Abstract

The low-frequency sensitivity of gravitational-wave detectors can be degraded by noise arising from the re-coupling of stray light with the main interferometer beam. This review describes the re-coupling mechanism and shows how the experience gained with current detectors can be used to anticipate and mitigate stray-light issues in third-generation instruments. We summarize the work carried out on numerical simulations and on the extensive characterization of stray light originating from both core and auxiliary optics. We also discuss possible improvements to the interferometric readout system aimed at reducing stray-light-induced noise, as well as diagnostic approaches for identifying potentially harmful scattering elements. Overall, this review summarizes best practices for the effective control of stray light in future gravitational-wave detectors, supporting design approaches aimed at preventing unforeseen noise issues.

1. Introduction

Stray light is the unwanted light that is scattered, reflected, or diffused away from its intended path and unintentionally re-enters the optical system, potentially causing noise or interference. In Gravitational-Wave Interferometric Detectors [1,2,3,4], it refers to light that escapes the main beam, interacts with surfaces or optics, and then couples back into the interferometer’s main field, degrading sensitivity. This phenomenon is among the dominant noise sources at low frequencies, a crucial band for many key astrophysical observations [5]. There are two main mechanisms for stray light to recombine with the main interferometer field, mainly related to the virtual port involved in the coupling of the noise. Let us note that in gravitational waves detector interferometers, the term core optics refers to the (generally suspended) optical components which form the main interferometer, e.g., the mirrors of the arm Fabry–Perot cavities, the optics of the Power Recycling and Signal Extraction/Recycling cavities, the main beam splitter, and any possible transmissive optics sitting in the main interferometer. Output ports is a term which refers instead to any optical access through which (part of) the main interferometer beam can leave the interferometer, either by design or by unavoidable imperfections.

- 1.

- Light scattered off the core optics of the interferometer can impinge on mechanical structures and be scattered/reflected back to the same or different core optics, where a third scattering event could recombine a fraction of the spurious field with the interferometer main mode [6,7].

- 2.

- Light leaving an interferometer output port traverses multiple optical components, which can reflect or scatter part of it back into the instrument. This returning field can interfere with the main mode, producing a time-varying spurious contribution whose phase and amplitude carry the imprint of the optical element motion [8,9,10,11,12].

Already from that basic description, it is clear that the best way to prevent stray light from being produced is to restrict the interaction of the laser beam to as few optical components as strictly needed.

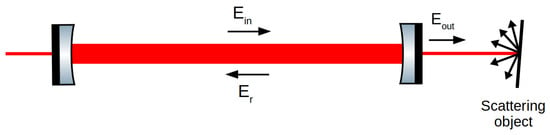

Following the approach of [8], represents the interferometer’s internal field at a reference position, chosen for its relevance to the assessment of stray-light coupling to the detector sensitivity. referes to the optical field emerging from one port of the interferometer at the position of the stray light source. denotes the portion of this field that is scattered or reflected back and then recoupled into the main interferometer mode at the reference location where is evaluated, as shown in Figure 1. We define the phase of the field which encodes the relative time-dependent motion between the interferometer and the scattering or reflecting object:

where is the wavelength of the interferometer’s field.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the stray-light coupling: the input field propagates inside the interferometry, while the field exits the cavity and impinges on a scattering object. The resulting back-scattered and back-reflected field re-enters the cavity, propagating in the direction opposite to [13].

The stray light field adds to the unperturbed interferometer field , giving the output field

where is a static phase which depends on the scattering or reflecting object position with respect to the reference point in the interferometer, is the fraction of stray light exiting the detector output port which recouples back into the main mode, and and are output and input powers, respectively. The ratio is considered 1.

The factor receives contributions from multiple sources

where accounts for the light back-scattered from a surface, for the specular reflection, represents the light back-scattered by atoms or molecules (in crystals for example), and is the extra contribution of scattered light coming from spurious beams.

The back-scattered contribution is an intrinsic contribution of each optical element and is proportional to the bi-directional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) of the surface by means of the approximate relationship [8]

where is the beam radius at the scattering surface and the scattering angle. There are several optical measurement setups that allow the BRDF of optical components to be directly characterized in the laboratory [14]. An approximation for cases in which this measurement cannot be performed and/or the scattered light is assumed to be uniformly distributed over a 2-steradian hemisphere (Lambertian Scattering regime [15]) is to use the total integrated scattering (TIS) measured from the object and divide it by to obtain an estimate of the BRDF.

The back reflection contribution accounts for the light back-reflected towards the interferometer by surfaces that are almost perpendicular to the beam. Its expression for an optical element with reflectivity can be estimated as the overlap integral between the incoming beam and the back-reflected beam , , and can be computed analytically by assuming that the incoming mode is purely Gaussian as [8]

where R is the radius of curvature of the reflecting surface, D is the distance between the surface and the beam waist position, is the beam Rayleigh range, and is the small angle at which the optic is tilted.

The Rayleigh scattering contribution arises from microscopic inhomogeneities or small imperfections within a solid medium. In high-quality optical materials, these microscopic variations represent the dominant source of scattering losses. The scattering recombination coefficient can be expressed as [16]

where is the wavelength, n is the refractive index, p is the photo-elastic constant, is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, is the isothermal compressibility of the material, and l is the length of the medium. This expression is derived under the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium, valid for liquids and gases, and it can still be applied to amorphous materials by considering the structural fluctuations set at the glass transition temperature rather than the ambient one.

The final contribution, , corresponds to the fraction of light scattered by various parasitic beams generated within the optical system that can subsequently re-couple into the interferometer’s main beam. To identify and mitigate this source, it is necessary to simulate the paths of these parasitic beams throughout the system, implement measures to block them, and estimate the potential contribution of each to the overall noise. Each of these steps will be described throughout this paper.

The total field in Equation (2) contains contributions in both orthogonal quadratures, amplitude and phase, because the complex exponential in encodes both the cosine and sine components of the field. Starting from this complete output field, the projection of the stray-light noise can be derived by evaluating its contribution to each quadrature:

where represents the Fourier transform and and are the phase and amplitude quadrature transfer functions from the port where the scatterer/reflector is located to the gravitational-wave signal, i.e., the linear response of the interferometer phase and amplitude noises.

This expression makes clear that stray light affects detector sensitivity through two main contributions: the relative motion between the scattering object and the interferometer and the amount of stray light actually recombined . The relative motion can be minimized by improving the performance of mechanical suspension systems, while the amount of recombined stray light depends mostly on the optical features [9,17]. In the following, we focus on the optical contribution to stray-light noise, reviewing mitigation strategies and best practices relevant for next-generation detectors such as the Einstein Telescope (ET) [18] and Cosmic Explorer (CE) [19]. These instruments aim for a sensitivity roughly ten times better than current detectors, making stringent control of scattered light critical, even as optical systems become more complex. Leveraging the studies and strategies developed in current detectors will be essential to ensure that future observatories are not limited by stray light.

