Normalising the Implementation of Pharmacogenomic (PGx) Testing in Adult Mental Health Settings: A Theory-Based Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify barriers hindering the uptake of PGx;

- Determine facilitators helping the adoption of PGx prescribing practices;

- Map key barriers and facilitators to NPT constructs to help inform future implementation of PGxT in MH settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Search Strategy

2.2.1. Phase One—Developing the Search Strategy

2.2.2. Phase Two—Database Searching

2.2.3. Phase Three—Reference Searching and Grey Literature

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis/Synthesis

- Mind mapping raw barriers/facilitators to enable data familiarization;

- Tabulation of raw barriers/facilitators to sub-constructs of the NPT coding framework;

- Summarising of barriers/facilitators within sub-constructs of NPT;

- Theme construction of barriers/facilitators within NPT sub-constructs;

- Broad theme construction across NPT constructs.

2.6. Quality Appraisal

2.7. Patient Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE)

3. Results

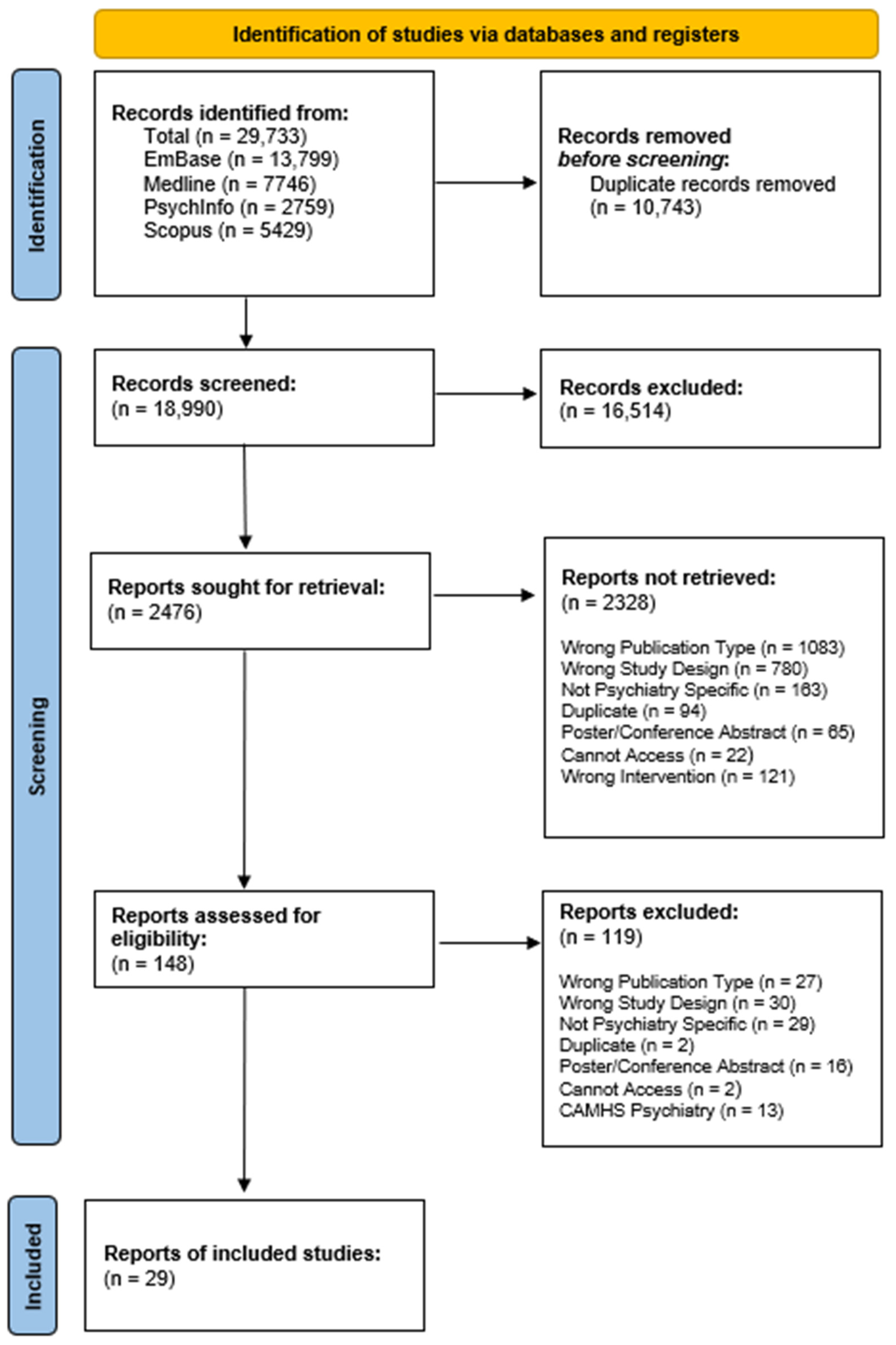

3.1. Search Results and Included Studies

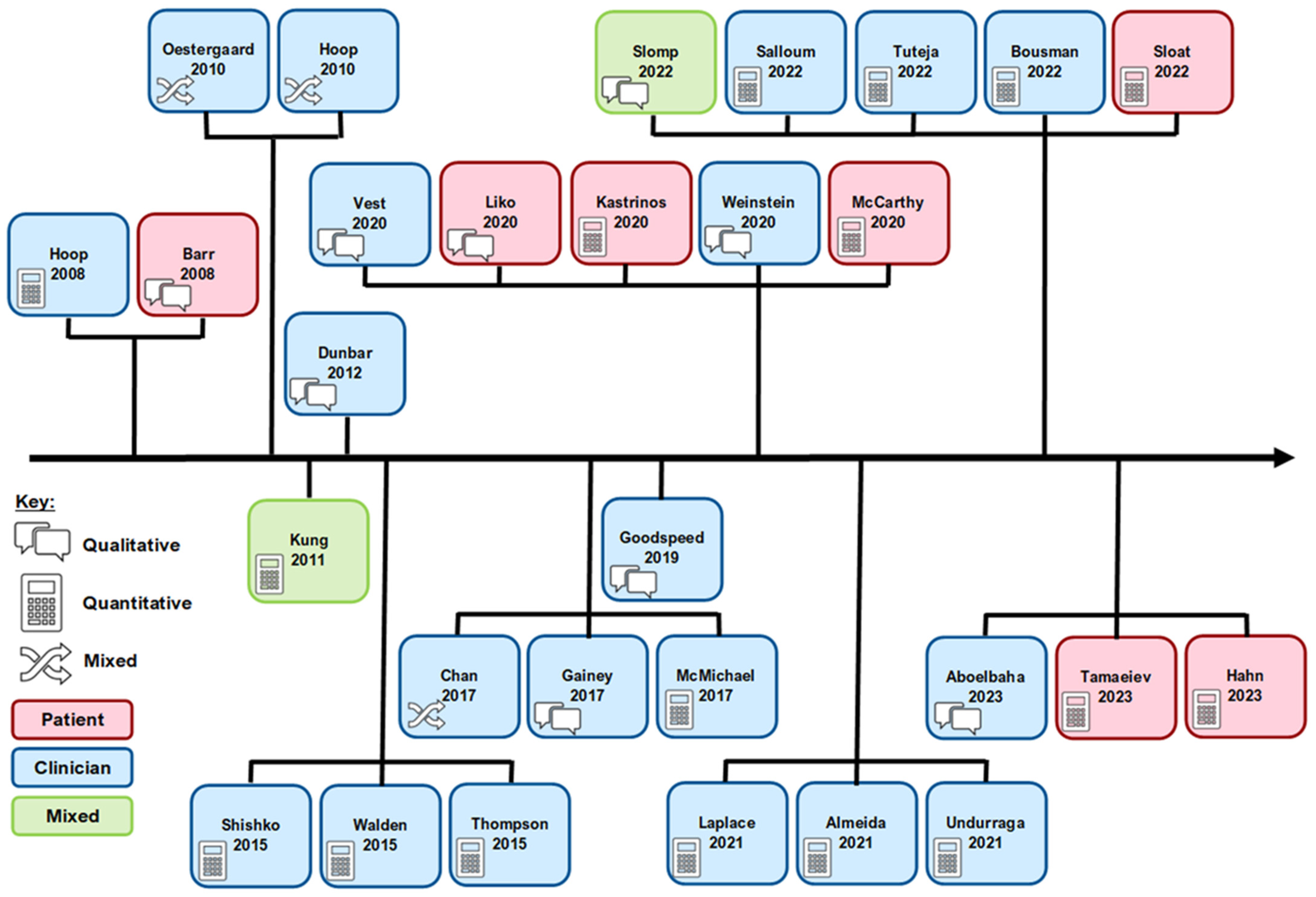

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Quality Appraisal

3.4. Barriers and Facilitators

3.5. Coherence

3.5.1. Barriers

3.5.2. Facilitators

3.6. Cognitive Participation

3.6.1. Barriers

3.6.2. Facilitators

3.7. Collective Action

3.7.1. Barriers

3.7.2. Facilitators

3.8. Reflexive Monitoring

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Future Policy and Research

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder |

| BAP | British Association of Psychopharmacology |

| CAMH | Child and Adolescent Mental Health |

| CPIC | Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium |

| DYPD | Dihydropyrmidine Dehydrogenase |

| EHR | Electronic Health Records |

| E&T | Education and Training |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (USA) |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MH | Mental Health |

