Characterization of Cry4Aa Toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis JW-1 and Its Insecticidal Activity Against Bradysia difformis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Culture Conditions

2.3. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

2.4. Cry4Aa Gene Analysis

2.5. Expression Vector Construction

2.6. Purification of the Cry4Aa Fusion Protein

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Insecticidal Activity Test

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification

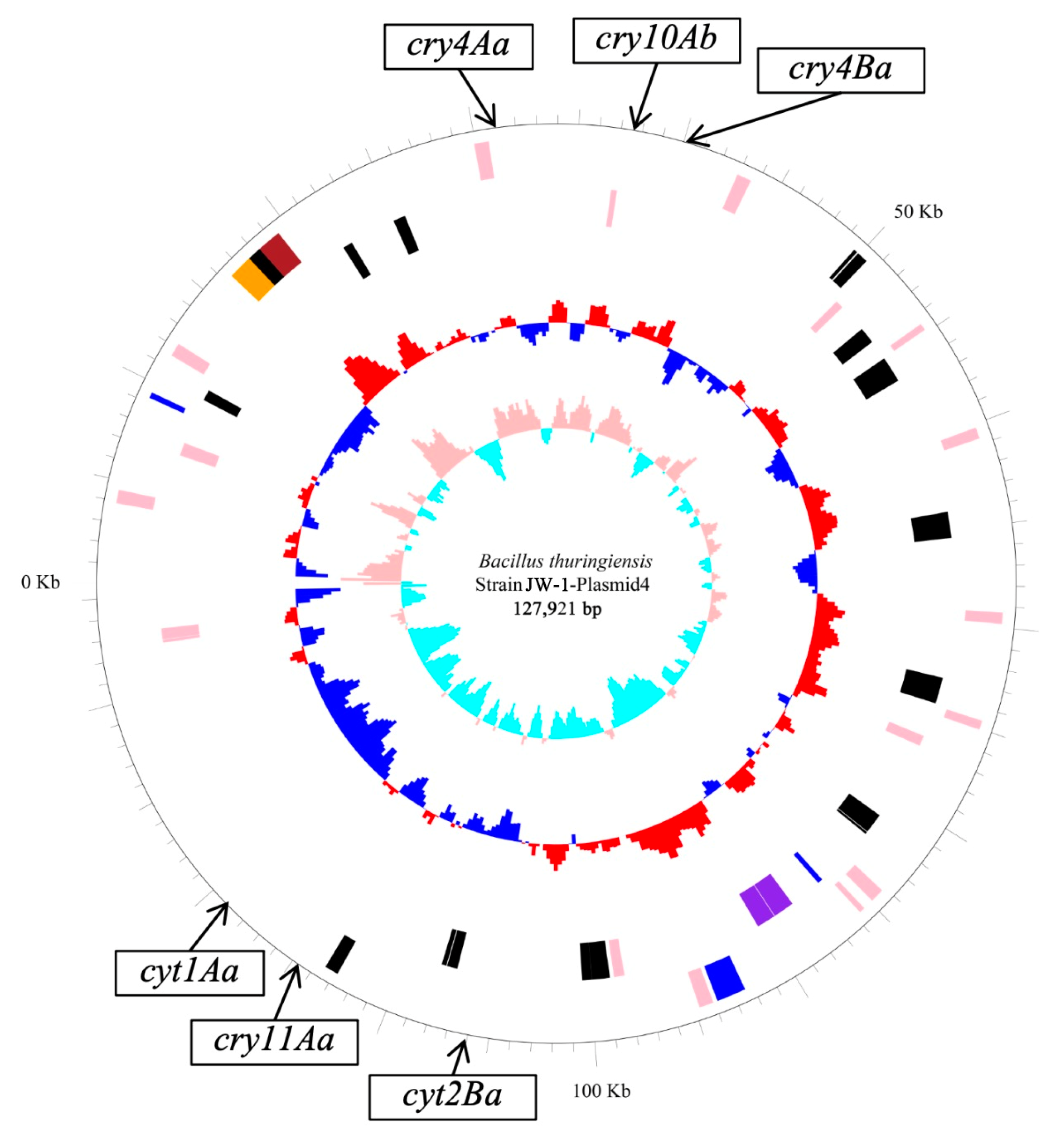

3.2. Genome Properties

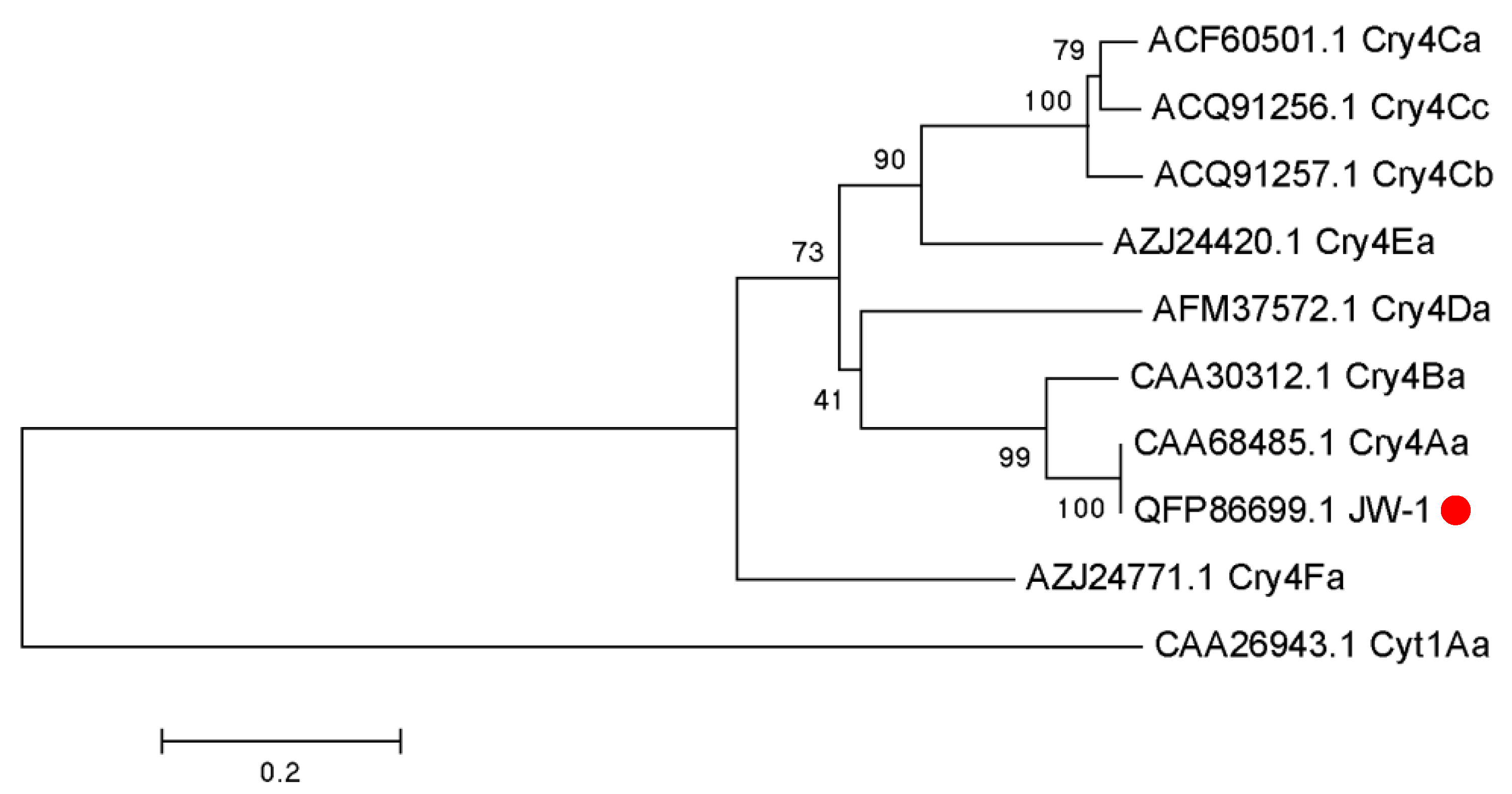

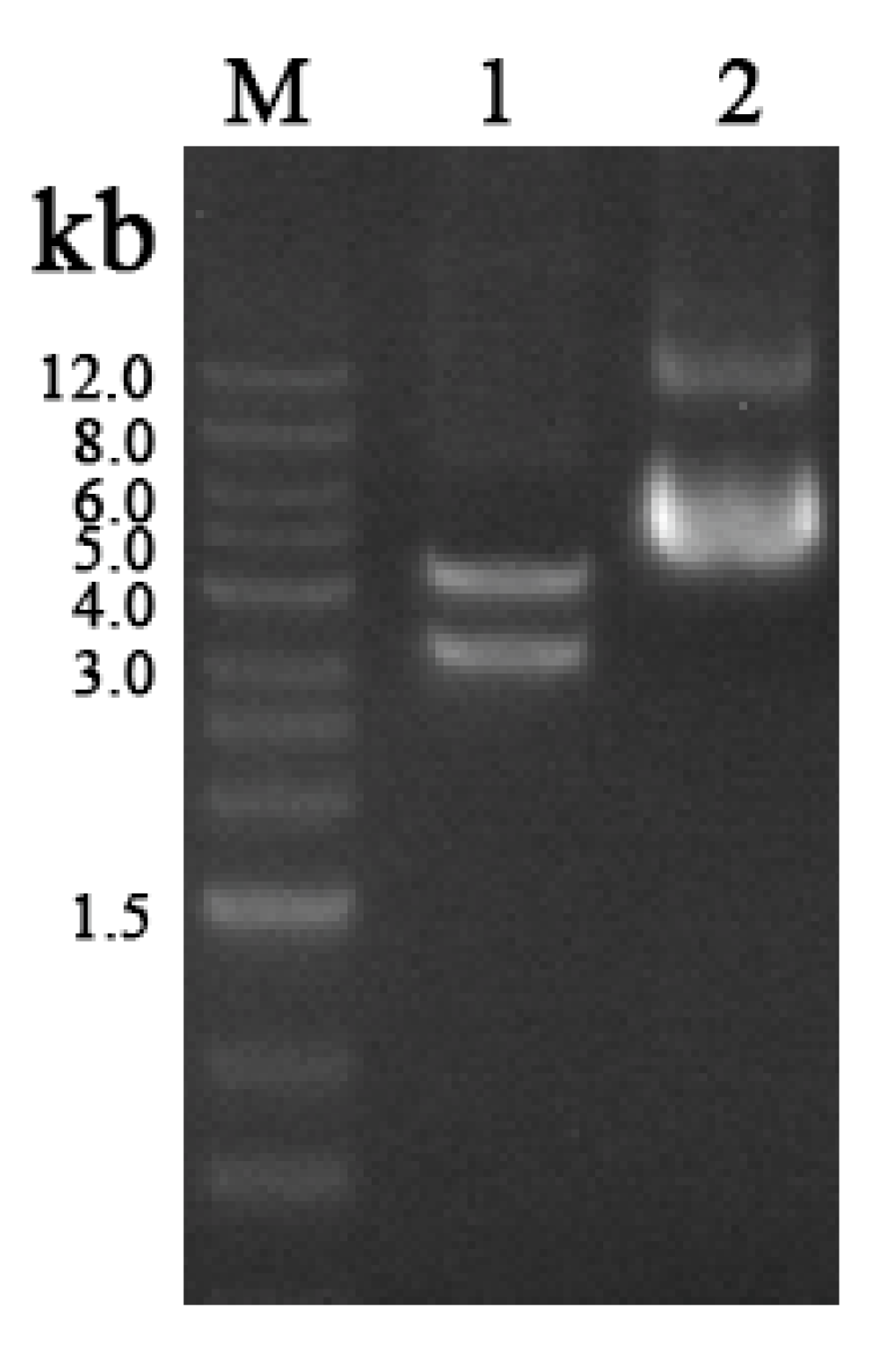

3.3. PCR Amplification of cry4 Genes

3.4. Expression Vector Assembly

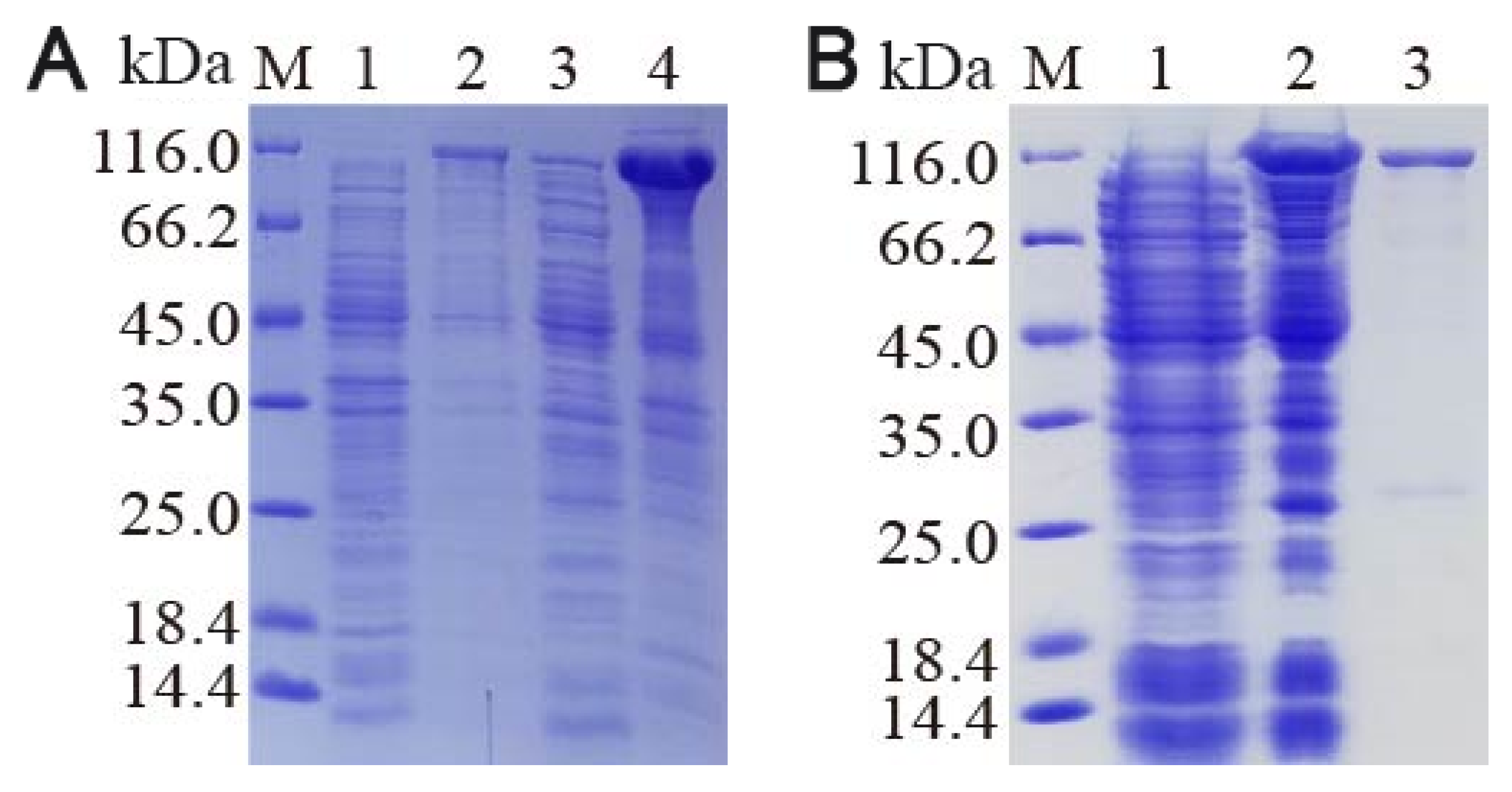

3.5. Stimulated Expression

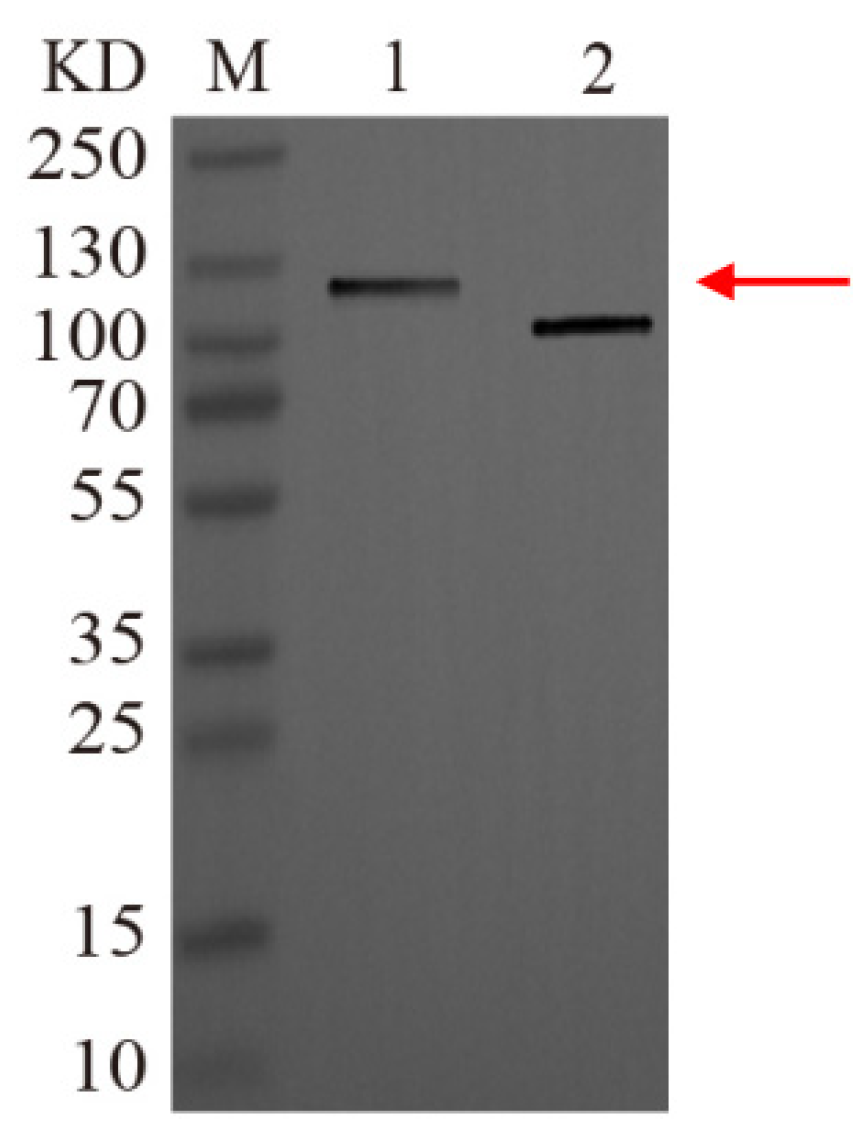

3.6. Recombinant Protein Isolation and Western Blot Confirmation

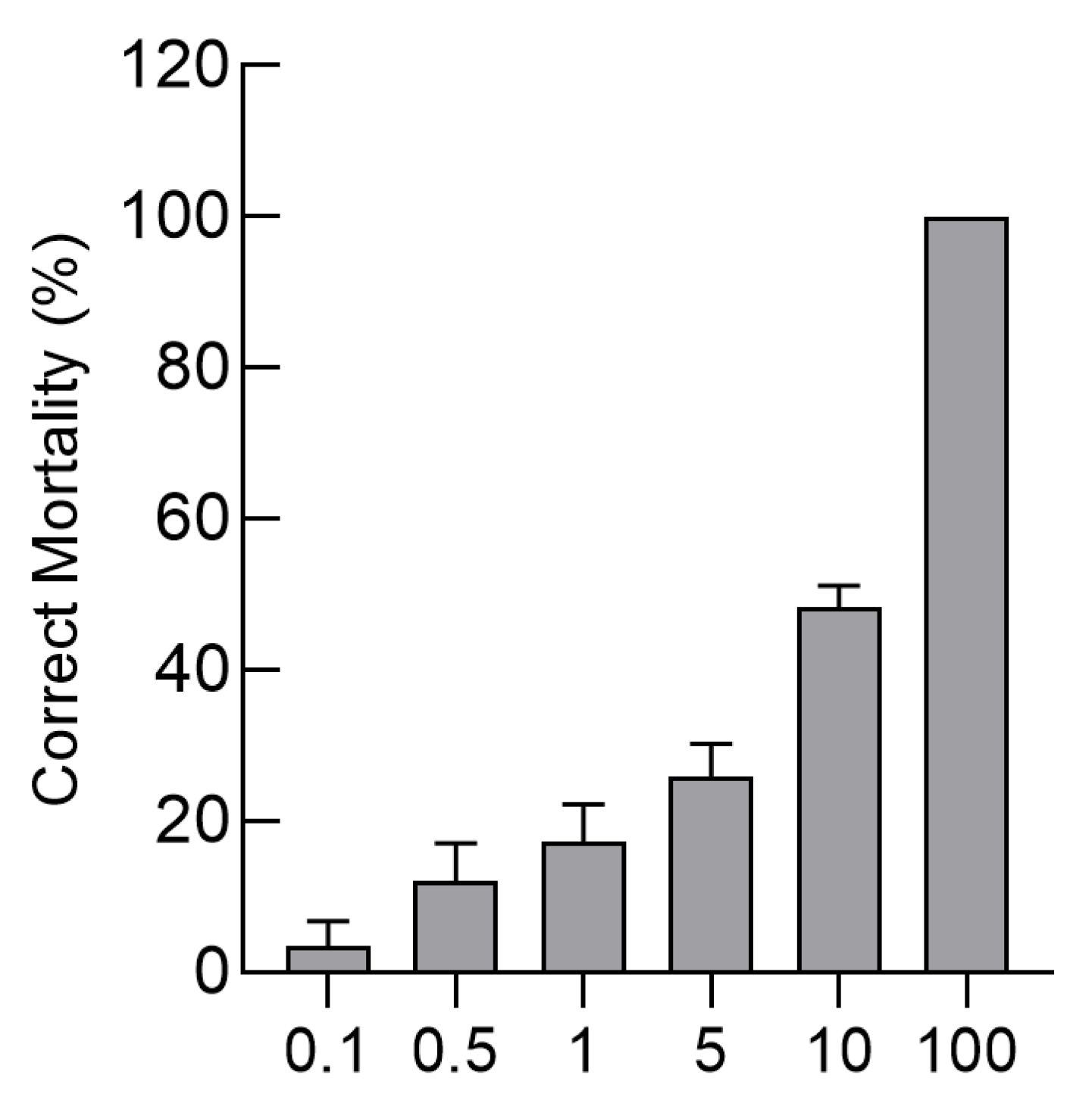

3.7. Bioassay-Based Analysis of Cry4Aa Toxin Activity

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Xu, S. Edible mushroom industry in China: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3949–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-X.; Tang, C.-H.; Tan, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, Y.-F.; Zhang, H.-A.; Zhang, J.-S. Progress in physical mutagenesis breeding of Ganoderma spp. in the last five years. Acta Edulis Fungi 2023, 30, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkhalek, S.T.; Moussa, M.A.; Izah, S.C.; Zia, S.; Naeem, A.; Wang, M.