Key Determinants Influencing Treatment Decision-Making for and Adherence to Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

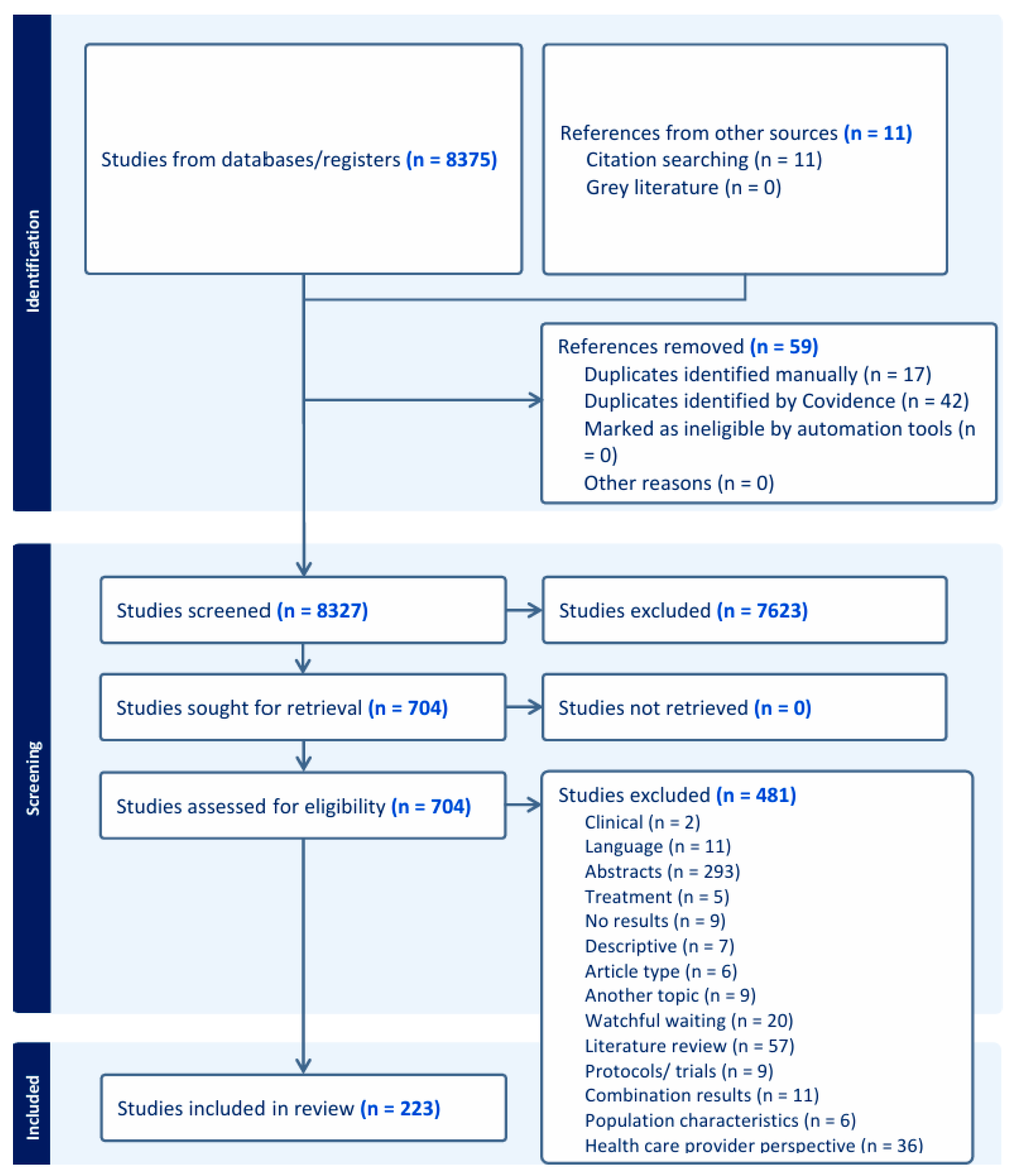

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Quality Appraisal

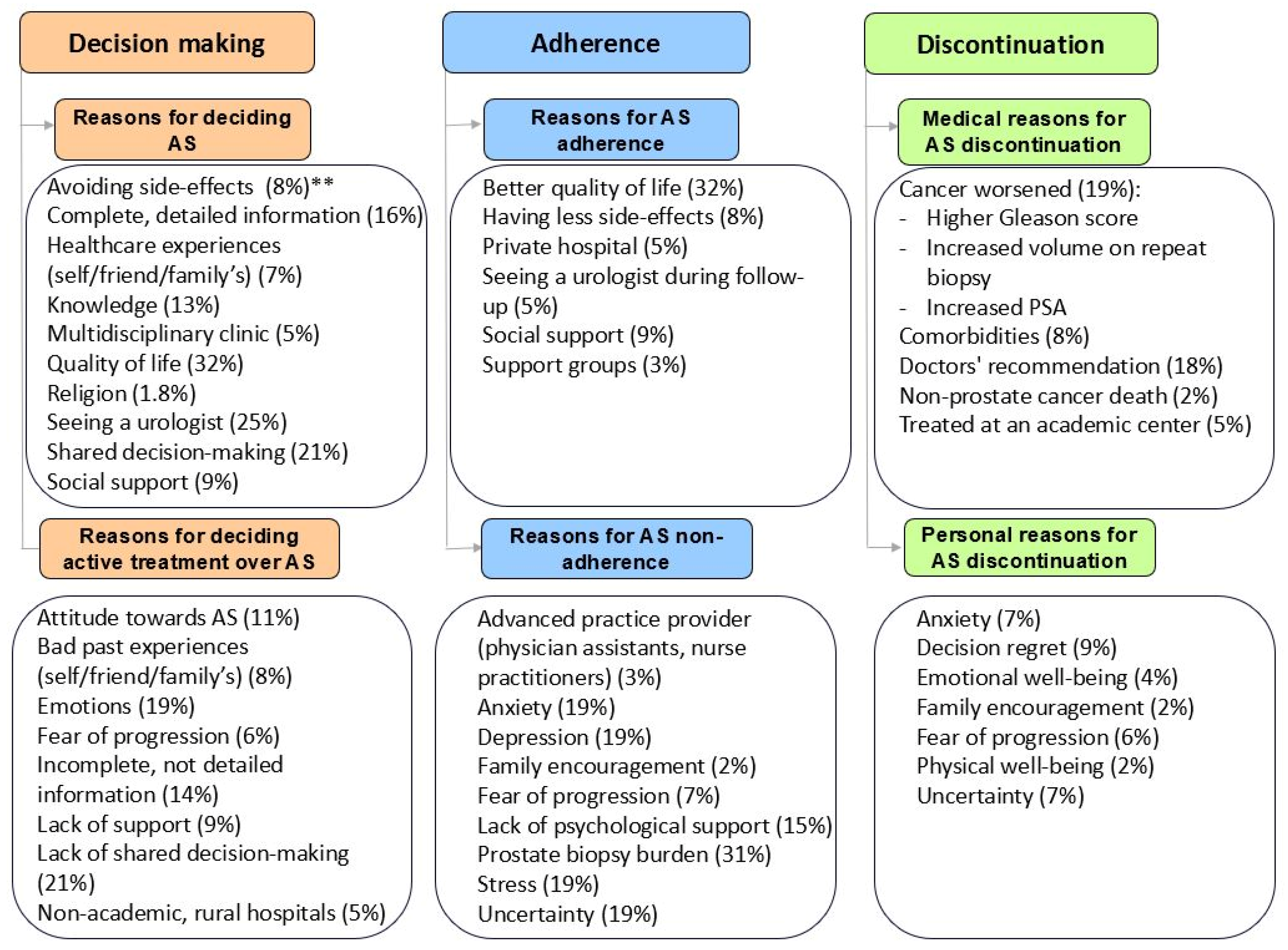

3.2. Decision-Making

3.2.1. Clinical Factors

3.2.2. Patient Factors

3.2.3. Social Factors

3.3. Adherence

3.3.1. Clinical Factors

3.3.2. Patient Factors

3.3.3. Social Factors

3.4. Discontinuation

3.4.1. Clinical Factors

3.4.2. Patient Factors

3.4.3. Social Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| RP | Radical prostatectomy |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| AS | Active surveillance |

| AT | Active treatment |

| DRE | Digital rectal examination |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| AM | Active monitoring |

| WW | Watchful waiting |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| ICTRP | International Clinical Trials Registry Platform |

| MMAT | Mixed methods appraisal tool |

| MUSIC | Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative registry |

| APP | Advanced practice providers |

| TDM | Treatment decision-making |

Appendix A

| Database Searched | Platform | Years of Coverage | Records | Records After Duplicates Removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medline ALL | Ovid | 1946–Present | 3427 | 3422 |

| Embase | Embase.com | 1971–Present | 6898 | 3778 |

| Web of Science Core Collection * | Web of Knowledge | 1975–Present | 4069 | 950 |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials | Wiley | 1992–Present | 576 | 171 |

