MRI in Chronic Pudendal Neuralgia: Diagnostic Criteria and Associated Pathologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- •

- Non-fat saturated axial, coronal, and sagittal T2-weighted fast spin-echo (FSE): TR 4000 ms, TE eff 100 ms, turbo factor 13, thickness 3 mm, parallel imaging SENSE AF 1.5.

- •

- Fat saturated axial T2-weighted FSE: TR 4500 ms, TE eff 100 ms, turbo factor 13, thickness 3 mm. TR 4000 ms, ET eff 100 ms, turbo factor 13, thickness 3 mm, parallel imaging SENSE AF 1.5, fat saturation obtained by spectral pre-saturation with inversion recovery (SPIR) strong.

- •

- Non-fat saturated Axial T1-weighted FSE: TR 450–550 ms, TE eff 10–15, turbo factor 3–5, thickness: 3 mm, parallel imaging SENSE AF 1.5.

- •

- Coronal and sagittal SSTSE T2-weighted myelography for detection of Tarlov cyst.

3. Results

- (1)

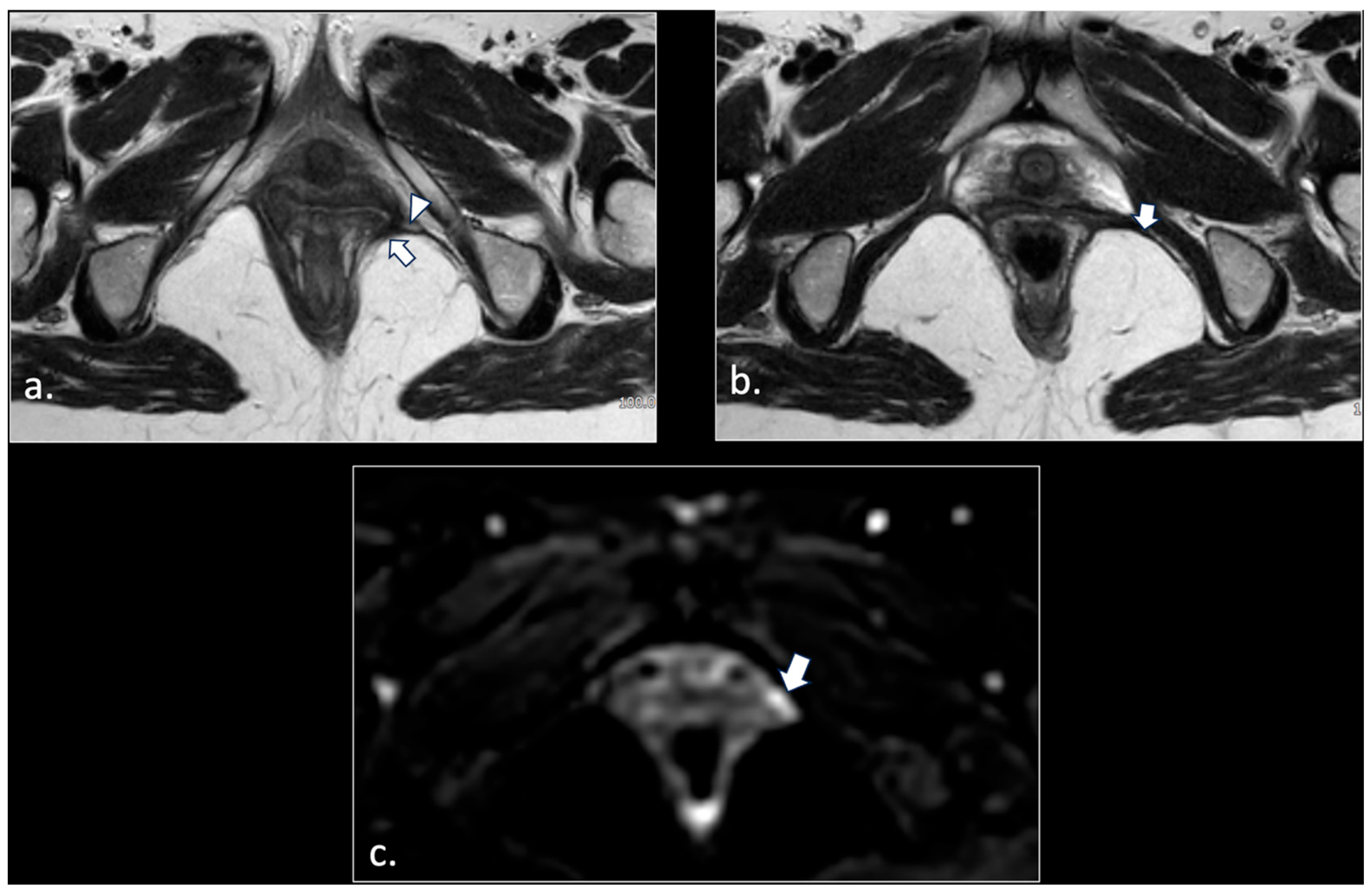

- Hemorrhagic Tarlov’s cyst of the sacrum (1 patient);

