Farmers’ Perception of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) as an Invasive Pest and Its Management

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

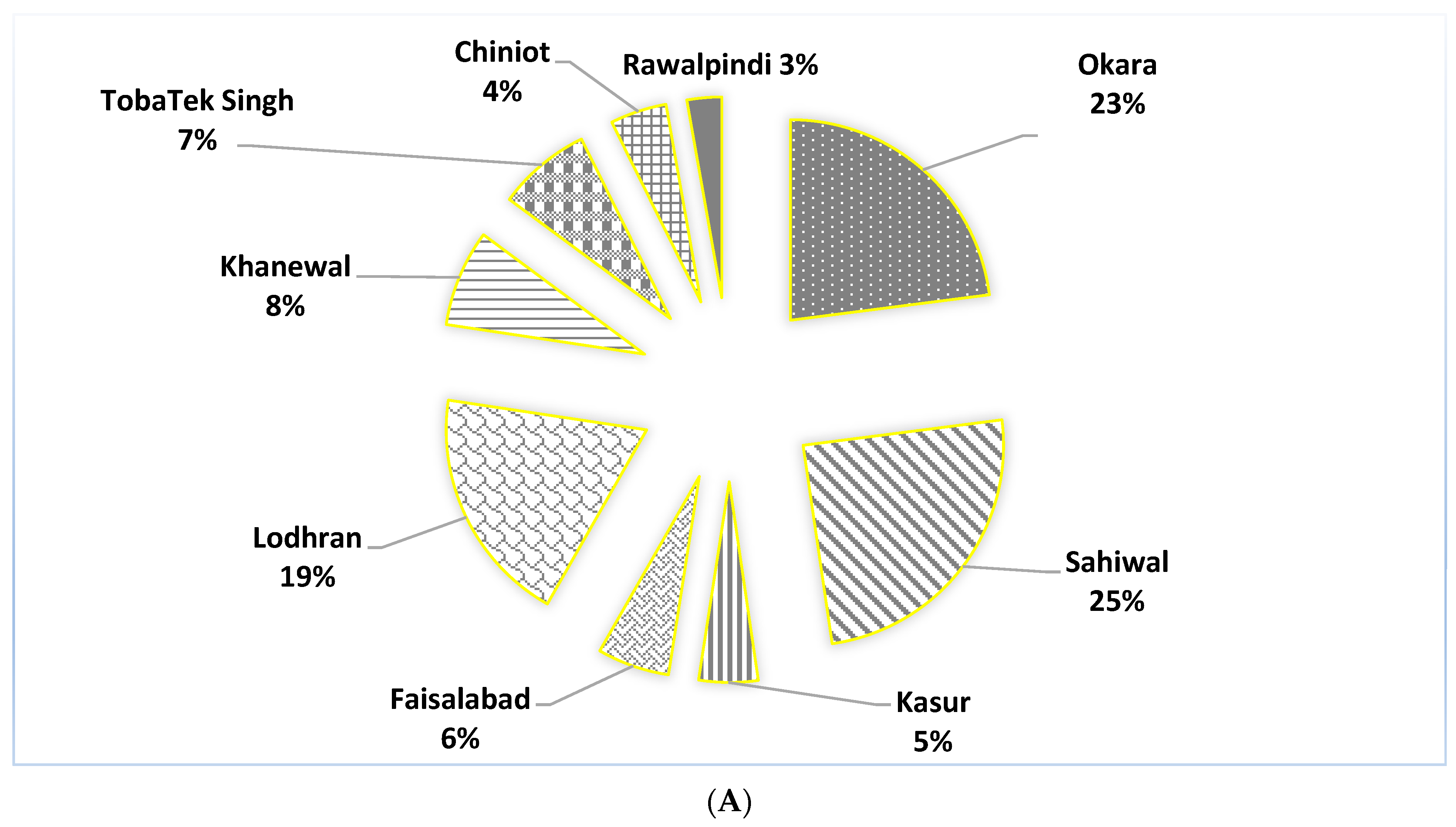

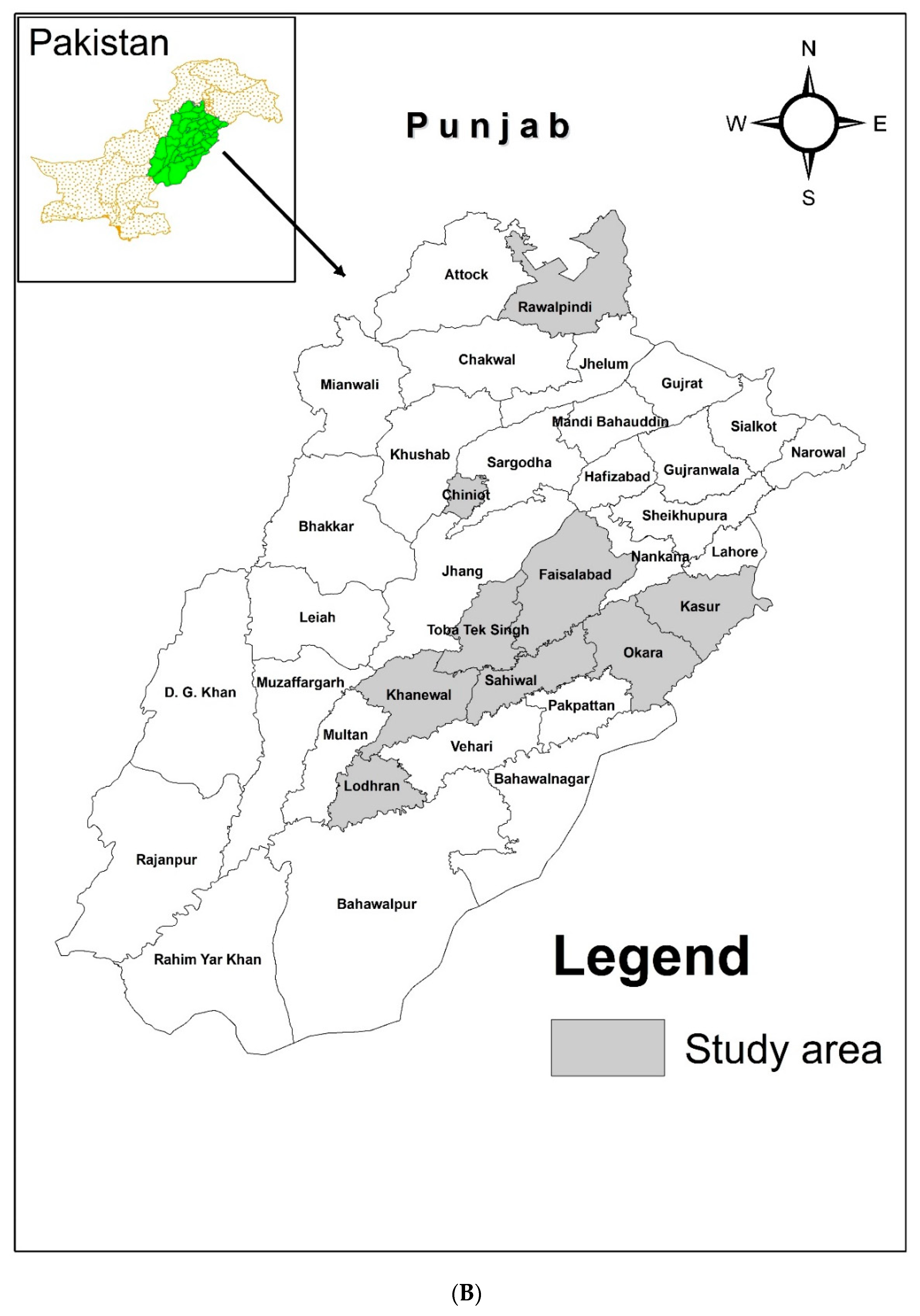

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey Tools

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Farmers

3.2. Maize Crop Cultivation

3.3. Awareness of Maize Insect Pests, Their Management Practices and Sources of Information

3.3.1. Awareness of Maize Insect Pest and Their Management Practices

3.3.2. Source of Agricultural Information

3.4. Awareness of FAW Identification and Damage

3.5. Farmers’ Perception of FAW

3.6. Farmers’ Perception About Maize Crop Interaction with FAW

3.7. Previous Year Attack Intensity and Its Management

3.8. Multinomial Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kenis, M.; Benelli, G.; Biondi, A.; Calatayud, P.A.; Day, R.; Desneux, N.; Harrison, R.D.; Kriticos, D.; Rwomushana, I.; Van den Berg, J.; et al. Invasiveness, biology, ecology, and management of the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 43, 187–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlinda, S.; Simbolon, I.M.P.; Hasbi; Suwandi, S. Suparman Host plant species of the new invasive pest, Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in South Sumatra. In Proceedings of the Sriwijaya Conference on Sustainable Environment, Agriculture, and Farming System, Palembang, Indonesia, 29 September 2021; IOP Publishing: Palembang, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckhuys, K.A.G.; Akutse, K.S.; Amalin, D.M.; Araj, S.E.; Barrera, G.; Beltran, M.J.B.; Ben Fekih, I.; Calatayud, P.A.; Cicero, L.; Cokola, M.C.; et al. Global scientific progress and shortfalls in biological control of the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Biol. Control. 2024, 191, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyebi, A.; Otim, M.H.; Walsh, T.; Tay, W.T. Farmer perception of impacts of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith) and transferability of its management practices in Uganda. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2023, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Jin, D.C.; Hou, J.T.; Liu, X. Effects of three different host plants on two sex life table parameters of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudron, F.; Zaman-Ullah, M.A.; Chaipa, I.; Chari, N.; Chinwada, P. Understanding the factors influencing fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith) damage in African smallholder maize fields and quantifying its impact on yield. A case study in Eastern Zimbabwe. Crop Prot. 2019, 120, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, B.; Simiyu, J.; Mendesil, E.; Likhayo, P.; Ayalew, G.; Mohamed, S.; Subramanian, S.; Tefera, T. Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda infestations in East Africa: Assessment of damage and parasitism. Insects 2019, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, H.; Kimenju, S.C.; Munyua, B.; Palmas, S.; Kassie, M.; Bruce, A. Spread and impact of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith) in maize production areas of Kenya. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 292, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, I.G.; Tampaa, F.; Tetteh, B.K.D. Farmers control strategies against Fall Armyworm and determinants of implementation in two districts of the upper west region of Ghana. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2024, 70, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjorin, F.B.; Odeyemi, O.O.; Akinbode, O.A.; Kareem, K.T. Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) infestation: Maize yield depression and physiological basis of tolerance. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2022, 62, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bakry, M.; Abdel-Baky, N.F. Impact of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) infestation on maize growth characteristics and yield loss. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 84, e274602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Rwomushana, I.; Mugambi, I. Fall Armyworm invasion in Sub-Saharan Africa and impacts on community sustainability in the wake of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Reviewing the evidence. