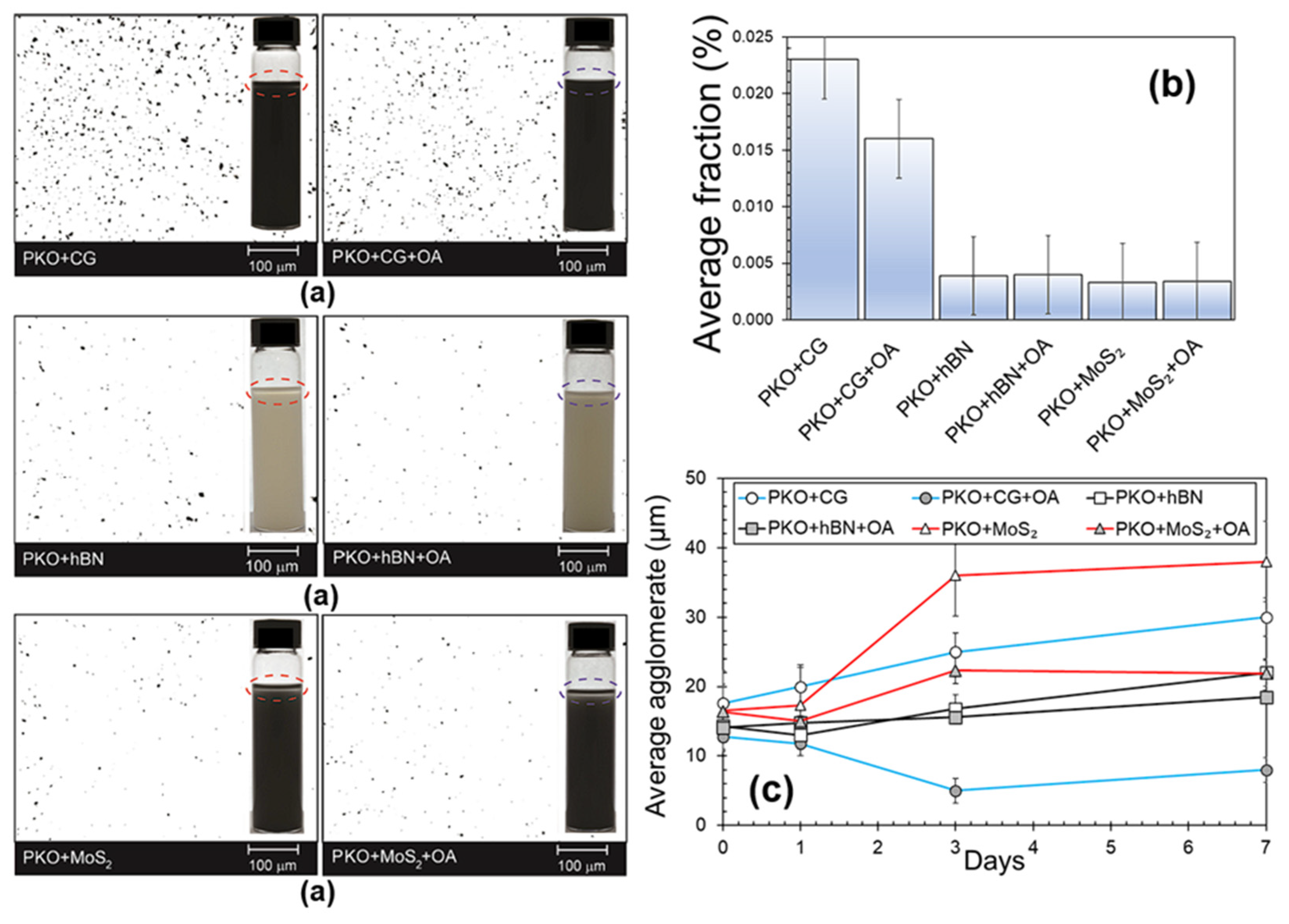

3.1. Effect of Oleic Acid Surfactant on Dispersion Stability

Optical microscopy findings for nanolubricants including PKO with 0.05 wt% CG, 0.05 wt% hBN, and 0.05 wt% MoS

2 are shown in

Figure 4, both with and without oleic acid (OA) used as a surfactant. Incorporating OA greatly improved the dispersion of CG nanoparticles and decreased their aggregation size. Quantitative examination of the images showed that the proportion of the area occupied by CG agglomerates decreased by 30.4% when OA was added, indicating better dispersion stability. In line with these findings,

Figure 4a shows that the PKO + CG + OA formulation was more stable in dispersion than PKO + CG alone. The agglomeration size significantly decreased from 17.61 μm to 12.23 μm after adding OA to the CG-based nanolubricant, as shown in

Figure 4b. The PKO + CG + OA formulation showed better uniformity than the OA-free one, which had more polydispersity and bigger agglomeration dimensions, as shown by the smaller error margin. The agglomeration size in the PKO + CG + OA nanolubricant fell somewhat to 11.2 μm after 1 day of storage, based on subsequent research, while it increased significantly to 19.98 μm in the PKO + CG sample that did not include OA. This pattern verifies that the surfactant successfully stabilises the suspension of CG nanoparticles for a short period of time. The PKO + CG + OA formulation showed signs of instability after 3 days, as the agglomeration size increased significantly.

The addition of OA also helps to disperse hBN nanoparticles more evenly. Agglomerate size was likely reduced since the area percentage of hBN agglomerates was down from 0.0039% to 0.0038%. The visual pictures in

Figure 4a further verify the higher colloidal stability, which is confirmed by the better dispersion and decreased particle clustering in the PKO + hBN + OA nanolubricant. Only a small decrease in agglomeration size, from 14.34 μm to 14.12 μm, was likewise caused by the addition of OA. Additionally, the particle sizes of the PKO + hBN + OA sample remained mostly unchanged after 3 days, growing marginally to 14.42 μm, in contrast to the more noticeable changes shown in

Figure 4c for the OA-free form. After 7 days, the agglomeration size was still less in the OA-containing sample compared to the one without OA, even though it had risen.

On the other hand, when comparing the PKO + MoS

2 + OA sample to its OA-free counterpart, the optical micrograph in

Figure 4b reveals little improvement in particle dispersion. Surprisingly, after adding OA, the fraction of area occupied by MoS

2 agglomerates rose from 0.0033% to 0.0034%. This small increase might be due the sedimentation rate being lower than usual, maybe because there are more suspended particles in the solution between the glass slides. It would seem that these results contradict the optical observations in

Figure 4a, which indicated a significant improvement in stability. The disparity suggests that there may not have been enough OA adsorbed onto the MoS

2 surface to considerably reduce agglomeration. Thus, OA may temporarily reduce agglomeration but have no impact on the dispersion stability of MoS

2 nanolubricants in the long run.

In order to verify these theories, CG, hBN, and MoS2 nanoparticles in suspension were subjected to dynamic light scattering (DLS) to see how OA affected their aggregation behaviour. The first agglomeration diameters of the PKO + MoS

2 and PKO + MoS

2 + OA nanolubricants were 16.45 μm and 16.40 μm, respectively, and there was no significant difference between the two, as shown in

Figure 4c. The agglomeration size in the PKO + MoS

2 formulation grew after 1 day, but in the PKO + MoS

2 + OA sample it shrank somewhat. Both formulations seem to have low colloidal stability, according to these opposing tendencies. A slight stabilising impact was shown by the fact that the agglomeration size in the OA-containing sample remained lower than that in the OA-free sample from 1 to 7 days.

