The Diversity of Spoon-Winged and Thread-Winged Lacewing Larvae Today and in Deep Time—An Expanded View

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Imaging and Documentation

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Outlines

2.5. Shape Analysis

3. Results

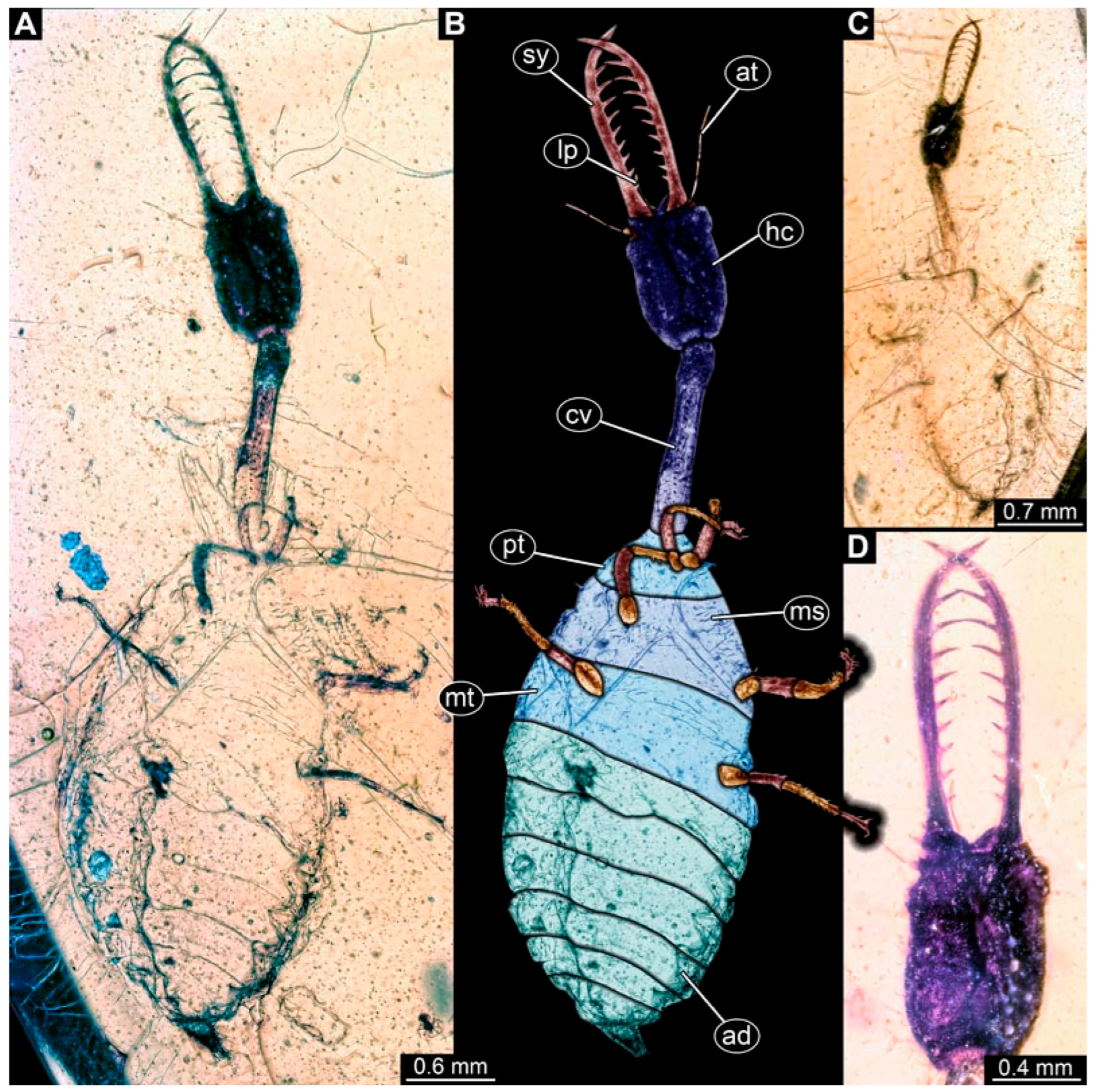

3.1. Descriptions of New Fossil Larvae: Possible Larvae of Crocinae

3.2. Descriptions of New Fossil Larvae: Possible Larvae of Nemopterinae

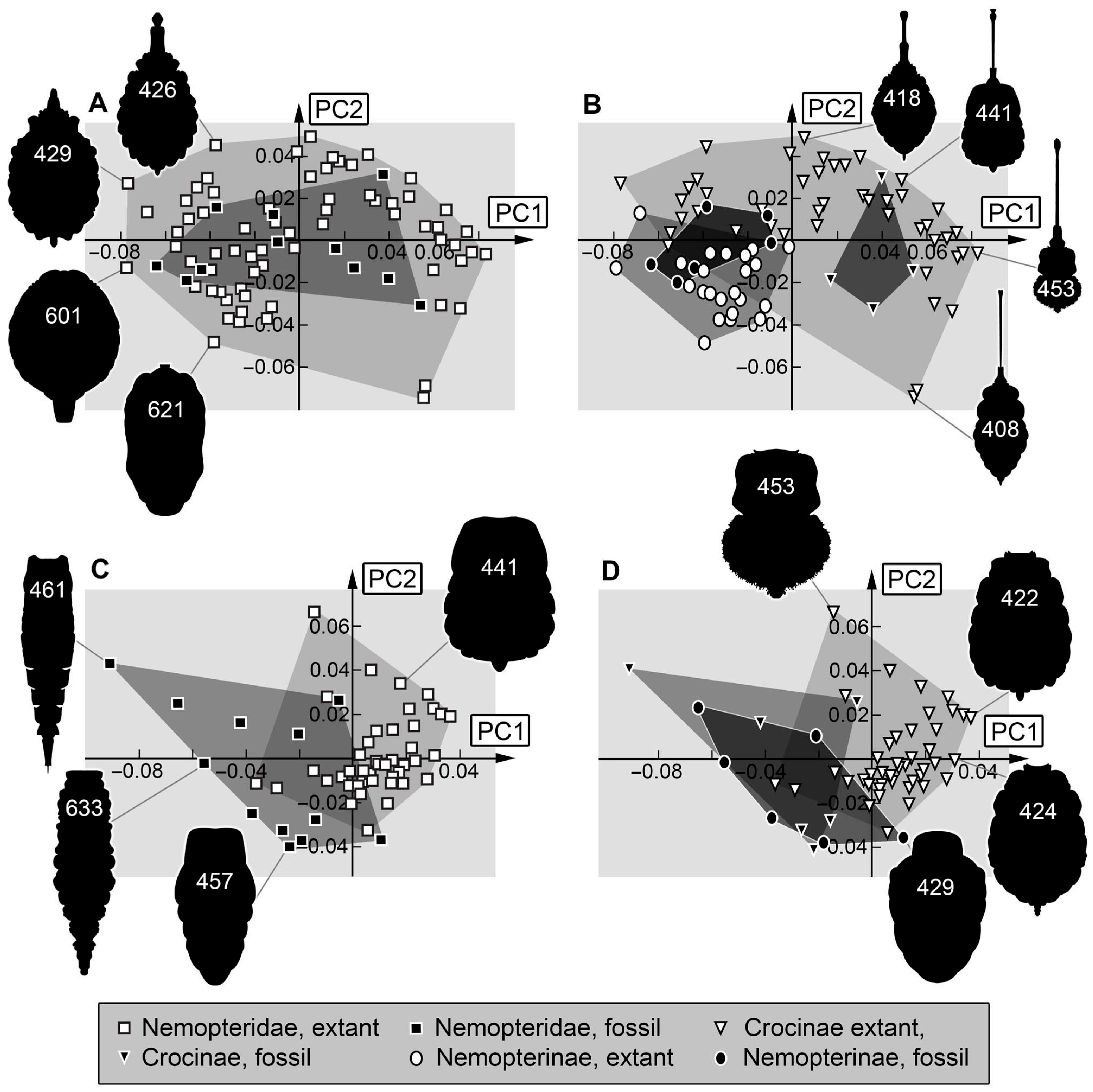

3.3. Shape Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Identity of the Long-Necked Specimens (0471–0482)

4.2. Identity of the Other Specimens (0630–0633, 0901)

4.3. Shape over Time

4.4. Expanding of Morphospace by Adding New Specimens

4.5. Mosaic and Convergent Evolution

4.6. Convergent Evolution Is Not a Problem, but a Chance

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dunn, R.R. Modern insect extinctions, the neglected majority. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, C.A.; Sorg, M.; Jongejans, E.; Siepel, H.; Hofland, N.; Schwan, H.; Stenmans, W.; Müller, A.; Sumser, H.; Hörren, T.; et al. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, C.A.; Ssymank, A.; Sorg, M.; de Kroon, H.; Jongejans, E. Insect biomass decline scaled to species diversity: General patterns derived from a hoverfly community. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2002554117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, R.E.; Grooten, M.; Peterson, T. Living Planet Report 2020—Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, D.; Engel, M.S. Evolution of the Insects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; p. 755. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.-Q. Animal biodiversity: An introduction to higher-level classification and taxonomic richness. Zootaxa 2011, 3148, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Q. Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity. Zootaxa 2013, 3703, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, D.D.; Shin, S.; Ahrens, D.; Balke, M.; Beza-Beza, C.; Clarke, D.J.; Donath, A.; Escalona, H.E.; Friedrich, F.; Letsch, H.; et al. The evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24729–24737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, D.D.; Wild, A.L.; Kanda, K.; Bellamy, C.L.; Beutel, R.G.; Caterino, M.S.; Farnum, C.W.; Hawks, D.C.; Ivie, M.A.; Jameson, M.L.; et al. The beetle tree of life reveals that Coleoptera survived end-Permian mass extinction to diversify during the Cretaceous terrestrial revolution. Syst. Entomol. 