Abstract

Background: In colorectal cancer, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels on postoperative days 3–4 have a strong negative predictive value for an anastomotic leak, with threshold values of ~15 on post-operative day (POD) 3 and ~13 on POD 4. In Crohn’s disease, CRP levels are perceived as unreliable in the postoperative period because of the underlying inflammatory process. The aim of this study was to determine whether postoperative CRP levels can be used to rule out anastomotic leaks in patients with Crohn’s disease and to set CRP threshold values for this population. Methods: This was a retrospective study of a population of Crohn’s disease patients who underwent surgery with bowel anastomoses at a single high-volume center between 1/2012 and 12/2017. The operations were performed by a single colorectal consultant who is an inflammatory bowel disease specialist. Results: Ninety-two operations were performed. A CRP level of 19.56 mg/dL on postoperative day 3 had an area under the curve of 0.865 (sensitivity 88%, specificity 73%) and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98% for an anastomotic leak. Patients with an anastomotic leak showed a trend towards decreased postoperative albumin levels (p = 0.06). Conclusions: Mean CRP levels and CRP threshold values were indeed higher in the study population compared with those in colorectal cancer patients. Threshold values were set at 20.3 mg/dL on POD 3, 19.5 mg/dL on POD 4 and 16.7 mg/dL on POD 5. These values had high NPVs and can be used to rule out anastomotic leaks in patients with Crohn’s disease after surgery with bowel anastomosis.

1. Introduction

Anastomotic leak (AL) is one of the most feared complications of gastrointestinal (GI) surgery. With rates ranging between 2% and 15%, AL is associated with high morbidity and mortality [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. There is no specific method to prevent or to predict an AL. In addition, its diagnosis is not always trivial [8,9,10,11]. Abnormal clinical findings or objective physiological parameters may be absent in the early days after surgery [12,13]; a normal CT scan does not eliminate the possibility of intra-abdominal complications, with false-negative rates of ~20% [14], and output from pelvic drains may be unreliable.

In recent years, C-reactive protein (CRP) has been widely studied as an early predictor of septic complications, including AL, after elective colorectal cancer (CRC) surgery [8,9,10,11]. CRP is an acute-phase reactant protein synthesized in the liver. It is a main component in the inflammatory cascade, with a half-life of 19h, which makes it a very sensitive marker of inflammation [4]. It is commonly used as one of the factors influencing the decision of whether or not a patient is suitable for early discharge after surgery, mainly because of its high negative predictive value (NPV) for ALs [15].

The 10-year risk of surgery in patients with CD is as high as 50% [16]. CRP levels are routinely used as a marker of disease activity in these patients [17,18]. However, patients with CD are usually excluded from studies on postoperative CRP levels because of their altered inflammatory response and common use of anti-inflammatory medications [19].

The objective of this study was to investigate postoperative CRP levels in patients with CD who underwent surgery with bowel anastomoses and to assess its use in the early diagnosis of ALs.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients with CD who underwent elective, semi-elective and urgent abdominal surgery with bowel anastomosis at Meir Medical Center between 1/2012 and 12/2017. The operations were performed by a single colorectal consultant who is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) specialist. Laparoscopic and open bowel resections and “ostomy" reversal surgeries were included in the study. Patients under the age of 18, surgeries with bowel resections without anastomosis and diversion surgeries were excluded.

Patients’ demographics (age, sex and BMI), CD characteristics (anatomic location of the inflamed bowel, past and current medical treatments, past surgeries and extraintestinal manifestations), operative details (indication, laparoscopic, open or converted and site of anastomosis), complications (return to theater and readmission) and length of stay were recorded. All patients received a single dose of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics and pre-/postoperative low-molecular-weight heparin.

Medical records of all patients were reviewed to obtain the following parameters for the postoperative period: white blood cell count (WBC), platelet count (PLT), albumin level and CRP level.

2.1. Definitions

AL was defined as a defect seen in the anastomosis at reoperation, the presence of feculent fluid in a pelvic drain at the bedside or evidence of free air, fluid or extraluminal contrast around the anastomosis on CT. Other septic complications included the following: pneumonia, urinary tract infection, superficial wound sepsis and line sepsis. Noninfectious complications included myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Urgent surgeries were defined as those that took place less than 24 h after nonelective admissions. The indications for these operations were free perforation and intra-abdominal abscess (IAA) not amenable to percutaneous drainage.