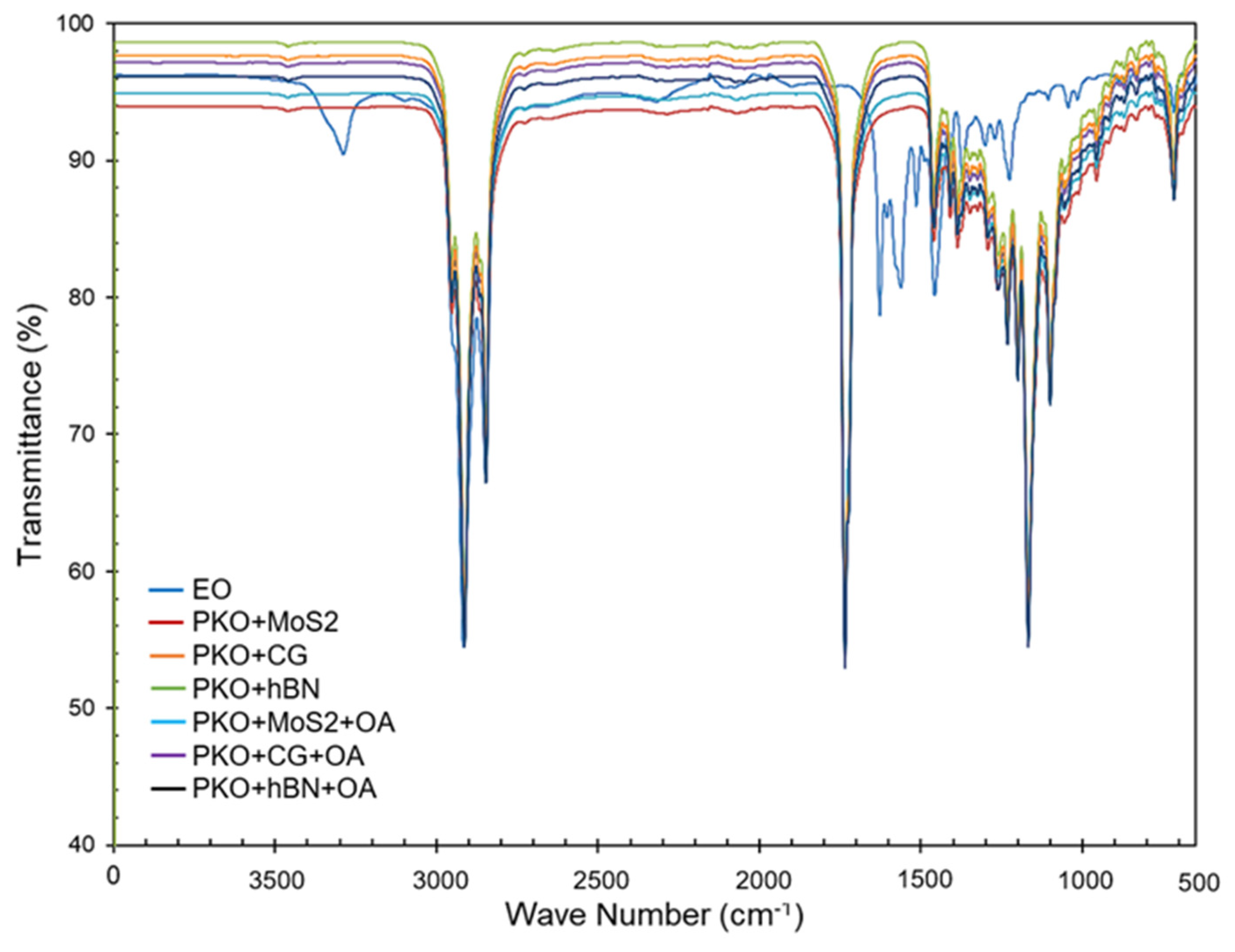

3.2. FTIR Analysis

Figure 5 shows that the FTIR spectra of the base fluids (engine oil) are dominated by the characteristic functional groups of long-chain hydrocarbons. Strong CH

2 asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations are observed at 2958 and 2850 cm

−1, while the ester carbonyl band at ~1740 cm

−1 is sharp and intense, confirming the ester backbone of palm kernel oil. Additional bands at 1465 and 1377 cm

−1 correspond to CH

2/CH

3 bending, with further C–O and C–O–C stretching features in the 1250 to 1000 cm

−1 region, and the CH

2 rocking band at ~720 cm

−1. These assignments indicate that the chemical structure of the oils remains intact throughout the formulation process, with no evidence of hydrolysis, oxidation, or transesterification under the studied conditions.

For samples containing nanoparticles alone (MoS2, carbon/graphite, and hBN), the main PKO bands are preserved without significant shifts, confirming that no new covalent chemical species are formed. The observed changes are limited to small peak broadening, minor intensity variations, and slight baseline distortions, which can be attributed to physical adsorption of oil molecules on nanoparticle surfaces and light scattering effects. A weak perturbation around ~1360 cm−1 is observed in the PKO + hBN sample, which may reflect a B–N contribution. The spectra suggest that, in the absence of dispersant, the nanoparticles remain physically dispersed, with only weak interfacial interactions with the oil matrix.

The inclusion of oleic acid (OA) as a surfactant introduces distinct and consistent spectral modifications. All OA-containing samples display broadening of the ester carbonyl region with a new shoulder near 1710 to 1725 cm

−1, together with an enhanced broad absorption in the 3500 to 2500 cm

−1 region. These changes are characteristic of hydrogen-bonded carboxylic acids and indicate that OA successfully adsorbs onto nanoparticle surfaces while interacting with the oil matrix through its hydrophobic tail. This adsorption process reflects the role of OA in stabilizing the dispersion of nanoparticles, which was particularly evident in the PKO + hBN + OA formulation, where the most pronounced carbonyl broadening was detected. Therefore, the FTIR analysis confirms that, while the base oil structure remains stable, OA functions effectively as a dispersant by anchoring nanoparticles via its polar carboxyl head and providing steric stabilization through its hydrocarbon chain. The summarised results are shown in

Table 3.

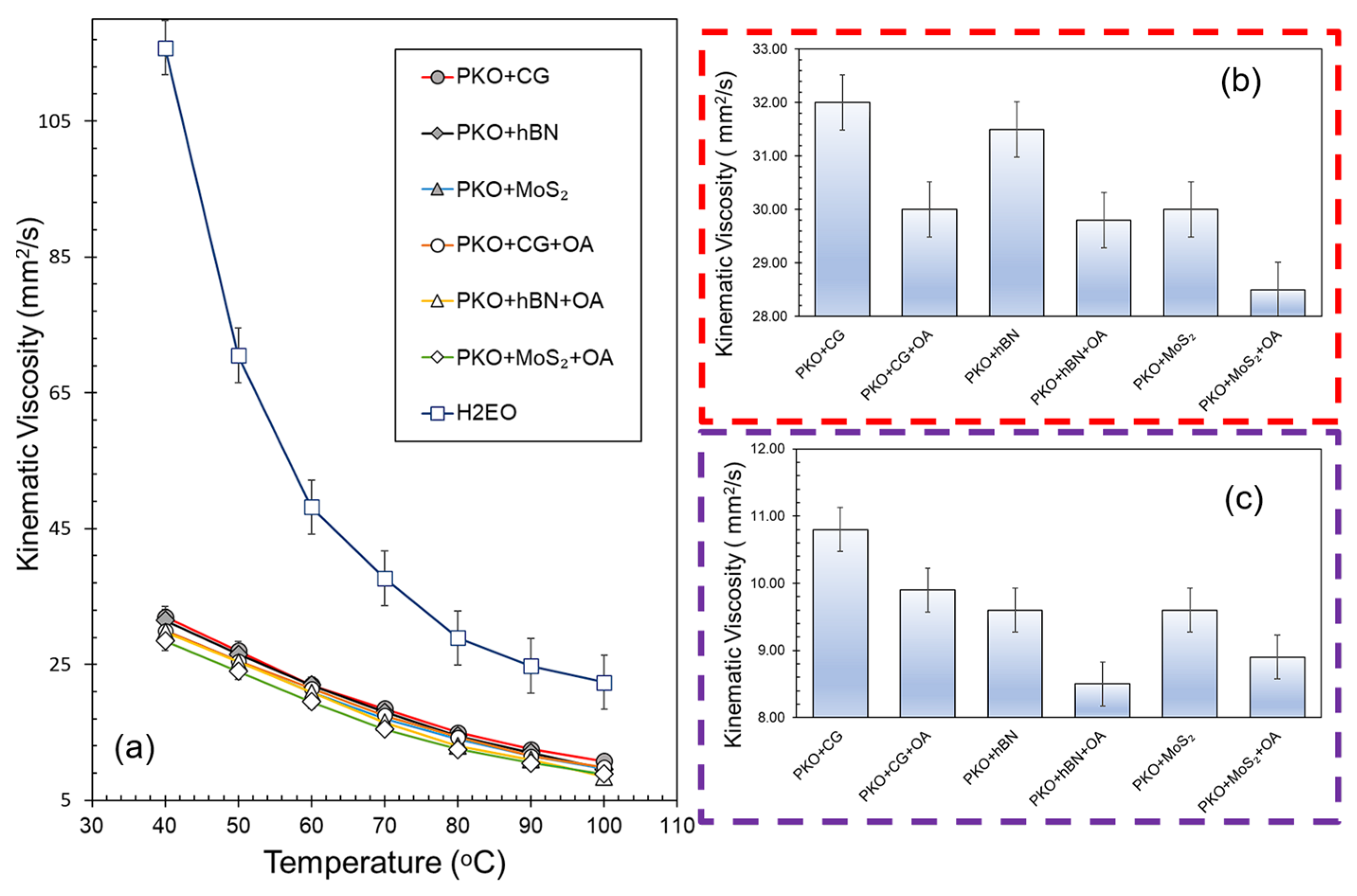

3.3. Analysis on Kinematic Viscosity

The kinematic viscosity profiles of PKO-based nanolubricants with various nanoparticles (CG, hBN, and MoS

2) and the influence of oleic acid (OA) as a surfactant are shown in

Figure 6. From 40 to 100 °C, all PKO-based nanolubricants showed decreasing viscosity with temperature. Compared to the H2EO reference oil, PKO-based nanolubricants displayed significantly lower viscosities, reflecting PKO’s inherently lower molecular weight triglyceride composition. The narrow separation between viscosity curves for the PKO nanolubricants indicates that the 0.05 wt% nanoparticle loading only modestly influences bulk rheology at elevated temperatures. The calculated viscosity index (VI) values for the nanolubricants ranged from 175 to 188, which are considerably higher than that of H2EO (VI ≈ 152), suggesting superior viscosity temperature stability and greater potential for maintaining lubricating film thickness over a range of operating conditions.