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 62, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niassy, S.; Omuse, E.R.; Khangati, J.E.; Bachinger, I.; Kupesa, D.M.; Cheseto, X.; Mbatha, B.W.; Copeland, R.S.; Mohamed, S.A.; Gama, M.; et al. Validating indigenous farmers’ practice in the management of the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) in maize cropping systems in Africa. Life 2024, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, K.; Maino, J.L.; Day, R.; Umina, P.A.; Bett, B.; Carnovale, D.; Ekesi, S.; Meagher, R.; Reynolds, O.L. Global crop impacts, yield losses and action thresholds for Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda): A review. Crop Prot. 2021, 145, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirenda, H.; Mwangomba, W.; Nyirenda, E.M. Delving into possible missing links for attainment of food security in Central Malawi: Farmers’ perceptions and long-term dynamics in maize (Zea mays L.) production. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Aleem, A.; Manzoor, F.; Ahmad, S.; Anwar, H.M.Z.; Aroob, T.; Ahmad, M. Mortality dynamics of exotic Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 7, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouh, N.Y.; Khugaev, C.V.; Utkina, A.O.; Isaev, K.V.; Mohamed, E.S.; Kucher, D.E. Contribution of Eco-Friendly Agricultural Practices in Improving and Stabilizing Wheat Crop Yield: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Growth. Annual Reports. 2022. Available online: https://www.sbp.org.pk/reports/annual/aarFY22/Chapter-02.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Naeem-Ullah, U.; Ansari, M.A.; Iqbal, N.; Saeed, S. First Authentic Report of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera), an Alien Invasive Species from Pakistan. Appl. Sci. Bus. Econ. 2019, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Gilal, A.A.; Bashir, L.; Faheem, M.; Rajput, A.; Soomro, J.A.; Kunbhar, S.; Sahito, J.G.M. First record of invasive Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)) in corn fields of Sindh, Pakistan. Pak. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 33, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji-Hedfi, L.; Rhouma, A.; Hajlaoui, H.; Hajlaoui, F.; Rebouh, N.Y. Understanding the influence of applying two culture filtrates to control gray mold disease (Botrytis cinerea) in tomato. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi, D.; Kyerematen, R.; Eziah, V.Y.; Osei-Mensah, Y.O.; Afreh-Nuamah, K.; Aboagye, E.; Osae, M.; Meagher, R.L. Assessment of impacts of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), on maize production in Ghana. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houngbo, S.; Zannou, A.; Aoudji, A.; Sossou, H.C.; Sinzogan, A.; Sikirou, R.; Zossou, E.; Totin Vodounon, H.S.; Adomou, A.; Ahanchede, A. Farmers’ knowledge and management practices of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith), in Benin, West Africa. Agriculture 2020, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odong, T.L.; Obongo, I.; Ariong, R.; Adur, S.E.; Adumo, S.A.; Onen, D.O.; Rwotonen, B.I.; Otim, M.H. Farmer perceptions, knowledge, and management of Fall Armyworm in maize production in Uganda. Front. Insect Sci. 2024, 4, 1345139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakistan Meterological Department. 2022. Available online: https://www.pmd.gov.pk/en/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Akhtar, S.; Ullah, R.; Nazir, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Raza, M.H.; Iqbal, N.; Faisal, M. Factors influencing hybrid maize farmers’ risk attitudes and their perceptions in Punjab province, Pakistan. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abro, Z.; Kimathi, E.; De Groote, H.; Tefera, T.; Sevgan, S.; Niassy, S.; Kassie, M. Socioeconomic and health impacts of Fall Armyworm in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongnaa, C.A.; Bakang, J.E.A.; Asiamah, M.; Appiah, P.; Asibey, J.K. Adoption and compliance with council for scientific and industrial research recommended maize production practices in Ashanti region, Ghana. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 18, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, J.A.; Kansiime, M.K.; Rwomushana, I.; Mugambi, I.; Nunda, W.; Mloza Banda, C.; Nyamutukwa, S.; Makale, F.; Day, R. Impact of Fall Armyworm invasion on household income and food security in Zimbabwe. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, H.; Schlemmer, M.L.; Van den Berg, J. The effect of temperature on the development of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects 2020, 11, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canico, A.; Mexia, A.; Santos, L. Farmers’ knowledge, perception and management practices of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda Smith) in Manica province, Mozambique. NeoBiota 2021, 68, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safo, A.; Avicor, S.W.; Baidoo, P.K.; AddoFordjour, P.; Ainooson, M.K.; Osae, M.; Gyan, S.E.; Nboyine, J.A. Farmers’ knowledge, experience, and management of Fall Armyworm in a major maize producing municipality in Ghana. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2184006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, H.; Raza, M.H.; Faisal, M.; Nadeem, N.; Khan, N.; Kassem, H.S.; Elhindi, K.M.; Mahmood, S. Does Farm Mechanization Improve Farm Performance and Ensure Food Availability at Household Level? Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1453221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.Z.A.; Paudel, S.; Saeed, S.; Ali, M.; Hussain, S.B.; Ranamukhaarachchi, S.L. Mitigating the impact of the invasive Fall Armyworm: Evidence from South Asian farmers and policy recommendations. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Mugambi, I.; Rwomushana, I.; Nunda, W.; Lamontagne-Godwin, J.; Rware, H.; Phiri, N.A.; Chipabika, G.; Ndlovu, M.; Day, R. Farmer perception of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiderda J.E. Smith) and farm-level management practices in Zambia. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2840–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makale, F.; Mugambi, I.; Kansiime, M.K.; Yuka, I.; Abang, M.; Lechina, B.S.; Rampeba, M.; Rwomushana, I. Fall Armyworm in Botswana: Impacts, farmer management practices and implications for sustainable pest management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwenyama, P.; Siziba, S.; Nyanga, L.K.; Stathers, T.E.; Mubayiwa, M.; Mlambo, S.; Nyabako, T.; Bechoff, A.; Shee, A.; Mvumi, B.M. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ maize grain storage protection practices and understanding of the nutritional aspects of grain postharvest losses. Food Secur. 2023, 15, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, S.K.; Sanchez, M.V.; Bertini, R. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Dev. 2021, 142, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, J.A.; Kansiime, M.K.; Mugambi, I.; Rwomushana, I.; Kenis, M.; Day, R.K.; Lamontagne-Godwin, J. Understanding smallholders’ responses to Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) invasion: Evidence from five African countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istriningsih; Dewi, Y.A.; Yulianti, A.; Hanifah, V.W.; Jamal, E.; Dadang; Sarwani, M.; Mardiharini, M.; Anugrah, I.S.; Darwis, V.; et al. Farmers’ knowledge and practice regarding good agricultural practices (GAP) on safe pesticide usage in Indonesia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: Trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, F.; Ayalew, D. Status and control measures of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) infestations in maize fields in Ethiopia: A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1641902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chen, D.; Yang, M.; Liu, J. The effect of temperatures and hosts on the life cycle of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects 2022, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutyambai, D.M.; Niassy, S.; Calatayud, P.A.; Subramanian, S. Agronomic Factors Influencing Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) infestation and damage and its co-occurrence with stemborers in maize cropping systems in Kenya. Insects 2022, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, S.; Rehman, A.; Masood, M.; Ali, K.; Suleman, N. Occurrence and molecular identification of an invasive rice strain of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from Sindh, Pakistan, using mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I gene sequences. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particulars | Categories | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) | (Young) 20–30 | 50 | 24.0 |

