Beyond Species Averages: Intraspecific Trait Variation Reveals Functional Convergence Under Invasion

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

2.2. Ant Sampling

2.3. Functional Trait Measurements

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Distinct Ant Community Structures Across the Invasion Gradient

3.2. Invader Abundance Drives Decline in Native Richness

3.3. Functional Traits Distributions Reveal Niche Overlap Change and Competitive Filtering

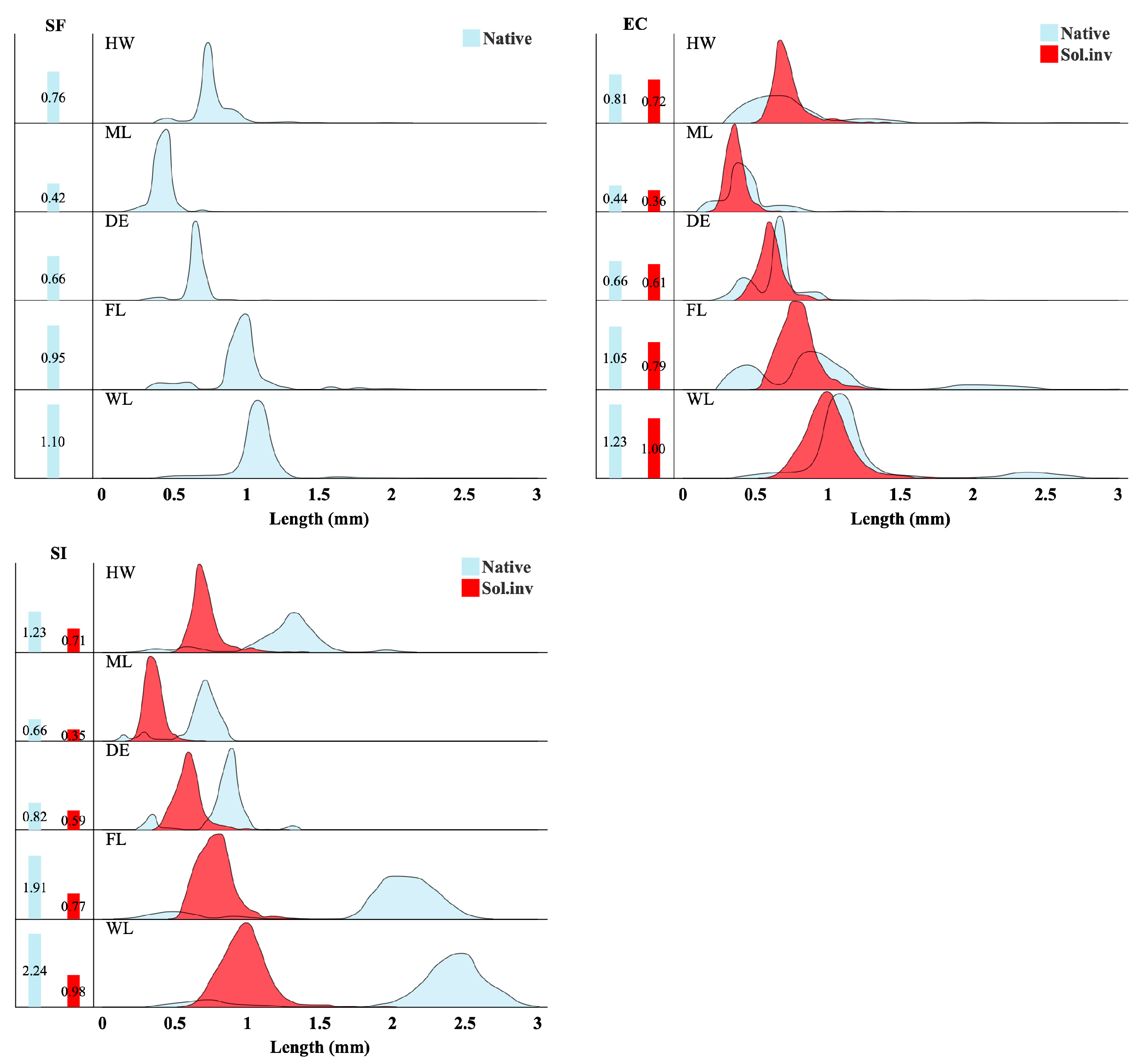

3.4. Species-Specific Trait Shifts as Evidence for Trait Displacement

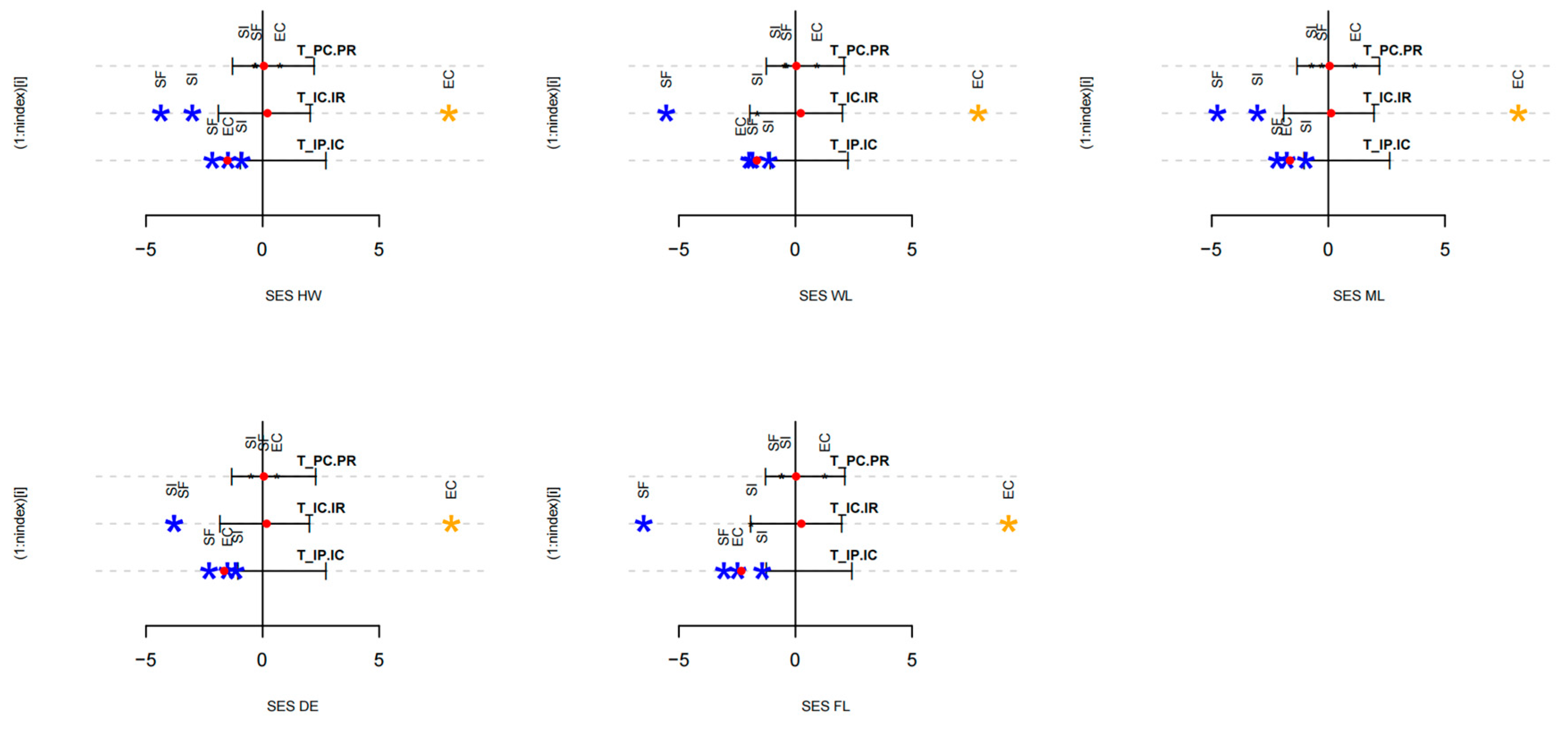

3.5. Hierarchical Analysis Confirms Competitive Filtering as the Dominant Assembly Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vellend, M. Conceptual Synthesis in Community Ecology. Q. Rev. Biol. 2010, 85, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellend, M.; Srivastava, D.S.; Anderson, K.M.; Brown, C.D.; Jankowski, J.E.; Kleynhans, E.J.; Kraft, N.J.B.; Letaw, A.D.; Macdonald, A.A.M.; Maclean, J.E.; et al. Assessing the Relative Importance of Neutral Stochasticity in Ecological Communities. Oikos 2014, 123, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-H.; Yang, J.W.; Liu, A.C.-H.; Lu, H.-P.; Gong, G.-C.; Shiah, F.-K.; Hsieh, C. Community Assembly Processes as a Mechanistic Explanation of the Predator-Prey Diversity Relationship in Marine Microbes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 651565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, B.; Watkins, E.; Lourenço, J.; Gupta, S.; Foster, K.R. Competing Species Leave Many Potential Niches Unfilled. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastore, A.I.; Barabás, G.; Bimler, M.D.; Mayfield, M.M.; Miller, T.E. The Evolution of Niche Overlap and Competitive Differences. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, N.J.; Gotelli, N.J.; Heller, N.E.; Gordon, D.M. Community Disassembly by an Invasive Species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2474–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, N.J.B.; Adler, P.B.; Godoy, O.; James, E.C.; Fuller, S.; Levine, J.M. Community Assembly, Coexistence and the Environmental Filtering Metaphor. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.L.; Lee, R.H.; Leong, C.-M.; Lewis, O.T.; Guénard, B. Trait-Mediated Competition Drives an Ant Invasion and Alters Functional Diversity. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20220504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Martin, J.-L.; Genovesi, P.; Maris, V.; Wardle, D.A.; Aronson, J.; Courchamp, F.; Galil, B.; García-Berthou, E.; Pascal, M.; et al. Impacts of Biological Invasions: What’s What and the Way Forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Invasive Alien Species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.F.; Valerio, F.; Lourenço, R. Incorporating Functional Connectivity into Species Distribution Models Improves the Prediction of Invasiveness of an Exotic Species Not at Niche Equilibrium. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 3517–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, A.; Blanco, C.C.; Pillar, V.D. Disentangling by Additive Partitioning the Effects of Invasive Species on the Functional Structure of Communities. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmquist, A.J.; Adams, S.A.; Gillespie, R.G. Invasion by an Ecosystem Engineer Changes Biotic Interactions between Native and Non-native Taxa. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal-Ornelas, R.; Lockwood, J.L.; Crystal-Ornelas, R.; Lockwood, J.L. The ‘Known Unknowns’ of Invasive Species Impact Measurement. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 1513–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, A.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dick, J.T.A.; Hulme, P.E.; Iacarella, J.C.; Jeschke, J.M.; Liebhold, A.M.; Lockwood, J.L.; MacIsaac, H.J.; et al. Invasion Science: A Horizon Scan of Emerging Challenges and Opportunities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holway, D.A.; Lach, L.; Suarez, A.V.; Tsutsui, N.D.; Case, T.J. The Causes and Consequences of Ant Invasions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 181–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascunce, M.S.; Yang, C.-C.; Oakey, J.; Calcaterra, L.; Wu, W.-J.; Shih, C.-J.; Goudet, J.; Ross, K.G.; Shoemaker, D. Global Invasion History of the Fire Ant Solenopsis invicta. Science 2011, 331, 1066–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Bamisile, B.S.; Fan, R.; Hafeez, M.; Islam, W.; Yang, W.; Wei, M.; Ran, H.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Ant Invasion in China: An in-Depth Analysis of the Country’s Ongoing Battle with Exotic Ants. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Kafle, L.; Shih, C.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Kafle, L.; Shih, C.-J. Interspecific Competition between Solenopsis invicta and Two Native Ant Species, Pheidole iervens and Monomorium chinense. J. Econ. Entomol. 2011, 104, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, H.; Xian, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, B.; Jia, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, W. Geographical Distribution Pattern and Ecological Niche of Solenopsis invicta Buren in China under Climate Change. Diversity 2023, 15, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.L.; Carmona, C.P. Including Intraspecific Trait Variability to Avoid Distortion of Functional Diversity and Ecological Inference: Lessons from Natural Assemblages. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 946–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.L.; Guénard, B.; Lewis, O.T. The Cryptic Impacts of Invasion: Functional Homogenization of Tropical Ant Communities by Invasive Fire Ants. Oikos 2020, 129, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, J.L.L.; Pruitt, J.N.; Modlmeier, A.P. Intraspecific Variation in Collective Behaviors Drives Interspecific Contests in Acorn Ants. Behav. Ecol. 2016, 27, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Roches, S.; Post, D.M.; Turley, N.E.; Bailey, J.K.; Hendry, A.P.; Kinnison, M.T.; Schweitzer, J.A.; Palkovacs, E.P. The Ecological Importance of Intraspecific Variation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 2, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, C.L.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J.; Weiser, M.D.; Photakis, M.; Bishop, T.R.