Analysis of Dento-Facial Parameters in the Young Population Using Digital Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethics Approval, and Sample Size Considerations

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Image Processing

- Position A: the participant’s position,

- Position B: the photographer’s position at 1 m from the participant (for facial photographs),

- Position C: the photographer’s position at 40 cm from the participant (for dental photographs) (Figure 1).

2.4. Measurement Reliability and Validity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Teeth Parameters

3.2. Facial Parameters

3.3. Soft Tissue Parameters

3.4. Interincisal Angles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

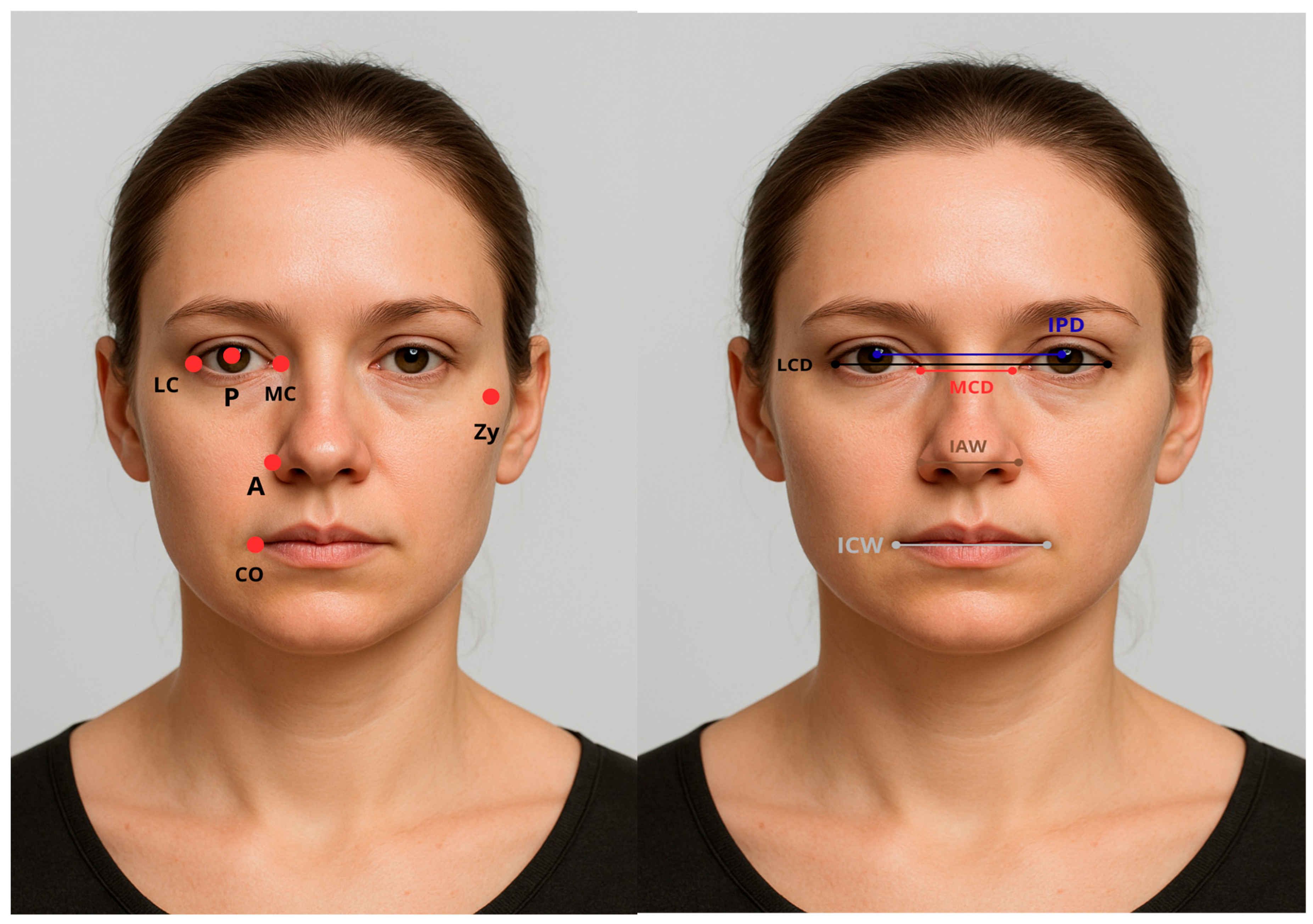

| P | Pupil |

| LC | Lateral eye canthus |

| MC | Medial eye canthus |

| Zy | Zygion |

| LCD | Lateral canthus of the eye distance |

| MCD | Medial canthus of the eye distance |

| IPD | Interpupillary distance |

| IAW | Interalar width |

| ICW | Intercommissural width |

| BZD | Bizygomatic distance |

| CIW | Width of central incisors |

| CLIW | Width of central and lateral incisors |

| ICD | Intercanine distance |

| IPA | Interpapillary Angle |

| IIA | Interincisal Angle |

| HIP | Height of interdental papilla |

References

- Pham, T.A.V.; Nguyen, P.A. Morphological Features of Smile Attractiveness and Related Factors Influence Perception and Gingival Aesthetic Parameters. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayahpour, B.; Eslami, S.; Usherenko, R.; Jamilian, A.; Gonzalez Balut, M.; Plein, N.; Grassia, V.; Nucci, L. Impact of Dental Midline Shift on the Perception of Facial Attractiveness in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 13, 3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.C.; Jones, B.C.; DeBruine, L.M. Facial attractiveness: Evolutionary based research. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1638–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, G.; Simmons, L.W.; Peters, M. Facial Attractiveness: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2024, 45, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mamidi, D.; Vasa, A.A.K.; Sahana, S.; Done, V.; Pavanilakshmi, S. The Assessment of Golden Proportion in Primary Dentition. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2020, 11, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinelli, F.; Piva, F.; Bertini, F.; Scaminaci Russo, D.; Giachetti, L. Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimensions and Relative Width Proportions: A Narrative Literature Review. Dent. J. 2023, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londono, J.; Ghasemi, S.; Lawand, G.; Dashti, M. Evaluation of the Golden Proportion in the Natural Dentition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiallouridou, I.; Sarafidou, K.; Theocharidou, A.; Menexes, G.; Anastassiadou, V. Anthropometric vs. Dental Variables of the Ageing Face: A Clinical Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffaf, M.B.; Şakar, O. Evaluation of Various Anthropometric Measurements for the Determination of the Occlusal Vertical Dimension. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadain, S.M.; Soomro, T.A.S.; Abro, F.A.; Abbasi, M.H.; Arzoo, K. Facial Metrics as Predictors of Occlusal Vertical Dimension: An Anthropometric Analysis. J. Univ. Med. Dent. Coll. 2025, 16, 965–969. [Google Scholar]

- Stăncioiu, A.-A.; Motofelea, A.C.; Popa, A.; Nagib, R.; Lung, R.-B.; Szuhanek, C. Advanced 3D Facial Scanning in Orthodontics: A Correlative Analysis of Craniofacial Anthropometric Parameters. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, F.L.; Yang, H.X.; Li, L.M. Correlation between Different Points on the Face and the Width of Maxillary Anterior Teeth. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, S.K.; Zhang, H.D.; Chang, T.; Dhungana, M.; Acharya, L.; Chen, L.L.; Ding, Y.M. Maxillary Anterior Teeth Dimensions and Proportions in a Central Mainland Chinese Population. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 17, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siwan, D.; Krishan, K.; Sharma, V.; Garg, A.K. A Novel Approach to Developing Machine Learning-Based Models for the Prediction of Facial Dimensions from Dental Parameters. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srimaneekarn, N.; Arayapisit, T.; Pooktuantong, O.; Cheng, H.R.; Soonsawad, P. Determining of Canine Position by Multiple Facial Landmarks to Achieve Natural Esthetics in Complete Denture Treatment. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolte, R.A.; Kolte, A.P.; Deshpande, N.M.; Tuli, P.S. Evaluation and Correlation of Facial and Anterior Teeth Proportions in Periodontally Healthy Patients with Different Facial Types: A Gender-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2025, 29, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, S.L.; Manandhar, P.; Thapa, N.; Pradhan, D.; Parajuli, U. Evaluation of the relationship between the interpupillary distance and mesiodistal width of maxillary anterior teeth in Nepalese population. J. Gandaki Med. Coll.-Nepal. 2023, 16, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrego, V.S.-C.; Carruitero, M. Relationship between the inner intercanthal distance and the mesiodistal dimension of maxillary anterior teeth in a Peruvian population with facial harmony. J. Oral Res. 2019, 8, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Alshamri, H.A.; Al Moaleem, M.M.; Al-Huthaifi, B.H.; Al-Labani, M.A.; Naseeb, W.R.B.; Daghriri, S.M.; Suhail, I.M.; Hamzi, W.H.; Abu Illah, M.J.; Thubab, A.Y.; et al. Correlation between Maxillary Anterior Teeth and Common Facial Measurements. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2023, 15, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