| Additional Search Engines: Google Scholar ** | 200 | 54 | ||

| Total | 15,170 | 8375 | ||

References

- Keyes, M.; Crook, J.; Morton, G.; Vigneault, E.; Usmani, N.; Morris, W.J. Treatment options for localized prostate cancer. Can. Fam. Physician 2013, 59, 1269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.L.; Luta, G.; Hoffman, R.M.; Davis, K.M.; Lobo, T.; Zhou, Y.; Leimpeter, A.; Shan, J.; E Jensen, R.; Aaronson, D.S.; et al. Quality of life among men with low-risk prostate cancer during the first year following diagnosis: The PREPARE prospective cohort study. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, H.B. Management of low (favourable)-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangma, C.H.; Roemeling, S.; Schröder, F.H. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of early detected prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2007, 25, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizer, A.A.; Gu, X.; Chen, M.-H.; Choueiri, T.K.; Martin, N.E.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Hyatt, A.S.; Graham, P.L.; Trinh, Q.-D.; Hu, J.C.; et al. Cost Implications and Complications of Overtreatment of Low-Risk Prostate Cancer in the United States. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2015, 13, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draisma, G.; Boer, R.; Otto, S.J.; van der Cruijsen, I.W.; Damhuis, R.A.M.; Schröder, F.H.; de Koning, H.J. Lead Times and Overdetection Due to Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening: Estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bul, M.; Bergh, R.C.N.v.D.; Zhu, X.; Rannikko, A.; Vasarainen, H.; Bangma, C.H.; Schröder, F.H.; Roobol, M.J. Outcomes of initially expectantly managed patients with low or intermediate risk screen-detected localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 1672–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shill, D.K.; Roobol, M.J.; Ehdaie, B.; Vickers, A.J.; Carlsson, S.V. Active surveillance for prostate cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 2809–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, L.P.; Alberts, A.R.; Rannikko, A.; Valdagni, R.; Pickles, T.; Kakehi, Y.; Bangma, C.H.; Roobol, M.J. Compliance Rates with the Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance (PRIAS) Protocol and Disease Reclassification in Noncompliers. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeterik, T.F.; van Melick, H.H.; Dijksman, L.M.; Biesma, D.H.; Witjes, J.A.; van Basten, J.-P.A. Follow-up in Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: Strict Protocol Adherence Remains Important for PRIAS-ineligible Patients. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, R.C.N.; van Leeuwen, P.J. Adherence to Active Surveillance Protocols: Well Meant but Overconcerned? Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 202–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, R.C.N.v.D.; Essink-Bot, M.; Roobol, M.J.; Wolters, T.; Schröder, F.H.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W. Anxiety and distress during active surveillance for early prostate cancer. Cancer 2009, 115, 3868–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Sugimoto, M. Quality of life in active surveillance for early prostate cancer. Int. J. Urol. 2020, 27, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardas, M.; Liew, M.; Van den Bergh, R.C.; De Santis, M.; Bellmunt, J.; Van den Broeck, T.; Cornford, P.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; Fossati, N.; Gross, T.; et al. Quality of Life Outcomes after Primary Treatment for Clinically Localised Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellardita, L.; Valdagni, R.; Bergh, R.v.D.; Randsdorp, H.; Repetto, C.; Venderbos, L.D.; Lane, J.A.; Korfage, I.J. How Does Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer Affect Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hemelrijck, M.; Ji, X.; Helleman, J.; Roobol, M.J.; van der Linden, W.; Nieboer, D.; Bangma, C.H.; Frydenberg, M.; Rannikko, A.; Lee, L.S.; et al. Reasons for Discontinuing Active Surveillance: Assessment of 21 Centres in 12 Countries in the Movember GAP3 Consortium. Eur. Urol. 2018, 75, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, L.P.; Valdagni, R.; Rannikko, A.; Kakehi, Y.; Pickles, T.; Bangma, C.H.; Roobol, M.J. A Decade of Active Surveillance in the PRIAS Study: An Update and Evaluation of the Criteria Used to Recommend a Switch to Active Treatment. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella, N.; Beckmann, K.; Cahill, D.; Elhage, O.; Popert, R.; Cathcart, P.; Challacombe, B.; Brown, C.; Van Hemelrijck, M. A Single Educational Seminar Increases Confidence and Decreases Dropout from Active Surveillance by 5 Years After Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.; Opozda, M.J.; O’cAllaghan, M.; Vincent, A.D.; Galvão, D.A.; Short, C.E. Why do men with prostate cancer discontinue active surveillance for definitive treatment? A mixed methods investigation. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboudjian, M.; Breda, A.; Rajwa, P.; Gallioli, A.; Gondran-Tellier, B.; Sanguedolce, F.; Verri, P.; Diana, P.; Territo, A.; Bastide, C.; et al. Active Surveillance for Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Metaregression. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Folkvaljon, Y.; Curnyn, C.; Robinson, D.; Bratt, O.; Stattin, P. Uptake of Active Surveillance for Very-Low-Risk Prostate Cancer in Sweden. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Lobo, T.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Davis, K.M.; Luta, G.; Leimpeter, A.D.; Aaronson, D.; Penson, D.F.; Taylor, K. Selecting Active Surveillance: Decision Making Factors for Men with a Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. Med. Decis. Mak. 2019, 39, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collée, G.E.; van der Wilk, B.J.; van Lanschot, J.J.B.; Busschbach, J.J.; Timmermans, L.; Lagarde, S.M.; Kranenburg, L.W. Interventions that Facilitate Shared Decision-Making in Cancers with Active Surveillance as Treatment Option: A Systematic Review of Literature. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, F.B.; Roder, M.A.; Hvarness, H.; Iversen, P.; Brasso, K. Active surveillance can reduce overtreatment in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. Dan. Med. J. 2013, 60, A4575. [Google Scholar]

