Patient Perceptions of Paramedian Minimally Invasive Spine Skin Incisions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Survey Methods

2.3. Incision Research

- (1)

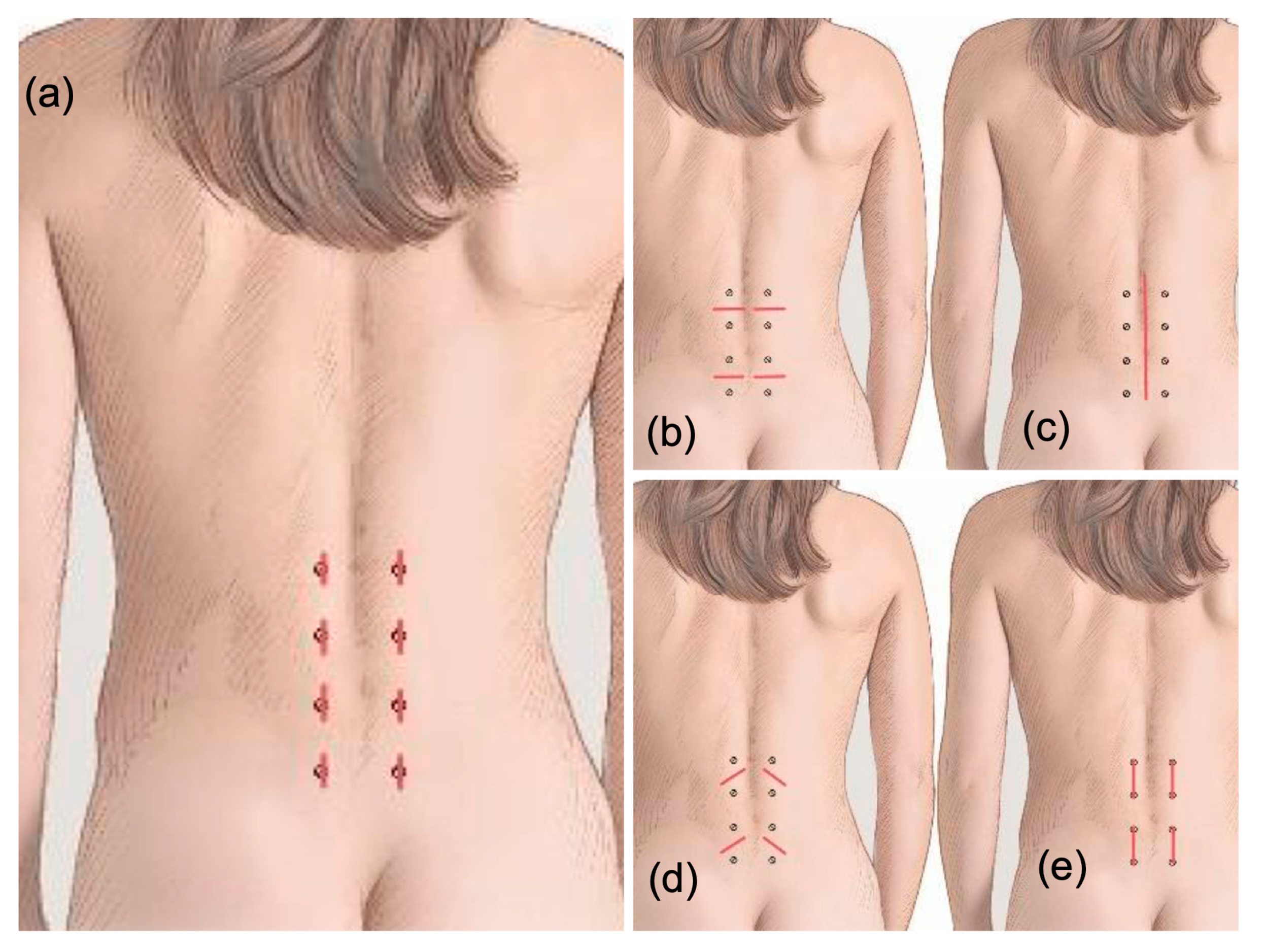

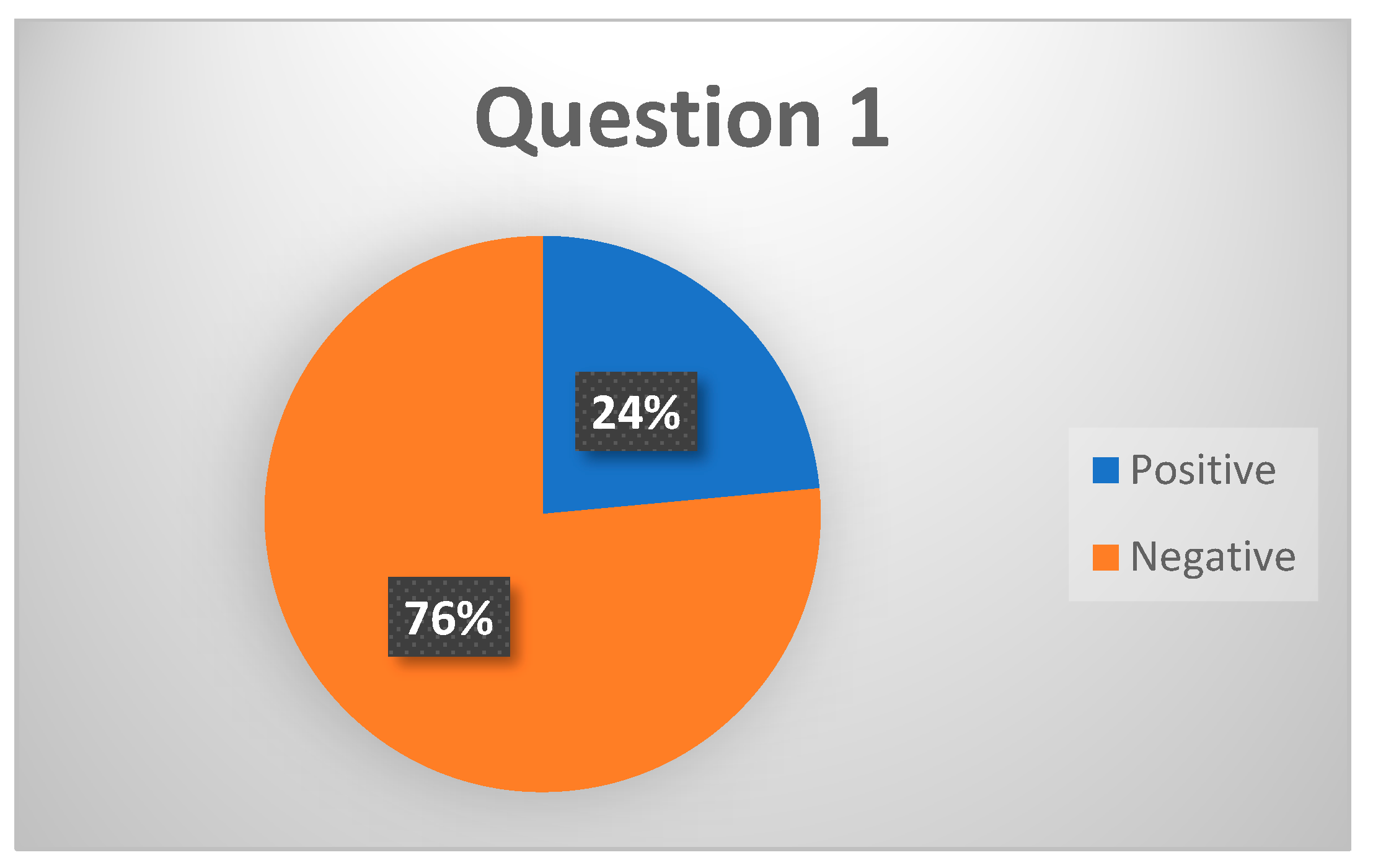

- Can you describe your first impression when you see the incisions that could be on your back after spine surgery? (As shown in Figure 1 a comment section was provided.)

- (2)

- How much do you worry about how the incision on your back looks? (Likert scale from 1–5 stars; ✰✰✰✰✰).

- (3)

- Which of the following comes to mind if you had a choice of a skin incision on your back?

- a.