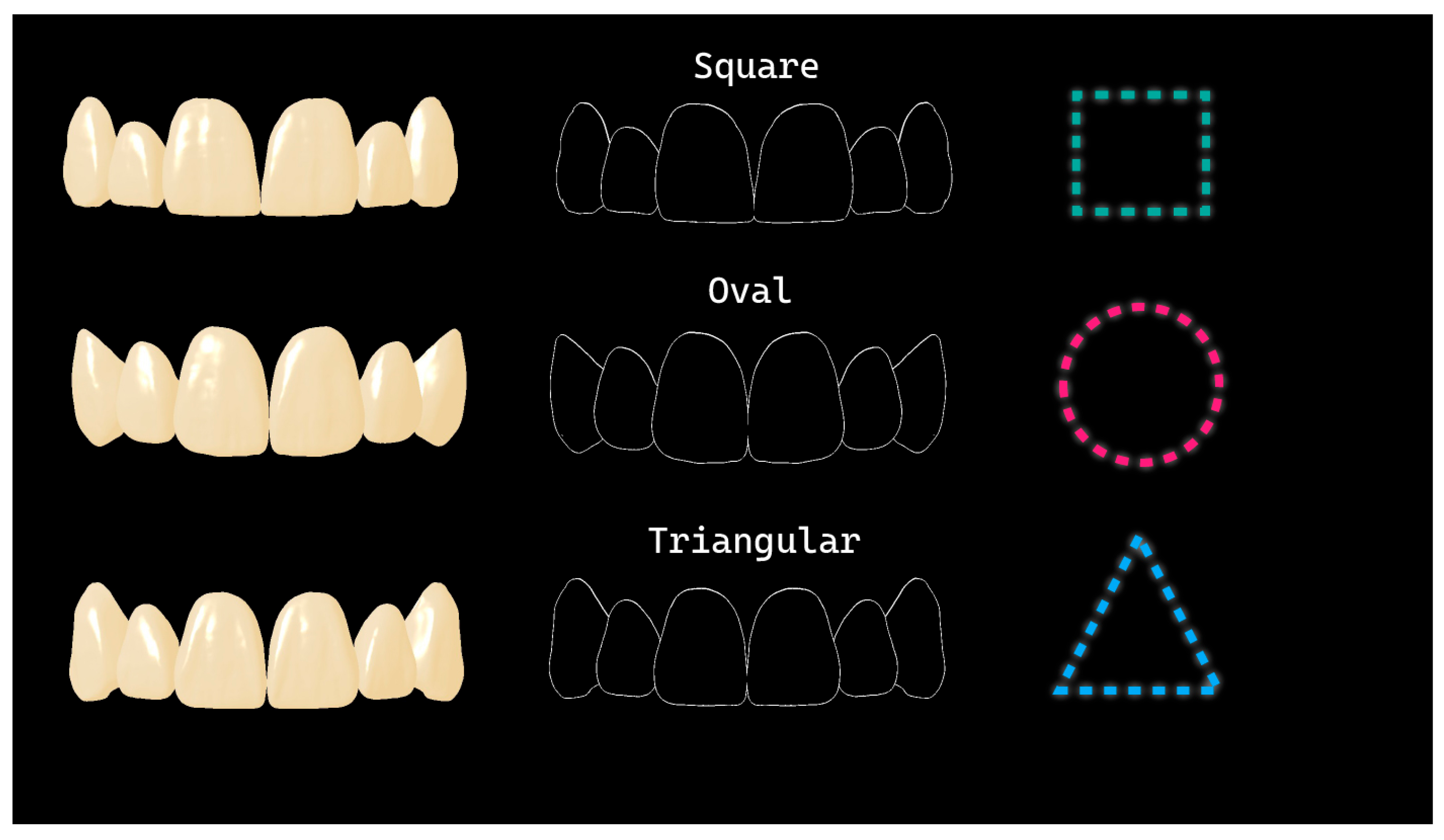

- Williams, J.L. A New Classification of Natural and Artificial Teeth; Dentists Supply Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Kostić, M.; Đorđević, N.S.; Gligorijević, N.; Jovanović, M.; Đerlek, E.; Todorović, K.; Jovanović, G.; Todić, J.; Igić, M. Correlation Theory of the Maxillary Central Incisor, Face and Dental Arch Shape in the Serbian Population. Medicina 2023, 59, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, M.K.; Singh, R.K.; Suwal, P.; Parajuli, P.K.; Shrestha, P.; Baral, D. A Comparative Study to Find Out the Relationship between the Inner Inter-Canthal Distance, Interpupillary Distance, Inter-Commissural Width, Inter-Alar Width, and the Width of Maxillary Anterior Teeth in Aryans and Mongoloids. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2016, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Kannan, A.; Kailasam, V. Morphological Dimensions of the Permanent Dentition in Various Malocclusions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Varo, A.; Arroyo-Cruz, G.; Martínez-de-Fuentes, R.; Jiménez-Castellanos, E. Biometric Analysis of the Clinical Crown and the Width/Length Ratio in the Maxillary Anterior Region. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 113, 565–570.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwanati, M.; Karia, A.; Yuwanati, M. Canine Tooth Dimorphism: An Adjunct for Establishing Sex Identity. J. Forensic Dent. Sci. 2012, 4, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almugla, Y.M.; Madiraju, G.S.; Mohan, R.; Abraham, S. Gender Dimorphism in Maxillary Permanent Canine Odontometrics Based on a Three-Dimensional Digital Method and Discriminant Function Analysis in the Saudi Population. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, K.W.; Honrath, N.; Weykamp, M.; Grönebaum, P.; Nicklisch, N.; Vach, W. Correlation of Tooth Sizes and Jaw Dimensions with Biological Sex and Stature in a Contemporary Central European Population. Biology 2024, 13, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Abbasi, M.S.; Khan, D.A.; Khalid, S.; Jawed, W.; Mahmood, M. Determination of the Combined Width of Maxillary Anterior Teeth Using Innercanthal Distance with Respect to Age, Gender and Ethnicity. Pak. Armed Forces Med. J. 2021, 71, S164–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attokaran, G.; Shenoy, K. Correlation between Interalar Distance and Mesiodistal Width of Maxillary Anterior Teeth in Thrissur, Kerala, Indian Population. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2018, 8, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Y.; Sahbaz, I.; Kar, T.; Kagan, G.; Taner, M.T.; Armagan, I.; Cakici, B. Evaluation of Interpupillary Distance in the Turkish Population. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2015, 9, 1413–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervarič, T.; Fekonja, A. Relationship between Facial Length/Width and Crown Length/Width of the Permanent Maxillary Central Incisors. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Arora, A.; Valiathan, A. Age Changes of Jaws and Soft Tissue Profile. Sci. World. J. 2014, 2014, 301501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sülün, T.; Ergin, U.; Tuncer, N. The nose shape as a predictor of maxillary central and lateral incisor width. Quintessence Int. 2005, 36, 603–660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibrahimagic, L.; Celebic, A.; Jerolimov, V. Correlation between the size of maxillary frontal teeth, the width between Alae Nasi and the width between corners of the lips. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2001, 35, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Eltahir, M.A.; Alnasser, I.; Aljaber, S. Interpupillary and Intercanthal Distance Values among Females in the Al-Qassim Region, KSA: A Cross-Sectional Study. Saudi J. Oral Sci. 2025, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesharaki, H.; Rezaei, L.; Farrahi, F.; Banihashem, T.; Jahanbakhshi, A. Normal Interpupillary Distance Values in an Iranian Population. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2012, 7, 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, R.; Rahman, M.; Majumder, B.; Rumon, K.; Biswas, U.; Hossain, M. Relationship between the Interpupillary Distance and the Width of Maxillary Anterior Teeth of Different Face Forms among Bangladeshi Adult Population. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 10, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarna, K.; Sonigra, K.J.; Ngeow, W.C. A Cross-Sectional Study to Determine and Compare the Craniofacial Anthropometric Norms in a Selected Kenyan and Chinese Population. Plast. Surg. 2023, 31, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.R.P.; Machado, C.E.P.; Gallidabino, M.D.; de Arruda, G.H.M.; da Silva, R.H.A.; de Vidal, F.B.; Melani, R.F.H. Comparative Assessment of a Novel Photo-Anthropometric Landmark-Positioning Approach for the Analysis of Facial Structures on Two-Dimensional Images. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengou, X.; Frank, K.; Kaye, K.; Brébant, V.; Möllhoff, N.; Cotofana, S.; Alfertshofer, M. Facial Anthropometric Measurements and Principles—Overview and Implications for Aesthetic Treatments. Facial Plast. Surg. 2024, 40, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alresheedi, B.A. Assessment of the Relationship between Craniofacial Measurements and Maxillary Central Incisor Width Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, S3456–S3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.S.; Syed Mohamed, A.M.F.; Marizan Nor, M.; Rosli, T.I. Gender and Age Effects on Dental and Palatal Arch Dimensions among Full Siblings. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 65, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolte, R.A.; Kolte, A.P.; Ikhar, A.S. Gender-Based Evaluation of Positional Variations of Gingival Papilla and Its Proportions: A Clinicoradiographic Study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2022, 26, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Lopes, P.C.; Rio, R. The Interference of Age and Gender on Smile Characterization Analyzed on Six Parameters: A Clinical-Photographic Pilot Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović Đuričić, K.; Kostić, L.J.; Martinović, Ž. Gingival and dental parameters in evaluation of esthetic characteristics of fixed restoratons. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2005, 133, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, M.; Awad, R.; Mohammed, A.; Abdallah, H.; Elhoumed, M.; Al-Waraf, L.; Qu, W.; Alhashimi, N.; Chen, X.; Wang, S. Effect of Ethnic, Professional, Gender, and Social Background on the Perception of Upper Dental Midline Deviations in Smile Esthetics by Chinese and Black Raters. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saleh, S.; Abu-Raisi, S.; Almajed, N.; Bukhary, F. Esthetic self-perception of smiles among a group of dental students. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2018, 13, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Mannaa, A.I. Knowledge and Attitude Toward Esthetic Dentistry and Smile Perception. Cureus 2023, 15, e46043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsurayyi, M.; Almutairi, W.; Binsaeed, A.; Aldhuwayhi, S.; Shaikh, S.; Mustafa, M. A Cross-Sectional Online Survey on Knowledge, Awareness, and Perceptions of Hollywood Smile Among the Saudi Arabia Population. Open. Dent. J. 2022, 16, e187421062111261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soft Tissue Points | Description |

