki, K.; Matsui, M. Development and reproduction of an aphidophagous coccinellid, Propylea japonica (thunberg)(coleoptera: Coccinellidae), reared on an alternative diet, Ephestia kuehniella zeller (lepidoptera: Pyralidae) eggs. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2006, 41, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanderl, H.; Ferran, A.; Garcia, V. L ‘élevage de deux coccinelles Harmonia axyridis et semiadalia undecimnotataà l’aide d’oeufs d’Anagasta kuehniella tués aux rayons ultraviolets. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1988, 49, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iperti, G.; Trepanier-Blais, N. Valeur alimentaire des œufs d’Anagasta kuehniella Z.[lepid.: Pyralidae] pour une coccinelle aphidiphage: Adonia 11-notata SCHN.[col. Coccinellidae]. Entomophaga 1972, 17, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukusima, S.; Ohwaki, T. Further Notes on Feeding Biology of Harmonia axyridis Pallas (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae); Gifu University: Gifu, Japan, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Ferran, A.; Gambier, J.; Parent, S.; Legendre, K.; Tourniere, R.; Giuge, L. The effect of rearing the ladybird Harmonia axyridis on Ephestia kuehniella eggs on the response of its larvae to aphid tracks. J. Insect Behav. 1997, 10, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Rodrigues, A.R.; Spíndola, A.F.; de Morais Oliveira, J.E.; Torres, J.B. Dietary effects upon biological performance and lambda-cyhalothrin susceptibility in the multicolored Asian lady beetle, Harmonia axyridis. Phytoparasitica 2013, 41, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricupero, M.; Dai, C.; Siscaro, G.; Russo, A.; Biondi, A.; Zappalà, L. Potential diet regimens for laboratory rearing of the harlequin ladybird. BioControl 2020, 65, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro-Guedes, C.F.; de Almeida, L.M.; do Rocio Chiarello Penteado, S.; Moura, M.O. Effect of different diets on biology, reproductive variables and life and fertility tables of Harmonia axyridis (pallas) (coleoptera, Coccinellidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2016, 60, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkvens, N.; Bonte, J.; Berkvens, D.; Tirry, L.; De Clercq, P. Influence of diet and photoperiod on development and reproduction of European populations of Harmonia axyridis (pallas) (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). BioControl 2008, 53, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerkhove, B.; De Clercq, P. Pollen as an alternative or supplementary food for the mirid predator macrolophus pygmaeus. Biol. Control 2010, 53, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Zanuncio, J.; Serrão, J.; Lima, E.; Figueiredo, M.; Cruz, I. Suitability of different artificial diets for development and survival of stages of the predaceous ladybird beetle eriopis connexa. Phytoparasitica 2009, 37, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettifouri, M.; Ferran, A. Influence of larval rearing diet on the searching behavior of Harmonia axyridis pallas larvae. Entomophaga 1993, 38, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Lin, J. Effectiveness of Harmonia axyridis pallas reared on Ephestia kuehniella zeller eggs as a biological control for aphis craccivora koch. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 56, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Zheng, J.; Miao, L.; Qin, Q. Mass rearing the multicolored Asian lady beetle on beet armyworm larvae. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 49, 1726–1731. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=fAsipVvIRrgMlW65qmicpSnKM0oZJBaEwqpvt9VcDDnnOm9TpeOwDPVrUSvrBAcfJwHDQl4r-sClXBHwTbPbgCtww4Z6cIDegrsxhRXhI7gwLBSG18j7jImYyaUm9dfehjOH9UwwQmScHCruLgQtRO8xP7a11iuSf9rGJxX27o_tLd9bkBSxrY1lL0eVDw6U&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Huang, C.; Hu, F. Studies on the artificial diet and substituted prey of coccinella transversalis. Biol. Disaster Sci. 2019, 42, 238–242. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=DnpHqYycDUPBEpObxzktgclwTBiauUtzWfoEWthk9McoqeU4FVNamCPVJTbk8DfiuzA2RfncIWlQWdeFQ1lfks-Csr37ukD-pHeOPCKWN9sgt40aUQciTvpqNFM1jTd9eYyC0vyGvdcAhbD9hSq0w-ndOhNlhHVE-pQDxFIRcRjKtB6rrMhjPzj5Ta_GCkrGa9OmGiWlneY=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Gao, P.; Zheng, L.; Shi, W.; Tan, X.; Li, F.; Li, Q.; Xu, W. Effects of Mythimna separata on development and fecundity of Harmonia axyridis. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2023, 39, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, L.; Gao, P.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Q.; Li, F.; Xu, W. Optimization of mass rearing conditions for Harmonia axyridis based on Mythimna separata eggs. Plant Prot. 2025, 51, 126–131, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D. Artificial diet feeding and low-temperature preservation trials for heterocera ladybirds. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 1982, 28, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Hu, C.; Gong, H. Effects of feeding drones’ pupae powder on yolk development in ladybird beetle and spotted ladybird eggs. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1992, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wan, F. Effect of three diets on development and fecundity of the ladybeetles Harmonia axyridis and propylaea japonica. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2001, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H. Genetic variation in larval period and pupal mass in an aphidophagous ladybird beetle (Harmonia axyridis) reared in different environments. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2003, 106, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Evaluation of three substitute feeds for the rearing of spotted ladybirds. In Proceedings of the Research on the Prevention and Control of Agricultural Biological Disasters, Beijing, China, 1 October 2005; pp. 977–978. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S. Artificial Breeding and Storage Technology of Harmonia axyridis. Master’s Thesis, Hebei Agriculture University, Baoding, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Qin, Q.; Liu, S.; He, Y. Effect of six diets on development and fecundity of Harmonia axyridis (pallas)(coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Afr. Entomol. 2012, 20, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, A.; Abdel-Baky, N. Life table and biological studies of Harmonia axyridis pallas (col., Coccinellidae) reared on the grain moth eggs of sitotroga cerealella olivier (lep., gelechiidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Ellington, J.; Remmenga, M. An artificial diet for the lady beetle Harmonia axyridis pallas (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Southwest. Entomol. 2001, 26, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Song, H.; Mei, X.; Feng, N.; Chen, F. Preliminary report on the use of domestic silkworm larvae for rearing variegated ladybirds. J. Henan For. Sci. Technol. 2009, 29, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaskar, A.; Evans, E.W. Larval responses of aphidophagous lady beetles (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) to weevil larvae versus aphids as prey. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2001, 94, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W.; Gunther, D.I. The link between food and reproduction in aphidophagous predators: A case study with Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2005, 102, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, T.; Abe, J.; Miura, K. Effect of supplementary food containing artemia salina on the development and survival of flightless Harmonia axyridis in greenhouses. BioControl 2019, 64, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y. Effects of Different Sugar Sources Onproliferations and Pest Control of Harmoniaaxyridis. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Science and Technology, Qinghuangdao, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Specty, O.; Febvay, G.; Grenier, S.; Delobel, B.; Piotte, C.; Pageaux, J.F.; Ferran, A.; Guillaud, J. Nutritional plasticity of the predatory ladybeetle Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae): Comparison between natural and substitution prey. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2003, 52, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, C.; Liang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Han, S.; He, Y. Effects of three diets on growth and reproduction of Harmonia axyridis (pallas). For. Ecol. Sci. 2017, 32, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, W. An artificial diet for rearing coccinellid beetles. Can. Entomol. 1958, 90, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insect Physiology Laboratory, Beijing Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Preliminary report on artificial rearing and breeding trials of seven-spotted ladybirds and variegated ladybirds. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 1977, 58–60. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=rq9xis5c9i8wLNDQ_un0DfmlNihFXmQLs8sC98M7P0bYrUl8UP4ou3oroQ6V9_Yzhwgazw9HzeoJ79pnuL9Ze2yIw_BKe76mUi4SojltLZeRIjgjFK67AmzZHAO1wFHJNALqYZipL2PUxt9mmncQasrZtMlWyhJsoTabYeTX3sdf9lPqXMHh1V65nPTU7tEe&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Sun, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, Z.; He, J.; Ye, W. Preliminary study on artificial diet for heterocera ladybirds and control of aphids in greenhouse-grown strawberries. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Agric. Sci. 1996, 10, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Berkvens, N.; Bonte, J.; Berkvens, D.; Deforce, K.; Tirry, L.; De Clercq, P. Pollen as an alternative food for Harmonia axyridis. BioControl 2008, 53, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatt, S.; Osawa, N. The role of perilla frutescens flowers on fitness traits of the ladybird beetle Harmonia axyridis. BioControl 2019, 64, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G.; Li, F.; Xu, W. Effects of sugar sources on the rearing system of “Mythimna separate-Harmonia axyridis”. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2024, 40, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, L. Preliminary report on artificial propagation techniques for heterocera ladybirds. Liaoning For. Sci. Technol. 1979, 6, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, Y. Preliminary study on artificial substitute feed for variegated ladybirds. Shaanxi J. Agric. Sci. 1982, 14, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.R. Study on Artifical Diets for Rearing Larvae of Harmonia axyridis (Pallas). Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, F. Advances of artificial diet for Harminia axyridis. J. Mt. Agric. Biol. 2003, 22, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, S. The effect of different dietary sugars on the development and fecundity of Harmonia axyridis. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 574851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Mao, J.; Zeng, F. Effects of an artificial diet with non-insect ingredient on biological characteristics of Harmonia axyridis(pallas). Chin. J. Biol. Control 2015, 31, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Zhang, S.; Luo, J.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Lv, L.-M.; Cui, J.-J. Artificial diet development and its effect on the reproductive performances of Propylea japonica and Harmonia axyridis. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2016, 19, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Lv, J.; Huang, Z.; Pu, Z.; Liu, S. Artificial diets can manipulate the reproductive development status of predatory ladybird beetles and hold promise for their shelf-life management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, L.; Febvay, G.; Dindo, M.L.; Rey, M.; Pageaux, J.; Baronio, P.; Grenier, S. Biological and biochemical characteristics for quality control of Harmonia axyridis (pallas) (coleoptera, Coccinellidae) reared on a liver-based diet. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2008, 68, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Peng, S. The effect of artificial diet on the growth and development of variegated ladybird larvae. Mod. Agric. 2008, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, L.; Febvay, G.; Dindo, M.L.; Rey, M.; Pageaux, J.F.; Grenier, S. Biochemical content in fatty acids and biological parameters of Harmonia axyridis reared on artificial diet. Bull. Insectol. 2013, 66, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.X.; Chen, M.J.; Hao, Y.N.; Wang, S.S.; Zhang, C.L. Canola bee pollen is an effective artificial diet additive for improving larval development of predatory coccinellids: A lesson from Harmonia axyridis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 2920–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, J.; Chi, B.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.J. Effect of different diets on the growth and development of Harmonia axyridis (pallas). J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 144, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervet, V.A.D.; Laird, R.A.; Floate, K.D. A review of the mcmorran diet for rearing lepidoptera species with addition of a further 39 species. J. Insect Sci. 2016, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Moore, R.F. Handbook of Insect Rearing; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, J.R. The evolution of artificial diets and their interactions in science and technology. In Insect Bioecology and Nutrition for Integrated Pest Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 51–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, C.; Chen, D.; Deng, H.; Wu, S. Analyzing nutritional components of Myzus persicae nymphs. Tob. Sci. Technol. 2024, 57, 75–83. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.16135/j.issn1002-0861.2024.0335 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Pringle, E.G.; Novo, A.; Ableson, I.; Barbehenn, R.V.; Vannette, R.L. Plant-derived differences in the composition of aphid honeydew and their effects on colonies of aphid-tending ants. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 4065–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, P.D.; Heuskin, S.; Sabri, A.; Verheggen, F.J.; Farmakidis, J.; Lognay, G.; Thonart, P.; Wathelet, J.P.; Brostaux, Y.; Haubruge, E. Honeydew volatile emission acts as a kairomonal message for the Asian lady beetle Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insect Sci. 2012, 19, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Huang, Q. Tissue culture and plantlet regeneration from leaves of nicotiana tabacum. Subtrop. Plant Sci. 2003, 32, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F. Research of insect artificial diet. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2018, 34, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M. Cold tolerance and myo-inositol accumulation in overwintering adults of a lady beetle, Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2002, 99, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshikawa, K. Accumulation of inositol by hibernating adults of coccinellid and chrysomelid beetles. Low Temp. Sci. B Biol. Sci. 1982, 39, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan, T.L.; Koch, R.L.; Hutchison, W.D. Impact of fruit feeding on overwintering survival of the multicolored Asian lady beetle, and the ability of this insect and paper wasps to injure wine grape berries. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2008, 128, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, J.G. Nutritional aspects of non-prey foods in the life histories of predaceous Coccinellidae. Biol. Control 2009, 51, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niijima, K.; Nishimura, R.; Matsuka, M. Nutritional studies of an aphidophagous coccinellid, Harmonia axyridis [iii]. Rearing of larvae using a chemically defined diet and fractions of drone honeybee powder. Kenkyu Hokoku Bull. 1977, 12, 325–329. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19780207998 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Jing, Z.; Shu, L.; Zhenzhen, C.; Su, W.; Yongyu, X. Effects of cold stress on survival and activities of several enzymes in multicolored Asian lady beetle Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera:Coccinellidae) adults. Acta Phytophylacica Sin. 2014, 41, 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Xiao, Z.; Zeng, B.; Ni, X.; Tang, B. Expression and function of trehalase genes tre2-like and tre2 during adult eclosion in Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2019, 62, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; He, J.; Chao, L.; Shi, Z.; Wang, S.; Yu, W.; Huang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. Regulatory role of trehalose metabolism in cold stress of Harmonia axyridis laboratory and overwinter populations. Agronomy 2023, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.S.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.G.; Tang, B.; Liu, F. Involvement of glucose transporter 4 in ovarian development and reproductive maturation of Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insect Sci. 2022, 29, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnícek, J. Insect diets: Science and technology. Eur. J. Entomol. 