1. Introduction

Omnivores can be classified according to their diet or their role in ecological food webs [

1]. Omnivory may be opportunistic, obligatory or facultative, based on the relative importance of plant and prey materials in the insect’s diet. However, according to their ecological role in food webs, an omnivore that feeds on more than one trophic level is commonly termed a “trophic omnivore” [

1]. Intraguild predation is an example of trophic omnivory in which a predator consumes other predators with whom it shares a common herbivore prey [

1,

2]. “True omnivory”, therefore, is a particular case of trophic omnivory in which the consumer feeds on both plants and prey [

1]. According to Hurd [

3], generalist arthropod predators are typically bitrophic: they simultaneously occupy the third and fourth trophic levels by virtue of feeding both on herbivores and each other, i.e., they engage in intraguild predation (IGP).

At the same time, predation can be either between species or among individuals within the same species, since most generalist predators are cannibals [

3]. Cannibalism occurs very frequently in nature and has been documented in more than 1300 species [

4,

5]. For many arthropods, cannibalism is a normal phenomenon, not an anomaly. Cannibalism has been documented in many insect orders, including Odonata, Orthoptera, Thysanoptera, Hemiptera, Trichoptera, Lepidoptera, Diptera, Neuroptera, Coleoptera and Hymenoptera. It occurs among predatory species and herbivores, involving predation by the mobile adults and larvae or nymphs on each other, and on immobile eggs and pupae [

5,

6]. There are many types of cannibalism, e.g., filial cannibalism as an energetic benefit [

7]; sibling cannibalism [

8,

9] and intrauterine cannibalism in parasitoid insects [

10], in which the cannibalism can increase the survival rate when food is scarce [

11]; sexual cannibalism, in which a female insect cannibalizes her male mate during copulation [

12]; cannibalism as competition [

13]; or parasitizing offspring [

5], etc.

In many systems, IGP and cannibalism occur together [

14], and IGP is often associated with cannibalism [

15,

16]. Omnivory can be viewed as a strategy to reduce intraguild predation levels (and cannibalism) as it may allow omnivores to change locations and feed on plants under threat of predation [

1].

From a practical point of view, the effects of IGP and cannibalism in biological pest control have received unequal attention. Many previous studies have been dedicated to the effects of IGP on the efficacy of natural enemies [

17]. Most frequently, IGP is reported to be damaging or antagonistic [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] although it may sometimes have a neutral [

23] or beneficial (synergistic) effect [

24,

25].The effect of cannibalism has received less modelling attention, which is curious since it is often associated with IGP. Moreover, it is an important impediment to efficiency in the mass production of biological control agents [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In addition, in augmentative biological control, releases can result in high densities of natural enemies at low pest levels, or before the pest appears on the crop [

32]. Thus, cannibalism could exert an important influence on biological control outcomes [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Finally, because cannibalism is ubiquitous in food webs and frequent in systems where predator and prey share a common resource (IGP), its impacts on interspecific interactions and community dynamics and structure need to be better understood [

37,

38].

Biological pest control systems are very complex, especially in greenhouse crops where various beneficial organisms may be employed at the same time (predators, parasitoids and entomopathogens) in the same crop cycle to control different phytophagous species [

32]. In such systems, it becomes more important, and sometimes fundamental, to recognize all the ecological relationships because the success of the system may depend on this knowledge [

25]. Information is limited on the effects of cannibalism regarding the efficacy of biological pest control in these systems when, for example, high densities of natural enemies are released in augmentative biological programs [

39] or when the pest population is not present, or present only at a low density. At the same time, agro-ecosystems are usually modified to be simpler than natural ecosystems [

40], involving fewer factors and fewer interactions, which could facilitate the interpretation of ecological relationships.

Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter) (Hem.: Miridae), an omnivorous species [

41], was introduced into Europe [

42,

43] from an originally paleotropical distribution. The species feeds both phytophagously and zoophagously, and has been considered a crop pest [

44,

45]. Its prey range includes aphids, whitefly and eggs and larvae of small lepidopterans [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Conversely,

Nabis pseudoferus Remane (Hem.: Nabidae) can be considered a generalist predator (a non-omnivorous species) [

50]. The majority of the Nabidae studied also practice plant feeding but they are not able to develop in the absence of prey [

51,

52,

53]. Plant feedings are believed to be for the purpose of water acquisition [

54] and do little or no damage to the plant. This practice seems to help the predator to survive during prey scarcity [

53].

N. tenuis is currently used as a biological control agent in tomato greenhouses to control the whitefly

Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hem.: Aleyrodidae) and the tomato leaf miner

Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lep.: Gelechiidae) [

32,

39].

