Essential Oils and Bioproducts for Flea Control: A Critical Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Fleas

1.1.1. Biology and Ecology

1.1.2. Medical and Veterinary Importance

1.1.3. Control Strategies and Challenges

1.2. Essential Oils and Bioactive Compounds

2. Methods

2.1. Article Search Strategy

2.2. Article Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis Criteria

3. Results

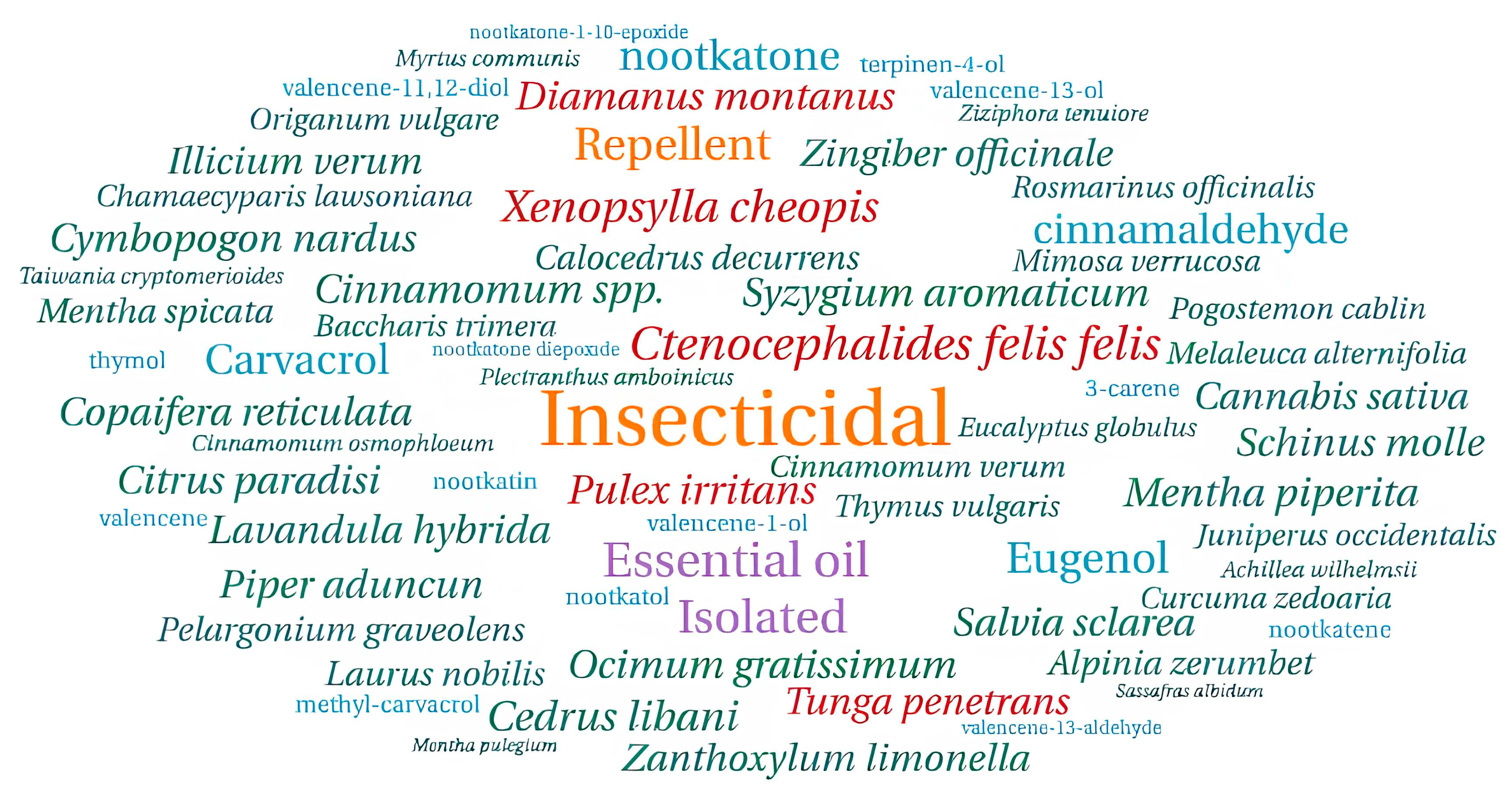

3.1. General Results

3.2. Insecticidal Activity of Essential Oils

3.2.1. Immature Stages

3.2.2. Adult Stages

3.2.3. Overview of Insecticidal Activity of Essential Oil-Based Formulations

| Essential Oil | LC50 (µg·mL−1) | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Species | Botanical Family | Eggs | Larvae | Pupae | Adults | Growth-Disrupting Activity | |

| Alpinia zerumbet | Zingiberaceae | 653.5 | 364.5 | Not available | 27,665.5 | Not available | [113] |

| Baccharis trimera | Asteraceae | 15,647.2 | 1747.1 | 16,385.8 | 16,206.5 | Not available | [124] |

| Cannabis sativa | Cannabaceae | 1640.5 | 4631.2 | 23,578.5 | 46,396.0 | Not available | [125] |

| Cinnamomum spp. | Lauraceae | 90 | 21.5 | Not available | 2093.5 | Not available | [113] |

| Cinnamomum cassia | Lauraceae | 150 | 860.0 | 1730.0 | 3735.0 | 115.0 | [126] |

| Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | No biological activity | No biological activity | No biological activity | No biological activity | No biological activity | [127] |

| Copaifera reticulata | Fabaceae | No biological activity | 11,530.0 | 11,155.0 | 23,125.0 | 5000.0 | [127] |

| Curcuma zedoaria | Zingiberaceae | 2482.5 | 3873.0 | 5154.0 | 12,775.5 | Not available | [128] |

| Cymbopogon nardus | Poaceae | 599.0 | 366.0 | Not available | 4492.79–29,852.5 | Not available | [113] |

| Illicium verum | Schisandraceae | 1845.0 | 720.0 | 1770.0 | 6085.0 | 395.0 | [129] |

| Laurus nobilis | Lauraceae | 120.5 | 26.0 | Not available | 20,604.5 | Not available | [113] |

| Lavandula hybrida | Lamiaceae | 8570.0 | 7100.0 | 33,645.0 | 27,965.0 | 2390.0 | [127] |

| Mentha piperita | Lamiaceae | Not available | Not available | Not available | 8470.8 | Not available | [130] |

| Mentha spicata | Lamiaceae | 1519.5 | 628.5 | Not available | 29,878.0 | Not available | [113] |

| Mimosa verrucosa | Fabaceae | 9725.0 | 13,312.5 | No biological activity | 18,461.0 | Not available | [131] |

| Ocimum gratissimum | Lamiaceae | 89.5–527.22 | 60.28–1053.44 | 934.9 | 292.50–1012.00 | 100.0 | [113] |

| Origanum vulgare | Lamiaceae | 4740.0 | 7755.0 | 4920.0 | 1675.0 | 310.0 | [126] |

| Pelargonium graveolens | Geraniaceae | 940.0 | 1005.0 | 3380.0 | 8650.0 | 625.0 | [129] |