| (Middle age) 31–50 | 110 | 52.9 | |

| (Old) 51 and above | 48 | 23.1 | |

| Qualification | (Illiterate) None | 35 | 16.8 |

| Primary to middle | 60 | 28.9 | |

| Matric and above | 113 | 54.3 | |

| Type of farming profession | Full time | 154 | 74.0 |

| Part Time | 54 | 26.0 | |

| Farming experience (yrs.) | (Beginners) 1–10 | 28 | 13.5 |

| (Skilled) 11–20 | 24 | 11.5 | |

| (Intermediate) 21–30 | 31 | 14.9 | |

| (Highly skilled) Since birth | 125 | 60.1 | |

| Landholdings (acres) | (Small) Less than 5 | 10 | 4.8 |

| (Medium) 5–12.5 acres | 49 | 23.6 | |

| (Large) 12.5–25 acres | 42 | 20.2 | |

| (Very Large) 25 and above | 107 | 51.4 | |

| Nature of holding/farm ownership | Mutual | 10 | 4.8 |

| Personal | 45 | 21.6 | |

| Lease/Rented | 44 | 21.2 | |

| Mixed | 109 | 52.4 |

| Particulars | Categories | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maize farm area (acres) | (Small) Less than 5 | 39 | 18.8 |

| (Medium) 5–12.5 | 78 | 37.5 | |

| (Large) 12.5–25 | 35 | 16.8 | |

| (Very Large) ≥ 25 | 56 | 26.9 | |

| Maize cultivation experience (yrs.) | (beginners) 1–10 | 39 | 18.8 |

| (Skilled) 11–20 | 78 | 37.5 | |

| (Intermediate) 21–30 | 35 | 16.8 | |

| (Highly skilled) Since Birth | 56 | 26.9 | |

| Purpose of maize crop | Fodder | 65 | 31.3 |

| Cash crop | 63 | 30.3 | |

| Fodder + cash crop (both) | 55 | 26.4 | |

| Silage + seed | 25 | 12.0 | |

| Selection of maize season | Spring | 25 | 12.0 |

| Autumn | 36 | 17.3 | |

| Both | 147 | 70.7 | |

| Type of maize seed | OPV | 12 | 5.8 |

| Hybrids | 115 | 55.3 | |

| Mix | 81 | 38.9 | |

| Source/procurement of maize Seed | Own seed | 6 | 2.9 |

| Trader/dealer | 173 | 83.2 | |

| Company | 6 | 2.9 | |

| Mix | 23 | 11.1 |

| Particulars | Categories | N | % | Particulars | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insect pests of maize and their identification | Maize borers | 66 | 31.7 | Contact with experts (research or extension services) | Yes | 118 | 56.7 |