| NHS | National Health Service (UK) |

| NPT | Normalisation Process Theory |

| PGx | Pharmacogenomics |

| PGxT | Pharmacogenomic Testing |

| QATSDD | Quality Assessment Tool |

| QuADS | Quality Assessment for Diverse Studies |

| RCPsych | Royal College of Psychiatrists |

| UK | United Kingdom |

Appendix A

| Section and Topic | # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | See Below |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 2–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 5 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 3 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Appendix B |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 5 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 5–6 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 5 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 5 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 6 and SM2 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | NA |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | 6 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | 6 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | 6 and SM1 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 6 and SM1 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | NA | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | NA |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | 6, 14, 26 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 7,8 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | NA | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 9–13 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | SM2 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | 15–22 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | SM2 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | NA | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | NA | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | NA |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | NA |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 23–24 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 26 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 26 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 24–25 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | 3 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | 3 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | NA | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | 28 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 28 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | SM2 |

| Description: this checklist highlights where relevant information for the PRISMA guidelines can be found in the manuscript. | |||

| Section and Topic | # | Checklist Item | Reported (Yes/No) |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Y |

| BACKGROUND | |||

| Objectives | 2 | Provide an explicit statement of the main objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Y |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 3 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. | N |

| Information sources | 4 | Specify the information sources (e.g., databases, registers) used to identify studies and the date when each was last searched. | Y |

| Risk of bias | 5 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies. | Y |

| Synthesis of results | 6 | Specify the methods used to present and synthesise results. | Y |

| RESULTS | |||

| Included studies | 7 | Give the total number of included studies and participants and summarise relevant characteristics of studies. | Y |

| Synthesis of results | 8 | Present results for main outcomes, preferably indicating the number of included studies and participants for each. If meta-analysis was done, report the summary estimate and confidence/credible interval. If comparing groups, indicate the direction of the effect (i.e., which group is favoured). | Y |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Limitations of evidence | 9 | Provide a brief summary of the limitations of the evidence included in the review (e.g., study risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision). | N |

| Interpretation | 10 | Provide a general interpretation of the results and important implications. | Y |

| OTHER | |||

| Funding | 11 | Specify the primary source of funding for the review. | N |

| Registration | 12 | Provide the register name and registration number. | Y |

| Description: this checklist highlights the included information in the abstract. Where answered ‘N’ information is provided in the full manuscript. ‘N’ = No; ‘Y’ = Yes. | |||

Appendix B

| EmBase | ||

| No. | Search | Hits |

| #80 | #19 AND #47 AND #78 | 12,819 |

| #79 | #21 AND #47 AND #78 | |

| #78 | #48 OR #49 OR #50 OR #51 OR #52 OR #53 OR #54 OR #55 OR #56 OR #57 OR #58 OR #59 OR #60 OR #61 OR #62 OR #63 OR #64 OR #65 OR #66 OR #67 OR #68 OR #69 OR #70 OR #71 OR #72 OR #73 OR #74 OR #75 OR #76 OR #77 | |

| #77 | ‘questionnaire’/exp | |

| #76 | ‘interview’/exp | |

| #75 | ‘experience’/exp | |

| #74 | ‘perception’/exp | |

| #73 | ‘health personnel attitude’/exp | |

| #72 | ‘attitude’/exp | |

| #71 | ‘use of’ | |

| #70 | ‘survey*’ | |

| #69 | ‘questionnaire*’ | |

| #68 | ‘interview*’ | |

| #67 | ‘focus group*’ | |

| #66 | ‘facilitator*’ | |

| #65 | ‘enabler*’ | |

| #64 | ‘challenge*’ | |

| #63 | ‘barrier*’ | |

| #62 | ‘believe’ | |

| #61 | ‘belief*’ | |

| #60 | ‘experience*’ | |

| #59 | ‘value’ | |

| #58 | ‘perception*’ | |

| #57 | perceive | |

| #56 | adoption | |

| #55 | implementation | |

| #54 | ‘comprehension’ | |

| #53 | understand*’ | |

| #52 | ‘opinion*’ | |

| #51 | ‘health personnel attitude’ | |

| #50 | ‘attitude*’ | |

| #49 | ‘perspective*’ | |

| #48 | ‘view*’ | |

| #47 | #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42 OR #43 OR #44 OR #45 OR #46 | |

| #46 | ‘psychosis’/exp | |

| #45 | ‘schizophrenia’/exp | |

| #44 | ‘bipolar disorder’/exp | |

| #43 | ‘anxiety disorder’/exp | |

| #42 | ‘major depression’/exp | |

| #41 | ‘mood stabilizer’ | |

| #40 | ‘mood stabiliser’ | |

| #39 | ‘antipsychotic*’ | |

| #38 | ‘antidepressant*’ | |

| #37 | ‘psychotic’ | |

| #36 | ‘psychosis’ | |

| #35 | ‘schizophren*’ | |

| #34 | ‘bipolar*’ | |

| #33 | ‘affective*’ | |

| #32 | ‘anxiety’ | |

| #31 | ‘depress*’ | |

| #30 | ‘mood disorder’/exp | |

| #29 | ‘mood disorder’ | |

| #28 | ‘psychiatry’/exp | |

| #27 | ‘psychiatr*’ | |

| #26 | ‘mental disease’/exp | |

| #25 | ‘mental health*’ | |

| #24 | ‘mental disorder’ | |

| #23 | ‘mental disease’ | |

| #22 | ‘mental illness’ | |

| #21 | #19 OR #20 | |

| #20 | #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 | |

| #19 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 | |

| #18 | ‘genetic screening’/exp | |

| #17 | ‘genetic information’ | |

| #16 | ‘genetic variation’ | |

| #15 | ‘genetic profile’ | |

| #14 | ‘genetic variant*’ | |

| #13 | ‘genetic test*’ | |

| #12 | personalized medicine’/exp | |

| #11 | ‘precision prescribing’ | |

| #10 | ‘precision medicine’ | |

| #9 | ‘personali*ed prescribing’ | |

| #8 | ‘personalized medicine’ | |

| #7 | ‘personalised medicine’ | |

| #6 | ‘pharmacogenetic testing’/exp | |

| #5 | ‘pharmacogen* test*’ | |

| #4 | ‘pharmacogenetics’/exp | |

| #3 | ‘pharmacogenetic*’ | |

| #2 | ‘pharmacogenomics’/exp | |

| #1 | ‘pharmacogenomic*’ | |

| Medline | ||

| #79 | S12 AND S49 AND S77 | 7400 |

| #78 | S21 AND S49 AND S77 | 16,920 |

| #77 | S50 OR S51 OR S52 OR S53 OR S54 OR S55 OR S56 OR S57 OR S58 OR S59 OR S60 OR S61 OR S62 OR S63 OR S64 OR S65 OR S66 OR S67 OR S68 OR S69 OR S70 OR S71 OR S72 OR S73 OR S74 OR S75 OR S76 | |

| #76 | “use of” | |

| #75 | “survey” | |

| #74 | (MH “Surveys and Questionnaires”) | |

| #73 | “questionnaire” | |

| #72 | (MH “Focus Groups”) | |

| #71 | “focus group*” | |

| #70 | “interview*” | |

| #69 | “facilitator*” | |

| #68 | “enabler*” | |

| #67 | “challenge*” | |

| #66 | “barrier*” | |

| #65 | “believe” | |

| #64 | “belief*” | |

| #63 | “experience*” | |

| #62 | “value” | |

| #61 | “perception*” | |

| #60 | (MH “Perception”) | |

| #59 | “perceive” | |

| #58 | “adoption” | |

| #57 | (MH “Implementation Science”) | |

| #56 | “implementation” | |

| #55 | “understand*” | |

| #54 | “opinion*” | |

| #53 | (MH “Attitude of Health Personnel”) OR (MH “Attitude”) | |

| #52 | “attitude*” | |

| #51 | “perspective*” | |

| #50 | “view*” | |

| #49 | S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 OR S48 | |

| #48 | “mood stabiliser*” | |

| #47 | (MH “Antipsychotic Agents”) | |

| #46 | “antipsychotic*” | |

| #45 | (MH “Serotonin and Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors”) OR (MH “Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors”) | |

