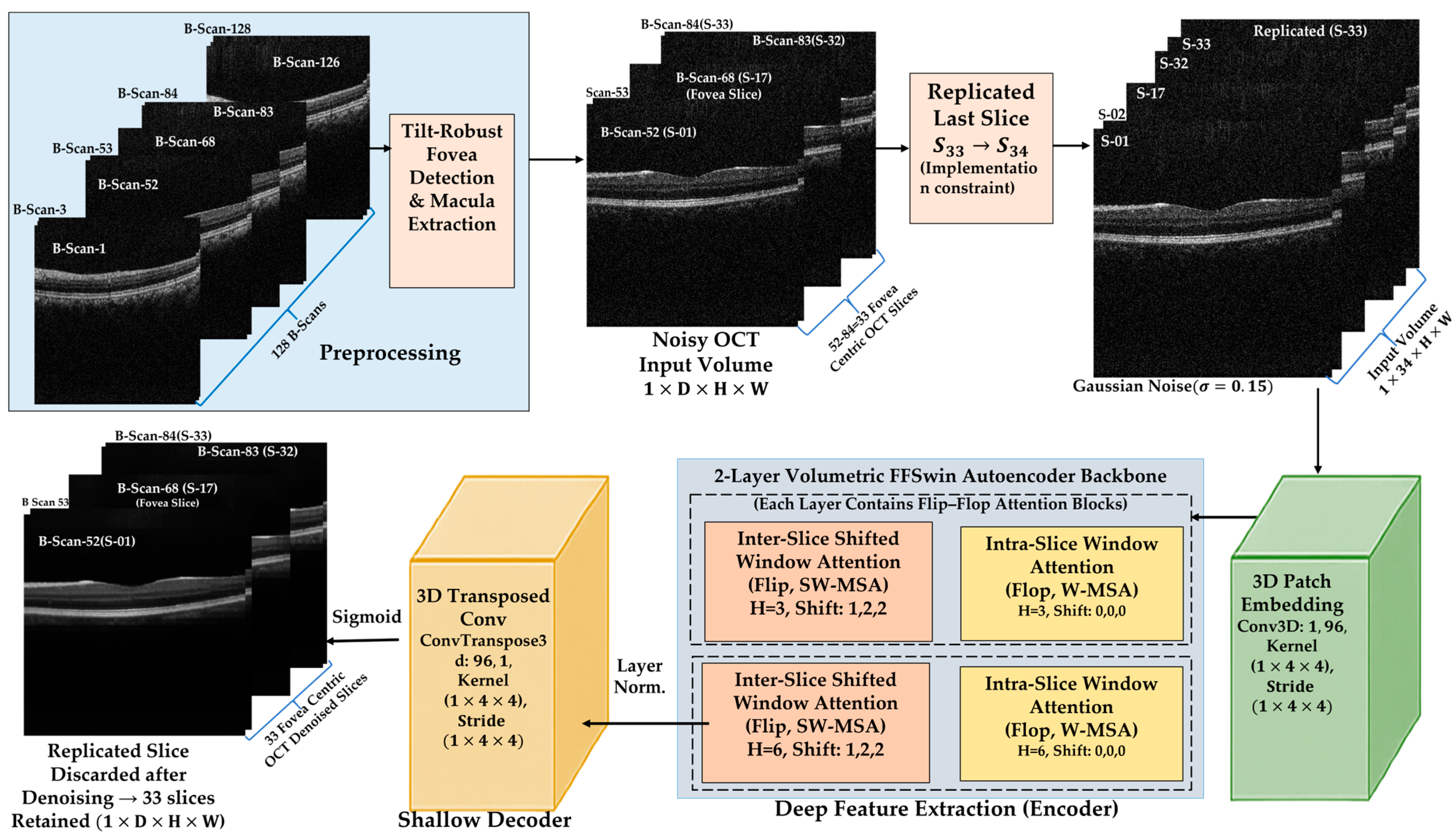

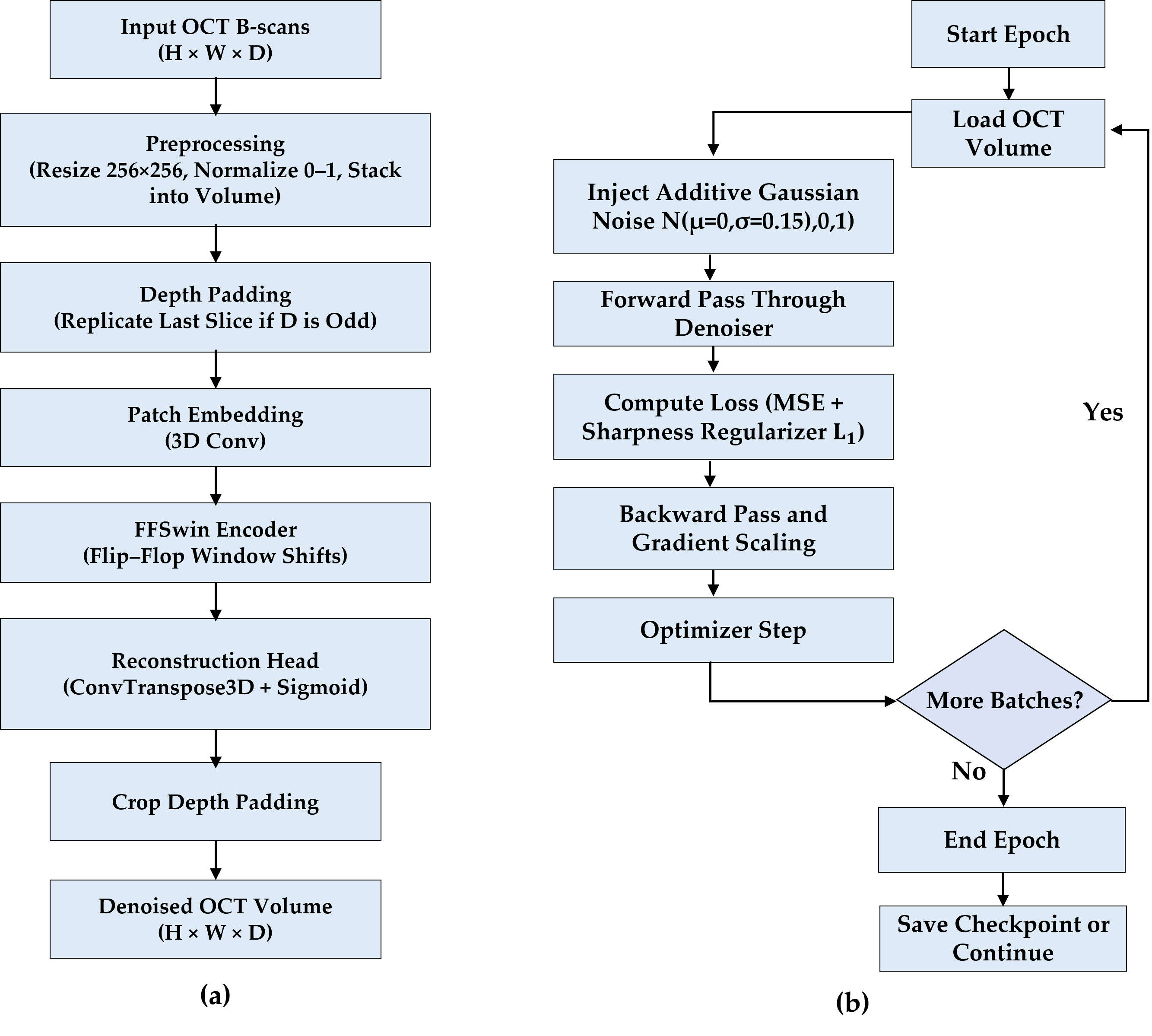

This section presents the experimental validation of the proposed BanglaOCT2025 dataset and the associated preprocessing pipeline. The results are organized into three parts. First, a summary of the statistical characteristics and clinical composition of the BanglaOCT2025 dataset to establish its representativeness and diagnostic relevance (

Section 3.1). Second, the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed constraint-based fovea-centric volume extraction algorithm are evaluated, which serves as the foundation for all subsequent analysis (

Section 3.2). Finally, the impact of the self-supervised volumetric denoising framework is analyzed through downstream diagnostic performance, statistical testing, reference-free metrics, and qualitative visual assessment (

Section 3.3).