- (2)

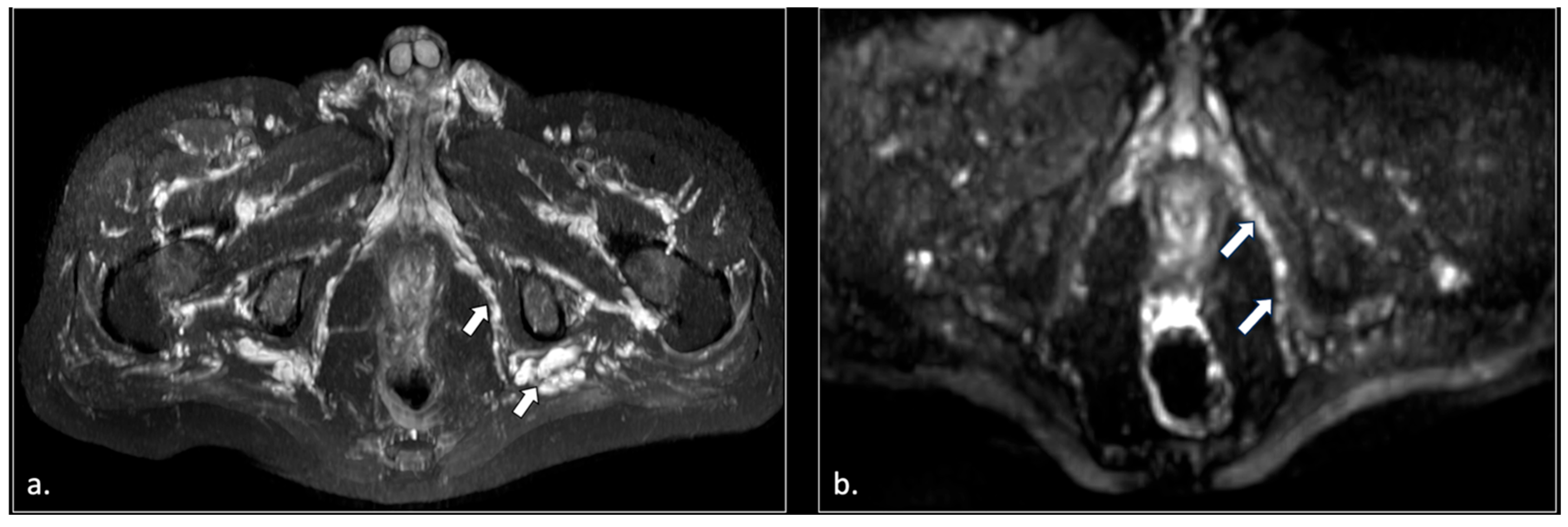

- Unilateral or bilateral hypertrophy of the pyriform muscle (4 patients);

- (3)

- Unilateral or bilateral lesions of the sacrotuberous and/or sacrospinous ligaments (interligamentous space) (5 patients);

- (4)