| Fall armyworm | 81 | 38.9 | No | 90 | 43.3 | ||

| Shoot fly | 30 | 14.4 | Participation in farmer meetings/trainings | Yes | 109 | 52.4 | |

| Others (termites/sucking) | 31 | 14.9 | No | 99 | 47.6 | ||

| Pest management choices | Foliar spray | 52 | 25.0 | How did you hear about FAW | Yourself | 97 | 46.6 |

| Granular | 48 | 23.1 | Technical experts (extension Dep./pesticide industry rep.) | 28 | 13.5 | ||

| Both | 79 | 38.0 | Dealer/fellow farmers | 34 | 16.3 | ||

| Nothing | 29 | 13.9 | Do not know | 49 | 23.6 |

| Particulars | Categories | N | % | Particulars | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAW identification | Yes | 83 | 39.9 | Most vulnerable phase of maize plant to FAW | Vegetative | 74 | 35.6 |

| No | 125 | 60.1 | Reproductive | 44 | 21.2 | ||

| FAW damage identification | Yes | 127 | 61.1 | Both | 58 | 27.9 | |

| No | 81 | 38.9 | Do not know | 32 | 15.4 | ||

| Most damaging stage of Insect | Larvae | 150 | 72.1 | Favorite part of maize plant for FAW | Leaf | 77 | 37.0 |

| Adult | 30 | 14.4 | Others | 64 | 30.8 | ||

| Do not know | 28 | 13.5 | Do not know | 67 | 32.2 | ||

| Status of FAW | Established Pest | 58 | 27.9 | FAW larval feeding time | Day | 54 | 26 |

| Sporadic pest | 26 | 12.5 | Night | 76 | 35.6 | ||

| Minor pest | 25 | 12.0 | Do not know | 78 | 37.5 | ||

| Do not know | 99 | 47.6 | Previous year attack intensity | Do not know | 34 | 16.3 | |

| From where did it spread | India | 32 | 15.4 | No attack | 39 | 18.8 | |

| America | 32 | 15.4 | Low-intensity attack | 104 | 50.0 | ||

| Natural | 90 | 43.3 | Severe attack | 31 | 14.9 | ||

| Do not know | 54 | 26.0 | Previous year control of FAW | Controlled | 178 | 85.6 | |

| Season of FAW | Spring | 50 | 24.0 | Not controlled | 30 | 14.4 | |

| Autumn | 70 | 33.7 | Future threat/fate of FAW | Do not know | 86 | 41.3 | |

| Both | 44 | 21.2 | Threat to maize crops | 73 | 35.1 | ||

| Do not know | 44 | 21.2 | Threat to other crops | 26 | 12.5 | ||

| No threat | 23 | 11.1 |

| Predictors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Age | Education | Type of Farming | Farming Experience | |

| Can you recognize different pests of maize? | |||||

| Fall armyworm | −0.042 (0.269) | 0.105 (0.243) | 1.08 (0.567) | 0.059 (0.16) | |

| Shoot fly | 0.319 (0.374) | −0.059 (0.330) | 1.538 (0.699) * | −0.058 (0.788) | |

| Others (termites/sucking) | 0.100 (0.369) | −0.121 (0.328) | 1.71 (0.656) ** | 0.094 (0.219) | |

| Maize borers | Reference category | ||||

| From where did you first hear about FAW? | |||||

| Technical experts | −0.188 (0.357) | 0.031 (0.32) | −1.512 (0.837) | −0.523 (0.204) ** | |

| Dealer/fellow farmers | −0.038 (0.319) | −0.162 (0.284) | −2.184 (1.069) * | −0.109 (0.204) | |

| Do not know | −0.105 (0.321) | 0.063 (0.287) | 0.777 (0.475) | −0.188 (0.191) | |

| Self-observation | Reference category | ||||

| FAW’s status as pest perceived by the farmer? | |||||

| Established pest | −0.042 (0.289) | 0.001 (0.263) | −0.833 (0.484) | −0.191 (0.171) | |

| Sporadic pest | −0.294 (0.376) | 0.174 (0.339) | −18.016 (0.000) *** | −0.100 (0.223) | |

| Minor pest | 0.409 (0.392) | 0.808 (0.383) * | −2.903 (1.116) ** | −0.086 (0.237) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| From where did FAW spread to Pakistan? | |||||

| India | 0.048 (0.361) | −0.129 (0.313) | −0.507 (0.659) | −0.062 (0.221) | |

| America | 0.356 (0.367) | 0.273 (0.324) | −0.613 (0.606) | −0.297 (0.209) | |

| Natural | 0.071 (0.278) | 0.383 (0.251) | −0.573 (0.206) | 0.035 (0.166) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| In which season has the severity of FAW been observed? | |||||

