Translating Molecular Subtypes into Cost-Effective Radiogenomic Biomarkers for Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.2. In-House RNA-Seq and CT Cohort

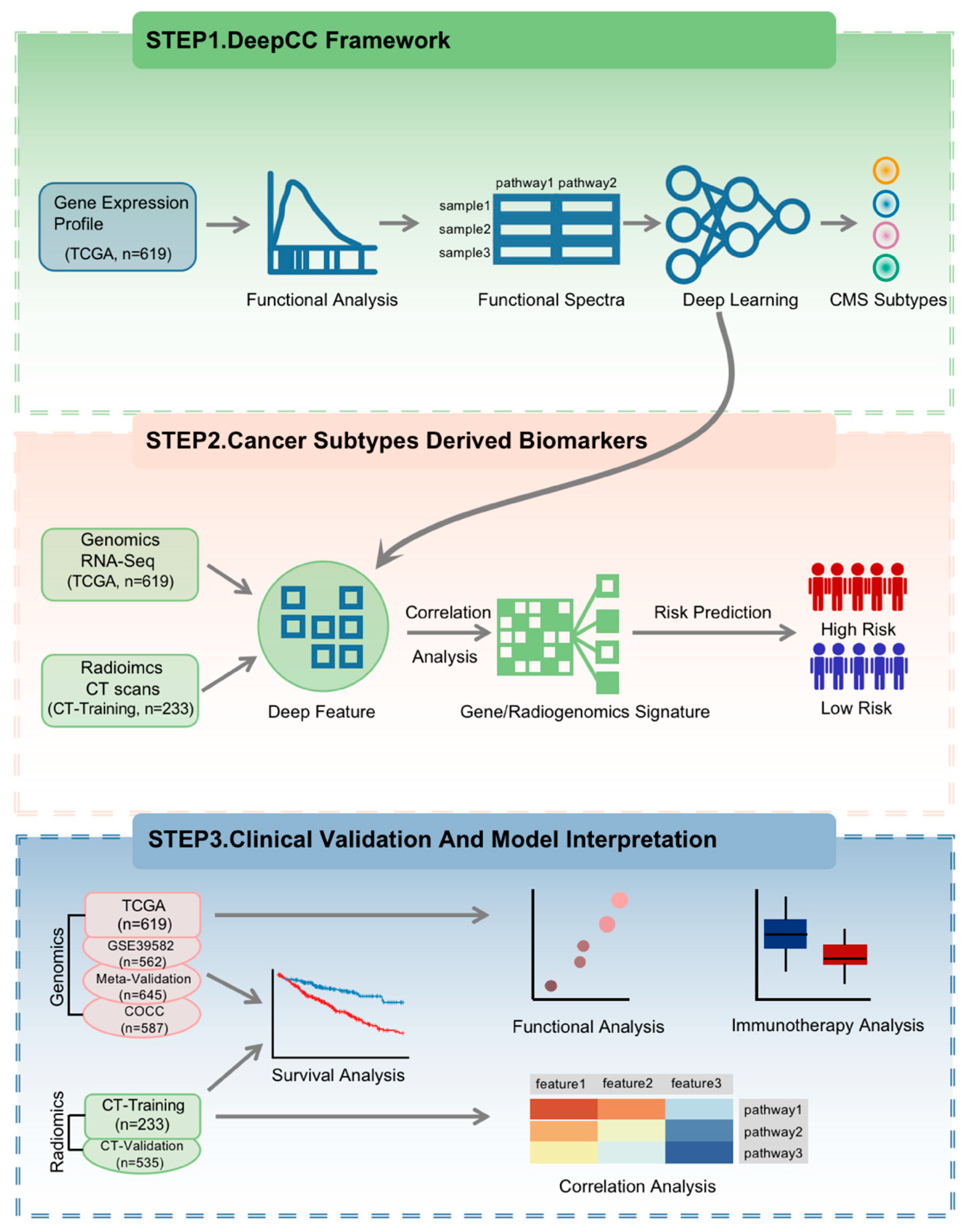

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Functional Analysis

2.5. Immunotherapy Analysis

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