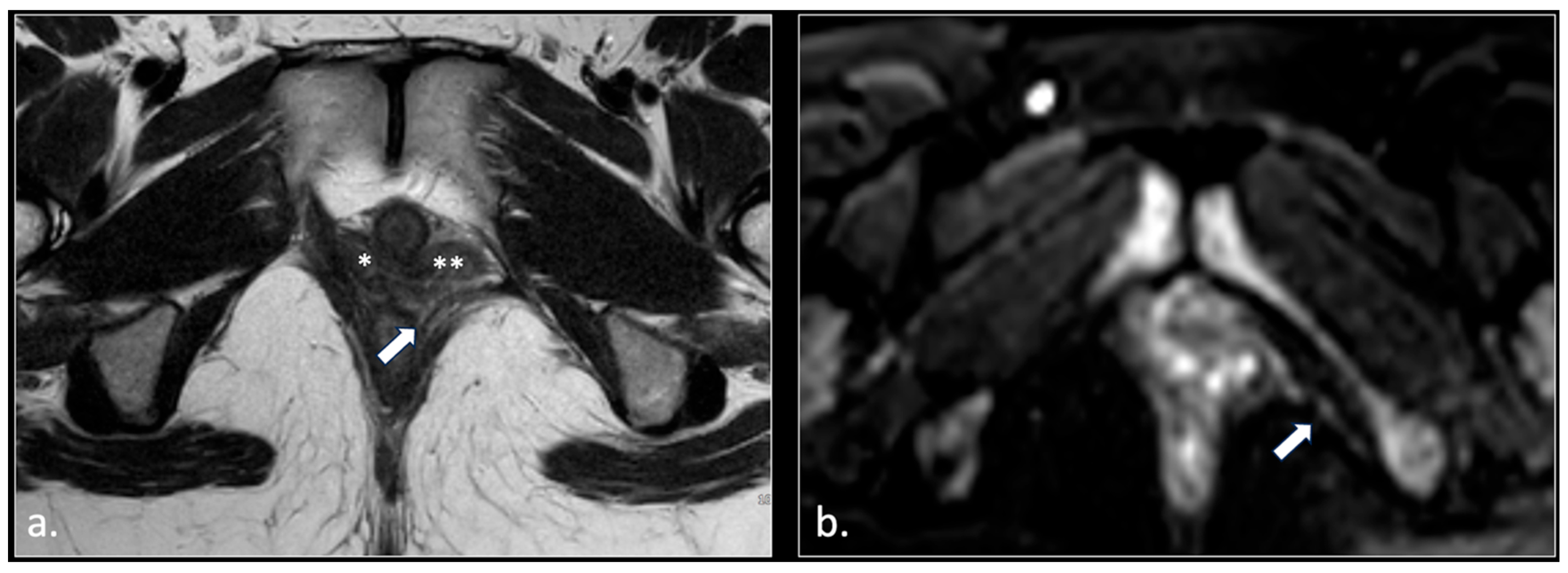

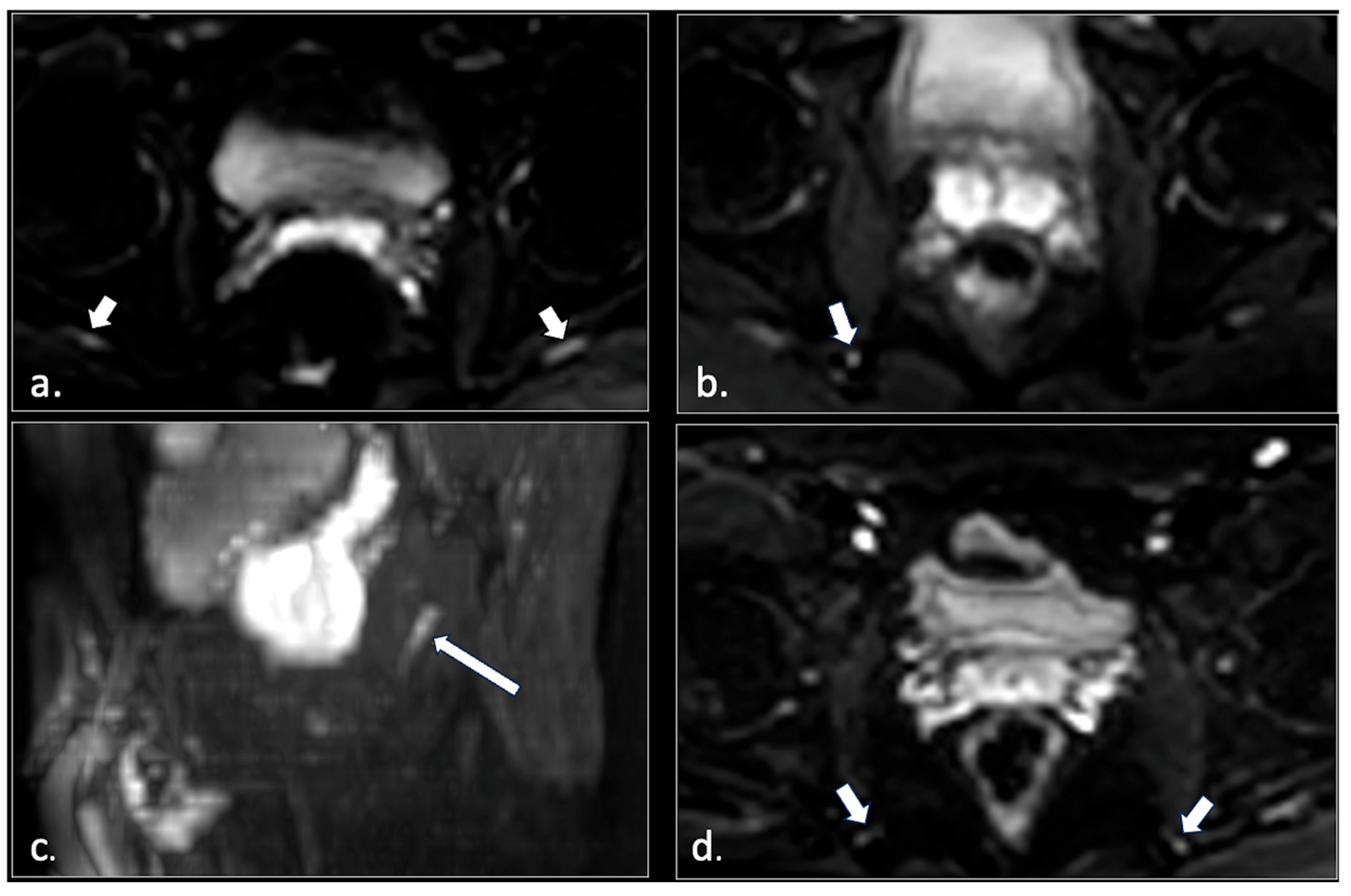

- Unilateral rupture of puborectal and/or pubococcygeal