At 40 °C (

Figure 6b), the PKO + CG and PKO + hBN samples without OA exhibited the highest viscosities (32.05 mm

2 s

−1 and 31.87 mm

2 s

−1, respectively), suggesting that nanoparticle agglomeration may have increased hydrodynamic drag in the oil matrix [

21]. This finding is consistent with the optical microscopy results (

Figure 6a), where larger agglomerates were observed in the OA-free formulations. Upon OA incorporation, the viscosities for PKO + CG and PKO + hBN decreased to 30.85 mm

2 s

−1 and 29.65 mm

2 s

−1, respectively, reflecting improved dispersion stability and reduced particle clustering. The smaller, more uniformly dispersed nanoparticles likely reduced flow resistance.

Alignment with fluid induces streamlining, thereby lowering internal shear stresses [

26]. This is further evidenced by the slight increase in VI for these OA-containing formulations (from ~180 to ~185), indicating that improved nanoparticle dispersion enhanced the oil’s ability to resist viscosity loss with temperature.

At 100 °C, viscosity values decreased for all formulations (8.84–10.94 mm2 s−1), consistent with thermal thinning of the oil. While absolute differences between samples were smaller than at 40 °C, the relative variation between the highest and lowest values was in fact larger (~23% at 100 °C vs. ~12% at 40 °C). This indicates that nanoparticle type and OA addition continued to influence viscosity even at elevated temperatures, although the trends cannot be attributed solely to particle aggregation without further rheological analysis. The lowest viscosities were recorded for PKO + hBN + OA (8.84 mm2 s−1) and PKO + MoS2 + OA (9.12 mm2 s−1), which may reflect the combined effect of thermal thinning and the presence of smaller, well-dispersed particles contributing less to hydrodynamic resistance. Interestingly, MoS2-based nanolubricants showed only marginal VI improvement with OA (from ~176 to ~178), aligning with earlier findings that OA’s stabilisation effect on MoS2 is weaker over extended periods. Overall, these viscosity, temperature, and VI results confirm that OA-enhanced dispersion stability translates into higher VI values and better thermal robustness, particularly for CG and hBN systems, where agglomeration control is most effective.

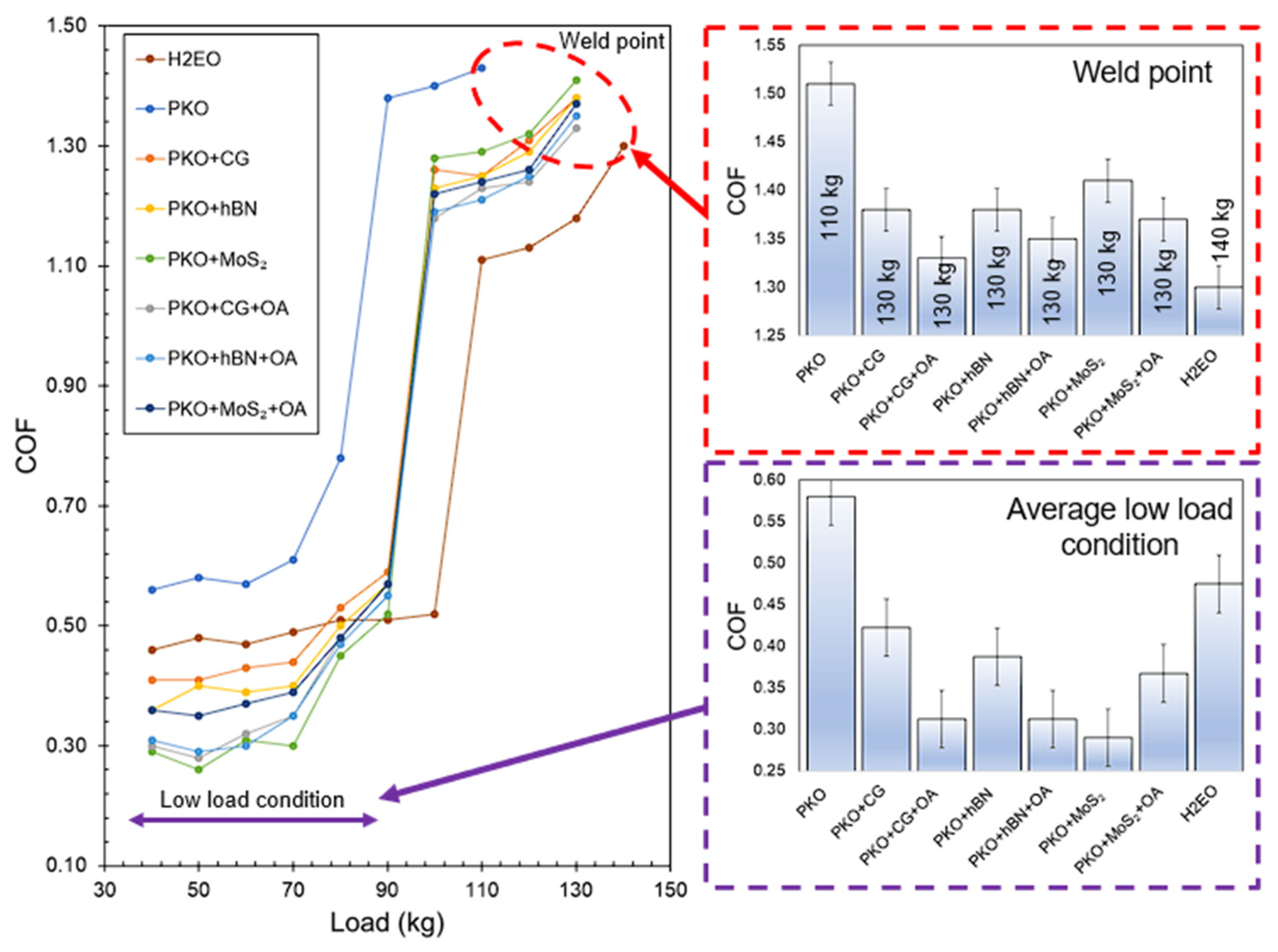

3.4. Analysis of Friction Under Extreme Pressure

The relationship between the coefficient of friction (COF) and the applied load for PKO-based nanolubricants, including CG, hBN, and MoS

2, both with and without oleic acid (OA), is shown in

Figure 7. Under low load conditions (40–90 kg), all formulations including nanoparticles demonstrated a significant decrease in coefficient of friction (COF) compared to pure palm kernel oil (PKO) and H2EO. Pure PKO had the greatest average COF of 0.58, while the incorporation of CG decreased this value to 0.43, reflecting a 25.86% decrease. The use of OA further reduced the COF to 0.28 for PKO + CG + OA, signifying a 51.72% decrease compared to PKO. This large improvement aligns with the optical microscopy and viscosity results, indicating that OA markedly decreased CG agglomeration size by 30.4% and improved dispersion stability, resulting in more uniform nanoparticle distribution in the tribological contact zone. In hBN-based samples, the addition of OA decreased the COF from 0.38 to 0.31, representing an 18.42% reduction, which aligns with the mild but steady enhancement in dispersion seen over a 7-day period. Nanolubricants based on MoS2 had the lowest coefficient of friction (COF) of 0.36 under low load when mixed with oleic acid (OA), indicating a 37.93% decrease compared to palm kernel oil (PKO), despite previous findings suggesting that OA’s long-term stabilisation impact on MoS

2 was limited, whereas nanolubricants based on MoS

2 showed a decline in performance when OA surfactant was added. This finding is in agreement with other research that found lower COF values in MoS

2 nanolubricants without surfactant as compared to those which include OA [

39,

40]. Because of the increased friction, OA may prevent MoS

2 nanoparticles from effectively interacting with the contact surfaces, which would restrict their ability to form a protective tribofilm.