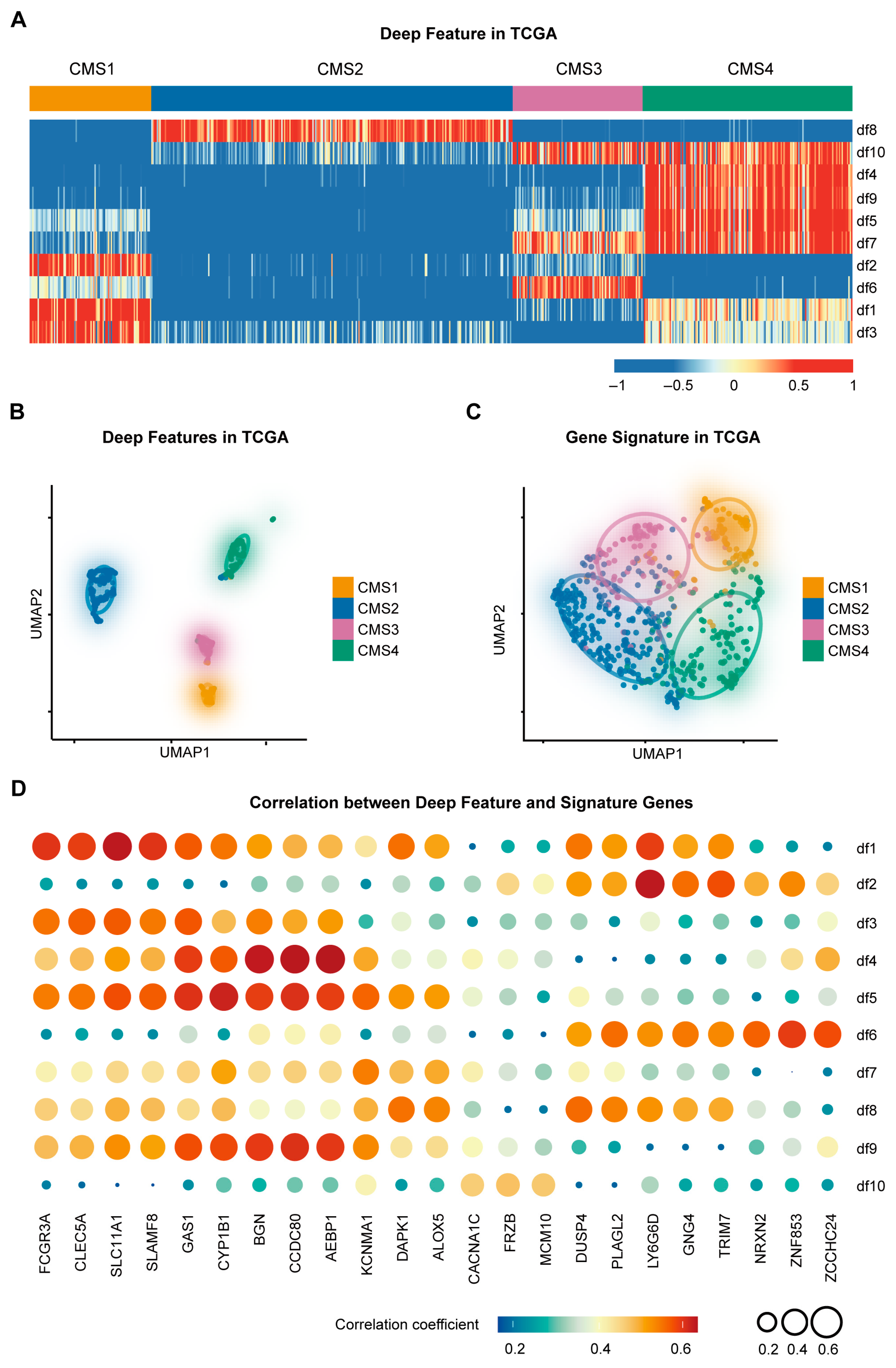

3.1. Construction of the CMS-Associated Gene Signature

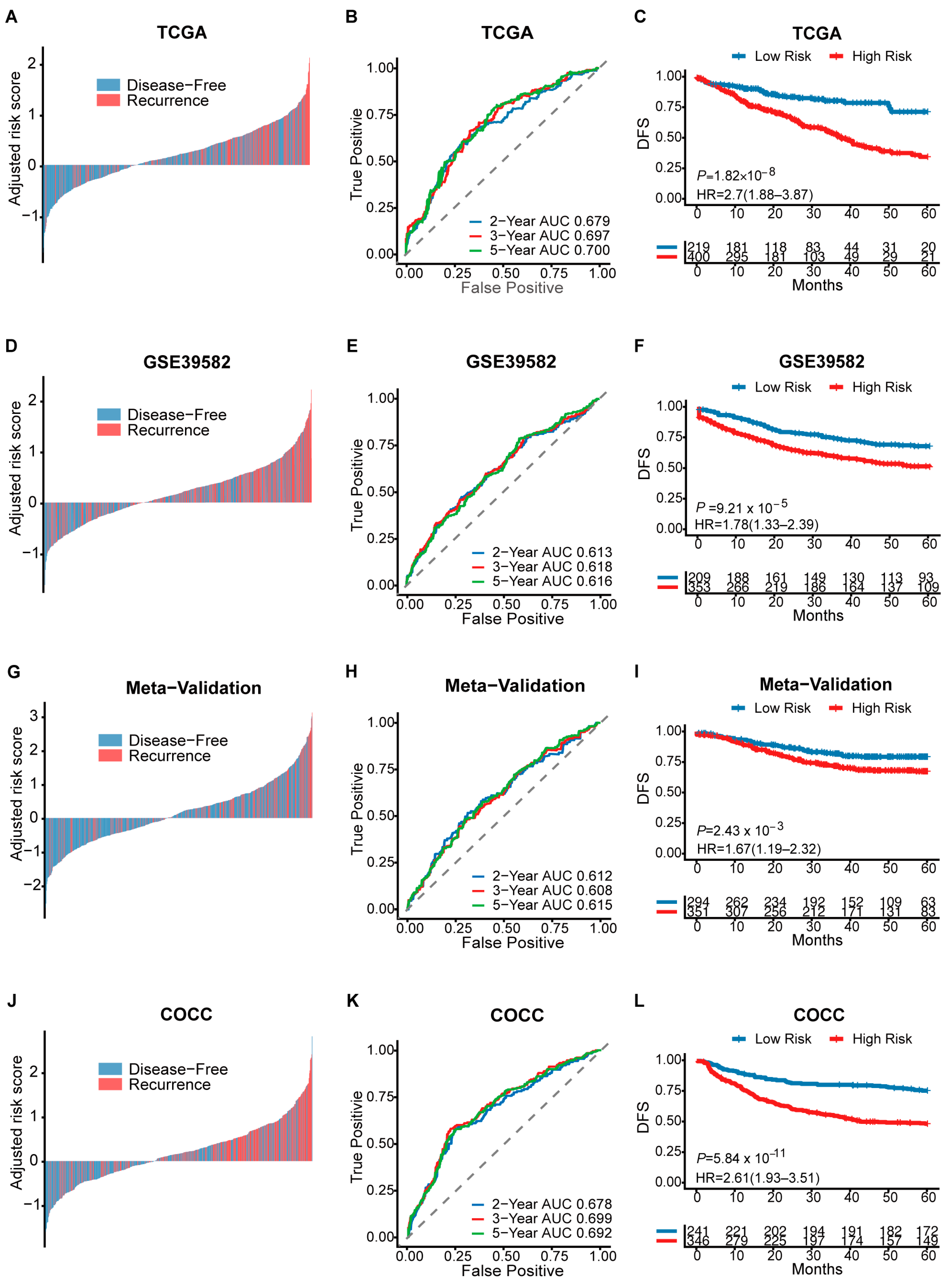

3.2. Prognosis Assessment of CMS-Associated Gene Signature