| Piper aduncum | Piperaceae | Not available | Not available | Not available | 336.0–547.0 | 25–30 | [132] |

| Pogostemon cablin | Lamiaceae | 2460.0 | 3135.0 | 2305.0 | 3030.0 | Not available | [133] |

| Salvia sclarea | Lamiaceae | 19,510.0 | 5185.0 | 23,750.0 | 44,550.0 | 3750.0 | [127] |

| Schinus molle (leaves and fruits) | Anacardiaceae | No biological activity | Not available | Not available | 601.0 and 17,697.5 | Not available | [107] |

| Syzygium aromaticum | Myrtaceae | Not available | Not available | Not available | 285.0–829.3 | 15.0 | [130,134] |

| Thymus vulgaris | Lamiaceae | 675.0 | 1770.0 | 10,160.0 | 3225.0 | 235.0 | [126] |

| Zanthoxylum limonella | Rutaceae | Not available | Not available | Not available | 9632.0 | Not available | [130] |

| Zingiber officinale | Zingiberaceae | Not available | Not available | Not available | 11,907.2 | Not available | [130] |

| Essential Oil | LC50 (µg·mL−1) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Species | Botanical Family | ||

| Calocedrus decurrens | Cupressaceae | 3.4 | [135] |

| Chamaecyparis lawsoniana | Cupressaceae | 6.1 | [135] |

| Cinnamomum spp. | Lauraceae | 24.0 | [122] |

| Cinnamomum verum | Lauraceae | 0.3 | [136] |

| Eucalyptus globulus | Myrtaceae | 23,700 | [137] |

| Juniperus occidentalis | Cupressaceae | 11.6 | [135] |

| Mentha piperita | Lamiaceae | 18,000 | [137] |

| Salvia rosmarinus | Lamiaceae | 3.7 | [136] |

| Syzygium aromaticum | Myrtaceae | 36.3 | [122] |

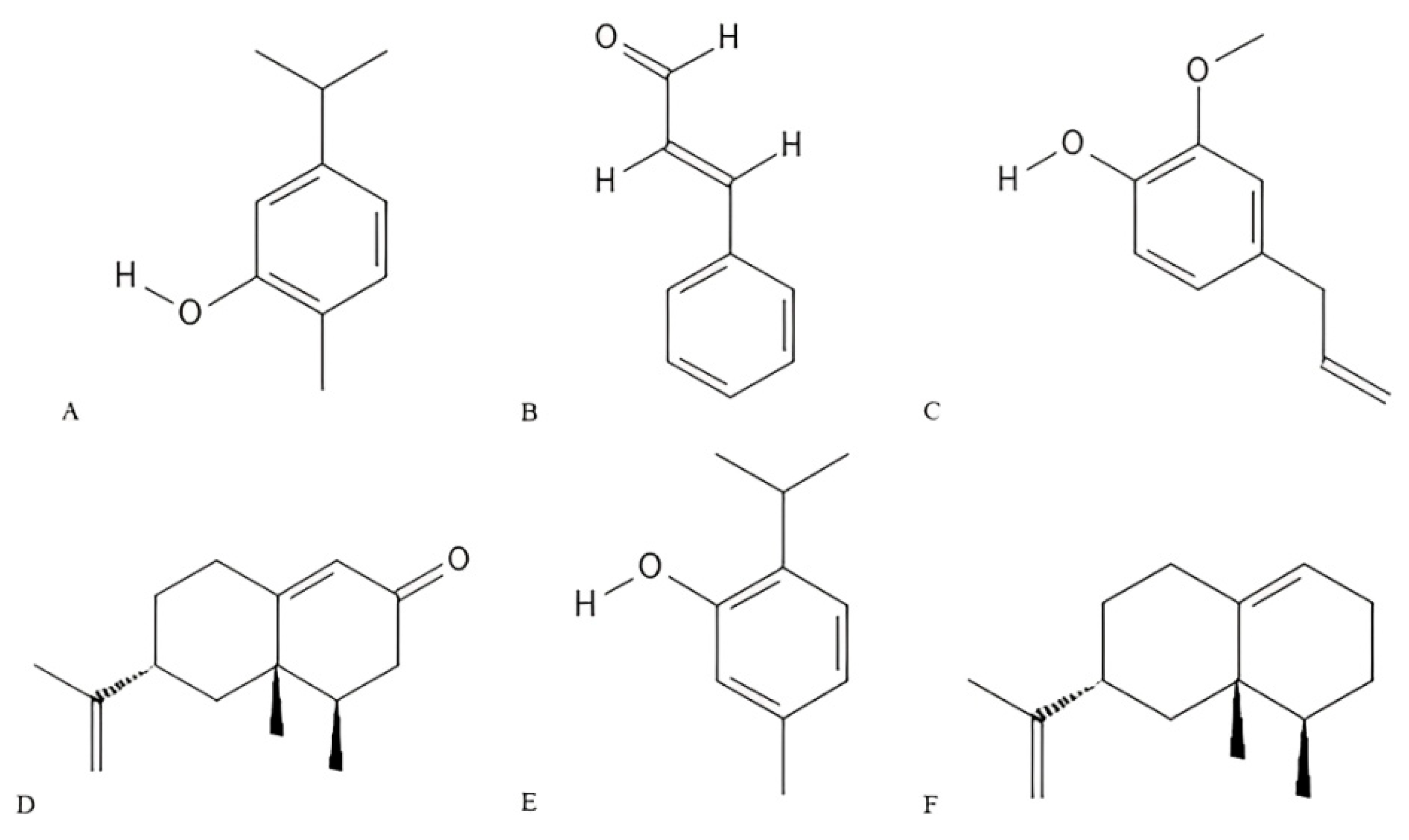

3.3. Insecticidal Activity of Bioactive Compounds

Overview of Insecticidal Activity in Bioactive-Based Formulations

| Flea Species | Bioactive Compounds | Chemical Class | Evolutive Forms | LC50 (µg·mL−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctenocephalides felis | Eugenol | Phenylpropanoid | Eggs | 48.9 | [138] |