- Venderbos, L.D.F.; Aluwini, S.; Roobol, M.J.; Bokhorst, L.P.; Oomens, E.H.G.M.; Bangma, C.H.; Korfage, I.J. Long-term follow-up after active surveillance or curative treatment: Quality-of-life outcomes of men with low-risk prostate cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, N.; Stattin, P.; Cahill, D.; Brown, C.; Bill-Axelson, A.; Bratt, O.; Carlsson, S.; Van Hemelrijck, M. Factors Influencing Men’s Choice of and Adherence to Active Surveillance for Low-risk Prostate Cancer: A Mixed-method Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2018, 74, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.; Opozda, M.J.; Evans, H.; Finlay, A.; Galvão, D.A.; Chambers, S.K.; Short, C.E. A systematic review of the unmet supportive care needs of men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 2307–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, J.; Beirne, P.V.; Walsh, E.; Comber, H.; Fitzgerald, T.; Wallace Kazer, M. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2, CD006590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W. Publish or Perish. 2007. Available online: https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’cAthain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizer, A.A.; Paly, J.J.; Zietman, A.L.; Nguyen, P.L.; Beard, C.J.; Rao, S.K.; Kaplan, I.D.; Niemierko, A.; Hirsch, M.S.; Wu, C.-L.; et al. Models of Care and NCCN Guideline Adherence in Very-Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awamlh, B.A.H.A.; Wallis, C.J.D.; Diehl, C.; Barocas, D.A.; Beskow, L.M. The lived experience of prostate cancer: 10-year survivor perspectives following contemporary treatment of localized prostate cancer. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 18, 1370–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hussein Al Awamlh, B.; Ma, X.; Scherr, D.; Hu, J.C.; Shoag, J.E. Temporal Changes in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Men with Prostate Cancer Electing for Conservative Management in the United States. Urology 2020, 137, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvisi, M.F.; Dordoni, P.; Rancati, T.; Avuzzi, B.; Nicolai, N.; Badenchini, F.; De Luca, L.; Magnani, T.; Marenghi, C.; Menichetti, J.; et al. Supporting Patients with Untreated Prostate Cancer on Active Surveillance: What Causes an Increase in Anxiety During the First 10 Months? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandadas, C.N.; Clarke, N.W.; Davidson, S.E.; O’Reilly, P.H.; Logue, J.P.; Gilmore, L.; Swindell, R.; Brough, R.J.; Wemyss-Holden, G.D.; Lau, M.W.; et al. Early prostate cancer—Which treatment do men prefer and why? BJU Int. 2011, 107, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Burney, S.; Brooker, J.E.; Ricciardelli, L.A.; Fletcher, J.M.; Satasivam, P.; Frydenberg, M. Anxiety in the management of localised prostate cancer by active surveillance. BJU Int. 2014, 114, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.M.; Gu, L.; Oyekunle, T.; De Hoedt, A.M.; Wiggins, E.; Gay, C.J.; Lu, D.J.; Daskivich, T.J.; Freedland, S.J.; Zumsteg, Z.S.; et al. Lifestyle and sociodemographic factors associated with treatment choice of clinically localized prostate cancer in an equal access healthcare system. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022, 25, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansmann, L.; Winter, N.; Ernstmann, N.; Heidenreich, A.; Weissbach, L.; Herden, J. Health-related quality of life in active surveillance and radical prostatectomy for low-risk prostate cancer: A prospective observational study (HAROW—Hormonal therapy, Active Surveillance, Radiation, Operation, Watchful Waiting). BJU Int. 2018, 122, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, N.; Schrage, T.; Hartmann, A.; Baba, K.; Wuensch, A.; Schultze-Seemann, W.; Weis, J.; Joos, A. Mental distress and need for psychosocial support in prostate cancer patients: An observational cross-sectional study. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2020, 56, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, J.S.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Cullen, J.; Wolff, E.M.; Levie, K.E.; Rosner, I.L.; Brand, T.C.; L’esperance, J.O.; Sterbis, J.R.; Porter, C.R. A prospective study of health-related quality-of-life outcomes for patients with low-risk prostate cancer managed by active surveillance or radiation therapy. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2017, 35, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, D.A.; Alvarez, J.; Resnick, M.J.; Koyama, T.; Hoffman, K.E.; Tyson, M.D.; Conwill, R.; McCollum, D.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Goodman, M.; et al. Association Between Radiation Therapy, Surgery, or Observation for Localized Prostate Cancer and Patient-Reported Outcomes After 3 Years. JAMA 2017, 317, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, R.; Usinger, D.S.; Chen, R.C.; Shen, X. Patient Decision-Making Factors in Aggressive Treatment of Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022, 6, pkac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckmann, K.; Cahill, D.; Brown, C.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Kinsella, N. Understanding reasons for non-adherence to active surveillance for low-intermediate risk prostate cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 2728–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, K.; Cahill, D.; Brown, C.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Kinsella, N. Developing a consensus statement for psychosocial support in active surveillance for prostate cancer. BJUI Compass 2022, 4, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, K.; Kinsella, N.; Olsson, H.; Lantz, A.W.; Nordstrom, T.; Aly, M.; Adolfsson, J.; Eklund, M.; Van Hemelrijck, M. Is there any association between prostate-specific antigen screening frequency and uptake of active surveillance in men with low or very low risk prostate cancer? BMC Urol. 2019, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellardita, L.; Rancati, T.; Alvisi, M.F.; Villani, D.; Magnani, T.; Marenghi, C.; Nicolai, N.; Procopio, G.; Villa, S.; Salvioni, R.; et al. Predictors of Health-related Quality of Life and Adjustment to Prostate Cancer During Active Surveillance. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellardita, L.; Villa, S.; de Luca, L.; Donegani, S.; Magnani, T.; Salvioni, R.; Valdagni, R. Treatment decision-making process of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer: The role of multidisciplinary approach in patient engagement. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bergengren, O.; Garmo, H.; Bratt, O.; Holmberg, L.; Johansson, E.; Bill-Axelson, A. Satisfaction with Care Among Men with Localised Prostate Cancer: A Nationwide Population-based Study. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2018, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergengren, O.; Kaihola, H.; Borgefeldt, A.-C.; Johansson, E.; Garmo, H.; Bill-Axelson, A. Satisfaction with Nurse-led Follow-up in Prostate Cancer Patients—A Nationwide Population-based Study. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 38, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergengren, O.; Garmo, H.; Bratt, O.; Holmberg, L.; Johansson, E.; Bill-Axelson, A. Determinants for choosing and adhering to active surveillance for localised prostate cancer: A nationwide population-based study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e033944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Z.D.; Yeh, J.C.; Carter, H.B.; Pollack, C.E. Characteristics and Experiences of Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer Who Left an Active Surveillance Program. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2014, 7, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, A.; Ramotar, M.; Santiago, A.T.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Wolinsky, H.; Wallis, C.J.D.; Chua, M.L.K.; Paner, G.P.; van der Kwast, T.; et al. The influence of the “cancer” label on perceptions and management decisions for low-grade prostate cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, D.L.; Hong, F.; Blonquist, T.M.; Halpenny, B.; Xiong, N.; Filson, C.P.; Master, V.A.; Sanda, M.G.; Chang, P.; Chien, G.W.; et al. Decision regret, adverse outcomes, and treatment choice in men with localized prostate cancer: Results from a multi-site randomized trial. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 493.e9–493.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boberg, E.W.; Gustafson, D.H.; Hawkins, R.P.; Offord, K.P.; Koch, C.; Wen, K.-Y.; Kreutz, K.; Salner, A. Assessing the unmet information, support and care delivery needs of men with prostate cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2003, 49, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, L.P.; Lepistö, I.; Kakehi, Y.; Bangma, C.H.; Pickles, T.; Valdagni, R.; Alberts, A.R.; Semjonow, A.; Strölin, P.; Montesino, M.F.; et al. Complications after prostate biopsies in men on active surveillance and its effects on receiving further biopsies in the Prostate cancer Research International: Active Surveillance (PRIAS) study. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, J.L.; Halpenny, B.; Berry, D.L. Personal preferences and discordant prostate cancer treatment choice in an intervention trial of men newly diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, K.; Ahallal, Y.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Ghoneim, T.; Esteban, M.D.; Mulhall, J.; Vickers, A.; Eastham, J.; Scardino, P.T.; Touijer, K.A. Effect of Repeated Prostate Biopsies on Erectile Function in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2013, 191, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broughman, J.R.; Basak, R.; Nielsen, M.E.; Reeve, B.B.; Usinger, D.S.; Spearman, K.C.; Godley, P.A.; Chen, R.C. Prostate Cancer Patient Characteristics Associated with a Strong Preference to Preserve Sexual Function and Receipt of Active Surveillance. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnet, K.L.; Parker, C.; Dearnaley, D.; Brewin, C.R.; Watson, M. Does active surveillance for men with localized prostate cancer carry psychological morbidity? BJU Int. 2007, 100, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.F.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Levie, K.E.; Caumont, F.; Brand, T.C.; Rosner, I.L.; Stroup, S.; Musser, J.E.; Cullen, J.; Porter, C.R. Impact of Subsequent Biopsies on Comprehensive Health Related Quality of Life in Patients with and without Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.S.; Loeb, S.; Cole, A.P.; Zaslowe-Dude, C.; Muralidhar, V.; Kim, D.W.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Trinh, Q.-D.; Nguyen, P.L.; Mahal, B.A. United States trends in active surveillance or watchful waiting across patient socioeconomic status from 2010 to 2015. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, S.V.; Clauss, C.; Benfante, N.; Manasia, M.; Sollazzo, T.; Lynch, J.; Frank, J.; Quadri, S.; Lin, X.; Vickers, A.J.; et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance Followup Visits. Urol. Pract. 2021, 8, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.C.; Basak, R.; Meyer, A.-M.; Kuo, T.-M.; Carpenter, W.R.; Agans, R.P.; Broughman, J.R.; Reeve, B.B.; Nielsen, M.E.; Usinger, D.S.; et al. Association Between Choice of Radical Prostatectomy, External Beam Radiotherapy, Brachytherapy, or Active Surveillance and Patient-Reported Quality of Life Among Men with Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2017, 317, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.C.; Prime, S.G.; Basak, R.; Moon, D.H.; Liang, C.; Usinger, D.S.; Katz, A.J. Receipt of Guideline-Recommended Surveillance in a Population-Based Cohort of Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Active Surveillance. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 110, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, C.; Chuang, C.; Liu, K.; Li, C.; Liu, H. Changes in decisional conflict and decisional regret in patients with localised prostate cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.G.; Kim, B.J.; Slezak, J.; Harrison, T.N.; Gelfond, J.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Chien, G.W. The effect of urologist experience on choosing active surveillance for prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2015, 33, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.B.; Lin, X.; Gmelich, C.; Vertosick, E.A.; Vickers, A.J.; Manasia, M.K.; Wolchasty, N.C.; Scardino, P.T.; Eastham, J.A.; Laudone, V.P.; et al. Assessing Quality and Safety of an Advanced Practice Provider-Led Active Surveillance Clinic for Men with Prostate Cancer. Urol. Pract. 2021, 8, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, J.W.; Love, A.W.; Dunai, J.V.; Duchesne, G.M.; Bloch, S.; Costello, A.J.; Kissane, D.W. The psychological aftermath of prostate cancer treatment choices: A comparison of depression, anxiety and quality of life outcomes over the 12 months following diagnosis. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, S86–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, R.T.; Remmers, S.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Helleman, J.; Nieboer, D.; Roobol, M.J.; Venderbos, L.D.F. Movember Foundation’s Global Action Plan Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance (GAP3) consortium Using the Movember Foundation’s GAP3 cohort to measure the effect of active surveillance on patient-reported urinary and sexual function—A retrospective study in low-risk prostate cancer patients. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 2719–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, M.; Lamers, R.E.D.; Cornel, E.B.