The other species,

N. pseudoferus (Hem.: Nabidae), has a wide prey range and is considered to be an important predator of aphids [

55,

56], but also a voracious predator of lepidopterans and other groups of arthropods, including hemipterans and spider mites [

57,

58,

59,

60].

N. pseudoferus is also currently used as a biological pest control agent of lepidopterans in greenhouses crops [

16,

32].

According to the above and the types of omnivory mentioned above, N. tenuis is a “true omnivore” and N. pseudoferus is a “generalist predator”.

The aim of this work was to study the importance of cannibalism in two species of predatory bugs with different feeding behavior that are often used in biological control programs. The cannibalism performed by each species was studied, both in the presence and absence of prey, in relation to their ontogeny under laboratory conditions, after which the IGP between both species was assayed under similar conditions. Cannibalism by the generalist predator was also studied under microcosm conditions.

4. Discussion

The predatory species

N. pseudoferus, which feeds on food sources from more than one trophic level, may be considered “trophic omnivorous”, according to Coll and Guershon [

1]. It is considered a generalist predator; however, with regard to the diversity of taxonomical groups attacked, it is more specialist than other generalist predators, for instance, spiders, which are able to feed on several trophic levels [

50].

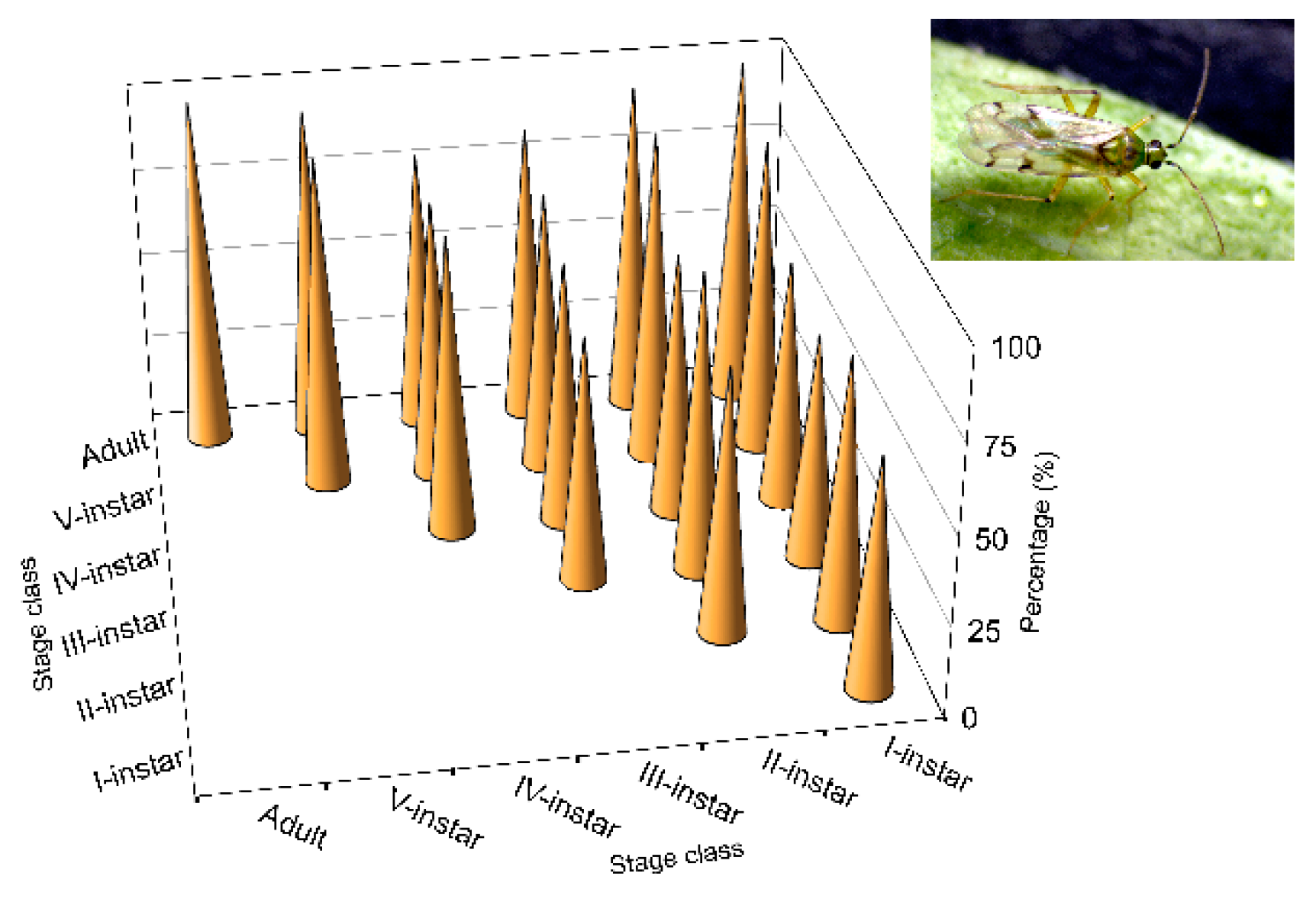

N. pseudoferus was strongly cannibalistic when prey was absent. Individuals in the later developmental stages performed more acts of cannibalism, especially adult females. The results are within the general rule for cannibalism [

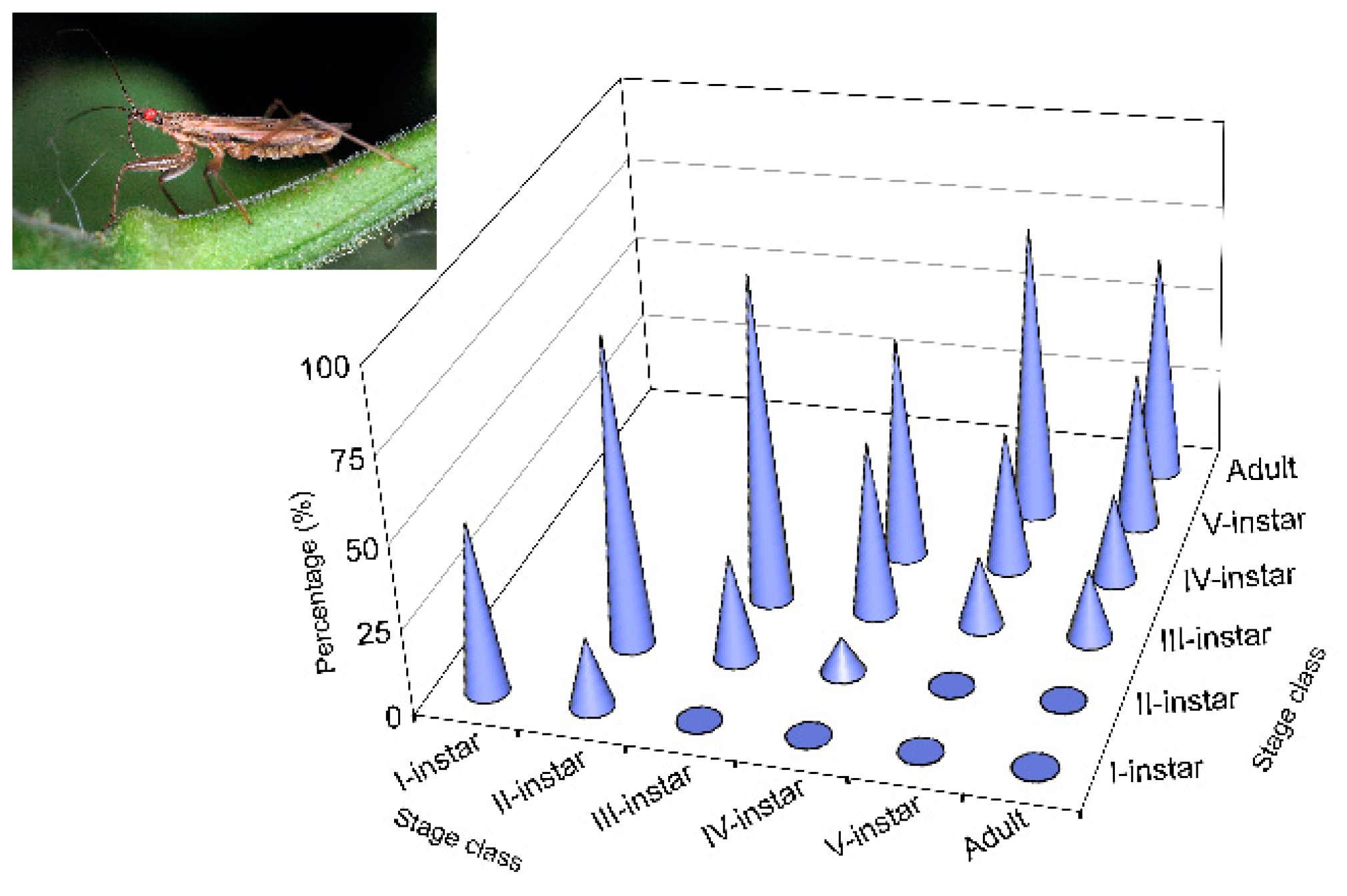

5]. In contrast, the cannibalism rate for the omnivorous species

N. tenuis was substantially lower; this is a “true omnivore”, following the terminology of Coll and Guershon [

1], a particular case of trophic omnivory in which the consumer feeds on both plants and prey. For this species, the same nymphal instars (I, II and, to a lesser extent, III) were cannibalized by conspecifics of the same developmental stage (sibling cannibalism) (