All experiments were conducted on automatically extracted fovea-centered 33-slice OCT sub-volumes from raw 128-slice macular cubes, ensuring consistent anatomical alignment across patients and diagnostic categories.

3.2. Evaluation of Constraint-Based Fovea-Centric Volume Extraction

Accurate fovea localization is essential for macular analysis [

11], as AMD biomarkers are concentrated near the foveal pit. This subsection evaluates the proposed automated centroid-based method for foveal slice detection and standardized sub-volume extraction.

3.2.1. Robustness of Automated Foveal Slice Detection

The algorithm reliably identified the foveal slice across the dataset without manual input during deployment. By combining column-wise centroid analysis with a clinically motivated penalty constraint, the method remained robust to common acquisition artifacts, such as retinal tilt, uneven illumination, and pathological deformation. No boundary violations or extraction failures were observed after application of the anatomical constraints and boundary-aware windowing strategy.

Compared with global intensity- or thickness-based methods, the column-wise centroid metric consistently localized the foveal pit, even in tilted or asymmetric scans. Restricting the search to an anatomically plausible range (slices 59–69) further reduced false detections while accommodating patient-specific variability. Manual foveal confirmation was used only for validation; all reported results rely on the fully automated pipeline. No systematic failure patterns were observed across the evaluated volumes; rare extreme deviations occurred in isolated cases and were effectively handled by the enforced anatomical constraints and boundary-aware extraction strategy.

To quantitatively evaluate the reliability of automated fovea localization, clinician-selected foveal slices were compared with automated detections on an independent set of 50 anonymized OCT volumes. The mean absolute difference between automated and expert-selected foveal slices was 2.65 ± 3.26 slices (range: 0–23). This distribution indicates close overall agreement between automated and manual localization without evidence of systematic bias. Excluding a single extreme outlier case, the mean absolute slice difference decreased to 2.21 ± 1.54 slices (range: 0–7), confirming stable and consistent localization performance across the remaining cases.

3.2.2. Standardization of Macular Sub-Volumes

After fovea detection, a fixed 33-slice sub-volume (fovea ±16 slices) was extracted for each scan, ensuring anatomically consistent macular coverage while removing peripheral redundancy. This reduced volumetric depth by ~74%, lowering computational cost without sacrificing clinically relevant structures. Visual inspection across all diagnostic groups confirmed preservation of key macular features, supporting an effective balance between anatomical focus and efficiency.

3.2.3. Role of Fovea-Centric Extraction in Downstream Analysis

All denoising, classification, and evaluation experiments (reported in

Section 3.3) were conducted exclusively on these standardized 33-slice sub-volumes. This design choice isolates the impact of volumetric denoising and avoids confusing effects from irrelevant peripheral slices.

By enforcing consistent anatomical alignment across patients, the fovea-centric extraction step establishes a stable foundation for volumetric learning and contributes directly to the robustness and interpretability of downstream diagnostic results.