2004, 101, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wan, F. General Entomology; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coppin, F.; Michon, J.; Garnier, C.; Frelon, S. Fluorescence quenching determination of uranium (vi) binding properties by two functional proteins: Acetylcholinesterase (ache) and vitellogenin (vtg). J. Fluoresc. 2015, 25, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Yang, W.J.; Jiang, X.Z.; Niu, J.Z.; Shen, G.M.; Ran, C.; Wang, J.J. The essential role of vitellogenin receptor in ovary development and vitellogenin uptake in bactrocera dorsalis (hendel). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18368–18383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Takeda, M. Molecular characteristics of insect vitellogenins. J. Insect Physiol. 2008, 54, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Q.; Ji, X.; Wang, W.; Yuan, H.; Rui, C.; Cui, L. Sulfoxaflor adversely influences the biological characteristics of Coccinella septempunctata by suppressing vitellogenin expression and predation activity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 447, 130787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, F.; Mao, J.; Liang, H.; Liu, F. Molecular cloning of the vitellogenin gene and the effects of vitellogenin protein expression on the physiology of Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, F.; Mao, J.; Zhang, G. Search for nutritional fitness traits in a biological pest control agent Harmonia axyridis using comparative transcriptomics. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidugli-Lazzarini, K.R.; do Nascimento, A.M.; Tanaka, E.D.; Piulachs, M.D.; Hartfelder, K.; Bitondi, M.G.; Simoes, Z.L. Expression analysis of putative vitellogenin and lipophorin receptors in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) queens and workers. J. Insect Physiol. 2008, 54, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Pakkianathan, B.C.; Kumar, M.; Prasad, T.; Kannan, M.; Konig, S.; Krishnan, M. Vitellogenin from the silkworm, bombyx mori: An effective anti-bacterial agent. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, H.; Liang, G.; Guo, Y.; Wu, K. Tradeoff between reproduction and resistance evolution to bt-toxin in helicoverpa armigera: Regulated by vitellogenin gene expression. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2014, 104, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.C. Insect Diets: Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hixson, A. Developmental Steroids and Vitamins: Identified and Quantified in Predatory Lady Beetles; University of Tennessee at Chattanooga: Chattanooga, TN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ugine, T.A.; Krasnoff, S.B.; Behmer, S.T. Omnivory in predatory lady beetles is widespread and driven by an appetite for sterols. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Moon, Y.S.; Pack, I.S.; Kim, C.G. Salinity affects metabolomic profiles of different trophic levels in a food chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuka, M.; Takahashi, S. Nutritional studies of an aphidophagous coccinellid Harmonia axyridis: II. Significance of minerals for larval growth. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1977, 12, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B. Stduies on Mass Rearing and Field Releasetechnology of Harmonia axyridis. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agriculture University, Wuhan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Effects of pollen and nectar sources on biological characteristics of Harmonia axyridis. J. Hebei Agric. Sci. 2024, 28, 74–77, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, J.G. Pollen nutrition and defense. BioControl 2009, 53, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, J.G.; Razzak, A.A.; Wiedenmann, R.N. Population responses and food consumption by predators Coleomegilla maculata and Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) during anthesis in an illinois cornfield. Environ. Entomol. 2004, 33, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Ouyang, F.; Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Ge, F. Cnidium monnieri (L.) cusson flower as a supplementary food promoting the development and reproduction of ladybeetles Harmonia axyridis (pallas)(coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Plants 2023, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, F.; Soares, M.A.; Basiri, S.E.; Amiens-Desneux, E.; Campos, M.R.; Lavoir, A.-V.; Desneux, N. Effects of four non-crop plants on life history traits of the lady beetle Harmonia axyridis. Entomol. Gen 2020, 40, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, C.R.; Brown, M.W.; Wackers, F.L. Comparison of peach cultivars for provision of extrafloral nectar resources to Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Environ. Entomol. 2016, 45, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Romeis, J.; Collatz, J. Utilization of plant-derived food sources from annual flower strips by the invasive harlequin ladybird Harmonia axyridis. Biol. Control 2018, 122, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, M.; Qin, Y.; Zhong, M. Effects of pollen-added artificial diets on the development of Harmonia axyridis larvae. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2023, 39, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jin, S.; Sun, Y.; Guo, J. Effects of supplementary feeding of canola pollen on the larval development and adult reproduction of Harmonia axyridis. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2024, 41, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, J.G. Relationships of Natural Enemies and Non-Prey Foods; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, M.; Saqib, S.M. Rearing of predatory seven spotted ladybird beetle Coccinella septempunctata L. (coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on natural and artificial diets under laboratory conditions. Pak. J. Zool. 2010, 42, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhi, J.; Li, F.; Jin, J.X.; Zhou, Y. An artificial diet for continuous maintenance of Coccinella septempunctata adults (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jin, S.; Sun, Y.; Guo, J. Effects of modifying artificial diet components on the growth and development of seven-spotted ladybird larvae acta entomologica sinica. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1989, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ran, H.; Jin, J.; Li, F. An orthogonal design to improve an artificial diet for adult of Coccinella septempunctata L. (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2023, 60, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, R.; Liu, H.; Feng, C.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Q.; Guo, S.; Li, B.; Guan, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Effect of artificial feed on the biological characteristics of adult Coccinella septempunctata. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2020, 36, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Saha, T.T.; Zou, Z.; Raikhel, A.S. Regulatory pathways controlling female insect reproduction. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Q.-H.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Gong, H. Regulation of vitellogenin synthesis by juvenile hormone analogue in Coccinella septempunctata. Insect Biochem. 1987, 17, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, B.; Tian, Z.; De Loof, A.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, X.P.; Liu, W. Key role of juvenile hormone in controlling reproductive diapause in females of the Asian lady beetle Harmonia axyridis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J.J.; Cipollini, D.F.; Stireman, J.O., III. The role of carotenoids and their derivatives in mediating interactions between insects and their environment. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2013, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, E.; Moran, N.A. Diversification of genes for carotenoid biosynthesis in aphids following an ancient transfer from a fungus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-X.; Hao, Y.-N.; Liu, T.-X. A β-carotene-amended artificial diet increases larval survival and be applicable in mass rearing of Harmonia axyridis. Biol. Control 2018, 123, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, C.; Cai, P.; Li, Y.; He, H.; Pu, D. Effects of different carotene concentrations and feed preparation methods on larvae of Coccinella septempunctata. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2021, 37, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Guo, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Wu, X.; Pu, D. Effects of β-carotene and feed froms on biology of adult Coccinella septempunctata. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, K. Composition of the honeydew of the aphid Brevicoryne brassicae (L.) feeding on swedes (Brassica napobrassica DC.). J. Insect Physiol. 1959, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring, J.; Wiedemann, R.; Völkl, W.; Hoffmann, K.H. Oligosaccharide synthesis regulates gut osmolality in the ant-attended aphid Metopeurum fuscoviride but not in the unattended aphid Macrosiphoniella tanacetaria. J. Appl. Entomol. 2007, 131, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogervorst, P.A.; Wäckers, F.L.; Romeis, J. Effects of honeydew sugar composition on the longevity of Aphidius ervi. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2007, 122, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring, J.; Wiedemann, R.; Fischer, M.K.; Hoffmann, K.H.; Völkl, W. Honeydew amino acids in relation to sugars and their role in the establishment of ant-attendance hierarchy in eight species of aphids feeding on tansy (Tanacetum vulgare). Physiol. Entomol. 2004, 29, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirande, L.; Desneux, N.; Haramboure, M.; Schneider, M.I. Intraguild predation between an exotic and a native coccinellid in argentina: The role of prey density. J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, R.; Hutchison, W.; Venette, R.; Heimpel, G. Susceptibility of immature monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Danainae), to predation by Harmonia axyridis (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Biol. Control 2003, 28, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Lövei, G.L.; Wu, X.; Wan, F.H. Presence of native prey does not divert predation on exotic pests by Harmonia axyridis in its indigenous range. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.F.G. Insect Predator-Prey Dynamics: Ladybird Beetles and Biological Control; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, P.; Lebrun, B.; Braekman, J.-C.; Daloze, D.; Pasteels, J.M. Biosynthetic studies on adaline and adalinine, two alkaloids from ladybird beetles (coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3403–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, D.W. Harmonia axyridis ladybug invasion and allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008, 29, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, P.G.; De Clercq, P.; Heimpel, G.E.; Kenis, M. Attributes of biological control agents against arthropods: What are we looking for? In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Biological Control of Arthropods (ISBCA 3), Christchurch, New Zealand, 8–13 February 2008; pp. 385–392. [Google Scholar]