It is worth noting here that all the clever techniques and ideas developed by the gravitational-wave community for controlling stray light can be easily spoiled by the contamination of optical surfaces due to improper handling and/or poor cleanliness standards. The performance of interferometer optical components (scattering, absorption, laser-induced damage threshold) can be compromised by even minimal levels of particulate contamination. Mitigation strategies involve quantifying contamination, identifying sources, improving practices to reduce particle generation, developing in situ cleaning for suspended optics, qualifying cleanliness standards against potential damage, and creating remote measurement and cleaning methods for optics in a vacuum (see for instance [20,21]).

2. Stray Light from Core Optics

The interferometer main laser field interacts with core optics and a tiny part of it experiences a scattering due to unavoidable surface imperfections and roughness. The scattering mechanism is described in Section 1. It is worth stressing that the whole recombination process requires, in that case, at least three scattering/reflection events: scattering off a given core optic, interaction with an external structure (either scattering or reflection), and further scattering off a core optic to the interferometer main mode. If one of the events has a negligible scattering efficiency, then the whole process is largely disfavored. Since the BRDF value involved in the wide-angle scattering from core optics is of the order of few ppm, the most harmful scattering process is linked to the small-angle scattering due to low-spatial-frequency figure errors.

The strategies used to cope with that type of scattering noise generally involve the following:

- Mitigating the amount of stray light which can scatter off the core optics, by employing precision polishing and coating control;

- Preventing the stray light from wandering until it can recombine the main mode, usually by means of absorbing baffles in the arms, vacuum links, and around the core optics themselves.

State-of-the-art polishing techniques to achieve the required surface roughness rely on advances such as magnetorheological finishing (MRF) [22], ion-beam figuring (IBF) [23], and super-polishing with colloidal suspension slurries [24,25].

High-quality coatings suppress scatter by reducing micro-roughness and internal defects [26,27]. Future approaches include the following:

- Ion-beam sputtered (IBS) amorphous materials;

- Crystalline coatings (e.g., AlGaAs);

- Metasurfaces designed to reduce scattering at specific angles.

Minimizing scatter from core optics requires achieving sub-Å RMS surface roughness across apertures of the size of few beam diameters. State-of-the-art workflows combining magnetorheological finishing (MRF), ion-beam figuring (IBF), and colloidal super-polishing routinely achieve ∼ nm RMS roughness, limiting the noise due to surface scatter below coating thermal noise and well within stray-light budgets [15,28,29].

Ion-beam sputtered dielectric stacks and emerging crystalline coatings preserve substrate roughness and suppress high-spatial-frequency noise growth. High-uniformity IBS coatings and crystalline GaAs/AlGaAs layers have shown near-perfect roughness transfer and reduced scatter losses critical for ET and CE [30,31].

Operating at longer wavelengths (e.g., 1.55–2 μm silicon test masses for Low-Frequency detector of ET) reduces Rayleigh scattering (), allowing looser microscopic roughness constraints while supporting cryogenic operation [32,33].

Low-scatter absorbing baffles and mechanical structure shielding prevent stray photons from re-entering the interferometer mode. Research into metamaterial and nanotextured absorbing surfaces offers improved angular absorption and reduced retro-reflection compared to traditional blackening [34,35].

Metasurfaces and engineered sub-wavelength texturing can shape the bidirectional scattering distribution function (BSDF), directing unwanted scatter into lossy angular regions and suppressing low-angle feedback pathways [36,37]. These techniques are promising for isolating beam tubes and auxiliary optics for future generations of Gravitational-Wave Interferometers, where traditional baffling is insufficient.

A slightly different mechanism concerning stray light from core optics occurs when the primary source of stray light is the ghost beam coming from the residual reflection off anti-reflective coated surfaces. In that case, while it still holds true that better coatings can minimize the amplitude of such a ghost beam, a tilt of the AR-coated surface is also of primary importance to steer the ghost beam towards a safe termination. This tilt can be achieved either by tilting the whole optics if possible (e.g., for the compensation plates used for correcting the thermal aberrations) or by providing the AR-coated surface with a wedge (e.g., as for the back surface of the main beam splitter). In both cases, the angle is chosen in order to minimize losses in the main beam. This often implies small angles (of the order of ∼hundreds of , and the necessity to separate the related ghost beams from the main mode at the output of suitable telescopes on suspended output benches. Particular attention has to be paid in the optical design phase to allow proper clearance to the ghost beams until they reach their intended termination.

3. Stray Light from Auxiliary Optics

Gravitational-wave detectors are highly complex instruments that, in addition to their core optics, rely on numerous suspended optical benches hosting auxiliary optics required to operate the various feedback loops that keep the interferometer at its working point.

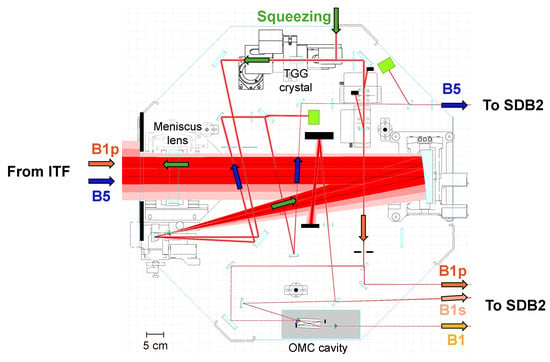

An illustration of the complexity of these optical benches is provided in Figure 2, which shows Suspended Detection Bench 1 (SDB1), one of Virgo’s detection benches located at the interferometer’s output port. Stray light generated on the detection benches couples back into the interferometer far more efficiently than light scattered elsewhere, owing to the large transfer function associated with the output port. The bench shown in Figure 2 contains numerous optical elements that give rise to all the recoupling mechanisms described in Section 1. Light is back-scattered from optical surfaces and photodiode windows. Some lenses, being nearly perpendicular to the incident beam, also reflect light backward into the interferometer. Moreover, Rayleigh scattering occurs within the crystals, and the high optical density of the bench leads to numerous parasitic reflections that can further contribute to back-scattering.

Figure 2.

One of Virgo’s suspended detection benches, the Suspended Detection Bench 1 (SDB1), receives the B5 beam (Michelson beam splitter reflection) and the B1p beam (output beam) from the interferometer. A portion of the B1p beam is transmitted through the Output Mode Cleaner (OMC) cavity, forming the B1 beam that carries the gravitational-wave signal, while the reflected component, B1s, is also directed toward Suspended Detection Bench 2 (SDB2). Figure adapted from [13].

Over the years, several studies, analyses, and mitigation strategies have been carried out to reduce the impact of this noise on the detector. The following subsections summarize the main results and lessons learned, which are crucial for the design of next-generation gravitational-wave detectors.