| #44 | (MH “Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic”) OR (MH “Antidepressive Agents”) | |

| #43 | “antidepressant*” | |

| #42 | (MH “Psychotic Disorders”) | |

| #41 | (MH “Schizophrenia”) OR (MH “Schizophrenia, Catatonic”) OR (MH “Schizophrenia, Paranoid”) OR (MH “Schizophrenia, Treatment-Resistant”) OR (MH “Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders”) | |

| #40 | (MH “Bipolar Disorder”) OR (MH “Bipolar and Related Disorders”) | |

| #39 | (MH “Anxiety”) OR (MH “Anxiety Disorders”) | |

| #38 | (MH “Depression”) OR (MH “Depressive Disorder, Treatment-Resistant”) OR (MH “Depressive Disorder”) OR (MH “Depressive Disorder, Major”) OR (MH “Depression, Chemical”) | |

| #37 | “psychotic*” | |

| #36 | “psychosis” | |

| #35 | “schizophren*” | |

| #34 | “bipolar” | |

| #33 | “anxiety” | |

| #32 | “depress*” | |

| #31 | (MH “Mood Disorders”) OR (MH “Bipolar Disorder”) OR (MH “Affective Disorders, Psychotic”) | |

| #30 | “mood disorder” | |

| #29 | (MH “Psychiatry”) | |

| #28 | “psychiatr*” | |

| #27 | (MH “Mental Health”) OR (MH “Mental Health Services”) | |

| #26 | (MH “Mental Disorders”) | |

| #25 | “mental health*” | |

| #24 | “mental disease” | |

| #23 | “mental disorder” | |

| #22 | “mental illness” | |

| #21 | S12 OR S20 | |

| #20 | S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 | |

| #19 | (MH “Pharmacogenomic Variants”) OR (MH “Genetic Variation”) OR (MH “Polymorphism, Genetic”) | |

| #18 | (MH “Genetic Testing”) | |

| #17 | “genetic information” | |

| #16 | “genetic screening” | |

| #15 | “genetic variation” | |

| #14 | “genetic variant*” | |

| #13 | “genetic test*” | |

| #12 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 | |

| #11 | (MH “Precision Medicine”) | |

| #10 | “precision prescribing” | |

| #9 | “personalized prescribing” | |

| #8 | “personalised prescribing” | |

| #7 | “precision medicine” | |

| #6 | “personalised medicine” | |

| #5 | “personalized medicine” | |

| #4 | (MH “Pharmacogenetics”) OR (MH “Pharmacogenomic Testing”) OR (MH “Pharmacogenomic Variants”) | |

| #3 | “pharmacogenetic test*” | |

| #2 | “pharmacogenetic*” | |

| #1 | “pharmacogenomic*” | |

| PsycInfo | ||

| No. | Term | Hits |

| S73 | S15 AND S48 AND S71 | 2680 |

| S72 | S22 AND S48 AND S71 | |

| S71 | S49 OR S50 OR S51 OR S52 OR S53 OR S54 OR S55 OR S56 OR S57 OR S58 OR S59 OR S60 OR S61 OR S62 OR S63 OR S64 OR S65 OR S66 OR S67 OR S68 OR S69 OR S70 | |

| S70 | (((((DE “Attitudes”) OR (DE “Perception”)) AND (DE “Semi-Structured Interview” OR DE “Focus Group Interview” OR DE “Interviews”)) OR (DE “Focus Group”)) OR (DE “Surveys”)) OR (DE “Questionnaires”) | |

| S69 | “use of” | |

| S68 | survey* | |

| S67 | questionnaire | |

| S66 | “focus group*” | |

| S65 | interview* | |

| S64 | facilitator* | |

| S63 | enabler* | |

| S62 | challenge* | |

| S61 | barrier* | |

| S60 | believe | |

| S59 | belief* | |

| S58 | experience* | |

| S57 | value | |

| S56 | perceive | |

| S55 | adoption | |

| S54 | implementation | |

| S53 | understand* | |

| S52 | opinion* | |

| S51 | attitude* | |

| S50 | perspective* | |

| S49 | view* | |

| S48 | S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 | |

| S47 | “mood stabili*er” | |

| S46 | DE “Affective Disorders” | |

| S45 | DE “Tricyclic Antidepressant Drugs” OR DE “Antidepressant Drugs” OR DE “Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors” | |

| S44 | DE “Neuroleptic Drugs” OR DE “Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome” OR DE “Psychotropic Drugs” | |

| S43 | antidepressant* | |

| S42 | antipsychotic* | |

| S41 | DE “Psychosis” | |

| S40 | DE “Schizophrenia” OR DE “Schizophrenia (Disorganized Type)” OR DE “Childhood Onset Schizophrenia” OR DE “Undifferentiated Schizophrenia” OR DE “Process Schizophrenia” OR DE “Paranoid Schizophrenia” OR DE “Catatonic Schizophrenia” OR DE “Acute Schizophrenia” OR DE “Schizophreniform Disorder” OR DE “Schizoaffective Disorder” | |

| S39 | DE “Bipolar Disorder” OR DE “Bipolar I Disorder” OR DE “Bipolar II Disorder” OR DE “Mood Stabilizers” | |

| S38 | DE “Anxiety” OR DE “Anxiety Disorders” OR DE “Generalized Anxiety Disorder” | |

| S37 | DE “Major Depression” OR DE “Depression (Emotion)” OR DE “Postpartum Depression” OR DE “Reactive Depression” OR DE “Treatment Resistant Depression” OR DE “Bipolar Disorder” OR DE “Late Life Depression” OR DE “Recurrent Depression” OR DE “Endogenous Depression” OR DE “Atypical Depression” OR DE “Long-term Depression (Neuronal)” OR DE “Seasonal Affective Disorder” | |

| S36 | psychotic | |

| S35 | psychosis | |

| S34 | schizophren* | |

| S33 | bipolar | |

| S32 | anxiety | |

| S31 | depressi* | |

| S30 | DE “Mental Health” OR DE “Mental Health Services” | |

| S29 | DE “Psychiatry” | |

| S28 | “mood disorder” | |

| S27 | psychiatr* | |

| S26 | “mental health*” | |

| S25 | “mental disease” | |

| S24 | “mental disorder” | |

| S23 | “mental illness” | |

| S22 | S15 OR S21 | |

| S21 | S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 | |

| S20 | DE “Genetic Testing” | |

| S19 | “genetic information” | |

| S18 | “genetic screen*” | |

| S17 | “genetic varia*” | |

| S16 | “genetic test*” | |

| S15 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 | |

| S14 | DE “Precision Medicine” | |

| S13 | “personalized prescribing” | |

| S12 | “personalized medicine” | |

| S11 | “precision prescribing” | |

| S10 | “precision medicine” | |

| S9 | “personalised prescribing” | |

| S8 | “personalised medicine” | |

| S7 | DE “Pharmacogenetics” | |

| S6 | “pharmacogenomic testing” | |

| S5 | “pharmacogenetic testing” | |

| S4 | pharmacogenetic* | |

| S3 | pharmacogenetics | |

| S2 | pharmacogenomic* | |

| S1 | Pharmacogenomics | |

| Scopus | ||

| No. | Term | Hits |

| S73 | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“view*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“perspective*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“attitude*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“opinion*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“understand*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“implementation”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“adoption”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“perceive”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“value”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“experience*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“belief*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“believe”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“barrier*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“challenge*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“enabler*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“facilitator*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“interview*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“focus group*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“questionnaire”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“survey*”))) AND (((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“precision prescribing”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“precision medicine”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“personalized prescribing”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“personalised prescribing”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“personalized medicine”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“personalised medicine”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“pharmacogenomic testing”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“pharmacogenetic testing”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (pharmacogenetic*)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (pharmacogenetics)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (pharmacogenomic*)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (pharmacogenomics))) AND ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mental illness”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mental disorder”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mental disease”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mental health”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“psychiatr*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mood disorder”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“depressi*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“anxiety”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“bipolar”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“schizophren*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“psychosis”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“psychotic”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“affective”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“antipsychotic*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“antidepressant*”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mood stabili*er*”)))) | 5246 |

| Description: in the table is the full searching strategy used during in the review. | ||