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; de Vries, M.; Kil, P.J.M. The impact of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment decision-making on health-related quality of life before treatment onset. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, M.; Lamers, R.E.D.; Kil, P.J.M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; de Vries, M. Impact of a web-based prostate cancer treatment decision aid on patient-reported decision process parameters: Results from the Prostate Cancer Patient Centered Care trial. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3739–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daubenmier, J.J.; Weidner, G.; Marlin, R.; Crutchfield, L.; Dunn-Emke, S.; Chi, C.; Gao, B.; Carroll, P.; Ornish, D. Lifestyle and health-related quality of life of men with prostate cancer managed with active surveillance. Urology 2006, 67, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, B.J.; Breckon, E.N. Impact of Health Information-Seeking Behavior and Personal Factors on Preferred Role in Treatment Decision Making in Men with Newly Diagnosed Prostate Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, B.J.; Goldenberg, S.L. Patient acceptance of active surveillance as a treatment option for low-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, B.J.; Breckon, E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information preferences of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bekker-Grob, E.W.; Bliemer, M.C.J.; Donkers, B.; Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Korfage, I.J.; Roobol, M.J.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W. Patients’ and urologists’ preferences for prostate cancer treatment: A discrete choice experiment. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donachie, K.; Adriaansen, M.; Nieuwboer, M.; Cornel, E.; Bakker, E.; Lechner, L. Selecting interventions for a psychosocial support program for prostate cancer patients undergoing active surveillance: A modified Delphi study. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 2132–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donachie, K.; Cornel, E.; Adriaansen, M.; Mennes, R.; van Oort, I.; Bakker, E.; Lechner, L. Optimizing psychosocial support in prostate cancer patients during active surveillance. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 2020, 14, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.L.; Hamdy, F.C.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Walsh, E.; Blazeby, J.M.; Peters, T.J.; Holding, P.; Bonnington, S.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordoni, P.; Badenchini, F.; Alvisi, M.F.; Menichetti, J.; De Luca, L.; Di Florio, T.; Magnani, T.; Marenghi, C.; Rancati, T.; Valdagni, R.; et al. How do prostate cancer patients navigate the active surveillance journey? A 3-year longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordoni, P.; Remmers, S.; Valdagni, R.; Bellardita, L.; De Luca, L.; Badenchini, F.; Marenghi, C.; Roobol, M.J.; Venderbos, L.D.F. Cross-cultural differences in men on active surveillance’ anxiety: A longitudinal comparison between Italian and Dutch patients from the Prostate cancer Research International Active Surveillance study. BMC Urol. 2022, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, S.J.; Calopedos, R.J.; O’cOnnell, D.L.; Chambers, S.K.; Woo, H.H.; Smith, D.P. Long-term Psychological and Quality-of-life Effects of Active Surveillance and Watchful Waiting After Diagnosis of Low-risk Localised Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Haouly, A.; Dragomir, A.; El-Rami, H.; Liandier, F.; Lacasse, A. Treatment decision-making in men with localized prostate cancer living in remote area: A cross-sectional observational study. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 15, E160–E168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eredics, K.; Dorfinger, K.; Kramer, G.; Ponholzer, A.; Madersbacher, S. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in Austria: The online registry of the Qualitätspartnerschaft Urologie (QuapU). Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2017, 129, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erim, D.O.; Bennett, A.V.; Gaynes, B.N.; Basak, R.S.; Usinger, D.; Chen, R.C. Associations between prostate cancer-related anxiety and health-related quality of life. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 4467–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernstmann, N.; Ommen, O.; Kowalski, C.; Neumann, M.; Visser, A.; Pfaff, H.; Weissbach, L. A longitudinal study of changes in provider–patient interaction in treatment of localized prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Evans, M.; Millar, J.L.; Earnest, A.; Frydenberg, M.; Davis, I.D.; Murphy, D.G.; Kearns, P.A.; Evans, S.M. Active surveillance of men with low risk prostate cancer: Evidence from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Registry–Victoria. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eymech, O.; Brunckhorst, O.; Fox, L.; Jawaid, A.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Stewart, R.; Dasgupta, P.; Ahmed, K. An exploration of wellbeing in men diagnosed with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 5459–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman-Stewart, D.; Brundage, M.D.; Nickel, J.; Mackillop, W. The information required by patients with early-stage prostate cancer in choosing their treatment. BJU Int. 2001, 87, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman-Stewart, D.; Tong, C.; Brundage, M.; Bender, J.; Robinson, J. Making their decisions for prostate cancer treatment: Patients’ experiences and preferences related to process. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 12, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filson, C.P.; Hong, F.; Xiong, N.; Pozzar, R.; Halpenny, B.; Berry, D.L. Decision support for men with prostate cancer: Concordance between treatment choice and tumor risk. Cancer 2021, 127, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.; Ouellet, V.; Pang, K.; Chevalier, S.; E Drachenberg, D.; Finelli, A.; Lattouf, J.-B.; Loiselle, C.; So, A.; Sutcliffe, S.; et al. Comparing Perspectives of Canadian Men Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer and Health Care Professionals About Active Surveillance. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, M.; Pang, K.; Ouellet, V.; Loiselle, C.; Alibhai, S.; Chevalier, S.; Drachenberg, D.E.; Finelli, A.; Lattouf, J.-B.; Sutcliffe, S.; et al. Canadian Men’s perspectives about active surveillance in prostate cancer: Need for guidance and resources. BMC Urol. 2017, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formica, M.K.; Wason, S.; Seigne, J.D.; Stewart, T.M. Impact of a decision aid on newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients’ understanding of the rationale for active surveillance. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 100, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, I.; Fagerlin, A.; Scherr, K.A.; Scherer, L.D.; Huffstetler, H.; Ubel, P.A. Gain–loss framing and patients’ decisions: A linguistic examination of information framing in physician–patient conversations. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, A.C.; Kowalkowski, M.A.; Bailey, D.E., Jr.; Kazer, M.W.; Knight, S.J.; Latini, D.M. Perception of cancer and inconsistency in medical information are associated with decisional conflict: A pilot study of men with prostate cancer who undergo active surveillance. BJU Int. 2012, 110, E50–E56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.W.; Delaney, H.; Laird, A.; Hacking, B.; Stewart, G.D.; McNeill, S.A. Consultation audio-recording reduces long-term decision regret after prostate cancer treatment: A non-randomised comparative cohort study. Surg. 2016, 14, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, M.A.; Soloway, C.T.; Eldefrawy, A.; Soloway, M.S. Factors That Influence Patient Enrollment in Active Surveillance for Low-risk Prostate Cancer. Urology 2011, 77, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, A.; Shim, J.K.; Allen, L.; Kuo, M.; Lau, K.; Loya, Z.; Brooks, J.D.; Carroll, P.R.; Cheng, I.; Chung, B.I.; et al. Factors that influence treatment decisions: A qualitative study of racially and ethnically diverse patients with low- and very-low risk prostate cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 6307–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, J.M.; Wallace, M.; Comber, H. Uncertainty and Quality of Life Among Men Undergoing Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer in the United States and Ireland. Am. J. Men’s Health 2007, 2, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, C.; Schostak, M.; Neubauer, S.; Magheli, A.; Fydrich, T.; Burkert, S.; Kendel, F. The importance of sexuality, changes in erectile functioning and its association with self-esteem in men with localized prostate cancer: Data from an observational study. BMC Urol. 2019, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, C.; Schostak, M.; Otto, I.; Kendel, F. Time pressure predicts decisional regret in men with localized prostate cancer: Data from a longitudinal multicenter study. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 3755–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J.F.; Blaschko, S.D.; Whitson, J.M.; Cowan, J.E.; Carroll, P.R. The Impact of Serial Prostate Biopsies on Sexual Function in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirama, H.; Sugimoto, M.; Miyatake, N.; Kato, T.; Venderbos, L.D.F.; Remmers, S.; Shiga, K.; Yokomizo, A.; Mitsuzuka, K.; Matsumoto, R.; et al. Health-related quality of life in Japanese low-risk prostate cancer patients choosing active surveillance: 3-year follow-up from PRIAS-JAPAN. World J. Urol. 2020, 39, 2491–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, K.E.; Niu, J.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Davis, J.W.; Kim, J.; Kuban, D.A.; Perkins, G.H.; Shah, J.B.; Smith, G.L.; et al. Physician Variation in Management of Low-Risk Prostate Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.E.; Penson, D.F.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, L.-C.; Conwill, R.; Laviana, A.A.; Joyce, D.D.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Goodman, M.; Hamilton, A.S.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Through 5 Years for Active Surveillance, Surgery, Brachytherapy, or External Beam Radiation with or Without Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2020, 323, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Lo, M.; Clark, J.A.; Albertsen, P.C.; Barry, M.J.; Goodman, M.; Penson, D.F.; Stanford, J.L.; Stroup, A.M.; Hamilton, A.S. Treatment Decision Regret Among Long-Term Survivors of Localized Prostate Cancer: Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2306–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Davis, K.M.; Lobo, T.; Luta, G.; Shan, J.; Aaronson, D.; Penson, D.F.; Leimpeter, A.D.; Taylor, K.L. Decision-making processes among men with low-risk prostate cancer: A survey study. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogden, A.; Churruca, K.; Rapport, F.; Gillatt, D. Appraising risk in active surveillance of localized prostate cancer. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmboe, E.S.; Concato, J. Treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, D.; Ruan, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, G.; Gao, Y.; Xu, D.; Na, R. Socioeconomic determinants are associated with the utilization and outcomes of active surveillance or watchful waiting in favorable-risk prostate cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9868–9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, J.; Maatz, P.; Muck, T.; Keck, B.; Friederich, H.-C.; Herzog, W.; Ihrig, A. The effect of an online support group on patients’ treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer: An online survey. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2017, 35, 37.e19–37.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, S.; Kassianos, A.P.; Everitt, H.A.; Stuart, B.; Band, R. Planning and developing a web-based intervention for active surveillance in prostate cancer: An integrated self-care programme for managing psychological distress. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntley, J.H.; Coley, R.Y.; Carter, H.B.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Krakow, M.; Pollack, C.E. Clinical Evaluation of an Individualized Risk Prediction Tool for Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Urology 2018, 121, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, L.M.; Cullen, J.; Elsamanoudi, S.; Kim, D.J.; Hudak, J.; Colston, M.; Travis, J.; Kuo, H.-C.; Porter, C.R.; Rosner, I.L. A prospective cohort study of treatment decision-making for prostate cancer following participation in a multidisciplinary clinic. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2016, 34, 233.e17–233.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, L.M.; Cullen, J.; Kim, D.J.; Elsamanoudi, S.; Hudak, J.; Colston, M.; Travis, J.; Kuo, H.; Rice, K.R.; Porter, C.R.; et al. Longitudinal regret after treatment for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 4252–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isebaert, S.; Van Audenhove, C.; Haustermans, K.; Junius, S.; Joniau, S.; De Ridder, K.; Van Poppel, H. Evaluating a Decision Aid for Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer in Clinical Practice. Urol. Int. 2008, 81, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T.L.; Bekelman, J.E.; Liu, Y.; Bach, P.B.; Basch, E.M.; Elkin, E.B.; Zelefsky, M.J.; Scardino, P.T.; Begg, C.B.; Schrag, D. Physician Visits Prior to Treatment for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeldres, C.; Cullen, J.