3.1. Reduction of Back-Scattering and Rayleigh Light

The estimation of the amount of back-scattered light that couples back into the interferometer beam can be obtained either from manufacturer specifications or from laboratory measurements [14]. The components that contribute most to scattering on the Virgo benches include the following:

- The coatings of crystals mounted on the benches, such as the TGG (Terbium Gallium Garnet) crystals in the Faraday isolators [38,39] and the monolithic fused silica cavity of the Output Mode Cleaner (OMC, Suprasil 3001) [40].

- Light retro-reflected by the filter cavity in the frequency-dependent squeezing system [41,42], which is subsequently amplified by the nonlinear crystal generating the squeezed field, i.e., the optical parametric oscillator (OPO) [43].

- Windows of photodiodes or quadrant photodiodes, which exhibit relatively high BRDF values.

The residual motion of the filter cavity must be minimized as much as possible, since any displacement directly increases back-scattered light and its coupling into the interferometer. To further reduce retro-reflected light, the number and placement of Faraday isolators between the cavity and the interferometer need to be carefully optimized. In Virgo’s squeezing system, an active control loop has also been tested to suppress stray light originating from an independent diagnostic local oscillator. Although this scattered light is absent when the squeezed beam is injected, developing such mitigation techniques is crucial to prevent potential noise sources from affecting science-mode operation [13]. A control scheme aimed at de-amplifying the back-scattered light inside the OPO, thereby reducing the noise it produces in the GEO600 detector [44], has also been successfully demonstrated [45]. Moreover, it is crucial to characterize a priori in the laboratory the scattered light produced by photodiodes and quadrant detectors before installation, as their measured BRDF ranges widely between 3 < BRDF < [46].

As for the TGG crystal inside the Faraday isolator, although it is tilted by about 1 deg to avoid back-reflection, it still contributes significantly to back-scattering due to optical surface roughness and internal material scattering [47]. In LIGO, studies are ongoing to replace the Faraday material with the magneto-optic crystal KTF (potassium terbium fluoride) [48] to reduce absorption losses affecting the squeezing. However, this change would increase the crystal’s total scattering by a factor of four. Therefore, further research is needed to identify low-loss materials with reduced scattering [39].

The Virgo output mode cleaner is a monolithic fused silica cavity (Suprasil 3001), which generates scattering both from its optical surfaces and from the bulk material itself. This scattered light is critical for the interferometer’s sensitivity, as back-scattered light can be amplified by the cavity by a factor proportional to its finesse, even though retro-reflected light is attenuated by when passing back through the Faraday isolator. Replacing this monolithic cavity with an open design, as in LIGO, could help reduce the amount of back-scattered light reaching the interferometer by eliminating contributions from Rayleigh scattering [16].

3.2. Reduction of Back-Reflected Light

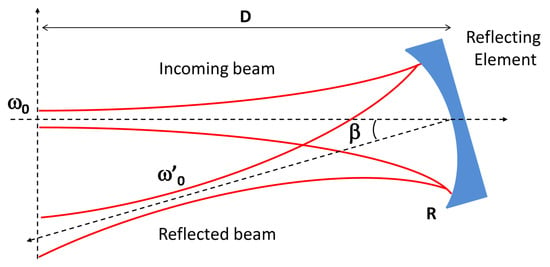

The dominant contribution to back-reflected light re-coupling into the interferometer beam originates from the lenses. As shown in Equation (5), the fraction of light that re-couples decreases exponentially with the tilt angle of the reflecting surface, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of how a Gaussian beam is back-reflected by a surface. and are the waists of the incident and reflected beams, respectively. D is the distance between the beam waist position and the surface with reflectance R, and is the tilt angle of the surface [8].

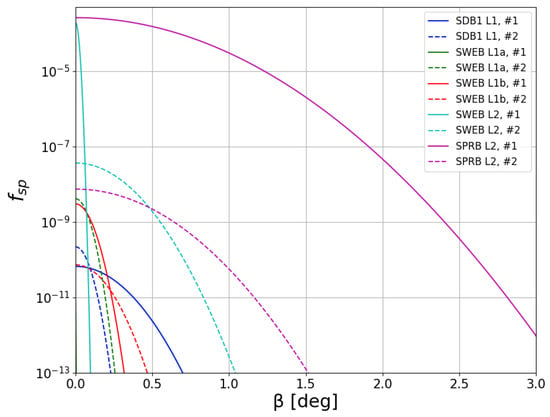

The contribution from certain lenses located on the suspended benches of Virgo, as a function of their tilt angle, is shown in Figure 4, considering both surfaces of each lens. This contribution decreases rapidly with increasing tilt angle, emphasizing the importance of avoiding completely untitled lenses. Most lenses on the benches can—and should—be tilted by approximately 1 deg to achieve a safe operating condition, as implemented in Virgo during the upgrade between the O3 and O4 observing runs. It is important to underline that tilting the lenses would introduce astigmatism to the transmitted beam. This effect can be taken care of by performing optical simulations, but generally it is a negligible effect. Furthermore, it is crucial to dump the direct reflections from the lenses onto an absorbing surface to prevent the reflected light from scattering off other optical components. The Virgo benches also feature large meniscus lenses (see the entrance of the bench in Figure 2), 4 inches in diameter, which are positioned perpendicular to the beam or for which the tilt angles are unknown. Due to their size and fixed mounts, these lenses cannot currently be tilted. Assuming a null or minimal tilt angle, their contribution is comparable to other major scattering sources. For future upgrades, replacing these fixed mounts with motorized ones is recommended, allowing controlled tilting and enabling a systematic study of scattered-light behavior as a function of lens tilt.

Figure 4.

Contribution for some of the most critical lenses on Advanced Virgo Plus benches [13]: Suspended Detection Bench 1 (SDB1), Suspended West End Bench (SWEB), Suspended Power Recycling Bench (SPRB).

3.3. Reduction of Scattering from Spurious Beams

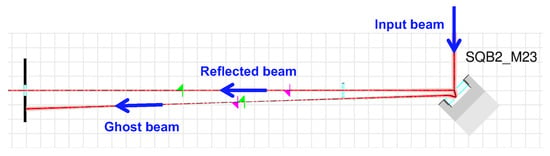

Spurious beams, known as ghost beams, arise from residual reflections and transmissions within optical elements, depending on the residual reflectivity and transmissivity of their coatings or substrates. Figure 5 shows a simulation of ghost-beam generation: the incident beam is partially transmitted through the first surface of a mirror, then partially reflected by the second surface, and finally transmitted again in a direction determined by the mirror’s wedge angle. As this beam propagates, it can encounter scattering surfaces, and a fraction of it may re-couple into the interferometer beam.

Figure 5.

Ghost beam generated by not-perfect mirror coatings ending up on an absorbing surface [13].

