Global Distribution of Three Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae): Present and Future Climate Change Scenarios

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

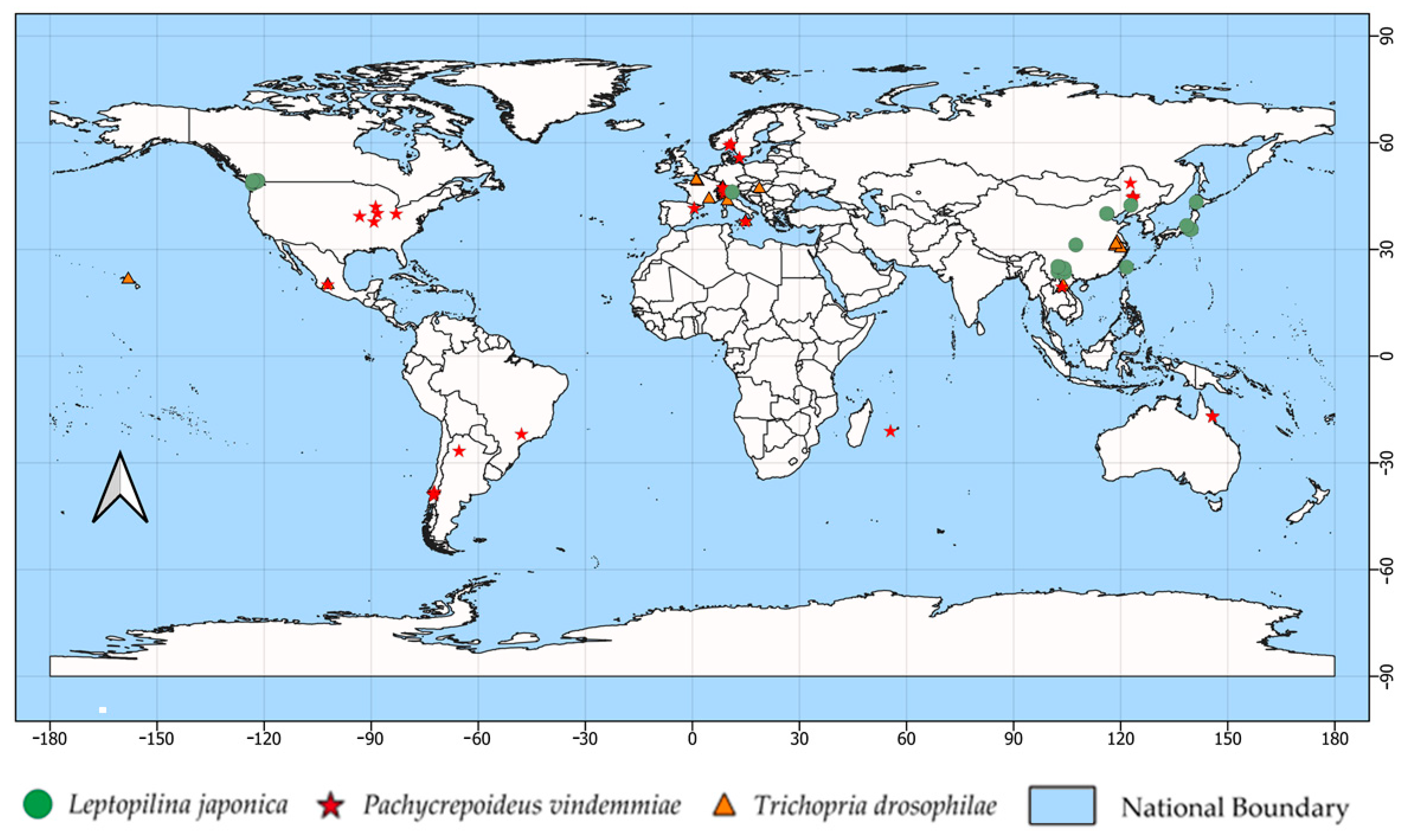

2.1. Occurrence Data of Spotted Wing Drosophila Parasitoids

2.2. Climate Layers

2.3. Current and Future Potential Distribution Modeling

2.4. Model Evaluation

2.5. Estimation of the Potential Overlap Between the Parasitoids and SWD

3. Results

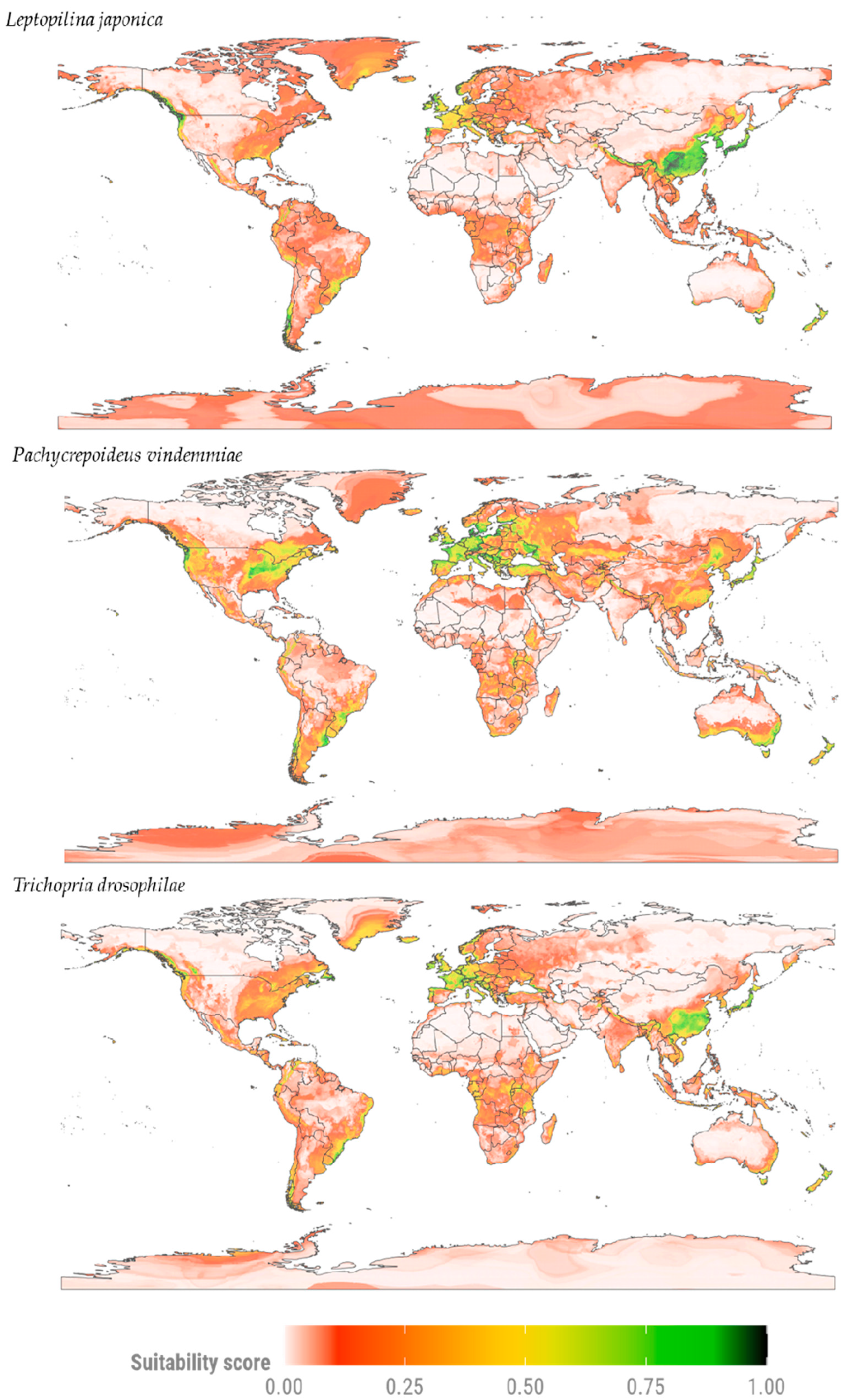

3.1. Current Potential Distribution of D. suzukii Parasitoids

3.2. Potential Distribution of SWD Parasitoids Under Two Climate Change Scenarios

3.2.1. Moderate Mitigation Scenario (SSP2-4.5)

3.2.2. Pessimistic Mitigation Scenario (SSP5-8.5)

3.3. Overlap of the Current Potential Distribution of SWD and Its Parasitoids

3.4. Overlap of the Future Expansion of SWD and Its Promising Parasitoids Under Climate Change Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fuglie, K.O.; Morgan, S.; Jelliffe, J. World Agricultural Production, Resource Use, and Productivity, 1961–2020; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The Global Burden of Pathogens and Pests on Major Food Crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vreysen, M.J.B.; Robinson, A.S.; Hendrichs, J.; Kenmore, P. Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management (AW-IPM): Principles, Practice and Prospects. In Area-Wide Control of Insect Pests; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Girod, P.; Lierhmann, O.; Urvois, T.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Kenis, M.; Haye, T. Host Specificity of Asian Parasitoids for Potential Classical Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Bregaglio, S.; Willocquet, L.; Gustafson, D.; Mason D’Croz, D.; Sparks, A.; Castilla, N.; Djurle, A.; Allinne, C.; Sharma, M.; et al. Crop Health and Its Global Impacts on the Components of Food Security. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, S.K. Integrated Insect Pest Management of Economically Important Crops. In Biopesticides in Organic Farming; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Asplen, M.K.; Anfora, G.; Biondi, A.; Choi, D.-S.; Chu, D.; Daane, K.M.; Gibert, P.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Hutchison, W.D.; et al. Invasion Biology of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii): A Global Perspective and Future Priorities. J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughdad, A.; Haddi, K.; El Bouazzati, A.; Nassiri, A.; Tahiri, A.; El Anbri, C.; Eddaya, T.; Zaid, A.; Biondi, A. First Record of the Invasive Spotted Wing Drosophila Infesting Berry Crops in Africa. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Vega, G.J.; Corley, J.C. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Distribution Modelling Improves Our Understanding of Pest Range Limits. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2019, 65, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.P.; Ponti, L.; Dalton, D.T. Analysis of the Invasiveness of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) in North America, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 3647–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota-Stabelli, O.; Ometto, L.; Tait, G.; Ghirotto, S.; Kaur, R.; Drago, F.; González, J.; Walton, V.M.; Anfora, G.; Rossi-Stacconi, M.V. Distinct Genotypes and Phenotypes in European and American Strains of Drosophila suzukii: Implications for Biology and Management of an Invasive Organism. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, M. A Historic Account of the Invasion of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in the Continental United States, with Remarks on Their Identification. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, A.; Ioriatti, C.; Anfora, G. A Review of the Invasion of Drosophila suzukii in Europe and a Draft Research Agenda for Integrated Pest Management. Bull. Insectol. 2012, 65, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dreves, A.J.; Walton, V.; Fisher, G.A. A New Pest Attacking Healthy Ripening Fruit in Oregon: Spotted Wing Drosophila. Available online: https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/em8991 (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Walton, V.M.; Burrack, H.J.; Dalton, D.T.; Isaacs, R.; Wiman, N.; Ioriatti, C. Past, Present and Future of Drosophila suzukii: Distribution, Impact and Management in United States Berry Fruits. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1117, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.B.; Bolda, M.P.; Goodhue, R.E.; Dreves, A.J.; Lee, J.; Bruck, D.J.; Walton, V.M.; O’Neal, S.D.; Zalom, F.G. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): Invasive Pest of Ripening Soft Fruit Expanding Its Geographic Range and Damage Potential. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2011, 2, G1–G7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, D.; Molitor, D.; Beyer, M. Natural Compounds for Controlling Drosophila suzukii. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawer, R. Chemical Control of Drosophila suzukii. In Drosophila suzukii Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Giunti, G.; Benelli, G.; Palmeri, V.; Laudani, F.; Ricupero, M.; Ricciardi, R.; Maggi, F.; Lucchi, A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Desneux, N.; et al. Non-Target Effects of Essential Oil-Based Biopesticides for Crop Protection: Impact on Natural Enemies, Pollinators, and Soil Invertebrates. Biol. Control 2022, 176, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddi, K.; Turchen, L.M.; Viteri Jumbo, L.O.; Guedes, R.N.; Pereira, E.J.; Aguiar, R.W.; Oliveira, E.E. Rethinking Biorational Insecticides for Pest Management: Unintended Effects and Consequences. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 2286–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amichot, M.; Joly, P.; Martin-Laurent, F.; Siaussat, D.; Lavoir, A.-V. Biocontrol, New Questions for Ecotoxicology? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 33895–33900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schetelig, M.F.; Lee, K.-Z.; Otto, S.; Talmann, L.; Stökl, J.; Degenkolb, T.; Vilcinskas, A.; Halitschke, R. Environmentally Sustainable Pest Control Options for Drosophila suzukii. J. Appl. Entomol. 2018, 142, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, G.; Mermer, S.; Stockton, D.; Lee, J.; Avosani, S.; Abrieux, A.; Anfora, G.; Beers, E.; Biondi, A.; Burrack, H.; et al. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): A Decade of Research Towards a Sustainable Integrated Pest Management Program. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1950–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruitwagen, A.; Beukeboom, L.W.; Wertheim, B. Optimization of Native Biocontrol Agents, with Parasitoids of the Invasive Pest Drosophila suzukii as an Example. Evol. Appl. 2018, 11, 1473–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daane, K.M.; Wang, X.-G.; Biondi, A.; Miller, B.; Miller, J.C.; Riedl, H.; Shearer, P.W.; Guerrieri, E.; Giorgini, M.; Buffington, M.; et al. First Exploration of Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii in South Korea as Potential Classical Biological Agents. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 89, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgini, M.; Wang, X.-G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.-S.; Hougardy, E.; Zhang, H.-M.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Chen, H.-Y.; Liu, C.-X.; Cascone, P.; et al. Exploration for Native Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii in China Reveals a Diversity of Parasitoid Species and Narrow Host Range of the Dominant Parasitoid. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgini, M.; Rossi Stacconi, M.V.; Pace, R.; Tortorici, F.; Cascone, P.; Formisano, G.; Spiezia, G.; Fellin, L.; Carlin, S.; Tavella, L.; et al. Foraging Behavior of Ganaspis brasiliensis in Response to Temporal Dynamics of Volatile Release by the Fruit Drosophila suzukii Complex. Biol. Control 2024, 195, 105562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeijon, L.M.; Birkhan, J.; Lee, J.C.; Ovruski, S.M.; Garcia, F.R.M. Global Trends in Research on Biological Control Agents of Drosophila suzukii: A Systematic Review. Insects 2025, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Wang, X.; Daane, K.M. Host Preference of Three Asian Larval Parasitoids to Closely Related Drosophila Species: Implications for Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacsoh, B.Z.; Schlenke, T.A. High Hemocyte Load Is Associated with Increased Resistance against Parasitoids in Drosophila suzukii, a Relative of D. melanogaster. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi Stacconi, M.V.; Buffington, M.; Daane, K.M.; Dalton, D.T.; Grassi, A.; Kaçar, G.; Miller, B.; Miller, J.C.; Baser, N.; Ioriatti, C.; et al. Host Stage Preference, Efficacy and Fecundity of Parasitoids Attacking Drosophila suzukii in Newly Invaded Areas. Biol. Control 2015, 84, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shi, M.; Huang, J.; Chen, X. Parasitoid Wasps as Effective Biological Control Agents. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, P.K.; McPherson, A.E.; Kula, R.; Hueppelsheuser, T.; Thiessen, J.; Perlman, S.J.; Curtis, C.I.; Fraser, J.L.; Tam, J.; Carrillo, J.; et al. New Records of Leptopilina, Ganaspis, and Asobara Species Associated with Drosophila suzukii in North America, Including Detections of L. japonica and G. brasiliensis. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2020, 78, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furihata, S.; Matsumura, T.; Hirata, M.; Mizutani, T.; Nagata, N.; Kataoka, M.; Katayama, Y.; Omatsu, T.; Matsumoto, H.; Hayakawa, Y. Characterization of Venom and Oviduct Components of Parasitoid Wasp Asobara japonica. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ideo, S.; Watada, M.; Mitsui, H.; Kimura, M.T. Host Range of Asobara japonica (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a Larval Parasitoid of Drosophilid Flies. Entomol. Sci. 2008, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hogg, B.N.; Hougardy, E.; Nance, A.H.; Daane, K.M. Potential Competitive Outcomes among Three Solitary Larval Endoparasitoids as Candidate Agents for Classical Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii. Biol. Control 2019, 130, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi Stacconi, M.V.; Amiresmaeili, N.; Biondi, A.; Carli, C.; Caruso, S.; Dindo, M.L.; Francati, S.; Gottardello, A.; Grassi, A.; Lupi, D.; et al. Host Location and Dispersal Ability of the Cosmopolitan Parasitoid Trichopria drosophilae Released to Control the Invasive Spotted Wing Drosophila. Biol. Control 2018, 117, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cabrera, J.; Moreno-Carrillo, G.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.A.; Mendoza-Ceballos, M.Y.; Arredondo-Bernal, H.C. Single and Combined Release of Trichopria drosophilae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) to Control Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2019, 48, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-G.; Kaçar, G.; Biondi, A.; Daane, K.M. Foraging Efficiency and Outcomes of Interactions of Two Pupal Parasitoids Attacking the Invasive Spotted Wing Drosophila. Biol. Control 2016, 96, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabert, S.; Allemand, R.; Poyet, M.; Eslin, P.; Gibert, P. Ability of European Parasitoids (Hymenoptera) to Control a New Invasive Asiatic Pest, Drosophila suzukii. Biol. Control 2012, 63, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, A.P.; Scheunemann, T.; Vieira, J.G.A.; Morais, M.C.; Bernardi, D.; Nava, D.E.; Garcia, F.R.M. Effects of Extrinsic, Intraspecific Competition and Host Deprivation on the Biology of Trichopria anastrephae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) Reared on Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2019, 48, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, V.; Ellenbroek, T.; Romeis, J.; Collatz, J. Seasonal and Regional Presence of Hymenopteran Parasitoids of Drosophila in Switzerland and Their Ability to Parasitize the Invasive Drosophila suzukii. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.-J.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Hu, H.-Y. Demographic Potential of the Pupal Parasitoid Trichopria drosophilae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) Reared on Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboka, K.M.