|---|---|

| Pupil (P) | The center of the pupil |

| Lateral eye canthus (LC) | The outer point of the eye |

| Medial eye canthus (MC) | The inner point of the eye |

| Zygion (Zy) | The most lateral soft tissue points of the zygomatic arch |

| Alar (A) | The outer point of the alar |

| Lip commissure (CO) | The outer point of the lip |

| Facial Landmarks | Description |

|---|---|

| Lateral canthus of the eye distance (LCD) | Right LC–Left LC |

| Medial canthus of the eye distance (MCD) | Right MC–Left MC |

| Interpupillary distance (IPD) | Right P–Left P |

| Interalar width (IAW) | Right A–Left A |

| Intercommissural width (ICW) | Right CO–Left CO |

| Bizygomatic distance (BZD) | Right Zy–Left Zy |

| Dental Landmarks | Description |

|---|---|

| Tooth Width | Distance between the mesial and distal contact points of a given tooth |

| Interpapillary Angle (IPA) | The angle formed by the papilla of two adjacent teeth, with its apex facing incisally and open towards gingivally |

| Interincisal Angle (IIA) | The angle formed by the incisal edges of two adjacent teeth, with its apex facing gingivally and open towards incisally |

| Height of interdental papilla (HIP) | Distance from the tip of the papilla to the tangent passing through the zenith of the given tooth |

| Characteristics | Participants (n = 82) | Male (n = 20) | Female (n = 62) | p Value (Between Gender) | Mean Difference | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age | 24.88 ± 2.891 | 25.05 ± 3.120 | 24.50 ± 2.733 | 0.056 | 1.550 | −0.044 | 3.144 |

| Right central incisor width | 8.980 ± 0.694 | 9.005 ± 0.666 | 8.973 ± 0.708 | 0.853 | 0.0324 | −0.3216 | 0.3864 |

| Right lateral incisor width | 6.137 ± 0.672 | 6.220 ± 0.583 | 6.110 ± 0.701 | 0.489 | 0.1103 | −0.2095 | 0.4301 |

| Right canine width | 6.763 ± 0.578 | 6.910 ± 0.487 | 6.569 ± 0.454 | 0.010 * | 0.3406 | 0.0889 | 0.5924 |

| Left central incisor width | 9.015 ± 0.699 | 9.115 ± 0.584 | 8.982 ± 0.734 | 0.413 | 0.1327 | −0.1916 | 0.4571 |

| Left lateral incisor width | 6.067 ± 0.665 | 6.165 ± 0.612 | 6.035 ± 0.683 | 0.430 | 0.1295 | −0.2121 | 0.4711 |

| Left canine width | 6.851 ± 0.554 | 6.925 ± 0.498 | 6.681 ± 0.454 | 0.061 | 0.2444 | 0.0064 | 0.4823 |