In Virgo, ghost beams have been systematically traced using the software Optocad [49] on all suspended benches, and several mitigation strategies have been implemented:

- Installation of beam dumps to intercept them;

- Re-orientation of mirrors to change the direction of their wedge to make it easier to dump them;

- Gluing of absorbing glass pieces onto the mounts of lenses, photodiodes, and mirrors to block residual beams without requiring additional space.

A systematic study of this kind will also be essential for future gravitational-wave detectors, in order to allocate space for beam dumps and other absorbing solutions, and to ensure that this contribution does not compromise the instrument sensitivity.

4. Simulation of Stray Light in Gravitational-Wave Interferometers

The pre-emptive simulations of the effects due to stray light is of paramount importance to be able to implement mitigations directly during the design phase of the interferometric detectors. Indeed, the effort to modelize and predict the impact of stray light noise predates by far the construction of current interferometers and is contemporary to the initial study of the detectors [6,7,50]. Several tools have been developed and employed during this decade-long challenge, and nowadays a few of them have proven to be effective enough to steer the design of mitigation solutions.

4.1. Small-Angle Scattering: FFT-Based Propagation Tools

When the relevant mirror-surface perturbations are dominated by low spatial-frequency height errors, the scattered field remains confined to a narrow angular cone relative to the Gaussian main beam—typically an issue in the long arm cavities. In this regime, FFT-based angular-spectrum propagation tools [51,52,53,54,55] are ideally suited for predicting stray-light amplitudes and mode content across multiple sequential scattering events. A typical simulation chain models three conceptually distinct steps: (i) a first scattering event from a test-mass mirror, (ii) a second scattering event from a baffle or tube wall at the far end of the arm cavity, and (iii) a third scattering event returning toward the original test mass, generating the fraction of light that is coherent enough to recombine with the fundamental interferometer mode.

This three-stage FFT simulation workflow provides a self-consistent method to estimate the full coherent stray-light coupling chain associated with low-angle scattering from core optics. The method integrates detailed mirror maps, baffle geometry, and (measured or modeled) BRDF data. Furthermore, the basic principle of simulation naturally encompasses the diffraction mechanism once the correct geometry (aperture profile and distance) is provided. It has been successfully employed for the design of Advanced Virgo baffles [56], and for the development of scattering budgets in the arms of the Einstein Telescope [57,58]. As such, FFT-based multi-stage small-angle scattering simulations constitute a mature and indispensable tool for controlling stray-light noise in next-generation gravitational-wave interferometers.

4.2. High-Spatial-Frequency Scattering: Ray-Tracing and Hybrid Recombination Models

Surface defects with high spatial frequency scatter light at large angles, producing fields that propagate far from the main interferometer mode and eventually strike vacuum-tube walls, baffles, or optical-bench components. These wide-angle processes cannot be efficiently simulated using FFT-based wave-propagation tools, whose grid resolution requirements become prohibitive when representing small-scale defects on large optical surfaces. Instead, ray-tracing methods are routinely adopted to estimate how much power is removed from the main beam, how it is redistributed in angle, and which fraction geometrically returns toward the interferometer after one or more reflections. This approach has been applied successfully to port optics and benches in Advanced Virgo and related setups [59,60]. The main software tools used to carry out this kind of approach are OpticStudio (formerly Zemax) [61] and FRED [62] for the non-sequential ray-tracing, while an ad hoc phase-aware ray-tracing tool was developed to an initial stage in [60].

Ray-tracing naturally accounts for complex three-dimensional geometry, but it does not preserve optical phase information and therefore cannot, by itself, predict the coherent recombination of returned light with the fundamental interferometer mode. A second analytical or semi-analytical step is therefore required to estimate the coupling efficiency. This is typically done by assigning a representative phase model to the returned rays, constructing an approximate field distribution at the interferometer aperture, and evaluating its overlap with the interferometer eigenmode. A coherence factor, derived from the distribution of path-length differences and the laser coherence length, determines whether the returned light produces stationary phase noise or merely adds incoherent background power. This hybrid procedure provides realistic engineering estimates of stray-light coupling in situations dominated by large-angle scatter—particularly on optical benches, where numerous reflective surfaces and apertures create a dense network of potential scattering paths.

The main limitations arise from uncertainties in the phase properties of scattered fields and from the simplified treatment of the microscopic scattering process. Ray-tracing cannot capture coherent interference between nearby scattering sites or diffraction associated with intermediate apertures. Moreover, BRDF models for real surfaces often involve poorly constrained parameters, especially for contaminated, aged, or angle-dependent coatings. As a result, current predictions may underestimate or overestimate coherent recombination in cases where geometric and wave effects coexist.

Different software programs were also developed within the community of Gravitational-Wave Interferometers to have a visual representation of the optical path followed by the main interferometer beam and by higher-order reflections and transmissions, in order to predict potential interactions of the laser field with mechanical structures and optical apertures. These software programs belong to the family of non-sequential Gaussian beam tracers, a feature that is currently lacking in other commercial software such as OpticStudio (formerly Zemax) [61] and FRED [62], which are able to either propagate the beam with Physical Optics in sequential mode (the user provides the sequence of optical surfaces to interact with) or to trace the beam with Geometrical Optics in non-sequential mode. Optocad [49] was one of the first tools being developed for this purpose, and despite the limitations (not maintained anymore, only 2D tracing capabilities) is still one of the most used tool to analyse the path of both the main beam and of spurious ghost beams (see Section 3.3). Nevertheless, it appeared soon evident that a 3D tracing capability was needed to correctly account for out-of-plane reflections or transmissions and the development of additional tools was pursued through the years, although with different results and pace. Software programs actually used for the design and the analysis of current and future generation Gravitational-Wave Interferometers are Ifocad [63] and Theia [64], among others.

Future progress will likely come from integrated simulation frameworks that combine ray-tracing with localized wave-optics calculations, for example by embedding high-resolution FFT “patches” at critical scattering surfaces or by propagating the angular spectrum of ray-traced returns using paraxial field solvers. Improved BRDF measurements for relevant optical and mechanical components, as well as systematic coherence modeling informed by in situ diagnostics, will further reduce uncertainties. Together, such developments will allow more accurate and computationally efficient stray-light budgets for third-generation gravitational-wave detectors.

5. Readout Schemes for Stray-Light Immunity

Readout architectures can decrease how strongly parasitic scattered light couples into the gravitational-wave signal, by reducing coherent coupling with stray fields or enabling their active suppression. Balanced homodyne detection provides improved common-mode rejection and flexible quadrature choice, while dual-readout and witness-channel approaches allow construction of noise-orthogonal combinations that isolate and subtract stray-light–dominated components. Additional techniques—such as modulation/tagging schemes—further discriminate parasitic fields from the scientific signal. Together, these approaches offer a complementary pathway to mitigating scattered-light noise at the readout, and motivate dedicated development for third-generation detectors.

