Efficacy of Transcatheter Renal Arterial Embolization to Contract Renal Size and Increase Muscle Mass in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

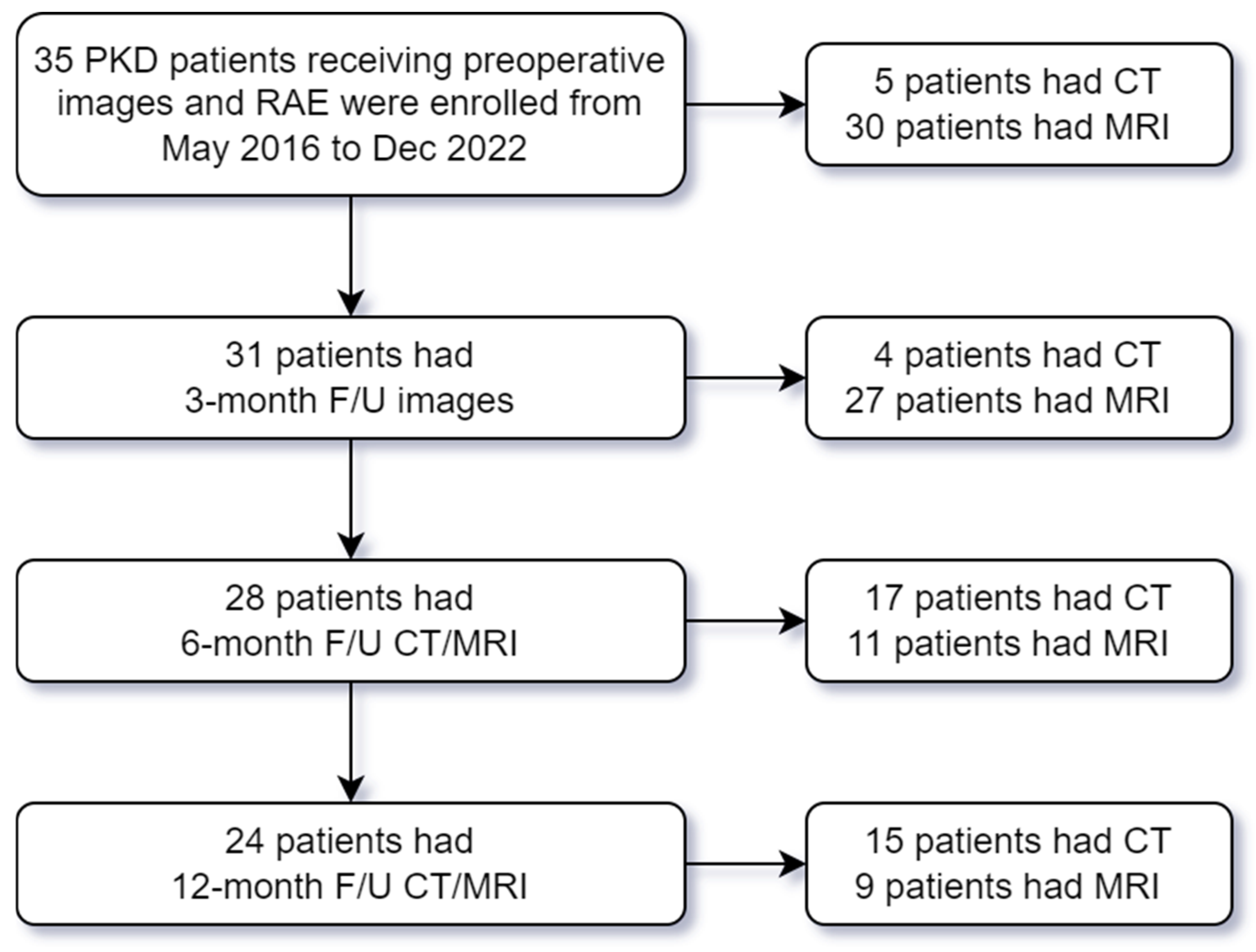

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Variables and Imaging Acquisition