| Alternative Prey (AP) | Control Check (CK) | Effects of Ladybirds’ Feeding (AP vs. CK) | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Species | Life Stage | Treatment | Larvae | Adult | ||

| Lepidoptera | Ephestia kuehniella | Eggs | UV Treatment 25 min + freezing 15 days | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Developmental duration: 14.1 d vs. 14.8 d Survival rate: 85% vs. 80% | Adult body weight: 24.4 mg vs. 29.6 mg | [35] |

| Eggs | UV-treated and frozen for storage | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Developmental duration: 14.1 d vs.14.5 d Survival rate: 96.7% vs. 76.2% * | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 393 eggs vs. 154 eggs * Adult body weight: 36.1 mg vs. 29.4 mg * | [36] | ||

| Eggs | Laboratory rearing | Aphis gossypii | Developmental duration: 14.9 d vs. 14.3 d Survival rate: 91.7% vs.91.7% | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 379.6 eggs vs. 302.1 eggs | [37] | ||

| Eggs | Frozen | Cinara atlantica | Developmental duration: 22.8 d vs. 22.4 d | Egg hatchability: 7.2 d vs. 6.9 d Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 555.5 eggs vs. 747.5 eggs * Adult body weight: 24.7 mg vs. 25.8 mg * | [38] | ||

| Eggs | Frozen | Brevicoryne brassicae | Developmental duration: 22.8 d vs. 22.5 d | Egg hatchability: 7.2 d vs. 6.1 d - Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 555.5 eggs vs. 641.0 eggs * Adult body weight: 24.7 mg vs. 25.5 mg * | [38] | ||

| Eggs | Frozen | Aphis gossypii | Developmental duration: 14.07 d vs. 15 d * Survival rate: 82.1% vs. 87.7% | Egg hatchability: 21.3 d vs. 13.9 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 387.8 eggs vs. 236.3 eggs * Adult body weight: 33.6 mg vs. 27.8 mg * | [39] | ||

| Corcyra cephalonica | Eggs | Frozen eggs | Myzus persicae | Survival rate: 0% vs. 87.7% ** | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 0 vs. 236.3 eggs ** | [40] | |

| Sitotroga cerealella | Eggs | Fresh | Sitotroga cerealella frozen eggs | Developmental duration: 11.2 d vs. 13.4 d Survival rate: 84% vs. 80% * | Egg hatchability: 8.1 d vs. 9.5 d Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 715.3 eggs vs. 606.6 eggs * Adult body weight: 26.8 mg vs. 23.1 mg * | [41] | |

| Eggs | Stored at 4 °C | Chaitophorus populeti | Developmental duration: 11.3 d vs. 9.3 d * Survival rate: 72.1% vs. 90% ** | Egg hatchability: 31.1 d vs. 7.4 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 135.6 eggs vs. 732.7 eggs * | [42] | ||

| Eggs | Aphis gossypii | Developmental duration: 19.7 d vs. 14.3 d * Survival rate: 47.9% vs. 91.7% * | Egg hatchability: 17.3 d vs. 7.3 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 51.6 eggs vs. 302.1 eggs ** Adult body weight: 19.9 mg vs. 23.0 mg * | [37] | |||

| Eggs | Frozen eggs | Lipaphis erysimi | Developmental duration: 39.5 d vs. 25.3 d * Survival rate: 56.7% vs. 77.7% * | Egg hatchability: 18.3 d vs. 11.0 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 391.9 eggs vs. 929.3 eggs | [43] | ||

| Pectinophora gassypiella | Eggs | Fresh | Sitotroga cerealella | Developmental duration: 19.0 d vs. 18.0 d Survival rate: 94.0% vs. 91.0% | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: lower * Adult body weight: 27.0 mg vs. 23.0 mg * | [44] | |

| Bombyx mori | Larvae | Live | Aphids | Developmental duration: 9.2 d vs. 9.5 d Survival rate: 98.3% vs. 95.0% | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 85.5 eggs vs. 297.6 eggs * Adult body weight: 29.6 mg vs. 29.3 mg | [45] | |

| Mythimna separata | Eggs | Frozen eggs | Aphis craccivora | Developmental duration: 9.9 d vs. 9.7 d | Egg hatchability: 12.3 d vs. 8.9 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 987.1 eggs vs. 1175.5 eggs * | [46] | |

| Hymenoptera | Trichogrammatidae | Pupa | Refrigerated | Myzus persicae | Developmental duration: 12.3 d vs. 10.3 d ** Survival rate: 81.2% vs. 84.6% | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 0 vs. 404.1 eggs ** Adult body weight: 20.2 mg vs. 22.4 mg ** | [40] |

| Coleoptera | Hypera postica | Larvae | Live | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 0 vs. 508.5 eggs ** | [47] | |

| Anostraca | Artemia salina | Cyst | With shell | Aphis gossypii | Developmental duration: 19.0 d vs. 15.0 d * Pupal weight: 27.0 mg vs. 40.0 mg * Emergence rate: 72.5% vs. 78.8% - | Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 151.8 eggs vs. Not measured Egg hatchability: 25.1% vs. Not measured | [48] |