Semi-elective surgeries were defined as operations indicated by CD exacerbations that did not require urgent surgical intervention: small (<5 cm) IAAs, IAAs amenable to percutaneous drainage and ongoing inflammation leading to prolonged use of steroids or bowel obstructions. Patients with IAAs were treated preoperatively with intravenous (IV) or oral (PO) antibiotics for a period of at least two weeks prior to surgery and percutaneous drainage when necessary. Patients with inflammation-induced bowel obstructions were treated with antibiotics and/or systemic steroids for a similar period of time. These patients were ideally operated on two weeks after completing the tapering down of systemic steroid treatment.

Elective surgeries were operations indicated by a stenotic bowel obstruction, a planned “ostomy” reversal in a patient in disease remission or bowel resection due to suspected or proven malignancy. These patients were not under systemic steroid treatment at the time of the operation.

All semi-elective and elective patients received preoperative nutritional preparation, either orally or parenterally, for 2–3 weeks.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The statistical software package SPSS 20 (IBM) was used to perform statistical analysis. Normality of data was tested by Shapiro-Wilks. The median was used as a measure of the central tendency for continuous variables. Continuous data were assessed using Student’s t-test, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for nonparametric data. Pearson’s chi-square test was employed for comparison of categorical variables. A p value of <0.05 (two-tailed) was deemed statistically significant.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess the accuracy of CRP in detecting AL on successive postoperative days. This method involves plotting a curve of sensitivity (true positives) against 1-specificity (true negatives). The accuracy of the test is calculated by measuring the AUC, and the curve itself can be used to identify an optimum cutoff value, which will provide the highest sensitivity and specificity combination to best diagnose the outcome measure. Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated at the optimum threshold CRP for each day after surgery.

2.3. Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Meir Medical Center.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was waived by the institutional research committee.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

Patients’ demographic data and preoperative inflammatory markers are shown in Table 1. There were no differences in terms of age, gender, BMI, preoperative inflammatory markers or metabolic state between patients who suffered an AL and those who did not.

Table 1.

Demographics and preoperative inflammatory markers.

3.2. Operative and Preoperative Treatment

Fifty-two procedures were laparoscopic, and forty were open or laparoscopic converted to open. Table 2 describes the different types of operations that were performed.

Table 2.

Types of operations.

There was no difference in leak rates between the laparoscopic and open groups (4 vs. 7, p = 0.15). There were 11 (11.9%) ALs, of which 8 were small bowel to large bowel anastomosis, and 3 were small bowel to small bowel anastomosis (p = 0.79). Antibiotic treatment sufficed as the only intervention in three cases, percutaneous drainage was added in three more cases, and five cases required reoperation. Of the five cases that required reoperation, two had a pin-point leak that was treated with the insertion of a T-drain, one underwent resection of the anastomosis and immediate re-anastomosis, and two required take down of the anastomosis and formation of an ileostomy. The mean postoperative day for the diagnosis of an anastomotic leak was 5.3 ± 3.2. Four patients had an EL that was negative for AL: two on POD 4, one on POD 3 and one on POD 5. These patients had other intra-abdominal septic complications: three had an infected hematoma, and one had a minimal amount of pelvic supportive fluid.

Six operations were urgent (~6%) due to bowel perforation or intra-abdominal abscess not amenable to percutaneous drainage, forty-three operations (47%) were semi-elective (thirty-three due to fistula or intra-abdominal abscesses and ten due to inflammation-induced, recurrent or steroid-dependent bowel obstruction), and forty-three (47%) operations were elective. Only one AL occurred in the urgent operation group, five occurred in the semi-elective group, and five occurred in the elective operation group (p = 0.9).

At the time of the operation, 29 patients were treated with systemic steroids, 23 patients were treated with biologic agents (infliximab, adalimumab or vedolizumab), and five patients were treated with a combination of systemic steroids and biologic agents. Other medical treatments included azathioprine, mercaptopurine and 5-ASA derivatives. None of the patients treated with systemic steroids at the time of the operation suffered an AL.