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Wolff, E.M.; Levie, K.E.; Odem-Davis, K.; Johnston, R.B.; Pham, K.N.; Rosner, I.L.; Brand, T.C.; et al. Prospective quality-of-life outcomes for low-risk prostate cancer: Active surveillance versus radical prostatectomy. Cancer 2015, 121, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, H.J.; Thibault, G.P.; Ruttle-King, J. Perceived Stress and Quality of Life among Prostate Cancer Survivors. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapara, A.A.; Verbeek, J.F.; Nieboer, D.; Fahey, M.; Gnanapragasam, V.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Lee, L.S.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Harkin, T.; et al. Adherence to Active Surveillance Protocols for Low-risk Prostate Cancer: Results of the Movember Foundation’s Global Action Plan Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance Initiative. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 3, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, C.K.; Qureshi, M.M.; Gupta, A.; Agarwal, A.; Gignac, G.A.; Bloch, B.N.; Thoreson, N.; Hirsch, A.E. Risk factors involved in treatment delays and differences in treatment type for patients with prostate cancer by risk category in an academic safety net hospital. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 3, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-W.; Fairey Adrian, S.; Boulé Normand, G.; Field Catherine, J.; Wharton Stephanie, A.; Courneya Kerry, S. A Randomized Trial of the Effects of Exercise on Anxiety, Fear of Cancer Progression and Quality of Life in Prostate Cancer Patients on Active Surveillance. J. Urol. 2022, 207, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, D.R.; Qi, J.; Morgan, T.M.; Linsell, S.; Lane, B.R.; Montie, J.E.; Cher, M.L.; Miller, D.C. Association Between Early Confirmatory Testing and the Adoption of Active Surveillance for Men with Favorable-risk Prostate Cancer. Urology 2018, 118, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, L.; Hansen-Nord, N.S.; Osborne, R.H.; Tjønneland, A.; Hansen, R.D. Responses and relationship dynamics of men and their spouses during active surveillance for prostate cancer: Health literacy as an inquiry framework. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazer, M.W.; Bailey, D.E.; Sanda, M.; Colberg, J.; Kelly, W.K. An Internet Intervention for Management of Uncertainty During Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2011, 38, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazer, M.W.; Bailey, D.E., Jr.; Colberg, J.; Kelly, W.K.; Carroll, P. The needs for men undergoing active surveillance (AS) for prostate cancer: Results of a focus group study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.K.; Zahrieh, D.; Patel, D.; Mohler, J.L.; Chen, R.C.; Paskett, E.D.; Liu, H.; Peil, E.S.; Rock, C.L.; Hahn, O.; et al. Diet and Health-related Quality of Life Among Men on Active Surveillance for Early-stage Prostate Cancer: The Men’s Eating and Living Study (Cancer and Leukemia Group 70807 [Alliance]). Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.P.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Hoffman, R.M.; Aaronson, D.S.; Lobo, T.; Luta, G.; Leimpter, A.D.; Shan, J.; Potosky, A.L.; Taylor, K.L. Sociodemographic and Clinical Predictors of Switching to Active Treatment among a Large, Ethnically Diverse Cohort of Men with Low Risk Prostate Cancer on Observational Management. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendel, F.; Helbig, L.; Neumann, K.; Herden, J.; Stephan, C.; Schrader, M.; Gaissmaier, W. Patients’ perceptions of mortality risk for localized prostate cancer vary markedly depending on their treatment strategy. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.S.; Zhu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Newcomb, L.F.; Schenk, J.M.; Brooks, J.D.; Carroll, P.R.; Dash, A.; Ellis, W.J.; Filson, C.P.; et al. Treatment in the absence of disease reclassification among men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Cancer 2022, 128, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kord, E.; Jung, N.; Posielski, N.; Jiang, J.; Elsamanoudi, S.; Chesnut, G.T.; Speir, R.; Stroup, S.; Musser, J.; Ernest, A.; et al. Prospective Long-term Health-related Quality of Life Outcomes After Surgery, Radiotherapy, or Active Surveillance for Localized Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2023, 48, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korman, H.; Lanni, T.; Shah, C., Jr.; Parslow, J.; Tull, J.; Ghilezan, M.; Krauss, D.; Balaraman, S.; Kernen, K.; Cotant, M.; et al. Impact of a Prostate Multidisciplinary Clinic Program on Patient Treatment Decisions and on Adherence to NCCN Guidelines: The William Beaumont Hospital Experience. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 36, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, L.Y.; Shahinian, V.B.; Oerline, M.K.; Kaufman, S.R.; Skolarus, T.A.; Caram, M.E.V.; Hollenbeck, B.K. Understanding Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e1678–e1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, R.E.; Cuypers, M.; de Vries, M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Bosch, J.R.; Kil, P.J. How do patients choose between active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy? The effect of a preference-sensitive decision aid on treatment decision making for localized prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2017, 35, 37.e9–37.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, R.E.D.; Cuypers, M.; de Vries, M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; Kil, P.J.M. Differences in treatment choices between prostate cancer patients using a decision aid and patients receiving care as usual: Results from a randomized controlled trial. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 4327–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.; Metcalfe, C.; Young, G.J.; Peters, T.J.; Blazeby, J.; Avery, K.N.L.; Dedman, D.; Down, L.; Mason, M.D.; Neal, D.E.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes in the ProtecT randomized trial of clinically localized prostate cancer treatments: Study design, and baseline urinary, bowel and sexual function and quality of life. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.A.; Donovan, J.L.; Young, G.J.; Davis, M.; Walsh, E.I.; Avery, K.N.; Blazeby, J.M.; Mason, M.D.; Martin, R.M.; Peters, T.J.; et al. Functional and quality of life outcomes of localised prostate cancer treatments (Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment [ProtecT] study). BJU Int. 2022, 130, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.F.; Tyson, M.D.; Alvarez, J.R.; Koyama, T.; Hoffman, K.E.; Resnick, M.J.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Wu, X.-C.; Chen, V.; Paddock, L.E.; et al. The Influence of Psychosocial Constructs on the Adherence to Active Surveillance for Localized Prostate Cancer in a Prospective, Population-based Cohort. Urology 2017, 103, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, D.M.; Hart, S.L.; Knight, S.J.; Cowan, J.E.; Ross, P.L.; DuChane, J.; Carroll, P.R.; CaPSURE Investigators. The Relationship Between Anxiety and Time to Treatment for Patients with Prostate Cancer on Surveillance. J. Urol. 2007, 178 Pt 1, 826–831, discussion 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.-C.L.; McFall, S.L.; Byrd, T.L.; Volk, R.J.; Cantor, S.B.; Kuban, D.A.; Mullen, P.D. Is “Active Surveillance” an Acceptable Alternative? A Qualitative Study of Couples’ Decision Making about Early-Stage, Localized Prostate Cancer. Narrat. Inq. Bioeth. 2016, 6, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwin, M.S.; Lubeck, D.P.; Spitalny, G.M.; Henning, J.M.; Carroll, P.R. Mental health in men treated for early stage prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2002, 95, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Womble, P.R.; Merdan, S.; Miller, D.C.; Montie, J.E.; Denton, B.T. Factors Influencing Selection of Active Surveillance for Localized Prostate Cancer. Urology 2015, 86, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Curnyn, C.; Fagerlin, A.; Braithwaite, R.S.; Schwartz, M.D.; Lepor, H.; Carter, H.B.; Ciprut, S.; Sedlander, E. Informational needs during active surveillance for prostate cancer: A qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Folkvaljon, Y.; Makarov, D.V.; Bratt, O.; Bill-Axelson, A.; Stattin, P. Five-year Nationwide Follow-up Study of Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Berglund, A.; Stattin, P. Population Based Study of Use and Determinants of Active Surveillance and Watchful Waiting for Low and Intermediate Risk Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 1742–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokman, U.; Vasarainen, H.; Lahdensuo, K.; Erickson, A.; Muhonen, T.; Mirtti, T.; Rannikko, A. Prospective Longitudinal Health-related Quality of Life Analysis of the Finnish Arm of the PRIAS Active Surveillance Cohort: 11 Years of Follow-up. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Wallis, C.J.D.; Huang, L.-C.; Wittmann, D.; Klaassen, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Koyama, T.; Laviana, A.A.; Conwill, R.; Goodman, M.; et al. Association between Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer and Mental Health Outcomes. J. Urol. 2022, 207, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.D.; Li, H.H.; Mader, E.M.; Stewart, T.M.; Morley, C.P.; Formica, M.K.; Perrapato, S.D.; Seigne, J.D.; Hyams, E.S.; Irwin, B.H.; et al. Cognitive and Affective Representations of Active Surveillance as a Treatment Option for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. Am. J. Men’s Health 2016, 11, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, E.M.; Li, H.H.; Lyons, K.D.; Morley, C.P.; Formica, M.K.; Perrapato, S.D.; Irwin, B.H.; Seigne, J.D.; Hyams, E.S.; Mosher, T.; et al. Qualitative insights into how men with low-risk prostate cancer choosing active surveillance negotiate stress and uncertainty. BMC Urol. 2017, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallapareddi, A.; Ruterbusch, J.; Reamer, E.; Eggly, S.; Xu, J. Active surveillance for low-risk localized prostate cancer: What do men and their partners think? Fam. Pract. 2017, 34, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenghi, C.; Alvisi, M.F.; Palorini, F.; Avuzzi, B.; Badenchini, F.; Bedini, N.; Bellardita, L.; Biasoni, D.; Bosetti, D.; Casale, A.; et al. Eleven-year Management of Prostate Cancer Patients on Active Surveillance: What have We Learned? Tumori J. 2017, 103, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin EP, S.; Corr, J.; Casey, R. Nurse-led active surveillance for prostate cancer is safe, effective and associated with high rates of patient satisfaction—Results of an audit in the East of England. Ecancermedicalscience 2018, 12, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, K.; Assel, M.; Ehdaie, B.; Vickers, A. Long-Term Cancer Specific Anxiety in Men Undergoing Active Surveillance of Prostate Cancer: Findings from a Large Prospective Cohort. J. Urol. 2018, 200, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, L.; Wilding, S.; Wagland, R.; Nayoan, J.; Rivas, C.; Downing, A.; Wright, P.; Brett, J.; Kearney, T.; Cross, W.; et al. The psychological impact of being on a monitoring pathway for localised prostate cancer: A UK-wide mixed methods study. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew, A.G.; Raz, O.; Currie, K.L.; Louis, A.S.; Jiang, H.; Davidson, T.; Fleshner, N.E.; Finelli, A.; Trachtenberg, J. Psychological distress and lifestyle disruption in low-risk prostate cancer patients: Comparison between active surveillance and radical prostatectomy. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2017, 36, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, M.J.; Abouassaly, R.; Kim, S.P.; Zhu, H. Contemporary Nationwide Patterns of Active Surveillance Use for Prostate Cancer. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1569–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McFall, S.L.; Mullen, P.D.; Byrd, T.L.; Cantor, S.B.; Le, Y.; Torres-Vigil, I.; Pettaway, C.; Volk, R.J. Treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer: A concept mapping approach. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2079–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.; Opozda, M.J.; Short, C.E.; Galvão, D.A.; Tutino, R.; Diefenbach, M.; Ehdaie, B.; Nelson, C. Social ecological influences on treatment decision-making in men diagnosed with low risk, localised prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, J.; De Luca, L.; Dordoni, P.; Donegani, S.; Marenghi, C.; Valdagni, R.; Bellardita, L. Making Active Surveillance a path towards health promotion: A qualitative study on prostate cancer patients’ perceptions of health promotion during Active Surveillance. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriel, S.W.; Hetherington, L.; Seggie, A.; Castle, J.T.; Cross, W.; Roobol, M.J.; Gnanapragasam, V.; Moore, C.M.; Prostate Cancer UK Expert Reference Group on Active Surveillance. Best practice in active surveillance for men with prostate cancer: A Prostate Cancer UK consensus statement. BJU Int. 2019, 124, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, N.; Metcalfe, C.; Ronsmans, C.; Davis, M.; Lane, J.A.; Sterne, J.A.; Peters, T.J.; Hamdy, F.C.; Neal, D.E.; Donovan, J.L. A comparison of socio-demographic and psychological factors between patients consenting to randomisation and those selecting treatment (the ProtecT study). Contemp. Clin. Trials 2006, 27, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, M.V.; Bennett, M.; Vincent, A.; Lee, O.T.; Lallas, C.D.; Trabulsi, E.J.; Gomella, L.G.; Dicker, A.P.; Showalter, T.N.; Sarkar, I.N. Identifying Barriers to Patient Acceptance of Active Surveillance: Content Analysis of Online Patient Communications. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, A.; Sommer, J.; Akerman, M.; Lischalk, J.W.; Haas, J.; Corcoran, A.; Katz, A. Four-year quality-of-life outcomes in low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients following definitive stereotactic body radiotherapy versus management with active surveillance. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.H.; Basak, R.S.; Usinger, D.S.; Dickerson, G.A.; Morris, D.E.; Perman, M.; Lim, M.; Wibbelsman, T.; Chang, J.; Crawford, Z.; et al. Patient-reported Quality of Life Following Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy and Conventionally Fractionated External Beam Radiotherapy Compared with Active Surveillance Among Men with Localized Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, L.W.; Oliffe, J.L.; Davison, B.J. Masculinities and patient perspectives of communication about active surveillance for prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, R.E.; Leader, A.E.; Censits, J.H.; Trabulsi, E.J.; Keith, S.W.; Petrich, A.M.; Quinn, A.M.; Den, R.B.; Hurwitz, M.D.; Lallas, C.D.; et al. Decision Support and Shared Decision Making About Active Surveillance Versus Active Treatment Among Men Diagnosed with Low-Risk Prostate Cancer: A Pilot Study. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naha, U.; Freedland, S.J.; Abern, M.R.; Moreira, D.M. The association of cancer-specific anxiety with disease aggressiveness in men on active surveillance of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Nielsen, M.; Møller, H.; Tjønneland, A.; Borre, M. Patient-reported outcome measures after treatment for prostate cancer: Results from the Danish Prostate Cancer Registry (DAPROCAdata). Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 64, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.B.; Spalletta, O.; Kristensen, M.A.T.; Brodersen, J. Psychosocial consequences of potential overdiagnosis in prostate cancer a qualitative interview study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2020, 38, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, R.; Næss-Andresen, T.F.; Myklebust, T.Å.; Bernklev, T.; Kersten, H.; Haug, E.S. Fear of Recurrence in Prostate Cancer Patients: A Cross-sectional Study After Radical Prostatectomy or Active Surveillance. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2021, 25, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’CAllaghan, C.; Dryden, T.; Hyatt, A.; Brooker, J.; Burney, S.; Wootten, A.C.; White, A.; Frydenberg, M.; Murphy, D.; Williams, S.; et al. ‘What is this active surveillance thing?’ Men’s and partners’ reactions to treatment decision making for prostate cancer when active surveillance is the recommended treatment option. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Davison, B.J.; Pickles, T.; Mróz, L. The Self-Management of Uncertainty Among Men Undertaking Active Surveillance for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, H.; Nordström, T.; Clements, M.; Grönberg, H.; Lantz, A.W.; Eklund, M. Intensity of Active Surveillance and Transition to Treatment in Men with Low-risk Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 3, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orom, H.; Homish, D.L.; Homish, G.G.; Underwood, W. Quality of physician-patient relationships is associated with the influence of physician treatment recommendations among patients with prostate cancer who chose active surveillance. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2014, 32, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orom, H.; Underwood, W.; Biddle, C., 3rd. Emotional Distress Increases the Likelihood of Undergoing Surgery among Men with Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, I.; Hilger, C.; Magheli, A.; Stadler, G.; Kendel, F. Illness representations, coping and anxiety among men with localized prostate cancer over an 18-months period: A parallel vs. level-contrast mediation approach. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, E.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Tomlinson, G.A.; Matthew, A.G.; Nesbitt, M.; Finelli, A.; Trachtenberg, J.; Mina, D.S. Influence of physical activity on active surveillance discontinuation in men with low-risk prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2019, 30, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.R.; Kim, S.; Stein, M.N.; Haffty, B.G.; Kim, I.Y.; Goyal, S. Trends in active surveillance for very low-risk prostate cancer: Do guidelines influence modern practice? Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 2410–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.A.; Davis, J.W.; Latini, D.M.; Baum, G.; Wang, X.; Ward, J.F.; Kuban, D.; Frank, S.J.; Lee, A.K.; Logothetis, C.J.; et al. Relationship between illness uncertainty, anxiety, fear of progression and quality of life in men with favourable-risk prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BJU Int. 2016, 117, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, R.; Ferrante, S.; Qi, J.; Dunn, R.L.; Berry, D.L.; Semerjian, A.; Brede, C.M.; George, A.K.; Lane, B.R.; Ginsburg, K.B.; et al. Patient Preferences and Treatment Decisions for Prostate Cancer: Results from A Statewide Urological Quality Improvement Collaborative. Urology 2021, 155, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, S.M.; Wang, C.-H.E.; Victorson, D.E.; Helfand, B.T.; Novakovic, K.R.; Brendler, C.B.; Albaugh, J.A. A Longitudinal Study of Predictors of Sexual Dysfunction in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Sex. Med. 2015, 3, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, K.N.; Cullen, J.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Wolff, E.M.; Levie, K.E.; Odem-Davis, K.; Banerji, J.S.; Rosner, I.L.; Brand, T.C.; L’esperance, J.O.; et al. Prospective Quality of Life in Men Choosing Active Surveillance Compared to Those Biopsied but not Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzar, R.A.; Xiong, N.; Hong, F.; Filson, C.P.; Chang, P.; Halpenny, B.; Berry, D.L. Concordance between influential adverse treatment outcomes and localized prostate cancer treatment decisions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punnen, S.; Cowan, J.E.; Dunn, L.B.; Shumay, D.M.; Carroll, P.R.; Cooperberg, M.R. A longitudinal study of anxiety, depression and distress as predictors of sexual and urinary quality of life in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013, 112, E67–E75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, A.; Grande, D.; Mitra, N.; Pollack, C.E. Which Patients Report That Their Urologists Advised Them to Forgo Initial Treatment for Prostate Cancer? Urology 2018, 115, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamer, E.; Yang, F.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Liu, J.; Xu, J. Influence of Men’s Personality and Social Support on Treatment Decision-Making for Localized Prostate Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1467056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmers, S.; Beyer, K.; Lalmahomed, T.A.; Prinsen, P.; Horevoorts, N.J.; Sibert, N.T.; Kowalski, C.; Barletta, F.; Brunckhorst, O.; Gandaglia, G.; et al. An Overview of Patient-reported Outcomes for Men with Prostate Cancer: Results from the PIONEER Consortium. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 71, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, C.; Rancati, T.; Magnani, T.; Alvisi, M.F.; Avuzzi, B.; Badenchini, F.; Marenghi, C.; Stagni, S.; Maffezzini, M.; Villa, S.; et al. “What if…”: Decisional Regret in Patients who Discontinued Active Surveillance. Tumori J. 2016, 102, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.O.; Alibhai, S.M.; Panzarella, T.; Klotz, L.; Komisarenko, M.; Fleshner, N.E.; Urbach, D.; Finelli, A. The uptake of active surveillance for the management of prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2016, 10, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossen, S.; Hansen-Nord, N.S.; Kayser, L.; Borre, M.; Borre, M.; Larsen, R.G.; Trichopoulou, A.; Boffetta, P.; Tjønneland, A.; Hansen, R.D. The Impact of Husbands’ Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Participation in a Behavioral Lifestyle Intervention on Spouses’ Lives and Relationships with Their Partners. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, E1–E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruane-McAteer, E.; Porter, S.; O’SUllivan, J.; Dempster, M.; Prue, G. Investigating the psychological impact of active surveillance or active treatment in newly diagnosed favorable-risk prostate cancer patients: A 9-month longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherr, K.A.; Fagerlin, A.; Hofer, T.; Scherer, L.D.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Williamson, L.D.; Kahn, V.C.; Montgomery, J.S.; Greene, K.L.; Zhang, B.; et al. Physician Recommendations Trump Patient Preferences in Prostate Cancer Treatment Decisions. Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 37, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarra, A.; Gentilucci, A.; Salciccia, S.; Von Heland, M.; Ricciuti, G.P.; Marzio, V.; Pierella, F.; Musio, D.; Tombolini, V.; Frantellizzi, V.; et al. Psychological and functional effect of different primary treatments for prostate cancer: A comparative prospective analysis. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2018, 36, 340.e7–340.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, A.T.; Taylor, K.L.; Davis, K.; Nepple, K.G.; Lynch, J.H.; Oberle, A.D.; Hall, I.J.; Volk, R.J.; Reisinger, H.S.; Hoffman, R.M.; et al. Why men with a low-risk prostate cancer select and stay on active surveillance: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, D.; Randazzo, M.; Leupold, U.; Zeh, N.; Isbarn, H.; Chun, F.K.; Ahyai, S.A.; Baumgartner, M.; Huber, A.; Recker, F.; et al. Protocol-based Active Surveillance for Low-risk Prostate Cancer: Anxiety Levels in Both Men and Their Partners. Urology 2012, 80, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P.R.; Maturen, K.E.; George, A.K.; Borza, T.; Ellimoottil, C.; Montgomery, J.S.; Wei, J.T.; Denton, B.T.; Davenport, M.S. Temporary Health Impact of Prostate MRI and Transrectal Prostate Biopsy in Active Surveillance Prostate Cancer Patients. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2019, 16, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J.B.; Paivanas, T.A.; Buffington, P.; Ruyle, S.R.; Cohen, E.S.; Natale, R.; Mehlhaff, B.; Suh, R.; Bradford, T.J.; Koo, A.S.; et al. Three-year Active Surveillance Outcomes in a Contemporary Community Urology Cohort in the United States. Urology 2019, 130, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidana, A.; Hernandez, D.J.; Feng, Z.; Partin, A.W.; Trock, B.J.; Saha, S.; Epstein, J.I. Treatment decision-making for localized prostate cancer: What younger men choose and why. Prostate 2012, 72, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P.; King, M.T.; Egger, S.; Berry, M.P.; Stricker, P.D.; Cozzi, P.; Ward, J.; O’Connell, D.L.; Armstrong, B.K. Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2009, 339, b4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureda, A.; Fumadó, L.; Ferrer, M.; Garín, O.; Bonet, X.; Castells, M.; Mir, M.C.; Abascal, J.M.; Vigués, F.; Cecchini, L.; et al. Health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance versus radical prostatectomy, external-beam radiotherapy, prostate brachytherapy and reference population: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sypre, D.; Pignot, G.; Touzani, R.; Marino, P.; Walz, J.; Rybikowski, S.; Maubon, T.; Branger, N.; Salem, N.; Mancini, J.; et al. Impact of active surveillance for prostate cancer on the risk of depression and anxiety. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.-J.; Marks, L.S.; Hoyt, M.A.; Kwan, L.; Filson, C.P.; Macairan, M.; Lieu, P.; Litwin, M.S.; Stanton, A.L. The Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Anxiety in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.L.; Hoffman, R.M.; Davis, K.M.; Luta, G.; Leimpeter, A.; Lobo, T.; Kelly, S.P.; Shan, J.; Aaronson, D.; Tomko, C.A.; et al. Treatment Preferences for Active Surveillance versus Active Treatment among Men with Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, F.R.; Hehakaya, C.; Meijer, R.P.; van Melick, H.H.E.; Verkooijen, H.M.; van der Voort van Zyp, J.R.N. Patient preferences for treatment modalities for localised prostate cancer. BJUI Compass 2023, 4, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurtle, D.; Jenkins, V.; Freeman, A.; Pearson, M.; Recchia, G.; Tamer, P.; Leonard, K.; Pharoah, P.; Aning, J.; Madaan, S.; et al. Clinical Impact of the Predict Prostate Risk Communication Tool in Men Newly Diagnosed with Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timilshina, N.; Komisarenko, M.; Martin, L.J.; Cheung, D.C.; Alibhai, S.; Richard, P.O.; Finelli, A. Factors Associated with Discontinuation of Active Surveillance among Men with Low-Risk Prostate Cancer: A Population-Based Study. J. Urol. 2021, 206, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruye, T.; O’CAllaghan, M.; Ettridge, K.; Jay, A.; Santoro, K.; Moretti, K.; Beckmann, K. Factors impacting on sexual function among men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Prostate 2023, 83, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruye, T.; O’cAllaghan, M.; Moretti, K.; Jay, A.; Higgs, B.; Santoro, K.; Boyle, T.; Ettridge, K.; Beckmann, K. Patient-reported functional outcome measures and treatment choice for prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2022, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todio, E.; Schofield, P.; Sharp, J. A Qualitative Study of Men’s Experiences Using Navigate: A Localized Prostate Cancer Treatment Decision Aid. MDM Policy Pract. 