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Kimathi, E.; Mutanga, O.; Odindi, J.; Niassy, S.; Mohamed, S.A.; Ekesi, S. A Systematic Methodological Approach to Estimate the Impacts of a Classical Biological Control Agent’s Dispersal at Landscape: Application to Fruit Fly Bactrocera dorsalis and Its Endoparasitoid Fopius arisanus. Biol. Control 2022, 175, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demján, P.; Dreslerová, D.; Kolář, J.; Chuman, T.; Romportl, D.; Trnka, M.; Lieskovský, T. Long Time-Series Ecological Niche Modelling Using Archaeological Settlement Data: Tracing the Origins of Present-Day Landscape. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 141, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, L.E. Ecological Niche Modeling: An Introduction for Veterinarians and Epidemiologists. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 519059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outammassine, A.; Zouhair, S.; Loqman, S. Global Potential Distribution of Three Underappreciated Arboviruses Vectors (Aedes japonicus, Aedes vexans and Aedes vittatus) under Current and Future Climate Conditions. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e1160–e1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Rodríguez, D.; Jiménez-Segura, L.; Rogéliz, C.A.; Parra, J.L. Ecological Niche Modeling as an Effective Tool to Predict the Distribution of Freshwater Organisms: The Case of the Sabaleta brycon henni (Eigenmann, 1913). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Qi, G.; Ma, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, R.; McKirdy, S. Predicting the Potential Geographic Distribution of Bactrocera bryoniae and Bactrocera neohumeralis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in China Using MaxEnt Ecological Niche Modeling. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2072–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, G.; Máca, J.; Bächli, G.; Serra, L.; Pascual, M. First Records of the Potential Pest Species Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Europe. J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 136, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.P.; Kriticos, D.J.; Zachariades, C. Climate Matching Techniques to Narrow the Search for Biological Control Agents. Biol. Control 2008, 46, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-De la O., N.B.; Espinosa-Zaragoza, S.; López-Martínez, V.D.; Hight, S.; Varone, L. Ecological Niche Modeling to Calculate Ideal Sites to Introduce a Natural Enemy: The Case of Apanteles opuntiarum (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) to Control Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in North America. Insects 2020, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepa-Yotto, G.T.; Gouwakinnou, G.N.; Fagbohoun, J.R.; Tamò, M.; Sæthre, M. Horizon Scanning to Assess the Bioclimatic Potential for the Alien Species Spodoptera eridania and Its Parasitoids after Pest Detection in West and Central Africa. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4437–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepa-Yotto, G.T.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Goergen, G.; Subramanian, S.; Kimathi, E.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Flø, D.; Thunes, K.H.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Niassy, S.; et al. Global Habitat Suitability of Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae): Key Parasitoids Considered for Its Biological Control. Insects 2021, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantschner, M.V.; Vega, G.; Corley, J. Modelling the establishment, spread and distribution shifts of Pest. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2019, 65, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.K.; Sim, C.; Severson, D.W.; Kang, D.S. Randon forest analysis of impact of abiotic factors on Culex pipiens and Culex quinquefasciatus occurrence. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 9, 773360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.A.; Dias, N.P.; Gottschalk, M.S.; Garcia, F.R.M.; Nava, D.E. Potential distribution of Bactrocera oleae and the parasitoids Fopius arisanus and Psyttalia concolor, aiming at classical biological control. Biol. Control 2019, 132, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, F.; Kumar, L.; Ahmadi, M. A comparison of absolute performance of different correlative and mechanistic species distribution models in an independent area. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 5973–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2023. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Amiresmaeili, N.; Jucker, C.; Savoldelli, S.; Lupi, D. Understanding Trichopria drosophilae performance in laboratory conditions. Bull. Insectol. 2018, 71, 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Beers, E.H.; Beal, D.; Smytheman, P.; Abram, P.K.; Schmidt-Jefris, R.; Moretti, E.; Daane, K.M.; Looney, C.; Lue, C.-H.; Buffington, M. First Records of Adventive Populations of the Ganaspis brasiliensis and Leptopilina japonica in the United States. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2022, 91, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, P.; Renkema, J.; Fournier, V.; Firlej, A. Ability of Muscidifurax raptorellus and Other Parasitoids and Predators to Control Drosophila suzukii Populations in Raspberries in the Laboratory. Insects 2019, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancheri, M.J.B.; Suárez, L.; Kirschbaun, D.S.; Garcia, F.R.M.; Funes, C.F.; Ovruski, S.M. Natural Parasitism Influences Biological Control Strategies against both Global Invasive Pests Ceratitis capitate (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae), and the Neotropical-Native Pest Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae). Environ. Entomol. 2022, 51, 1120–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Santiago, J.M.; Rodriguez-Leyva, E.; Lomeli-Flores, J.R.; Gonzáles-Cabrera, J. Demographic parameters of Trichopria drosophilae in three host species. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cancino, M.D.; González-Hernández, A.; Gonzáles-Cabrera, J.; Moreno-Carrillo, G.; Sánchez-González, J.A.; Arredondo-bernal, H.C. Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Colima, Mexico. Southwest. Entomol. 2015, 40, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, N.; Hideyuki, M.; Ideo, S.; Watada, M.; Kimura, M.T. Ecological, morphological and molecular studies on Ganaspis individuals (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) attacking Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2013, 48, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, T.I.; Kimura, M.T. Toxicity of venom of Asobara and Leptopilina species to Drosophila species. Physiol. Entomol. 2015, 40, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novkovic, B.; Mitsui, H.; Suwito, A.; Kimura, M.T. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Leptopilina species (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea: Figitidae) attacking frugivorous drosophilid flies in Japan, with description of three new species. Entomol. Sci. 2011, 14, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppato, S.; Grassi, A.; Pedrazzoli, F.; Cristofaro, A.; Ioriatti, C. First Report of Leptopilina japonica in Europe. Insects 2020, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi-Stacconi, M.V.; Grassi, A.; Dalton, D.T.; Miller, B.; Ouantar, M.; Loni, A.; Ioriatti, C.; Walton, V.M.; Anfora, G. First field records of Pachycrepoideus vindemiae as a parasitoid of Drosophila suzukii in European and Oregon small fruit production areas. Entomologia 2013, 1, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Hernández, R.A.; Martínez, F.; Ramírez-Ahuja, M.L.; Sánchez, A.; Rodríguez, D.; Driskell, A.; Buffington, M. The description of an efficient trap for monitoring Drosophila suzukii parasitoids in organic soft fruit crops, and a new record of Ganaspsis brasiliensis (Ilhering) (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) from Michoacan, Mexico. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 2021, 123, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellone, V.; Meier, M.; Cara, C.; Paltrinieri, L.P.; Gugerli, F.; Moretti, M.; Wolf, S.; Collatz, J. Multiscale Determinants Drive Parasitization of Drosophilidae by Hymenopteran Parasitoids in Agricultural Landscapes. Insects 2020, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, W. Surveys of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) and Its Host Fruits and Associated Parasitoids in Northeastern China. Insects 2022, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Pang, L.; Pan, Z.; Li, C.; Shi, M.; Huang, J.; Chen, X. The developmental transcriptome of Trichopria drosophilae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) and insights into cuticular protein genes. CBPD 2019, 29, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, H.; Barve, V.; Chamberlain, S. Spocc: Interface to Species Occurrence Data Sources. Available online: https://docs.ropensci.org/spocc/ (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Hijmans, R.J.; Phillips, S.; Leathwick, J.; Elith, J. Dismo: Species Distribution Modeling. CRAN Contrib. Packages 2010, 2017, 1. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dismo/dismo.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Barbet-Massin, M.; Jiguet, F.; Albert, C.H.; Thuiller, W. Selecting Pseudo—Absences for Species Distribution Models: How, Where and How Many? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, B.; Hamm, N.A.S.; Groen, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Toxopeus, A.G. Where Is Positional Uncertainty a Problem for Species Distribution Modelling? Ecography 2014, 37, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Ebi, K.L.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Riahi, K.; Rothman, D.S.; van Ruijven, B.J.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Birkmann, J.; Kok, K.; et al. The Roads Ahead: Narratives for Shared Socioeconomic Pathways Describing World Futures in the 21st Century. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Their Energy, Land Use, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Implications: An Overview. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alin, A. Multicollinearity. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Keough, M.J. Experimental Designs and Data Analysis for Biologists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-511-07812-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Hadi, A.S. Regression Analysis by Example. In Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780470055465. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A Review of Methods to Deal with It and a Simulation Study Evaluating Their Performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, B.; Araújo, M.B. Sdm: A Reproducible and Extensible R Platform for Species Distribution Modelling. Ecography 2016, 39, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R using the Caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Bischl, B. Tunability: Importance of Hyperparameters of Machine Learning Algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.; Anderson, R.; Schapire, R. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 3–4, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, A.H.; Bell, J.F. A Review of Methods for the Assessment of Prediction Errors in Conservation Presence/Absence Models. Environ. Conserv. 1997, 24, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, O.; Tsoar, A.; Kadmon, R. Assessing the Accuracy of Species Distribution Models: Prevalence, Kappa and the True Skill Statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; Pearson, R.G.; Thuiller, W.; Erhard, M. Validation of Species–Climate Impact Models under Climate Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Newell, G.; White, M. On the selection of thresholds for predicting species occurrence with presence-only data. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 1, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoonm, S.; Lee, W. Application of true skill statistics as a practical method for quantitatively assessing CLIMEX performance. Ecol. Ind. 2023, 146, 109830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeijon, L.M.; Gómez-Llano, J.H.; Robe, L.J.; Ovruski, S.M.; Garcia, F.R.M. Mapping the Potential Presence of the Spotted Wing Drosophila Under Current and Future Scenario: An Update of the Distribution Modeling and Ecological Perspectives. Agronomy 2025, 15, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J. Parasitoids; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780691207025. [Google Scholar]

