Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Using a Multidisciplinary Team Approach: A Single-Center Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

2.2. Surgical Technique

2.3. Outcomes/Impact of MDHT Roles and Contributions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort

3.2. Peri-Operative Outcomes

3.3. Impact of MDHT Roles and Contributions

- 1.

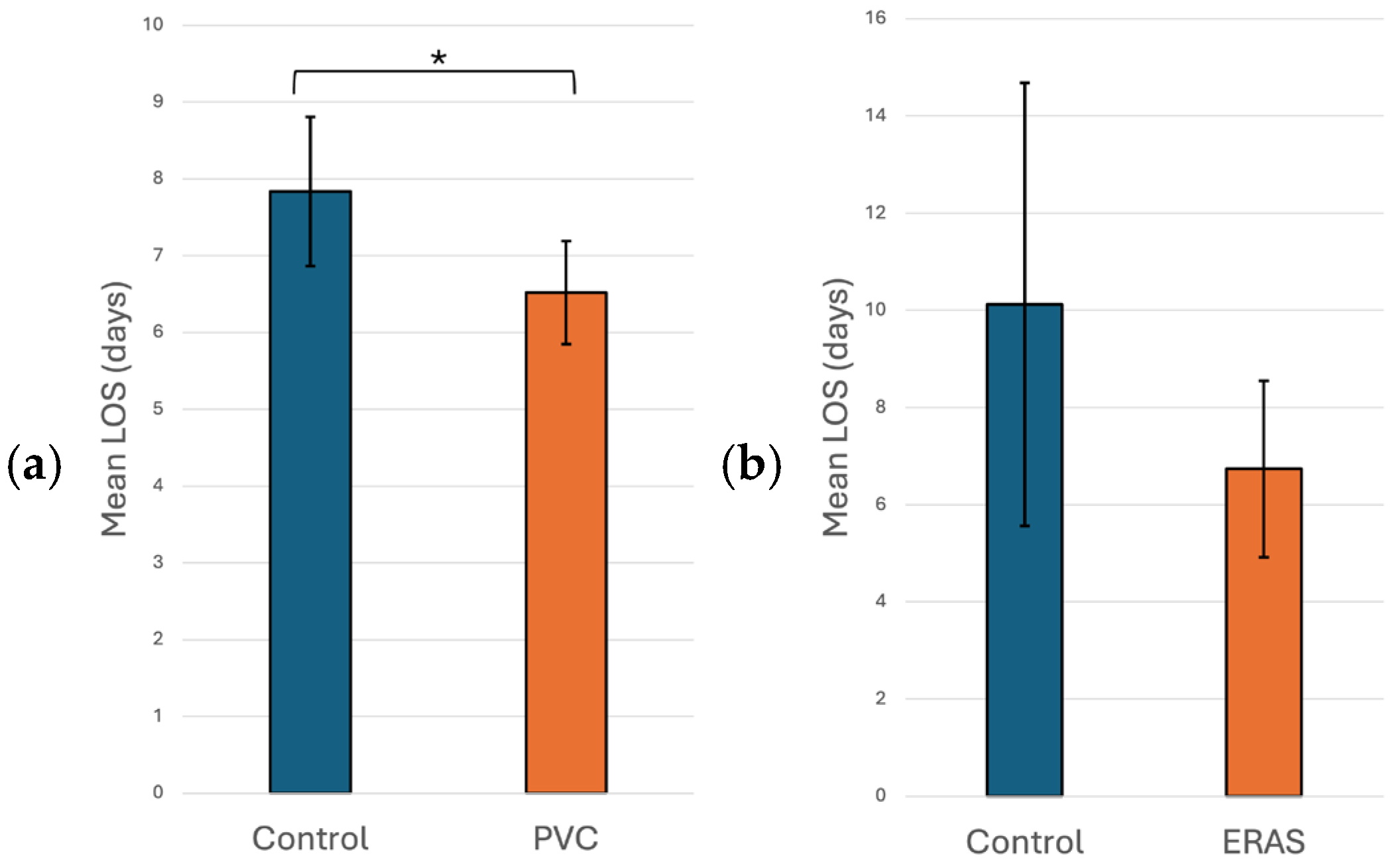

- Anaesthesiology: Many aspects of mini-thoracotomy MVR/MVr require additional skills on the part of our anesthesia colleagues. We use a bronchial blocker to isolate the right lung and rely on the TEE skills of the cardiac anesthesiologist to show us the mitral valve pathology and place a retrograde cardioplegia cannula. At our institution, they also perform percutaneous right internal jugular cannulation for superior vena cava drainage. However, the greatest impact that our anesthesia colleagues have made is in the management of post-operative pain, which has been a source of major morbidity following mini-thoracotomy mitral valve surgery. In an attempt to mitigate this, our cardiac anesthesia group started to use regional anesthesia through the placement of a paravertebral catheter (PVC). The PVC is inserted on the side of the surgery before the induction of anesthesia. This procedure was performed by an anesthesiologist trained in ultrasound or landmark-based placement with the patient in the sitting position. A total of 135 (48.6%) patients received PVC-based regional anesthesia, which was associated with a statistically significant shorter hospital LOS compared to no PVC use (6.52 vs. 7.81 days, p = 0.028), as seen in Figure 1a. This was likely due to reduced pain, as patients subjectively appeared more comfortable and mobile when a PVC was used. Unfortunately, pain scores were not available to quantify the impact of PVC use on pain.In the univariate non-linear regression model, the expected LOS for patients in the PVC group was about 11.8% shorter compared with patients in the control group (p = 0.028). After adjusting for significant risk factors (i.e., age, sex, and ejection fraction) in the multiple regression analysis, patients who had a PVC still had a significantly shorter LOS than control group patients, with the expected LOS for patients in the PVC group being about 16.9% shorter compared with patients in the control group (p = 0.019; Table 4).

- 2.