2015, 40, 835–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudinot, B.E.; Yan, E.V.; Prokop, J.; Luo, X.Z.; Beutel, R.G. Permian parallelisms: Reanalysis of †Tshekardocoleidae sheds light on the earliest evolution of the Coleoptera. Syst. Entomol. 2023, 48, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, D.K.; Wiegmann, B.M.; Courtney, G.W.; Meier, R.; Lambkin, C.; Pape, T. Phylogeny and systematics of Diptera: Two decades of progress and prospects. Zootaxa 2007, 1668, 565–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, G.W.; Pape, T.; Skevington, J.H.; Sinclair, B.J. Chapter 9 Biodiversity of Diptera. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society; Footit, R.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 229–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M. Typical flies: Natural history, lifestyle and diversity of Diptera. In Life Cycle and Development of Diptera; Sarwar, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.T. Chapter 12 Biodiversity of Hymenoptera. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society; Footit, R.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 419–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.S.; Krogmann, L.; Mayer, C.; Donath, A.; Gunkel, S.; Meusemann, K.; Kozlov, A.; Podsiadlowski, L.; Petersen, M.; Lanfear, R.; et al. Evolutionary history of the Hymenoptera. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, L.; Shih, C.; Gao, T.; Ren, D. Chapter 22 Hymenoptera—Sawflies and Wasps. In Rhythms of Insect Evolution; Ren, D., Shih, C.K., Gao, T., Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 426–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, P.Z. Chapter 13 Diversity and significance of Lepidoptera: A phylogenetic perspective. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society; Footit, R.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 463–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, C.; Davis, D.R.; Cummings, M.P. Phylogeny and evolution of Lepidoptera. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, R.G.; Friedrich, F.; Yang, X.-K.; Ge, S.-Q. Insect Morphology and Phylogeny: A Textbook for Students of Entomology; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.S.; Winterton, S.L.; Breitkreuz, L.C. Phylogeny and evolution of Neuropterida: Where have wings of lace taken us? Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspöck, U.; Aspöck, H. Verbliebene Vielfalt vergangener Blüte. Zur Evolution, Phylogenie und Biodiversität der Neuropterida (Insecta: Endopterygota). Denisia 2007, 20, 451–516. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, J.D. Neuropterida Species of the World; Lacewing Digital Library, Research Publication: College Station, TX, USA, 2018; Volume 1, Available online: https://lacewing.tamu.edu/SpeciesCatalog/Main (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Haug, C.; Braig, F.; Haug, J. Quantitative analysis of lacewing larvae over more than 100 million years reveals a complex pattern of loss of morphological diversity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, E.G. A Comparative Morphological Study of the Head Capsule and Cervix of Larval Neuroptera (Insecta). Ph.D thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964; p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Aspöck, U.; Aspöck, H. Kamelhälse, Schlammfliegen, Ameisenlöwen. Wer sind sie? (Insecta: Neuropterida: Raphidioptera, Megaloptera, Neuroptera). Stapfia 1999, 60, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, D.; Randolf, S.; Aspöck, U. Chapter 11: From chewing to sucking via phylogeny—From sucking to chewing via ontogeny: Mouthparts of Neuroptera. In Insect Mouthparts: Form, Function, Development and Performance; Krenn, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 361–385. [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat, V.J. Nuevos datos sobre algunas especies de Nemopteridae y Crocidae (Insecta: Neuroptera). Heteropterus Rev. Entomol. 2008, 8, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, E.J. Die Larve von Nemoptera coa (Linnaeus, 1758) (Neuropteroidea, Planipennia). Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 1993, 40, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Flórez, A.F.; Haug, C.; Burmeister, E.-G.; Haug, J.T. A neuropteran insect with the relatively longest prothorax: The “giraffe” among insects is the larva of a Necrophylus species from Libya. Spixiana 2020, 43, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, F.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, G.; Wang, B. Amber: Life Through Time and Space; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.W. Frozen Dimensions. The Fossil Insects and Other Invertebrates in Amber; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2017; p. 692. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, C.; Herrera-Flórez, A.F.; Müller, P.; Haug, J.T. Cretaceous chimera—An unusual 100-million-year old neuropteran larva from the “experimental phase” of insect evolution. Palaeodiversity 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, G.T.; Baranov, V.; Wizen, G.; Pazinato, P.G.; Müller, P.; Haug, C.; Haug, J.T. The morphological diversity of long-necked lacewing larvae (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontiformia). Bull. Geosci. 2021, 96, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, G.T.; Haug, C.; Haug, J.T. The morphological diversity of spoon-winged lacewing larvae and the first possible fossils from 99 million-year-old Kachin amber, Myanmar. Palaeodiversity 2021, 14, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, J.L.F.P. Lettre relative à divers Coquilles, Crustacés. Insectes, Reptiles et Oiseaux, observés en Égypte; adressée par M. Roux à M. le Baron de Férussac. Ann. Sci. Nat. 1833, 28, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, A.; Suludere, Z.; Candan, D.; Canbulat, S. Morphology and surface structure of eggs and first instar larvae of Croce schmidti (Navás, 1927) (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). Zootaxa 2007, 1554, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaum, H.R. Necrophilus arenarius Roux, die muthmassliche Larve von Nemoptera. Berl. Entomol. Z. 1857, 1, 1–9 + Taf. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, C.C. XXVII. Entomological notes. Croce filipennis, Westw. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1910, 20, 530–532 + 1 pl. [Google Scholar]