References

- Steel, Z.; Marnane, C.; Iranpour, C.; Chey, T.; Jackson, J.W.; Patel, V.; Silove, D. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabeea, S.A.; Merchant, H.A.; Khan, M.U.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. Surging trends in prescriptions and costs of antidepressants in England amid COVID-19. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 29, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhagiar, K.; Ghafouri, M.; Dey, M. Oral antipsychotic prescribing and association with neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status: Analysis of time trend of routine primary care data in England, 2011–2016. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Burschinski, A.; Peter, N.; Wang, D.; Dong, S.; Huhn, M.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Salanti, G.; Davis, J.M. Long-term efficacy of antipsychotic drugs in initially acutely ill adults with schizophrenia: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhn, M.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Krause, M.; Samara, M.; Peter, N.; Arndt, T.; Bäckers, L.; Rothe, P.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semahegn, A.; Torpey, K.; Manu, A.; Assefa, N.; Tesfaye, G.; Ankomah, A. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braund, T.A.; Tillman, G.; Palmer, D.M.; Gordon, E.; Rush, A.J.; Harris, A.W.F. Antidepressant side effects and their impact on treatment outcome in people with major depressive disorder: An iSPOT-D report. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 53, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucifora, F.C.; Woznica, E.; Lee, B.J.; Cascella, N.; Sawa, A. Treatment resistant schizophrenia: Clinical, biological, and therapeutic perspectives. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 131, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, S.S.; Stewart, V.; Wheeler, A.J.; Kelly, F.; Stapleton, H. Medication management in the context of mental illness: An exploratory study of young people living in Australia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.M.; McLeod, H.L.; Relling, M.V.; Williams, M.S.; Mensah, G.A.; Peterson, J.F.; Van Driest, S.L. Pharmacogenomics. Lancet 2019, 394, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dere, W.H.; Suto, T.S. The role of pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics in improving translational medicine. Clin. Cases Min. Bone Metab. 2009, 6, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, G.; Lavertu, A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Klein, T.E.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Altman, R.B. Pharmacogenetics at Scale: An Analysis of the UK Biobank. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousman, C.A.; Bengesser, S.A.; Aitchison, K.J.; Amare, A.T.; Aschauer, H.; Baune, B.T.; Asl, B.B.; Bishop, J.R.; Burmeister, M.; Chaumette, B.; et al. Review and Consensus on Pharmacogenomic Testing in Psychiatry. Pharmacopsychiatry 2021, 54, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/science-and-research-drugs/table-pharmacogenomic-biomarkers-drug-labeling (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- CPIC. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Gene-Drug Pairs. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/genes-drugs/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- PharmGKB. Available online: https://www.pharmgkb.org/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Personalised Prescribing: Using Pharmacogenomics to Improve Patient Outcomes; Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society: London, UK, 2022.