| CIW | 17.995 ± 1.355 | 18.120 ± 1.189 | 17.955 ± 1.411 | 0.610 | 0.1652 | −0.4842 | 0.8145 |

| CLIW | 30.198 ± 2.230 | 30.505 ± 1.857 | 30.1 ± 2.341 | 0.429 | 0.4082 | −0.6239 | 1.4403 |

| ICD | 43.591 ± 2.345 | 44.34 ± 2.046 | 43.35 ± 2.398 | 0.080 | 0.990 | −0.1235 | 2.1035 |

| Facial Variable | Participants (n = 82) | Male (n = 20) | Female (n = 62) | p Value (Between Gender) | Mean Difference | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| BZD | 142.91 ± 24.067 | 152.29 ± 6.579 | 144.547 ± 7.511 | <0.001 * | 7.9545 | 4.4024 | 11.5067 |

| IAW | 36.54 ± 3.23 | 39.22 ± 3.502 | 35.676 ± 2.631 | <0.001 * | 3.5442 | 1.7949 | 5.2935 |

| ICW | 51.822 ± 3.95 | 53.755 ± 5.208 | 51.198 ± 3.264 | 0.05 | 2.5566 | 0.0051 | 5.1081 |

| LCD | 89.763 ± 5.189 | 89.880 ± 6.043 | 89.726 ± 4.937 | 0.918 | 0.1542 | −2.8990 | 3.2074 |

| MCD | 32.106 ± 3.232 | 31.985 ± 3.141 | 32.145 ± 3.285 | 0.846 | −0.1602 | −1.8217 | 1.5014 |

| IPD | 64.074 ± 5.643 | 65.225 ± 4.418 | 63.703 ± 5.969 | 0.228 | 1.5218 | −0.9891 | 4.0327 |

| Variable (Whole Participants n = 82) | Right Central Incisor Width | Left Central Incisor Width | Right Lateral Incisor Width | Left Lateral Incisor Width | Right Canine Width | Left Canine Width | CIW | CLIW | ICD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BZD | r = 0.432 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.464 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.390 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.295 p < 0.001 * | r = −0.043 p = 0.699 | r = −0.149 p = 0.180 | r = 0.461 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.486 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.423 p < 0.001 * |

| 95% Confidence interval (lower-upper) | |||||||||

| 0.237–0.593 | 0.275–0.619 | 0.189–0.560 | 0.083–0.481 | −0.285–0.176 | −0.355–0.07 | 0.271–0.616 | 0.301–0.636 | 0.227–0.586 | |

| IAW | r = 0.321 p = 0.003 * | r = 0.323 p = 0.003 * | r = 0.354 p = 0.001 * | r = 0.338 p = 0.002 * | r = −0.036 p = 0.749 | r = −0.137 p = 0.220 | r = 0.331 p = 0.002 * | r = 0.409 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.354 p = 0.001 * |

| 95% Confidence interval (lower-upper) | |||||||||

| 0.112–0.503 | 0.114–0.505 | 0.148–0.530 | 0.131–0.517 | −0.251–0.182 | −0.344–0.082 | 0.123–0.511 | 0.211–0.575 | 0.148–0.53 | |

| ICW | r = 0.421 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.412 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.385 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.328 p = 0.003 * | r = −0.142 p = 0.204 | r = −0.236 p = 0.033 * | r = 0.428 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.474 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.374 p = 0.001 * |

| 95% Confidence interval (lower-upper) | |||||||||

| 0.224–0.585 | 0.214–0.577 | 0.183–0.556 | 0.119–0.509 | −0.348–0.077 | −0.431–−0.02 | 0.233–0.590 | 0.286–0.627 | 0.171–0.547 | |

| LCD | r = 0.423 p < 0.001 | r = 0.464 p < 0.001 | r = 0.410 p < 0.001 | r = 0.299 p = 0.006 | r = −0.159 p = 0.153 | r = −0.190 p = 0.087 | r = 0.457 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.490 p < 0.001 * | r = 0.546 p < 0.001 * |

| 95% Confidence interval (lower-upper) | |||||||||

| 0.227–0.586 | 0.275–0.619 | 0.212–0.576 | 0.088–0.485 | −0.363–0.06 | −0.391–0.028 | 0.266–0.613 | 0.305–0.639 | 0.373–0.682 | |

| MCD | r = 0.218 p = 0.049 | r = 0.263 p = 0.017 | r = 0.366 p = 0.001 | r = 0.249 p = 0.024 | r = −0.123 p = 0.271 | r = −0.148 p = 0.184 | r = 0.247 p = 0.025 * | r = 0.335 p = 0.002 * | r = 0.397 p < 0.001 * |

| 95% Confidence interval (lower-upper) | |||||||||

| 0.001–0.415 | 0.049–0.454 | 0.162–0.540 | 0.034–0.442 | −0.331–0.097 | −0.354–0.071 | 0.032–0.440 | 0.127–0.515 | 0.197–0.565 | |

