Clinical Presentation Is Dependent on Age and Calendar Year of Diagnosis in Celiac Disease: A Hungarian Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Site, Data Sources and Data Collections

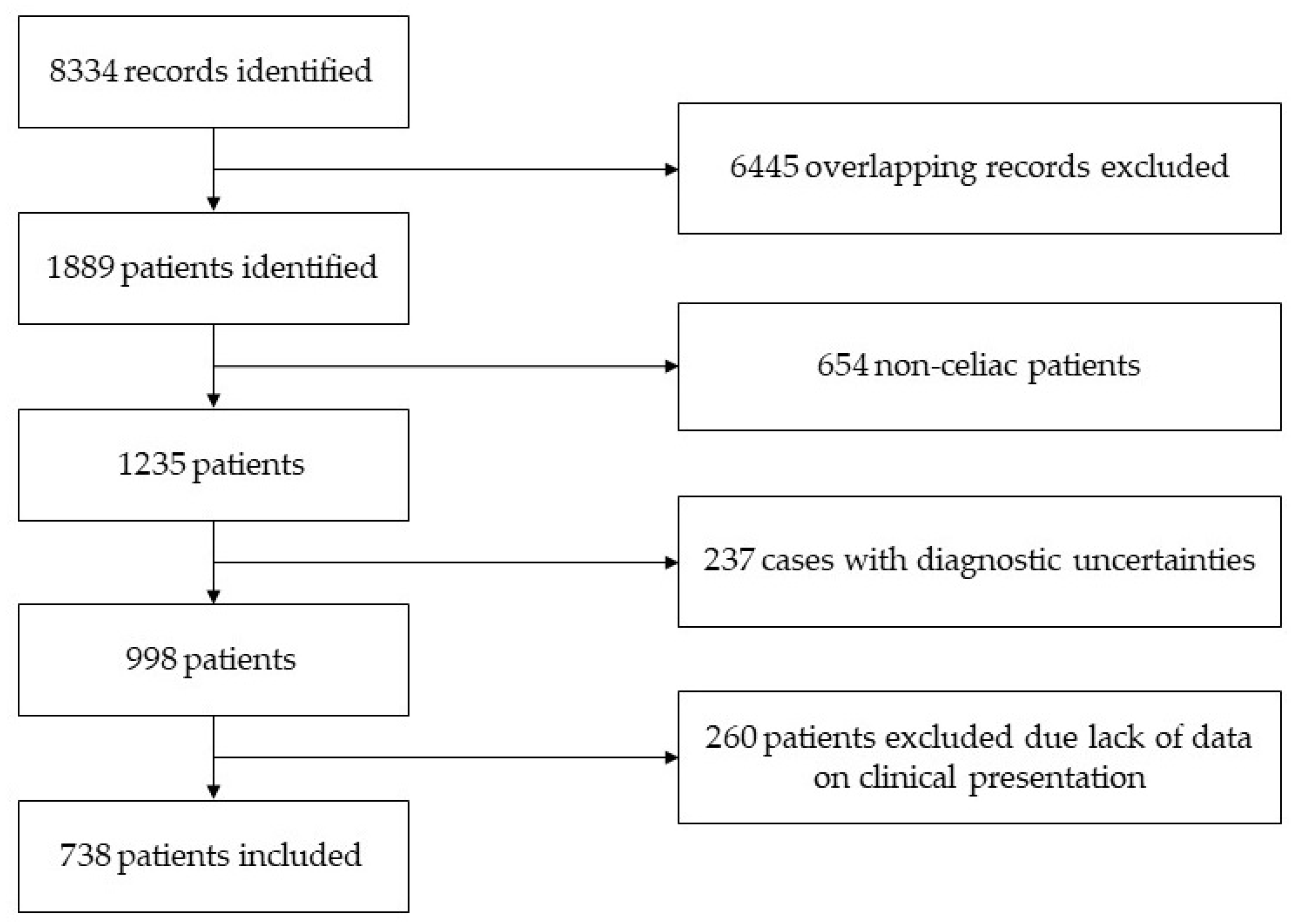

2.2. Study Population, Eligibility and Clinical Phenotype

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Catassi, C.; Verdu, E.F.; Bai, J.C.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makharia, G.K.; Singh, P.; Catassi, C.; Sanders, D.S.; Leffler, D.; Ali, R.A.R.; Bai, J.C. The global burden of coeliac disease: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egberg, M.D. Taking a “Second Look” at the Incidence of Pediatric Celiac Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 461–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Kong, W.J.; Feng, Y.; Lu, J.J.; Hui, W.J.; Liu, W.D.; Li, Z.Q.; Shi, T.; Cui, M.; Sun, Z.Z.; et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and histological presentation of celiac disease in Northwest China. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, T.; Ihara, K. Celiac Disease Genetics, Pathogenesis, and Standard Therapy for Japanese Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, H. Japanese Pediatricians and Celiac Disease. Pediatr. Int. 2023, e15509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujoel, I.A.; Reilly, N.R.; Rubio-Tapia, A. Celiac Disease: Clinical Features and Diagnosis. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 48, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A. Clinical presentation of celiac disease in the pediatric population. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, S68–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.H. The many faces of celiac disease: Clinical presentation of celiac disease in the adult population. Gastroenterology 2005, 128 (Suppl. S1), S74–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, M.; Ferro, A.; Brascugli, I.; Mattivi, S.; Fagoonee, S.; Pellicano, R. Extra-Intestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease: What Should We Know in 2022? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauli, D.; Grassi, A.; Granito, A.; Foderaro, S.; De Franceschi, L.; Ballardini, G.; Bianchi, F.B.; Volta, U. Prevalence of silent coeliac disease in atopics. Dig. Liver Dis. 2000, 32, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, U.; Granito, A.; De Franceschi, L.; Petrolini, N.; Bianchi, F.B. Anti tissue transglutaminase antibodies as predictors of silent coeliac disease in patients with hypertransaminasaemia of unknown origin. Dig. Liver Dis. 2001, 33, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loberman-Nachum, N.; Schvimer, M.; Avivi, C.; Barshack, I.; Lahad, A.; Fradkin, A.; Bujanover, Y.; Weiss, B. Relationships between Clinical Presentation, Serology, Histology, and Duodenal Deposits of Tissue Transglutaminase Antibodies in Pediatric Celiac Disease. Dig. Dis. 2018, 36, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taavela, J.; Kurppa, K.; Collin, P.; Lähdeaho, M.L.; Salmi, T.; Saavalainen, P.; Haimila, K.; Huhtala, H.; Laurila, K.; Sievänen, H.; et al. Degree of damage to the small bowel and serum antibody titers correlate with clinical presentation of patients with celiac disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2013, 11, 166–171.e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, S.; Kurppa, K.; Repo, M.; Huhtala, H.; Kaukinen, K.; Lindfors, K.; Arvola, T.; Kivelä, L. Severity of Villous Atrophy at Diagnosis in Childhood Does Not Predict Long-term Outcomes in Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciclitira, P.J. Does clinical presentation correlate with degree of villous atrophy in patients with celiac disease? Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 4, 482–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, C.; Cirillo, M.; Sollazzo, R.; Savino, G.; Sabbatini, F.; Mazzacca, G. Gender and clinical presentation in adult celiac disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1995, 30, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, M.; Sbravati, F.; Allegri, D.; Labriola, F.; Lombardo, V.; Spisni, E.; Zarbo, C.; Alvisi, P. Is the clinical pattern of pediatric celiac disease changing? A thirty-years real-life experience of an Italian center. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkerman, M.; Tan, I.L.; Kolkman, J.J.; Withoff, S.; Wijmenga, C.; Visschedijk, M.C.; Weersma, R.K. A large variety of clinical features and concomitant disorders in celiac disease—A cohort study in the Netherlands. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez Castro, P.; Harkin, G.; Hussey, M.; Christopher, B.; Kiat, C.; Liong Chin, J.; Trimble, V.; McNamara, D.; MacMathuna, P.; Egan, B.; et al. Changes in Presentation of Celiac Disease in Ireland From the 1960s to 2015. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2017, 15, 864–871.e863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandimarte, G.; Tursi, A.; Giorgetti, G.M. Changing trends in clinical form of celiac disease. Which is now the main form of celiac disease in clinical practice? Minerva Gastroenterol. E Dietol. 2002, 48, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Steens, R.F.; Csizmadia, C.G.; George, E.K.; Ninaber, M.K.; Hira Sing, R.A.; Mearin, M.L. A national prospective study on childhood celiac disease in the Netherlands 1993–2000: An increasing recognition and a changing clinical picture. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapsas, D.; Hollén, E.; Stenhammar, L.; Fälth-Magnusson, K. The clinical presentation of coeliac disease in 1030 Swedish children: Changing features over the past four decades. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzini, A.; Villanacci, V.; Apillan, N.; Lanzarotto, F.; Pirali, F.; Amato, M.; Indelicato, A.; Scarcella, C.; Donato, F. Epidemiological, clinical and histopathologic characteristics of celiac disease: Results of a case-finding population-based program in an Italian community. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 40, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Murray, J.A.; Katzka, D.A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Monitoring of Celiac Disease-Changing Utility of Serology and Histologic Measures: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Hill, I.D.; Kelly, C.P.; Calderwood, A.H.; Murray, J.A. ACG clinical guidelines: Diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 656–676, quiz 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiteri, A.; Granito, A.; Giamperoli, A.; Catenaro, T.; Negrini, G.; Tovoli, F. Current guidelines for the management of celiac disease: A systematic review with comparative analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Hill, I.D.; Semrad, C.; Kelly, C.P.; Lebwohl, B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines Update: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakács, Z.; Csiszár, B.; Nagy, M.; Farkas, N.; Kenyeres, P.; Erős, A.; Hussain, A.; Márta, K.; Szentesi, A.; Tőkés-Füzesi, M.; et al. Diet-Dependent and Diet-Independent Hemorheological Alterations in Celiac Disease: A Case-Control Study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajor, J.; Szakács, Z.; Juhász, M.; Papp, M.; Kocsis, D.; Szegedi, É.; Földi, I.; Farkas, N.; Hegyi, P.; Vincze, Á. HLA-DQ2 homozygosis increases tTGA levels at diagnosis but does not influence the clinical phenotype of coeliac disease: A multicentre study. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2019, 46, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, E.; Panayiotou, J.; Karantana, H.; Constantinidou, C.; Siakavellas, S.I.; Krini, M.; Syriopoulou, V.P.; Bamias, G. Changing pattern in the clinical presentation of pediatric celiac disease: A 30-year study. Digestion 2009, 80, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almallouhi, E.; King, K.S.; Patel, B.; Wi, C.; Juhn, Y.J.; Murray, J.A.; Absah, I. Increasing Incidence and Altered Presentation in a Population-based Study of Pediatric Celiac Disease in North America. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauthammer, A.; Guz-Mark, A.; Zevit, N.; Marderfeld, L.; Waisbourd-Zinman, O.; Silbermintz, A.; Mozer-Glassberg, Y.; Nachmias Friedler, V.; Rozenfeld Bar Lev, M.; Matar, M.; et al. Age-Dependent Trends in the Celiac Disease: A Tertiary Center Experience. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, U.; Caio, G.; Stanghellini, V.; De Giorgio, R. The changing clinical profile of celiac disease: A 15-year experience (1998-2012) in an Italian referral center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, S. Changing Clinical Manifestations of Celiac Disease in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 63, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Kapoor, S.; Dubey, A.P. Celiac disease presentation in a tertiary referral centre in India: Current scenario. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 32, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, P.; Thapa, B.R.; Nain, C.K.; Prasad, K.K.; Singh, K. Changing spectrum of celiac disease in India. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2010, 20, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Zingone, F.; West, J.; Auricchio, R.; Maria Bevilacqua, R.; Bile, G.; Borgheresi, P.; Erminia Bottiglieri, M.; Caldore, M.; Capece, G.; Cristina Caria, M.; et al. Incidence and distribution of coeliac disease in Campania (Italy): 2011–2013. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2015, 3, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Toma, A.; Volta, U.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Sanders, D.S.; Cellier, C.; Mulder, C.J.; Lundin, K.E.A. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 583–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telega, G.; Bennet, T.R.; Werlin, S. Emerging new clinical patterns in the presentation of celiac disease. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008, 162, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauthammer, A.; Guz-Mark, A.; Zevit, N.; Marderfeld, L.; Waisbourd-Zinman, O.; Silbermintz, A.; Mozer-Glassberg, Y.; Nachmias Friedler, V.; Rozenfeld Bar Lev, M.; Matar, M.; et al. Two decades of pediatric celiac disease in a tertiary referral center: What has changed? Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskimaa, S.; Kivelä, L.; Arvola, T.; Hiltunen, P.; Huhtala, H.; Kaukinen, K.; Kurppa, K. Clinical characteristics and long-term health in celiac disease patients diagnosed in early childhood: Large cohort study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran Cheema, H.A.; Alvi, M.A.; Rehman, M.U.; Ali, M.; Sarwar, H.A. Spectrum of Clinical Presentation of Celiac Disease in Pediatric Population. Cureus 2021, 13, e15582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, L.C.; Brandão, J.M.; Fernandes, M.I.; Campos, A.D. [Clinical presentation of children with celiac disease attended at a Brazilian specialized university service, over two periods of time]. Arq. De Gastroenterol. 2004, 41, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.L.; Withoff, S.; Kolkman, J.J.; Wijmenga, C.; Weersma, R.K.; Visschedijk, M.C. Non-classical clinical presentation at diagnosis by male celiac disease patients of older age. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 83, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.; Sano, K.; Lebwohl, B.; Diamond, B.; Green, P.H. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003, 48, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlbom, I.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Kovács, J.B.; Szalai, Z.; Mäki, M.; Hansson, T. Prediction of clinical and mucosal severity of coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis by quantification of IgA/IgG serum antibodies to tissue transglutaminase. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 50, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhiari, R.; Aljameli, S.M.; Almotairi, D.B.; AlHarbi, G.A.; ALmufadhi, L.; Almeathem, F.K.; Alharbi, A.A.; AlObailan, Y. Clinical Presentation of Pediatric Celiac Disease Patients in the Qassim Region Over Recent Years. Cureus 2022, 14, e21001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, K.; Stack, W.; Hayes, T.; Kenny, E.; Jackson, L. An Investigation Into What Factors Influence Patterns of Clinical Presentation in Adult-Onset Celiac Disease. Cureus 2022, 14, e21924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhaib, S.A.; Mohammed, M.J.; Hamadi, S.S. Assessment of the Predictive Factors Influencing the Diagnosis and Severity of Villous Atrophy in Patients with Celiac Disease and Iron Deficiency Anemia Referred for Diagnostic Endoscopy in Basrah, Iraq. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2022, 36, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtab, W.; Agarwal, H.; Ghosh, T.; Chauhan, A.; Ahmed, A.; Singh, A.; Vij, N.; Singh, N.; Malhotra, A.; Ahuja, V.; et al. Patterns of practice in the diagnosis, dietary counselling and follow-up of patients with celiac disease—A patient-based survey. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riznik, P.; De Leo, L.; Dolinsek, J.; Gyimesi, J.; Klemenak, M.; Koletzko, B.; Koletzko, S.; Koltai, T.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Krencnik, T.; et al. Management of coeliac disease patients after the confirmation of diagnosis in Central Europe. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 34, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, M.; Kocsis, D.; Zágoni, T.; Miheller, P.; Herszényi, L.; Tulassay, Z. Retrospective evaluation of the ten-year experience of a single coeliac centre. Orv. Hetil. 2012, 153, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Cohort of Patients (n = 738) | Patients with Classical Presentation (n = 290) | Patients with Non-Classical Presentation (n = 448) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (median and range, years) (continuous) | 22.8 ± 17.1 | 24.4 ± 18.8 | 21.8 ± 15.9 |