5.1. Dual Balanced Homodyne/Dual Readout

A powerful strategy to increase immunity to stray-light noise is to use a dual balanced homodyne readout architecture, where two independent balanced detection chains are employed and combined. An auxiliary readout provides a witness signal for parasitic optical fields, enabling active subtraction of stray-light noise from the main gravitational-wave channel. Experiments demonstrate that dual readout allows us to model the parasitic scattered-light contribution and subtract it effectively, yielding significant reductions of back-scatter noise in table-top interferometers. Subtraction fidelity depends on the witness signal-to-noise ratio and the degree of linear coupling between stray-light paths and the science readout. Accurate calibration and phase control of the local oscillator are required [65].

5.2. Tunable Coherence/Coherence Engineering

Another advanced mitigation approach is to modify or tune the coherence properties of the interferometer laser so that scattered light returning from ancillary paths remains only partially coherent with the main carrier. Techniques such as pseudo-random phase modulation or coherence tailoring can convert coherent parasitic interference into incoherent fluctuations or shift it to a spectral regime that is easier to reject. Recent experiments using tunable coherence demonstrated suppression of stray-light noise by drastically reducing the coherence length without compromising interferometer control or scientific signal recovery [66].

5.3. Witness Sensors and Adaptive Feedforward Subtraction

The addition of witness sensors to monitor scattered-light fields and mechanical motion of optic mounts enables data-driven subtraction of back-scattering noise from the readout. Auxiliary photodiodes placed near baffles or apertures, quadrant photodiodes monitoring scattered-mode content, and vibration sensors on scattering elements provide correlated channels for Wiener-filter or adaptive subtraction. This method can significantly reduce stray-light contamination, provided that witness channels have sufficiently high signal-to-noise ratios and are linearly related to the stray-light coupling paths. Care must be taken to avoid over-subtraction or inadvertent removal of astrophysical signal content [67].

5.4. Modulation and Tagging Schemes

Stray-light robustness can also be enhanced by optical tagging techniques, where specific phase or frequency modulation patterns are applied to the interferometer carrier or local oscillator. Fields that undergo unintended scattering paths then accumulate distinguishable modulation signatures, which enables selective demodulation or rejection of parasitic interference products. This approach can also be interpreted as a generalization of heterodyne readout, where additional sideband structure and multi-tone demodulation help discriminate genuine gravitational-wave signals from scattered-light artifacts. These methods introduce complexity in locking and control, but offer a systematic means to separate coherent interferometric signal from stray-field contamination [68,69].

6. Tools for Diagnosing Stray Light Sources

The availability of diagnostic instruments to measure stray light in such complex systems as Gravitational-Wave Interferometers is essential to assess whether the setup is properly aligned, whether the components behave as expected, and whether any dust contamination has altered the amount of light scattered by a given optic. A relevant advancement in this field is the realization of photosensor-equipped baffles (or instrumented baffles). These devices allow the reconstruction of the diffused light pattern they intercept with a resolution given by the distribution of sensors on the baffle surface. This piece of information can be used to gain a deeper insight on the defects giving raise to the scattered light and alert on their possible evolution [70,71]. A strategic placement of this kind of devices in the future Gravitational-Wave Interferometers will allow us to gather a comprehensive view on the status of the stray light inside the interferometer.

Studies of this kind are also at an advanced stage in the LISA space-based gravitational-wave detector project [72]. In fact, an instrument capable of identifying the position of the optics responsible for stray light has been developed and tested [73]. In this instrument, which generalizes the Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry (OFDR) technique, stray light introduces an additional optical path with respect to the nominal beam. Since the laser undergoes a linear frequency sweep, this path difference manifests as a beat signal at a well-defined frequency. The relationship between the beat frequency and the optical path difference is

where is the frequency sweep rate of the incident beam, n is the refractive index, and c is the speed of light. The term represents the temporal delay between the two beams. Thus, the beat frequency is simply the product of this delay and the sweep rate, implying that larger optical path differences generate higher beat frequencies and can therefore be detected and quantified.

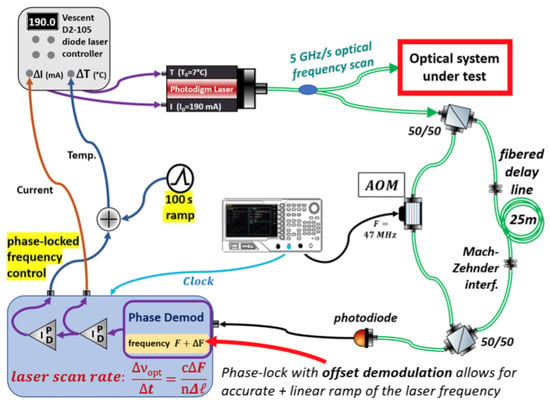

The frequency ramp must be linear for this relationship to remain valid, and it is generated through a feedback loop using an unbalanced heterodyne Mach–Zehnder interferometer in fiber to produce an error signal, with current actuation and a temperature ramp.

As shown in Figure 6, the demodulated interferometer phase is , where the frequency offset , set by the Mach–Zehnder arm imbalance , is directly related to the sweep rate:

where is the refractive index of the fiber and c is the speed of light.

A similar instrument is being developed for the Virgo gravitational-wave detector [74], which is undergoing planned upgrades that include the installation of new optical benches. Verifying that these benches do not introduce excessive stray light before they are put in place is therefore highly desirable. Moreover, having a diagnostic tool for periodic checks is essential to ensure that the system remains well-controlled over time. This approach will be even more critical for future gravitational-wave detectors, where the stray-light requirements are expected to be more stringent due to their increased sensitivity.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the device that generates a laser frequency sweep, allowing the amplitude of the stray-light peak to be identified as a function of the optical path distance [75].

7. Stray-Light Noise Projections

In order to be able to prevent and predict excess of stray light originating from optics in the next generations of Gravitational-Wave Interferometers, a priori noise projections are mandatory to verify whether the expected stray light level remains well below the sensitivity curve.

For instance, in Virgo, the projected contribution of stray light originating from the optical benches has been evaluated starting from Equation (7) [13]. In this analysis, was estimated using Equations (4)–(6), together with the available measurements [14]. The corresponding transfer function was obtained from detector simulations, while the motion was derived from Virgo seismic data acquired by sensors located near the optical element under test.