| Spring | 0.204 (0.335) | −0.041 (0.310) | −1.224 (0.615) * | 0.188 (0.205) | |

| Autumn | −0.151 (0.328) | 0.299 (0.294) | −0.464 (0.497) | 0.292 (0.186) | |

| Both | −0.222 (0.370) | 0.047 (0.326) | −0.962 (0.626) | 0.160 (0.212) | |

| Do not Know | Reference category | ||||

| Do you know about the most damaging stage of FAW? | |||||

| Larvae | 0.420 (0.312) | 0.042 (0.268) | −0.596 (0.487) | −0.110 (0.180) | |

| Adult | 0.177 (0.349) | 0.536 (0.315) | −0.892 (0.566) | −0.067 (0.202) | |

| Do not Know | Reference category | ||||

| Farmers’ perception about the most vulnerable crop phase to larvae of FAW? | |||||

| Reproductive | 0.422 (0.321) | 0.599 (0.293) * | −0.490 (0.582) | −0.189 (0.191) | |

| Both | −0.011 (0.458) | −0.085 (0.375) | −0.500 (0.877) | −0.476 (0.255) | |

| Do not Know | 0.451 (0.276) | 0.526 (0.249) * | 0.131 (0.454) | −0.111 (0.163) | |

| Vegetative | Reference category | ||||

| Can you talk about the most preferred part of the maize plant for FAW larvae ? | |||||

| Leaf | 0.037 (0.277) | −0.562 (1.038) * | −0.169 (0.500) | 0.149 (0.162) | |

| Other parts | 0.322 (0.310) | −0.889 (0.288) ** | 0.691 (0.521) | 0.105 (0.191) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Do you have any idea about the preferred feeding time of FAW larvae? | |||||

| Nighttime | −0.141 (0.318) | 0.351 (0.869) | 0.056 (0.526) | −0.228 (0.188) | |

| Do not know | −0.178 (0.317) | 0.113 (0.284) | −0.446 (0.568) | −0.031 (0.196) | |

| Daytime | Reference category | ||||

| What type of chemical formulation do you prefer to manage FAW? | |||||

| Spray | 0.378 (0.337) | 0.257 (1.460) | −0.110 (0.656) | −0.342 (0.194) | |

| Granular | −0.166 (0.321) | −0.119 (0.286) | 1.067 (0.545) * | 0.169 (0.186) | |

| Both | 0.555 (0.359) | 0.068 (0.326) | 1.153 (0.550) * | −0.370 (0.207) | |

| Nothing | Reference category | ||||

| Do you have any information about the intensity of FAW in maize crop last year? | |||||

| Do not Know | −0.010 (0.900) | −0.077 (0.990) | −0.178 (0.566) | −0.224 (0.186) | |

| No attack | 0.959 (0.366) ** | −0.010 (0.317) | −0.660 (0.615) | 0.089 (0.233) | |

| Severe attack | 0.662 (0.345) * | −0.168 (0.639) | −0.590 (0.639) | −0.385 (0.205) | |

| Low-intensity attack | Reference category | ||||

| What was the perception of farmers about FAW as a future threat? | |||||

| Do not know | −0.267 (0.437) | −0.467 (0.437) | −0.582 (0.661) | −0.803 (0.402) * | |

| Threat to maize crops | −0.245 (0.452) | −0.043 (0.454) | −0.667 (0.689) | −1.085 (0.406) ** | |

| Threat to other crops | 0.061 (0.533) | −0.109 (0.516) | −2.051 (1.001) * | −1.281 (0.003) ** | |

| No threat at all | Reference category | ||||

| Variables | Predictors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Landholding | Nature of Land Possession | Maize Crop Area | Maize Farming Experience | ||

| Can you recognize different pests of maize? | |||||

| Fall armyworm | 0.280 (0.294) | 0.124 (0.188) | −0.135 (0.335) | 0.103 (0.285) | |

| Shoot fly | −0.264 (0.419) | 0.154 (0.275) | −0.299 (0.453) | 0.597 (0.347) | |

| Others (termites/sucking) | −0.277 (0.417) | 0.169 (0.294) | −0.466 (0.433) | 0.665 (0.331) * | |

| Maize borers | Reference category | ||||

| From where did you first hear about FAW? | |||||

| Technical experts | −0.565 (0.393) | 0.359 (0.272) | 0.148 (0.446) | 0.035 (0.396) | |

| Dealer/fellow farmers | −0.486 (0.369) | 0.428 (0.251) | −0.067 (0.396) | 0.143 (0.335) | |

| Do not know | −1.187 (0.393) ** | 0.099 (0.238) | 0.190 (0.421) | 0.440 (0.306) | |

| Self-observation | Reference category | ||||

| FAW’s status as pest perceived by the farmer? | |||||

| Established pest | 0.197 (0.328) | −0.412 (0.211) * | 0.933 (0.386) * | −0.410 (0.312) | |

| Sporadic pest | 0.087 (0.417) | −0.390 (0.274) | 1.119 (0.496) * | −0.483 (0.425) | |

| Minor pest | −0.322 (0.406) | −0.119 (0.288) | 0.653 (0.505) | −0.359 (0.427) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| From where did FAW spread to Pakistan? | |||||