There were no procedure-related deaths in the study group.

3.3. Analysis of Postoperative CRP Levels

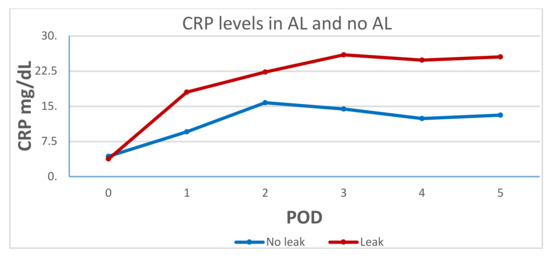

Postoperative CRP levels were higher in the AL group on POD 1 (17.9 ± 11 vs. 9.5 ± 5.4, p = 0.09) and POD 2 (22.2 ± 10.2 vs.15.7 ± 9.7, p = 0.11); however, this difference became significant only on POD 3–5 (see Table 3). Figure 1 demonstrates the difference in CRP levels and trends between the two groups from POD 1 to 5.

Table 3.

Postoperative CRP.

Figure 1.

C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in the anastomotic leak (AL) and the no-AL groups.

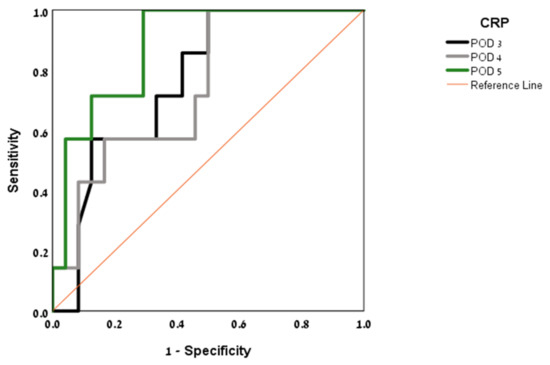

ROC curves were produced for POD 3–5 and analyzed to calculate the area under the curve and optimum CRP threshold (see Figure 2). ROC curve analysis revealed POD 3 to be the most predictive of AL, with an AUC of 0.863 for a CRP threshold value of 19.56 mg/dL (sensitivity 88%, specificity 73%). On POD 4, the AUC was 0.805 for a CRP threshold value of 20 mg/dL (sensitivity 66%, specificity 90%).

Figure 2.

Area under the curve (AUC) by post-operative day (POD).

The threshold value of 19.56 mg/dL on POD 3 was strongly exclusive of an AL, with an NPV of 98%. A threshold value of 12.5 mg/dL on POD 5 had an NPV of 100%. The PPV trended upward from day to day, reaching 100% on POD 5 for a threshold value of 12.5 mg/dL.

WBC and PLT levels on POD 3 did not show a statistically significant difference between the AL and no-AL groups. The albumin level on POD 3 was lower in the AL group with borderline significance (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Other inflammatory markers on POD 3.

4. Discussion

While the measurement of postoperative CRP levels has become a standard practice in CRC surgery in many units, this is not the case for patients with CD undergoing surgery with bowel anastomoses. The main reason for this is the premise that these patients have an altered inflammatory response [20] that affects postoperative CRP levels and their interpretation. In addition, patients with CD have elevated baseline CRP levels [17,18], which may also influence postoperative values. Therefore, postoperative CRP threshold values of CRC patients cannot be applied in CD. This study also showed that although postoperative CRP threshold values are higher in the CD population, they can still be safely used as a tool to rule out anastomotic leaks.

Previous studies have shown that the clinical significance of postoperative CRP measurement is in its NPV for ALs, rather than its PPV [3,7,8,9,10,11,15]. Indeed, this was the case in this study too. The NPV of a CRP level of 19.56 mg/dL on POD 3 was 98%, but the PPV was only 35%. The PPV does increase later in the postoperative period, but by then, other signs of clinical derangement are usually apparent.