Nanoparticles increased the weld point from 110 kg (PKO) to 130 kg, improving load-bearing capacity by 18.18%. The PKO + CG + OA sample exhibited the lowest coefficient of friction at the weld site (1.28), reflecting an estimated 15.2% decrease relative to PKO, indicating a synergistic effect of OA and CG in forming a robust composite tribofilm under extreme pressure. In the hBN systems, the addition of OA decreased the weld-point coefficient of friction from 1.39 to 1.35 (a 2.88% reduction) and from 1.37 to 1.34 (a 2.19% reduction), respectively, indicating the synergistic effects of enhanced dispersion and diminished boundary resistance, as evidenced by the viscosity index improvement from approximately 180 to approximately 185 for these systems.

Correlation of COF data with dispersion stability reveals that nanolubricants exhibiting superior particle stability generally demonstrate reduced COF, particularly in boundary lubrication conditions at low loads. In the case of hBN, despite a small drop in agglomeration size with OA (from 14.34 to 14.12 μm), the particle distribution exhibited temporal stability, resulting in a consistently low coefficient of friction over the entire load spectrum. Conversely, MoS2 exhibited a small OA-induced decrease in agglomeration size (from 16.45 to 16.40 μm initially) and a moderate enhancement in viscosity index (about 176 to 178), while still gaining tribological advantages, owing to its inherent layered architecture that promotes shear.

PKO + CG + OA showed a reduced COF compared to the other nanolubricant formulations, likely due to differences in lubrication mechanisms under extreme pressure boundary conditions. For PKO + CG + OA, the synergistic interaction between oleic acid (OA) and carbon graphene (CG) is the key factor, where OA improves CG dispersion stability by approximately 30.4% (reduced agglomerate area and smaller mean platelet size), enabling more graphene platelets to enter and remain active in the contact zone [

20]. OA also chemisorbs onto steel surfaces, forming an iron–oleate boundary layer, while CG integrates into this layer to create a lamellar solid–liquid composite tribofilm that can shear easily and patch micro-defects, thereby suppressing severe adhesion. Graphene’s high in-plane thermal conductivity further dissipates localised flash temperatures, reducing the risk of seizure, as explained by [

24]. In contrast, benchmark lubricant benefits from its higher base oil viscosity and strong polar ester boundary film formation, which more effectively maintains a stable fluid film at the weld point. While PKO + CG + OA shows slightly higher COF because its mechanism relies more on boundary and solid lubrication rather than continuous thick-film separation, the difference is minimal, and its improved viscosity index still supports consistent film formation at high loads. This demonstrates that optimised additive chemistry in PKO + CG + OA can achieve friction performance comparable to that of the benchmark oil, despite relying on a lower-viscosity base fluid.

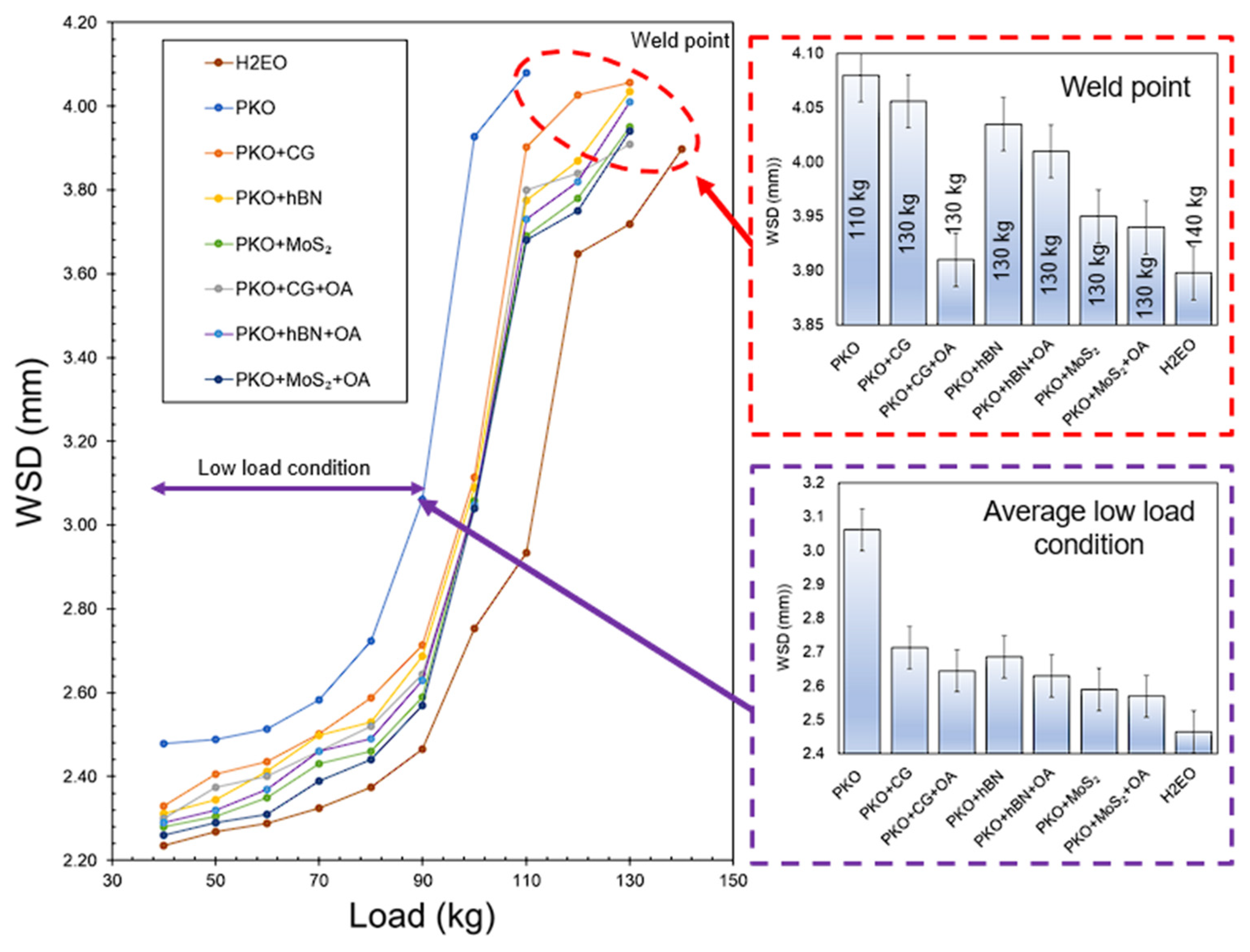

3.5. Analysis of Wear Scar Diameter

Figure 8 illustrates the progression of wear scar diameter (WSD) in relation to applied load for PKO-based nanolubricants, including CG, hBN, and MoS

2, both with and without oleic acid (OA). Under low load conditions (40–90 kg), all formulations including nanoparticles demonstrated reduced WSD values in comparison to pure PKO. Pure PKO had the highest average low-load WSD at 3.06 mm, whereas the incorporation of CG decreased this reading to 2.71 mm, reflecting a 11.44% decrease. The use of OA further reduced the WSD to 2.65 mm for PKO + CG + OA, indicating a 13.40% drop relative to PKO. These enhancements correspond with previous dispersion stability findings, whereby the inclusion of OA decreased CG agglomeration size by 30.4% and improved uniformity, facilitating CG’s formation of a more constant protective layer in the contact zone, hence mitigating wear propagation.

The average low-load wear scar diameter for hBN-based nanolubricants decreased from 2.69 mm without oleic acid to 2.63 mm with oleic acid, indicating a 2.23% reduction. The decrease, although less significant than that of CG, presumably contributed to consistent wear protection because of the stability enhancement shown by optical microscopy. Nanolubricants based on MoS

2 demonstrated a decrease in wear, exhibiting WSD values of 2.59 mm without OA and 2.57 mm with OA under low load conditions. The moderate OA impact aligns with previous studies indicating that OA offers limited long-term stabilisation for MoS

2; yet, the intrinsic lamellar structure of MoS

2 provides underlying anti-wear properties via straightforward interlayer shear, enhancing lubrication efficacy [

41].

The WSD trends exhibit a high correlation with previously reported COF and viscosity data. Nanolubricants exhibiting enhanced dispersion stability (CG + OA and hBN + OA) showed less friction and wear, especially under mixed lubrication conditions at low loads. The reduced viscosity at 40 °C in samples containing OA likely facilitated lubricant flow into the contact interface, while the higher VI guaranteed superior film thickness preservation at elevated temperatures [

42]. In MoS

2-based lubricants, despite the modest augmentation of OA dispersion, the amalgamation of high load-carrying capacity, low coefficient of friction at the weld site, and minimum wear scar diameter expansion substantiates that the inherent features of nanoparticles may partly mitigate dispersion-related constraints. This substantiates the assertion that particle stability and material properties collaboratively dictate the tribological efficacy of PKO-based nanolubricants.