-Q. Integrated Pest Management in Edible Mushroom Cultivation. In Bioactive Compounds in Edible Mushrooms: Sustainability and Health Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 47–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Leng, R.; Huang, J.; Qu, C.; Wu, H. Review of three black fungus gnat species (Diptera: Sciaridae) from greenhouses in China: Three greenhouse sciarids from China. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Xue, M.; Luo, Y.; Ji, G.; Liu, F.; Zhao, H.; Sun, X. Effects of short-term heat shock and physiological responses to heat stress in two Bradysia adults, Bradysia odoriphaga and Bradysia difformis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Wang, G.; Quandahor, P.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C. Effects of sex ratio on adult fecundity, longevity and egg hatchability of Bradysia difformis Frey at different temperatures. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erler, F.; Bayram, Y. Mass trapping using a new-designed light trap as a viable alternative to insecticides for the management of dipteran pests of cultivated mushrooms. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.; van Rijn, P.C. Pesticides do not significantly reduce arthropod pest densities in the presence of natural enemies. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 2010–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragasruthi, M.; Balakrishnan, N.; Murugan, M.; Swarnakumari, N.; Harish, S.; Sharmila, D.J.S. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)-based biopesticide: Navigating success, challenges, and future horizons in sustainable pest control. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo-López, L.; Soberón, M.; Bravo, A. Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal three-domain Cry toxins: Mode of action, insect resistance and consequences for crop protection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, A.; Likitvivatanavong, S.