- Interventional Cardiology: Prior to 2019, all patients undergoing minimally invasive MVR/MVr were cannulated femorally through a small cut-down in the groin for direct cannulation of the femoral artery and vein. Using this technique, we noticed that some patients developed persistent lymphoceles at this site. Under the instruction and supervision of our interventional cardiology colleagues, we switched to percutaneous cannulation of the femoral artery and vein, using the “preclose” technique for the artery as developed for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Prior to the implementation of percutaneous cannulation, 11 patients developed post-operative lymphoceles (11/178 patients, 6.2%). In comparison, 100 (36.0%) cases were carried out using percutaneous cannulation, with no incidence of lymphoceles in this group of patients (0/100 patients, 0%).

- 3.

- Operative Nursing: The operative nursing team has had to adapt to using a completely different set of instruments, as regular instruments cannot be used through a small mini-thoracotomy incision. As such, long-shafted instruments are used instead, which requires some adaptation on the part of the operative nursing team. One particularly difficult maneuver with long-shafted instruments is the tying of knots. This can be time-consuming, with an increased risk of air knots and/or broken sutures. At our institution, the operative nursing team is in control of all OR instrumentation purchases. With their assistance, we were able to bring the COR-KNOT® DEVICE to our institution to eliminate the need to tie knots manually. In the 132 (47.5%) patients in whom COR-KNOTs were used, there was a statistically significant 38 min decrease in OR time when compared to patients who had knots tied with long-shafted instruments (288 vs. 326 min, p < 0.001), as seen in Figure 2.In the univariate non-linear regression model, the expected operative time for patients in the COR-KNOT® DEVICE group was about 12.6% shorter compared with patients in the control group (p < 0.001). After adjusting for significant risk factors (i.e., sex, BMI, and surgery time) in multiple regression analysis, patients who had a COR-KNOT® DEVICE still had a significantly shorter operative time than control group patients, with the expected operative time for patients in the COR-KNOT® DEVICE group being about 6.5% shorter compared with patients in the control group (p = 0.022; Table 4).

- 4.

- Post-Operative Nursing: At our institution, the development of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways following surgery is developed by our nursing colleagues. After having implemented ERAS guidelines in 38 (13.7%) patients, we noticed a non-statistically significant decrease in hospital LOS when compared to no ERAS pathway (6.7 vs. 10.1 days, p = 0.174), as seen in Figure 1b.