- I prefer a midline skin incision;

- b.

- I want the least number of skin incisions possible;

- c.

- I am more worried that I have less pain;

- d.

- I am more concerned with my surgeon being able to do a good job.

- (4)

- Please rate how this incision appeals to you? Figure 2a.

- (5)

- Please rate how this incision appeals to you? Figure 2d.

- (6)

- Please rate how this incision appeals to you? Figure 2e.

- (7)

- Please rate how this incision appeals to you? Figure 2b.

- (8)

- Which of the four incisions would you prefer? Figure 2a,b,d,e.

- (9)

- Please tell us anything about your incision from spine surgery!

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mooney, J.; Michalopoulos, G.D.; Alvi, M.A.; Zeitouni, D.; Chan, A.K.; Mummaneni, P.V.; Bisson, E.F.; Sherrod, B.A.; Haid, R.W.; Knightly, J.J.; et al. Minimally invasive versus open lumbar spinal fusion: A matched study investigating patient-reported and surgical outcomes. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2021, 36, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; White, C.A.; Arvind, V.; Cho, S.; Kim, J.S.; Steinberger, J. What Are Patients Saying About Minimally Invasive Spine Surgeons Online: A Sentiment Analysis of 2235 Physician Review Website Reviews. Cureus 2022, 14, e24113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terai, H.; Tamai, K.; Kaneda, K.; Omine, T.; Katsuda, H.; Shimada, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nakamura, H. Postoperative Physical Therapy Program Focused on Low Back Pain Can Improve Treatment Satisfaction after Minimally Invasive Lumbar Decompression. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.C.B.; Patel, M.R.B.; Park, G.A.B.; Gheewala, J.R.B.; Vanjani, N.N.B.; Pawlowski, H.B.; Prabhu, M.C.B.; Singh, K. The Influence of Presenting Physical Function on Postoperative Patient Satisfaction and Clinical Outcomes Following Minimally Invasive Lumbar Decompression. Clin. Spine Surg. 2023, 36, E6–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekhail, N.; Costandi, S.; Abraham, B.; Samuel, S.W. Functional and patient-reported outcomes in symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis following percutaneous decompression. Pain Pract. 2012, 12, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.W.; Loke, A.Y. Factors and concerns of patients that influence the decision for spinal surgery and implications for practice: A review of literature. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 2017, 25, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brintz, C.E.; Coronado, R.A.; Schlundt, D.G.; Jenkins, C.H.; Bird, M.L.; Bley, J.A.; Pennings, J.S.; Wegener, S.T.; Archer, K.T. A Conceptual Model for Spine Surgery Recovery: A Qualitative Study of Patients’ Expectations, Experiences, and Satisfaction. Spine 2022, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Sturiale, C.L.; Pucci, R.; Reale, G.; Stifano, V.; Izzo, A.; Perna, A.; Proietti, L.; Forcato, S.; Perla, K.M.R.; et al. Patient-Oriented Aesthetic Outcome After Lumbar Spine Surgery: A 1-Year Follow-Up Prospective Observational Study Comparing Minimally Invasive and Standard Open Procedures. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, e1041–e1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.M.; Schpero, W.L.; Casalino, L.P.; Zhang, M.; Khullar, D. Association Between Individual Primary Care Physician Merit-based Incentive Payment System Score and Measures of Process and Patient Outcomes. JAMA 2022, 328, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabianlou Korth, M.J.; Lu, L.Y.; Finlay, A.K.; Kamal, R.N.; Goodman, S.B.; Maloney, W.J.; Amanatullah, D.F.; Huddleston, J.I. A Physician Assistant Is Associated with Higher Patient Satisfaction with Outpatient Orthopedic Surgery. Orthopedics 2022, 45, e252–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, K. On the anatomy and physiology of the skin. I. the cleavability of the cutis. Br. J. Plast Surg. 1861, 31, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobbs, R.J.; Sivabalan, P.; Li, J. Technique, challenges and indications for percutaneous pedicle screw fixation. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 18, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.R.; Clark, A.J.; Lee, S.L.; Venable, G.T.; Rossi, N.B.; Foley, K.T. Surgical Outcomes for Minimally Invasive vs Open Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 847–874, discussion 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaganesan, A.; Hirsch, B.; Phillips, F.M.; McGirt, M.J. Spine Surgery in the Ambulatory Surgery Center Setting: Value-Based Advancement or Safety Liability? Neurosurgery 2018, 83, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubelski, D.; Senol, N.; Silverstein, M.P.; Alvin, M.D.; Benzel, E.C.; Mroz, T.E.; Schlenk, R. Quality of life outcomes after revision lumbar discectomy. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2015, 22, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouknaitir, J.B.; Carreon, L.Y.; Brorson, S.; Pedersen, C.F.; Andersen M, Ø. Wide Laminectomy, Segmental Bilateral Laminotomies, or Unilateral Hemi-Laminectomy for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Five-year Patient-reported Outcomes in Propensity-matched Cohorts. Spine 2021, 46, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, S.; Goldstein, J.A. Minimally invasive versus open spine surgery: What does the best evidence tell us? J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2017, 8, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebl, D. Minimally invasive spine surgery. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet Med. 2017, 10, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, W.; Aladdin, M.; Almuammar, S.; Gari, D. Comparative Study of 2 Skin Incisions for Microscopic Lumbar Discectomy. World Neurosurg. 2017, 100, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencle, F.J.; Seale, J.A.; Benny, A.; Salomon, S.; Simela, A.; Chin, K.R. Option for transverse midline incision and other factors that determine patient’s decision to have cervical spine surgery. J. Orthop. 2018, 15, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deck, M.; Kopriva, D. Patient and observer scar assessment scores favour the late appearance of a transverse cervical incision over a vertical incision in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy for stroke risk reduction. Can. J. Surg. 2015, 58, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, A.F.; Ziolkowski, N.; Mundy, L.R.; Miller, H.C.; McIlvride, A.; DiLaura, A.; Fish, J.; Pusic, A. Development of a New Patient-reported Outcome Instrument to Evaluate Treatments for Scars: The SCAR-Q. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2018, 6, e1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decety, J. The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Dev. Neurosci. 2010, 32, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Li, X.; Peng, W.; Li, Z.; Shen, L. The interaction between pain and attractiveness perception in others. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ghadeer, H.A.; AlAlwan, M.A.; AlAmer, M.A.; Alali, F.J.; Alkhars, G.A.; Alabdrabulrida, S.A.; Al Shabaan, H.R.; Buhlaigah, A.M.; AlHewishel, M.A.; Alabdrabalnabi, H.A. Impact of Self-Esteem and Self-Perceived Body Image on the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery. Cureus 2021, 13, e18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundy, L.R.; Miller, H.C.; Klassen, A.F.; Cano, S.J.; Pusic, A.L. Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments for Surgical and Traumatic Scars: A Systematic Review of their Development, Content, and Psychometric Validation. Aesthetic. Plast. Surg. 2016, 40, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelli, S.; Ferriero, G.; Sartorio, F.; Stissi, V.; Franchignoni, F. How to assess postsurgical scars: A review of outcome measures. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quiring, K.; Lorio, M.P.; León, J.F.R.; de Carvalho, P.S.T.; Fiorelli, R.K.A.; Lewandrowski, K.-U. Patient Perceptions of Paramedian Minimally Invasive Spine Skin Incisions. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13060878

Quiring K, Lorio MP, León JFR, de Carvalho PST, Fiorelli RKA, Lewandrowski K-U. Patient Perceptions of Paramedian Minimally Invasive Spine Skin Incisions. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(6):878. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13060878

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuiring, Kimberly, Morgan P. Lorio, Jorge Felipe Ramírez León, Paulo Sérgio Teixeira de Carvalho, Rossano Kepler Alvim Fiorelli, and Kai-Uwe Lewandrowski. 2023. "Patient Perceptions of Paramedian Minimally Invasive Spine Skin Incisions" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 6: 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13060878

APA StyleQuiring, K., Lorio, M. P., León, J. F. R., de Carvalho, P. S. T., Fiorelli, R. K. A., & Lewandrowski, K.-U. (2023). Patient Perceptions of Paramedian Minimally Invasive Spine Skin Incisions. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(6), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13060878