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Bacillus thuringiensis: A story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtierra-de-Luis, D.; Villanueva, M.; Berry, C.; Caballero, P. Potential for Bacillus thuringiensis and other bacterial toxins as biological control agents to combat dipteran pests of medical and agronomic importance. Toxins 2020, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Arrizabalaga, M.; Villanueva, M.; Escriche, B.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C.; Caballero, P. Insecticidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis proteins against coleopteran pests. Toxins 2020, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Yang, C.J.; Li, N.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.M.; Yi, S.J.; Li, Z.Q.; Adang, M.J.; Huang, G.H. Novel strategies for the biocontrol of noctuid pests (Lepidoptera) based on improving ascovirus infectivity using Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Sci. 2021, 28, 1452–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansinenea, E. Applications and patents of Bacillus spp. in agriculture. In Intellectual Property Issues in Microbiology; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.; Schatz, M.C.; Walenz, B.P.; Martin, J.; Howard, J.T.; Ganapathy, G.; Wang, Z.; Rasko, D.A.; McCombie, W.R.; Jarvis, E.D. Hybrid error correction and de novo assembly of single-molecule sequencing reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalitha, S. Primer premier 5. Biotech Softw. Internet Rep. 2000, 1, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.-F.; Qu, S.-X.; Lin, J.-S.; Li, H.-P.; Hou, L.