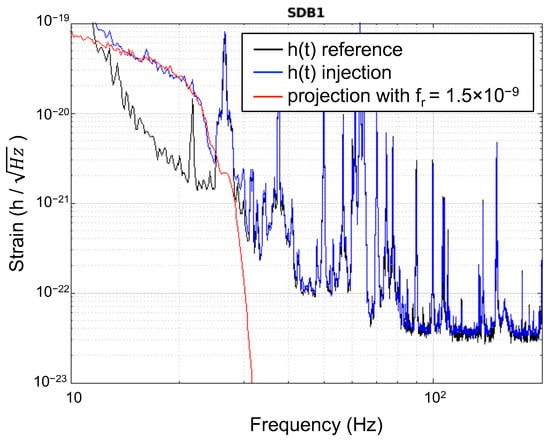

The estimated value can be experimentally verified by injecting a sinusoidal noise onto the suspensions of the suspended bench hosting the optics of interest. The introduction of a sinusoidal displacement noise greater than the wavelength of the laser into the stray-light path produces the phenomenon of fringe wrapping, which appears as a shoulder-shaped feature in the noise spectrum, as shown by the blue curve in Figure 7 for the suspended detection bench 1 (SDB1) in Virgo. The associated cutoff frequency can be expressed as [76] follows:

where is the velocity of the scatterer, the wavelength of the laser, and the amplitude of the motion of the scatterer. Once the value has been determined, it can be compared with the estimated one. A noise projection can then be performed, again based on Equation (7), but this time using the high- and low-seismic measurements recorded by sensors near the optical element under study, instead of a noise injection in [77,78]. This allows us to assess whether stray-light noise is safely below the interferometer’s sensitivity curve or if it could become relevant under unusually high seismic conditions.

Figure 7.

Measurement performed in 2023 on the Virgo detection bench SDB1: the black curve is the Virgo sensitivity curve, the blue curve represents the sensitivity during a sinusoidal noise injection with amplitude , the red curve is the stray light noise projection during the injection [79].

Performing similar projections for different components of third-generation gravitational-wave detectors, based on available data or realistic estimates, provides a way to ensure that all elements are operating within acceptable limits and to identify potential issues before installation.

8. Conclusions

Stray light has long been recognized as a significant limitation to the low-frequency performance of laser-interferometric gravitational-wave detectors, and experience from the current generation of observatories has demonstrated that its impact can be both subtle and severe. Parasitic optical fields originate from a diverse set of mechanisms—surface and coating defects, auxiliary-optics scatter, unintended apertures, and structured vacuum components—that create paths capable of re-coupling into the interferometer’s fundamental mode. Once injected into the readout chain, such fields probe mechanically driven structures and imprint non-linear, displacement-dependent noise that is difficult to predict and highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Despite extensive mitigation efforts, stray light has repeatedly limited, or come close to limiting, detector performance, demonstrating the need for more predictive strategies.

Over the past decades, extensive scatter measurements, BRDF characterizations, and commissioning campaigns have provided a detailed empirical basis for understanding stray-light generation and coupling mechanisms. Complementary progress in numerical tools—FFT-based wave simulations, hybrid wave–ray models, and Monte-Carlo scattering pipelines—has enabled identification of key scattering paths and supported more reliable stray-light budgeting. These developments have clarified essential design principles for third-generation detectors: removal of direct line-of-sight paths, implementation of low-scatter baffling, strict BRDF control of exposed surfaces, and reduction of mechanically driven scatterers through improved suspension design and the selection of seismically quiet sites.

Advances in materials and surface engineering offer additional opportunities. Ultra-low-scatter substrates, improved super-polishing, low-defect coatings, and engineered absorbing surfaces (e.g., meta- and nano-structured materials) promise to reduce primary stray-light generation at its source. Their systematic qualification under high-power operation will be crucial for next-generation observatories.

Readout-side strategies provide a complementary route to enhanced robustness. Dual balanced or dual homodyne readout, coherence-tailored laser sources, and modulation-tagging schemes have demonstrated the ability to suppress or subtract the influence of parasitic fields by improving common-mode rejection, reducing coherence with scattered light, or enabling noise-orthogonal data combinations. These techniques are likely to become increasingly relevant as third-generation detectors push toward more demanding low-frequency performance.

Looking forward, a more predictive and diagnostic-oriented methodology will be essential. Early stray-light noise projections should accompany both optical and mechanical design, and dedicated diagnostic tools—scatter probes, temporary witness channels, and systematic BRDF verification—should be integrated into commissioning to identify problematic scattering elements before installation or early in operation.

In summary, effective stray-light mitigation for third-generation gravitational-wave detectors requires a system-level approach combining improved materials, optimized scattering geometries, mechanically quiet infrastructure, advanced diagnostics, and readout architectures explicitly engineered for stray-light immunity. Integrating these strategies from the earliest design phases will be essential for achieving the ambitious sensitivity goals of future gravitational-wave observatories.

As such, stray-light control should be considered a central pillar of third-generation detector development, on par with quantum-noise reduction, thermal-noise engineering, and seismic isolation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P. and A.C.; methodology, E.P. and A.C.; formal analysis, E.P. and A.C.; bibliography, E.P. and A.C.; investigation, E.P. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, E.P. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created for the study reported in the present paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aasi, J.; Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.; Abernathy, M.R.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; et al. Advanced LIGO. Class. Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 074001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acernese, F.; Agathos, M.; Agatsuma, K.; Aisa, D.; Allemandou, N.; Allocca, A.; Amarni, J.; Astone, P.; Balestri, G.; Ballardin, G.; et al. Advanced Virgo: A Second-Generation Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detector. Class. Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAGRA Collaboration. KAGRA: 2.5 Generation Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detector. Nat. Astron. 2019, 3, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billing, H.; Winkler, W.; Maischberger, K.; Rüdiger, A.; Schilling, R.; Schnupp, L. An Argon laser interferometer for gravitational wave detection. J. Phys. Sci. Instruments 1979, 12, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abac, A.; Abramo, R.; Albanesi, S.; Albertini, A.; Agapito, A.; Agathos, M.; Albertus, C.; Andersson, N.; Andrade, T.; Andreoni, I.; et al. The Science of the Einstein Telescope. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinet, J.Y.; Brisson, V.; Braccini, S.; Ferrante, I.; Pinard, L.; Bondu, F.; Tournefier, E. Scattered light noise in gravitational wave interferometric detectors: A statistical approach. Phys. Rev. D 1997, 56, 6085–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinet, J.Y.; Brisson, V.; Braccini, S. Scattered light noise in gravitational wave interferometric detectors: Coherent effects. Phys. Rev. D 1996, 54, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuel, B.; Genin, E.; Vajente, G.; Marque, J. Displacement noise from back scattering and specular reflection of input optics in advanced gravitational wave detectors. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 10546–10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Austin, C.; Effler, A.; Schofield, R.M.S.; González, G.; Frolov, V.V.; Driggers, J.C.; Pele, A.; Urban, A.L.; Valdes, G.; et al. Reducing scattered light in LIGO’s third observing run. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 38, 025016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Bianchi, S.; Plastino, W.; Arnaud, N.; Chiummo, A.; Fiori, I.; Swinkels, B.; Was, M. Scattered light noise characterisation at the Virgo interferometer with tvf-EMD adaptive algorithm. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 145011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Was, M.; Gouaty, R.; Bonnand, R. End benches scattered light modelling and subtraction in advanced Virgo. Class. Quantum Gravity 2021, 38, 075020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polini, E. Stray Light Issues and Control in Advanced Virgo Plus; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polini, E. Broadband Quantum Noise Reduction in Advanced Virgo Plus: From Frequency-Dependent Squeezing Implementation to Detection Losses and Stray Light Mitigation; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Was, M.; Polini, E. High-angular-resolution interferometric backscatter meter. Opt. Lett. 2022, 47, 2334–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, J.C. Optical Scattering: Measurement and Analysis; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ju, L.; Flaminio, R.; Lück, H.; Zhao, C.; Blair, D.G. Rayleigh scattering in fused silica samples for gravitational wave detectors. Opt. Commun. 2011, 284, 4732–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koehlenbeck, S.M.; Mow-Lowry, C.M.; Bergmann, G.; Kirchoff, R.; Koch, P.; Kühn, G.; Lehmann, J.; Oppermann, P.; Wöhler, J.; Wu, D.S. A study on motion reduction for suspended platforms used in gravitational wave detectors. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punturo, M.; Abernathy, M.; Acernese, F.; Allen, B.; Andersson, N.; Arun, K.; Barone, F.; Barr, B.; Barsuglia, M.; Beker, M.; et al. The Einstein Telescope: A third-generation gravitational wave observatory. Class. Quantum Gravity 2010, 27, 194002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitze, D.; Adhikari, R.X.; Ballmer, S.; Barish, B.; Barsotti, L.; Billingsley, G.; Brown, D.A.; Chen, Y.; Coyne, D.; Eisenstein, R.; et al. Cosmic explorer: The US contribution to gravitational-wave astronomy beyond LIGO. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.04833. [Google Scholar]