muscle (4 patients);

- (5)

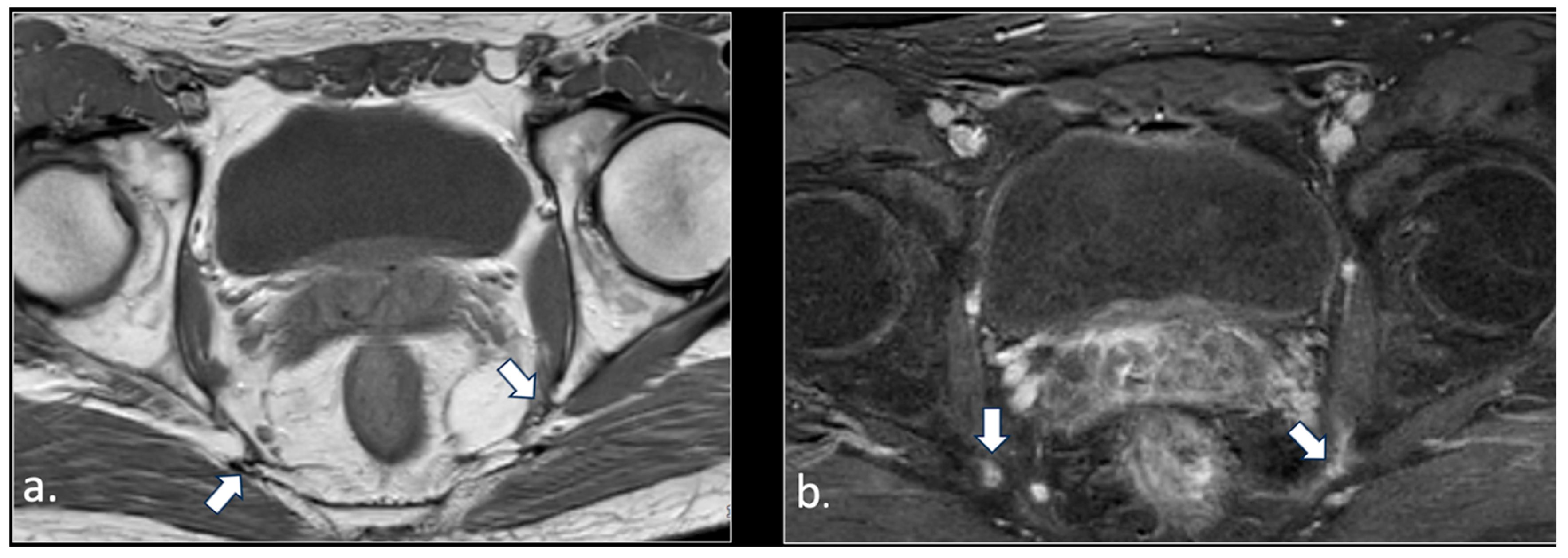

- Perineal fibrosis involving Alcok’s canal (4 patients);