| Larvae | 491.8 | [138] | |||

| Pupae | 58.6 | [138] | |||

| Adults | 120.0–259.0 | [134,138] | |||

| Eggs–Adults | 5–6.83 | [113,138] | |||

| Dillapiole | Phenylpropanoid | Eggs–Adults | 25.2–30.3 | [132] | |

| Adults | 336.0–547.0 | [132] | |||

| Cinnamaldehyde | Phenylpropanoid | Eggs–Adults | 8.8 | [124] | |

| Xenopsylla cheopis | Carvacrol | Monoterpene | Adults | 59.0 | [140] |

| 3-Carene | No biological activity | ||||

| Terpine-4-ol | No biological activity | ||||

| Methyl-carvacrol | No biological activity | ||||

| Nootkatone | Sesquiterpene | Adults | 29–83 | [140] | |

| Valencene-13-ol | 83.0 | ||||

| Valencene-13-aldehyde | 85.0 | ||||

| Nootkatene | 170.0 | ||||

| Nootkatone 1–10 epoxide | 170.0 | ||||

| Nootkatol | 240 | ||||

| Valencene | 410.0 | ||||

| Nootkatone--diepoxide | 640.0 | ||||

| Nootkatin | No biological activity | ||||

| Valencene-11,12-diol | No biological activity |

3.4. Repellent Activity of Essential Oils and Bioactive Compounds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bossard, R.L.; Lareschi, M.; Urdapilleta, M.; Cutillas, C.; Zurita, A. Flea (Insecta: Siphonaptera) Family Diversity. Diversity 2023, 15, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardi, P.M. Fleas as Useful Tools for Science. Diversity 2023, 15, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesenato, I.P.; de Oliveira Jorge Costa, J.; de Castro Jacinavicius, F.; Bassini-Silva, R.; Soares, H.S.; Fakelmann, T.; Castelli, G.N.; Maia, G.B.; Onofrio, V.C.; Nieri-Bastos, F.A.; et al. Brazilian Fleas (Hexapoda: Siphonaptera): Diversity, Host Associations, and New Records on Small Mammals from the Atlantic Rainforest, Including Rickettsia Screening. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, A.L.; Webb, C.E.; Clark, N.J.; Halajian, A.; Mihalca, A.D.; Miret, J.; D’Amico, G.; Brown, G.; Kumsa, B.; Modrý, D.; et al. Out-of-Africa, Human-Mediated Dispersal of the Common Cat Flea, Ctenocephalides felis: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to World Domination. Int. J. Parasitol. 2019, 49, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobler, G.; Pfeffer, M. Fleas as Parasites of the Family Canidae. Parasite Vectors 2011, 4, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crkvencic, N.; Šlapeta, J. Climate Change Models Predict Southerly Shift of the Cat Flea (Ctenocephalides felis) Distribution in Australia. Parasite Vectors 2019, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, S.; Gillespie, T.R.; Miarinjara, A. Xenopsylla cheopis (Rat Flea). Trends Parasitol. 2022, 38, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, C.D.; Beerntsen, B.T.; Song, Q.; Anderson, D.M. Transovarial Transmission of Yersinia Pestis in Its Flea Vector Xenopsylla cheopis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarm, A.; Dalimi, A.; Pirestani, M.; Mohammadiha, A.; Zahraei-Ramazani, A.; Marvi-Moghaddam, N.; Amiri, E. Pulex irritans on Dogs and Cats: Morphological and Molecular Approach. J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2022, 16, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miarinjara, A.; Bland, D.M.; Belthoff, J.R.; Hinnebusch, B.J. Poor Vector Competence of the Human Flea, Pulex Irritans, to Transmit Yersinia Pestis. Parasite Vectors 2021, 14, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, A.; Callejón, R.; García-sánchez, Á.M.; Urdapilleta, M.; Lareschi, M.; Cutillas, C. Origin, Evolution, Phylogeny and Taxonomy of Pulex irritans. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2019, 33, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannino, F.; Sulli, N.; Maitino, A.; Pascucci, I.; Pampiglione, G.; Salucci, S. Pulci Di Cane e Gatto: Specie, Biologia e Malattie Ad Esse Associate. Vet. Ital. 2017, 53, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Micheal, W. Dryden Biology of Fleas of Dog and Cats. Compend. Contin. Educ. Pract. Vet. 1993, 15, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, N.J. The Homology of Mouthparts in Fleas (Insecta, Aphaniptera). Entomol. Rev. 2002, 82, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, M.H.; Hsu, Y.C.; Wu, W.J. Consumption of Flea Faeces and Eggs by Larvae of the Cat Flea, Ctenocephalides felis. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2002, 16, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.H.; Wu, W.J. Off-Host Observations of Mating and Postmating Behaviors in the Cat Flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2001, 38, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossard, R.L.; Broce, A.B.; Dryden, M.W. Effects of Circadian Rhythms and Other Bioassay Factors on Cat Flea. J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 2000, 73, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, M.K.; Dryden, M.W. The Biology, Ecology, and Management of the Cat Flea. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1997, 42, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, N.C.; Koehler, P.G.; Patterson, R.S. Egg Production, Larval Development, and Adult Longevity of Cat Fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) Exposed to Ultrasound. J. Econ. Entomol. 1990, 83, 2306–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.H. Distribution of Cat Flea Larvae in the Carpeted Household Environment. Vet. Dermatol. 1995, 6, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiondo, A.A.; Meola, S.M.; Palma, K.G.; Slusser, J.H.; Meola, R.W. Chorion Formation and Ultrastructure of the Egg of the Cat Flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1999, 36, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden, L.A.; Hinkle, N.C. Fleas (Siphonaptera). In Medical and Veterinary Entomology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, W.; Foil, L.D. The Effects of Diet upon Pupal Development and Cocoon Formation by the Cat Flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Vector Ecol. 2002, 27, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden, M.W.; Reid, B.L. Insecticide Susceptibility of Cat Flea (Siphonaptera: Publicidae) Pupae. J. Econ. Entomol. 1996, 89, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azrizal-Wahid, N.; Sofian-Azirun, M.; Low, V.L. New Insights into the Haplotype Diversity of the Cosmopolitan Cat Flea Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 281, 109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardi, P.M.; Santos, J.L.C. Ctenocephalides felis felis vs. Ctenocephalides canis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae): Some Issues in Correctly Identify These Species. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2012, 21, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.K. Recent Advancements in the Control of Cat Fleas. Insects 2020, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Mescht, L.; Matthee, S.; Matthee, C.A. New Taxonomic and Evolutionary Insights Relevant to the Cat Flea, Ctenocephalides felis: A Geographic Perspective. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 155, 106990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, A.; Callejón, R.; De Rojas, M.; Halajian, A.; Cutillas, C. Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis: Introgressive Hybridization? Syst. Entomol. 2016, 41, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, C.L.; Martin, E.; Brendel, L. Human Flea Pulex irritans Linnaeus, 1758 (Insecta: Siphonaptera: Pulicidae): EENY-798 IN1383, 11 2022. EDIS 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, S.; Clark, F.; Greenwood, M.; Larsen, K.S. Host Location, Survival and Fecundity of the Oriental Rat Flea Xenopsylla cheopis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) in Relation to Black Rat Rattus rattus (Rodentia: Muridae) Host Age and Sex. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2002, 92, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N.; Abari, E.; D’hAese, J.; Calheiros, C.; Heukelbach, J.; Mencke, N.; Feldmeier, H.; Mehlhorn, H. Investigations on the Life Cycle and Morphology of Tunga penetrans in Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 101, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampiglione, S.; Fioravanti, M.L.; Gustinelli, A.; Onore, G.; Mantovani, B.; Luchetti, A.; Trentini, M. Sand Flea (Tunga spp.) Infections in Humans and Domestic Animals: State of the Art. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2009, 23, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng-Nguyen, D.; Hii, S.-F.; Hoang, M.-T.T.; Nguyen, V.-A.T.; Rees, R.; Stenos, J.; Traub, R.J. Domestic Dogs Are Mammalian Reservoirs for the Emerging Zoonosis Flea-Borne Spotted Fever, Caused by Rickettsia felis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, D.; Craig, M.; Crittall, J.; Elsheikha, H.; Griffiths, K.; Keyte, S.; Merritt, B.; Richardson, E.; Stokes, L.; Whitfield, V.; et al. Fleas and Flea-Borne Diseases: Biology, Control & Compliance. Companion Anim. 2018, 23, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardi, P.M. Fleas and Diseases. In Arthropod Borne Diseases; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 517–536. [Google Scholar]