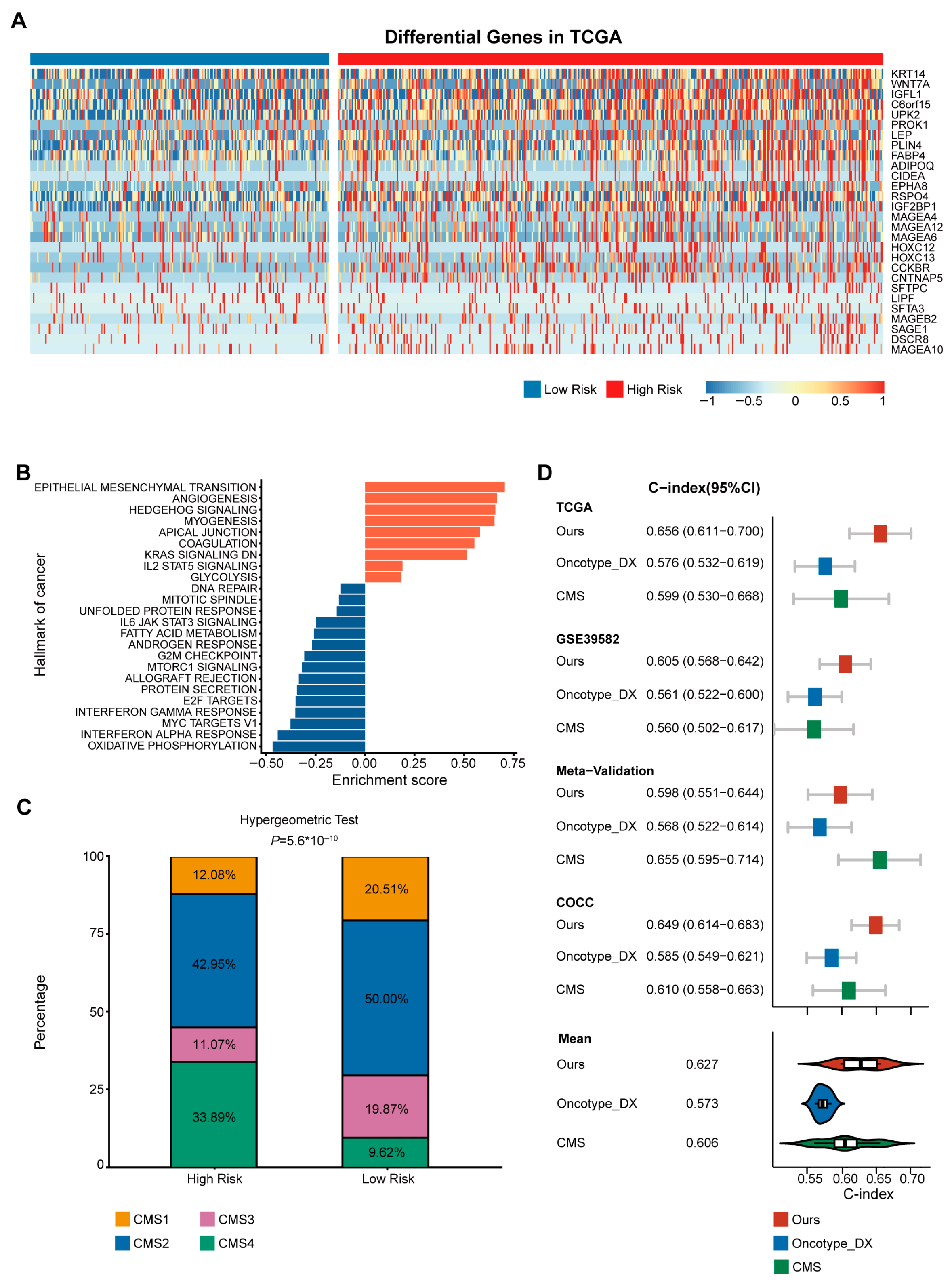

3.3. High-Risk Group Was Associated with CMS4

3.4. Superior Prognostic Predictive Performance of CMS-Associated Gene Signature