The performance of PKO + CG + OA at the weld point is similar to that of benchmark lubricant, but the effects on tribological behaviour diverge, offering significant insights into the reasons why PKO + CG + OA attains comparably low WSD values. Both lubricants exhibit strong resistance to severe adhesive failure under extreme pressure, yet PKO + CG + OA’s advantage lies in the synergistic action between CG and OA. CG contributes a lamellar solid lubrication effect, while OA enhances CG’s dispersion stability in PKO and chemisorbs onto steel surfaces to form a load-bearing iron–oleate film [

43]. This dual action creates a uniform and resilient tribofilm that suppresses abrasive and adhesive wear. H2EO, on the other hand, benefits from its inherently higher viscosity and stronger boundary film formation due to its polar ester structure, which helps maintain a stable lubricant layer and delay severe wear onset. However, while H2EO’s high viscosity index ensures consistent film thickness across temperature variations, PKO + CG + OA achieves a similar effect through its improved dispersion stability and composite tribofilm formation, despite having slightly lower viscosity. This explains why PKO + CG + OA and H2EO exhibit similar WSD performance and maintain surface protection effectively, but PKO + CG + OA does so through a synergistic additive mechanism, whereas the benchmark lubricant relies more on bulk fluid film stability. The comparable results highlight that, in extreme pressure regimes, optimised additive interactions can achieve wear mitigation equivalent to that of a high-viscosity base oil [

44].

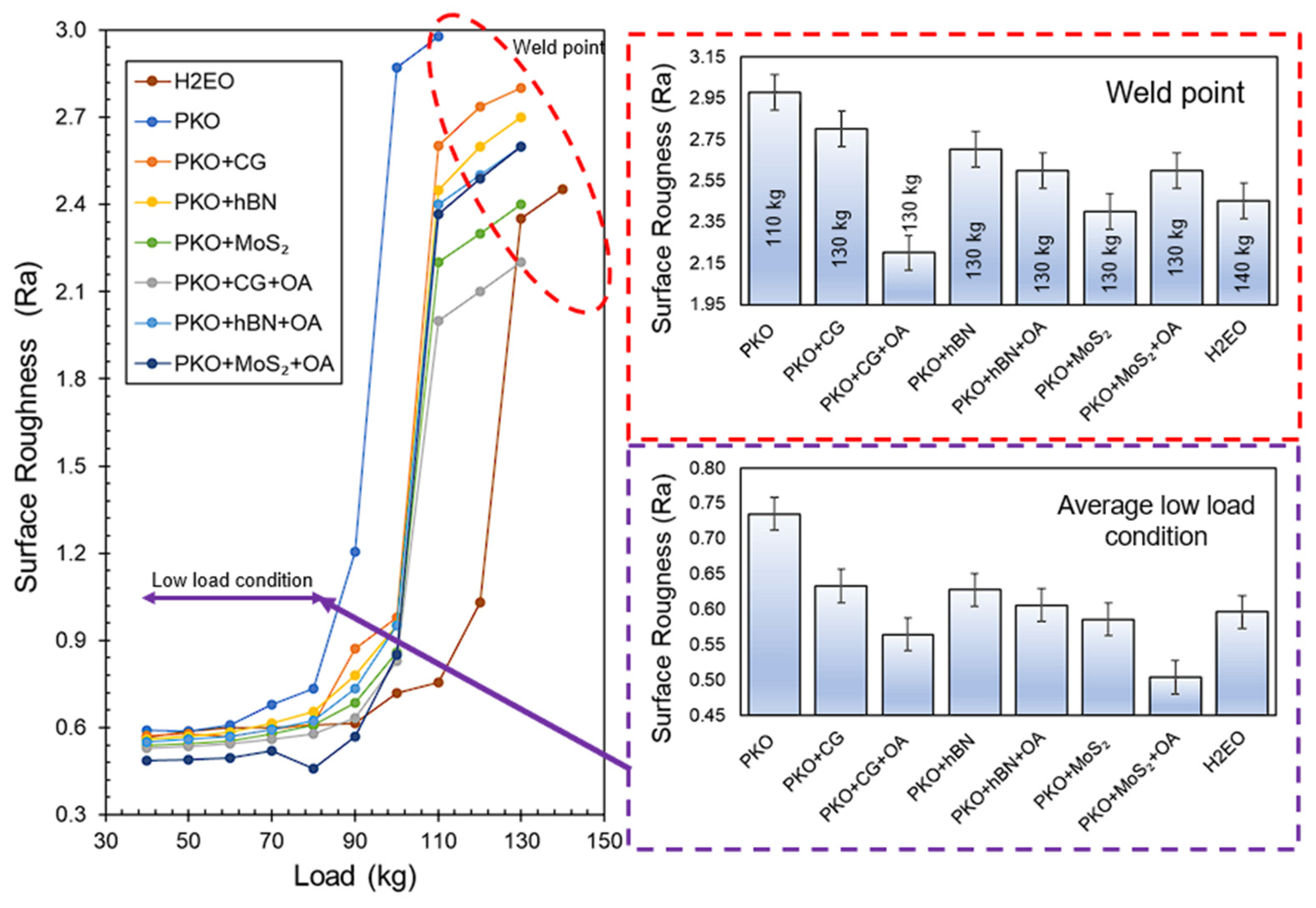

3.6. Analysis of Surface Roughness

Under low load conditions (40–90 kg), the PKO + MoS

2 + OA nanolubricant has the lowest average surface roughness of all tested formulations, surpassing the benchmark lubricant, as seen in

Figure 9. The enhanced surface smoothing results from the synergistic interaction between the intrinsic lamellar crystal structure of MoS

2 and the surfactant characteristics of OA. Dispersion analysis revealed that OA resulted in a small reduction in initial MoS

2 agglomerate size (from 16.45 μm to 16.40 μm) and offered minimal enhancement in long-term stability. However, DLS and optical microscopy findings corroborated that MoS

2 suspensions with OA exhibited marginally smaller agglomerates over time relative to those without OA. This provisional stabilisation facilitated a more uniform distribution of MoS

2 platelets inside the tribological contact zone, hence reducing three-body abrasion.

The polar head of oleic acid chemisorbs onto steel surfaces, creating an iron–oleate boundary coating that reduces asperity–asperity contact, while the nonpolar tail aligns with the lubricating medium to improve wettability [

28]. This mixed solid–liquid tribofilm, when integrated with readily sheared MoS

2 platelets, reduces ploughing and micro-cutting, resulting in smoother worn surfaces. Conversely, H2EO depends mostly on its elevated viscosity and ester-based polar film to maintain a larger hydrodynamic layer; yet, during boundary lubrication at low loads, the protective composite film composed of PKO + MoS

2 + OA offers superior micro-scale asperity modification. This aligns with the observed correlation among enhanced nanoparticle dispersion, decreased friction, and diminished wear scar diameter in OA-containing systems, affirming that even slight improvements in dispersion when combined with a solid lubricant of intrinsically low shear strength can lead to substantial reductions in surface roughness.

At the weld load, the surface roughness findings reveal that PKO + CG + OA attains the lowest Ra value among all formulations, even surpassing the benchmark lubricant, hence illustrating the efficacy of integrating CG with OA in extreme pressure lubrication. Optical microscopy and dispersion analysis showed that OA decreased CG agglomeration, facilitating more uniform nanoparticle distribution in the contact zone. This stable dispersion enables the creation of a robust, load-bearing composite tribofilm, whereby oleic acid chemisorbs onto steel to produce an iron–oleate layer, while calcium glycerophosphate integrates into this layer, providing lamellar solid lubrication that occupies grooves on the surface and mitigates significant adhesive wear [

45]. However, PKO + MoS

2 without OA displays surface roughness at the weld site that is comparable to that seen with the benchmark lubricant, due to MoS

2’s intrinsic layered structure that facilitates shear and efficient load-bearing, while restricting dispersion enhancement. The incorporation of OA into MoS

2 unexpectedly enhances surface roughness, presumably due to OA’s insignificant stabilising effect on MoS

2 (agglomerate size alteration from 16.45 μm to 16.40 μm) and possible disruption of MoS

2 platelet arrangement at the contact interface, resulting in diminished cohesive tribofilm development. These trends align with the friction and wear scar diameter data, confirming that, under extreme pressure, superior nanoparticle dispersion stability such as in PKO + CG + OA yields smoother surfaces, while limited or counterproductive surfactant interaction, as in PKO + MoS

2 + OA, can diminish surface finish quality despite the presence of a solid lubricant.