Figure 3 and

Table A4). All of this serves to differentiate the two species. It also means that cannibalism in

N. tenuis is an exception to the general rule of cannibalism, in which the largest (and older) individuals commit more acts of cannibalism than the smaller (and younger) individuals. This is similar to other exceptions cited in other species, such as certain species of fish, dragonfly larvae and parasitoid larvae that are more cannibalistic when smaller (younger) [

5].

There are few studies published studies on cannibalism in

Nabis species, with the exception of the studies performed on the American species

N. alternatus Parshley [

75,

76], as well as on the European species

Himacerus apterus F. [

77]. The observed results regarding the incidence of cannibalism in

N. pseudoferus are larger than those cited for

N. alternatus.

On the other hand, the cannibalism rate for

N. pseudoferus in the absence of prey is comparable to those cited in spiderlings of several wolf spider species [

4,

78,

79]. However, in other species of this spider group, the cannibalism rate is lower [

80,

81].

In relation to other arthropod groups, the values found for

N. pseudoferus were similar to those cited for larvae preyed upon by adult females in some species of predatory mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae) [

62].

Cannibalism in

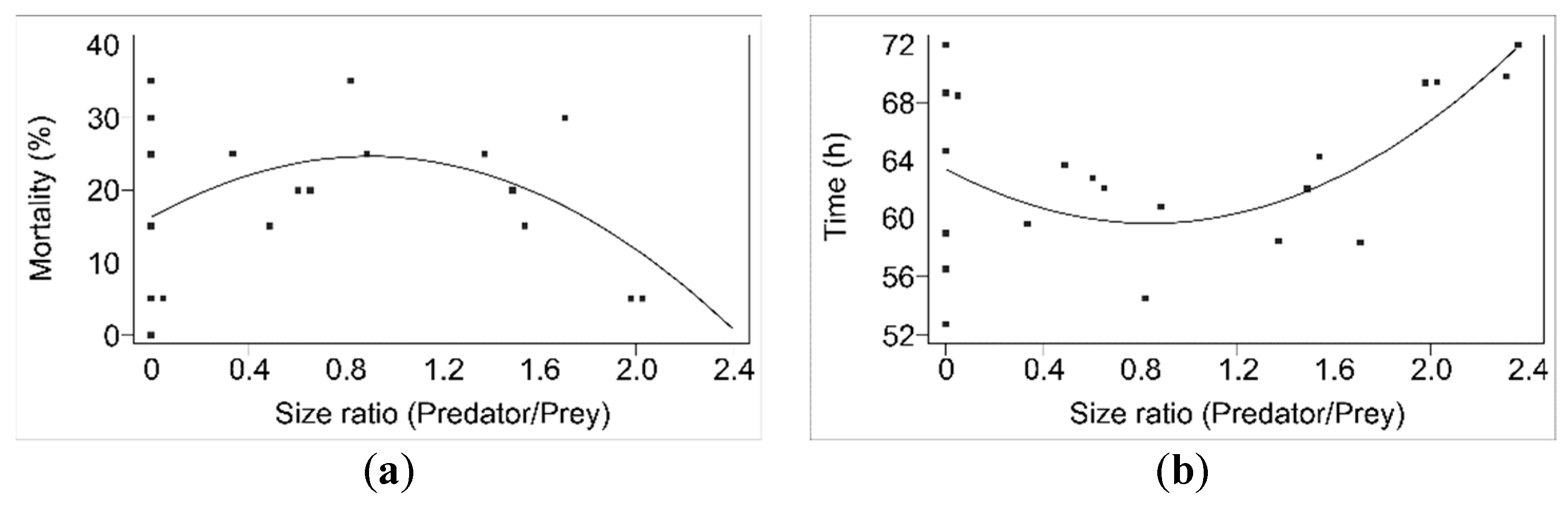

N. pseudoferus, as commented on before, is very important and seems to be closely related to the absence of prey, as well as to size differences between the victim and the predator, as can be observed in the mortality percentages (

Figure A1a) and survival times for the different developmental stages studied (

Figure A1b). The importance of size differences in cannibalism has been cited and widely documented for scorpions [

5,

82], spiders [

8,

79,

82,

83] and predatory coccinellids [

84,

85], as well as for other invertebrate and vertebrate species [

86,

87]; however, it has seldom been studied in insects, with the exception of the work by Laycock et al. [

88].