- Eads, D.A.; Hoogland, J.L. Precipitation, Climate Change, and Parasitism of Prairie Dogs by Fleas that Transmit Plague. J. Parasitol. 2017, 103, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, A. Climate Change and Its Potential for Altering the Phenology and Ecology of Some Common and Widespread Arthropod Parasites in New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 2021, 69, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritani, K. Different Effects of Climate Change on the Population Dynamics of Insects. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2013, 48, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.K. The Biology and Ecology of Cat Fleas and Advancements in their Peste Management—A Review. Insects 2017, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, S.; McGarry, J.; Noble, P.M.; Pinchbeck, G.J.; Cantwell, S.; Radford, A.D.; Singleton, D.A. Seasonality and Other Risk Factors for Fleas Infestations in Domestic Dogs and Cats. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2023, 37, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, C.F. Pruritus in Dogs and Cats Part 2: Allergic Causes of Pruritus and the Allergic Patient. Vet. Nurse 2022, 13, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Simpson, A.; Bloom, P.; Diesel, A.; Friedeck, A.; Paterson, T.; Wisecup, M.; Yu, C.M. 2023 AAHA Management of Allergic Skin Diseases in Dogs and Cats Guidelines. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2023, 59, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, D.; Pucheu-Haston, C.M.; Prost, C.; Mueller, R.S.; Jackson, H. Clinical Signs and Diagnosis of Feline Atopic Syndrome: Detailed Guidelines for a Correct Diagnosis. Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 32, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, R.J.; Gage, K.L. Transmission of Flea-Borne Zoonotic Agents. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012, 57, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.O.; André, M.R.; Šlapeta, J.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Vector Biology of the Cat Flea Ctenocephalides felis. Trends Parasitol. 2024, 40, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.; Castro, A.; Novo, T.; Maia, C. Dipylidium caninum in the Twenty-First Century: Epidemiological Studies and Reported Cases in Companion Animals and Humans. Parasite Vectors 2022, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brianti, E.; Gaglio, G.; Napoli, E.; Giannetto, S.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Bain, O.; Otranto, D. New Insights into the Ecology and Biology of Acanthocheilonema reconditum (Grassi, 1889) Causing Canine Subcutaneous Filariosis. Parasitology 2012, 139, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, E.; Brianti, E.; Falsone, L.; Gaglio, G.; Foit, S.; Abramo, F.; Annoscia, G.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Giannetto, S.; Otranto, D. Development of Acanthocheilonema reconditum (Spirurida, Onchocercidae) in the Cat Flea Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera, Pulicidae). Parasitology 2014, 141, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, A.; Werkmeister, E.; Sebbane, F.; Bontemps-Gallo, S. Protocol for Monitoring Yersinia Pestis Colonization of the Proventriculus in the Flea Xenopsylla cheopis Using Microscopy. STAR Protoc. 2025, 6, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellgrove, A.N.; Goddard, J. Murine Typhus: A Re-Emerging Rickettsial Zoonotic Disease. J. Vector Ecol. 2024, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, L.S. Murine Typhus: A Review of a Reemerging Flea-Borne Rickettsiosis with Potential for Neurologic Manifestations and Sequalae. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2023, 15, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareschi, M.; Venzal, J.M.; Nava, S.; Mangold, A.J.; Portillo, A.; Palomar-Urbina, A.M.; Oteo-Revuelta, J.A. The Human Flea Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) in Northwestern Argentina, with an Investigation of Bartonella and Rickettsia spp. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2018, 89, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutebi, F.; Krücken, J.; Feldmeier, H.; von Samsom-Himmelstjerna, G. Clinical Implications and Treatment Options of Tungiasis in Domestic Animals. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 4113–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrha, S.; Heukelbach, J.; Peterson, G.M.; Christenson, J.K.; Carroll, S.; Kosari, S.; Bartholomeus, A.; Feldmeier, H.; Thomas, J. Clinical Interventions for Tungiasis (Sand Flea Disease): A Systematic Review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e234–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cárdenas, C.D.; Moreno-Leiva, C.; Vega-Memije, M.E.; Juarez-Duran, E.R.; Arenas, R. Tungiasis. In Skin Disease in Travelers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, M. Insecticide Resistance in Fleas. Insects 2016, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gazzar, L.M.; Patterson, R.S.; Koehler, P.G. Comparisons of Cat Flea (Sphonaptera: Pulicidae) Adult and Larval Insecticide Susceptibility. Fla. Entomol. 1988, 71, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.K.; Boone, J.S.; Moran, J.E.; Tyler, J.W.; Chambers, J.E. Assessing Intermittent Pesticide Exposure from Flea Control Collars Containing the Organophosphorus Insecticide Tetrachlorvinphos. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2008, 18, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, P.G.; Moye, A.H. Chlorpyrifos Formulation Effect on Airborne Residues Following Broadcast Application for Cat Flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) Control. J. Econ. Entomol. 1995, 88, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.M. Flea Control: An Overview of Treatment Concepts for North America. Vet. Dermatol. 1995, 6, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E.; Buker, F.N.; Colbunr, E.L. Insecticidal Activity of Propoxur and Carbaryl Impregnated Flea Collars Against Ctenocephalifes felis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1977, 38, 923–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.K.; Reierson, D.A. Activity of Insecticides Against the Preemerged Adult Cat Flea in the Cocoon (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1989, 26, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, P.G. Organophosphate and Carbamate Poisoning. Arch. Intern. Med. 1994, 154, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.M.; Aaron, C.K. Organophosphate and Carbamate Poisoning. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 33, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadón, A.; Arés, I.; Martínez, M.A.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R. Pyrethrins and Synthetic Pyrethroids: Use in Veterinary Medicine. In Natural Products; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 4061–4086. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami, M.B.; Haghi, F.P.; Alibabaei, Z.; Enayati, A.A.; Vatandoost, H. First Report of Target Site Insensitivity to Pyrethroids in Human Flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 146, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadón, A.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R.; Martínez, M.A. Use and Abuse of Pyrethrins and Synthetic Pyrethroids in Veterinary Medicine. Vet. J. 2009, 182, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadón, A.; Ares, I.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.-R.; Martínez, M.; Martínez, M.-A. Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids: Ectoparasiticide Use in Veterinary Medicine. In Natural Products; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M.A.; Jacobs, D.E.; Hutchinson, M.J.; Dick, I.G.C. Evaluation of Flea Control Programmes for Cats Using Fenthion and Lufenuron. Vet. Rec. 1996, 138, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, S.R.; Meola, R.W.; Meola, S.M.; Sittertz-Bhatkar, H.; Schenker, R. Mode of Action of Lufenuron on Larval Cat Fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1998, 35, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, S.R.; Meola, R.W.; Meola, S.M.; Sittertz-Bhatkar, H.; Schenker, R. Mode of Action of Lufenuron in Adult Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1999, 36, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.K.; Lance, W.; Hemsarth, H. Synergism of the IGRs Methoprene and Pyriproxyfen Against Larval Cat Fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2016, 53, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meola, R.; Meier, K.; Dean, S.; Bhaskaran, G. Effect of Pyriproxyfen in the Blood Diet of Cat Fleas on Adult Survival, Egg Viability, and Larval Development. J. Med. Entomol. 