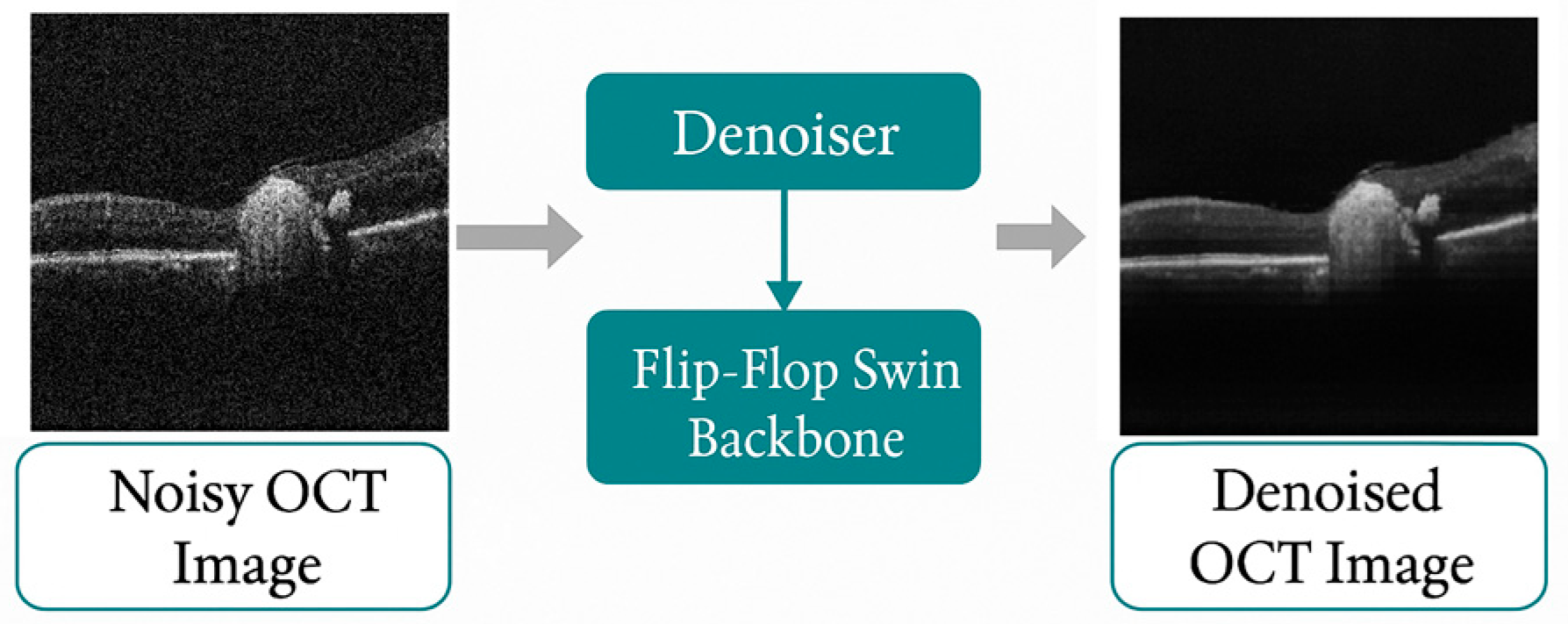

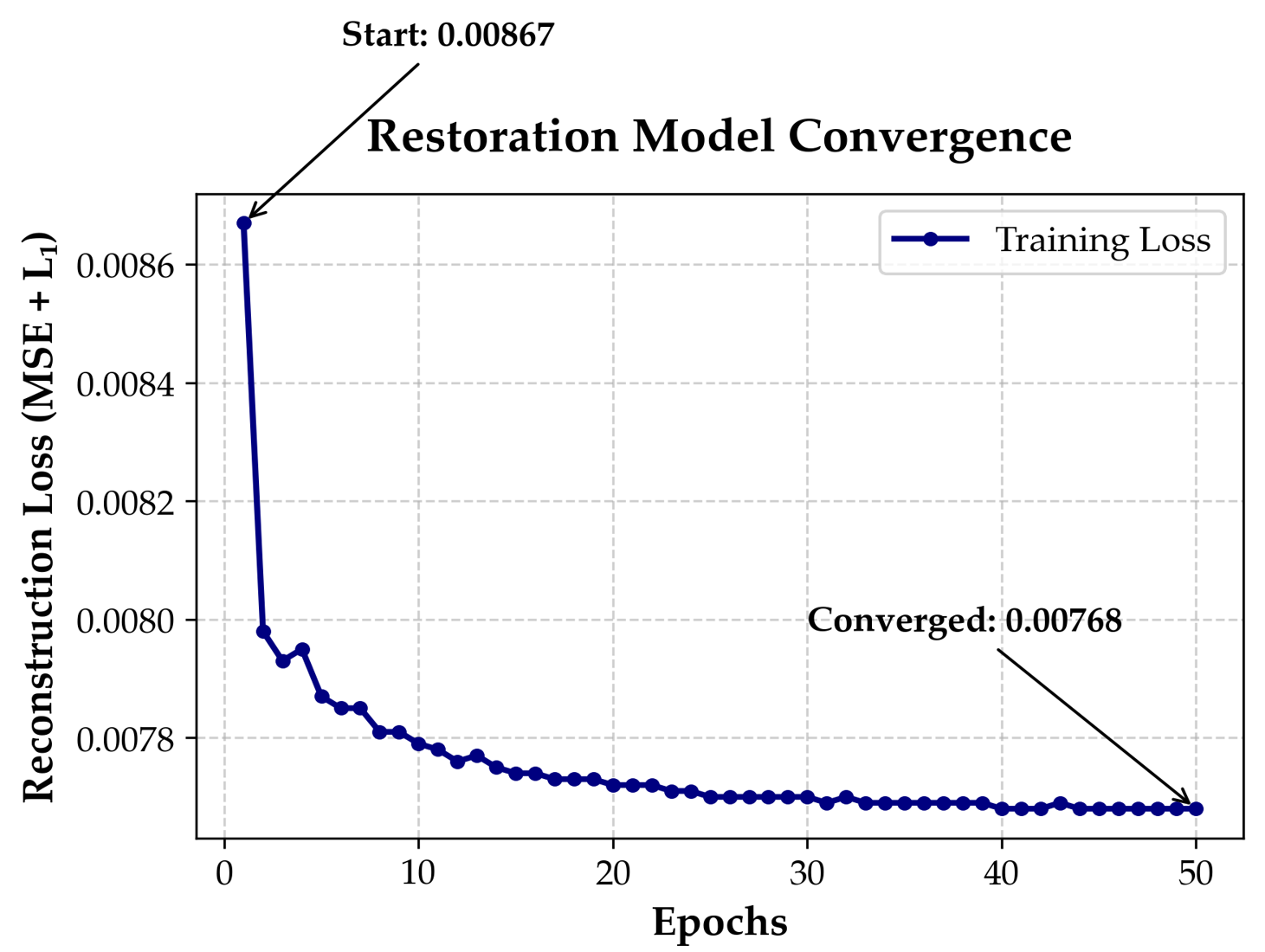

3.3. Self-Supervised Volumetric Restoration Framework Using FFSwin Backbone

It is essential to note that downstream classification performance is not a standalone sufficient metric for denoising quality in this study. Instead, classification results are reported as a complementary, task-oriented indicator that reflects whether clinically relevant features remain discriminative after restoration. Primary evaluation of the denoising framework is based on reference-free volumetric metrics, blinded clinical assessment, and paired statistical analysis.

3.3.1. Classification Performance on BanglaOCT2025 Dataset

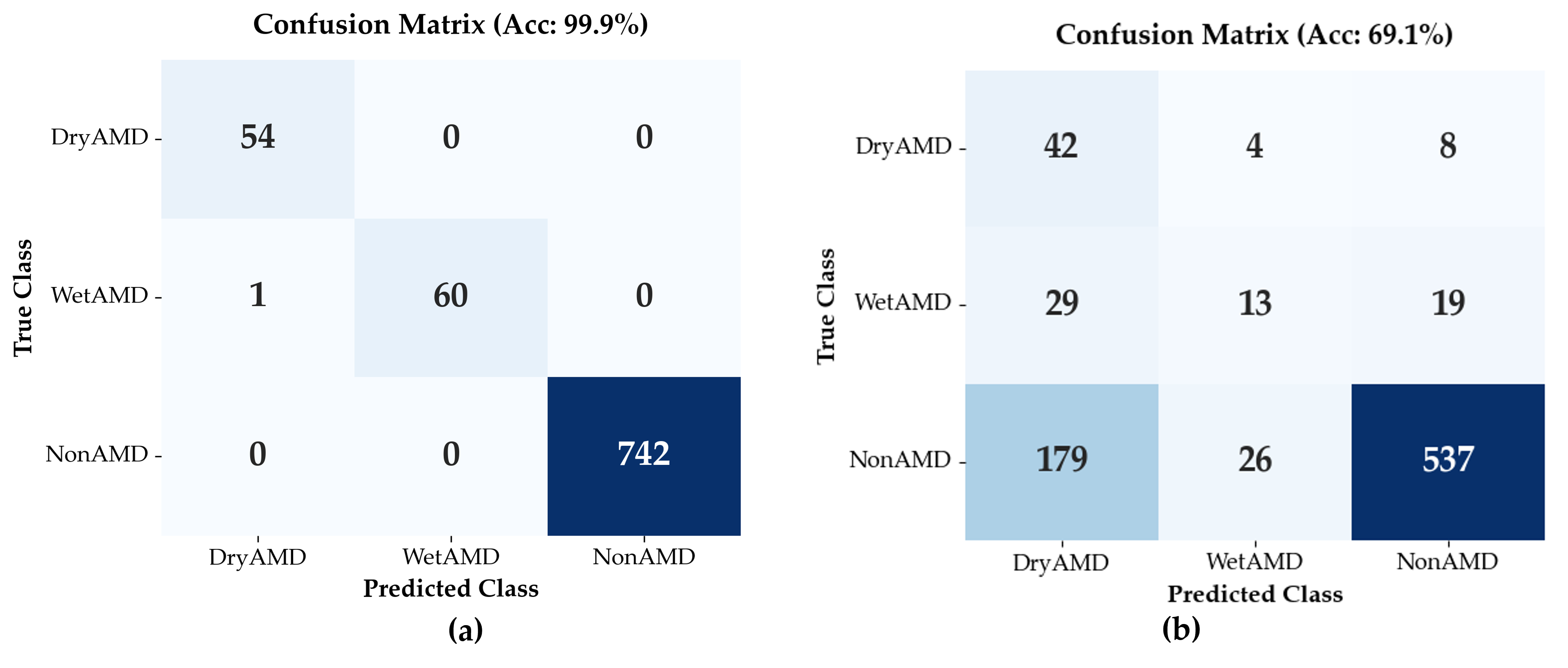

Classification performance of the Flip-Flop Swin Transformer (FFSwin) was assessed on BanglaOCT2025 using patient-wise evaluation. The dataset included 857 scans from 573 patients (54 DryAMD, 61 WetAMD, and 742 NonAMD), each represented by 33 fovea-centric B-scans. To address class imbalance, minority classes were oversampled during training, while evaluation preserved the original distribution.

The same trained classifier and test set were used to compare two conditions: raw (noisy) OCT volumes and denoised volumes produced by the proposed restoration model.

Performanceon Raw OCT Volumes: When evaluated on raw OCT volumes, the classifier achieved an overall validation accuracy of 69.08%; however, performance varied substantially across classes. Precision for the NonAMD category was high (0.95), indicating reliable identification of eyes without AMD. In contrast, WetAMD detection was markedly limited, with a recall of 0.21, indicating that most WetAMD cases were not correctly identified under noisy input conditions. This result highlights the sensitivity of WetAMD biomarkers to speckle noise and reduced image clarity, as summarized in

Table 6.

Here, the NonAMD category encompasses both normal eyes and other non-AMD retinal conditions. Accordingly, these results primarily reflect the system’s ability to distinguish AMD from non-AMD presentations in a screening-oriented setting, rather than fine-grained discrimination among heterogeneous non-AMD pathologies.

The macro-averaged F1-score was 0.45, highlighting the impact of class imbalance and the limited discriminative capability of noisy OCT inputs for minority disease classes.

Performance on Denoised OCT Volumes: All results in this subsection are based on validation using the original set of 857 real OCT volumes. When evaluated on denoised inputs, the trained classifier achieved a validation accuracy of 99.88%. Here, classification performance is used solely as a task-oriented probe of restoration quality, rather than as evidence of independent clinical generalization. The classifier was used as a fixed diagnostic probe with frozen weights and identical hyperparameters for both raw and denoised volumes, ensuring that performance differences reflect the impact of denoising rather than changes in model training. Importantly, because no independent patient-wise hold-out test set was available, the reported near-ceiling classification performance should be interpreted strictly as an upper-bound estimate of diagnostic signal recoverability under controlled, paired evaluation conditions.

As summarized in

Table 7, class-wise recall reached 1.00 for DryAMD, 0.98 for WetAMD, and 1.00 for NonAMD, with a macro-averaged F1-score of 0.99, indicating strong class separability despite pronounced class imbalance. In contrast, evaluation on the corresponding raw (noisy) volumes yielded a validation accuracy of 69.08%. Because both evaluations were performed on the same non-augmented dataset, this paired comparison isolates the effect of volumetric denoising on input signal quality.