- Pain, O.; Hodgson, K.; Trubetskoy, V.; Ripke, S.; Marshe, V.S.; Adams, M.J.; Byrne, E.M.; Campos, A.I.; Carrillo-Roa, T.; Cattaneo, A.; et al. Identifying the Common Genetic Basis of Antidepressant Response. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2022, 2, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.T. The Pharmacogenetic Impact on the Pharmacokinetics of ADHD Medications. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2547, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, M.J.; Salazar, J.; Hernández, M.H. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotics: Clinical utility and implementation. Behav. Brain Res. 2021, 401, 113058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousman, C.; Maruf, A.A.; Müller, D.J. Towards the integration of pharmacogenetics in psychiatry: A minimum, evidence-based genetic testing panel. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swen, J.J.; van der Wouden, C.H.; Manson, L.E.N.; Abdullah-Koolmees, H.; Blagec, K.; Blagus, T.; Böhringer, S.; Cambon-Thomsen, A.; Cecchin, E.; Cheung, K.-C.; et al. A 12-gene pharmacogenetic panel to prevent adverse drug reactions: An open-label, multicentre, controlled, cluster-randomised crossover implementation study. Lancet 2023, 401, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, M.C.; Maciel, A.; Gariepy, J.F.; Cullors, A.; Saldivar, J.S.; Taylor, D.; Centeno, J.; Garces, J.A.; Vaishnavi, S. Clinical Impact of Pharmacogenetic-Guided Treatment for Patients Exhibiting Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017, 19, 16m02036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.C.; Stanton, J.D.; Bharthi, K.; Maruf, A.A.; Müller, D.J.; Bousman, C.A. Pharmacogenomic Testing and Depressive Symptom Remission: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective, Controlled Clinical Trials. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; An, Z. Effect of pharmacogenomics testing guiding on clinical outcomes in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunka, M.; Wong, G.; Kim, D.; Edwards, L.; Austin, J.; Doyle-Waters, M.M.; Gaedigk, A.; Bryan, S. Evaluating treatment outcomes in pharmacogenomic-guided care for major depression: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 321, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, D.; Omar, O.; Arora, T.; Östlundh, L.; Ramaraj, R.; Javaid, S.; Govender, R.D.; Ali, B.R.; Patrinos, G.P.; Young, A.H.; et al. Effectiveness of pharmacogenomic tests including CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genomic variants for guiding the treatment of depressive disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 144, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadullah Khani, N.; Hudson, G.; Mills, G.; Ramesh, S.; Varney, L.; Cotic, M.; Abidoph, R.; Richards-Belle, A.; Carrascal-Laso, L.; Franco-Martin, M.; et al. A systematic review of pharmacogenetic testing to guide antipsychotic treatment. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, M.M.; Smith, R.L.; Haslemo, T.; Molden, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Effect of CYP2D6 genotype on exposure and efficacy of risperidone and aripiprazole: A retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, F.; Bukvic, N.; Pavlovic, Z.; Miljevic, C.; Pesic, V.; Molden, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Leucht, S.; Jukic, M.M. Association of CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 Poor and Intermediate Metabolizer Status With Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Exposure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Chacartegui, P.; Villapalos-García, G.; Zubiaur, P.; Abad-Santos, F.; Koller, D. Genetic Polymorphisms Associated With the Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Adverse Effects of Olanzapine, Aripiprazole and Risperidone. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 711940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelgrim, T.A.D.; Philipsen, A.; Young, A.H.; Juruena, M.; Jimenez, E.; Vieta, E.; Jukić, M.; Van Der Eycken, E.; Heilbronner, U.; Moldovan, R.; et al. A New Intervention for Implementation of Pharmacogenetics in Psychiatry: A Description of the PSY-PGx Clinical Study. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbarian, S.; Wong, G.W.K.; Bunka, M.; Edwards, L.; Cressman, S.; Conte, T.; Price, M.; Schuetz, C.; Riches, L.; Landry, G.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacogenomic-guided treatment for major depression. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2023, 195, E1499–E1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamperis, K.; Koromina, M.; Papantoniou, P.; Skokou, M.; Kanellakis, F.; Mitropoulos, K.; Vozikis, A.; Müller, D.J.; Patrinos, G.P.; Mitropoulou, C. Economic evaluation in psychiatric pharmacogenomics: A systematic review. Pharmacogenom. J. 2021, 21, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, R.H.; Mehta, R.; Edwards, A.M.; Tiwari, A.; Imbens, G.W. Pharmacogenetic testing among patients with mood and anxiety disorders is associated with decreased utilization and cost: A propensity-score matched study. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerness, J.; Fonseca, E.; Hess, G.P.; Scott, R.; Gardner, K.R.; Koffler, M.; Fava, M.; Perlis, R.H.; Brennan, F.X.; Lombard, J. Pharmacogenetic-guided psychiatric intervention associated with increased adherence and cost savings. Am. J. Manag. Care 2014, 20, e146–e156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Winner, J.G.; Carhart, J.M.; Altar, C.A.; Goldfarb, S.; Allen, J.D.; Lavezzari, G.; Parsons, K.K.; Marshak, A.G.; Garavaglia, S.; Dechairo, B.M. Combinatorial pharmacogenomic guidance for psychiatric medications reduces overall pharmacy costs in a 1 year prospective evaluation. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2015, 31, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matey, E.T.; Ragan, A.K.; Oyen, L.J.; Vitek, C.R.; Aoudia, S.L.; Ragab, A.K.; Fee-Schroeder, K.C.; Black, J.L.; Moyer, A.M.; Nicholson, W.T.; et al. Nine-gene pharmacogenomics profile service: The Mayo Clinic experience. Pharmacogenom. J. 2022, 22, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, S.B.; Kantor, A. Horizon Scan of Clinical Laboratories Offering Pharmacogenetic Testing. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, A.A.; Fan, M.; Arnold, P.D.; Müller, D.J.; Aitchison, K.J.; Bousman, C.A. Pharmacogenetic Testing Options Relevant to Psychiatry in Canada: Options de tests pharmacogénétiques pertinents en psychiatrie au Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2020, 65, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornley, T.; Esquivel, B.; Wright, D.J.; Dop, H.V.D.; Kirkdale, C.L.; Youssef, E. Implementation of a Pharmacogenomic Testing Service through Community Pharmacy in the Netherlands: Results from an Early Service Evaluation. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Everything You Need to Know about the NHS Genomic Medicine Service. Available online: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/feature/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-nhs-genomic-medicine-service (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- McDermott, J.H.; Mahaveer, A.; James, R.A.; Booth, N.; Turner, M.; Harvey, K.E.; Miele, G.; Beaman, G.M.; Stoddard, D.C.; Tricker, K.; et al. Rapid Point-of-Care Genotyping to Avoid Aminoglycoside-Induced Ototoxicity in Neonatal Intensive Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, D.K.; Fong, C.; Arouri, F.; Cortez, L.; Katifi, H.; Gonzalez-Exposito, R.; Razzaq, M.B.; Li, S.; Macklin-Doherty, A.; Hernandez, M.A.; et al. Impact of pharmacogenomic DPYD variant guided dosing on toxicity in patients receiving fluoropyrimidines for gastrointestinal cancers in a high-volume tertiary centre. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.S.; Kirchner, J. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020, 283, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, E.; Treweek, S.; Pope, C.; MacFarlane, A.; Ballini, L.; Dowrick, C.; Finch, T.; Kennedy, A.; Mair, F.; O’Donnell, C.; et al. Normalisation process theory: A framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangash, H.; Kullo, I.J. Implementation Science to Increase Adoption of Genomic Medicine: An Urgent Need. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, C.R.; Cummings, A.; Girling, M.; Bracher, M.; Mair, F.S.; May, C.M.; Murray, E.; Myall, M.; Rapley, T.; Finch, T. Using Normalization Process Theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.R.; Albers, B.; Bracher, M.; Finch, T.L.; Gilbert, A.; Girling, M.; Greenwood, K.; MacFarlane, A.; Mair, F.S.; May, C.M.; et al. Translational framework for implementation evaluation and research: A normalisation process theory coding manual for qualitative research and instrument development. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, A.; Fylan, B.; Bristow, G.C.; Sagoo, G.S.; Dalton, C.; Cardno, A.; Sohal, J.; McLean, S.L. What Are the Barriers and Enablers to the Implementation of Pharmacogenetic Testing in Mental Health Care Settings? Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 740216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, F.S.; May, C.; O’Donnell, C.; Finch, T.; Sullivan, F.; Murray, E. Factors that promote or inhibit the implementation of e-health systems: An explanatory systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeowo, D.A.; Zaidi, S.T.R.; Fylan, B.; Alldred, D.P. Barriers and facilitators of implementing proactive deprescribing within primary care: A systematic review. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 31, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Jones, B.; Gardner, P.; Lawton, R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): An appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote X9; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aboelbaha, S.; Zolezzi, M.; Abdallah, O.; Eltorki, Y. Mental Health Prescribers’ Perceptions on the Use of Pharmacogenetic Testing in the Management of Depression in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Pharmgenom. Pers. Med. 2023, 16, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B.C.; Goncalves, E.D.; de Sousa, M.H.; Osis, M.; de Brito Mota, M.J.B.; Planello, A.C. Perception and knowledge of pharmacogenetics among Brazilian psychiatrists. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.; Rose, D. The great ambivalence: Factors likely to affect service user and public acceptability of the pharmacogenomics of antidepressant medication. Sociol. Health Illn. 2008, 30, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousman, C.A.; Oomen, A.; Jessel, C.D.; Tampi, R.R.; Forester, B.P.; Eyre, H.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Muller, D.J. Perspectives on the Clinical Use of Pharmacogenetic Testing in Late-Life Mental Healthcare: A Survey of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry Membership. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 30, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.Y.W.; Chua, B.Y.; Subramaniam, M.; Suen, E.L.K.; Lee, J. Clinicians’ perceptions of pharmacogenomics use in psychiatry. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, L.; Butler, R.; Wheeler, A.; Pulford, J.; Miles, W.; Sheridan, J. Clinician experiences of employing the AmpliChip ® CYP450 test in routine psychiatric practice. J. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 26, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainey, T. Pharmacogenetic Testing in Outpatient Mental Health Clinics; University of Missouri-Columbia: Columbia, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodspeed, A.; Kostman, N.; Kriete, T.E.; Longtine, J.W.; Smith, S.M.; Marshall, P.; Williams, W.; Clark, C.; Blakeslee, W.W. Leveraging the utility of pharmacogenomics in psychiatry through clinical decision support: A focus group study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2019, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.; Frantz, A.; Eckert, A.; Reif, A. Barriers for Implementation of PGx Testing in Psychiatric Hospitals in Germany: Results of the FACT-PGx Study. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr. 2023, 92, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoop, J.G.; Roberts, L.W.; Green Hammond, K.A.; Cox, N.J. Psychiatrists’ Attitudes Regarding Genetic Testing and Patient Safeguards: A Preliminary Study. Genet. Test. 2008, 12, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoop, J.G.; Lapid, M.I.; Paulson, R.M.; Roberts, L.W. Clinical and ethical considerations in pharmacogenetic testing: Views of physicians in 3 “early adopting” departments of psychiatry. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastrinos, A.; Campbell-Salome, G.; Shelton, S.; Peterson, E.B.; Bylund, C.L. PGx in psychiatry: Patients’ knowledge, interest, and uncertainty management preferences in the context of pharmacogenomic testing. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, S.; Allen, J.D. Patients and Clinicians Report Higher-Than-Average Satisfaction With Psychiatric Genotyping for Depressed Inpatients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 262–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Laplace, B.; Calvet, B.; Lacroix, A.; Mouchabac, S.; Picard, N.; Girard, M.; Charles, E. Acceptability of Pharmacogenetic Testing among French Psychiatrists, a National Survey. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liko, I.; Lai, E.; Griffin, R.J.; Aquilante, C.L.; Lee, Y.M. Patients’ Perspectives on Psychiatric Pharmacogenetic Testing. Pharmacopsychiatry 2020, 53, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.J.; Chen, Y.; Demodena, A.; Fisher, E.; Golshan, S.; Suppes, T.; Kelsoe, J.R. Attitudes on pharmacogenetic testing in psychiatric patients with treatment-resistant depression. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A.J.; Boeri, M.; Rolison, J.J.; Kane, J.; O’Neill, F.A.; Scarpa, R.; Kee, F. The Influence of Genotype Information on Psychiatrists’ Treatment Recommendations: More Experienced Clinicians Know Better What to Ignore. Value Health 2017, 20, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oestergaard, S.; Moldrup, C. Anticipated outcomes from introduction of 5-HTTLPR genotyping for depressed patients: An expert Delphi analysis. Public Health Genom. 2010, 13, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, R.G.; Bishop, J.R.; Elchynski, A.L.; Smith, D.M.; Rowe, E.; Blake, K.V.; Limdi, N.A.; Aquilante, C.L.; Bates, J.; Beitelshees, A.L.; et al. Best-worst scaling methodology to evaluate constructs of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Application to the implementation of pharmacogenetic testing for antidepressant therapy. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2022, 3, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishko, I.; Almeida, K.; Silvia, R.J.; Tataronis, G.R. Psychiatric pharmacists’ perception on the use of pharmacogenomic testing in the mental health population. Pharmacogenomics 2015, 16, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloat, N.T.; Yashar, B.M.; Ellingrod, V.L.; Ward, K.M. Assessing the impact of pre-test education on patient knowledge, perceptions, and expectations of pharmacogenomic testing to guide antidepressant use. J. Genet. Couns. 2022, 31, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomp, C.; Morris, E.; Edwards, L.; Hoens, A.M.; Landry, G.; Riches, L.; Ridgway, L.; Bryan, S.; Austin, J. Pharmacogenomic Testing for Major Depression: A Qualitative Study of the Perceptions of People with Lived Experience and Professional Stakeholders. Can. J. Psychiatry 2023, 68, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaiev, J.; Bergson, Z.; Sun, X.; Roy, D.; Desai, G.; Lencz, T.; Malhotra, A.; Zhang, J.-P. Patient Attitudes Toward Pharmacogenetic Testing in Psychiatric Treatment. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 10, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Hamilton, S.P.; Hippman, C. Psychiatrist attitudes towards pharmacogenetic testing, direct-to-consumer genetic testing, and integrating genetic counseling into psychiatric patient care. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 226, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuteja, S.; Salloum, R.G.; Elchynski, A.L.; Smith, D.M.; Rowe, E.; Blake, K.V.; Limdi, N.A.; Aquilante, C.L.; Bates, J.; Beitelshees, A.L.; et al. Multisite evaluation of institutional processes and implementation determinants for pharmacogenetic testing to guide antidepressant therapy. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undurraga, J.; Bórquez-Infante, I.; Crossley, N.A.; Prieto, M.L.; Repetto, G.M. Pharmacogenetics in Psychiatry: Perceived Value and Opinions in a Chilean Sample of Practitioners. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 657985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vest, B.M.; Wray, L.O.; Brady, L.A.; Thase, M.E.; Beehler, G.P.; Chapman, S.R.; Hull, L.E.; Oslin, D.W. Primary care and mental health providers’ perceptions of implementation of pharmacogenetics testing for depression prescribing. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, L.M.; Brandl, E.J.; Changasi, A.; Sturgess, J.E.; Soibel, A.; Notario, J.F.D.; Cheema, S.; Braganza, N.; Marshe, V.S.; Freeman, N.; et al. Physicians’ opinions following pharmacogenetic testing for psychotropic medication. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, S.; Carroll, J.C.; Jukic, S.; McGivney, M.S.; Klatt, P. Perspectives of a pharmacist-run pharmacogenomic service for depression in interdisciplinary family medicine practices. JACCP: J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 3, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, E.; Bhattacharya, D.; Sharma, R.; Wright, D.J. A Theory-Informed Systematic Review of Barriers and Enablers to Implementing Multi-Drug Pharmacogenomic Testing. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, J.; Curry, T.B.; Formea, C.M.; Nicholson, W.T.; Rohrer Vitek, C.R. Education and Knowledge in Pharmacogenomics: Still a Challenge? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas Kuželički, N.; Prodan Žitnik, I.; Gurwitz, D.; Llerena, A.; Cascorbi, I.; Siest, S.; Simmaco, M.; Ansari, M.; Pazzagli, M.; Di Resta, C.; et al. Pharmacogenomics education in medical and pharmacy schools: Conclusions of a global survey. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerligs, L.; Rankin, N.M.; Shepherd, H.L.; Butow, P. Hospital-based interventions: A systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation processes. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, J.; Nicoll, A.; Dimova, E.D.; Campbell, P.; Duncan, E.A. The barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainability of hospital-based interventions: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soueid, R.; Michael, T.J.F.; Cairns, R.; Charles, K.A.; Stocker, S.L. A Scoping Review of Pharmacogenomic Educational Interventions to Improve Knowledge and Confidence. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2024, 88, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Wang, M.Z.; Bates, J.; Shaddock, R.E.; Wiisanen, K. Pharmacogenomics education strategies in the United States pharmacy school curricula. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 16, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondrasek, A.; Fryza, A.; Aziz, M.A.; Leong, C.; Kowalec, K.; Maruf, A.A. Knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes toward pharmacogenomics among pharmacists and pharmacy students: A systematic review. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2015.