- Imms, A.D.X. Contributions to a knowledge of the structure and biology of some Indian Insects.-I. On the life-history of Croce filipennis, Westw. (Order Neuroptera, Fam. Hemerobiidæ). Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1911, 11, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, A.D. A General Textbook of Entomology; Methuen & Co.: London, UK, 1923; p. 736. [Google Scholar]

- Eltringham, H. On the larva of Pterocroce storeyi, With. (Nemopteridae). Trans. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 1923, 71, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withycombe, C.L. XIII. Systematic notes on the Crocini (Nemopteridae), with descriptions of new genera and species. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1923, 71, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, F. Morphologie, milieu biologique et comportement de trois Crocini nouveaux du Sahara nord-occidental (Planipennes, Nemopteridae). Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 1952, 119, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, E.F. Neuroptera (Lacewings). In Insects of Australia: A Textbook for Students and Research Workers; CSIRO, Ed.; Melbourne University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1970; pp. 472–494. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. The larva of Laurhervasia setacea (Klug), (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae: Crocinae) from southern Africa. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1976, 39, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. A new genus and species in the Crocinae (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) from Southern Africa. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1977, 40, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. The Crocinae of southern Africa (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). 1. The genera Laurhervasia Navás and Thysanocroce Withycombe. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1980, 43, 341–365. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. The Crocinae of southern Africa (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). 2. The genus Concroce Tjeder. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1981, 44, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. The Crocinae of southern Africa (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). 3. The genus Tjederia Mansell, with keys to the southern African Crocinae. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1981, 44, 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. A revision of the Australian Crocinae (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). Aust. J. Zool. 1983, 31, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansell, M.W. New Crocinae (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) from South America, with descriptions of larvae. J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1983, 46, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat, V.J. Pterocroce capillaris (Klug, 1836) en Europa (Neur., Plan., Nemopteridae). Neuroptera Intern. 1983, 2, 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat, V.J. Estadios larvarios de los neurópteros ibéricos I: Josandreva sazi (Neur. Plan., Nemopteridae). Speleon 1983, 26, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel, H. Die Nemopteriden (Fadenhafte) Arabiens. Stapfia 1999, 60, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Aspöck, H.; Aspöck, U. Another neuropterological field trip to Morocco. Lacewing News 2014, 19, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Suludere, Z.; Satar, A.; Candan, S.; Canbulat, S. Morphology and surface structure of eggs and first instar larvae of Dielocroce baudii (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) from Turkey. Entomol. News 2006, 117, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusun, S.; Satar, A. Morphology, surface structure and sensory receptors of larvae of Dielocroce ephemera (Gerstaecker, 1894) (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). Entomol. News 2016, 126, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, D.; Engel, M.S.; Basso, A.; Wang, B.; Cerretti, P. Diverse Cretaceous larvae reveal the evolutionary and behavioural history of antlions and lacewings. Nat. Comm. 2018, 9, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.B.; Stange, L.A. A new species of Moranida Mansell from Venezuela (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae). Insecta Mundi 1989, 3, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Navás, L. Once Neurópteros nuevos españoles. Bol. Soc. Entomol. Esp. 1919, 2, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Withycombe, C.L. XV. Some aspects of the biology and morphology of the Neuroptera. With special reference to the immature stages and their possible phylogenetic significance. Trans. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 1925, 72, 303–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, W.H. Some notes on the spoon-winged lacewing (Chasmoptera hutti). West. Aust. Nat. 1947, 1, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. The first record of a larval nemopterid from southern Africa (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae: Nemopterinae). J. Entomol. Soc. S. Afr. 1973, 36, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, M.W. Unique morphological and biological attributes: The keys to success in Nemopteridae (Insecta: Neuroptera). In Pure and Applied Research in Neuropterology, Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Neuropterology, 2–6 May 1994, Cairo, Egypt; Canard, M., Aspöck, H., Mansell, M.W., Eds.; Privately Printed: Toulouse, France, 1996; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.B.; Stange, L.A. A new species of Stenorrhachus McLachlan from Chile (Neuroptera: Nemopteridae) with biological notes. Insecta Mundi 2012, 226, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat, V.J. Larval stages of European Nemopterinae, with systematic considerations on the family Nemopteridae (Insecta, Neuroptera). Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 1996, 43, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, D.; Aspöck, U.; Aspöck, H.; Cerretti, P. Phylogeny of Myrmeleontiformia based on larval morphology (Neuropterida: Neuroptera). Syst. Entomol. 2017, 42, 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Meth. 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.; Haug, G.T.; Zippel, A.; van der Wal, S.; Haug, J.T. The earliest record of fossil solid-wood-borer larvae—Immature beetles in 99 million-year-old Myanmar amber. Palaeoentomology 2021, 004, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, H.; Ukai, Y. SHAPE: A computer program package for quantitative evaluation of biological shapes based on elliptic Fourier descriptors. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braig, F.; Haug, J.T.; Schädel, M.; Haug, C. A new thylacocephalan crustacean from the Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones of southern Germany and the diversity of Thylacocephala. Palaeodiversity 2019, 12, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Bonhomme, V.; Picq, S.; Gaucherel, C.; Claude, J. Momocs: Outline analysis using R. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 56, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepp, J. Erforschungsstand der Neuropteren. Larven der Erde (mit einem Schlüssel zur Larvaldiagnose der Familien, einer Übersicht von 340 beschriebenen Larven und 600 Literaturzitaten). In Progress in World’s Neuropterology; Gepp, J., Aspöck, H., Hölzel, H., Eds.; The Symposium: Graz, Austria, 1984; pp. 183–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tjeder, B. Neuroptera-Planipennia. The lacewings of Southern Africa. 6. Family Nemopteridae. In South African Animal Life, 13; Hanström, B., Brinck, P., Rudebec, G., Eds.; Swedish Natural Science Research Council: Stockholm, Sweden, 1967; pp. 290–501. [Google Scholar]