Downstream classification accuracy is reported here as a secondary, task-oriented indicator of restoration effectiveness rather than a direct measure of image fidelity. The observed improvement reflects enhanced signal-to-noise characteristics and inter-slice consistency, not the creation of new diagnostic features. Together with blinded clinical validation and structure-preservation analysis (

Section 3.3.2), these findings suggest that volumetric denoising improves diagnostic visibility while preserving retinal anatomy. The near-ceiling accuracy should therefore be interpreted as an upper-bound estimate of diagnostic signal recoverability within BanglaOCT2025, rather than deployment-level performance.

3.3.2. Blinded Clinical Validation of Denoising

To complement algorithmic evaluation, a blinded qualitative clinical assessment was performed by an experienced retina specialist who was not involved in model development and was unaware of the processing status. A randomly selected subset of 27 OCT volumes spanning DryAMD, WetAMD, and NonAMD cases was reviewed. For each case, raw and denoised volumes were presented side-by-side in randomized order.

The clinician assessed preservation of key anatomical features (retinal layer integrity, foveal contour, RPE continuity, drusen morphology, and fluid-related signs) and the presence of artificial artifacts. The clinician independently scored each volume using a 5-point Likert scale for (i) preservation of pathological features (5 = best preserved, 1 = worst preserved) and (ii) presence of artificial features or artifacts (5 = severe artifacts, 1 = minimal artifacts). Denoised volumes achieved higher scores for pathology preservation (mean 4.39 vs. 3.30) and lower artifact scores (mean 1.31 vs. 2.39) compared to raw images, as shown in

Table 8. No artificial structures, exaggerated pathology, or anatomically implausible alterations were observed.

These findings indicate that the proposed volumetric denoising improves visual clarity while preserving clinically relevant retinal anatomy, reducing the likelihood that downstream performance gains arise from artificial feature amplification. We note that Gaussian noise was used as a self-supervised perturbation rather than a physical speckle model; broader quantitative benchmarking against alternative volumetric denoising methods remains an important direction for future work.

3.3.3. Denoising Effectiveness via Downstream Diagnostic Task

In the absence of noise-free ground-truth OCT images, the effectiveness of the proposed denoising approach was evaluated indirectly through its impact on a downstream diagnostic task, following a task-driven evaluation paradigm commonly adopted in medical image analysis [

21,

39].

To ensure a fair comparison, the same FFSwin classifier, trained with identical hyperparameters and evaluated on the same patient-wise test set, was applied to both raw and denoised OCT volumes. The difference between the two evaluation settings was the quality of the input data, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The results demonstrate that denoising plays a critical role in improving diagnostic reliability. While raw OCT data led to substantial misclassification of AMD subtypes, denoised OCT volumes enabled nearly perfect recognition of both DryAMD and WetAMD cases. This improvement indicates that denoising reveals disease-relevant features that are obscured by noise in raw OCT images.

Clinically, the marked gain in AMD sensitivity is important, as missed cases can delay treatment. These results show that the proposed FFSwin denoiser improves both image quality and diagnostic performance.

3.3.4. Class-Imbalance-Aware Analysis

BanglaOCT2025 shows a strong class imbalance: NonAMD cases comprise about 87% of the dataset, while DryAMD and WetAMD together account for 13%. In such settings, overall accuracy can be misleading, masking poor performance on minority classes.

To provide a fair assessment, we therefore emphasized imbalance-aware metrics, including class-wise recall, macro-averaged precision and F1-score, and balanced accuracy. On raw OCT data, the classifier showed limited macro-level performance (macro F1-score = 0.45), reflecting weak recognition of AMD subtypes. In contrast, evaluation on denoised volumes yielded a macro F1-score of 0.99, indicating consistently high performance across all classes.

Notably, the recall for DryAMD and WetAMD improved from 0.78 and 0.21 (raw OCT) to 1.00 and 0.98 (denoised OCT), respectively. This demonstrates that denoising disproportionately benefits minority disease classes by enhancing subtle pathological features that are otherwise suppressed by speckle noise [

15].

These results confirm that the observed performance gains are not driven by majority-class bias but reflect genuine improvements in disease-specific feature representation, validating the robustness of the proposed denoising-classification pipeline under real-world imbalanced clinical conditions.

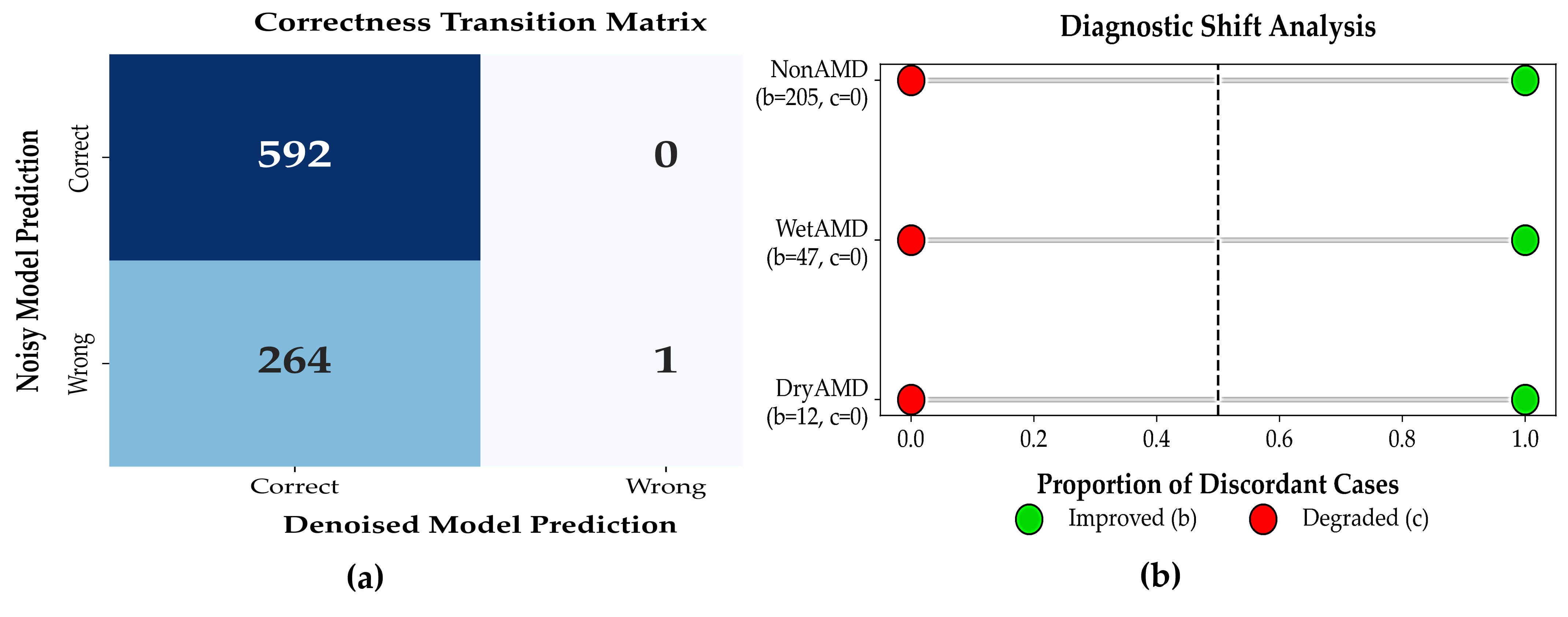

3.3.5. McNemar’s Test for Paired Diagnostic Outcomes

To evaluate whether denoising significantly affected patient-level diagnostic correctness, a paired McNemar test was conducted by comparing classifier predictions on raw (noisy) OCT volumes and their corresponding denoised versions for the same patients. The resulting contingency table is reported in

Table 9. Out of 857 cases, 592 were correctly classified under both conditions, 264 cases improved after denoising, 1 case was incorrectly classified under both conditions, and no cases showed degraded performance after denoising (c = 0).