Analyzing the importance of size differences in

N. pseudoferus cannibalism in more detail, for some species (e.g., fish or wolf spiders), it was reported that there is a predator–prey size difference threshold at which cannibalism takes place [

5,

83]; this does not seems to be the case in

N. pseudoferus. However, only the papers by Polis [

5,

86] have studied size and cannibalism in detail. Polis [

86] found that the relationship between size (size ratio: larger/smaller) and cannibalism was linear in desert scorpions. However, for

N. pseudoferus, the relationship between size and cannibalism, whether the mortality percentage or the survival time, are not linear. The differences could be due, at least in part, to differences in development and life-cycle duration, as in the scorpion species studied, e.g.,

Paruroctonus mesaensis (Stahnke), which has a life cycle > 60 months compared to the short developmental period of

N. pseudoferus (30 days; unpublished data), and in part due to different predation behavior.

A nonlinear relationship between the mortality, or the survival time, and the size ratio was found in

N. pseudoferus (

Figure A1a,b), which seems to be because of two effects: size differences and developmental stages, given that size differences are fundamental for cannibalism to occur. However, cannibalism is also influenced by the developmental stage of the predator, as can be observed from the survival percentages and survival times (

Figure A1a,b). Therefore, cannibalism varies with the different developmental stages of

N. pseudoferus, as measured in the survival percentage and the survival time.

The cannibalism results for

N. tenuis show very low rates in the absence of prey or other food sources (e.g., plants), and in the absence of water. These results accord with those of Moreno-Ripoll et al. [

89] for I- and II-instars of the same species in the absence of prey, although these authors reported different cannibalism results for adult females. In our work, there was no case of cannibalism between adult females whereas these authors did cite adult female cannibalism. The differences could be explained by the higher densities of female used by these authors. A higher density increases the number of encounters, and thus more cannibalism occurs [

5,

82]. Additionally, the survival values for

N. tenuis in the presence of conspecifics are similar to those found in

Macrolophus pygmaeus Wagner (Hem.: Miridae) [

90].

Higher values of

N. tenuis cannibalism for were observed (

Figure 3) in the first three nymphal instars, performed by conspecifics at the same stages, as mentioned above. It should be noted that these

N. tenuis nymphal instars have a higher degree of phytophagy. Thus, the I-instars of the species are able to survive until they become III-instars by feeding only on plant material [

91,

92,

93]. In contrast to the III-instars, the species shows greater zoophagy [

91]; this is contrary to the results that showed reduced cannibalism at that stage and at subsequent stages. Perhaps in the first three instars, cannibalism is not caused by the need to eliminate potential competitors, as cited for other species [

4,

5,

14,

85,

94].

The results showing low levels of cannibalism in omnivorous

N. tenuis suggest that omnivores sustain themselves on plant sources in the absence of prey without the need to resort to cannibalism, as stated by Leon-Beck and Coll [

95]. Moreover, their potential as a phytophagous species, as observed in our results, is opposite to that reported by Bernays [

96] for cannibalism in phytophagous insects, suggesting that in this group of insects, cannibalism is more common among generalist than specialist herbivores.

For

N. tenuis, despite finding weak cannibalism, we also established a nonlinear relationship between the mortality percentage or survival time, and the size differences between the predator and the victim (

Figure A2a,b); this contrasts with

N. pseudoferus, where we found cannibalism differences occurring at low to intermediate sizes. This would suggest that cannibalism is more influenced by behavior, mainly of the early instars, than the size differences of the conspecifics.

In this work, the differences between

N. pseudoferus and

N. tenuis in the cannibalism rate and the attack stage, when both species share the same ecological niche [

97], could be due to their different diets:

N. pseudoferus is a “non-omnivorous predator” and

N. tenuis is a “true omnivore”. Thus, in the absence of prey,

N. pseudoferus cannot opt for any other food source than cannibalism whereas under the same circumstances,

N. tenuis can choose to feed phytophagously. In contrast, omnivory could be a strategy to reduce IGP levels (and cannibalism) as it allows omnivores to change their location and to feed on plants in the presence of other predators [

1].