Compared to Oncotype DX and CMS

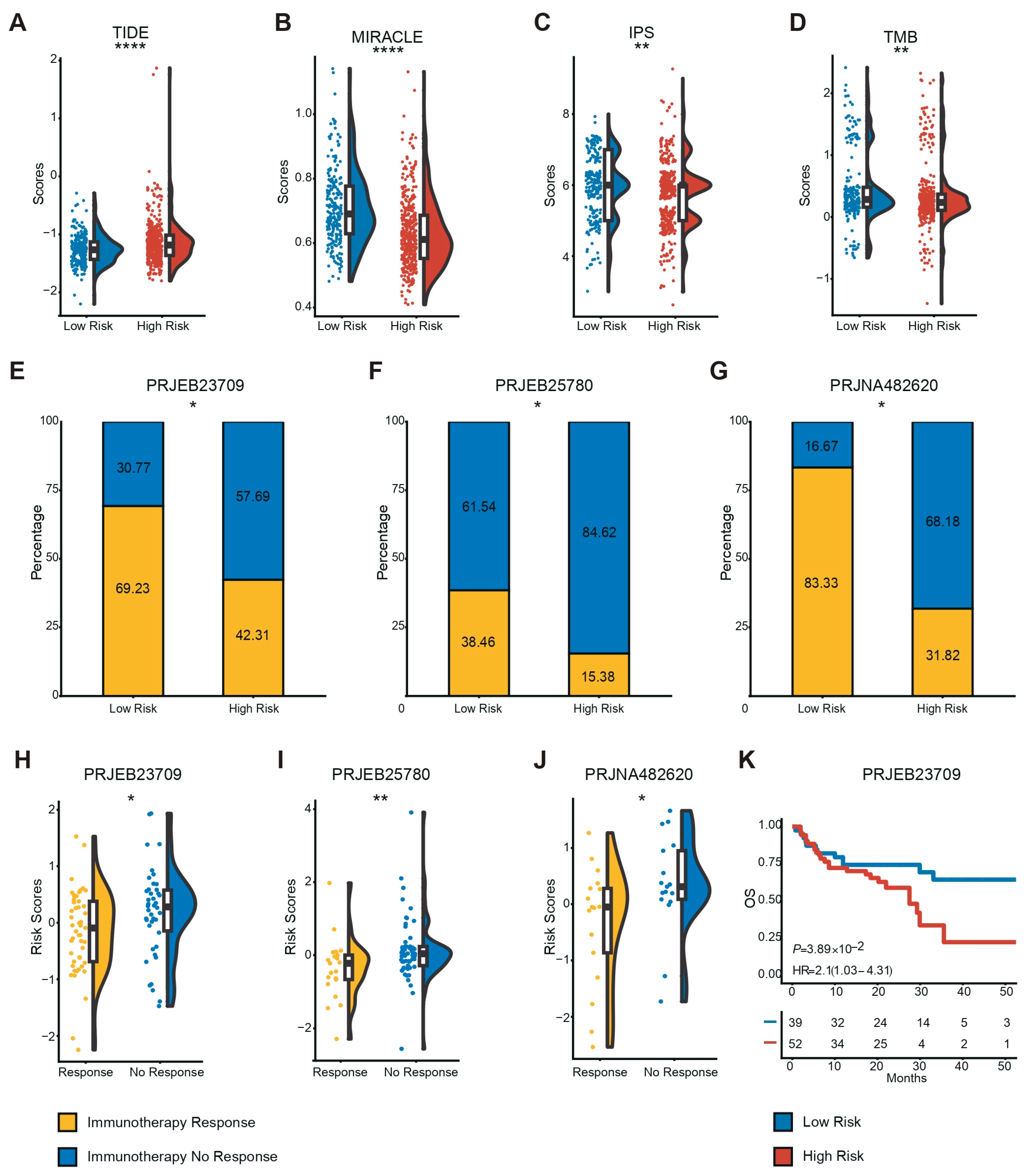

3.5. Low-Risk Patients More Likely to Benefit from Immunotherapy

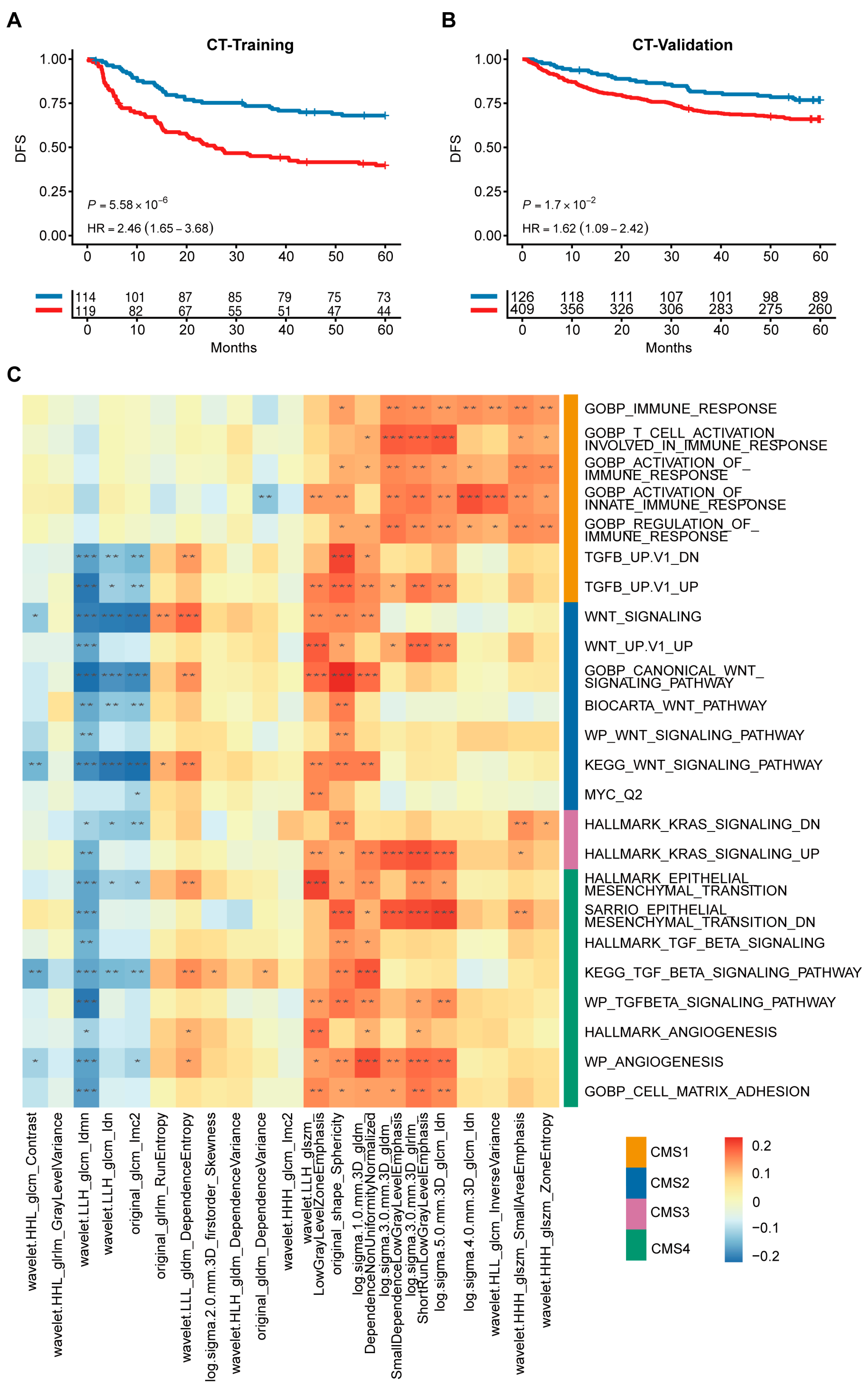

3.6. Radiogenomic Signature Predicts Patient Prognosis and Correlates with CMS Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CRCSC | Colorectal Cancer Subtyping Consortium |