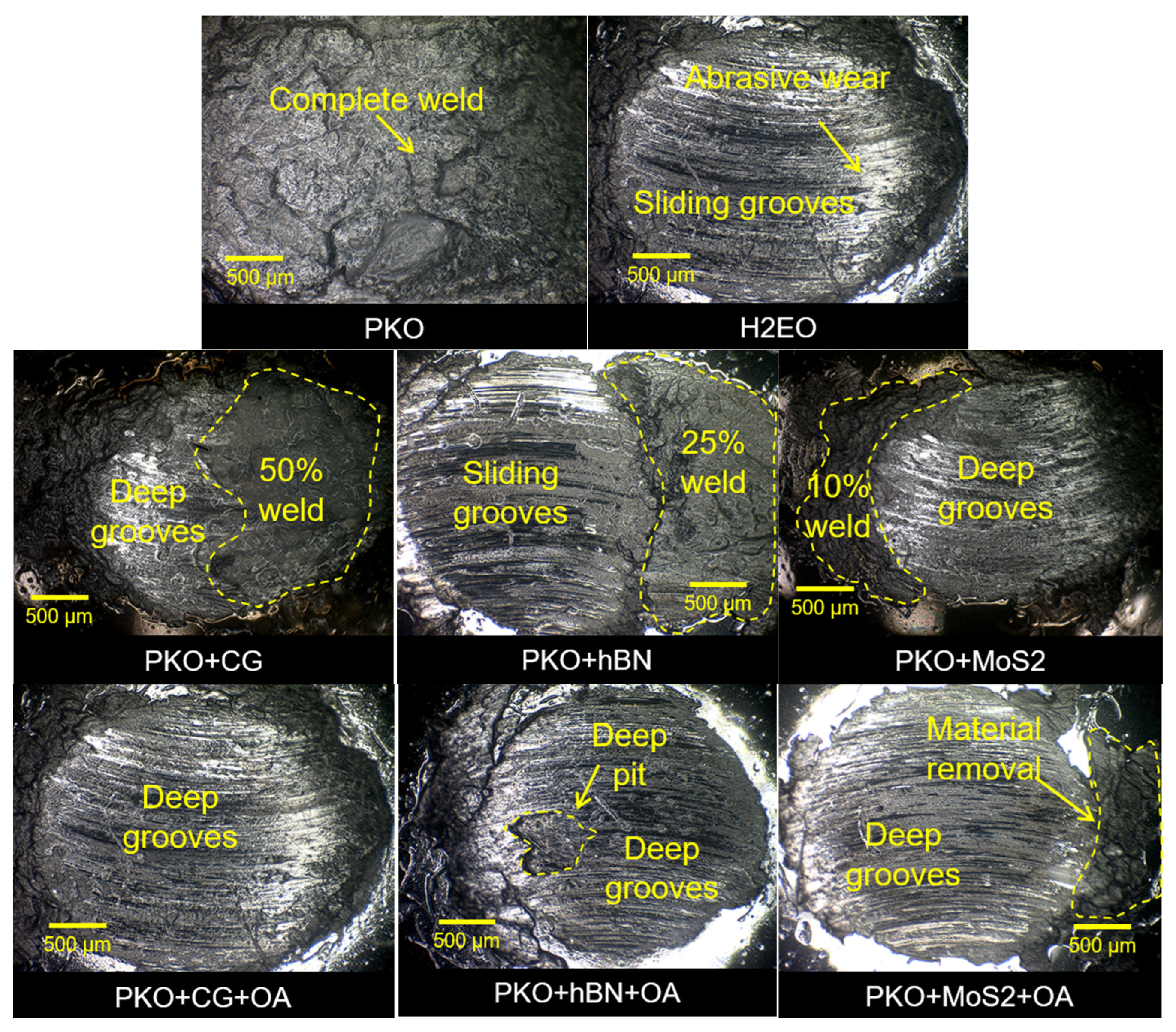

3.7. Analysis of Worn Surface

At a 110 kg load, the worn surface morphologies in

Figure 10 reveal distinct wear patterns that correlate closely with the measured surface roughness values. PKO + CG + OA exhibits the smoothest surface among all tested lubricants at this load, characterised by the presence of deep grooves but without large-scale material removal. This observation is consistent with its lowest Ra value and is attributed to the synergistic interaction between CG and OA. The incorporation of OA improves CG dispersion stability by 30.4%, reducing the agglomerate size from 17.61 µm to 12.23 µm, thereby promoting more uniform distribution of graphene platelets within the contact zone. These well-dispersed platelets interact with an OA-derived iron–oleate boundary layer to form a dense composite tribofilm that effectively patches micro-defects, sustains high contact stress, and mitigates severe adhesive wear.

In addition to its role in dispersion stabilisation, OA may also contribute through a surface-activity-mediated mechanism consistent with the Rehbinder effect. Under extreme pressure boundary lubrication, repeated asperity fracture and micro-welding events generate freshly exposed metallic surfaces [

27]. The adsorption or chemisorption of OA molecules on these nascent surfaces can reduce local surface energy, thereby weakening adhesive junctions and facilitating interfacial shear during sliding. Such surface-energy reduction does not alter the bulk mechanical properties of the steel but may locally modify the near-surface deformation behaviour, contributing to smoother shearing and reduced material pull-out [

37]. When coupled with load-sharing graphene platelets, this Rehbinder-type interfacial effect does not directly strengthen the tribofilm, but instead moderates adhesive junction growth and interfacial shear severity. By reducing the tendency for catastrophic adhesive pull-out during sliding, the surface-activity-mediated weakening of adhesion enables the graphene–oxide composite tribofilm to survive repeated high-load contact, thereby exhibiting enhanced endurance and surface integrity at elevated loads.

In comparison, the benchmark lubricant also maintains relatively low surface roughness but exhibits abrasive wear with distinct sliding grooves, indicating a different lubrication mechanism. Its wear protection stems primarily from its high viscosity and polar ester-based film, which provides stable fluid separation under load. However, without reinforcement from well-dispersed solid lubricants, the surface is more prone to groove formation from entrained debris [

46]. PKO + MoS

2 presents a surface finish comparable to benchmark lubricant, as reflected in its morphology showing only 10% weld area and deep grooves. This performance is largely due to the intrinsic lamellar structure of MoS

2, which facilitates low-shear interlayer sliding and reduces friction under high load conditions.

Conversely, the addition of OA to MoS2 (PKO + MoS2 + OA) results in increased surface roughness and more severe wear, including notable material removal. This outcome is supported by dispersion analysis, which shows that OA has minimal effect on MoS2 stability (agglomerate size change from 16.45 μm to 16.40 μm) and may even interfere with optimal platelet packing in the tribofilm. Such poor surfactant nanoparticle compatibility weakens the cohesion of the protective layer, allowing direct asperity contact and accelerating wear. Overall, these results confirm that, at 110 kg, nanoparticle dispersion stability plays a critical role in surface protection, with PKO + CG + OA forming the most resilient load-bearing film, while PKO + MoS2 + OA suffers from compromised tribofilm integrity despite containing a solid lubricant.

Table 4 presents the EDS spectra analysis of the worn surfaces after testing. The worn morphologies indicate the presence of surface fatigue and spalling pits, even though the PKO + CG + OA nanolubricant effectively reduced abrasive wear. Compared to PKO + CG (8.92 wt%), PKO + CG + OA exhibits a lower carbon content (7.39 wt%), suggesting a reduced extent of fatty-acid-derived carbonaceous species on the contact surface. Concurrently, lubrication with PKO + CG + OA resulted in a slightly higher oxygen concentration (3.98 wt% versus 3.89 wt%), indicating the formation of a more developed oxide layer.

The presence of this oxide-rich surface, together with organic carboxylate species consistent with oleic-acid-derived surface reactions, supports a lubrication mechanism dominated by tribofilm formation rather than simple fatty acid adsorption, as also reported by Bahari et al. [

47]. Under extreme pressure conditions, repeated asperity fracture and surface renewal expose fresh metallic surfaces, on which surface-active OA molecules may adsorb or react to form iron–oleate-type species. Such adsorption can locally reduce surface energy and weaken adhesive junctions, a behaviour consistent with a Rehbinder-type surface activity effect [

38]. This interfacial energy reduction facilitates easier shear at the sliding interface and suppresses severe adhesive pull-out, complementing the protective role of the oxide–carbon composite tribofilm.