2.3. Imaging Processing

2.4. Renal Artery Embolization (RAE)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

3.2. TKV and Muscle Mass Change After RAE

3.3. Subgroup Analysis Stratified by the Presence of Sarcopenia and Sex

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| PKD | Polycystic kidney disease |

| TKV | Total kidney volume |

| RAE | Renal artery embolization |

| PM | Psoas muscle |

| PS | Paraspinal muscle |

| L3 | The third lumbar vertebral |

| BH | Body height |

| NTUH | National Taiwan University Hospital |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| BW | Body weight |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| AC | Abdominal circumference |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| TR | Repetition time |

| TE | Time to echo |

| HASTE | Half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo |

| L | Longitudinal length |

| W | Maximal width |

| D | Maximal depth |

References

- Pereira, R.A.; Cordeiro, A.C.; Avesani, C.M.; Carrero, J.J.; Lindholm, B.; Amparo, F.C.; Amodeo, C.; Cuppari, L.; Kamimura, M.A. Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease on conservative therapy: Prevalence and association with mortality. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoyama, N.; Qureshi, A.R.; Avesani, C.M.; Lindholm, B.; Bàràny, P.; Heimbürger, O.; Cederholm, T.; Stenvinkel, P.; Carrero, J.J. Comparative associations of muscle mass and muscle strength with mortality in dialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Kim, S.G.; Oh, J.E.; Lee, Y.K.; Noh, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Song, Y.R. Impact of sarcopenia on long-term mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Mitch, W.E. Mechanisms of muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2014, 10, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, J.J.; Chmielewski, M.; Axelsson, J.; Snaedal, S.; Heimbürger, O.; Bárány, P.; Suliman, M.E.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P.; Qureshi, A.R. Muscle atrophy, inflammation and clinical outcome in incident and prevalent dialysis patients. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, F.C.; Santos, I.S.; Umpierre, D.; Bohlke, M.; Hallal, P.C. Effects of exercise in the whole spectrum of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Clin. Kidney J. 2015, 8, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taskapan, H.; Baysal, O.; Karahan, D.; Durmus, B.; Altay, Z.; Ulutas, O. Vitamin D and muscle strength, functional ability and balance in peritoneal dialysis patients with vitamin D deficiency. Clin. Nephrol. 2011, 76, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, A.M.; Ellis, C.D.; Shintani, A.; Booker, C.; Ikizler, T.A. IL-1β receptor antagonist reduces inflammation in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, S.; Mochizuki, T.; Muto, S.; Hanaoka, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Narita, I.; Nutahara, K.; Tsuchiya, K.; Tsuruya, K.; Kamura, K.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for polycystic kidney disease 2014. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2016, 20, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Lai, T.S.; Chen, Y.M.; Chen, C.M.; Yang, S.C.; Liang, P.C. Quantification of Abdominal Muscle Mass and Diagnosis of Sarcopenia with Cross-Sectional Imaging in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease: Correlation with Total Kidney Volume. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubara, Y.; Katori, H.; Tagami, T.; Tanaka, S.; Yokota, M.; Matsushita, Y.; Takemoto, F.; Imai, T.; Inoue, S.; Kuzuhara, K.; et al. Transcatheter renal arterial embolization therapy on a patient with polycystic kidney disease on hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1999, 34, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubara, Y.; Tagami, T.; Sawa, N.; Katori, H.; Yokota, M.; Takemoto, F.; Inoue, S.; Kuzuhara, K.; Hara, S.; Yamada, A. Renal contraction therapy for enlarged polycystic kidneys by transcatheter arterial embolization in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002, 39, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwabe, T.; Ubara, Y.; Sekine, A.; Ueno, T.; Yamanouchi, M.; Hayami, N.; Hoshino, J.; Kawada, M.; Hiramatsu, R.; Hasegawa, E.; et al. Effect of renal transcatheter arterial embolization on quality of life in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitpierre, F.; Cornelis, F.; Couzi, L.; Lasserre, A.S.; Tricaud, E.; Le Bras, Y.; Merville, P.; Combe, C.; Ferriere, J.M.; Grenier, N. Embolization of renal arteries before transplantation in patients with polycystic kidney disease: A single institution long-term experience. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 3263–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Tatto, B.; Gogeneata, I.; Ohana, M.; Thaveau, F.; Caillard, S.; Chakfe, N.; Lejay, A.; Georg, Y. Arterial Embolization of Polycystic Kidneys for Heterotopic Transplantation. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2022, 29, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuhara, Y.; Nishio, S.; Morita, K.; Abo, D.; Hasegawa, Y.; Yuasa, N.; Mochizuki, T.; Soyama, T.; Oba, K.; Shirato, H.; et al. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization with Ethanol Injection in Symptomatic Patients with Enlarged Polycystic Kidneys. Radiology 2015, 277, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravine, D.; Gibson, R.N.; Walker, R.G.; Sheffield, L.J.; Kincaid-Smith, P.; Danks, D.M. Evaluation of ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease 1. Lancet 1994, 343, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, E.; Nutahara, K.; Okegawa, T.; Tanbo, M.; Hara, H.; Miyazaki, I.; Kobayasi, K.; Nitatori, T. Kidney volume estimations with ellipsoid equations by magnetic resonance imaging in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephron 2015, 129, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Perez, S.L.; Haus, J.M.; Sheean, P.; Patel, B.; Mar, W.; Chaudhry, V.; McKeever, L.; Braunschweig, C. Measuring Abdominal Circumference and Skeletal Muscle From a Single Cross-Sectional Computed Tomography Image: A Step-by-Step Guide for Clinicians Using National Institutes of Health Image. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2016, 40, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, Y.; Kaido, T.; Okumura, S.; Kobayashi, A.; Hammad, A.; Tamai, Y.; Inagaki, N.; Uemoto, S. Proposal for new diagnostic criteria for low skeletal muscle mass based on computed tomography imaging in Asian adults. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, F.; Couzi, L.; Le Bras, Y.; Hubrecht, R.; Dodré, E.; Geneviève, M.; Pérot, V.; Wallerand, H.; Ferrière, J.M.; Merville, P.; et al. Embolization of polycystic kidneys as an alternative to nephrectomy before renal transplantation: A pilot study. Am. J. Transplant. 2010, 10, 2363–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, A.; Cuppari, L.; Stenvinkel, P.; Lindholm, B.; Avesani, C.M. Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: What have we learned so far? J. Nephrol. 2021, 34, 1347–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chao, C.T.; Liang, P.C.; Shih, T.T.F.; Huang, J.W. Computed tomography-based sarcopenia in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis: Correlation with lean soft tissue and survival. J. Formos. Med Assoc. 2022, 121, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Song, S.H. Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: From bench to bedside. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Ho, M.C.; Kao, J.H.; Ho, C.M.; Su, T.H.; Hsu, S.J.; Huang, H.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Liang, P.C. Effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on abdominal muscle mass in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2023, 122, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, M.Z.C.; Vogt, B.P.; Reis, N.; Caramori, J.C.T. Update of the European consensus on sarcopenia: What has changed in diagnosis and prevalence in peritoneal dialysis? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1209–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Shin, Y.; Huh, J.; Sung, Y.S.; Lee, I.S.; Yoon, K.H.; Kim, K.W. Recent Issues on Body Composition Imaging for Sarcopenia Evaluation. Korean J. Radiol. 2019, 20, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasarathy, S.; Merli, M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chang, M.C.; Lyadov, V.K.; Liang, P.C.; Chen, C.M.; Shih, T.T.; Chang, Y.T. Comparing Western and Eastern criteria for sarcopenia and their association with survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Liang, P.C.; Hsu, C.H.; Chang, F.T.; Shao, Y.Y.; Ting-Fang Shih, T. Total skeletal, psoas and rectus abdominis muscle mass as prognostic factors for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Formos. Med Assoc. 2021, 120, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faron, A.; Sprinkart, A.M.; Pieper, C.C.; Kuetting, D.L.R.; Fimmers, R.; Block, W.; Meyer, C.; Thomas, D.; Attenberger, U.; Luetkens, J.A. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: Outcome prediction with MRI derived fat-free muscle area. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 125, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichet, P.L.; Taslakian, B.; Zhan, C.; Aaltonen, E.; Farquharson, S.; Hickey, R.; Horn, C.J.; Gross, J.S. MRI-Derived Sarcopenia Associated with Increased Mortality Following Yttrium-90 Radioembolization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 44, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, B.; Moore, H.; Emerson, P.; Keshaviah, P.; Prowant, B.; Nolph, K.D.; Singh, A. Lean body mass estimation by creatinine kinetics, bioimpedance, and dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Asaio J. 1995, 41, M442–M446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Li, Y.J.; Lu, X.H.; Gan, H.P.; Zuo, L.; Wang, H.Y. Correlations of lean body mass with nutritional indicators and mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakoshi, S.; Ubara, Y.; Suwabe, T.; Hiramatsu, R.; Yamanouchi, M.; Hayami, N.; Sumida, K.; Hasegawa, E.; Hoshino, J.; Sawa, N.; et al. Transcatheter renal artery embolization improves lung function in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease on hemodialysis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2012, 16, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, V.E.; Chapman, A.B.; Devuyst, O.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Perrone, R.D.; Koch, G.; Ouyang, J.; McQuade, R.D.; Blais, J.D.; Czerwiec, F.S.; et al. Tolvaptan in Later-Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1930–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazabal, M.V.; Torres, V.E.; Hogan, M.C.; Glockner, J.; King, B.F.; Ofstie, T.G.; Krasa, H.B.; Ouyang, J.; Czerwiec, F.S. Short-term effects of tolvaptan on renal function and volume in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.E.; Chebib, F.T.; Irazabal, M.V.; Ofstie, T.G.; Bungum, L.A.; Metzger, A.J.; Senum, S.R.; Hogan, M.C.; El-Zoghby, Z.M.; Kline, T.L.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Tolvaptan in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansevoort, R.T.; Arici, M.; Benzing, T.; Birn, H.; Capasso, G.; Covic, A.; Devuyst, O.; Drechsler, C.; Eckardt, K.U.; Emma, F.; et al. Recommendations for the use of tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: A position statement on behalf of the ERA-EDTA Working Groups on Inherited Kidney Disorders and European Renal Best Practice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, J.; Suwabe, T.; Hayami, N.; Sumida, K.; Mise, K.; Kawada, M.; Imafuku, A.; Hiramatsu, R.; Yamanouchi, M.; Hasegawa, E.; et al. Survival after arterial embolization therapy in patients with polycystic kidney and liver disease. J. Nephrol. 2015, 28, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characters | Total (n = 35) | Sarcopenia (n = 20) | Non-Sarcopenia (n = 15) | p-Value | Hemodialysis (n = 28) | Peritoneal Dialysis (n = 7) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 59.9 ± 9.1 | 63.2 ± 8.8 | 55.5 ± 7.6 | 0.010 * | 61.1 ± 8.5 | 54.9 ± 10.3 | 0.101 |