- Magavern, E.F.; Caulfield, M.J. Equal access to pharmacogenomics testing: The ethical imperative for population-wide access in the UK NHS. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 1701–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlinskiene, K.; Tomlinson, J.; Marques, I.; Richardson, S.; Stirling, K.; Petty, D. Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of new medicines into clinical practice: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.A.; Alsaidi, A.T.; Verbyla, A.; Cruz, A.; Macfarlane, C.; Bauer, J.; Patel, J.N. Cost Effectiveness of Pharmacogenetic Testing for Drugs with Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guidelines: A Systematic Review. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbelen, M.; Weale, M.E.; Lewis, C.M. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacogenetic-guided treatment: Are we there yet? Pharmacogenom. J. 2017, 17, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoulakis, V.; Koufaki, M.I.; Tzerefou, K.; Koufou, K.; Patrinos, G.P.; Mitropoulou, C. Assessing the utility of measurement methods applied in economic evaluations of pharmacogenomics applications. Pharmacogenomics 2024, 25, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafazoli, A.; Guchelaar, H.-J.; Miltyk, W.; Kretowski, A.J.; Swen, J.J. Applying Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms for Pharmacogenomic Testing in Clinical Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 693453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Shaaban, S. Interrogating Pharmacogenetics Using Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2024, 9, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopidogrel Genotype Testing after Ischaemic Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack [GID-DG10054]; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2023.

- Genedrive MT-RNR1 ID Kit for Detecting a Genetic Variant to Guide Antibiotic Use and Prevent Hearing Loss in Babies: Early Value Assessment; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2023.

- Newman, W.I.; Ingham, A.; McDermott, J. Study to Assess the Rollout of a Genetic-Guided Prescribing Service in UK General Practice: ISRCTN Registry. 2023. Available online: https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN15390784 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- McGuire, A.L.; Fisher, R.; Cusenza, P.; Hudson, K.; Rothstein, M.A.; McGraw, D.; Matteson, S.; Glaser, J.; Henley, D.E. Confidentiality, privacy, and security of genetic and genomic test information in electronic health records: Points to consider. Genet. Med. 2008, 10, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormondroyd, E.; Border, P.; Hayward, J.; Papanikitas, A. Genomic health data generation in the UK: A 360 view. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.A.; Davies, P.E.; Overall, C.C.; Grima, D.; Nam, J.; Dechairo, B.M. Cost-effectiveness of combinatorial pharmacogenomic testing for depression from the Canadian public payer perspective. Pharmacogenomics 2020, 21, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.-A.; Brown, L.C.; Yu, K.; Li, J.; Dechairo, B.M. Canadian Medication Cost Savings Associated with Combinatorial Pharmacogenomic Guidance for Psychiatric Medications. Clin. Outcomes Res. CEOR 2019, 11, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, M. An Overview of Co-Design: Advantages, Challenges and Perspectives of Users’ Involvement in the Design Process. J. Des. Think. 2021, 2, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, V.; House, A.; Hamer, S. Knowledge brokering: The missing link in the evidence to action chain? Evid. Policy 2009, 5, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, D. Pharmacogenomic testing pilot to start in general practice from June 2023. Pham. J. 2023, 310, 7973. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.S.; Damschroder, L.; Hagedorn, H.; Smith, J.; Kilbourne, A.M. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H.; Olswang, L. Is there a science to facilitate implementation of evidence-based practices and programs? Evid.-Based Commun. Assess. Interv. 2017, 11, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015, 350, h1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- College Report CR237—The Role of Genetic Testing in Mental Health Settings; Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2023.

- Duodecim. Schizophrenia—Valid Treatment Recommendation Helsinki 2022. The Working Group Established by Duodecim of the Finnish Medical Association and the Finnish Psychiatry Association. Available online: https://www.kaypahoito.fi/hoi35050?tab=suositus#s20 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Duodecim. Depression—Valid Treatment Recommendation. Working Group, Established by Duodecim of the Finnish Medical Association and the Finnish Psychiatry Association. Available online: https://www.kaypahoito.fi/hoi50023#s1 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- van Westrhenen, R.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; van Gelder, T.; Birkenhager, T.K.; Bakker, P.R.; Houwink, E.J.F.; Bet, P.M.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; van Weelden-Hulshof, M.J.M. Policy and Practice Review: A First Guideline on the Use of Pharmacogenetics in Clinical Psychiatric Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 640032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, A.A.; Aziz, M.A. The Potential Roles of Pharmacists in the Clinical Implementation of Pharmacogenomics. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Education England. Initial Education and Training of Pharmacists—Reform Programme. 2021. Available online: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/pharmacy/transforming-pharmacy-education-training/initial-education-training-pharmacists-reform-programme (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Middleton, A.; Taverner, N.; Moreton, N.; Rizzo, R.; Houghton, C.; Watt, C.; Horton, E.; Levene, S.; Leonard, P.; Melville, A.; et al. The genetic counsellor role in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roache, R. The biopsychosocial model in psychiatry: Engel and beyond. In Psychiatry Reborn: Biopsychosocial Psychiatry in Modern Medicine; Savulescu, J., Roache, R., Davies, W., Loebel, J.P., Davies, W., Savulescu, J., Roache, R., Loebel, J.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, W. Genetic Tests: Clinical Validity and Clinical Utility. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2014, 81, 9.15.1–9.15.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, N.; Frick, A.; Kopp, J.B. Genetic Testing in Clinical Settings. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 72, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strande, N.T.; Riggs, E.R.; Buchanan, A.H.; Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; Distefano, M.; Dwight, S.S.; Goldstein, J.; Ghosh, R.; Seifert, B.A.; Sneddon, T.P.; et al. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Gene-Disease Associations: An Evidence-Based Framework Developed by the Clinical Genome Resource. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demkow, U.; Wolańczyk, T. Genetic tests in major psychiatric disorders—Integrating molecular medicine with clinical psychiatry—Why is it so difficult? Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, A.; Tomlinson, J.; Medlinskiene, K.; Howard, D.; Saeed, I.; Sohal, J.; Dalton, C.; Sagoo, G.S.; Cardno, A.; Bristow, G.C.; et al. What are the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of pharmacogenomics in mental health settings? A theory-based systematic review. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 32 (Suppl. 1), i22–i23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coherence | Cognitive Participation | Collection Action | Reflexive Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1—Differentiation: sense-making work that is carried out to understand how PGx practices and the PGx approach is different from standard prescribing | 2.1—Initiation: relational work people do to drive forward the use of PGx practices | 3.1—Interactional Workability: work that people do with each other, objects and factors relating PGx when operationalising in practice | 4.1—Systematisation: work of stakeholders in collecting information about PGx to determine how useful it is for themselves and others |