| IPD | r = 0.265 p = 0.016 * | r = 0.292 p = 0.008 * | r = 0.290 p = 0.008 * | r = 0.145 p = 0.193 | r = −0.119 p = 0.288 | r = −0.124 p = 0.266 | r = 0.287 p = 0.009 * | r = 0.305 p = 0.005 * | r = 0.265 p = 0.016 * |

| 95% Confidence interval (lower-upper) | |||||||||

| 0.051–0.456 | 0.08–0.479 | 0.078–0.477 | −0.074–0.351 | −0.328–0.101 | −0.332–0.096 | 0.075–0.474 | 0.094–0.490 | 0.051–0.456 | |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p Value | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| CIW | (Constant) | 0.712 | 3.348 | 0.213 | 0.832 | −5.960 | 7.383 | |

| BZD | 0.067 | 0.033 | 0.398 | 2.038 | 0.045 * | 0.002 | 0.133 | |

| IAW | 0.034 | 0.076 | 0.080 | 0.442 | 0.660 | −0.118 | 0.186 | |

| ICW | 0.026 | 0.059 | 0.077 | 0.448 | 0.656 | −0.091 | 0.143 | |

| LCD | 0.053 | 0.055 | 0.201 | 0.948 | 0.346 | −0.058 | 0.163 | |

| MCD | −0.112 | 0.064 | −0.267 | −1.736 | 0.087 | −0.240 | 0.017 | |

| IPD | 0.040 | 0.035 | 0.168 | 1.163 | 0.249 | −0.029 | 0.110 | |

| Gender | 0.644 | 0.432 | 0.205 | 1.492 | 0.140 | −0.216 | 1.505 | |

| CLIW | (Constant) | 2.449 | 5.432 | 0.451 | 0.653 | −8.375 | 13.273 | |

| BZD | 0.082 | 0.054 | 0.296 | 1.540 | 0.128 | −0.024 | 0.189 | |

| IAW | 0.116 | 0.124 | 0.168 | 0.938 | 0.351 | −0.131 | 0.363 | |

| ICW | 0.054 | 0.095 | 0.096 | 0.569 | 0.571 | −0.136 | 0.244 | |

| LCD | 0.069 | 0.090 | 0.161 | 0.767 | 0.445 | −0.110 | 0.248 | |

| MCD | −0.093 | 0.105 | −0.134 | −0.885 | 0.379 | −0.301 | 0.116 | |

| IPD | 0.059 | 0.056 | 0.150 | 1.054 | 0.295 | −0.053 | 0.172 | |

| Gender | 0.914 | 0.701 | 0.177 | 1.304 | 0.196 | −0.483 | 2.310 | |

| ICD | (Constant) | 23.152 | 6.161 | 3.758 | 0.000 | 10.876 | 35.428 | |

| BZD | 0.058 | 0.061 | 0.197 | 0.948 | 0.346 | −0.063 | 0.179 | |

| IAW | 0.068 | 0.140 | 0.094 | 0.487 | 0.628 | −0.212 | 0.348 | |

| ICW | 0.023 | 0.108 | 0.039 | 0.213 | 0.832 | −0.192 | 0.238 | |

| LCD | 0.101 | 0.102 | 0.224 | 0.991 | 0.325 | −0.102 | 0.305 | |

| MCD | −0.071 | 0.119 | −0.098 | −0.601 | 0.550 | −0.308 | 0.165 | |

| IPD | 0.028 | 0.064 | 0.068 | 0.444 | 0.658 | −0.099 | 0.156 | |

| Gender | −0.161 | 0.795 | −0.030 | −0.202 | 0.840 | −1.745 | 1.423 | |

| Characteristics | Participants (n = 82) | Male (n = 20) | Female (n = 62) | p Value (Between Gender) | Mean Difference | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| HIP 1 (between central incisors) | 6.950 ± 1.903 | 7.770 ± 1.579 | 6.685 ± 1.934 | 0.016 * | 1.0845 | 0.2143 | 1.9547 |

| HIP 2 (between right central and lateral incisor) | 5.927 ± 1.475 | 6.420 ± 1.347 | 5.768 ± 1.489 | 0.075 | 0.6523 | −0.0696 | 1.3742 |

| HIP 3 (between right lateral incisor and canine) | 6.635 ± 1.804 | 7.095 ± 2.062 | 6.487 ± 1.705 | 0.243 | 0.6079 | −0.4361 | 1.6519 |

| HIP 4 (between left central and lateral incisor) | 6.240 ± 1.357 | 6.585 ± 1.512 | 6.129 ± 1.297 | 0.235 | 0.4560 | −0.3139 | 1.2259 |