-J.; Jiang, N.; Luo, X.; Ma, L. Identification of Cyt2Ba from a new strain of Bacillus thuringiensis and its toxicity in Bradysia difformis. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2859–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.-F.; Qu, S.-X.; Lin, J.-S.; Li, H.-P.; Hou, L.-J.; Jiang, N.; Luo, X.; Ma, L.; Han, J.-C. Screening of Bacillus thuringiensis and identification of insecticidal crystal protein gene against Bradysia difformis in mushroom cultivation. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric. Life Sci.) 2019, 45, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.; O’Neil, S.; Ben-Dov, E.; Jones, A.F.; Murphy, L.; Quail, M.A.; Holden, M.T.G.; Harris, D.; Zaritsky, A.; Parkhill, J. Complete sequence and organization of pBtoxis, the toxin-coding plasmid of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5082–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, A.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 2007, 49, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigott, C.R.; Ellar, D.J. Role of receptors in Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin activity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwick, M.E.; Joseph, S.J.; Didelot, X.; Chen, P.E.; Bishop-Lilly, K.A.; Stewart, A.C.; Willner, K.; Nolan, N.; Lentz, S.; Thomason, M.K. Genomic characterization of the Bacillus cereus sensu lato species: Backdrop to the evolution of Bacillus anthracis. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1512–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crickmore, N.; Berry, C.; Panneerselvam, S.; Mishra, R.; Connor, T.R.; Bonning, B.C. A structure-based nomenclature for Bacillus thuringiensis and other bacteria-derived pesticidal proteins. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 186, 107438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnepf, E.; Crickmore, N.; Van Rie, J.; Lereclus, D.; Baum, J.; Feitelson, J.; Zeigler, D.; Dean, D. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 775–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonserm, P.; Mo, M.; Angsuthanasombat, C.; Lescar, J. Structure of the functional form of the mosquito larvicidal Cry4Aa toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at a 2.8-angstrom resolution. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazit, E.; Rocca, P.L.; Sansom, M.S.; Shai, Y. The structure and organization within the membrane of the helices composing the pore-forming domain of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin are consistent with an “umbrella-like” structure of the pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 12289–12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntheeranurak, T.; Uawithya, P.; Potvin, L.; Angsuthanasombat, C.; Schwartz, J.-l. Ion channels formed in planar lipid bilayers by the dipteran-specific Cry4B Bacillus thuringiensis toxin and its α1–α5 fragment. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2004, 21, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Tersch, M.; Slatin, S.L.; Kulesza, C.A.; English, L.H. Membrane-permeabilizing activities of Bacillus thuringiensis coleopteran-active toxin CryIIIB2 and CryIIIB2 domain I peptide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 3711–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, F.S.; Slatin, S.L.; Kulesza, C.A.; English, L.H. Ion channel activity of N-terminal fragments from CryIA (c) delta-endotoxin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 196, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, V.; Granero, F.; De Maagd, R.; Bosch, D.; Mensua, J.; Ferre, J. Role of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin domains in toxicity and receptor binding in the diamondback moth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1900–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Adang, M.J. Importance of Cry1 δ-endotoxin domain II loops for binding specificity in Heliothis virescens (L.). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, L.; Tabashnik, B.E.; Mazza, A.; Préfontaine, G.; Potvin, L.; Brousseau, R.; Schwartz, J.-L. Mutagenic analysis of a conserved region of domain III in the Cry1Ac toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, S.L.; Ellar, D.J.; Li, J.; Derbyshire, D.J. N-acetylgalactosamine on the putative insect receptor aminopeptidase N is recognised by a site on the domain III lectin-like fold of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 287, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maagd, R.A.; Bakker, P.; Staykov, N.; Dukiandjiev, S.; Stiekema, W.; Bosch, D. Identification of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1C domain III amino acid residues involved in insect specificity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 4369–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagiwa, M.; Esaki, M.; Otake, K.; Inagaki, M.; Komano, T.; Amachi, T.; Sakai, H. Activation process of dipteran-specific insecticidal protein produced by Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 3464–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taveecharoenkool, T.; Angsuthanasombat, C.; Kanchanawarin, C. Combined molecular dynamics and continuum solvent studies of the pre-pore Cry4Aa trimer suggest its stability in solution and how it may form pore. PMC Biophys. 