| CMS | Consensus molecular subtypes |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| COCC | Clinical Genomic Study of Colorectal Cancer in China |

| ICGC-ARGO | International Cancer Genome Consortium to Accelerate Research in Genomic Oncology |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| ssGSEA | single-sample gene set enrichment analysis |

| TIGER | Tumor Immunotherapy Gene Expression Resource |

| UMAP | Uniform manifold approximation and projection |

| RS | Risk score |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoul, R.; Alva, S.; Wilkins, K.B. Surveillance and Survivorship after Treatment for Colon Cancer. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2015, 28, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyot, F.; Faivre, J.; Manfredi, S.; Meny, B.; Bonithon-Kopp, C.; Bouvier, A.M. Time trends in the treatment and survival of recurrences from colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusyk, A.; Almendro, V.; Polyak, K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: A looking glass for cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirke, P.; Williams, G.T.; Ectors, N.; Ensari, A.; Piard, F.; Nagtegaal, I. The future of the TNM staging system in colorectal cancer: Time for a debate? Lancet Oncol. 2007, 8, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligmann, J.F. Colorectal cancer staging—Time for a re-think on TNM? BJS 2025, 112, znaf047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Quezada, S.A.; Larkin, J.; Swanton, C. Translational implications of tumor heterogeneity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Sung, J.S.; Chung, H.J.; Lim, A.R.; Kim, J.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, K.H.; Kim, Y.H. Clinical Application of Targeted Deep Sequencing in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: Actionable Genomic Alteration in K-MASTER Project. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, E.; Eason, K.; Cervantes, A.; Salazar, R.; Sadanandam, A. Context matters-consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer as biomarkers for clinical trials. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; de Reynies, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Hofree, M.; Lin, K.; Maru, D.; Kopetz, S.; Shen, J.P. Implications of Intratumor Heterogeneity on Consensus Molecular Subtype (CMS) in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, D.G.; Davis, J.S.; Broom, B.M.; Overman, M.J.; Morris, J.; Kopetz, S. Back to the Colorectal Cancer Consensus Molecular Subtype Future. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, R.V.; Schmeier, S.; Lau, Y.C.; Pearson, J.F.; Frizelle, F.A. Molecular subtyping improves prognostication of Stage 2 colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; You, C.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Su, G.H.; Xia, B.Q.; Zheng, R.C.; Zhang, D.D.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Gu, Y.J.; et al. Radiogenomic analysis reveals tumor heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, X.; Zou, Y.; Yan, K.; Zheng, H.; Liang, D.; Li, Z.C. Biologic Pathways Underlying Prognostic Radiomics Phenotypes from Paired MRI and RNA Sequencing in Glioblastoma. Radiology 2021, 301, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirienko, M.; Sollini, M.; Corbetta, M.; Voulaz, E.; Gozzi, N.; Interlenghi, M.; Gallivanone, F.; Castiglioni, I.; Asselta, R.; Duga, S.; et al. Radiomics and gene expression profile to characterise the disease and predict outcome in patients with lung cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 3643–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayakumar, D.; Zhang, Z.; Xi, Y.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Fulkerson, M.; Haldeman, S.; McKenzie, T.; Yousuf, Q.; Joyce, A.; Hajibeigi, A.; et al. Deciphering Intratumoral Molecular Heterogeneity in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma with a Radiogenomics Platform. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4794–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Ye, F.; Han, F.