Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD)-Associated Ocular Pathology—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

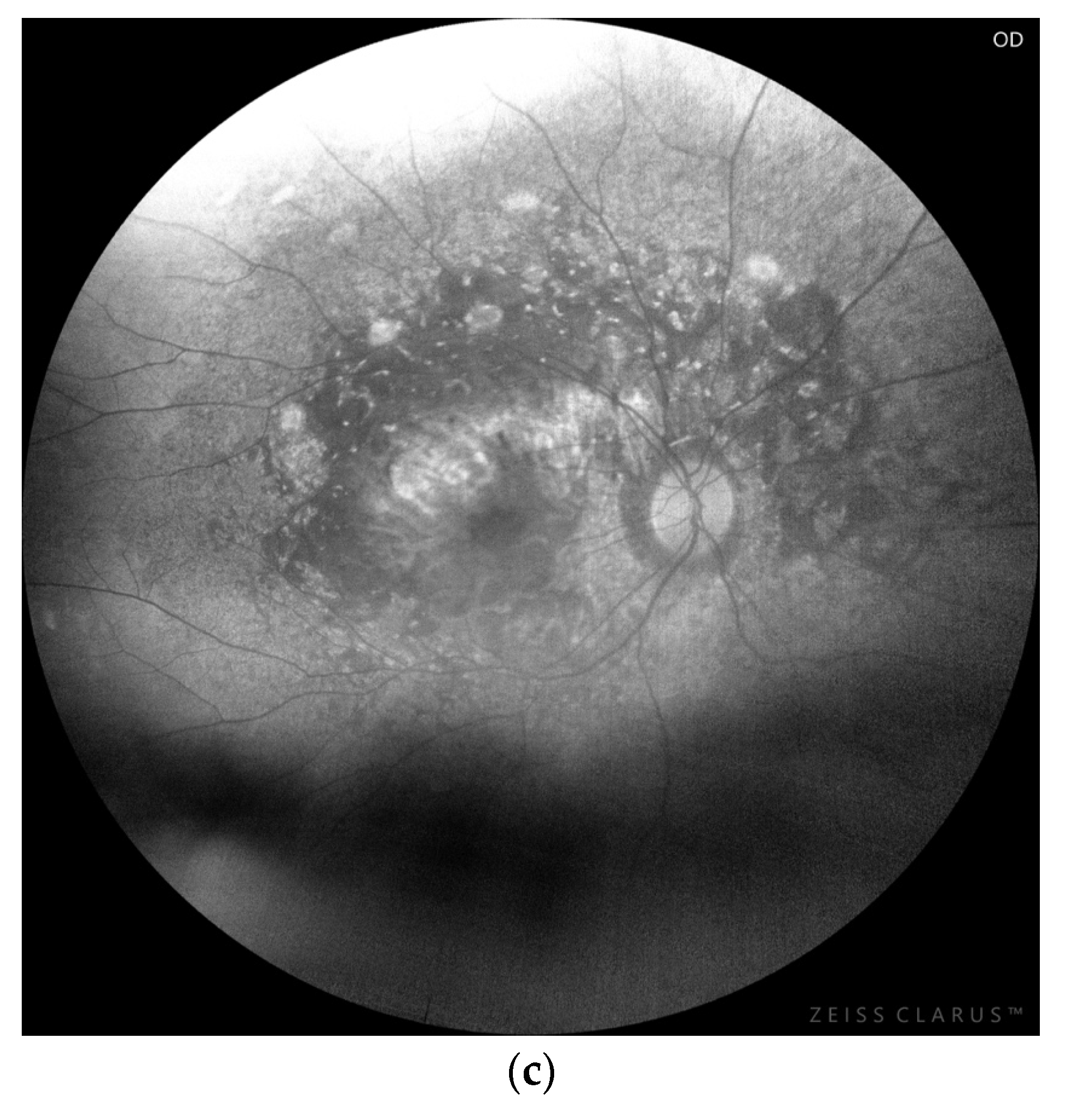

3.1. Chorioretinopathy

3.2. Myopia

3.3. MNV

3.4. Other Ocular Findings

3.5. Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Biase, I.; Viau, K.S.; Liu, A.; Yuzyuk, T.; Botto, L.D.; Pasquali, M.; Longo, N. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Clinical Outcome of Patients with Mitochondrial Trifunctional Protein/Long-Chain 3-Hydroxy Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. JIMD Rep. 2017, 31, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tyni, T.; Pihko, H. Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Acta Paediatr. 1999, 88, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyni, T.; Paetau, A.; Strauss, A.W.; Middleton, B.; Kivelä, T. Mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation in the human eye and brain: Implications for the retinopathy of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr. Res. 2004, 56, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Choi, D.; Gregor, A.; Sim, E.; Lau, A.; Black, D.; Scanga, H.L.; Linshinski, A.; Pennesi, M.E.; Sahel, J.A.; et al. Plasma Metabolomics, Lipidomics, and Acylcarnitines Are Associated With Vision and Genotype but Not With Dietary Intake in Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD). J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2025, 48, e70060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Piekutowska-Abramczuk, D.; Olsen, R.K.; Wierzba, J.; Popowska, E.; Jurkiewicz, D.; Ciara, E.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Gradowska, W.; Sykut-Cegielska, J.; Krajewska-Walasek, M.; et al. A comprehensive HADHA c.1528G>C frequency study reveals high prevalence of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in Poland. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010, 33, S373–S377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillingham, M.B.; Choi, D.; Gregor, A.; Wongchaisuwat, N.; Black, D.; Scanga, H.L.; Nischal, K.K.; Sahel, J.A.; Arnold, G.; Vockley, J.; et al. Early diagnosis and treatment by newborn screening (NBS) or family history is associated with improved visual outcomes for long-chain 3-hydroxyacylCoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD) chorioretinopathy. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2024, 47, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Polinati, P.P.; Ilmarinen, T.; Trokovic, R.; Hyotylainen, T.; Otonkoski, T.; Suomalainen, A.; Skottman, H.; Tyni, T. Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived RPE Cells: Understanding the Pathogenesis of Retinopathy in Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 3371–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babcock, S.J.; Curtis, A.G.; Gaston, G.; Elizondo, G.; Gillingham, M.B.; Ryals, R.C. The LCHADD Mouse Model Recapitulates Early-Stage Chorioretinopathy in LCHADD Patients. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prasun, P.; LoPiccolo, M.K.; Ginevic, I. Long-Chain Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency/Trifunctional Protein Deficiency. In GeneReviews® [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nedoszytko, B.; Siemińska, A.; Strapagiel, D.; Dąbrowski, S.; Słomka, M.; Sobalska-Kwapis, M.; Marciniak, B.; Wierzba, J.; Skokowski, J.; Fijałkowski, M.; et al. High prevalence of carriers of variant c.1528G>C of HADHA gene causing long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD) in the population of adult Kashubians from North Poland. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dessein, A.F.; Hebbar, E.; Vamecq, J.; Lebredonchel, E.; Devos, A.; Ghoumid, J.; Mention, K.; Dobbelaere, D.; Chevalier-Curt, M.J.; Fontaine, M.; et al. A novel HADHA variant associated with an atypical moderate and late-onset LCHAD deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2022, 31, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fahnehjelm, K.T.; Liu, Y.; Olsson, D.; Amrén, U.; Haglind, C.B.; Holmström, G.; Halldin, M.; Andreasson, S.; Nordenström, A. Most patients with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency develop pathological or subnormal retinal function. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Boer, M.E.; Wanders, R.J.; Morris, A.A.; IJlst, L.; Heymans, H.S.; Wijburg, F.A. Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: Clinical presentation and follow-up of 50 patients. Pediatrics 2002, 109, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, A.L.; Pennesi, M.E.; Harding, C.O.; Weleber, R.G.; Gillingham, M.B. Observations regarding retinopathy in mitochondrial trifunctional protein deficiencies. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 106, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gregor, A.N.; Black, D.; Wongchaisuwat, N.; Pennesi, M.E.; Gillingham, M.B. Patient-reported visual function outcomes agree with visual acuity and ophthalmologist-graded scoring of visual function among patients with long-chain 3-hydroxyacylcoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD). Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2024, 41, 101171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gillingham, M.B.; Weleber, R.G.; Neuringer, M.; Connor, W.E.; Mills, M.; van Calcar, S.; Ver Hoeve, J.; Wolff, J.; Harding, C.O. Effect of optimal dietary therapy upon visual function in children with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase and trifunctional protein deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005, 86, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gillingham, M.B.; Connor, W.E.; Matern, D.; Rinaldo, P.; Burlingame, T.; Meeuws, K.; Harding, C.O. Optimal dietary therapy of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003, 79, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rücklová, K.; Hrubá, E.; Pavlíková, M.; Hanák, P.; Farolfi, M.; Chrastina, P.; Vlášková, H.; Kousal, B.; Smolka, V.; Foltenová, H.; et al. Impact of Newborn Screening and Early Dietary Management on Clinical Outcome of Patients with Long Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency and Medium Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency-A Retrospective Nationwide Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sykut-Cegielska, J.; Gradowska, W.; Piekutowska-Abramczuk, D.; Andresen, B.S.; Olsen, R.K.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Pronicki, M.; Pajdowska, M.; Bogdańska, A.; Jabłońska, E.; et al. Urgent metabolic service improves survival in long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency detected by symptomatic identification and pilot newborn screening. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahnehjelm, K.T.; Holmström, G.; Ying, L.; Haglind, C.B.; Nordenström, A.; Halldin, M.; Alm, J.; Nemeth, A.; von Döbeln, U. Ocular characteristics in 10 children with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: A cross-sectional study with long-term follow-up. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008, 86, 329–337, Erratum in Acta Ophthalmol. 2008, 86, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boese, E.A.; Jain, N.; Jia, Y.; Schlechter, C.L.; Harding, C.O.; Gao, S.S.; Patel, R.C.; Huang, D.; Weleber, R.G.; Gillingham, M.B.; et al. Characterization of Chorioretinopathy Associated with Mitochondrial Trifunctional Protein Disorders: Long-Term Follow-up of 21 Cases. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dulz, S.; Atiskova, Y.; Engel, P.; Wildner, J.; Tsiakas, K.; Santer, R. Retained visual function in a subset of patients with long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD). Ophthalmic Genet. 2021, 42, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongchaisuwat, N.; Gillingham, M.B.; Yang, P.; Everett, L.; Gregor, A.; Harding, C.O.; Sahel, J.A.; Nischal, K.K.; Scanga, H.L.; Black, D.; et al. A proposal for an updated staging system for LCHADD retinopathy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2024, 45, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, M.; Gawęcki, M. Long-term follow-up of eight patients with long chain 3-hydroxy-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Acta Ophthalmol. 2025, 103, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongchaisuwat, N.; Wang, J.; Yang, P.; Everett, L.; Gregor, A.; Sahel, J.A.; Nischal, K.K.; Pennesi, M.E.; Gillingham, M.B.; Jia, Y. Optical coherence tomography angiography of choroidal neovascularization in long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD). Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2023, 32, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hubert, M.; Gawęcki, M.; Grzybowski, A. Macular Neovascularization in Pediatric Patients with Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency: A Retrospective Analysis of a Case Series. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pons, R.; Roig, M.; Riudor, E.; Ribes, A.; Briones, P.; Ortigosa, L.; Baldellou, A.; Gil-Gibernau, J.; Olesti, M.; Navarro, C.; et al. The clinical spectrum of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr. Neurol. 1996, 14, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertini, E.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Garavaglia, B.; Burlina, A.B.; Sabatelli, M.; Rimoldi, M.; Bartuli, A.; Sabetta, G.; DiDonato, S. Peripheral sensory-motor polyneuropathy, pigmentary retinopathy, and fatal cardiomyopathy in long-chain 3-hydroxy-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1992, 151, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyni, T.; Kivelä, T.; Lappi, M.; Summanen, P.; Nikoskelainen, E.; Pihko, H. Ophthalmologic findings in long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency caused by the G1528C mutation: A new type of hereditary metabolic chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 1998, 105, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyni, T.; Immonen, T.; Lindahl, P.; Majander, A.; Kivelä, T. Refined staging for chorioretinopathy in long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Ophthalmic Res. 2012, 48, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonekawa, Y.; Thomas, B.J.; Capone, A., Jr. Ultra-Wide-Field Autofluorescence in Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency Chorioretinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, e155033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrigo, A.; Aragona, E.; Battaglia, O.; Saladino, A.; Amato, A.; Borghesan, F.; Pina, A.; Calcagno, F.; Hassan Farah, R.; Bandello, F.; et al. Outer retinal tubulation formation and clinical course of advanced age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Hormel, T.T.; Wang, J.; Choi, D.; Pennesi, M.E.; Gillingham, M.B.; Jia, Y. Characterizing Long-Chain 3-Hydroxy-Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD) Chorioretinopathy Using OCT and OCTA. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sacconi, R.; Bandello, F.; Querques, G. Choroidal Neovascularization Associated with Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2022, 16, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Jonas, R.A.; Bikbov, M.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Panda-Jonas, S. Myopia: Histology, clinical features, and potential implications for the etiology of axial elongation. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2023, 96, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Xia, H.; Ren, X.; Hou, Q.; Ge, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, X. Choroidal Morphologic and Vascular Features in Patients With Myopic Choroidal Neovascularization and Different Levels of Myopia Based on Image Binarization of Optical Coherence Tomography. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 791012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maines, E.; Gugelmo, G.; Vitturi, N.; Dianin, A.; Rubert, L.; Piccoli, G.; Soffiati, M.; Cauvin, V.; Franceschi, R. A Focus on the Role of Dietary Treatment in the Prevention of Retinal Dysfunction in Patients with Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kivelä, T.T. Early dietary therapy for long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency can maintain vision despite subnormal retinal function. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillingham, M.B.; Heitner, S.B.; Martin, J.; Rose, S.; Goldstein, A.; El-Gharbawy, A.H.; Deward, S.; Lasarev, M.R.; Pollaro, J.; DeLany, J.P.; et al. Triheptanoin versus trioctanoin for long-chain fatty acid oxidation disorders: A double blinded, randomized controlled trial. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017, 40, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MacDonald, A.; Webster, R.; Whitlock, M.; Gerrard, A.; Daly, A.; Preece, M.A.; Evans, S.; Ashmore, C.; Chakrapani, A.; Vijay, S.; et al. The safety of Lipistart, a medium-chain triglyceride based formula, in the dietary treatment of long-chain fatty acid disorders: A phase I study. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 31, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozrzymas, R.; Konikowska, K.; Regulska-Ilow, B. Energy exchangers with LCT as a precision method for diet control in LCHADD. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Study Design | No of Patients | Population | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kristina T. Fahnehjelm et al., 2008 [20] |