| Artificial Diets (AD) | Control Check (CK) | Effects of Ladybirds’ Feeding (AD vs. CK) | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Components | Other Components | Larvae | Adult | ||

| Pig liver | Sucrose, honey, silkworm pupal powder, water | Aphids | Developmental duration: 21.3 d vs. 21.1 d Pupal weight: 28.9 mg vs. 21.7 mg | Pre-oviposition period: 26.7 d vs. 13 d Lifespan: 52.9 d vs. 55.1 d Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 152.7 eggs vs. 200.9 eggs | [72] |

| Pig liver | Isio 4 oil, olive oil, sucrose, glycerol, amino acid solution (including tyrosine, histidine, arginine, ethanolamine), yeast extract, Vanderzant vitamin mix | Ephestia kuehniella eggs | Egg hatchability: 27.6% vs. 91.5% * Developmental duration: 25.5 d vs.15.3 d * | Pre-oviposition period: 13.5 d vs. 6.0 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 47 eggs vs. 483 eggs * Adult body weight: 21.0 mg vs. 38.5 mg * | [73] |

| Pig liver | Honey | Chaitophorus populeti | Developmental duration: 14.83 d vs. 14.5 d - Pupal duration: 3.6 d vs. 4.0 d * | [74] | |

| Pig liver | Honey, sucrose, water, preservatives (potassium sorbate, penicillin, etc.) | Chaitophorus populeti | Developmental duration: 14.3 d vs. 9.3 d * Survival rate: 11.6% vs. 90.0% * | Pre-oviposition period: 29.0 d vd. 7.4 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 68.5 eggs vs. 732.7 eggs * Adult body weight: 25.5 mg vs. 27.0 mg * | [42] |

| Pig liver | Flaxseed oil, olive oil, sucrose, glycerol, amino acid solution, yeast extract, vitamin mix | Ephestia kuehniella eggs | Developmental duration: 20.5 d vs. 12.5 d * Survival rate: 31.7% vs. 86.0% * | Pre-oviposition period: 13.6 d vs. 7.3 d * Lifespan: 93 d vs. 75 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 37 eggs vs. 324 eggs * Adult body weight: 20.1 mg vs. 31.8 mg * | [75] |

| Pig liver | Fly larval powder, yeast extract, sucrose, honey | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Survival rate: 91% vs. 100% - Developmental duration: 17.0 d vs. 13.7 d * | Adult body weight: 31.0 mg vs. 26.0 mg * | [76] |

| Pig liver | Honey, sucrose, olive oil, insect-specific multivitamins | Lipaphis erysimi | Developmental duration: 8.2 d vs. 14.1 d * Survival rate: 45.3% vs.77.7% * | Pre-oviposition period: 17.2 d vs. 11.7 d * Lifespan: 78.6 d vs. 95.5 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 262.3 eggs vs. 929.3 eggs * | [43] |

| Pig liver | Honey, vitamin C, sugars, royal jelly, glucose, trehalose | Aphids | Developmental duration: 24.5 d vs. 21.5 d * | Pre-oviposition period: 11.8 d vs. 7.9 d - Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 527.7 eggs vs. 830 eggs * | [77] |

| Pig liver powder | Yeast, sucrose, honey, vegetable oil, potassium sorbate solution, rapeseed pollen, distilled water | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Survival rate: 88.3% vs. 96.7% - Development time: 25.6 d vs. 14.5 d ** | Adult body weight: 20.4 mg vs. 32.1 mg ** Lipid content: significantly higher than in the aphid-fed group | [78] |

| Pig liver | Egg, pork, brown sugar, vitamins and preservatives (based on [79] improvement) | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Survival rate: 82.2% vs. 71.1% * Developmental duration: 16.2 d vs. 12.5 d * | Pre-oviposition period: 19.8 d vs. 8.9 d * Lifespan: 103.6 d vs. 85.7 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 23.5 eggs vs. 437.3 eggs * | [80] |

| Pig liver | Egg white, egg, wheat germ, honey, brewer’s yeast, refined sugar, beef, milk, etc. (AD), multivitamins, sodium benzoate, parabens | Aphis gossypii | Survival rate: 65.6% vs. 87.7% * Developmental duration: 21.7 d vs. 15.0 d * | Adult body weight: 18.0 mg vs. 27.8 mg * Pre-oviposition period: 40.7 d vs. 13.9 d * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 60.7 eggs vs. 236.3 eggs * | [39] |