| 1.2—Communal Specification: sense-making work that people do together to build a shared understanding of the aims, objectives, and potential benefits of PGx | 2.2—Enrolment: work involved in reorganising people, their individual and group relationships, to collectively contribute to the use of PGx | 3.2—Relational Integration: knowledge work that people do to build accountability and maintain confidence in PGx and others as they use it | 4.2—Communal Appraisal: the work that people do collectively to evaluate the worth of PGx in practice |

| 1.3—Individual Specification: sense-making work people do individually to understand the tasks and responsibilities relating to PGx expected of them | 2.3—Legitimation: relational work that people do to ensure that others believe they are right to be involved in PGx and that they can contribute to its use in practice | 3.3—Skill Set Workability: allocation work to divide the labour of PGx and related work, as PGx is operationalised in practice, based on individual and group skills and knowledge | 4.3—Individual Appraisal: work people do individually to appraise how PGx impacts on them and their work contextually, to express their personal relationship to PGx |

| 1.4—Internalisation: sense-making work people do to understand the worth of PGx, including its value, benefits, and importance | 2.4—Activation: work that people do to collectively define the actions and processes required to sustain PGx use | 3.4—Contextual Integration: resource work carried out to allocate resources, and execute policies, procedures and protocols to initiate the use of PGx in practice | 4.4—Reconfiguration: appraisal work people do to redefine or modify PGx practices or procedures |

| PICOS Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Population | Healthcare professionals working in mental health settings OR patients with a psychiatric disorder cared for by mental health care providers. |

| Intervention | The use of PGx Testing during prescribing of a psychotropic medicine. |

| Comparison | * Not applicable. |

| Outcome | Primary qualitative or quantitative data collected pre-, post-, or during PGx implementation, in the context of psychotropic prescribing. |

| Study Type | Qualitative or quantitative studies |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

| Author and Year | Aims | Design, Methods, and Country | Study Setting and Participants | Funding Source and Conflicts of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboelbaha, 2023 [62] | To explore the knowledge, level of engagement, and perspectives on the use of PGx testing when making depression management decisions among practicing psychiatrists in the MENA region | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Jordan, Egypt, Tunisia, Oman, Palestine, Iraq, Kuwait, UAE, Algeria | Mental health settings— specifically depression management Psychiatrists | No conflicts of interest were declared by the authors. Funding was via open-access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. |

| Almeida, 2021 [63] | To assess the perception and knowledge of PGx among Brazilian psychiatrists | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey Brazil | Clinical setting not specified Psychiatrists | No conflicts of interest were declared. Lead author is a recipient of a public scholarship, but the research did not receive any specific grant funding. |

| Barr, 2008 [64] | To explore the range of factors that may impinge upon public and service user acceptability of the pharmacogenomics of antidepressants | Qualitative Focus Groups England, Poland, Germany, Denmark | Mental health settings— specifically depression clinics Patients General Public | The research project was funded by the European Commission. No statement on conflicts of interest stated included. |

| Bousman, 2022 [65] | To explore the perceptions toward PGx testing among members of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey USA | Inpatient and outpatient geriatric settings Psychiatrists | Conflicts of interest declared by some authors, with some in receipt of a range of public and private funding. |

| Chan, 2017 [66] | To assess the attitudes and opinions of clinicians in psychiatry in Singapore towards pharmacogenomic testing, and in doing so elicit its possible barriers and risks to employ this technology in patient care | Qualitative and Quantitative Web-based survey Singapore | Public and private mental health settings Psychiatrists Pharmacists | No conflicts of interest declared by authors. Study was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council. |

| Dunbar, 2012 [67] | To explore experiences of ordering, receiving, and utilizing the AmpliChip® CYP450 test results, as well as the perceived advantages and disadvantages of employing the test in practice. | Qualitative Interviews New Zealand | Secondary care mental health settings Psychiatry doctors | No conflicts of interest statement included. The study was funded by Roche Diagnostics, through an unrestricted research grant, with 100 of the AmpliChip CYP450 tests being made available free of charge. |

| Gainey, 2017 [68] | To evaluate mental health clinicians’ perceived knowledge regarding pharmacogenetic testing, their attitude, receptivity towards, and confidence in pharmacogenetic testing, and how pharmacogenetic testing is being implemented to support precision medicine in outpatient clinics | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews USA | Outpatient mental health clinics Nurse Practitioners, Clinical Nurse Specialists, Physician Assistants Medical Doctors (certified in psychiatry) | Dissertation completed in fulfilment of a PhD. No conflicts of interest or funding statements provided. |

| Goodspeed, 2019 [69] | To evaluate input from mental health clinicians on electronic health record integrated clinical decision support (CDS) tool and PGx, and the reactions of psychiatry clinicians to a CDS prototype | Qualitative Focus Group USA | Clinical setting not specified Doctors Nurses (That had psychiatry certification) | The study was funded through a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Several authors are or were employees of RxRevu, a for-profit healthcare information technology company. |

| Hahn, 2023 [70] | To identify barriers to implementation of PGx in Germany, to identify why implementation has been slower in other countries | Quantitative Questionnaire Germany | Inpatient depression clinics Patients | |

| Hoop, 2008 [71] | To investigate the attitudes of a random national sample of psychiatrists about the likely impact of genetic testing on psychiatric patients and the field | Quantitative Survey USA | Mix of clinical settings—inpatient and outpatient psychiatric settings, both public and private Psychiatrists | Funding from the National Institutes of Health declared. No conflicts of interest statement included. |

| Hoop, 2010 [72] | To systematically assess attitudes and experiences of psychiatrists regarding the role and key clinical/ethical issues relevant to Pharmacogenetic Testing in psychiatry | Qualitative and Quantitative Survey USA | Academic medical centres with Departments of Psychiatry Psychiatrists Psychiatry Residents | No conflicts of interest reported by authors. Funding declared from the ‘Research for a Healthier Tomorrow-Program Development Fund’. |

| Kastrinos, 2020 [73] | To understand what psychiatry patients already know about the use of PGx in psychiatry and their interest in participating in testing. | Quantitative Questionnaire USA | Clinical setting not specified Patients | Research supported by a National Institute for Health award. No conflicts of interest statement included. |

| Kung, 2011 [74] | To explore patient and clinician satisfaction with Pharmacogenetic Testing | Quantitative Survey USA | Inpatient psychiatry Clinicians Patients | One author is an employee of AssureRx, a personalised medicine company, but not at the time of the study. AssureRx also provided genotyping testing as part of this study. |

| Laplace, 2021 [75] | To evaluate the acceptability of PGxT by psychiatrists and psychiatry residents in France using a four domains acceptability model based on International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) and Nielsen models (usefulness, usability, easiness, and risk). | Quantitative Survey France | Mix of clinical settings—both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, including adult, geriatric, child and adolescent, substance misuse and forensic psychiatry Psychiatrists Psychiatry Residents | No external funding was received to conduct the research. Authors reported no conflicts of interest. |

| Liko, 2020 [76] | To assess patients’ perspectives and experiences with psychiatric pharmacogenetic testing | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews USA | Outpatient psychiatry— depression Clinic Patients | No conflicts of interest reported by authors. No statement about the funding of research. |