| 10 patients |

|

|

| Kristina T. Fahnehjelm et al., 2016 [12] |

| 12 patients |

|

|

| Erin A. Boese et al., 2016 [21] |

| 18 patients with LCHADD (including 3 with TFPD) |

|

|

| Simon Dulz et al., 2021 [22] |

| 6 patients |

|

|

| Kristina Rücklová et al., 2021 [18] |

| 28 patients with LCHADD and TFPD |

|

|

| Melanie B. Gillingham et al., 2024 [6] |

| 37 LCHADD patients + 3 TFPD patients |

|

|

| Nida Wongchaisuwat et al., 2024 [23] |

| 37 LCHADD patients + 3 TFPD patients |

|

|

| Magdalena Hubert et al., 2025 [24] |

| 8 patients |

|

|

| Study | Study Design | No of Patients | Population | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nida Wongchaisuwat et al., 2023 [25] |

|

|

|

|

| Magdalena Hubert et al., 2025 [26] |

|

|

|

|

| Study | Study Design | No of Patients | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanie B. Gillingham et al., 2005 [16] |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hubert, M.; Gawęcki, M. Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD)-Associated Ocular Pathology—A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020295

Hubert M, Gawęcki M. Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD)-Associated Ocular Pathology—A Narrative Review. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020295

Chicago/Turabian StyleHubert, Magdalena, and Maciej Gawęcki. 2026. "Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD)-Associated Ocular Pathology—A Narrative Review" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020295

APA StyleHubert, M., & Gawęcki, M. (2026). Long-Chain 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (LCHADD)-Associated Ocular Pathology—A Narrative Review. Diagnostics, 16(2), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020295