| Outcomes | Univariate Analysis | Adjusted for Potential Risk Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | p Value | Estimate (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Hospital LOS (days) † | ||||

| PVC (yes vs. no) | −0.126 (−0.238, −0.014) | 0.028 | −0.185 (−0.340, −0.031) | 0.019 |

| Age, years | −0.002 (−0.004, 0.001) | 0.06 | 0.009 (0.004, 0.013) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | −0.083 (−0.138, −0.028) | 0.003 | 0.152 (0.031, 0.274) | 0.014 |

| EF (%) | −0.019 (−0.029, −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.013 (−0.020, −0.005) | 0.001 |

| Surgery year, years | −0.008 (−0.026, 0.011) | 0.42 | 0.004 (−0.016, 0.023) | 0.70 |

| Operation time (minutes) ‡ | ||||

| COR-KNOT® DEVICE (yes vs. no) | −0.135 (−0.182, −0.089) | <0.001 | −0.067 (−0.124, −0.010) | 0.022 |

| Female sex | −0.083 (−0.138, −0.028) | 0.003 | −0.063 (−0.114, −0.012) | 0.016 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.011 (0.006, 0.017) | <0.001 | 0.009 (0.004, 0.014) | <0.001 |

| Surgery year, years | −0.019 (−0.025, −0.014) | <0.001 | −0.013 (−0.020, −0.006) | <0.001 |