| Female | 19 (54.3%) | 10 (50.0%) | 9 (60.0%) | 0.557 | 14 (50.0%) | 5 (71.4%) | 0.415 |

| Body weight (kg) | 64.9 ± 14.8 | 61.0 ± 13.5 | 70.3 ± 15.1 | 0.064 | 64.8 ± 15.0 | 65.6 ± 14.8 | 0.902 |

| Body height (cm) | 163.5 ± 10.0 | 162.9 ± 11.3 | 164.4 ± 8.3 | 0.657 | 164.0 ± 10.4 | 161.7 ± 9.0 | 0.602 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.4 | 23.0 ± 2.8 | 25.9 ± 3.5 | 0.009 * | 24.0 ± 3.2 | 25.0 ± 4.3 | 0.493 |

| AC (cm) | 96.7 ± 11.0 | 94.9 ± 10.1 | 99.0 ± 12.0 | 0.281 | 97.0 ± 10.8 | 95.4 ± 12.6 | 0.746 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 0.076 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.409 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 ± 2.0 | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 11.7 ± 1.9 | 0.073 | 11.1 ± 2.1 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 0.428 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 9.0 ± 4.0 | 7.9 ± 3.3 | 10.6 ± 4.3 | 0.041 * | 7.9 ± 3.0 | 13.4 ± 4.5 | 0.001 * |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 7.0 ± 5.6 | 7.3 ± 3.0 | 6.6 ± 8.0 | 0.719 | 7.9 ± 5.9 | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 0.068 |

| Dialysis vintage (month) | 70.8 ± 62.9 | 70.9 ± 71.7 | 70.6 ± 51.2 | 0.988 | 74.8 ± 68.7 | 54.5 ± 27.5 | 0.234 |

| TKV (mL) | 4684 ± 3361 | 4847 ± 3658 | 4467 ± 3033 | 0.746 | 5005 ± 3588 | 3403 ± 1923 | 0.266 |

| PM area (cm2) | 12.6 ± 5.8 | 9.8 ± 4.2 | 16.4 ± 5.5 | <0.001 * | 12.3 ± 5.8 | 14.1 ± 6.0 | 0.446 |

| PM index (cm2/m2) | 4.66 ± 1.94 | 3.65 ± 1.50 | 6.00 ± 1.65 | <0.001 * | 4.54 ± 1.95 | 5.14 ± 1.95 | 0.467 |

| PS area (cm2) | 33.5 ± 8.8 | 32.0 ± 9.3 | 35.5 ± 7.8 | 0.246 | 33.4 ± 8.9 | 33.7 ± 8.7 | 0.932 |

| PS index (cm2/m2) | 12.26 ± 2.21 | 11.80 ± 2.29 | 12.87 ± 2.03 | 0.162 | 12.18 ± 2.23 | 12.57 ± 2.30 | 0.681 |

| Characters | Baseline (n = 35) | 3-Month Follow-Up (n = 31) | p-Value | 6-Month Follow-Up (n = 28) | p-Value | 12-Month Follow-Up (n = 24) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | 64.9 ± 14.8 | 63.2 ± 14.9 | 0.306 | 59.7 ± 13.9 | 0.178 | 61.8 ± 15.7 | 0.127 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.4 | 23.9 ± 3.4 | 0.327 | 23.3 ± 4.0 | 0.069 | 23.8 ± 3.8 | 0.260 |

| AC (cm) | 96.7 ± 11.0 | 95.3 ± 10.4 | 0.147 | 94.6 ± 12.3 | 0.095 | 93.1 ± 10.8 | 0.380 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.582 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.718 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 0.433 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 ± 2.0 | 10.8 ± 1.6 | 0.490 | 10.6 ± 1.7 | 0.693 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 0.757 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 9.0 ± 4.0 | 9.3 ± 3.4 | 0.357 | 10.2 ± 4.2 | 0.366 | 9.1 ± 3.8 | 0.999 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 7.0 ± 5.6 | 7.4 ± 6.1 | 0.170 | 6.4 ± 4.0 | 0.719 | 7.7 ± 8.7 | 0.360 |

| TKV (mL) | 4684 ± 3361 | 4079 ± 3456 | <0.001 * | 3675 ± 3401 | <0.001 * | 2459 ± 1706 | <0.001 * |