- Kraaijeveld, A.R.; Van Alphen, J.J.M.; Godfray, H.C.J. The Coevolution of Host Resistance and Parasitoid Virulence. Parasitology 1998, 116, S29–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.N. Coevolution: The Geographic Mosaic of Coevolutionary Arms Races. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, R992–R994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istas, O.; Szűcs, M. Geographic Variation in Resistance of the Invasive Drosophila suzukii to Parasitism by the Biological Control Agent, Ganaspis brasiliensis. Evol. Appl. 2025, 18, e70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovone, A.; Girod, P.; Ris, N.; Weydert, C.; Gibert, P.; Poirié, M.; Gatti, J.L. Worldwide Invasion by Drosophila suzukii: Does Being the “Cousin” of a Model Organism Really Help Setting Up Biological Control? Hopes, Disenchantments And New Perspectives. Rev. D’écologie 2015, 70, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfert, O.; Haye, T.; Weiss, R.; Kriticos, D.; Kuhlmann, U. Modelling the Potential Impact of Climate Change on Future Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Biological Control Agents: Peristenus digoneutis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) as a Case Study. Can. Entomol. 2016, 148, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Khoso, A.G.; Wang, L.; Liu, D. Climate Change Simulations Revealed Potentially Drastic Shifts in Insect Community Structure and Crop Yields in China’s Farmland. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, A.B.; Arteca, E.M.; Newman, J.A. The Impacts of Climate Change on the Abundance and Distribution of the Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) in the United States and Canada. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, G.D.; Emiljanowicz, L.; Wilkinson, F.; Kornya, M.; Newman, J.A. Thermal Tolerances of the Spotted-Wing Drosophila Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ørsted, I.V.; Ørsted, M. Species Distribution Models of the Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii, Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Its Native and Invasive Range Reveal an Ecological Niche Shift. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.A.; Mendes, M.F.; Krüger, A.P.; Blauth, M.L.; Gottschalk, M.S.; Garcia, F.R.M. Global Potential Distribution of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomano, F.Y.; Kasuya, N.; Matsuura, A.; Suwito, A.; Mitsui, H.; Buffington, M.L.; Kimura, M.T. Genetic Differentiation of Ganaspis brasiliensis (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) from East and Southeast Asia. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2017, 52, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, F.; Marchetti, E.; Amiresmaeili, N.; Sacco, D.; Francati, S.; Jucker, C.; Dindo, M.L.; Lupi, D.; Tavella, L. Drosophila Parasitoids in Northern Italy and Their Potential to Attack the Exotic Pest Drosophila suzukii. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 89, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Peterson, A.T. Mapping the Global Distribution of Invasive Pest Drosophila suzukii and Parasitoid Leptopilina japonica: Implications for Biological Control. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, T.D.; Abram, P.K.; Adams, C.; Beal, D.; Beers, E.; Beetle, J.; Biddinger, D.; Brind’Amour, G.; Bruin, A.; Buffington, M.; et al. Widespread Establishment of Adventive Populations of Leptopilina japonica (Hymenoptera, Figitidae) in North America and Development of a Multiplex PCR Assay to Identify Key Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae). NeoBiota 2024, 93, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, J.M.; Wang, X.; Abram, P.K.; Biondi, A.; Buffington, M.L.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Kenis, M.; Lisi, F.; Rossi-Stacconi, M.V.; Seehausen, M.L.; et al. Ganaspis kimorum (Hymenoptera: Figitidae), a Promising Parasitoid for Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2024, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Oliveira, D.; Stupp, P.; Martins, L.N.; Wollmann, J.; Geisler, F.C.S.; Cardoso, T.D.N.; Bernardi, D.; Garcia, F.R.M. Interspecific Competition in Trichopria anastrephae Parasitism (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) Parasitism on Pupae of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Phytoparasitica 2021, 49, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.S.B.; Price, B.E.; Soohoo-Hui, A.; Walton, V.M. Factors Affecting the Biology of Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), a Parasitoid of Spotted-Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioclimatic Variable Code | Description of Each Bioclimatic Variable from WorldClim |