This paired evaluation used the same trained classifier with frozen weights and identical OCT volumes before and after denoising, thereby isolating the effect of input-level signal enhancement. Although the absence of degraded cases may appear unusual in large clinical datasets, it reflects the controlled evaluation setting in which denoising operates purely as a preprocessing step and does not introduce new class-discriminative information. We nevertheless acknowledge that this outcome may indicate a degree of coupling between the denoising and classification stages, and that McNemar’s test in this context evaluates relative consistency rather than independent generalization. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted as an upper-bound estimate of achievable improvement under idealized conditions.

The McNemar test demonstrated a highly significant difference between the two conditions (continuity-corrected

exact binomial

,

Table 10). This strong statistical significance arises from the large imbalance between improved and degraded outcomes (264 vs. 0), indicating that denoising consistently increases diagnostic correctness in this paired setting. No evidence of systematic performance degradation was observed.

Overall, these findings support that the denoising module enhances diagnostic signal quality without introducing clinically harmful misclassifications, while highlighting the need for future validation using independent test sets and cross-scanner data to further assess robustness and generalizability.

Patient-level Diagnostic Impact of Denoising: Patient-level correctness transition heatmap comparing noisy and denoised OCT-based diagnoses.

Denoising resulted in substantial recovery of previously misclassified patients without introducing diagnostic errors, as shown in

Figure 6a. Forest plot showing proportions of improved and degraded diagnoses after denoising. All discordant cases favored improvement, with no observed degradation as shown in

Figure 6b.

3.3.6. Performance Evaluation

Class-Imbalance Aware Diagnostic Performance: To address severe class imbalance in the BanglaOCT2025 dataset (DryAMD = 54, WetAMD = 61, NonAMD = 742), class-wise confusion matrices were aggregated using a one-vs-rest strategy. This analysis reveals that denoising substantially improves sensitivity across all disease categories while maintaining or improving specificity, as shown in

Table 11.

The most noticeable gain was observed for WetAMD, where sensitivity increased from 0.213 to 0.984, effectively eliminating missed diagnoses. In this study, no increase in false positives was observed after denoising, confirming that performance gains were not achieved at the expense of diagnostic specificity.

Due to the severe class imbalance, evaluation relied primarily on class-imbalance aware metrics. When noisy OCT volumes were applied to the FFSwin classification model, the model achieved a balanced accuracy of 0.5715, macro F1-score of 0.4496, and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) of 0.2912, indicating limited robustness under noise, as shown in

Table 12.

After applying the proposed self-supervised denoising pipeline, performance improved dramatically. Balanced accuracy increased to 0.9945, macro F1-score to 0.9942, and MCC to 0.9952. Cohen’s kappa rose from 0.2426 to 0.9952, indicating near-perfect agreement beyond chance, as shown in

Table 12.

Notably, WetAMD sensitivity increased from 0.2131 to 0.9836, representing a critical clinical improvement in detecting the most vision-threatening condition, as shown in

Table 13. These gains confirm that denoising substantially enhances diagnostic reliability across all disease categories without bias toward the majority NonAMD class.

After applying the proposed self-supervised denoising pipeline, performance improved dramatically. Balanced accuracy increased to 0.9945, macro F1-score to 0.9942, and MCC to 0.9952. Cohen’s kappa rose from 0.2426 to 0.9952, indicating near-perfect agreement beyond chance.

Interpretation of Performance Metrics: Prior to denoising, the classifier failed to detect the majority of WetAMD cases, representing a high-risk scenario for missed progressive disease. After denoising, the model correctly identified nearly all disease cases across categories, substantially reducing missed diagnoses. This improvement is especially important for WetAMD, where timely detection directly influences treatment outcomes. Notably, the gain in sensitivity did not come at the expense of specificity; false positives were rare, indicating that denoising enhances diagnostic confidence without increasing unnecessary referrals.

Under noisy conditions, positive AMD predictions were often unreliable. Following denoising, precision exceeded 98% for all disease classes, suggesting that positive predictions can be interpreted with high clinical confidence. The marked improvement in F1-score reflects a balanced reduction in both missed cases and false alarms, confirming that performance gains are not driven by class imbalance or trivial predictions.

Improvements in balanced accuracy further demonstrate that denoising enables consistent performance across DryAMD, WetAMD, and NonAMD cases, rather than favoring the majority class. Near-perfect values of MCC and Cohen’s kappa indicate strong agreement with expert annotations and confirm that the observed accuracy is robust and unbiased. Together, these findings support the role of volumetric denoising as a key enabler of reliable OCT-based AMD diagnosis.

Overall, class-imbalance-aware metrics show that the FFSwin-based denoising approach markedly improves diagnostic performance by reducing missed AMD cases while maintaining near-perfect specificity. The close agreement with expert annotations highlights the importance of volumetric denoising for reliable OCT-based AMD diagnosis.

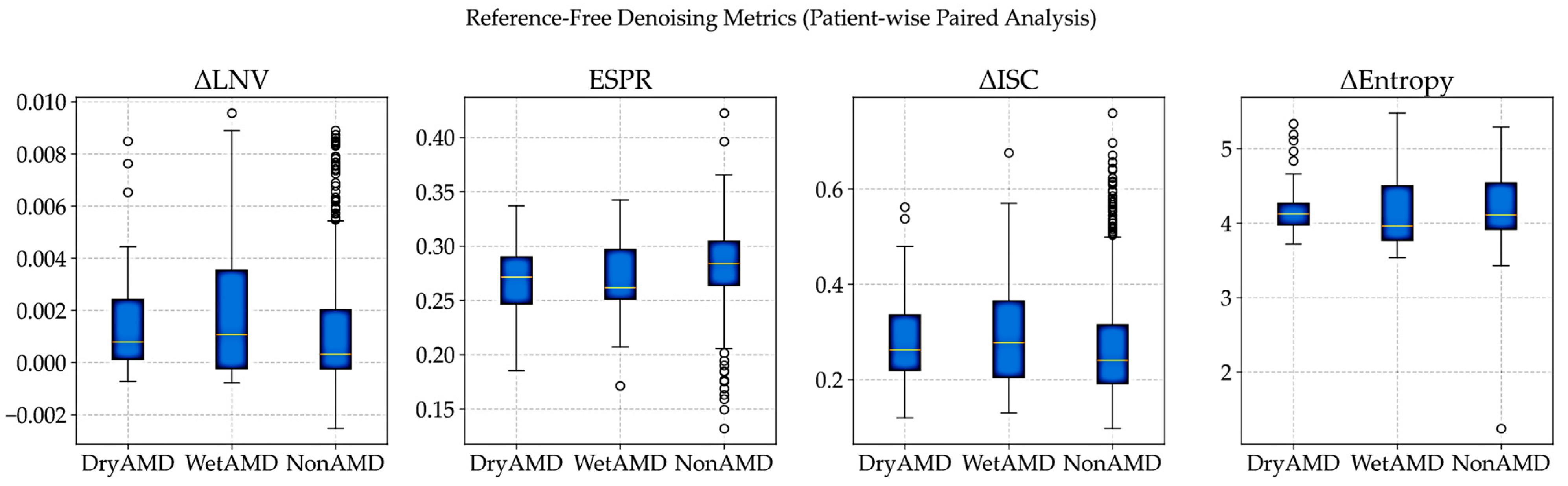

3.3.7. Reference-Free Evaluation of Denoising on Real OCT Volumes

As the noise-free OCT references are unavailable in clinical practice, denoising performance was evaluated using patient-wise, reference-free metrics that compare noisy and denoised volumes, following established real-world evaluation protocols [

8,

37,

39].

Noise reduction was assessed using local variance, while structural preservation and volumetric coherence were evaluated through edge strength and inter-slice consistency. All metrics were computed on paired patient scans, with noisy volumes resized to match denoised images, ensuring fair and spatially aligned comparisons.

Evaluation Metrics: Because noise-free OCT references are not available, denoising performance was evaluated using complementary reference-free metrics, following standard practices in biomedical image analysis when clean ground truth data are unavailable [

8,

21,

33,

39]. Changes in local noise variance (ΔLNV) were used to measure residual speckle noise, with lower values indicating effective noise reduction without over-smoothing [

32,

33]. The Edge Strength Preservation Ratio (ESPR), computed from Sobel gradients, was used to assess how well anatomically meaningful boundaries were preserved after denoising [

42,

43]. Volumetric coherence was evaluated using the change in inter-slice correlation (ΔISC), which measures improvements in structural consistency between adjacent B-scans along the depth axis [

11]. Finally, changes in Shannon entropy (Δ Entropy) were used to assess reductions in randomness while preserving meaningful retinal structures [

44,

45].