| India | 0.343 (0.406) | −0.257 (0.258) | 0.024 (0.435) | 0.092 (0.348) | |

| America | 0.015 (0.415) | 0.095 (0.268) | 0.201 (0.444) | 0.129 (0.355) | |

| Natural | 0.277 (0.310) | −0.094 (0.215) | −0.153 (0.335) | 0.232 (0.257) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| In which season has the severity of FAW been observed? | |||||

| Spring | 0.447 (0.376) | −0.037 (0.256) | 0.340 (0.412) | −0.084 (0.323) | |

| Autumn | −0.140 (0.354) | 0.363 (0.261) | 0.371 (0.383) | −0.220 (0.280) | |

| Both | 0.251 (0.401) | 0.040 (0.269) | 0.777 (0.454) | −0.502 (0.346) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Do you know about the most damaging stage of FAW? | |||||

| Larvae | −0.219 (0.314) | 0.318 (0.224) | 0.349 (0.367) | −0.239 (0.275) | |

| Adult | 0.160 (0.373) | −0.009 (0.241) | 0.068 (0.411) | −0.042 (0.318) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Farmers’ perception about the most vulnerable crop phase to larvae of FAW? | |||||

| Reproductive | −0.468 (0.360) | −0.013 (0.277) | 0.471 (0.401) | −0.233 (0.330) | |

| Both | 0.007 (0.466) | −0.151 (0.316) | −0.074 (0.543) | −0.054 (0.461) | |

| Do not know | −0.215 (0.303) | 0.011 (0.199) | −0.237 (0.332) | 0.383 (0.268) | |

| Vegetative | Reference category | ||||

| Can you talk about the most preferred part of the maize plant for FAW larvae ? | |||||

| Leaf | 0.146 (0.306) | −0.103 (0.193) | −0.745 (0.365) * | 0.221 (0.316) | |

| Other parts | −0.390 (0.357) | 0.110 (0.223) | −0.676 (0.408) | 0.462 (0.337) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Do you have any idea about the preferred feeding time of FAW larvae? | |||||

| Nighttime | 0.243 (0.350) | −0.152 (0.252) | 0.825 (0.402) * | −0.765 (0.320) * | |

| Do not know | 0.563 (0.357) | −0.273 (0.250) | 1.61 (0.440) ** | −1.148 (0.371) ** | |

| Daytime | Reference category | ||||

| What type of chemical formulation did you prefer to manage FAW? | |||||

| Spray | −0.009 (0.306) | −0.284 (0.235) | 0.364 (0.412) | −0.157 (0.335) | |

| Granular | 0.454 (0.338) | 0.105 (0.248) | −0.288 (0.397) | −0.463 (0.334) | |

| Both | 0.658 (0.409) | 0.188 (0.242) | 0.003 (0.433) | −0.320 (0.374) | |

| Nothing | Reference category | ||||

| Did you have any information about intensity of FAW in maize crop last year? | |||||

| Do not know | −0.367 (0.343) | 0.098 (0.251) | 0.333 (0.428) | −0.417 (0.361) | |

| No attack | −0.123 (0.398) | 0.070 (0.250) | −0.338 (0.427) | 0.552 (0.326) | |

| Severe attack | −0.446 (0.426) | 0.086 (0.226) | 1.167 (0.457) ** | −0.466 (0.377) | |

| Low intensity | Reference category | ||||

| What was the perception of farmers about FAW as a future threat? | |||||

| Do not know | 0.297 (0.545) | 0.106 (0.362) | 0.143 (0.567) | −0.711 (0.61) | |

| Threat to maize crop | 0.504 (0.562) | −0.090 (0.359) | 0.585 (0.595) | −0.814 (0.418) * | |

| Threat to other crops | 1.036 (0.653) | −0.007 (0.400) | 0.471 (0.675) | −0.768 (0.517) | |

| No threat at all | Reference category | ||||

| Variables | Predictors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose of Maize Crop | Selection of Maize Season | Type of Maize Seed | Source of Maize Seed | ||

| Can you recognize different pests of maize? | |||||

| Fall armyworm | 0.329 (0.191) | 0.001 (0.270) | 0.242 (0.321) | -0.321 (0.326) | |

| Shoot fly | 0.347 (0.256) | −0.721 (0.334) * | 0.926 (0.422) *** | 0.302 (0.374) | |

| Others (termites/sucking) | 0.050 (0.255) | −0.686 (0.333) * | 0.205 (0.480) | 0.401 (0.340) | |

| Maize borers | Reference category | ||||

| From where did you first hear about FAW? | |||||

| Technical experts | −0.397 (0.276) | −0.278 (0.348) | -0.050 (0.433) | −0.068 (0.547) | |

| Dealer/fellow farmers | −0.204 (0.230) | 0.556 (0.366) | -0.029 (0.374) | 0.238 (0.381) | |

| Do not know | 0.107 (0.217) | 0.028 (0.303) | -0,091 (0.359) | 0.725 (0.309) ** | |

| Self-observation | Reference category | ||||

| FAW’s status as pest perceived by the farmer? | |||||

| Established pest | −0.417 (0.201) * | 0.641 (0.305) * | 0.433 (0.335) | −0.555 (0.320) | |

| Sporadic pest | −0.026 (0.276) | 0.059 (0.321) | 0.637 (0.466) | −0.981 (0.727) | |