2010, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, T.; Howlader, M.T.H.; Yamagiwa, M.; Sakai, H. Design and construction of a synthetic Bacillus thuringiensis Cry4Aa gene: Hyperexpression in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 80, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, T.; Yoneda, N.; Okada, K.; Higaki, A.; Howlader, M.T.H.; Ide, T. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry11Ba works synergistically with Cry4Aa but not with Cry11Aa for toxicity against mosquito Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2017, 52, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruk, T.; Avican, U.; Camci, I.Y.; Gedik, S.T. Overexpression of polyphosphate kinase gene (ppk) increases bioinsecticide production by Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soberón, M.; Rodriguez-Almazán, C.; Muñóz-Garay, C.; Pardo-López, L.; Porta, H.; Bravo, A. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt mutants useful to counter toxin action in specific environments and to overcome insect resistance in the field. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 104, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bases (bp) | Gene Number | Gene Total Length (bp) | GC Content in Coding Regions (%) | GenBank Accession No. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JW-1-chromosome | 5,500,376 | 5645 | 4,582,035 | 35.8 | CP045030.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid1 | 359,606 | 340 | 262,059 | 33.5 | CP045023.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid 2 | 349,211 | 449 | 300,957 | 33.7 | CP045024.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid 3 | 235,425 | 247 | 208,911 | 36.6 | CP045025.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid 4 | 127,921 | 131 | 94,935 | 33.9 | CP045026.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid 5 | 14,935 | 28 | 13,209 | 39.8 | CP045027.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid 6 | 6824 | 3 | 2292 | 31.8 | CP045028.1 |

| JW-1-Plasmid 7 | 4974 | 3 | 3045 | 34.5 | CP045029.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, P.; Qu, S.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Hou, L.; Jiang, N.; Ma, L. Characterization of Cry4Aa Toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis JW-1 and Its Insecticidal Activity Against Bradysia difformis. Insects 2025, 16, 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121228

Xu P, Qu S, Lin J, Li H, Hou L, Jiang N, Ma L. Characterization of Cry4Aa Toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis JW-1 and Its Insecticidal Activity Against Bradysia difformis. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121228

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ping, Shaoxuan Qu, Jinsheng Lin, Huiping Li, Lijuan Hou, Ning Jiang, and Lin Ma. 2025. "Characterization of Cry4Aa Toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis JW-1 and Its Insecticidal Activity Against Bradysia difformis" Insects 16, no. 12: 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121228

APA StyleXu, P., Qu, S., Lin, J., Li, H., Hou, L., Jiang, N., & Ma, L. (2025). Characterization of Cry4Aa Toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis JW-1 and Its Insecticidal Activity Against Bradysia difformis. Insects, 16(12), 1228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121228