- (6)

- Giant cyst of the prostatic utricle (1 patient);

- (7)

- Pudendal nerve schwannomas (2 patients);

- (8)

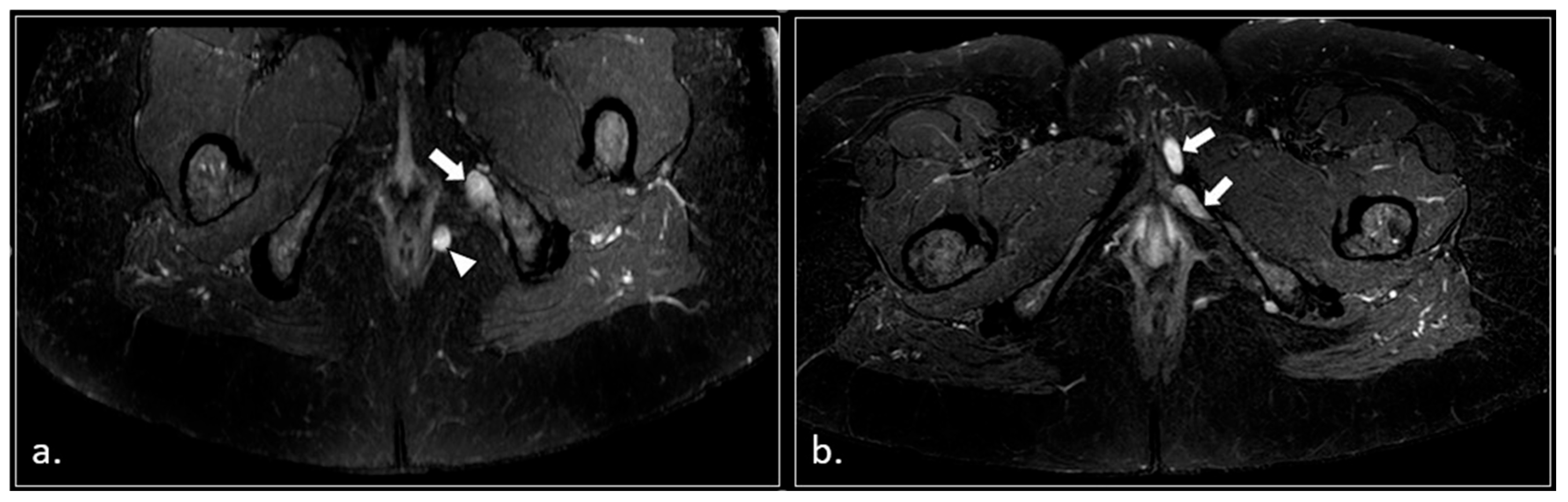

- Varices of the pudendal vein in the Alcock canals (2 patients).

4. Discussion

- (1)

- The topographical distribution of the pain (from the anus to the penis or clitoris);

- (2)

- Exacerbation of pain when sitting;

- (3)

- Lack of awakening during the night;

- (4)

- Lack of objective sensory alterations;

- (5)

- Response to pudendal nerve block.

Limitations

- The absence of a correlation with the pudendal nerve block test. All patients included in this study presented with a strong clinical and anamnestic suspicion of pudendal neuralgia and were referred for pelvic MRI as part of their diagnostic pathway. Assessment of the diagnostic performance of MRI compared with pudendal nerve block as a reference standard was beyond the scope of the present work and would require dedicated future studies. Nevertheless, pelvic MRI performed using a dedicated imaging protocol, as in our study, may potentially contribute to the diagnostic process, support clinical decision-making, and be helpful in selected cases in which the nerve block results are inconclusive or the procedure is difficult to perform. Furthermore, MRI may aid in identifying the underlying etiology of pudendal neuralgia.

- All patients were studied with a 1.5 Tesla scanner. Since a 3 Tesla scanner improves the spatial resolution [13], we could expect better results with such a type of technology signal. Further studies performed with a 3 Tesla scanner on groups of patients with pudendal neuralgia should be obtained.