For the hBN results, a comparison between PKO + hBN and PKO + hBN + OA revealed an increase in nitrogen content from 1.43% to 2.68%, suggesting a greater deposition of hBN nanoparticles on the worn ball surface. This implies the formation of a thicker hBN tribolayer, enhancing its ability to penetrate the contact zone and minimise direct metal-to-metal contact, thereby improving the lubricating performance of the PKO + hBN + OA nanolubricant. Conversely, the carbon content decreased substantially from 12.54 wt% to 7.39 wt%, indicating reduced adsorption of fatty acids on the worn surface. Additionally, oxygen content was lower for PKO + hBN + OA (2.54 wt%) compared to PKO + hBN (3.23 wt%), signifying reduced surface oxidation, likely due to the diminished fatty acid adsorption [

24].

The unstable lubricant film seen with the PKO + MoS

2 + OA nanolubricant is likely responsible for the observed increase in COF and WSD. EDS analysis showed lower Mo (1.18 wt%) and S (0.13 wt%) contents for PKO + MoS

2 + OA compared to PKO + MoS

2, which exhibited contents of 1.92 wt% and 0.13 wt%, respectively [

43]. This suggests that the OA surfactant reduced the deposition of MoS

2 nanoparticles on the contact surface, hindering the formation of a continuous protective film. In addition, the oxygen content on the worn surface lubricated with PKO + MoS

2 + OA (8.64 wt%) was significantly higher than that of PKO + MoS

2 (3.51 wt%), indicating the formation of an MoO3 transfer film. The results imply that OA promotes oxidation of MoS

2 nanoparticles during sliding, producing an unstable film that increases friction and wear, a phenomenon that is supported by previous findings [

48,

49]. Raman spectroscopy was conducted to confirm the presence of the MoO3 film. It was also previously reported that OA surfactant failed to reduce the agglomerate size of MoS

2 nanoparticles [

50]. This agglomeration during sliding reduces the number of nanoparticles able to penetrate the contact interface and adsorb onto the surface. Additionally, particle agglomeration may interfere with fatty acid adsorption on the worn surface. The EDS results confirmed this effect, showing that the carbon content decreased from 8.35 wt% in MoS

2 to 7.89 wt% in MoS

2 + OA, indicating reduced fatty acid adsorption for PKO + MoS

2 + OA compared to the PKO + MoS

2 nanolubricant. This reduction in both nanoparticle deposition and fatty acid adsorption likely contributed to the poorer tribological performance of the OA-containing formulation [

39].

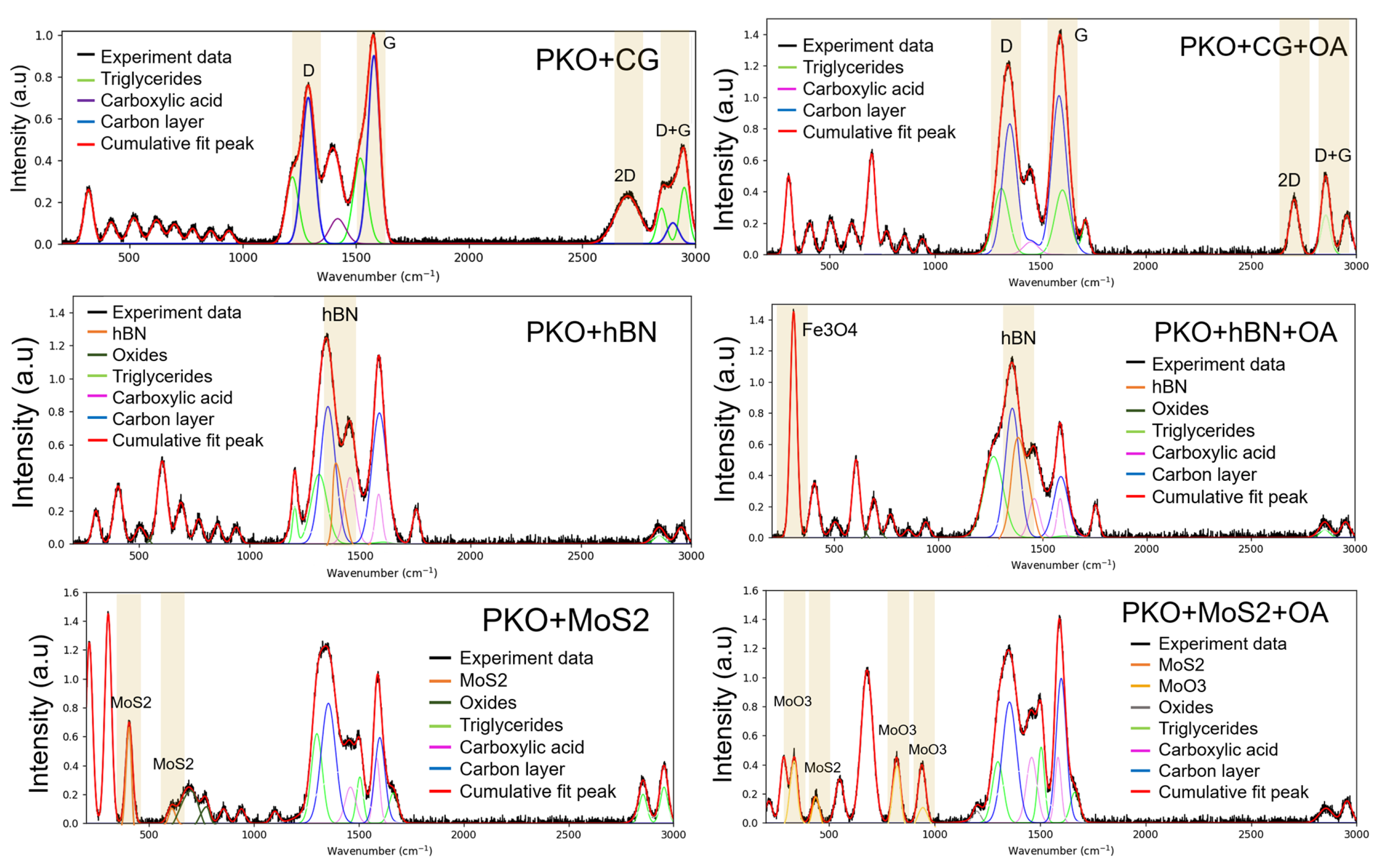

3.8. Analysis of the Chemical Composition of the Worn Surface

The deconvoluted Raman spectra of the worn surfaces that were lubricated with the PKO + CG and PKO + CG + OA nanolubricants are shown in

Figure 11. When PKO + CG + OA was introduced to a worn surface, the iron carboxylate peaks were weaker than when PKO + CG was used alone, indicating that the production of metallic soap films was further reduced. These findings corroborate those from the VPSEM-EDS analysis, which showed that the worn surface had a reduced carbon content [

51]. Compared to PKO + CG alone, the PKO + CG + OA nanolubricant probably enabled more CG nanoparticles to access the sliding contact due to its better dispersion stability. Metallic soap film development is reduced due to the increased concentration of CG at the contact zone, which seems to limit the adsorption of fatty acid molecules onto the steel surface [

33]. Furthermore, it seems that there are more free-floating fatty acid molecules in the contact area rather than bound ones to the steel surface, as shown by the higher intensity at 1706 cm

−1.

The VPSEM-EDS findings are further supported by the Raman analysis. Wear on surfaces coated with the PKO + CG + OA nanolubricant was accompanied by a more substantial oxide layer compared with the PKO + CG nanolubricant. The development of one well-known lubricious oxide, Fe

3O

4, which may help reduce metal-to-metal contact, was induced by the addition of OA surfactant [

52]. Additional friction and wear prevention has been seen in some instances when a composite lubricating layer made of carbon and iron oxide is applied [

53]. Additionally, the presence of the D, G, and 2D bands in the spectra provided further evidence that CG particles were able to penetrate the sliding contact, deposit on the worn surface, and aid in the formation of a protective tribofilm. The presence of OA resulted in a lower ID/IG ratio (0.83) for the surface lubricated with the PKO + CG + OA nanolubricant compared to the PKO + CG nanolubricant (0.97), indicating that a more ordered tribofilm was formed. Previous research has shown that ordered tribofilms on sliding surfaces are responsible for the better lubricating behaviour of carbon-based nanomaterials, and this suggests that structural ordering is associated with improved lubrication performance [

54,

55].

Analysing the deconvoluted Raman spectra of the lubricated surfaces that were worn down with the PKO + hBN and PKO + hBN + OA nanolubricants demonstrated that the Fe3O4 peaks were not as strong in the PKO + hBN + OA sample as they were with the PKO + hBN nanolubricant, indicating that there was less iron oxide deposited on the contact surface. Sliding was shown to cause an increase in the intensity at 810 cm

−1, which corresponds to Cr (III) oxide, suggesting the opposite. The fact that Cr (III) oxide has been shown to help reduce friction makes this even more beneficial [

56].