2000, 37, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, K.G.; Meola, S.M.; Meola, R.W. Mode of Action of Pyriproxyfen and Methoprene on Eggs of Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1993, 30, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gazzar, L.M.; Koehler, P.G.; Patterson, R.S.; Milio, J. Insect Growth Regulators: Mode of Action on the Cat Flea, Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1986, 23, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, M.W.; Denenberg, T.M.; Bunch, S. Control of Fleas on Naturally Infested Dogs and Cats and in Private Residences with Topical Spot Applications of Fipronil or Imidacloprid. Vet. Parasitol. 2000, 93, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlhorn, H.; Mencke, N.; Hansen, O. Effects of Imidacloprid on Adult and Larval Stages of the Flea Ctenocephalides felis after in Vivo and in Vitro Application: A Light- and Electron-Microscopy Study. Parasitol. Res. 1999, 85, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuskiv, I.D.; Tishyn, O.L.; Yuskiv, L.L. A Medical Drug Based on Fipronil, Dinotefuran, and Pyriproxyfen for Treatment of Ectoparasitic Infestations of Dogs and Cats. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2025, 16, e25089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.T.; Hsu, W.H.; Abu-Basha, E.A.; Martin, R.J. Insect Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists as Flea Adulticides in Small Animals. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 33, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.E.; Hutchinson, M.J.; Ryan, W.G. Control of Flea Populations in a Simulated Home Environment Model Using Lufenuron, Imidacloprid or Fipronil. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2001, 15, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugnet, F.; Franc, M. Results of a European Multicentric Field Efficacy Study of Fipronil-(S) Methoprene Combination on Flea Infestation of Dogs and Cats during 2009 Summer. Parasite 2010, 17, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poché, D.M.; Hartman, D.; Polyakova, L.; Poché, R.M. Efficacy of a Fipronil Bait in Reducing the Number of Fleas (Oropsylla spp.) Infesting Wild Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs. J. Vector Ecol. 2017, 42, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy, M.G.; Six, R.H.; Thomas, C.A.; Novotny, M.J.; Smothers, C.D.; Rowan, T.G.; Jernigan, A.D. Efficacy and Safety of Selamectin against Fleas and Heartworms in Dogs and Cats Presented as Veterinary Patients in North America. Vet. Parasitol. 2000, 91, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTier, T.L.; Shanks, D.J.; Jernigan, A.D.; Rowan, T.G.; Jones, R.L.; Murphy, M.G.; Wang, C.; Smith, D.G.; Holbert, M.S.; Blagburn, B.L. Evaluation of the Effects of Selamectin against Adult and Immature Stages of Fleas (Ctenocephalides felis felis) on Dogs and Cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2000, 91, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolken, S.; Franc, M.; Bouhsira, E.; Wiseman, S.; Hayes, B.; Schnitzler, B.; Jacobs, D.E. Evaluation of Spinosad for the Oral Treatment and Control of Flea Infestations on Dogs in Europe. Vet. Rec. 2012, 170, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.E.; Meyer, J.; Zimmermann, A.G.; Qiao, M.; Gissendanner, S.J.; Cruthers, L.R.; Slone, R.L.; Young, D.R. Preliminary Studies on the Effectiveness of the Novel Pulicide, Spinosad, for the Treatment and Control of Fleas on Dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 150, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Young, D.R.; Qureshi, T.; Zoller, H.; Heckeroth, A.R. Fluralaner, a Novel Isoxazoline, Prevents Flea (Ctenocephalides felis) Reproduction in Vitro and in a Simulated Home Environment. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoop, W.L.; Hartline, E.J.; Gould, B.R.; Waddell, M.E.; McDowell, R.G.; Kinney, J.B.; Lahm, G.P.; Long, J.K.; Xu, M.; Wagerle, T.; et al. Discovery and Mode of Action of Afoxolaner, a New Isoxazoline Parasiticide for Dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 201, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTier, T.L.; Chubb, N.; Curtis, M.P.; Hedges, L.; Inskeep, G.A.; Knauer, C.S.; Menon, S.; Mills, B.; Pullins, A.; Zinser, E.; et al. Discovery of Sarolaner: A Novel, Orally Administered, Broad-Spectrum, Isoxazoline Ectoparasiticide for Dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 222, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.E. Lotilaner—A Novel Systemic Tick and Flea Control Product for Dogs. Parasite Vectors 2017, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Baker, C.; Wang, H.; Targa, N.; Pfefferkorn, A.; Tielemans, E. Target Animal Safety Evaluation of a Novel Topical Combination of Esafoxolaner, Eprinomectin and Praziquantel for Cats. Parasite 2021, 28, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hohman, A.E.; Hsu, W.H. Current Review of Isoxazoline Ectoparasiticides Used in Veterinary Medicine. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, M.W. Flea and Tick Control in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halos, L.; Beugnet, F.; Cardoso, L.; Farkas, R.; Franc, M.; Guillot, J.; Pfister, K.; Wall, R. Flea Control Failure? Myths and Realities. Trends Parasitol. 2014, 30, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.B.; Dryden, M.W. Insecticide/Acaricide Resistance in Fleas and Ticks Infesting Dogs and Cats. Parasite Vectors 2014, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.K.; Vetter, R.; Denholm, I.; Blagburn, B.; Williamson, M.S.; Kopp, S.; Coleman, G.; Hostetler, J.; Davis, W.; Mencke, N.; et al. Susceptibility of Adult Cat Fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) to Insecticides and Status of Insecticide Resistance Mutations at the Rdl and Knockdown Resistance Loci. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, S.; Zhang, H.; Lempérière, G. A Review of Control Methods and Resistance Mechanisms in Stored-Product Insects. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2012, 102, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossard, R.L.; Hinkle, N.C.; Rust, M.K. Review of Insecticide Resistance in Cat Fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1998, 35, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, L.E.; Egli, M.; Richardson, A.K.; Brooker, A.; Perkins, R.; Collins, C.M.T.; Cardwell, J.M.; Barron, L.P.; Waage, J. Dog Swimming and Ectoparasiticide Water Contamination in Urban Conservation Areas: A Case Study on Hampstead Heath, London. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.P.; Bauerfeldt, G.F.; Castro, R.N.; Magalhães, V.S.; Alves, M.C.C.; Scott, F.B.; Cid, Y.P. Determination of Fipronil and Fipronil-Sulfone in Surface Waters of the Guandu River Basin by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 108, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.S.P.; Santos, L.F.S.; Navickiene, S. Determination of Pesticide Residues in Ectoparasiticide-Impregnated Collars Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Biomedical. Chromatogr. 2025, 39, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, L.; Oliva, M.; Nobile, M.; Carere, M.; Chiesa, L.M.; Degl’Innocenti, D.; Lacchetti, I.; Mancini, L.; Meucci, V.; Pretti, C.; et al. Environmental Risks and Toxicity of Fipronil and Imidacloprid Used in Pets Ectoparasiticides. Animals 2025, 15, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, K.H.C.; Buchbauer, G. Handbook of Essential Oils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780429141065. [Google Scholar]