All metrics were computed per patient and then aggregated class-wise for DryAMD, WetAMD, and NonAMD cohorts. Class-wise mean reference-free denoising metrics are summarized in

Table 14.

Visual Distribution Analysis: The patient-wise distributions in

Figure 7 show that denoising performance is consistent across diagnostic groups despite strong class imbalance. Similar ΔISC and ESPR patterns across classes indicate stable preservation of inter-slice coherence and anatomical edges, supporting the robustness of the proposed approach under real-world clinical variability.

Clinical Relevance and Downstream Impact: The gains in volumetric coherence and edge preservation are reflected in downstream performance, where the same FFSwin classifier achieves 99.88% accuracy on BanglaOCT2025 after denoising. Reference-free analysis confirms that this improvement arises from meaningful noise suppression and structural stabilization rather than artificial smoothing. Overall, the proposed FFSwin-based denoising framework demonstrates robust behavior across resolutions and disease categories, preserves anatomical integrity, and provides a reliable preprocessing step for clinical OCT analysis.

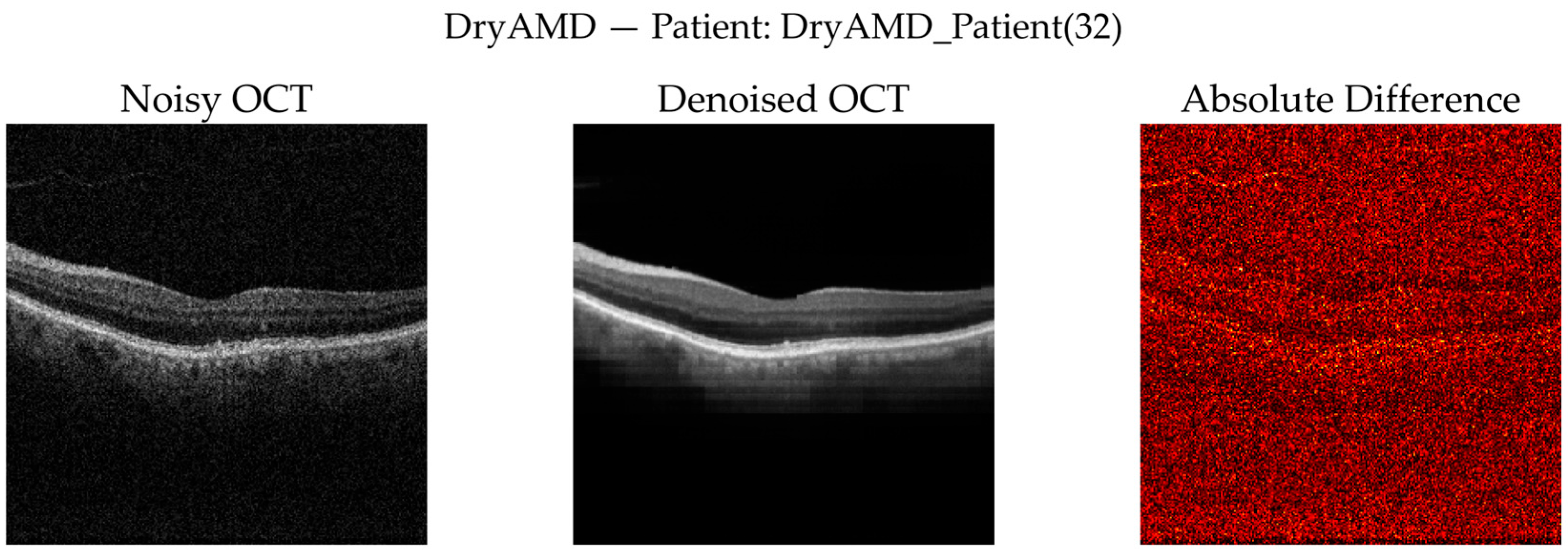

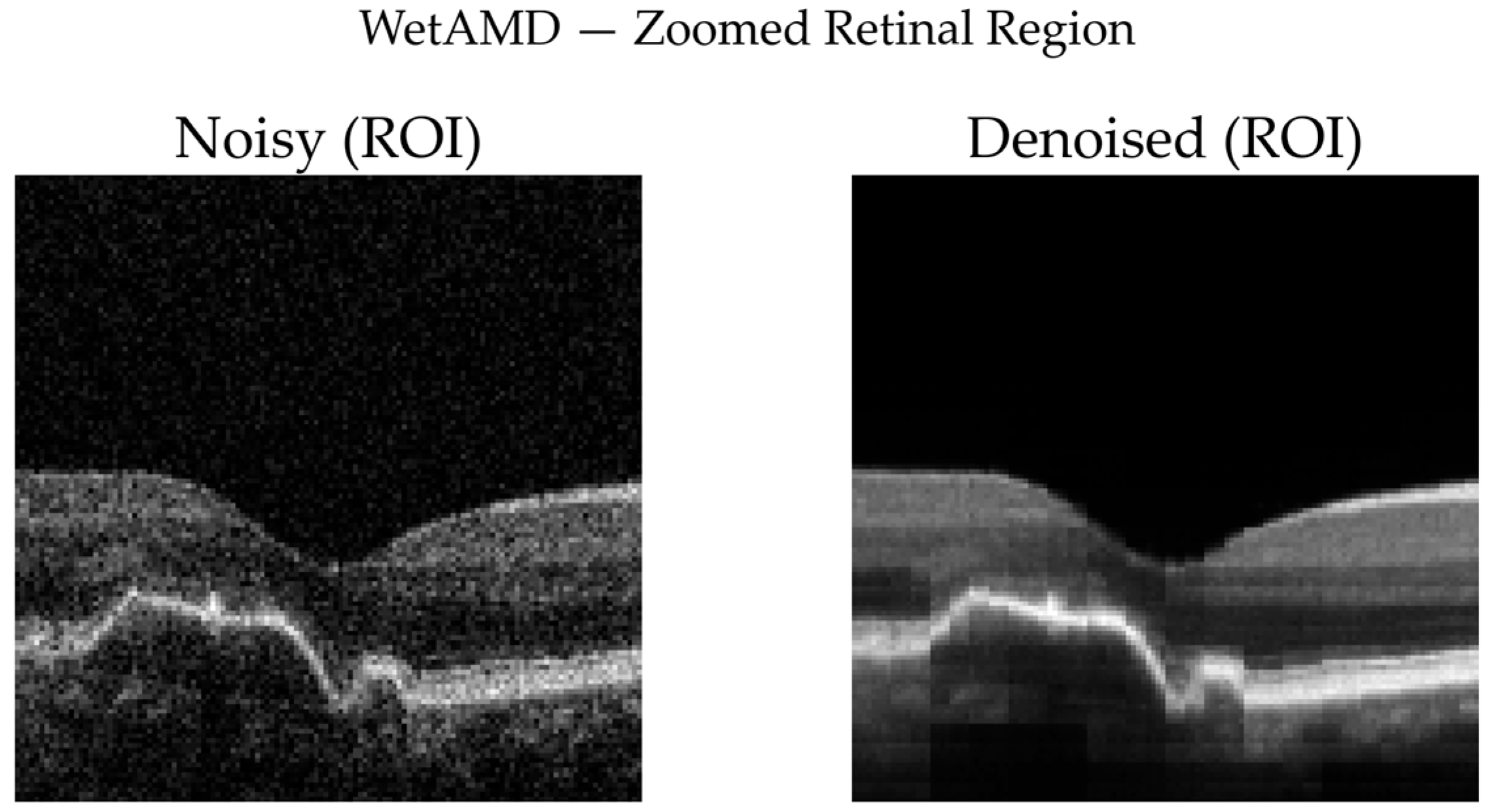

3.3.8. Qualitative Visual Assessment of Denoising Performance