From the IGP trial results,

N. pseudoferus acts as an IG predator and kills

N. tenuis as IG prey (

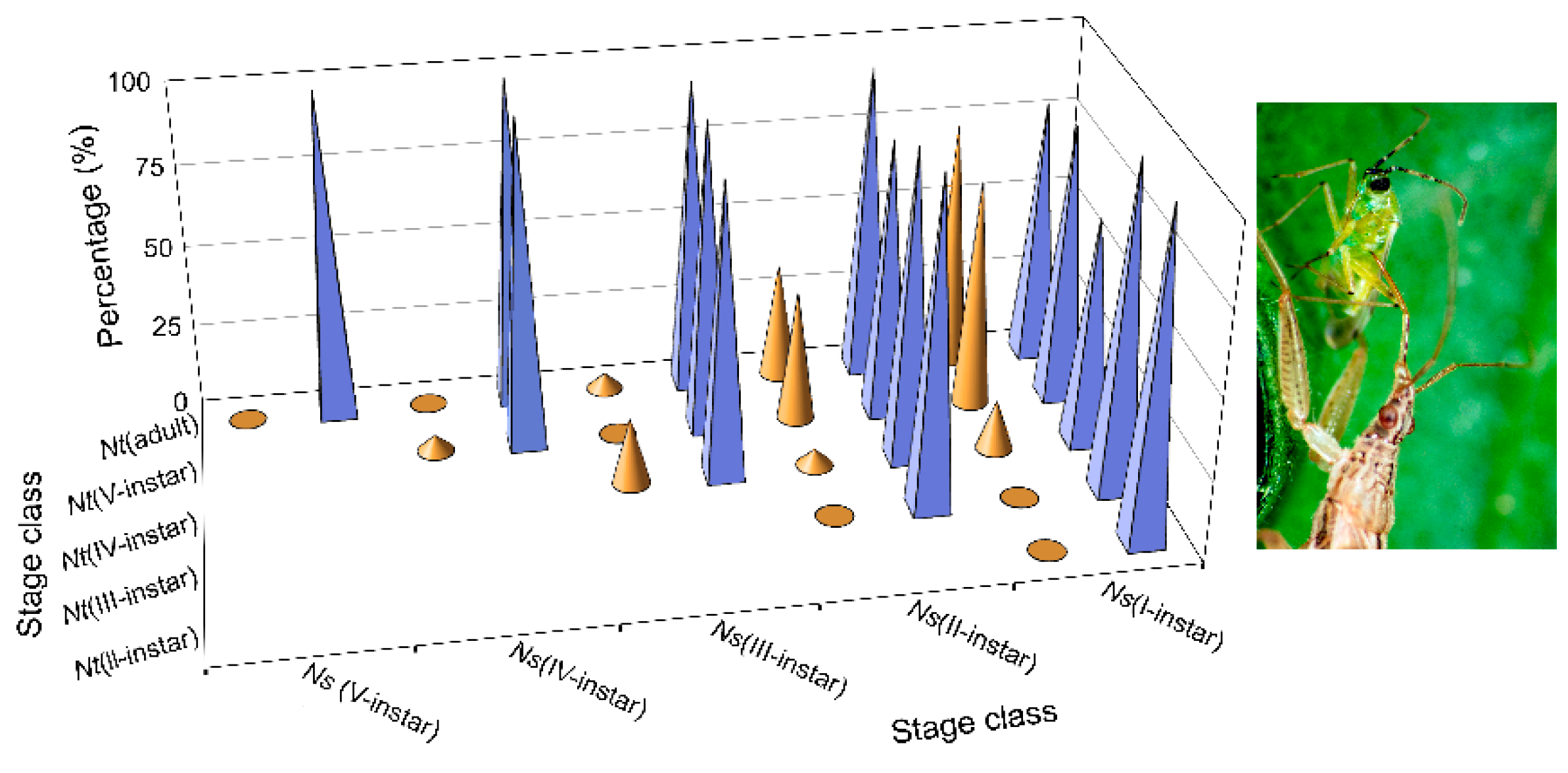

Figure 4). It is an asymmetrical relationship in favor of the former species, depending on the size differences between the species (

Figure 1). This confirms the work of Polis et al. [

14], which states that relative body size and the degree of trophic specialization are the two most important factors influencing IGP frequency and direction. Most IGP occurs in systems with size-structured populations and is carried out by generalist predators who are usually larger than their intraguild prey. Many of these IG predators also cannibalize smaller conspecifics.

By studying

N. tenuis predation at different developmental stages by

N. pseudoferus in the two IGP tests performed, we can observe that both the survival percentage and the survival time are strongly influenced by size differences between the predator and prey (

Figure A3a,b;

Table A6 and

Table A7)—this is known to happen in cannibalism, and has been shown, not only in our results, but also in numerous other studies [

5,

14,

76,

98,

99].