- Miresmailli, S.; Isman, M.B. Botanical Insecticides Inspired by Plant–Herbivore Chemical Interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological Effects of Essential Oils—A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.C.; Cid, Y.P.; De Almeida, A.P.; Prudêncio, E.R.; Riger, C.J.; De Souza, M.A.; Coumendouros, K.; Chaves, D.S. In Vitro Efficacy of Essential Oils and Extracts of Schinus molle L. against Ctenocephalides felis felis. Parasitology 2016, 143, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.; Agostini, G.; Agostini, F.; Atti dos Santos, A.C.; Rossato, M. Variation in the Essential Oils Composition in Brazilian Populations of Schinus molle L. (Anacardiaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013, 48, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A.d.S.; Alves, M.d.S.; da Silva, L.C.P.; Patrocínio, D.d.S.; Sanches, M.N.; Chaves, D.S.d.A.; de Souza, M.A.A. Volatiles Composition and Extraction Kinetics from Schinus Terebinthifolius and Schinus Molle Leaves and Fruit. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2015, 25, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina, H.; Lima, P.; Kaplan, M.C.; Valéria De Mello Cruz, A. Influence of Abiotic Factors on Terpenoids Production and Variability in the Plants. Floresta Ambiente 2003, 10, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jerković, I.; Mastelić, J.; Miloš, M. The Impact of Both the Season of Collection and Drying on the Volatile Constituents of Origanum vulgare L. ssp. hirtum Grown Wild in Croatia. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneton, J. Pharmacognosy: Phytochemistry, Medicinal Plants; Editions Médicales: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, J.V.B.; de Almeida Chaves, D.S.; de Souza, M.A.A.; Riger, C.J.; Lambert, M.M.; Campos, D.R.; Moreira, L.O.; dos Santos Siqueira, R.C.; de Paulo Osorio, R.; Boylan, F.; et al. In Vitro Activity of Essential Oils against Adult and Immature Stages of Ctenocephalides felis felis. Parasitology 2020, 147, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevy, J.P.; Bessiere, J.M.; Dherbomez, M.; Millogo, J.; Viano, J. Chemical Composition and Some Biological Activities of the Volatile Oils of a Chemotype of Lippia Chevalieri Moldenke. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, E.J.A.; Carvalho, F.C.; de Castro Oliveira, J.A.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Scotti, M.T.; Silveira, C.H.; Guedes, F.C.; Melo, J.O.F.; de Melo-Minardi, R.C.; de Lima, L.H.F. Elucidating the Molecular Mechanisms of Essential Oils’ Insecticidal Action Using a Novel Cheminformatics Protocol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.; Rogalska, J.; Wyszkowska, J.; Stankiewicz, M. Molecular Targets for Components of Essential Oils in the Insect Nervous System—A Review. Molecules 2017, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, A.; Yan, D.; Ouyang, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Overview of Mechanisms and Uses of Biopesticides. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2021, 67, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.E.; Gostin, I.N.; Blidar, C.F. An Overview of the Mechanisms of Action and Administration Technologies of the Essential Oils Used as Green Insecticides. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1195–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R. Beyond Mosquitoes—Essential Oil Toxicity and Repellency against Bloodsucking Insects. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 117, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R. History, Presence and Perspective of Using Plant Extracts as Commercial Botanical Insecticides and Farm Products for Protection against Insects—A Review. Plant Prot. Sci. 2016, 52, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellse, L.; Wall, R. The Use of Essential Oils in Veterinary Ectoparasite Control: A Review. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2014, 28, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.E.; Mohafrash, S.M.M.; Mikhail, M.W.; Mossa, A.T.H. Development and Evaluation of Clove and Cinnamon Oil-Based Nanoemulsions against Adult Fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 47, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrha, S.; Christenson, J.K.; McEwen, J.; Tesfaye, W.; Vaz Nery, S.; Chang, A.Y.; Spelman, T.; Kosari, S.; Kigen, G.; Carroll, S.; et al. Treatment of Tungiasis Using a Tea Tree Oil-Based Gel Formulation: Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Proof-of-Principle Trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceição, C.L.; Marré, E.O.; da Silva, Y.H.; de Oliveira Santos, L.; Guimarães, B.G.; e Silva, T.M.; da Silva, M.E.C.; Campos, D.R.; Scott, F.B.; Coumendouros, K. In Vitro Evaluation of the Activity of Cinnamaldehyde as an Inhibitor of the Biological Cycle of Ctenocephalides felis felis. Rev. Bras. Med. Vet. 2023, 45, e005123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, E.F.M.S.; Carlos, D.F.L.P.; Epifanio, N.M.d.M.; Coumendouros, K.; Cid, Y.P.; Chaves, D.S.d.A.; Campos, D.R. Insecticidal Activity of Essential Oil of Cannabis Sativa against the Immature and Adult Stages of Ctenocephalides felis felis. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2023, 32, e015122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, C.L.; de Morais, L.A.S.; Campos, D.R.; Chaves, J.K.d.O.; dos Santos, G.C.M.; Cid, Y.P.; de Sousa, M.A.A.; Scott, F.B.; Chaves, D.S.A.; Coumendouros, K. Evaluation of Insecticidal Activity of Thyme, Oregano, and Cassia Volatile Oils on Cat Flea. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2020, 30, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.A.S.; Campos, D.R.; Soares, E.F.M.S.; Fortunato, A.B.R.; e Silva, T.M.; Pereira, N.d.F.; Chaves, D.S.d.A.; Cid, Y.P.; Coumendouros, K. Insecticidal and Repellent Activity of Essential Oils from Copaifera Reticulata, Citrus Paradisi, Lavandula Hybrida and Salvia Sclarea Against Immature and Adult Stages of Ctenocephalides felis felis. Acta Parasitol. 2024, 69, 1426–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, F.D.d.F.L.; de Souza, B.A.; Campos, D.R.; Camargo, N.S.; Riger, C.J.; Cid, Y.P.; Simas, N.K.; Barreto, A.d.S.; Junior, R.G.d.O.; Chaves, D.S.d.A. Evaluation of the Pulicidal Potential of the Essential Oil of Curcuma Zedoaria. Phytochem. Lett. 2024, 61, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J.P.; De Jesus, I.L.R.; De Oliveira Chaves, J.K.; Gijsen, I.S.; Campos, D.R.; Baptista, D.P.; Ferreira, T.P.; Alves, M.C.C.; Coumendouros, K. Efficacy and Residual Effect of Lilicium verum (Star Anise) and Pelargonium graveoiens (Rose Geranium) Essential Oil on Cat Fleas Ctenocephaiides feiis feiis. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30, e009321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadee, P.; Chansakaow, S.; Tipduangta, P.; Tadee, P.; Khaodang, P.; Chukiatsiri, K. Essential Oil Pharmaceuticals for Killing Ectoparasites on Dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 25, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.d.F.; de Souza, B.A.; Campos, D.R.; Camargo, N.S.; Carlos, D.F.L.P.; Cruz, T.d.A.; Riger, C.J.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Cid, Y.P.; Chaves, D.S.d.A. Evaluation of Essential Oils from the Brazilian Species Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC. and Mimosa verrucosa Benth. against Ctenocephalides felis felis Bouché. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2025, 68, e25240095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, J.A.e.S.; Machado, D.d.B.; Felisberto, J.S.; Chaves, D.S.d.A.; Campos, D.R.; Cid, Y.P.; Sadgrove, N.J.; Ramos, Y.J.; Moreira, D.d.L. Insecticidal Activity of Essential Oils from Piper Aduncum against Ctenocephalides felis felis: A Promising Approach for Flea Control. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2024, 33, e007624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Temperini, M.B.; Fortunato, A.B.R.; Campos, D.R.; de Jesus, I.L.R.; Cid, Y.P.; Scott, F.B.; Coumendouros, K. Insecticidal Activity in Vitro of the Essential Oil of Pogostemon Cablin against Ctenocephalides felis felis. Rev. Bras. Med. Vet. 2022, 44, e003422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.M.; Campos, D.R.; Borges, D.A.; de Avelar, B.R.; Ferreira, T.P.; Cid, Y.P.; Boylan, F.; Scott, F.B.; de Almeida Chaves, D.S.; Coumendouros, K. Activity of Syzygium Aromaticum Essential Oil and Its Main Constituent Eugenol in the Inhibition of the Development of Ctenocephalides felis felis and the Control of Adults. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 282, 109126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, M.C.; Dietrich, G.; Panella, N.A.; Montenieri, J.A.; Karchesy, J.J. Biocidal Activity of Three Wood Essential Oils against Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae), Xenopsylla cheopis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae), and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.R.; Mikhail, M.W.; Hassan, M.E. Efficacy of Essential Oils Extracted From Cinnamon and Rosemary against the Rat Fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) and Evaluate Their Effects on Some Vital Processes in Rat Fleas and Albino Rat. Egypt J. Chem. 2024, 67, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.R.; Mikhail, M.W. Laboratory Evaluation of Essential Oils Extracted From Peppermint and Eucalyptus Plants Against the Rat Flea (Xynopsylla cheopis) and Evaluate Their Effects on Some Vital Process in Albino Rat. J. Med. Sci. Res. 2024, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.M.; de Almeida Chaves, D.S.; Raquel de Jesus, I.L.; Miranda, F.R.; Ferreira, T.P.; Nunes e Silva, C.; de Souza Alves, N.; Alves, M.C.C.; Avelar, B.R.; Scott, F.B.; et al. Ocimum gratissimum Essential Oil and Eugenol against Ctenocephalides felis felis and Rhipicephalus sanguineus: In Vitro Activity and Residual Efficacy of a Eugenol-Based Spray Formulation. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 309, 109771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus, I.L.R.; Miranda, F.R.; Ferreira, T.P.; Nascimento, A.O.D.; Lima, K.K.d.S.d.; de Avelar, B.R.; Campos, D.R.; Cid, Y.P. Bioactive-Based Spray and Spot-on Formulations: Development, Characterization and in Vitro Efficacy against Fleas and Ticks. Exp. Parasitol. 2025, 269, 108881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panella, N.A.; Dolan, M.C.; Karchesy, J.J.; Xiong, Y.; Peralta-cruz, J.; Khasawneh, M.; Montenieri, J.A.; Maupin, G.O. Use of Novel Compounds for Pest Control: Insecticidal and Acaricidal Activity of Essential Oil Components from Heartwood of Alaska Yellow Cedar. J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.C.; Huang, C.G.; Chang, S.T.; Yang, S.H.; Hsu, S.H.; Wu, W.J.; Huang, R.N. An Improved Bioassay Facilitates the Screening of Repellents against Cat Flea, Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest. Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, L.C.; Lawson, M.A.; Young, L.L. Tests of Repellents Against Diamanus montanus (Siphonaptera: Ceratophyllidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1982, 19, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, M.B.; Poorrastgoo, F.; Taghiloo, B.; Mohammadi, J. Original Article Repellency Effect of Essential Oils of Some Native Plants and Synthetic Repellents against Human Flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2017, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bisht, N.; Fular, A.; Ghosh, S.; Nanyiti, S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Acaricidal Properties of Plant Derived Products against Ixodid Ticks Population. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.M.D.L.; Martins, V.E.P. Óleos Essenciais e Extratos Vegetais Como Ferramentas Alternativas Ao Controle Químico de Larvas de Aedes spp., Anopheles spp. e Culex spp. J. Health Biol. Sci. 2022, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyuga, A.; Ouma, P.; Matharu, A.K.; Krücken, J.; Kaneko, S.; Goto, K.; Fillinger, U. Myth or Truth: Investigation of the Jumping Ability of Tunga penetrans (Siphonaptera: Tungidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2024, 61, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R. Essential Oils for the Development of Eco-Friendly Mosquito Larvicides: A Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadollahi, A.; Ziaee, M.; Palla, F. Essential Oils Extracted from Different Species of the Lamiaceae Plant Family as Prospective Bioagents against Several Detrimental Pests. Molecules 2020, 25, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzza, R.C.; Baumgratz, J.F.A.; Bicudo, C.E.M.; Canhos, D.A.L.; Carvalho, A.A.; Coelho, M.A.N.; Costa, A.F.; Costa, D.P.; Hopkins, M.G.; Leitman, P.M.; et al. New Brazilian Floristic List Highlights Conservation Challenges. Bioscience 2012, 62, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil Flora Group Brazilian Flora 2020:Innovation and Collaboration to Meet Target 1 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC). Rodriguésia 2018, 69, 1513–1527. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-S.; Lee, H.-S. Acaricidal and Insecticidal Responses of Cinnamomum Cassia Oils and Main Constituents. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2018, 61, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moungthipmalai, T.; Puwanard, C.; Aungtikun, J.; Sittichok, S.; Soonwera, M. Ovicidal Toxicity of Plant Essential Oils and Their Major Constituents against Two Mosquito Vectors and Their Non-Target Aquatic Predators. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aungtikun, J.; Soonwera, M. Improved Adulticidal Activity against Aedes aegypti (L.) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) from Synergy between Cinnamomum spp. Essential Oils. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Khanikor, B.; Sarma, R. Persistent Susceptibility of Aedes aegypti to Eugenol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasen, K.; Wongsrila, A.; Prathumtet, J.; Sriraj, P.; Boonmars, T.; Promsrisuk, T.; Laikaew, N.; Aukkanimart, R. Bio Efficacy of Cinnamaldehyde from Cinnamomum verum Essential Oil against Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Entomol. Acarol. Res. 2021, 53, 9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Sahu, U.; Karthik, P.; Vendan, S.E. Eugenol Nanoemulsion as Bio-Fumigant: Enhanced Insecticidal Activity against the Rice Weevil, Sitophilus Oryzae Adults. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazolin, M.; Bizzo, H.R.; Monteiro, A.F.M.; Lima, M.E.C.; Maisforte, N.S.; Gama, P.E. Synergism in Two-Component Insecticides with Dillapiole against Fall Armyworm. Plants 2023, 12, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Méndez, L.Y.; Sanabria-Flórez, P.L.; Saavedra-Reyes, L.M.; Merchan-Arenas, D.R.; Kouznetsov, V.V. Bioactivity of Semisynthetic Eugenol Derivatives against Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Larvae Infesting Maize in Colombia. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Filho, A.A.; do Vale, V.F.; de Oliveira Monteiro, C.M.; Barrozo, M.M.; Stanton, M.A.; Yamaguchi, L.F.; Kato, M.J.; Araújo, R.N. Effects of Piper aduncum (Piperales: Piperaceae) Essential Oil and Its Main Component Dillapiole on Detoxifying Enzymes and Acetylcholinesterase Activity of Amblyomma sculptum (Acari: Ixodidae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzile, A.-S.; Majerus, S.L.; Podeszfinski, C.; Guillet, G.; Durst, T.; Arnason, J.T. Dillapiol Derivatives as Synergists: Structure–Activity Relationship Analysis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2000, 66, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herms, D.A.; McCullough, D.G. Emerald Ash Borer Invasion of North America: History, Biology, Ecology, Impacts, and Management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014, 59, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B.; Machial, C.M. Chapter 2 Pesticides Based on Plant Essential Oils: From Traditional Practice to Commercialization. Adv. Phytomed. 2006, 3, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pavoni, L.; Perinelli, D.R.; Bonacucina, G.; Cespi, M.; Palmieri, G.F. An Overview of Micro- and Nanoemulsions as Vehicles for Essential Oils: Formulation, Preparation and Stability. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossetin, L.F.; Garlet, Q.I.; Velho, M.C.; Gündel, S.; Ourique, A.F.; Heinzmann, B.M.; Monteiro, S.G. Development of Nanoemulsions Containing Lavandula dentata or Myristica fragrans Essential Oils: Influence of Temperature and Storage Period on Physical-Chemical Properties and Chemical Stability. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 160, 113115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioli Montoto, S.; Muraca, G.; Ruiz, M.E. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Pharmacological and Biopharmaceutical Aspects. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 587997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, A.G.; McLean, M.K.; Khan, S.A. Adverse Reactions from Essential Oil-containing Natural Flea Products Exempted from Environmental Protection Agency Regulations in Dogs and Cats. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2012, 22, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Noland, E.; Rosser, E.; Petersen, A. Sterile Neutrophilic Dermatitis in a Cat Associated with a Topical Plant-derived Oil Flea Preventative. Vet. Dermatol. 2022, 33, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flea Species | Essential Oil/Bioactive Compounds | Botanical Family/Chemical Class | Type of Bioassay | Effective Concentration | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctenocephalides felis | Cinnamomum brevipedunculatum | Lauraceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 60% lasting up to 1 h | [141] |