- We did not explore the potential role of new techniques such as 3D T2-weighted sequence with blood signal suppression by a pre-saturation pulse, which is a promising technique for studying small nerve branches without interference from small vessel signaling [38,39,40,41]. To the best of our knowledge, reports on the use of this approach in patients with pudendal neuralgia have not yet been published. However, there are some clear advantages in our approach, based on diffusion neurography in patients with pudendal neuralgia. These advantages are:(1) The technique is available on every 1.5 and 3 Tesla scanners;(2) It is solid and reliable in absence of metallic orthopedic hardware;(3) The administration of gadolinium is not required.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leslie, S.W.; Antolak, S.; Feloney, M.P.; Soon-Sutton, T.L. Pudendal Neuralgia; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hibner, M.; Desai, N.; Robertson, L.J.; Nour, M. Pudendal neuralgia. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Robert, R.; Amarenco, G.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Rigaud, J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol. Urodyn. 2008, 27, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, R.; Prat-Pradal, D.; Labat, J.J.; Bensignor, M.; Raoul, S.; Rebai, R.; Leborgne, J. Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: Role of the pudendal nerve. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 1998, 20, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploteau, S.; Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Levesque, A.; Robert, R.; Nizard, J. New concepts on functional chronic pelvic and perineal pain: Pathophysiology and multidisciplinary management. Discov. Med. 2015, 19, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bautrant, E.; de Bisschop, E.; Vaini-Elies, V.; Massonnat, J.; Aleman, I.; Buntinx, J.; de Vlieger, J.; Di Constanzo, M.; Habib, L.; Patroni, G.; et al. La prise en charge moderne des névralgies pudendales. A partir d’une série de 212 patientes et 104 interventions de décompression [Modern algorithm for treating pudendal neuralgia: 212 cases and 104 decompressions]. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 32, 705–712. (In French) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Antolak, S.J., Jr.; Hough, D.M.; Pawlina, W.; Spinner, R.J. Anatomical basis of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: The ischial spine and pudendal nerve entrapment. Med. Hypotheses 2002, 59, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, D.M.; Wittenberg, K.H.; Pawlina, W.; Maus, T.P.; King, B.F.; Vrtiska, T.J.; Farrell, M.A.; Antolak, S.J., Jr. Chronic perineal pain caused by pudendal nerve entrapment: Anatomy and CT-guided perineural injection technique. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003, 181, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzGerald, M.P.; Kotarinos, R. Rehabilitation of the short pelvic floor. I: Background and patient evaluation. Int. Urogynecol J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003, 14, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Leslie, S.W.; Singh, P. Pudendal Nerve Entrapment Syndrome; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thiel, P.; Kobylianskii, A.; McGrattan, M.; Lemos, N. Entrapped by pain: The diagnosis and management of endometriosis affecting somatic nerves. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 95, 102502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; McKenna, C.A.; Wadhwa, V.; Thawait, G.K.; Carrino, J.A.; Lees, G.P.; Dellon, A.L. 3T magnetic resonance neurography of pudendal nerve with cadaveric dissection correlation. World J. Radiol. 2016, 8, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wadhwa, V.; Hamid, A.S.; Kumar, Y.; Scott, K.M.; Chhabra, A. Pudendal nerve and branch neuropathy: Magnetic resonance neurography evaluation. Acta Radiol. 2017, 58, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, A.G. Diagnosis and management of pudendal nerves entrapment syndrome: Impact of MR neurography and open MR guided injections. Neurosurg. Q. 2008, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piloni, V.; Bergamasco, M.; Chiapperin, A.; Mazzucco, M.; Felici, T.; Andreatini, J.; Nucera, N.; Freddi, E. Magnetic resonance imaging of pudendal nerve: Technique and results. Pelviperineology 2020, 39, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piloni, V.; Bergamasco, M.; Bregolin, F.; Buzzolani, M.; Carraro, R.; Chiapperin, A.; de Togni, L.; Frigo, N.; Giomo, G.; Mazzucco, M.; et al. MR imaging of the pudendal nerve: A one-year experience on an outpatient basis. Pelviperineology 2014, 33, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, J.; Scott, K.; Xi, Y.; Ashikyan, O.; Chhabra, A. Role of 3 Tesla MR Neurography and CT-guided Injections for Pudendal Neuralgia: Analysis of Pain Response. Pain Physician 2019, 22, E333–E344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Nasralla, M.; Pron, G.; Almohaimede, K.; Schievink, W. Management of Tarlov cysts: An uncommon but potentially serious spinal column disease—Review of the literature and experience with over 1000 referrals. Neuroradiology 2024, 66, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.; Lin, Y.; Tan, E.T.; Sneag, D.B. MR Neurography of the Lumbosacral Plexus: Technique and Disease Patterns. RadioGraphics 2025, 45, e240099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, B.; Yang, Z.; Mao, L.; Lin, E. 3-T imaging of the cranial nerves using three-dimensional reversed FISP with diffusion-weighted MR sequence. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2008, 27, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohritz, A.; Dellon, A.L. Valleix’s Sign. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2024, 93, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafik, A.; el-Sherif, M.; Youssef, A.; Olfat, E.S. Surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its clinical implication. Clin. Anat. 1995, 8, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapletal, J.; Nanka, O.; Halaska, M.J.; Maxova, K.; Hajkova Hympanova, L.; Krofta, L.; Rob, L. Anatomy of the pudendal nerve in clinically important areas: A pictorial essay and narrative review. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2024, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.G.; Talbott, J.; Chin, C.T.; Kliot, M. Peripheral nerve imaging. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2016, 136, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz Neto, F.J.; Kihara Filho, E.N.; Miranda, F.C.; Rosemberg, L.A.; Santos, D.C.B.; Taneja, A.K. Demystifying MR Neurography of the Lumbosacral Plexus: From Protocols to Pathologies. BioMed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9608947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; Madhuranthakam, A.J.; Andreisek, G. Magnetic resonance neurography: Current perspectives and literature review. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneag, D.B.; Daniels, S.P.; Geannette, C.; Queler, S.C.; Lin, B.Q.; de Silva, C.; Tan, E.T. Post-Contrast 3D Inversion Recovery Magnetic Resonance Neurography for Evaluation of Branch Nerves of the Brachial Plexus. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 132, 109304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, F.L.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Schmidt, M.H.; Weinstein, P.R. Diagnosis and management of sacral Tarlov cysts. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg. Focus 2003, 15, E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.M.; Khanna, R.; Kalinkin, O.; Castellanos, M.E.; Hibner, M. Evaluating the discordant relationship between Tarlov cysts and symptoms of pudendal neuralgia. Am. J. Obs. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 70.e1–70.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, T.; Hendrikse, J.; Yamashita, T.; Mali, W.P.; Kwee, T.C.; Imai, Y.; Luijten, P.R. Diffusion-weighted MR neurography of the brachial plexus: Feasibility study. Radiology 2008, 249, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E. Imaging of peripheral nerve causes of chronic buttock pain and sciatica. Clin. Radiol. 2021, 76, 626.e1–626.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Noguerol, T.; Montesinos, P.; Hassankhani, A.; Bencardino, D.A.; Barousse, R.; Luna, A. Technical Update on MR Neurography. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2022, 26, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.; Lin, Y.; Tan, E.T.; Sneag, D. Magnetic Resonance Neurography of the Lumbosacral Plexus. Radiol. Clin. North. Am. 2023, 62, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Tan, E.T.; Campbell, G.; Colucci, P.G.; Singh, S.; Lan, R.; Wen, Y.; Sneag, D.B. Improved 3D DESS MR neurography of the lumbosacral plexus with deep learning and geometric image combination reconstruction. Skelet. Radiol. 2024, 53, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Gu, Y.; Xu, L. Enhanced MR neurography of the lumbosacral plexus with robust vascular suppression and improved delineation of its small branches. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 129, 109128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; Kanchustambham, P.; Mogharrabi, B.; Ratakonda, R.; Gill, K.; Xi, Y. MR Neurography of Lumbosacral Plexus: Incremental Value Over XR, CT, and MRI of L Spine with Improved Outcomes in Patients With Radiculopathy and Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 57, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foesleitner, O.; Sulaj, A.; Sturm, V.; Kronlage, M.; Godel, T.; Preisner, F.; Nawroth, P.P.; Bendszus, M.; Heiland, S.; Schwarz, D. Diffusion MRI in Peripheral Nerves: Optimized b Values and the Role of Non-Gaussian Diffusion. Radiology 2022, 302, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Cruyssen, F.; Croonenborghs, T.M.; Hermans, R.; Jacobs, R.; Casselman, J. 3D Cranial Nerve Imaging, a Novel MR Neurography Technique Using Black-Blood STIR TSE with a Pseudo Steady-State Sweep and Motion-Sensitized Driven Equilibrium Pulse for the Visualization of the Extraforaminal Cranial Nerve Branches. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupp, E.; Cervantes, B.; Sollmann, N.; Treibel, F.; Weidlich, D.; Baum, T.; Rummeny, E.J.; Zimmer, C.; Kirschke, J.S.; Karampinos, D.C. Improved Brachial Plexus Visualization Using an Adiabatic iMSDE-Prepared STIR 3D TSE. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2019, 29, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Harrison, C.; Mariappan, Y.K.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Chhabra, A.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Madhuranthakam, A.J. MR Neurography of Brachial Plexus at 3.0 T with Robust Fat and Blood Suppression. Radiology 2017, 283, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lin, Y.; Carrino, J.A. An updated review of magnetic resonance neurography for plexus imaging. Korean J. Radiol. 2023, 24, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, J.M.; Laing, N.G.; Kennerson, M.L.; Ravenscroft, G. Genetics of inherited peripheral neuropathies and the next frontier: Looking backwards to progress forwards. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Etiological Category | Causes | Pathophysiological Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-pelvic | Anatomical entrapment | Entrapment within Alcock’s canal; compression between sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments; anatomical nerve variants | Chronic mechanical compression |