A recent meta-analysis by Yeung et al. summarized the results of 23 studies that assessed the use of postoperative CRP levels as a tool to predict ALs in colorectal surgery [21]. In a day-by-day comparison of the AL groups and the no-AL groups, CRP levels in Yeung’s study were lower than in this one, a trend that was consistent from POD 1 to 5 (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean CRP levels and CRP threshold values.

In addition, threshold CRP values were lower than those reported here: 14.8 mg/dL vs. 19.56 mg/dL on POD 3, 12.3 mg/dL vs. 20.0 mg/dL on POD 4 and 11.5 mg/dL vs. 12.5 mg/dL on POD 5. This finding of relatively elevated postoperative CRP levels in patients with CD correlates with previous reports by Carvello [19] and de Buck [20]. A summary of the differences in CRP values between patients with CD and other colorectal surgery patients is displayed in Table 5.

Low albumin levels in the postoperative period have recently been shown to have a correlation with postoperative complications [22,23]. In this study, postoperative albumin levels showed only a trend toward lower values in patients with AL (3.03 ± 0.5 vs. 2.71 ± 0.4, p = 0.06).

This dedicated study is one of the first to address the use of postoperative CRP levels as a tool to rule out ALs in the CD population. Its clinical contribution is in showing that this practice can be implemented not only in the elective surgery setting but also in a heterogeneous group of CD patients that includes emergent cases. This is significant because, in CD, more often than not, patients reach surgical intervention during or soon after disease exacerbation. The limitation of this study is its small cohort size and retrospective nature, which subjects it to selection bias and record-keeping issues.

In conclusion, mean postoperative CRP levels and threshold CRP values are higher in patients with CD undergoing bowel anastomoses compared with patients undergoing operations for CRC. Nonetheless, postoperative CRP levels can be used to rule out ALs in patients with CD. We suggest a threshold of 20.3 mg/dL on POD 3, 19.5 mg/dL on POD 4 and 16.7 mg/dL on POD 5. More dedicated studies on the CD population are required to validate these results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.S.; data curation, A.G.; formal analysis, Y.R.; validation, B.R.; writing—original draft, M.S. and S.A.; writing—review and editing M.S. and I.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Meir medical Center (protocol code MMC-0119-17, June 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and with the approval of the Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study are available upon request under instructions of the Institutional Review Board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| AL | anastomotic leak |

| EL | exploratory laparoscopy |

| CT | computed tomography |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| BMI | body mass index |

| WBC | white blood cell count |

| PLT | platelet count |

| IV | intravenous |

| PO | per oral |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| POD | postoperative day |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