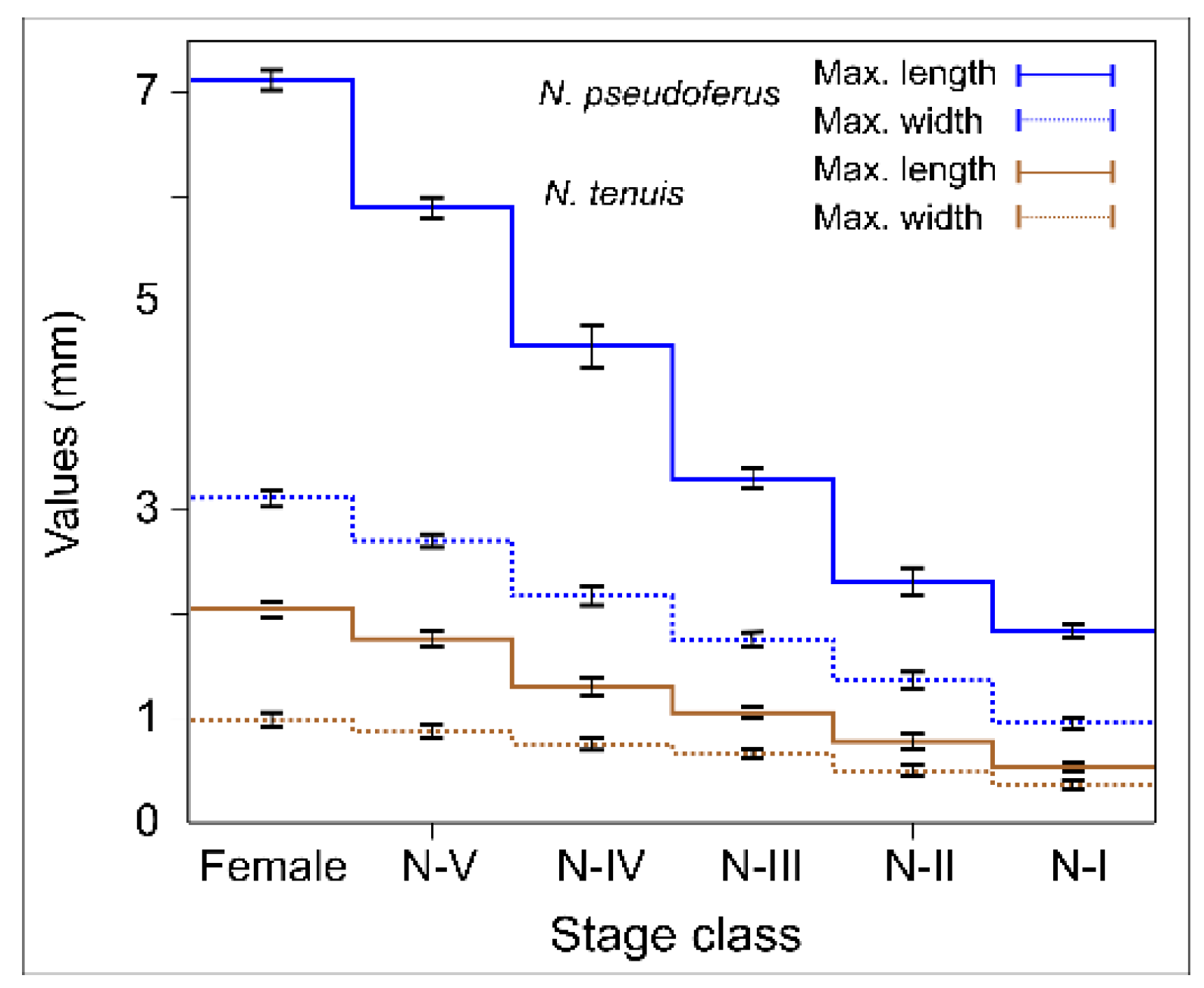

However, in the present study, we found exceptions to the above relationship of size and IGP. In general, the different

N. tenuis developmental states are smaller in size than those of

N. pseudoferus, except for the adult stage of the

N. tenuis, which is very similar to the III-instar state of

N. pseudoferus (and larger than the I- and II-instars), whereas the V-instars of

N. tenuis are larger than the I- and II-instars of

N. pseudoferus (

Figure 1). Despite these size differences, similar survival percentages and survival times were observed for

N. tenuis adult females paired with I-instars of

N. pseudoferus (

Figure 3 and

Table A7). In the other cases where there was an equal or smaller size,

N. pseudoferus predated

N. tenuis. This may be motivated (in the absence of molting individuals) by the fact that, for smaller or same-sized individuals,

N. pseudoferus exhibits better-suited predatory behavior for capturing and killing than does

N. tenuis. We know that

Nabis species inject venom into their prey [

100,

101] and/or have better morphological adaptations (raptorial forelegs) [

102] (

Figure 2), characteristics that are not present in the other species. Such behavior in predatory

Nabis species was observed when they were attacking larger, phytophagous species (e.g.,

Spodoptera exigua (Hübner), Lep.: Noctuidae) [

103].