| McCarthy, 2020 [77] | To assess motivations, attitudes, and concerns about PGxT in a cohort of depressed veteran patients with past drug treatment failure indicating some degree of treatment resistance using the MAPP instrument | Quantitative Questionnaire USA | Secondary Care Psychiatry Patients | Funded through an award from the National Institutes for Health. No conflicts of interest declared by authors. |

| McMichael, 2017 [78] | To contribute to the topical issue of whether genotype information influences the treatment recommendations of psychiatrists when a patient’s treatment response (in terms of symptom improvement) is already known to the psychiatrist. | Quantitative Choice-format conjoint analysis (discrete choice experiment) Northern Ireland | Clinical setting not specified Psychiatrists | No conflicts of interest reported by authors. Financial support declared and was provided through a grant from the Department of Education and Learning. |

| Oestergaard, 2010 [79] | To provide expert perspectives regarding the extent to which the introduction of 5-HTTLTR pretesting in clinical practice as a routine procedure would lead to better clinical outcomes | Qualitative and Quantitative Delphi Method Not Specified | Clinical setting not specified Experts in 5-HTTLPR genotyping (doctors and pharmacists) | No conflicts of interest or funding statements included in the paper. |

| Salloum, 2022 [80] | Using a BWS experiment to evaluate the importance of implementation factors for PGx testing to guide antidepressant prescribing | Quantitative Best Worse Scaling Survey USA | Clinical setting not specified—participating organisations were funded and affiliate members of the IGNITE Network (a multidisciplinary consortium focused on the development, implementation, and dissemination of methods that integrate genomic medicine into clinical care) Individual participant’s roles not specified | Some authors reported a combination of funding and associations with private and public organisations. Research in the publication was funded through several research grants from a variety of public organisations and institutions. |

| Shishko, 2015 [81] | Evaluate psychiatric pharmacists use, knowledge, and perception of the effectiveness of PGx testing | Quantitative Cross-sectional survey USA, Canada, Abu Dhabi, Indonesia, Singapore | Mix of clinical settings—inpatient and outpatient settings, both public and private, and community pharmacy Psychiatric Pharmacists | No conflicting interests were reported by the authors and no industry funding was used in the research. |

| Sloat, 2022 [82] | To assess perspectives of patients with depression on PGxT for depression management and study the impact of an educational intervention for this population | Quantitative Case–control survey study USA | Clinical setting not specified Patients | University funding declared. Authors reported no conflicts of interest. |

| Slomp, 2022 [83] | To explore the perceptions if PGxT among PWLE and P/HCP to inform the process of considering the clinical implementation of PGxT for depression within the healthcare system in British Colombia (BC), Canada. | Qualitative Semi-structured interview Canada | Clinical setting not specified People with lived experience (PWLE) Professional stakeholders (clinicians, laboratory staff, insurance representatives, and policy makers) | Authors reported no conflicts of interest. Public award funding was declared. |

| Tamaeiev, 2023 [84] | To learn more about psychiatric patients’ attitudes towards PGx | Quantitative Survey USA | Inpatient and outpatient psychiatric Settings Patients Patient family members | Some authors reported conflicts of interest with affiliations to Genomind Inc and InformedDNA. Several authors declared public funding through the National Institutes for Health. |

| Thompson, 2015 [85] | To assess attitudes towards integration of genetic counselling into psychiatric patient care, specifically in the context of the use of pharmacogenomic test results to guide treatment. | Quantitative Cross-sectional questionnaire study USA | Inpatient and outpatient psychiatric settings Psychiatrists Psychiatry residents | Authors reported no conflicts of interest. Funding came through a gift donation and a grant from the National Society of Genetic Counselor’s Psychiatry Special Interest Group. |

| Tuteja, 2022 [86] | To understand factors important for the implementation of PGxT to guide antidepressant prescribing | Quantitative Survey USA | Clinical setting not specified—17 sites that had either implemented PGx or were planning to | Research was supported through funding from a range of public funding bodies, mainly the National Institutes for Health. Several authors reported affiliations to or funding from private organisations. |

| Undurraga, 2021 [87] | To explore opinions about current practices, perceived value, and barriers to clinical use of PGxT amongst Chilean psychiatrists | Quantitative Survey Chile | Mix of clinical settings—including child, adolescent, and adult psychiatry settings in both public, private, and academic sectors Psychiatrists | Funding was provided by public agencies. The research was conducted in absence of any commercial or financial conflicts of interest. |

| Vest, 2020 [88] | To understand providers’ perspectives of PGx for antidepressant prescribing and implications for future implementation | Qualitative Focus Groups USA | Outpatient psychiatric clinics and primary care clinics Psychiatrists Primary Care Providers (Internists, Family Medicine, Advanced Nurse Practitioners) | Myriad Genetics provided in-kind testing for the study. Funding reported from a range of public organisations. A range of affiliations to different commercial and private organisations declared by one author. |

| Walden, 2015 [89] | To explore physicians’ opinions of PGxT and their experiences using PGxT for psychotropic medication | Quantitative Survey Canada | Mix of clinical settings—psychiatric and primary care settings Psychiatrists General Practitioners | Author funding reported from a variety of public organisations. One author reported affiliations with private companies |

| Weinstein, 2020 [90] | To explore physicians’ and pharmacist stakeholder perceptions on implementing a pharmacist-run pharmacogenomic service for patients with depression in a primary care setting | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews USA | Primary care outpatient family medicine practices Pharmacists Family Medicine Physicians | Funding through a grant from the Pennsylvania Pharmacists Association Educational Foundation. No conflicts of interest reported. |

| NPT | Barriers | Facilitators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Coherence | ||||

| 1.1 Differentiation | HP | Fear PGxT may replace (rather than complement) existing prescribing practices [62,67,68] | B | Perception that PGx offers an improved approach to prescribing [62,64,88] |

| Pa | Perception that PGxT is an extension of the medical model of psychiatry [64] | B | ||

| B |

| |||

| 1.2 Communal Specification | B | Lack of consensus about purpose and potential benefits of PGxT [65,67,75,81,87] | B | Perception that PGx is a tool to help guide prescribing and support clinical decisions to improve prescribing outcomes [62,63,67,68,72,75,76,77,79,81,83,84,89] |

| HP | B | |||

| Pa | Pa | Additional information and counselling given to patients during PGxT helps feel more informed about their medication and illness [68,77,84] | ||

| 1.3 Individual Specification | HP | Lack of understanding about what PGxT entails and requires of them [66,67,68,81,87] | HP | Experience helped stakeholders understand what PGx requires of them [65,68] |

| B | Patient lack of awareness about what PGxT is [68,70,73,74,75,82,84] | HP |

| |

| Pa | Patient understanding of PGxT involves for them may fluctuate based on mental health status [64] | HP | Prescribers believed not acting on or using PGx results would not cause liability issues [65] | |

| 1.4 Internalisation | B | Belief that PGx currently lacks evidence to support clinical utility, specifically for: [62,65,72,79,87,88] | B | Perception that PGx has a range of potential HCP, individual, and system benefits and values: [62,63,81,83,84,87,88] |

| HP | HP | |||

| HP | B | |||

| B |

| B | ||

| B | Concern that PGxT may cause harm or distress [63,65,66,67,68,71,72,75,77,83] | HP | Belief that PGx can help engage patients in shared decision making [67,68,69,85] | |

| HP | B | Agreement that PGx can reassure patients by reducing uncertainty about taking a medicine [67,68,69,73,83,84] | ||

| B | HP |

| ||

| B | Perception that PGxT is not cost-effective [68,76,81] | B | PGx can validate previous medication experiences [67,68,76,83,87,88] | |

| 2. Cognitive Participation | ||||

| 2.1 Initiation | Ps | Some psychiatrists do not believe they are appropriate to drive implementation, in part due to: | B | Strong interest in adopting PGxT, due to belief it will yield patient, HCP, and system benefits [62,65,66,72,73] |

| Ps | HP | Belief that pharmacists are important in PGx implementation [62,68,90] | ||

| Ps |

| HP | MDT approach to monitoring PGx outcomes is desired [86,90] | |

| 2.2 Enrolment | B | Perceived difficulty to integrate PGx into existing clinical pathways and services [69,70,88] | HP | Willingness from psychiatrists and prescribers to engage with other HCPs during implementation, particularly [68,86,90]: |

| Ph | ||||

| HP | ||||

| HP | Trust is key when HCPs collaborate on PGx [69,90] | |||