2023, 8, 23814683231198003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohi, Y.; Kato, T.; Matsumoto, R.; Shinohara, N.; Shiga, K.; Yokomizo, A.; Nakamura, M.; Kume, H.; Mitsuzuka, K.; Sasaki, H.; et al. The impact of complications after initial prostate biopsy on repeat protocol biopsy acceptance rate. Results from the Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance JAPAN study. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohi, Y.; Kato, T.; Yokomizo, A.; Mitsuzuka, K.; Tomida, R.; Inokuchi, J.; Matsumoto, R.; Saito, T.; Sasaki, H.; Inoue, K.; et al. Impact of health-related quality of life on repeat protocol biopsy compliance on active surveillance for favorable prostate cancer: Results from a prospective cohort in the PRIAS-JAPAN study. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2022, 40, 56.e9–56.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergh, R.C.v.D.; Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Roobol, M.J.; Schröder, F.H.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W. Do Anxiety and Distress Increase During Active Surveillance for Low Risk Prostate Cancer? J. Urol. 2010, 183, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, R.C.v.D.; Korfage, I.J.; Roobol, M.J.; Bangma, C.H.; de Koning, H.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Essink-Bot, M. Sexual function with localized prostate cancer: Active surveillance vs radical therapy. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, R.C.V.D.; Van Vugt, H.A.; Korfage, I.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Roobol, M.J.; Schröder, F.H.; Essink-Bot, M. Disease insight and treatment perception of men on active surveillance for early prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2010, 105, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Stam, M.-A.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; Kieffer, J.M.; van der Voort van Zyp, J.R.N.; Tillier, C.N.; Horenblas, S.; van der Poel, H.G. Patient-reported Outcomes Following Treatment of Localised Prostate Cancer and Their Association with Regret About Treatment Choices. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 3, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Stam, M.; van der Poel, H.G.; Zyp, J.R.v.d.V.v.; Tillier, C.N.; Horenblas, S.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bosch, J.R. The accuracy of patients’ perceptions of the risks associated with localised prostate cancer treatments. BJU Int. 2018, 121, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, H.A.; Roobol, M.J.; van der Poel, H.G.; van Muilekom, E.H.; Busstra, M.; Kil, P.; Oomens, E.H.; Leliveld, A.; Bangma, C.H.; Korfage, I.; et al. Selecting men diagnosed with prostate cancer for active surveillance using a risk calculator: A prospective impact study. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanagas, G.; Mickevičienė, A.; Ulys, A. Does quality of life of prostate cancer patients differ by stage and treatment? Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 41, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasarainen, H.; Lokman, U.; Ruutu, M.; Taari, K.; Rannikko, A. Prostate cancer active surveillance and health-related quality of life: Results of the Finnish arm of the prospective trial. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbos, L.D.; Deschamps, A.; Dowling, J.; Carl, E.-G.; van Poppel, H.; Remmers, S.; Roobol, M.J.; Uomo, A.E. Sexual Function of Men Undergoing Active Prostate Cancer Treatment Versus Active Surveillance: Results of the Europa Uomo Patient Reported Outcome Study. Oncol. Haematol. 2022, 18, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbos, L.D.F.; Remmers, S.; Deschamps, A.; Dowling, J.; Carl, E.-G.; Pereira-Azevedo, N.; Roobol, M.J. The Europa Uomo Patient Reported Outcome Study 2.0—Prostate Cancer Patient-reported Outcomes to Support Treatment Decision-making. Eur. Urol. Focus 2023, 9, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venderbos, L.D.F.; Bergh, R.C.N.v.D.; Roobol, M.J.; Schröder, F.H.; Essink-Bot, M.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Korfage, I.J. A longitudinal study on the impact of active surveillance for prostate cancer on anxiety and distress levels. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 24, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, R.J.; Kinsman, G.T.; Le, Y.-C.L.; Swank, P.; Blumenthal-Barby, J.; McFall, S.L.; Byrd, T.L.; Mullen, P.D.; Cantor, S.B. Designing Normative Messages About Active Surveillance for Men With Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.J.; McFall, S.L.; Cantor, S.B.; Byrd, T.L.; Le, Y.-C.L.; Kuban, D.A.; Mullen, P.D. ‘It’s not like you just had a heart attack’: Decision-making about active surveillance by men with localized prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, L.J.; Ho, C.K.; Donnelly, B.J.; Reuther, J.D.; Kerba, M. A population-based study examining the influence of a specialized rapid-access cancer clinic on initial treatment choice in localized prostate cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 12, E314–E317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J.; Donovan, J.; Lane, A.; Davis, M.; Walsh, E.; Neal, D.; Turner, E.; Martin, R.; Metcalfe, C.; Peters, T.; et al. Strategies adopted by men to deal with uncertainty and anxiety when following an active surveillance/monitoring protocol for localised prostate cancer and implications for care: A longitudinal qualitative study embedded within the ProtecT trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, W.; Peter, N.H.; Susan, B.; Leila, R.; Lane, J.A.; Salter, C.E.; Tilling, K.; Speakman, M.J.; Brewster, S.F.; Evans, S.; et al. Establishing nurse-led active surveillance for men with localised prostate cancer: Development and formative evaluation of a model of care in the ProtecT trial. BMJ Open. 2015, 5, e008953. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, J.; Rosario, D.J.; Howson, J.; Avery, K.N.L.; Salter, C.E.; Goodwin, M.L.; Blazeby, J.M.; Lane, J.A.; Metcalfe, C.; E Neal, D.; et al. Role of information in preparing men for transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: A qualitative study embedded in the ProtecT trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J.; Rosario, D.J.; Macefield, R.C.; Avery, K.N.; Salter, C.E.; Goodwin, M.L.; Blazeby, J.M.; Lane, J.A.; Metcalfe, C.; Neal, D.E.; et al. Psychological Impact of Prostate Biopsy: Physical Symptoms, Anxiety, and Depression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4235–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, K.; Carmona-Echeveria, L.; Kuru, T.; Gaziev, G.; Serrao, E.; Parashar, D.; Frey, J.; Dimov, I.; Seidenader, J.; Acher, P.; et al. Transperineal prostate biopsies for diagnosis of prostate cancer are well tolerated: A prospective study using patient-reported outcome measures. Asian J. Androl. 2017, 19, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagland, R.; Nayoan, J.; Matheson, L.; Rivas, C.; Brett, J.; Downing, A.; Wilding, S.; Butcher, H.; Gavin, A.; Glaser, A.W.; et al. ‘Very difficult for an ordinary guy’: Factors influencing the quality of treatment decision-making amongst men diagnosed with localised and locally advanced prostate cancer: Findings from a UK-wide mixed methods study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.M.; Santos-Iglesias, P. Sexual satisfaction in prostate cancer: A multi-group comparison study of treated patients, patients under active surveillance, patients with negative biopsy, and controls. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 18, 1790–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.J.D.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, L.-C.; Penson, D.F.; Koyama, T.; Kaplan, S.H.; Greenfield, S.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Klaassen, Z.; Conwill, R.; et al. Association of Treatment Modality, Functional Outcomes, and Baseline Characteristics With Treatment-Related Regret Among Men With Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.; Shinkins, B.; Frith, E.; Neal, D.; Hamdy, F.; Walter, F.; Weller, D.; Wilkinson, C.; Faithfull, S.; Wolstenholme, J.; et al. Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: Implications for redesigning follow-up. BJU Int. 2016, 117, E10–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Leydon, G.; Eyles, C.; Moore, C.M.; Richardson, A.; Birch, B.; Prescott, P.; Powell, C.; Lewith, G. A quantitative analysis of the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety in patients with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakoon, M.; Papa, N.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Evans, S.; Millar, J.; Frydenberg, M.; Bolton, D.; Murphy, D.G. The current use of active surveillance in an Australian cohort of men: A pattern of care analysis from the Victorian Prostate Cancer Registry. BJU Int. 2015, 115, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, C.B.; Gilbourd, D.; Louie-Johnsun, M. Anxiety and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients undergoing active surveillance of prostate cancer in an Australian centre. BJU Int. 2014, 113, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womble, P.R.; Montie, J.E.; Ye, Z.; Linsell, S.M.; Lane, B.R.; Miller, D.C. Contemporary Use of Initial Active Surveillance Among Men in Michigan with Low-risk Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Dailey, R.K.; Eggly, S.; Neale, A.V.; Schwartz, K.L. Men’s Perspectives on Selecting Their Prostate Cancer Treatment. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2011, 103, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinping, X.; James, J.; Julie, J.R.; Joel, A.; Joe, L.; Margaret, H.-R.; Kendra, L.S. Patients’ Survival Expectations With and Without Their Chosen Treatment for Prostate Cancer. Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Janisse, J.; Ruterbusch, J.; Ager, J.; Schwartz, K.L. Racial Differences in Treatment Decision-Making for Men with Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: A Population-Based Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2016, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Neale, A.V.; Dailey, R.K.; Eggly, S.; Schwartz, K.L. Patient Perspective on Watchful Waiting/Active Surveillance for Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2012, 25, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanez, B.; Bustillo, N.E.; Antoni, M.H.; Lechner, S.C.; Dahn, J.; Kava, B.; Penedo, F.J. The importance of perceived stress management skills for patients with prostate cancer in active surveillance. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeliadt, S.B.; Moinpour, C.M.; Blough, D.K.; Penson, D.F.; Hall, I.J.; Smith, J.L.; Ekwueme, D.U.; Thompson, I.M.; E Keane, T.; Ramsey, S.D. Preliminary treatment considerations among men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Am. J. Manag. Care 2010, 16, e121–e130. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Meeks, W.; Fang, R.; Gaylis, F.D.; Catalona, W.J.; Makarov, D.V. Time Trends and Variation in the Use of Active Surveillance for Management of Low-risk Prostate Cancer in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e231439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C.; Subramanian, L.; Skolarus, T.A.; Hawley, S.T.; Rankin, A.; Fetters, M.D.; Witzke, K.; Borza, T.; Radhakrishnan, A. Multi-level Factors to Build Confidence and Support in Active Surveillance for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer: A Qualitative Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2025, 40, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penson, D.F. Factors Influencing Patients’ Acceptance and Adherence to Active Surveillance. JNCI Monogr. 2012, 2012, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donachie, K.; Cornel, E.; Pelgrim, T.; Michielsen, L.; Langenveld, B.; Adriaansen, M.; Bakker, E.; Lechner, L. What interventions affect the psychosocial burden experienced by prostate cancer patients undergoing active surveillance? A scoping review. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4699–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.; Koppie, T.M.; Wu, D.; Meng, M.V.; Grossfeld, G.D.; Sadesky, N.; Lubeck, D.P.; Carroll, P.R. Sociodemographic characteristics and health related quality of life in men attending prostate cancer support groups. J. Urol. 2002, 168, 2092–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.M.; King, L.E.; Withington, J.; Amin, M.B.; Andrews, M.; Briers, E.; Chen, R.C.; Chinegwundoh, F.I.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Crowe, J.; et al. Best Current Practice and Research Priorities in Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer—A Report of a Movember International Consensus Meeting. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 6, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year | Country | Study Design | Study Population | Age (Mean) | MMAT (Quality Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aizer et al., 2013 [32] | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Patients with low-risk PCa | MC: 63 IP: 61 | ***** |