| Minor pest | −0.538 (0.273) | 0.039 (0.343) | 0.827 (0.450) | −1.251 (0.616) * | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| From where did FAW spread to Pakistan? | |||||

| India | 0.209 (0.247) | −0.105 (0.342) | 0.607 (0.435) | −1.486 (0.705) * | |

| America | 0.011 (0.254) | 0.153 (0.366) | 0.348 (0.417) | −0.771 (0.467) | |

| Natural | −0.074 (0.191) | −0.187 (0.266) | 0.106 (0.308) | −0.025 (0.257) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| In which season has the severity of FAW severity been observed? | |||||

| Spring | 0.047 (0.239) | 0.550 (0.308) | 0.035 (0.395) | −0.710 (0.377) | |

| Autumn | 0.016 (0.221) | 0.597 (0.290) * | 0.138 (0.348) | −0.262 (0.284) | |

| Both | 0.016 (0.254) | 1.002 (0.355) ** | −0.160 (0.423) | −1.006 (0.446) * | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Do you know about the most damaging stage of FAW? | |||||

| Larvae | −0.092 (0.206) | 0.206 (0.306) | −0.177 (0.342) | 0.192 (0.305) | |

| Adult | −0.028 (0.234) | −0.233 (0.334) | −0.473 (0.388) | −0125 (0.358) | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Farmers’ perception about the most vulnerable crop phase to larvae of FAW? | |||||

| Reproductive | −0.248 (0.221) | −0.139 (0.314) | −0.477 (0.382) | −0.544 (0.419) | |

| Both | −0.027 (0.327) | −0.072 (0.421) | −0.278 (0.544) | −0.010 (0.560) | |

| Do not know | 0.248 (0.188) | −0.576 (0.264) * | 0.037 (0.314) | 0.403 (0.284) | |

| Vegetative | Reference category | ||||

| Do you have any idea about the preferred part of maize plant by larvae of FAW? | |||||

| Leaf | −0.056 (0.204) | 0.383 (0.259) | 0.502 (0.339) | 0.855 (0.435) * | |

| Other parts | 0.624 (0.223) ** | 0.086 (0.287) | 0.383 (0.373) | 1.056 (0.434) ** | |

| Do not know | Reference category | ||||

| Do you have an idea about the preferred feeding time of FAW larvae? | |||||

| Nighttime | −0.066 (0.217) | −0.121 (0.296) | −0.199 (0.361) | −1.109 (0.356) ** | |

| Do not know | −0.075 (0.218) | 0.223 (0.312) | −0.558 (0.371) | −0.900 (0.332) ** | |

| Daytime | Reference category | ||||

| What type of chemical formulation do you prefer to manage FAW? | |||||

| Spray | −0.186 (0.233) | −0.575 (0.304) | −0.351 (0.399) | −0.325 (0.383) | |

| Granular | −0.350 (0.226) | −0.820 (0.290) ** | −0.063 (0.380) | 0.020 (0.349) | |

| Both | −0.272 (0.242) | −0.551 (0.337) | −0.325 (0.418) | −0.687 (0.517) | |

| Nothing | Reference category | ||||

| Do you have any information about the intensity of FAW in maize crop last year? | |||||

| Do not know | 0.129 (0.233) | −0.521 (0.273) * | −0.722 (0.403) | −0.225 (0.432) | |

| No attack | 0.439 (0.235) | 0.344 (0.435) | −0.342 (0.384) | 0.930 (0.302) ** | |

| Severe attack | 0.512 (0.240) * | −0.295 (0.314) | −0.245 (0.429) | −0.243 (0.525) | |

| Low-intensity attack | Reference category | ||||

| What was the perception of farmers about FAW as a future threat? | |||||

| Do not know | 0.113 (0.290) | 0.069 (0.443) | 0.254 (0.428) | −0.689 (0.317) * | |

| Threat to maize crop | 0.295 (0.301) | 0.283 (0.456) | 0.142 (0.457) | −1.025 (0.378) ** | |

| Threat to other crops | −0.139 (0.368) | 0.397 (0.535) | 0.548 (0.580) | −1.005 (0.656) | |

| No threat at all | Reference category | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akbar, W.; Yousaf, S.; Saeed, M.F.; Alkherb, W.A.H.; Abbasi, A.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Suleman, N. Farmers’ Perception of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) as an Invasive Pest and Its Management. Insects 2025, 16, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16040427

Akbar W, Yousaf S, Saeed MF, Alkherb WAH, Abbasi A, Rebouh NY, Suleman N. Farmers’ Perception of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) as an Invasive Pest and Its Management. Insects. 2025; 16(4):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16040427

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkbar, Waseem, Sumaira Yousaf, Muhammad Farhan Saeed, Wafa A. H. Alkherb, Asim Abbasi, Nazih Y. Rebouh, and Nazia Suleman. 2025. "Farmers’ Perception of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) as an Invasive Pest and Its Management" Insects 16, no. 4: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16040427

APA StyleAkbar, W., Yousaf, S., Saeed, M. F., Alkherb, W. A. H., Abbasi, A., Rebouh, N. Y., & Suleman, N. (2025). Farmers’ Perception of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) as an Invasive Pest and Its Management. Insects, 16(4), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16040427