- Gushwa, K.E.; Torrie, C.I. Coming clean: Understanding and mitigating optical contamination and laser induced damage in advanced LIGO. In Proceedings of the Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 2014; Exarhos, G.J., Gruzdev, V.E., Menapace, J.A., Ristau, D., Soileau, M., Ristau, D., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatello, A.; Ciani, G.; Conti, L. Scattered light noise due to dust particles contamination in the vacuum pipes of the Einstein Telescope. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.26919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.M.; Yang, Y.-K.; Lin, J.-Q.; Du, Y.-S.; Zhou, X.-Q. Research progress of magnetorheological polishing technology. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 19, 642–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, M.; Huang, L.; Bouet, N.; Kaznatcheev, K.; Vescovi, M.; Lauer, K.; Conley, R.; Rennie, K.; Kahn, J.; Nethery, R.; et al. A one-dimensional ion beam figuring system for X-ray mirrors. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2015, 86, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xin, Q.; Fan, B.; Chen, Q.; Deng, Y. A Review of Emerging Technologies in Ultra-Smooth Optical Surface Fabrication. Micromachines 2024, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbo, M.J.; Fairhurst, D.; Jacobs, S.D.; Puchebner, B.E. Slurry particle size evolution during the polishing of optical glass. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 3743–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinlechner, J. Development of mirror coatings for gravitational-wave detectors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2018, 376, 20170121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Martin, I. Development of mirror coatings for gravitational wave detectors. Coatings 2016, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.; Alok, A.; Das, M. Magnetorheological method applied to optics polishing: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 804, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Peng, L.; Wang, J. Ultra-smooth polishing of high-precision optical surface. Optik 2013, 124, 6586–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, G.D.; Zhang, W.; Martin, M.J.; Ye, J.; Aspelmeyer, M. Tenfold reduction of Brownian noise in high-reflectivity optical coatings. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, G.M.; the LIGO Scientific Collaboration. Thermal noise in interferometric gravitational wave detectors due to dielectric optical coatings. Class. Quantum Gravity 2007, 24, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccasecca, S. Silicon test masses for cryogenic gravitational wave detectors. Class. Quantum Gravity 2018, 35, 235004. [Google Scholar]