References

- Alves, A.; Panis, Y.; Mathieu, P.; Mantion, G.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Slim, K. Postoperative mortality and morbidity in French patients undergoing colorectal surgery: Results of a prospective multicenter study. Arch. Surg. 2005, 140, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongen, A.C.H.M.; Bosmans, J.W.A.M.; Kartal, S.; Lubbers, T.; Sosef, M.; Slooter, G.D.; Stoot, J.H.; Van Schooten, F.-J.; Bouvy, N.D.; Derikx, J.P.M. Predictive Factors for Anastomotic Leakage After Colorectal Surgery: Study Protocol for a Prospective Observational Study (REVEAL Study). JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Deballon, P.; Radais, F.; Facy, O.; D’Athis, P.; Masson, D.; Charles, P.E.; Cheynel, N.; Favre, J.-P.; Rat, P. C-reactive protein is an early predictor of septic complications after elective colorectal surgery. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, T.; Müller, S.A.; Ulrich, A.; Kischlat, A.; Hinz, U.; Kienle, P.; Büchler, M.W.; Schmidt, J.; Schmied, B.M. C-reactive protein as early predictor for infectious postoperative complications in rectal surgery. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2007, 22, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, J.C.; Wright, S.; Burch, J.; Kennedy, R.H.; Jenkins, J.T. Early prediction of adverse events in enhanced recovery based upon the host systemic inflammatory response. Color. Dis. 2013, 15, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warschkow, R.; Tarantino, I.; Torzewski, M.; Näf, F.; Lange, J.; Steffen, T. Diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein and white blood cell counts in the early detection of inflammatory complications after open resection of colorectal cancer: A retrospective study of 1,187 patients. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2011, 26, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, J.J.; Ramanathan, M.L.; Crosbie, R.A.; Anderson, J.H.; McKee, R.F.; Horgan, P.G.; McMillan, D. C-reactive protein as a predictor of postoperative infective complications after curative resection in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 4168–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; De Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phitayakorn, R.; Delaney, C.P.; Reynolds, H.L.; Champagne, B.J.; Heriot, A.G.; Neary, P.; Senagore, A.J.; International Anastomotic Leak Study Group. Standardized algorithms for management of anastomotic leaks and related abdominal and pelvic abscesses after colorectal surgery. World J. Surg. 2008, 32, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, J.; Bokey, E.L.; Chapuis, P.H.; Sinclair, G.; Dent, O.F. Anastomotic leakage after resection of colorectal cancer generates prodigious use of hospital resources. Color. Dis. 2009, 11, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarthur, D.C.; Nixon, S.J.; Aitken, R.J. Avoidable deaths still occur after large bowel surgery. Scottish audit of surgical mortality, royal college of surgeons of Edinburgh. Br. J. Surg. 1998, 85, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, N.; Manchester, T.L.; Osler, T.; Burns, B.; Cataldo, P.A. Anastomotic leaks after intestinal anastomosis: It’s later than you think. Ann. Surg. 2007, 245, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amamoto, T.; Allan, R.N.; Keighley, M. Risk factors for intra-abdominal sepsis after surgery in Crohn’s disease. Dis. Colon Rectum 2000, 43, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, S.; Fournel, I.; Orry, D.; Facy, O.; Cheynel, N.; Rat, P.; Ortega-Deballon, P. Should CT scan be performed when CRP is elevated after colorectal surgery? Results from the inflammatory markers after colorectal surgery study. J. Visc. Surg. 2017, 154, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Zeng, I.S.; Srinivasa, S.; Lemanu, D.P.; Connolly, A.B.; Hill, A.G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of use of serum C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2014, 101, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, W.; Stafford, C.; Francone, T.D.; Read, T.E.; Marcello, P.W.; Roberts, P.L.; Ricciardi, R. What Is the Risk of Anastomotic Leak After Repeat Intestinal Resection in Patients With Crohn’s Disease? Dis. Colon Rectum 2017, 60, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boirivant, M.; Leoni, M.; Tariciotti, D.; Fais, S.; Squarcia, O.; Pallone, F. The clinical significance of serum C reactive protein levels in Crohn’s disease. Results of a prospective longitudinal study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1988, 10, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iaculli, E.; Agostini, M.; Biancone, L.; Fiorani, C.; Di Vizia, A.; Montagnese, F.; Sibio, S.; Manzelli, A.; Tesauro, M.; Rufini, A.; et al. C-reactive protein levels in the perioperative period as a predictive marker of endoscopic recurrence after ileo-colonic resection for Crohn’s disease. Cell Death Discov. 2016, 2, 16032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carvello, M.; Di Candido, F.; Greco, M.; Foppa, C.; Maroli, A.; Fiorino, G.; Cecconi, M.; Danese, S.; Spinelli, A. The trend of C-Reactive protein allows a safe early discharge after surgery for Crohn’s disease. Updat. Surg. 2020, 72, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstraeten, A.D.B.V.; Van Hoef, S.; Vermeire, S.; Ferrante, M.; Fieuws, S.; Wolthuis, A.M.; Van Assche, G.; D’Hoore, A. Postoperative Inflammatory Response in Crohn’s Patients: A Comparative Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, D.E.; Peterknecht, E.; Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Torrance, A.W. C-reactive protein can predict anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuge, L.; Zheng, D.; Mao, H.; Xiang, J.; Chen, H. Impact of post-operative serum albumin level on anastomotic leakage after transthoracic oesophagectomy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, E7–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasson, M.; Granero-Castro, P.; Rodríguez, J.L.R.; Flor-Lorente, B.; Braithwaite, M.; Martínez, E.M.; Pérez, J.A.Á.; Cazador, A.C.; Espí, A.; ANACO Study Group; et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leak and postoperative morbidity and mortality after elective right colectomy for cancer: Results from a prospective, multicentric study of 1102 patients. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2016, 31, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).