| Muscular and myofascial | Obturator internus hypertonicity; levator ani spasm; pelvic floor myofascial pain | Dynamic compression, ischemia, neurogenic inflammation | |

| Gynecological | Deep infiltrating endometriosis; post-surgical adhesions; large uterine fibroids | Infiltration, traction, or extrinsic compression | |

| Urological | Chronic prostatitis | Inflammatory neuropathy | |

| Colorectal | Chronic proctitis; pelvic abscesses or fistulas | Direct nerve irritation or fibrosis | |

| Vascular | Pelvic venous congestion; pelvic varices | Pulsatile or static vascular compression | |

| Neoplastic | Pelvic tumors (rectal, prostate, gynecological) | Direct infiltration or mass effect | |

| Iatrogenic | Gynecological, urological, and colorectal surgery; mesh implantation; post-prostatectomy changes | Direct nerve injury, fibrosis, or entrapment | |

| Extra-pelvic | Mechanical compression | Entrapment at the lesser sciatic foramen; distal perineal branch compression | Distal nerve entrapment |

| Postural, functional, and sport-related | Prolonged sitting; sedentary lifestyle; lumbopelvic imbalance; cycling; horseback riding; sports with pelvic overload | Repetitive microtrauma; chronic compression or vibration-induced neuropathy | |

| Traumatic | Pelvic trauma; ischiopubic fractures; perineal falls | Direct nerve damage | |

| Obstetric | Prolonged vaginal delivery; instrumental delivery | Nerve stretches and ischemic injury | |

| Extra-pelvic surgical | Anal or perineal surgery; hemorrhoidectomy; episiotomy | Partial nerve injury or post-surgical fibrosis | |

| Infectious/dermatological | Sacral herpes zoster; deep perineal infections | Inflammatory neuropathy | |

| Radicular/central | Lumbosacral radiculopathy (S2–S4); sacral canal stenosis | Referred neuropathic pain | |

| Central sensitization | Chronic pelvic pain syndrome | Amplification of nociceptive signaling |

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 81 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 53 (65.4%) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 28 (34.6%) |

| Age range (years) | 19–59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gaeta, M.; Turturici, S.; Galletta, K.; Geremia, C.; Tuscano, A.; Gaeta, A.; Cavallaro, M.; Silipigni, S.; Granata, F. MRI in Chronic Pudendal Neuralgia: Diagnostic Criteria and Associated Pathologies. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020326

Gaeta M, Turturici S, Galletta K, Geremia C, Tuscano A, Gaeta A, Cavallaro M, Silipigni S, Granata F. MRI in Chronic Pudendal Neuralgia: Diagnostic Criteria and Associated Pathologies. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020326

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaeta, Michele, Sofia Turturici, Karol Galletta, Carmelo Geremia, Attilio Tuscano, Aurelio Gaeta, Marco Cavallaro, Salvatore Silipigni, and Francesca Granata. 2026. "MRI in Chronic Pudendal Neuralgia: Diagnostic Criteria and Associated Pathologies" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020326

APA StyleGaeta, M., Turturici, S., Galletta, K., Geremia, C., Tuscano, A., Gaeta, A., Cavallaro, M., Silipigni, S., & Granata, F. (2026). MRI in Chronic Pudendal Neuralgia: Diagnostic Criteria and Associated Pathologies. Diagnostics, 16(2), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020326