| Cinnamomum osmophloeum | Lauraceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 90% lasting up to 8 h | [141] | |

| Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | in vitro | 4% | maximum repellent effect of 60% lasting up to 1 h | [127] | |

| Citrus tachibana | Rutaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 63.5% lasting up to 1 h | [141] | |

| Citrus taiwanica | Rutaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 65.8% lasting up to 1 h | [141] | |

| Clausena excavata | Rutaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 61.4% lasting up to 1 h | [141] | |

| Copaifera reticulata | Fabaceae | in vitro | 4% | repellent effect greater than 80% lasting up to 3 h. | [127] | |

| Cryptomeria japonica | Cupressaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 55.6% lasting up to 1 h | [141] | |

| Cunninghamia konishii | Cupressaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 58.4% lasting up to 1 h | [141] | |

| Gaultheria cumingiana | Ericaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 54.4% lasting up to 1 h | [141] | |

| Lavandula hybrida | Lamiaceae | in vitro | 4% | repellent effect greater than 80% lasting up to 1 h | [127] | |

| Plectranthus amboinicus | Lamiaceae | in vitro | 0.5% | maximum repellent effect of 60% lasting up to 4 h | [141] | |

| Salvia sclarea | Lamiaceae | in vitro | 4% | repellent effect greater than 80% lasting up to 3 h | [127] | |

| Taiwania cryptomerioides | Cupressaceae | in vitro | 2% | maximum repellent effect of 80% lasting up to 4 h | [141] | |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Phenylpropanoid | in vitro | 2% | repellent effect greater than 90% lasting up to 8 h | [141] | |

| Thymol | Monoterpene | in vitro | 0.5% | repellent effect greater than 90% lasting up to 4 h | [141] | |

| α-cadinol | Sesquiterpene | in vitro | 2% | repellent effect greater than 80% lasting up to 4 h | [141] | |

| Diamanus montanus | Mentha pulegium | Lamiaceae | in vivo | 0.41% | repellent effect greater than 95% after 20 min of exposure | [142] |

| Sassafras albidum | Lauraceae | in vivo | 0.14% | repellent effect greater than 95% after 20 min of exposure | [142] | |

| Pulex irritans | Achilea wilhelmsii | Asteraceae | in vivo | 8% | repellent effect of 87% after 3 min of exposure | [143] |

| Mentha piperita | Lamiaceae | in vivo | 8% | repellent effect of 69% after 3 min of exposure | [143] | |

| Myrtus communis | Myrtaceae | in vivo | 8% | repellent effect of 96% after 3 min of exposure | [143] | |

| Ziziphora tenuiore | Lamiaceae | in vivo | 8% | repellent effect of 98% after 3 min of exposure | [143] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campos, D.R.; de Jesus, I.L.R.; Scott, F.B.; Correia, T.R.; Cid, Y.P. Essential Oils and Bioproducts for Flea Control: A Critical Review. Insects 2025, 16, 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121276

Campos DR, de Jesus ILR, Scott FB, Correia TR, Cid YP. Essential Oils and Bioproducts for Flea Control: A Critical Review. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121276

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampos, Diefrey Ribeiro, Ingrid Lins Raquel de Jesus, Fabio Barbour Scott, Thais Riberio Correia, and Yara Peluso Cid. 2025. "Essential Oils and Bioproducts for Flea Control: A Critical Review" Insects 16, no. 12: 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121276

APA StyleCampos, D. R., de Jesus, I. L. R., Scott, F. B., Correia, T. R., & Cid, Y. P. (2025). Essential Oils and Bioproducts for Flea Control: A Critical Review. Insects, 16(12), 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121276