| Al Hussein Al Awamlh, 2023 [33] | USA | Qualitative interview study | PCa survivors who underwent AS, RP, or RT | n/a | ***** |

| Al Hussein Al Awamlh et al., 2020 [34] | USA | Retrospective cohort registry study | Men with localized PCa | Conservative treatment: 65.12 Definitive treatment: 63.13 | ***** |

| Alvisi et al., 2020 [35] | Italy | Prospective cohort survey study | AS patients | n/a | **** |

| Anandadas et al., 2011 [36] | UK | Prospective survey study | Patients with low-risk PCa | AS: 64.8 BR: 62.0 CRT: 64.3 S: 62.5 | **** |

| Anderson et al., 2014 [37] | Australia | Prospective cohort survey study | AS patients | 65.7 | ** |

| Anderson et al., 2022 [38] | USA | Cross-sectional analysis | Men with localized PCa | n/a | **** |

| Ansmann et al., 2018 [39] | Germany | Prospective observational survey study | AS and RP patients | AS: 67.7 RP: 63.9 | **** |

| Baba et al., 2021 [40] | Germany | Observational, cross-sectional survey study | AS, RP, biochemical relapse, and metastasized disease patients | 68.2 | **** |

| Banerji et al., 2017 [41] | USA | Prospective survey study | AS and RT patients | AS: 64 EBRT: 65 | ***** |

| Barocas et al., 2017 [42] | USA | Prospective, population-based cohort survey study | RT, S, and AS patients | 63.8 | **** |

| Basak et al., 2022 [43] | USA | Population-based prospective cohort survey study | Patients with low-risk PCa | n/a | ** |

| Beckmann et al., 2021 [44] | UK | Qualitative interview study | Men who discontinued AS for AT | 64 | ***** |

| Beckmann et al., 2022 [45] | UK | Patient and public involvement Delphi study | AS patients and healthcare providers | n/a | *** |

| Beckmann et al., 2019 [46] | Sweden | Retrospective register-based study | Men with low-risk PCa | 63.9 | **** |

| Bellardita et al., 2013 [47] | Italy | Prospective cohort study | AS patients | 67 | **** |

| Bellardita et al., 2019 [48] | Italy | Prospective survey study | AS patients | 64.8 | ***** |