3.4. One-Year Echocardiography Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sa, M.P.B.; Van den Eynde, J.; Cavalcanti, L.R.P.; Kadyraliev, B.; Enginoev, S.; Zhigalov, K.; Ruhparwar, A.; Weymann, A.; Dreyfus, G. Mitral valve repair with minimally invasive approaches vs sternotomy: A meta-analysis of early and late results in randomized and matched observational studies. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 2307–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Onaitis, M.; Gaca, J.G.; Milano, C.A.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Glower, D. Right Minithoracotomy Versus Median Sternotomy for Mitral Valve Surgery: A Propensity Matched Study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 100, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastengren, M.; Svenarud, P.; Källner, G.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Liska, J.; Gran, I.; Dalén, M. Minimally invasive versus sternotomy mitral valve surgery when initiating a minimally invasive programme. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 58, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xi, W.; Gao, Y.; Shen, H.; Min, J.; Yang, J.; Le, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Short-term outcomes of minimally invasive mitral valve repair: A propensity-matched comparison. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 26, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia, J.L.; Cosgrove, D.M., 3rd. Minimally invasive mitral valve operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1996, 62, 1542–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzi, M.; Miceli, A.; Cerillo, A.G.; Di Stefano, G.; Kallushi, E.; Farneti, P.; Solinas, M.; Glauber, M. Training surgeons in minimally invasive mitral valve repair: A single institution experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, P.; Hassan, A.; Chitwood, W.R., Jr. Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008, 34, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonik, S.; Marchel, M.; Huczek, Z.; Kochman, J.; Wilimski, R.; Kuśmierczyk, M.; Grabowski, M.; Opolski, G.; Mazurek, T. An Individualized Approach of Multidisciplinary Heart Team for Myocardial Revascularization and Valvular Heart Disease-State of Art. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Külling, M.; Corti, R.; Noll, G.; Küest, S.; Hürlimann, D.; Wyss, C.; Reho, I.; Tanner, F.C.; Külling, J.; Meinshausen, N.; et al. Heart team approach in treatment of mitral regurgitation: Patient selection and outcome. Open Heart 2020, 7, e001280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, A.; Iafrancesco, M.; Bruno, P.; Chiariello, G.A.; Trani, C.; Burzotta, F.; Cammertoni, F.; Pasquini, A.; Diana, G.; Rosenhek, R.; et al. The multidisciplinary Heart Team approach for patients with cardiovascular disease: A step towards personalized medicine. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitlock, R.P.; Belley-Cote, E.P.; Paparella, D.; Healey, J.S.; Brady, K.; Sharma, M.; Reents, W.; Budera, P.; Baddour, A.J.; Fila, P.; et al. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion during Cardiac Surgery to Prevent Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.A.; Krajcer, Z.; Sathananthan, J.; Strickman, N.; Metzger, C.; Fearon, W.; Aziz, M.; Satler, L.F.; Waksman, R.; Eng, M.; et al. Pivotal Clinical Study to Evaluate the Safety and Effectiveness of the MANTA Percutaneous Vascular Closure Device. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e007258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.; Kim, D.; Peng, D.; Schisler, T.; Cook, R.C. Regional Anesthesia with Paravertebral Blockade Is Associated with Improved Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Minithoracotomy Cardiac Surgery. Innovations 2023, 18, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyś, M.E.; Wąsikowski, J.; Wójcik, N.; Wójcik, J.; Wasilewski, P.; Lisowski, P.; Grodzki, T. Assessment of postoperative pain management and comparison of effectiveness of pain relief treatment involving paravertebral block and thoracic epidural analgesia in patients undergoing posterolateral thoracotomy. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Valencia, M.B.; Roques, V.; Aljure, O.D. Regional analgesia for minimally invasive cardiac surgery. J. Card. Surg. 2019, 34, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harky, A.; Clarke, C.G.; Kar, A.; Bashir, M. Epidural analgesia versus paravertebral block in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 28, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ercole, F.; Arora, H.; Kumar, P.A. Paravertebral block for thoracic surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, R.G.; Myles, P.S.; Graham, J.M. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and side-effects of paravertebral vs epidural blockade for thoracotomy—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2006, 96, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.H.; Gates, S.; Naidu, B.V.; Leuwer, M.; Smith, F.G. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD009121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, D.; Gadelkarim, I.; Otto, W.; Feder, S.H.; Deshmukh, N.; Pfannmüller, B.; Misfeld, M.; Borger, M.A. Percutaneous versus open surgical cannulation for minimal invasive cardiac surgery; immediate postprocedural outcome analysis. JTCVS Tech. 2022, 16, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamelas, J.; Williams, R.F.; Mawad, M.; LaPietra, A. Complications associated with femoral cannulation during minimally invasive cardiac surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 103, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salna, M.; Takayama, H.; Garan, A.R.; Kurlansky, P.; Farr, M.A.; Colombo, P.C.; Imahiyerobo, T.; Morrissey, N.; Naka, Y.; Takeda, K. Incidence and risk factors of groin lymphocele formation after venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiogenic shock patients. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, M.; Aydin, D.M.B.; Lee, J.-S.; Schönburg, M.; Charitos, E.; Choi, Y.-H.; Liakopoulos, O.J. Femoral vessel cannulation strategies in minimally invasive cardiac surgery: Single Perclose ProGlide versus open cut-down. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 67, ezaf118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sablotzki, A.; Friedrich, I.; Mühling, J.; Dehne, M.G.; Spillner, J.; Silber, R.E.; Czeslik, E. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome following cardiac surgery: Different expression of proinflammatory cytokines and procalcitonin in patients with and without multiorgan dysfunctions. Perfusion 2002, 17, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.C.; Martin, J.; Lal, A.; Diegeler, A.; Folliguet, T.A.; Nifong, L.W.; Perier, P.; Raanani, E.; Smith, J.M.; Seeburger, J.; et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional open mitral valve surgery: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Innovations 2011, 6, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Shaw, M.; Pingle, V.; Palmer, K.; Al-Rawi, O.; Ridgway, T.; Pousios, D.; Modi, P. Use of an automated knot fastener shortens operative times in minimally invasive mitral valve repair. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2019, 101, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhala, H.; Buchan, K.; El-Shafei, H. Comparison of outcomes post Cor-Knot versus Manual tying in valve surgery: Our 8-year analysis of over 1000 patients. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 20, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanabad, A.F.; Maitland, A.; Holloway, D.D.; Adams, C.A.; Kent, W.D.T. Establishing a Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery Program. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 1739–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastengren, M.; Svenarud, P.; Källner, G.; Settergren, M.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Dalén, M. Percutaneous Vascular Closure Device in Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 110, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.A.; Brown, M.P.; Nelson, P.R.; Huber, T.S. Total percutaneous access for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (“Preclose” technique). J. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 45, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, M.M.; Ho, Y.H.; Rozen, W.M. The prone position during surgery and its complications: A systematic review and evidence-based guidelines. Int. Surg. 2015, 100, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelman, D.T.; Ali, W.B.; Williams, J.B.; Perrault, L.P.; Reddy, V.S.; Arora, R.C.; Roselli, E.E.; Khoynezhad, A.; Gerdisch, M.; Levy, J.H.; et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Cardiac Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society Recommendations. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goecke, S.; Pitts, L.; Dini, M.; Montagner, M.; Wert, L.; Akansel, S.; Kofler, M.; Stoppe, C.; Ott, S.; Jacobs, S.; et al. Enhanced Recovery After Cardiac Surgery for Minimally Invasive Valve Surgery: A Systematic Review of Key Elements and Advancements. Medicina 2025, 61, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Summary (Total n = 278) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 62.0 (54.0–71.0) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 204 (73.3) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.6 (±4.4) |

| EF%, mean (SD) | 58.0 (±7.5) |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 113 (40.6) |