| PM area (cm2) | 12.6 ± 5.8 | 13.3 ± 5.7 | 0.002 * | 14.7 ± 6.9 | <0.001 * | 14.3 ± 7.1 | 0.001 * |

| PM index (cm2/m2) | 4.66 ± 1.94 | 4.87 ± 1.80 | 0.023 * | 5.43 ± 2.22 | <0.001 * | 5.33 ± 2.35 | 0.002 * |

| PS area (cm2) | 33.5 ± 8.8 | 32.9 ± 8.3 | 0.490 | 34.5 ± 9.7 | 0.013 * | 33.8 ± 10.3 | 0.426 |

| PS index (cm2/m2) | 12.26 ± 2.21 | 12.26 ± 2.07 | 0.745 | 12.79 ± 2.44 | 0.011 * | 12.75 ± 2.71 | 0.179 |

| Sarcopenic Group | Baseline (n = 20) | 3-Month Follow-Up (n = 19) | p-Value | 6-Month Follow-Up (n = 15) | p-Value | 12-Month Follow-Up (n = 13) | p-Value |

| AC (cm) | 94.9 ± 10.1 | 94.0 ± 10.0 | 0.325 | 90.6 ± 10.6 | 0.104 | 91.5 ± 9.8 | 0.626 |

| TKV (mL) | 4847 ± 3658 | 4079 ± 3456 | 0.001 * | 3772 ± 3661 | 0.004 * | 2368 ± 1664 | 0.001 * |

| PM area (cm2) | 9.8 ± 4.2 | 10.9 ± 4.0 | 0.015 * | 11.1 ± 4.2 | <0.001 * | 11.2 ± 5.0 | 0.001 * |

| PM index (cm2/m2) | 3.65 ± 1.50 | 4.05 ± 1.27 | 0.049 * | 4.13 ± 1.25 | <0.001 * | 4.23 ± 1.83 | 0.008 * |

| PS area (cm2) | 32.0 ± 9.3 | 32.2 ± 8.8 | 0.933 | 32.8 ± 10.1 | 0.034 * | 33.1 ± 11.0 | 0.016 * |

| PS index (cm2/m2) | 11.80 ± 2.29 | 11.95 ± 2.15 | 0.826 | 12.40 ± 2.47 | 0.027 * | 12.85 ± 2.61 | 0.009 * |

| Non-Sarcopenic Group | Baseline (n =15) | 3-Month Follow-Up (n = 12) | p-Value | 6-Month Follow-Up (n = 13) | p-Value | 12-Month Follow-Up (n = 11) | p-Value |

| AC (cm) | 99.0 ± 12.0 | 97.3 ± 11.1 | 0.310 | 98.9 ± 13.0 | 0.512 | 95.1 ± 12.0 | 0.086 |

| TKV (mL) | 4467 ± 3033 | 4080 ± 3719 | 0.051 | 3562 ± 3219 | <0.001 * | 2567 ± 1828 | 0.001 * |

| PM area (cm2) | 16.4 ± 5.5 | 17.1 ± 6.2 | 0.059 | 18.9 ± 7.3 | 0.023 * | 17.9 ± 7.8 | 0.205 |

| PM index (cm2/m2) | 6.00 ± 1.65 | 6.17 ± 1.80 | 0.275 | 6.92 ± 2.18 | 0.027 * | 6.64 ± 2.23 | 0.140 |

| PS area (cm2) | 35.5 ± 7.8 | 34.1 ± 7.6 | 0.407 | 36.5 ± 9.3 | 0.114 | 34.3 ± 9.8 | 0.259 |

| PS index (cm2/m2) | 12.87 ± 2.03 | 12.75 ± 1.91 | 0.820 | 13.23 ± 2.42 | 0.136 | 12.64 ± 2.94 | 0.574 |

| Female | Baseline (n = 19) | 3-Month Follow-Up (n = 18) | p-Value | 6-Month Follow-Up (n = 17) | p-Value | 12-Month Follow-Up (n = 16) | p-Value |