| Age at diagnosis (dichotomous) | |||

| diagnosed in childhood | 362 | 122 | 240 |

| diagnosed in adulthood | 376 | 168 | 208 |

| Sex | |||

| males | 194 | 67 | 127 |

| females | 544 | 223 | 321 |

| tTG IgA at diagnosis | |||

| negative | 39 | 17 | 22 |

| low positive (1.0–9.9 times of the upper normal level) | 159 | 53 | 103 |

| high positive (at least 10 times of the upper normal level) | 407 | 139 | 268 |

| tTG IgG at diagnosis | |||

| negative | 189 | 64 | 125 |

| low positive (1–9.9× titer) | 287 | 102 | 185 |

| high positive (at least 10× titer) | 107 | 33 | 74 |

| EMA (IgA) at diagnosis | |||

| negative | 48 | 21 | 27 |

| weak positive | 16 | 4 | 12 |

| strong positive | 523 | 170 | 353 |

| EMA (IgG) at diagnosis | |||

| negative | 112 | 37 | 75 |

| weak positive | 26 | 10 | 16 |

| strong positive | 274 | 88 | 186 |

| Histology at diagnosis | |||

| Marsh 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Marsh 2 | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Marsh 3a | 61 | 22 | 39 |

| Marsh 3b | 126 | 50 | 76 |

| Marsh 3c | 258 | 103 | 155 |

| Marsh 3 (not classified otherwise) | 14 | 6 | 8 |

| not classified per Marsh/Marsh-Oberhuber criteria | 50 | 23 | 27 |

| non-interpretable or non-specific changes | 17 | 8 | 9 |

| Calendar period | |||

| ≤1998 | 56 | 43 | 13 |

| 1999–2007 | 176 | 78 | 98 |

| 2008–2019 | 506 | 169 | 347 |

| Total Number of Patients | Number of Patients with Classical Presentation | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 392 | 135 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 392 | 135 | |||

| Male | 91 | 25 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| Female | 301 | 110 | 1.34 | 0.79–2.32 | 0.290 |

| Calendar year of diagnosis (years) | 392 | 135 | 0.93 | 0.89–0.98 | 0.006 |

| Histology | 392 | 135 | |||

| Marsh 1+2 | 15 | 5 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| Marsh 3a+b | 151 | 50 | 0.90 | 0.90–3.12 | 0.857 |

| Marsh 3c | 226 | 80 | 1.20 | 0.39–4.11 | 0.758 |

| tTG IgA | 392 | 135 | |||

| negative | 24 | 12 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| low positive | 102 | 40 | 0.63 | 0.25–1.60 | |

| high positive | 266 | 83 | 0.52 | 0.22–1.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szakács, Z.; Farkas, N.; Nagy, E.; Bencs, R.; Vereczkei, Z.; Bajor, J. Clinical Presentation Is Dependent on Age and Calendar Year of Diagnosis in Celiac Disease: A Hungarian Cross-Sectional Study. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13030487

Szakács Z, Farkas N, Nagy E, Bencs R, Vereczkei Z, Bajor J. Clinical Presentation Is Dependent on Age and Calendar Year of Diagnosis in Celiac Disease: A Hungarian Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(3):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13030487

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzakács, Zsolt, Nelli Farkas, Enikő Nagy, Réka Bencs, Zsófia Vereczkei, and Judit Bajor. 2023. "Clinical Presentation Is Dependent on Age and Calendar Year of Diagnosis in Celiac Disease: A Hungarian Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 3: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13030487

APA StyleSzakács, Z., Farkas, N., Nagy, E., Bencs, R., Vereczkei, Z., & Bajor, J. (2023). Clinical Presentation Is Dependent on Age and Calendar Year of Diagnosis in Celiac Disease: A Hungarian Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(3), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13030487