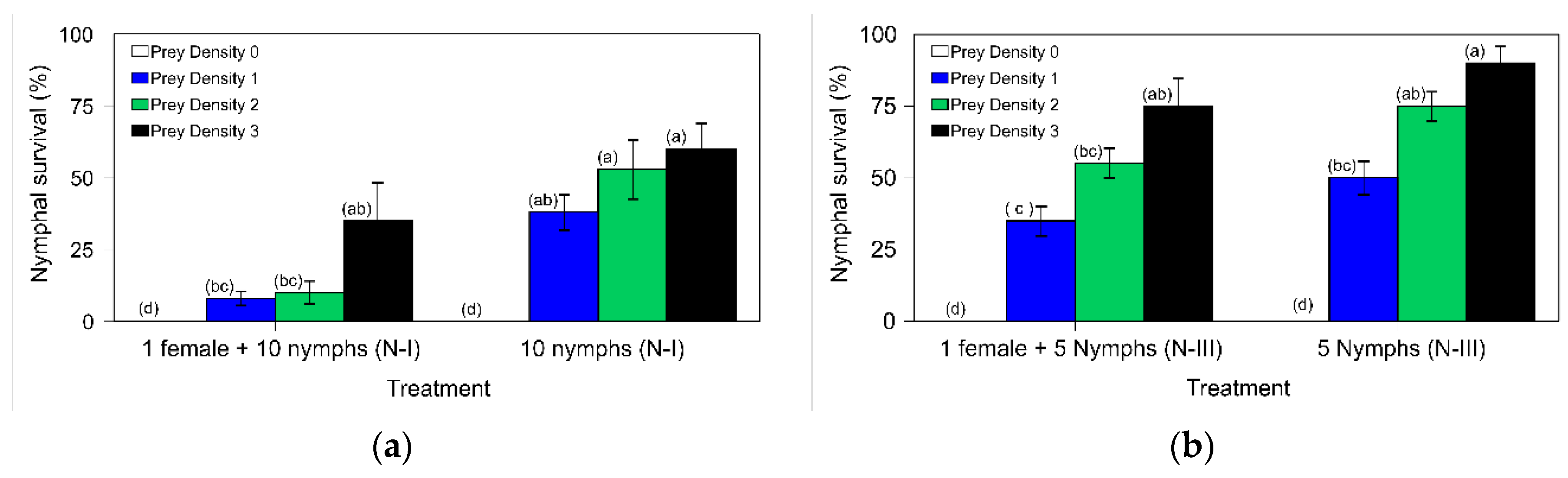

The importance of the presence of prey and refuge (the plant) in the

N. pseudoferus cannibalism has been underscored in both microcosm assays (

Figure 5a,b). This had already been cited in numerous studies on the presence and density of prey [

9,

34,

84] and refuge [

4,

19]. However, in such circumstances, the filial cannibalism level of

N. pseudoferus is still very high, especially by adult females on the first instars (I- to III-instars) (

Figure 5a), more so than on the later stages (III to V-instars) (

Figure 5b). This could explain the location of individuals within the plant. In the absence of other predatory species, the females lay eggs mostly into the leaf petioles spread out equally over the height of the plant [

104]. Moreover,

Nabis adults prefer to sit on the top or slightly lower in the plant canopy, while immature individuals are found lower down in the plant [

71,

72].

Insects and other arthropods, unlike vertebrate species, have complex life cycles in which the successive stages may differ more dramatically, both in physical appearance and in their ecological role [

105,

106,

107,

108]. The findings from the two species studied indicate that cannibalism depends not only on the species, but also on their stage structure. Most ecological models in contemporary ecological theory ignore the implications of the age and size variation, particularly within populations. This is also true for empirical studies, both experimental and non-experimental [

38]. However, recent studies show that stage structure can modify the dynamics of consumer–resource communities owing to stage-related shifts in the nature and strength of the interactions that occur within and between populations [

108]. Consequently, these results can help to develop mathematical models based on stage structure, by considering a more realistic species ontogeny. Furthermore, and from the applied standpoint, the results of this study also highlight the importance of cannibalism, and its repercussions, in current biological control systems.