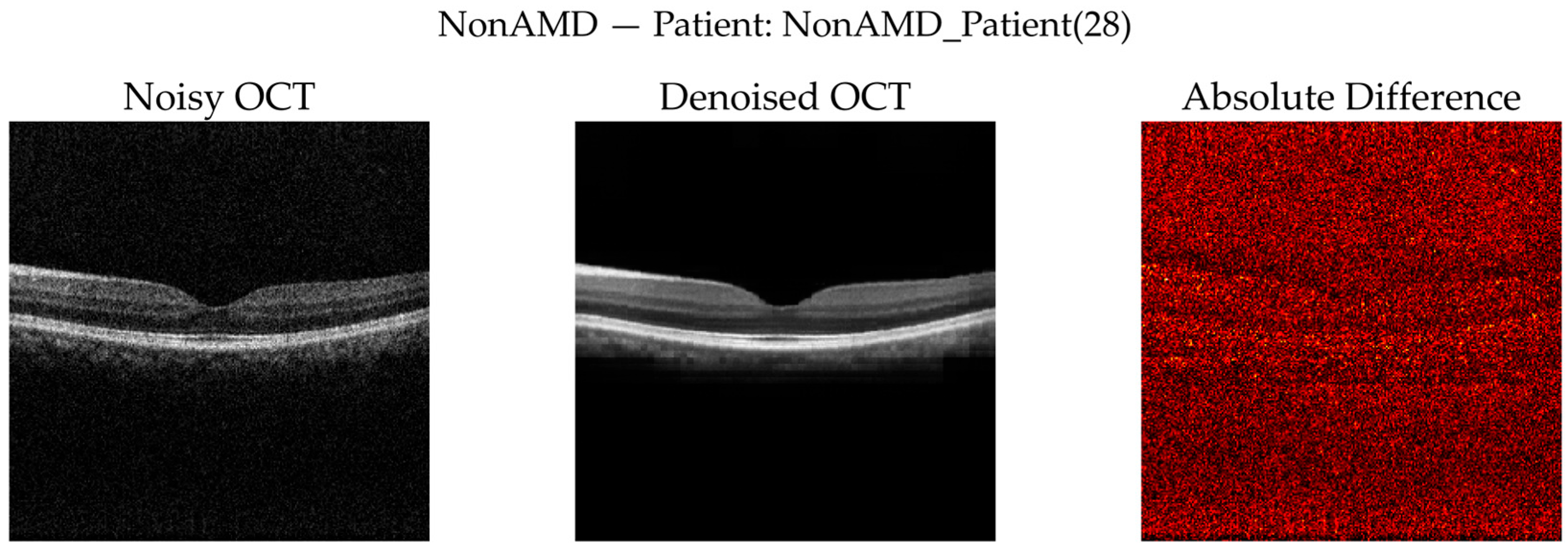

To complement quantitative analysis, representative OCT B-scans from DryAMD, WetAMD, and NonAMD cases were visually examined.

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 compare the noisy inputs, FFSwin-denoised outputs, absolute difference maps, and zoomed retinal regions of interest. Across all categories, denoising markedly reduces speckle noise—particularly in the vitreous and deeper retinal layers—while preserving clinically relevant retinal anatomy. Difference maps indicate that the restoration primarily targets high-frequency noise with minimal impact on underlying retinal structure.

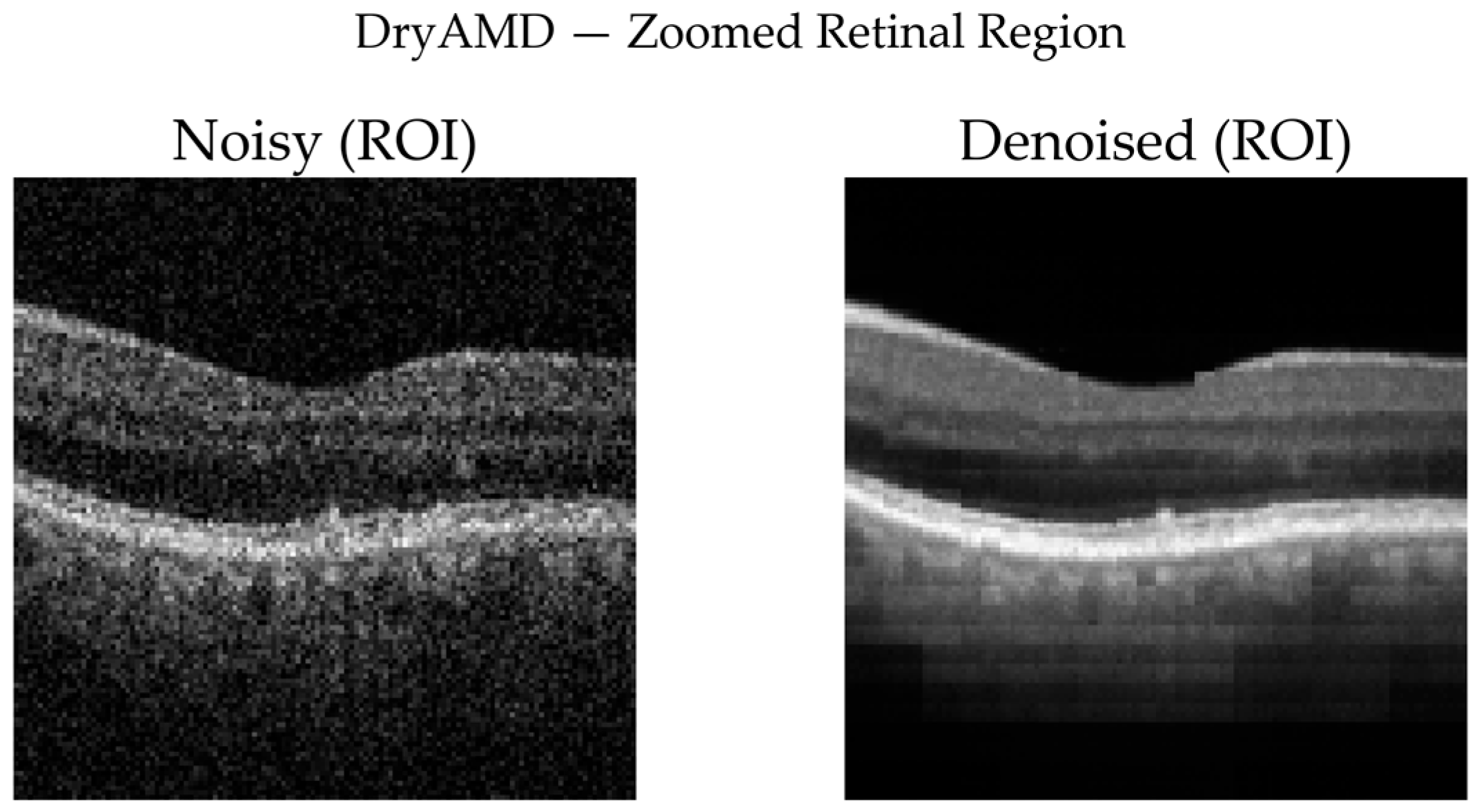

DryAMD Cases: As illustrated in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, FFSwin-based denoising visibly reduces speckle noise and improves layer contrast in DryAMD scans. Retinal boundaries, particularly in the outer retina, appear more continuous and less fragmented. The difference maps show that intensity changes are mainly confined to homogeneous background regions, indicating effective noise suppression without altering retinal structure. Zoomed views further confirm improved intra-layer uniformity while preserving overall retinal morphology, with no evidence of artificial edges or spurious features.