- Braig, F.; Popp, T.; Zippel, A.; Haug, G.T.; Linhart, S.; Müller, P.; Weiterschan, T.; Haug, J.T.; Haug, C. The diversity of larvae with multi-toothed stylets from about 100 million years ago illuminates the early diversification of antlion-like lacewings. Diversity 2023, 15, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarkin, V.N. Re-description of Grammapsychops lebedevi Martynova, 1954 (Neuroptera: Psychopsidae) with notes on the Late Cretaceous psychopsoids. Zootaxa 2018, 4524, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, J.T.; Müller, P.; Haug, C. A 100-million-year old slim insectan predator with massive venom-injecting stylets-a new type of neuropteran larva from Burmese amber. Bull. Geosci. 2019, 94, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.P.; Gombos, D.; Haug, G.T.; Haug, C.; Gauweiler, J.; Hörnig, M.K.; Haug, J.T. Expanding the fossil record of soldier fly larvae—An important component of the Cretaceous amber forest. Diversity 2023, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenbach, C.; Buchner, L.; Haug, G.T.; Haug, C.; Haug, J.T. An Expanded View on the Morphological Diversity of Long-Nosed Antlion Larvae Further Supports a Decline of Silky Lacewings in the Past 100 Million Years. Insects 2023, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchner, L.; Linhart, S.; Braig, F.; Haug, G.T.; Weiterschan, T.; Haug, C.; Haug, J.T. New data indicate larger decline in morphological diversity in split-footed lacewing larvae than previously estimated. Insects 2025, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, R.M.; Schweitzer, C.E. Is Eocarcinus Withers, 1932, a basal brachyuran? J. Crustac. Biol. 2010, 30, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, J.T.; Haug, C. Eoprosopon klugi (Brachyura)—The oldest unequivocal and most “primitive” crab reconsidered. Palaeodiversity 2014, 7, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz, G. Eocarcinus praecursor Withers, 1932 (Malacostraca, Decapoda, Meiura) is a stem group brachyuran. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2020, 59, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.; Zippel, A.; Müller, P.; Haug, J.T. Unusual larviform beetles in 100-million-year-old Kachin amber resemble immatures of trilobite beetles and fireflies. PalZ 2023, 97, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippel, A.; Kiesmüller, C.; Haug, G.T.; Müller, P.; Weiterschan, T.; Haug, C.; Hörnig, M.K.; Haug, J.T. Long-headed predators in Cretaceous amber—Fossil findings of an unusual type of lacewing larva. Palaeoentomology 2021, 004, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.; Posada Zuluaga, V.; Zippel, A.; Braig, F.; Müller, P.; Gröhn, C.; Weiterschan, T.; Wunderlich, J.; Haug, G.T.; Haug, J.T. The morphological diversity of antlion larvae and their closest relatives over 100 million years. Insects 2022, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechly, G. Fossil Friday: Cretaceous Insect Chimera Illustrates a Design Principle. Evolution News & Science Today. 2023. Available online: https://scienceandculture.com/2023/12/fossil-friday-a-cretaceous-insect-chimera-illustrates-a-design-principle/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Haug, C.; Haug, J.T. A new fossil mantis shrimp and the convergent evolution of a lobster-like morphotype. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhee, G.R. Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; p. 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.; Haug, G.T.; Kiesmüller, C.; Haug, J.T. Convergent evolution and convergent loss in the grasping structures of immature earwigs and aphidlion-like larvae as demonstrated by about 100-million-year-old fossils. Swiss J. Palaeontol. 2023, 142, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, G.T.; Haug, J.T.; Haug, C. Convergent evolution of defensive appendages—A lithobiomorph-like centipede with a scolopendromorph-type ultimate leg from about 100 million-year-old amber. Palaeobiodivers. Palaeoenviron 2024, 104, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, J.T.; Audo, D.; Charbonnier, S.; Haug, C. Diversity of developmental patterns in achelate lobsters—Today and in the Mesozoic. Dev. Genes Evol. 2013, 223, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Buchner, L.; Linhart, S.; Haug, G.T.; Braig, F.; Weiterschan, T.; Müller, P.; Haug, J.T.; Haug, C. The Diversity of Spoon-Winged and Thread-Winged Lacewing Larvae Today and in Deep Time—An Expanded View. Insects 2026, 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010011

Buchner L, Linhart S, Haug GT, Braig F, Weiterschan T, Müller P, Haug JT, Haug C. The Diversity of Spoon-Winged and Thread-Winged Lacewing Larvae Today and in Deep Time—An Expanded View. Insects. 2026; 17(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuchner, Laura, Simon Linhart, Gideon T. Haug, Florian Braig, Thomas Weiterschan, Patrick Müller, Joachim T. Haug, and Carolin Haug. 2026. "The Diversity of Spoon-Winged and Thread-Winged Lacewing Larvae Today and in Deep Time—An Expanded View" Insects 17, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010011

APA StyleBuchner, L., Linhart, S., Haug, G. T., Braig, F., Weiterschan, T., Müller, P., Haug, J. T., & Haug, C. (2026). The Diversity of Spoon-Winged and Thread-Winged Lacewing Larvae Today and in Deep Time—An Expanded View. Insects, 17(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010011