|---|---|

| BIO2 | Mean Diurnal Range [Mean of monthly (max temp-max temp)] |

| BIO5 | Max Temperature of Warmest Month |

| BIO6 | Min Temperature of Coldest Month |

| BIO7 | Temperature Annual Range (BIO5-BIO6) |

| BIO8 | Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter |

| BIO9 | Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter |

| BIO10 | Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter |

| BIO11 | Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter |

| BIO12 | Annual Precipitation |

| BIO13 | Precipitation of Wettest Month |

| BIO14 | Precipitation of Driest Month |

| BIO15 | Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation) |

| BIO16 | Precipitation of Wettest Quarter |

| BIO17 | Precipitation of Driest Quarter |

| BIO18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter |

| BIO19 | Precipitation of Coldest Quarter |

| Parasitoid | Known Occurrence Points | Bioclimatic Variables Contribution | AUC Mean | TSS | Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptopilina japonica | 41 | BIO2, BIO3, BIO5, BIO8, BIO9, BIO14, BIO15, BIO18, BIO19 | 0.988 ± 0.020 | 0.518 | 0.264 |

| Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae | 63 | BIO2, BIO8, BIO9, BIO10, BIO15, BIO18, BIO19 | 0.981 ± 0.026 | 0.530 | 0.283 |

| Trichopria drosophilae | 47 | BIO2, BIO5, BIO7, BIO8, BIO9, BIO12, BIO13, BIO19 | 0.971 ± 0.048 | 0.550 | 0.245 |

| Bioclimatic Variables | Leptopilina japonica (%) | Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae (%) | Trichopria drosophilae (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIO2 | 13.2 | 5.4 | 24.6 |

| BIO5 | - | - | 9.6 |

| BIO7 | - | - | 6.3 |

| BIO8 | - | 13.2 | 5.8 |

| BIO9 | - | 18.1 | 15.6 |

| BIO10 | 7.2 | 21.6 | - |

| BIO11 | 28.5 | - | - |

| BIO12 | - | - | 18.5 |

| BIO13 | 32.0 | - | 11.1 |

| BIO14 | 9.7 | - | - |

| BIO15 | 2.0 | 10.4 | - |

| BIO16 | - | - | - |

| BIO17 | - | - | - |

| BIO18 | 7.4 | 8.7 | - |

| BIO19 | - | 22.7 | 8.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abeijon, L.M.; Gómez-Llano, J.H.; Ovruski, S.M.; Garcia, F.R.M. Global Distribution of Three Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae): Present and Future Climate Change Scenarios. Insects 2026, 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010012

Abeijon LM, Gómez-Llano JH, Ovruski SM, Garcia FRM. Global Distribution of Three Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae): Present and Future Climate Change Scenarios. Insects. 2026; 17(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbeijon, Lenon Morales, Jesús Hernando Gómez-Llano, Sergio Marcelo Ovruski, and Flávio Roberto Mello Garcia. 2026. "Global Distribution of Three Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae): Present and Future Climate Change Scenarios" Insects 17, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010012

APA StyleAbeijon, L. M., Gómez-Llano, J. H., Ovruski, S. M., & Garcia, F. R. M. (2026). Global Distribution of Three Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae): Present and Future Climate Change Scenarios. Insects, 17(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010012