| Pig liver | Whole egg liquid, pork, yeast extract, royal jelly, sucrose, amino acid mixture, Wess salts, olive oil, soybean oil, vitamin B complex, vitamin C, cephalosporin, methylparaben, potassium sorbate, fava bean leaves, etc. | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Survival rate: 66.4% vs. 81.7% Developmental duration: 18.7 d vs. 12.6 d * | Adult body weight: 20.6 mg vs. 23.6 mg * Fecundity/Total eggs laid: 0 vs. 1158.3 eggs * | [81] |

| Chicken liver | Sucrose, honey, brewer’s yeast, casein hydrolysate, soybean oil, salt mixture [82], Vanderzant vitamin supplement, bulb starch | Sitotroga cerealella eggs | Developmental duration: 22.5 d vs. 18.0 d * Survival rate: 94.0% vs. 93.0% - | Adult body weight: 27.5 mg vs. 27.0 mg - | [44] |

| Beef liver | Shrimp, beef, egg yolk, honey, sucrose, yeast extract, vitamin powder, olive oil, etc. | Acyrthosiphon pisum | Developmental duration: 13.9 d vs. 9.0 d * | Adult body weight: 17.2 mg vs. 24.0 mg * | [83] |

| Components | Research Object | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aulacorthum solani | Macrosiphum euphorbiae | Sitobion avenae | Rhopalosiphum padi | Myzus persicae | Metopeurum fuscoviride | Brachycaudus cardui | Trama troglodytes | A. fabae | Macrosiphoniella tanacetaria | ||

| Solanum tuberosum | Triticum aestivum | Solanum tuberosum | Triticum aestivum | Tanacetum vulgare | |||||||

| [147] | [148] | ||||||||||

| Fructose | 20 | 15.70 | 28.3 | 68.4 | 41.2 | 43.2 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 28 | 8.3 | 10.6 |

| Glucose | 9.20 | 2 | 5.9 | 14.8 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 8.4 | 2.5 | 11.9 | 25.9 |

| Sucrose | 44.50 | 60 | 45.3 | 5.9 | 30.9 | 26 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

| Trehalose | 4.80 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 14.2 | 20.1 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 44.6 |

| Raffinose | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.3 | 8.5 | 0.1 |

| Maltose | 1.50 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 6 | 0.8 |

| Isomaltulose | 18.30 | 18 | 16.7 | 5.6 | 12.1 | 15.6 | 62.7 | 52.4 | 54.9 | 54.1 | 16.6 |

| Melibiose | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | / | / | / | / | / |

| Mannitol | 1.60 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | / | / | / | / | / |

| Sorbitol | 0.10 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | / | / | / | / | / |

| Components | Research Object | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphis nerii | Metopeurum fuscoviride | Brachycaudus cardui | Trama troglodytes | Aphis fabae | Macrosiphoniella tanacetaria | ||

| Asclepias incarnata | Asclepias curassavica | Tanacetum vulgare | |||||

| [92] | [148] | ||||||

| Glu | 12.0 | 29.0 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 8.9 | 14.3 | 4.7 |

| Ser | 26.0 | 47.0 | 13.8 | 3.7 | 11.1 | 4.1 | 12.5 |

| Gln | / | / | 16.1 | 43.7 | 29 | 15.2 | 6.2 |

| Asn | / | / | 17.3 | 11.9 | 15.2 | 9.9 | 39.6 |

| Asp | 5.0 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 7.3 |

| Pro | 23.0 | 19.0 | 4 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 5.2 |

| Val a | 3.0 | 2.0 | / | / | / | / | / |

| Val a/Trp a | / | / | 3.2 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 10.3 | 1.1 |

| Ile a | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| Leu | 11.0 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.3 |

| Phe a | 9.0 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 0 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| Arg a | / | / | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Gly | / | / | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Thr a | / | / | 9.7 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 8.9 |

| Tyr | / | / | 12.4 | 6.3 | 1.4 | 5.5 | 4.8 |

| Ala | / | / | 2.7 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| Met a | / | / | 0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 2.3 |

| Cys | / | / | 0 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.9 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, Q.; Gao, R.; Zheng, L.; Xue, K.; Ren, Z. Alternative Prey and Artificial Diet of the Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle Harmonia axyridis: A Review. Insects 2026, 17, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010016

Zeng Q, Gao R, Zheng L, Xue K, Ren Z. Alternative Prey and Artificial Diet of the Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle Harmonia axyridis: A Review. Insects. 2026; 17(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Qingqiu, Rongrong Gao, Lamei Zheng, Kun Xue, and Zhentao Ren. 2026. "Alternative Prey and Artificial Diet of the Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle Harmonia axyridis: A Review" Insects 17, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010016

APA StyleZeng, Q., Gao, R., Zheng, L., Xue, K., & Ren, Z. (2026). Alternative Prey and Artificial Diet of the Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle Harmonia axyridis: A Review. Insects, 17(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010016