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Arnan, X.; Baccaro, F.; Brandão, C.R.F.; et al. GlobalAnts: A New Database on the Geography of Ant Traits (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insect Conserv. Divers. 2017, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudard, C.A.; Robertson, M.P.; Bishop, T.R. Low Levels of Intraspecific Trait Variation in a Keystone Invertebrate Group. Oecologia 2019, 190, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolnick, D.I.; Amarasekare, P.; Araújo, M.S.; Bürger, R.; Levine, J.M.; Novak, M.; Rudolf, V.H.W.; Schreiber, S.J.; Urban, M.C.; Vasseur, D.A. Why Intraspecific Trait Variation Matters in Community Ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Liu, S.; Nakamura, A.; Ellwood, M.D.F.; Zhou, S.; Xing, S.; Li, Y.; Wen, D. Intraspecific Functional Traits and Stable Isotope Signatures of Ground-Dwelling Ants across an Elevational Gradient. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 240230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T.; Solan, M.; Godbold, J.A. Intraspecific Variability across Seasons and Geographically Distinct Populations Can Modify Species Contributions to Ecosystems. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerband, A.C.; Funk, J.L.; Barton, K.E. Intraspecific Trait Variation in Plants: A Renewed Focus on Its Role in Ecological Processes. Ann. Bot. 2021, 127, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleszár, G.; Szabó, S.; Kékedi, L.; Löki, V.; Botta-Dukát, Z.; Lukács, B.A. Intraspecific Trait Variability Is Relevant in Assessing Differences in Functional Composition between Native and Alien Aquatic Plant Communities. Hydrobiologia 2024, 851, 5071–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, G.; Innes, J.L.; Seely, B.; Chen, B. ClimateAP: An Application for Dynamic Local Downscaling of Historical and Future Climate Data in Asia Pacific. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2017, 4, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, C. The Ants of China; China Forestry Publishing House Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 1995; ISBN 978-7-5038-1545-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.-H. A Study of the Biodiversity of Formicidae Ants of Xishuangbanna Nature Reserve; Yunnan Science and Technology Publishing House Co., Ltd.: Kunming, China, 2002; ISBN 978-7-5416-1623-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspari, M.; Weiser, M.D. The Size–Grain Hypothesis and Interspecific Scaling in Ants. Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarty, M.; Abbott, K.L.; Lester, P.J. Habitat Complexity Facilitates Coexistence in a Tropical Ant Community. Oecologia 2006, 149, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, H.; Cunningham, S.A. Restoration of Trophic Structure in an Assemblage of Omnivores, Considering a Revegetation Chronosequence. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M.D.; Kaspari, M. Ecological Morphospace of New World Ants. Ecol. Entomol. 2006, 31, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.R.; Brandão, C.R.F.; Silva, R.R.; Brandão, C.R.F.; Silva, R.R.; Brandão, C.R.F. Ecosystem-Wide Morphological Structure of Leaf-Litter Ant Communities along a Tropical Latitudinal Gradient. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N.A. The Food of the Giant Toad, Bufo marinus (L.), in Trinidad and British Guiana with Special Reference to the Ants. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1938, 31, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.95.3) [Computer Software]. 2025. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/faq/how-do-i-cite-jasp/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Anderson, M.J. A Quick Guide to PRIMER. PRIMER-e Learning Hub. PRIMER-e, Auckland, New Zealand. 2024. Available online: https://learninghub.primer-e.com/books/a-quick-guide-to-primer (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Taudiere, A.; Violle, C. Cati: An R Package Using Functional Traits to Detect and Quantify Multi-level Community Assembly Processes. Ecography 2016, 39, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.L.; Tsang, T.P.N.; Lewis, O.T.; Guénard, B. Trait-similarity and Trait-hierarchy Jointly Determine Fine-scale Spatial Associations of Resident and Invasive Ant Species. Ecography 2021, 44, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Pati, P.K.; Khan, M.L.; Khare, P.K. Plant Functional Traits Best Explain Invasive Species’ Performance within a Dynamic Ecosystem—A Review. Trees For. People 2022, 8, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.S.; Gilbert, B.; Levine, J.M. Plant Invasions and the Niche. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiher, E.; Freund, D.; Bunton, T.; Stefanski, A.; Lee, T.; Bentivenga, S. Advances, Challenges and a Developing Synthesis of Ecological Community Assembly Theory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 2403–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violle, C.; Enquist, B.J.; McGill, B.J.; Jiang, L.; Albert, C.H.; Hulshof, C.; Jung, V.; Messier, J. The Return of the Variance: Intraspecific Variability in Community Ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo, A.; Siefert, A. Intraspecific Trait Variation and the Leaf Economics Spectrum across Resource Gradients and Levels of Organization. Ecology 2018, 99, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichstein, J.W.; Dushoff, J.; Levin, S.A.; Pacala, S.W. Intraspecific Variation and Species Coexistence. Am. Nat. 2007, 170, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockoven, A.A.; Wilder, S.M.; Eubanks, M.D. Intraspecific Variation among Social Insect Colonies: Persistent Regional and Colony-Level Differences in Fire Ant Foraging Behavior. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M.; Addesso, K.M.; Archer, R.S.; Valles, S.M.; Baysal-Gurel, F.; Ganter, P.F.; Youssef, N.N.; Oliver, J.B. Worker Size, Geographical Distribution, and Introgressive Hybridization of Invasive Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Tennessee. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, K.D.; Gabler, C.A. Rapid Evolution in Introduced Species, ‘Invasive Traits’ and Recipient Communities: Challenges for Predicting Invasive Potential. Divers. Distrib. 2008, 14, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | Estimate | Std. Error | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species richness | Poisson (Intercept) | 2.203 | 0.176 | 12.507 | <0.001 |