- The Einstein Telescope Collaboration. Einstein Telescope Design Report (Update 2020). ET Technical Note: ET-0007C-20. Available from the Einstein Telescope Document Server. 2024. Available online: https://apps.et-gw.eu/tds/ql/?c=15418 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Luo, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, Y.; Chen, L. Ultra-broadband, polarization-independent, wide-angle near-perfect absorber incorporating a one-dimensional meta-surface with refractory materials from UV to the near-infrared region. Opt. Mater. Express 2020, 10, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasaninejad, M.; Capasso, F. Metalenses: Versatile multifunctional photonic components. Science 2017, 358, eaam8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbabi, A.; Horie, Y.; Bagheri, M.; Faraon, A. Dielectric metasurfaces for complete control of phase and polarization with subwavelength spatial resolution and high transmission. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Wang, J.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Qu, S. Transparent metasurface for wideband backward scattering reduction with synthetic optimization algorithm. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 275002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franta, D.; Muresan, M.; Ondračka, P.; Hroncová, B.; Vižďa, F. Wide spectral range optical characterization of terbium gallium garnet (TGG) single crystal by universal dispersion model. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, D.; Snetkov, I.; Li, J. A review on magneto-optical ceramics for Faraday isolators. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 873–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouaty, R.; Was, M. Specifications for the Polishing of the Advanced Virgo “Mode Cleaner” Cavities; Technical Report VIR-0535A-21; The Virgo Collaboration Technical Documentation System: Cascina, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Acernese, F.; Agathos, M.; Ain, A.; Albanesi, S.; Alléné, C.; Allocca, A.; Amato, A.; Amra, C.; Andia, M.; Andrade, T.; et al. Frequency-Dependent Squeezed Vacuum Source for the Advanced Virgo Gravitational-Wave Detector. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 041403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, D.; Jia, W.; Nakano, M.; Xu, V.; Aritomi, N.; Cullen, T.; Kijbunchoo, N.; Dwyer, S.E.; Mullavey, A.; McCuller, L.; et al. Broadband Quantum Enhancement of the LIGO Detectors with Frequency-Dependent Squeezing. Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13, 041021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuller, L.; Barsotti, L.; Evans, M.; Fritschel, P. Design Requirements Document of the A+ Filter Cavity and Relay Optics for Squeezing Injection; Technical Report T1800447-v7; LIGO: Hanford, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Affeldt, C.; Danzmann, K.; Dooley, K.L.; Grote, H.; Hewitson, M.; Hild, S.; Hough, J.; Leong, J.; Lück, H.; Prijatelj, M. Advanced techniques in GEO 600. Class. Quantum Gravity 2014, 31, 224002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamin, F.; Lough, J.; Schreiber, E.; Grote, H.; Mehmet, M.; Vahlbruch, H.; Affeldt, C.; Andric, T.; Bisht, A.; Brinkmann, M.; et al. Characterization and evasion of backscattered light in the squeezed-light enhanced gravitational wave interferometer GEO 600. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 38443–38456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Was, M.; Gouaty, R.; Polini, E.; Stehlin, K. Measurement of Optics and Sensors with an Interferometric Scatter Meter; Technical Report VIR-0997A-21; Virgo Collaboration Technical Documentation System: Cascina, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://tds.virgo-gw.eu/ql/?c=17246 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Yoshida, H.; Tsubakimoto, K.; Fujimoto, Y.; Mikami, K.; Fujita, H.; Miyanaga, N.; Nozawa, H.; Yagi, H.; Yanagitani, T.; Nagata, Y.; et al. Optical properties and Faraday effect of ceramic terbium gallium garnet for a room temperature Faraday rotator. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 15181–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, J.; David, T. Temperature Dependent Excess Optical Path Length Measurements in KTF and TGG; Technical Report G2400512-v1; LIGO Laboratory Documentation Center: Hanford, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, R. OptoCad—A Fortran 95 Module for Tracing Gaussian TEM00 Beams Through an Optical Set-Up. Available online: https://www.rzg.mpg.de/~ros/Optocad (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Flanagan, E.; Thorne, K.S. Noise Due to Backscatter Off Baffles, the Nearby Wall, and Objects at the Fare End of the Beam Tube; and Recommended Actions. 1994. Available online: https://dcc.ligo.org/LIGO-T940063/public (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Edo, T.; Romero, A.; Yamamoto, H. SIS20 Documents. 2020. Available online: https://dcc.ligo.org/LIGO-T2000311-v2/public (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Degallaix, J. OSCAR a Matlab based optical FFT code. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 228, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinet, J.Y.; Hello, P.; Man, C.; Brillet, A. A high accuracy method for the simulation of non-ideal optical cavities. J. Phys. I 1992, 2, 1287–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Day, R.A. Accelerated convergence method for fast Fourier transform simulation of coupled cavities. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2014, 31, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.A. A New FFT Code: FOG, Fast Fourier Transform Optical Simulation of Gravitational Wave Interferometers (Presentation). Conference Slides (GWADW 2012). Gravitational-Wave Advanced Detector Workshop (GWADW) Held on 14 May 2012 in Waikoloa Marriott Resort, Hawaii. 2012. Available online: https://dcc.ligo.org/LIGO-G1200629/public (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Chiummo, A. Stray Light Control Subsystem in AdV @SLworkshop; Technical Report VIR-0751A-20; Virgo Collaboration Technical Documentation System: Cascina, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://tds.virgo-gw.eu/ql/?c=15876 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Andrés-Carcasona, M.; Macquet, A.; Martínez, M.; Mir, L.M.; Yamamoto, H. Study of scattered light in the main arms of the Einstein Telescope gravitational wave detector. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Carcasona, M.; Umbert, J.G.; González-Lociga, D.; Martínez, M.; Mir, L.M.; Yamamoto, H. New modeling of the stray light noise in the main arms of the Einstein Telescope. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.18083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, B. Numerical Simulations of Stray Light in Virgo. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Genova, Genoa, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- González Castro, J.M. Noise from Stray Light in Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detectors. Ph.D. Thesis, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ansys Zemax OpticStudio Comprehensive Optical Design Software. Available online: https://www.ansys.com/products/optics/ansys-zemax-opticstudio (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- FRED Optical Engineering Software. Available online: https://photonengr.com/fred (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Kochkina, E.; Wanner, G.; Schmelzer, D.; Tröbs, M.; Heinzel, G. Modeling of the general astigmatic Gaussian beam and its propagation through 3D optical systems. Appl. Opt. 2013, 52, 6030–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, R. Theia: A Novel 3D Gaussian Beam Tracer—Traineeship Report; Technical Report VIR-0693A-17; Virgo Collaboration Technical Documentation Center: Cascina, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://tds.virgo-gw.eu/ql/?c=12626 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Lohde, A.; Voigt, D.; Gerberding, O. Dual balanced readout for scattered light noise mitigation in Michelson interferometers. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, D.; Eggers, L.; Isleif, K.S.; Koehlenbeck, S.M.; Ast, M.; Gerberding, O. Tunable Coherence Laser Interferometry: Demonstrating 40 dB of Stray Light Suppression and Compatibility with Resonant Optical Cavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 213802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinders, M.; Schnabel, R. Sensitivity improvement of a laser interferometer limited by inelastic back-scattering, employing dual readout. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1501.05219. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1501.05219 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Hild, S. DC-readout of a signal-recycled gravitational wave detector. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0811.3242. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/0811.3242 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Fritschel, P. Readout options for advanced gravitational-wave detectors. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Gravitational Waves (ICGW2001), the University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 8–13 July 2001; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, O.; Blanch, O.; Cardiel, L.; Cavalli-Sforza, M.; Chiummo, A.; García, C.; Illa, J.M.; Karathanasis, C.; Kolstein, M.; Martinez, M.; et al. Measurement of the stray light in the Advanced Virgo input mode cleaner cavity using an instrumented baffle. Class. Quantum Gravity 2022, 39, 115011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Carcasona, M.; Martínez, M.; Mir, L.M.; Mundet, J.; Yamamoto, H. Performance of an instrumented baffle placed at the entrance of Virgo’s end mirror vacuum tower during O5. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro-Seoane, P.; Audley, H.; Babak, S.; Baker, J.; Barausse, E.; Bender, P.; Berti, E.; Binétruy, P.; Błaut, A.; Bohe, A.; et al. Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.00786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubeau-Tissot, A. Interférométrie à DéRive de FréQuence Pour la Mesure de la LumièRe Parasite sur l’Instrument Spatial LISA. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Virgo Collaboration. Advanced Virgo Plus for O5—Technical Design Report; Technical Report VIR-0499A-25; Virgo Collaboration Technical Documentation Center: Cascina, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lintz, M.; Roubeau-Tissot, A.; Nardello, M.; Cleva, F. Measurement and identification of coherent stray light in complex interferometers, application to the LISA interferometric Detection System. In Proceedings of the GRASS GRAvitational-Waves Science & Technology Symposium (GRASS 2024), Trento, Italy, 1 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marque, J.; Tournefier, E.; Canuel, B.; Fiori, I. Diffused Light Mitigation in Virgo and Constraints for Virgo+; Technical Report VIR-0792A-09; Virgo Collaboration: Cascina, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Polini, E.; Yin, X. Back-Scattered Light from OFI at LIGO Hanford. Gravitational-Wave Advanced Detector Workshop—2023. Hotel Hermitage, La Biodola, Isola d’Elba, 21–27 Mag 2023. Available online: https://agenda.infn.it/event/32907/contributions/201726/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Polini, E. OMC Scattered Light Noise Study in LHO. LIGO Technical Report in Document Control Center: LIGO-G2301690-v1. 2023. Available online: https://dcc.ligo.org/LIGO-G2301690 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Hui, V.; Conti, L.; Gouaty, R.; Was, M.; Zendri, J.P. Scattered Light Noise Measurements for DET Benches; Technical Report VIR-0449A-23; Virgo Collaboration Technical Documentation System: Cascina, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.