| Endocarditis, n (%) | 21 (7.6) |

| Lung disease, n (%) | 34 (12.2) |

| On immunosuppression, n (%) | 7 (2.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 10 (3.6) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 8 (2.9) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Previous valve surgery, n (%) | 4 (1.4) |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 16 (5.8) |

| Previous MI, 10 (%) | 5 (1.8) |

| Angina, n (%) | 49 (17.6) |

| Heart failure (NYHA Class), n (%) | 256 (92.1) |

| Type I | 66 (25.8) |

| Type II | 111 (43.3) |

| Type III | 59 (23.1) |

| Type IV | 20 (7.8) |

| Resuscitation, n (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | 79 (28.4) |

| Inotropes, n (%) | 187 (67.3) |

| Variables | Summary (Total n = 278) |

|---|---|

| Aortic stenosis, n (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Mitral stenosis, n (%) | 18 (6.5) |

| Aortic insufficiency, n (%) | 40 (14.4) |

| Mild | 38 (32.5) |

| Moderate | 2 (5.0) |

| Moderate-Severe | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) |

| Mitral regurgitation, n (%) | 277 (99.6) |

| Mild | 3 (1.1) |

| Moderate | 10 (3.6) |

| Moderate-Severe | 46 (16.6) |

| Severe | 218 (78.7) |

| Tricuspid regurgitation, n (%) | 243 (87.4) |

| Mild | 198 (71.2) |

| Moderate | 41 (16.9) |

| Moderate-Severe | 2 (0.8) |

| Severe | 2 (0.8) |

| Procedure status, n (%) | |

| Elective | 246 (88.5) |

| Urgent | 32 (11.5) |

| Operation duration in minutes, median (IQR) | 299.0 (266.0–340.0) |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass, median (IQR) | 175.5 (148.4–199.3) |

| Aortic cross clamp, median (IQR) | 126.5 (105.8–153.3) |

| Repair type, n (%) | |

| Neochord use | 100 (41.0) |

| Isolated P2 repair | 94 (38.5) |

| Anterior leaflet repair | 16 (6.6) |

| Commissure repair | 16 (6.6) |

| Ring annuloplasty | |

| CE Physio II | 232 (95.1) |

| St. Jude Seguin | 9 (3.7) |

| No ring | 3 (1.2) |

| PVC use, n (%) | |

| No | 143 (51.4) |

| Yes | 135 (48.6) |

| ERAS, n (%) | |

| No | 240 (86.3) |

| Yes | 38 (13.7) |

| COR-KNOT® DEVICE, n (%) | |

| No | 146 (52.5) |

| Yes | 132 (47.5) |

| Percutaneous cannulation, n (%) | |

| No | 178 (64.0) |

| Yes | 100 (36.0) |

| Variables | Summary (Total n = 278) |

|---|---|

| Acute Renal Failure, n (%) | 9 (3.2) |

| Reoperation for Bleeding, n (%) | 6 (2.2) |

| Major Wound Infection, n (%) | 3 (1.1) |

| Cerebrovascular Accidents, n (%) | 2 (0.7) |

| Red Blood Cell Transfusion, n (%) | 33 (11.9) |

| Lymphocele, n (%) | 11 (4.0) |

| Post-operative Mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.4) |

| Operation time, median (IQR) | 299.0 (266.0, 340.0) |

| Hospital Length of Stay in days, median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0–7.0) |