| AC (cm) | 89.7 ± 7.2 | 89.1 ± 7.5 | 0.731 | 88.1 ± 8.8 | 0.369 | 87.3 ± 7.6 | 0.265 |

| TKV (mL) | 3202 ± 1635 | 2656 ± 1449 | 0.001 * | 2244 ± 1220 | <0.001 * | 1916 ± 1197 | <0.001 * |

| PM area (cm2) | 9.5 ± 3.7 | 10.3 ± 3.3 | 0.004 * | 10.9 ± 3.6 | 0.002 * | 10.6 ± 3.2 | 0.024 * |

| PM index (cm2/m2) | 3.79 ± 1.44 | 4.11 ± 1.18 | 0.055 | 4.35 ± 1.27 | 0.015 * | 4.31 ± 1.35 | 0.034 * |

| PS area (cm2) | 28.6 ± 6.2 | 27.8 ± 4.4 | 0.640 | 29.4 ± 6.5 | 0.098 | 29.0 ± 6.5 | 0.509 |

| PS index (cm2/m2) | 11.47 ± 2.14 | 11.39 ± 1.65 | 0.816 | 11.88 ± 2.23 | 0.056 | 11.88 ± 2.45 | 0.263 |

| Male | Baseline (n =16) | 3-Month Follow-Up (n = 13) | p-Value | 6-Month Follow-Up (n = 11) | p-Value | 12-Month Follow-Up (n = 8) | p-Value |

| AC (cm) | 104.9 ± 8.8 | 103.9 ± 7.2 | 0.106 | 104.0 ± 10.7 | 0.104 | 104.8 ± 5.1 | 0.958 |

| TKV (mL) | 6445 ± 4039 | 6048 ± 4433 | 0.016 * | 5886 ± 4471 | 0.007 * | 3545 ± 2113 | 0.007 * |

| PM area (cm2) | 16.4 ± 5.6 | 17.5 ± 5.8 | 0.077 | 20.6 ± 6.8 | 0.005 * | 21.6 ± 7.2 | 0.016 * |

| PM index (cm2/m2) | 5.69 ± 1.99 | 5.92 ± 2.02 | 0.219 | 7.09 ± 2.39 | 0.008 * | 7.38 ± 2.67 | 0.038 * |

| PS area (cm2) | 39.3 ± 7.9 | 39.9 ± 7.3 | 0.629 | 42.6 ± 8.4 | 0.070 | 43.3 ± 10.0 | 0.682 |

| PS index (cm2/m2) | 13.19 ± 1.97 | 13.46 ± 2.03 | 0.829 | 14.18 ± 2.14 | 0.111 | 14.50 ± 2.45 | 0.504 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-M.; Lai, T.-S.; Liao, T.-W.; Trianingsih; Wu, Y.-H.; Cheng, C.-J.; Wu, C.-H. Efficacy of Transcatheter Renal Arterial Embolization to Contract Renal Size and Increase Muscle Mass in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020302

Lin C-M, Lai T-S, Liao T-W, Trianingsih, Wu Y-H, Cheng C-J, Wu C-H. Efficacy of Transcatheter Renal Arterial Embolization to Contract Renal Size and Increase Muscle Mass in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020302

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Che-Ming, Tai-Shuan Lai, Ting-Wei Liao, Trianingsih, Ying-Hui Wu, Chun-Jung Cheng, and Chih-Horng Wu. 2026. "Efficacy of Transcatheter Renal Arterial Embolization to Contract Renal Size and Increase Muscle Mass in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020302

APA StyleLin, C.-M., Lai, T.-S., Liao, T.-W., Trianingsih, Wu, Y.-H., Cheng, C.-J., & Wu, C.-H. (2026). Efficacy of Transcatheter Renal Arterial Embolization to Contract Renal Size and Increase Muscle Mass in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics, 16(2), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020302