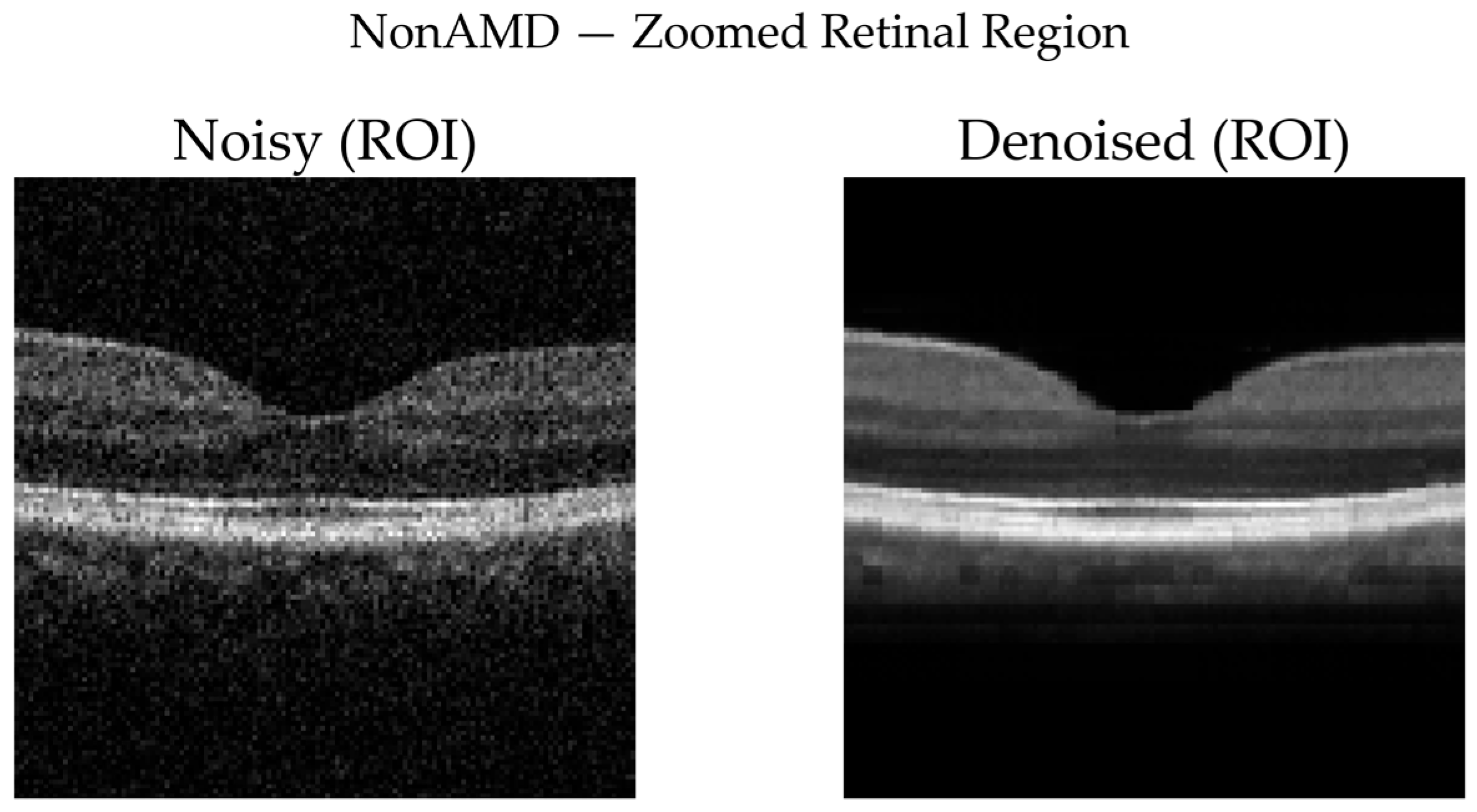

NonAMD Cases: Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show that denoising reduces speckle noise and improves layer uniformity while preserving normal foveal contour and retinal thickness. Difference maps indicate that changes are primarily noise-related rather than structural.

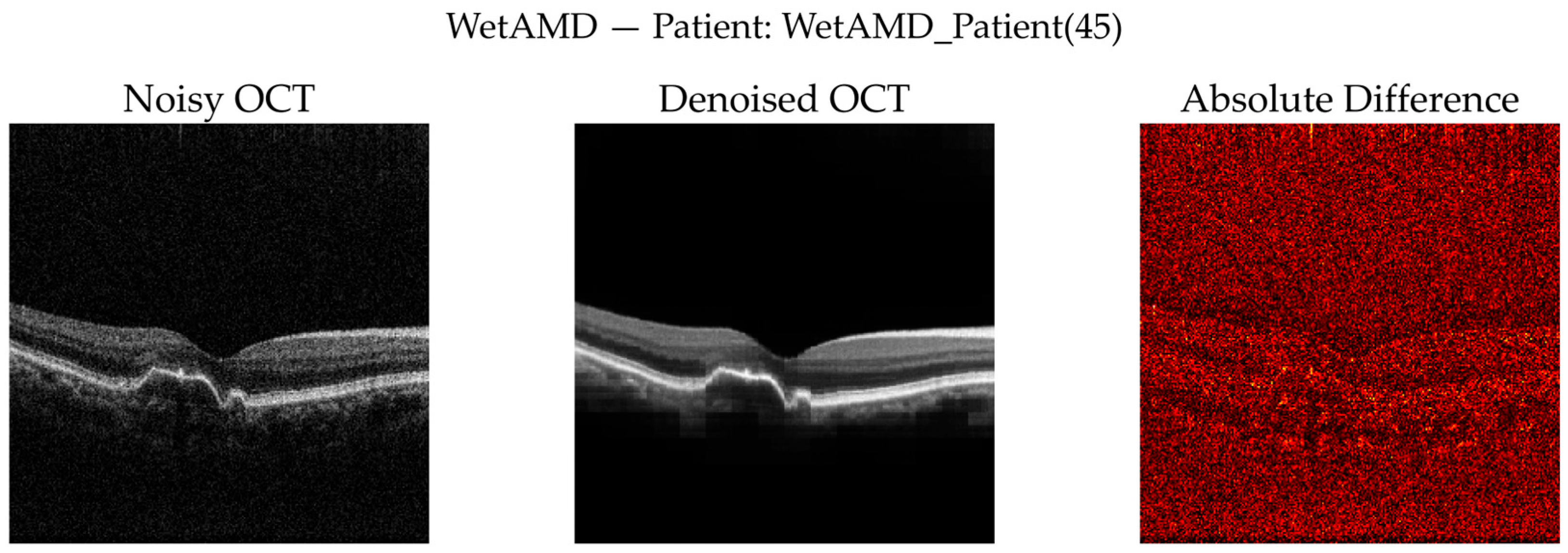

WetAMD Cases: WetAMD examples (

Figure 12) represent the most challenging scenario due to the presence of highly reflective lesions, fluid accumulations, and shadowing artifacts. Despite these complexities, the denoised image retains critical pathological features such as hyperreflective regions and subretinal fluid contours, while substantially reducing background speckle.

In the zoomed ROI (

Figure 13), the denoised output exhibits improved contrast between lesion regions and surrounding tissue, which may facilitate downstream classification and clinical interpretation. The difference map again indicates that the denoising primarily targets stochastic noise rather than disease-specific signal patterns.

Across all diagnostic categories, the qualitative results show effective speckle noise reduction without over-smoothing, preservation of retinal layers and disease-related structures, absence of visible artifacts, and consistency with improvements observed in reference-free metrics and downstream classification performance.

These visual findings corroborate the quantitative improvements reported earlier and support the suitability of the proposed FFSwin-based denoising framework for real-world OCT analysis, particularly in settings where clean reference images are unavailable.

3.3.9. Why Quantitative Metrics (PSNR, SSIM, MSE) Are Not Included

The quantitative denoising metrics are intentionally omitted for the following reasons:

- •

No available clean ground truth for real OCT volumes: Self-supervised denoising cannot be directly benchmarked using reference-based metrics.

- •

The purpose of denoising is functional, not comparative: The FFSwin denoiser is used as a preprocessing backbone for AMD classification.

- •

Indirect validation through diagnostic accuracy: Our classifier trained on denoised volumes achieves 99.88% accuracy, which strongly indicates structural preservation and useful noise suppression.

- •

Novel dataset (BanglaOCT2025): No public baselines exist for fair cross-model comparison.

The goal is diagnostic enhancement, not denoising benchmarking.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that fovea-centric volumetric abstraction combined with self-supervised denoising fundamentally alters the diagnostic utility of OCT data. Across quantitative, statistical, and qualitative evaluations, the proposed pipeline consistently improves structural coherence, suppresses speckle noise without anatomical distortion, and enables near-perfect downstream AMD classification under severe class imbalance.