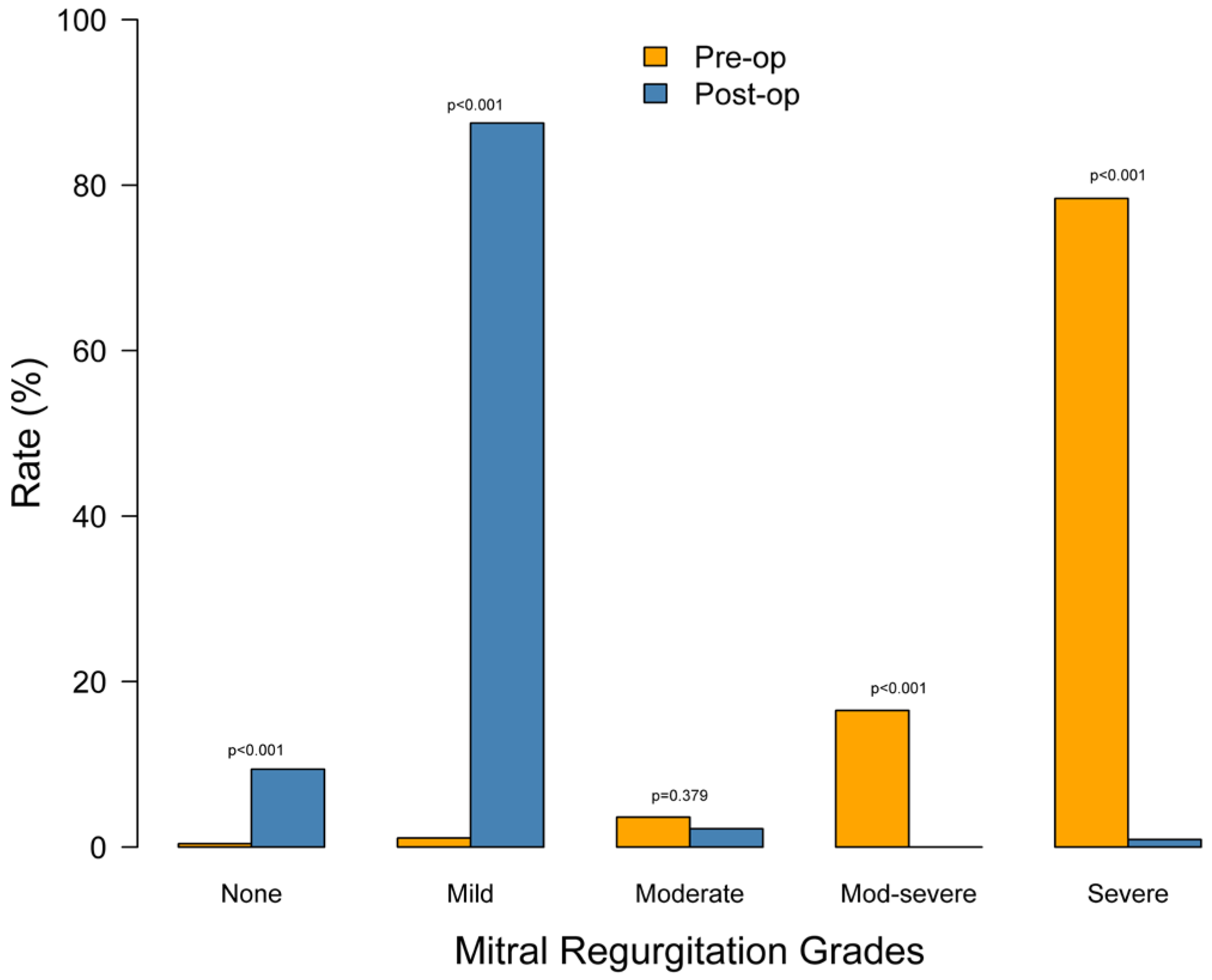

| Grade | Pre-Op (n = 278) | Post-Op (n = 224) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1 (0.4%) | 21 (9.4%) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 3 (1.1%) | 196 (87.5%) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 10 (3.6%) | 5 (2.2%) | 0.379 |

| Moderate-severe | 46 (16.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 |

| Severe | 218 (78.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mourad, N.; Al-Hakim, D.; Groenewoud, R.; Al-Zeer, B.; Wu, N.; Myring, A.; Nakahara, J.; Wood, D.; Schisler, T.; Cook, R.C. Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Using a Multidisciplinary Team Approach: A Single-Center Experience. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010044

Mourad N, Al-Hakim D, Groenewoud R, Al-Zeer B, Wu N, Myring A, Nakahara J, Wood D, Schisler T, Cook RC. Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Using a Multidisciplinary Team Approach: A Single-Center Experience. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMourad, Nicolas, Durr Al-Hakim, Rosalind Groenewoud, Bader Al-Zeer, Neil Wu, Amy Myring, Julie Nakahara, David Wood, Travis Schisler, and Richard C. Cook. 2026. "Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Using a Multidisciplinary Team Approach: A Single-Center Experience" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010044

APA StyleMourad, N., Al-Hakim, D., Groenewoud, R., Al-Zeer, B., Wu, N., Myring, A., Nakahara, J., Wood, D., Schisler, T., & Cook, R. C. (2026). Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery Using a Multidisciplinary Team Approach: A Single-Center Experience. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010044