Figure 11 also shows that the worn surface that was lubricated with PKO + hBN + OA displays the Raman signatures of iron carboxylates at 933, 1427, and 1559 cm

−1. Based on the spectra, it seems that the bridging configuration was somewhat less significant in adsorption than monodentate coordination. There was a clear drop in 1427 cm

−1 peak intensity compared to the PKO + hBN nanolubricant, suggesting that fewer iron carboxylates bound via bridging modes. The strength of the carbonaceous layer’s distinctive D and G bands was also significantly reduced in PKO + hBN + OA compared to PKO + hBN [

57]. These spectrum results are in agreement with the VPSEM-EDS study, which validated the Raman results by confirming a significant decrease in surface carbon content for the PKO + hBN + OA lubricated surface.

The Raman spectra of the worn surfaces that were lubricated with the PKO + MoS

2 and PKO + MoS

2 + OA nanolubricants are shown in

Figure 11. In the PKO + MoS

2 + OA system, specific peaks at 522 cm

−1 and 673 cm

−1 were identified as Cr

2O

3 and Fe

3O

4, respectively. The production of a thicker iron oxide layer was suggested by the substantially greater peak intensity of the Fe

3O

4 compared to PKO + MoS

2 alone. This finding is in line with what the VPSEM-EDS analysis revealed: that the worn surface had a much higher oxygen content. At 922, 1382, and 1557 cm

−1, iron carboxylate bands were seen in the PKO + MoS

2 + OA spectra. A greater percentage of bridging contacts on the steel surface lubricated with PKO + MoS

2 + OA is indicated by the more intense 1382 cm

−1 peak compared to the 1377 cm

−1 peak of PKO + MoS

2 in the PKO + MoS

2 spectrum. On the other hand, the PKO + MoS

2 spectrum’s stronger 1559 cm

−1 band implies that monodentate bonding was more common when OA was not present. Furthermore, when contrasted with the metallic soap film produced by PKO + MoS

2 alone, the PKO + MoS

2 + OA nanolubricant displayed a more organised and compact appearance. The peaks at 2839 and 2954 cm

−1 were less intense compared to the peaks at 2851 and 2935 cm

−1 for PKO + MoS

2, suggesting that the molecules were packed closer together in the film. The addition of OA surfactant significantly altered the structure and behaviour of MoS

2 with the PKO + MoS

2 nanolubricant. The Raman spectra revealed the formation of defective MoS

2 nanoparticles and nonstoichiometric phases, along with the transformation of MoS

2 into MoO3, as indicated by peaks at 287, 817, and 955 cm

−1. The presence of MoO3 promoted abrasive wear and explained the increased surface roughness of the worn surface lubricated with PKO + MoS

2 + OA [

49,

50]. These findings suggest that OA induced higher structural defects in MoS

2, reducing its ability to adsorb and form a stable protective film, thereby increasing friction and wear compared to PKO + MoS

2 nanolubricant.

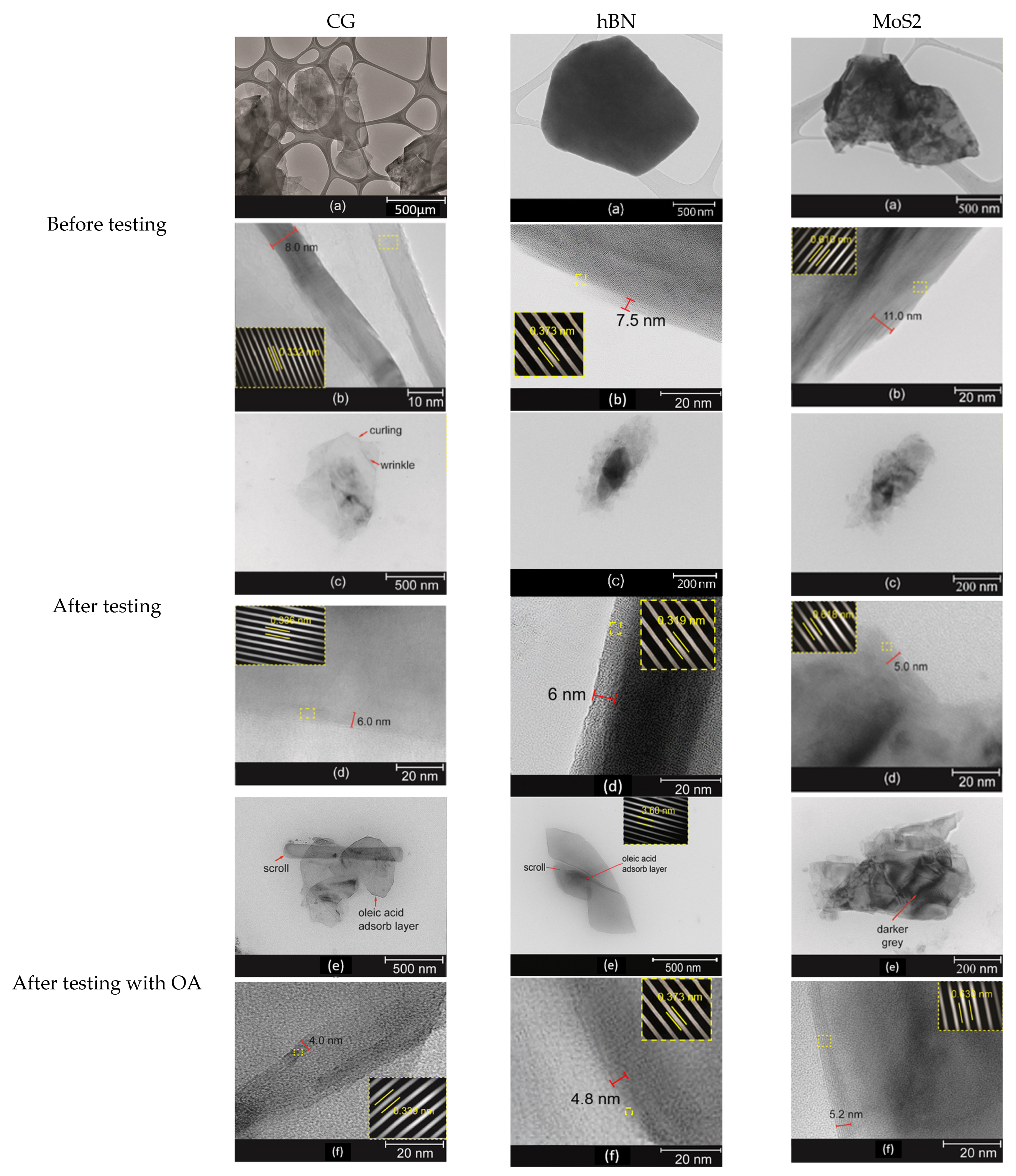

TEM analysis provided crucial insights into the structural evolution of CG, hBN, and MoS

2 nanoparticles dispersed in palm kernel oil (PKO) before and after tribological testing (see

Figure 12). The exfoliation of CG and MoS

2 was evident from the reduced thickness and enlarged interlayer spacing, as seen in the transition from 8.0 nm to 4.0 nm for CG and from 11.0 nm to 5.2 nm for MoS

2, respectively. These morphological changes suggest that continuous shearing during sliding facilitated the delamination of multilayer structures into thinner nanosheets, thereby increasing the effective contact area for tribofilm formation. In contrast, hBN maintained its layered morphology with a moderate decrease in thickness (~7.5 nm to 4.8 nm), indicating that it acted primarily as a solid lubricant with stable lattice integrity. The presence of oleic acid (OA) was found to form a uniform adsorption layer around all three nanomaterials, preventing severe agglomeration and promoting better dispersion stability within the PKO medium. This stable distribution likely enhanced the nanoparticles’ ability to enter the contact interface, resulting in improved anti-wear and load-bearing properties [

33].

The observed microstructural behaviour aligns closely with the macroscopic tribological performance, confirming OA’s decisive role in enhancing PKO-based nanolubricants. The reduction in CG agglomeration by 30.4% and the improvement in viscosity index (from 176 to 188) suggest that OA effectively stabilised the nanoparticles under EP. Consequently, the PKO + CG + OA formulation exhibited the most significant friction reduction (51.7%) and wear scar minimization (13.4%), attributed to the synergistic exfoliation intercalation mechanism where OA molecules penetrated between nanoparticle layers to form an elastic “spring-like” tribofilm. Meanwhile, the moderate enhancement observed with PKO + hBN + OA and PKO + MoS2 + OA indicates that hBN contributed mainly through surface rolling effects, while MoS2 offered lamellar shear support. These findings demonstrate that OA-assisted PKO nanolubricants exhibit superior lubrication stability, improved thermal endurance, and enhanced protective tribofilm formation, highlighting their potential as sustainable, bio-based formulations for demanding extreme pressure and high-shear tribological conditions.