| Sites-SF | −0.037 | 0.192 | −0.192 | 0.847 | |

| Sites-SI | −0.916 | 0.252 | −3.632 | <0.001 | |

| Abundance | Poisson (Intercept) | 4.523 | 0.190 | 23.833 | <0.001 |

| Sites-SF | 0.243 | 0.056 | 4.345 | <0.001 | |

| Sites-SI | 0.385 | 0.054 | 7.093 | <0.001 | |

| Species richness_local ants | Poisson (Intercept) | 2.084 | 0.192 | 10.83 | <0.001 |

| Sites-SF | 0.078 | 0.198 | 0.396 | 0.692 | |

| Sites-SI | −1.119 | 0.288 | −3.887 | <0.001 | |

| Abundance_local ants | nbinom2 (Intercept) | 3.937 | 0.240 | 16.437 | <0.001 |

| Sites-SF | 0.800 | 0.112 | 7.143 | <0.001 | |

| Sites-SI | −1.377 | 0.155 | −8.886 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Beyond Species Averages: Intraspecific Trait Variation Reveals Functional Convergence Under Invasion. Insects 2025, 16, 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111094

Lu Z, Wang X, Zhang X, Chen Y. Beyond Species Averages: Intraspecific Trait Variation Reveals Functional Convergence Under Invasion. Insects. 2025; 16(11):1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111094

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Zhixing, Xinyu Wang, Xiang Zhang, and Youqing Chen. 2025. "Beyond Species Averages: Intraspecific Trait Variation Reveals Functional Convergence Under Invasion" Insects 16, no. 11: 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111094

APA StyleLu, Z., Wang, X., Zhang, X., & Chen, Y. (2025). Beyond Species Averages: Intraspecific Trait Variation Reveals Functional Convergence Under Invasion. Insects, 16(11), 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111094