| HIP 5 (between left lateral incisor and canine) | 6.657 ± 1.754 | 6.980 ± 2.044 | 6.553 ± 1.655 | 0.404 | 0.4268 | −0.6047 | 1.4582 |

| IPA 1 (between central incisors) | 62.144 ± 16.136 | 56.950 ± 11.424 | 63.819 ± 17.128 | 0.046 * | −6.8694 | −13.6134 | −0.1253 |

| IPA 2 (between right central and lateral incisor) | 56.888 ± 12.250 | 55.040 ± 11.557 | 57.484 ± 12.498 | 0.426 | −2.4439 | −8.7289 | 3.8412 |

| IPA 3 (between right lateral incisor and canine) | 52.324 ± 11.194 | 50.690 ± 10.400 | 52.852 ± 11.467 | 0.436 | −2.1616 | −7.7314 | 3.4081 |

| IPA 4 (between left central and lateral incisor) | 54.633 ± 10.936 | 51.035 ± 10.274 | 55.794 ± 10.969 | 0.085 | −4.7585 | −10.2184 | 0.7013 |

| IPA 5 (between left lateral incisor and canine) | 51.344 ± 9.696 | 52.710 ± 8.850 | 50.903 ± 9.982 | 0.447 | 1.8068 | −2.9603 | 6.5738 |

| Variable | Oval Shape (n = 18) | Triangular Shape (n = 23) | Square Shape (n = 41) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA between central incisors | 65.878 ± 20.345 | 52.357 ± 11.439 | 65.995 ± 14.240 | Oval vs. triangular p = 0.054 |

| Oval vs. square p = 1.000 | ||||

| Triangular vs. square p ˂ 0.001 * | ||||

| HIP between central incisors | 6.594 ± 1.962 | 6.337 ± 1.502 | 8.322 ± 1.866 | Oval vs. triangular p = 0.021 * |

| Oval vs. square p = 0.947 | ||||

| Triangular vs. square p ˂ 0.001 * |

| Variable (Angle Between Incisal Edges) | Participants (n = 82) | Male (n = 20) | Female (n = 62) | p Value (Between Gender) | Mean Difference | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| IIA 1 (Central incisors) | 50.341 ± 21.137 | 52.430 ± 24.543 | 49.668 ± 20.094 | 0.652 | 2.7623 | −9.6414 | 15.1659 |

| IIA 2 (Right central and lateral incisor) | 61.157 ± 21.863 | 58.245 ± 19.103 | 62.097 ± 22.746 | 0.460 | −3.8518 | −14.2922 | 6.5887 |

| IIA 3 (Right lateral incisor and canine) | 75.911 ± 19.189 | 75.315 ± 20.230 | 76.103 ± 19.009 | 0.879 | −0.7882 | −11.2515 | 9.6750 |

| IIA 4 (Left central and lateral incisor) | 58.512 ± 18.258 | 57.365 ± 18.259 | 58.882 ± 18.391 | 0.749 | −1.5173 | −11.0939 | 8.0594 |

| IIA 5 (Left lateral incisor and canine) | 68.743 ± 19.306 | 70.930 ± 20.031 | 68.037 ± 19.179 | 0.575 | 2.8929 | −7.5051 | 13.2909 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milosavljević, S.; Jovanović, M.; Rajković, Ž.; Radisavljević, V.; Šapić, T.; Šamanović, A.M.; Mladenović, R.; Đorđević, V.; Miljković, M.; Pajović, D.; et al. Analysis of Dento-Facial Parameters in the Young Population Using Digital Methods. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030453

Milosavljević S, Jovanović M, Rajković Ž, Radisavljević V, Šapić T, Šamanović AM, Mladenović R, Đorđević V, Miljković M, Pajović D, et al. Analysis of Dento-Facial Parameters in the Young Population Using Digital Methods. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):453. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030453

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilosavljević, Sonja, Milica Jovanović, Žaklina Rajković, Vladan Radisavljević, Tanja Šapić, Anđela Milojević Šamanović, Raša Mladenović, Vladan Đorđević, Milan Miljković, Danka Pajović, and et al. 2026. "Analysis of Dento-Facial Parameters in the Young Population Using Digital Methods" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030453

APA StyleMilosavljević, S., Jovanović, M., Rajković, Ž., Radisavljević, V., Šapić, T., Šamanović, A. M., Mladenović, R., Đorđević, V., Miljković, M., Pajović, D., Todić, J., & Milosavljević, M. (2026). Analysis of Dento-Facial Parameters in the Young Population Using Digital Methods. Diagnostics, 16(3), 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030453