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J. A radiogenomics biomarker based on immunological heterogeneity for non-invasive prognosis of renal clear cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 956679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Luo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ma, X. Integrative radiogenomics analysis for predicting molecular features and survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging 2021, 13, 9960–9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, N.F.; Aberle, D.R.; Hsu, W. Using deep neural networks and interpretability methods to identify gene expression patterns that predict radiomic features and histology in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Med. Imaging 2021, 8, 031906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marisa, L.; de Reynies, A.; Duval, A.; Selves, J.; Gaub, M.P.; Vescovo, L.; Etienne-Grimaldi, M.C.; Schiappa, R.; Guenot, D.; Ayadi, M.; et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: Characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A.; Cai, C.; Langfelder, P.; Geschwind, D.H.; Kurian, S.M.; Salomon, D.R.; Horvath, S. Strategies for aggregating gene expression data: The collapseRows R function. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leek, J.T.; Johnson, W.E.; Parker, H.S.; Jaffe, A.E.; Storey, J.D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 882–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wang, W.; Tan, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fessler, E.; Vermeulen, L.; Wang, X. DeepCC: A novel deep learning-based framework for cancer molecular subtype classification. Oncogenesis 2019, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoentong, P.; Finotello, F.; Angelova, M.; Mayer, C.; Efremova, M.; Rieder, D.; Hackl, H.; Trajanoski, Z. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic Analyses Reveal Genotype-Immunophenotype Relationships and Predictors of Response to Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbie, D.A.; Tamayo, P.; Boehm, J.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Moody, S.E.; Dunn, I.F.; Schinzel, A.C.; Sandy, P.; Meylan, E.; Scholl, C.; et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature 2009, 462, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Gu, S.; Pan, D.; Fu, J.; Sahu, A.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Traugh, N.; Bu, X.; Li, B.; et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Ye, Z.; Shen, R.; Yu, G.; Wu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, R.; Qiu, W.; Huang, N.; Sun, L.; et al. IOBR: Multi-Omics Immuno-Oncology Biological Research to Decode Tumor Microenvironment and Signatures. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 687975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, T.; Kongpachith, S.; Halliwill, K.; Roelands, J.; Hendrickx, W.; Marincola, F.M.; Hudson, T.J.; Jacob, H.J.; Bedognetti, D.; Samayoa, J.; et al. A balance score between immune stimulatory and suppressive microenvironments identifies mediators of tumour immunity and predicts pan-cancer survival. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; Xu, L.; Yi, M.; Yu, S.; Wu, K.; Luo, S. Novel immune checkpoint targets: Moving beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, P.; Ren, J.; et al. TIGER: A Web Portal of Tumor Immunotherapy Gene Expression Resource. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 21, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quasar Collaborative, G.; Gray, R.; Barnwell, J.; McConkey, C.; Hills, R.K.; Williams, N.S.; Kerr, D.J. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: A randomised study. Lancet 2007, 370, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Huang, X.; Feng, Y.; Wei, C.; Liu, H.; Ru, H.; Qin, H.; Lai, H.; Wu, G.; Xie, W.; et al. Immune infiltration and immune gene signature predict the response to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1832347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekervel, J.; Hompes, D.; van Malenstein, H.; Popovic, D.; Sagaert, X.; De Moor, B.; Van Cutsem, E.; D’Hoore, A.; Verslype, C.; van Pelt, J. Hypoxia-driven gene expression is an independent prognostic factor in stage II and III colon cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Fan, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, E.; Li, P.; Zhou, W.; Peng, J.; Li, L. Molecular subtype identification and prognosis stratification by a metabolism-related gene expression signature in colorectal cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.M.; Chen, J.Z.; Sui, H.M.; Si-Ma, X.Q.; Li, G.Q.; Liu, C.; Li, J.L.; Ding, Y.Q.; Li, J.M. A five-gene signature as a potential predictor of metastasis and survival in colorectal cancer. J. Pathol. 2010, 220, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharib, E.; Nasrinasrabadi, P.; Zali, M.R. Development and validation of a lipogenic genes panel for diagnosis and recurrence of colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Hoorn, S.; de Back, T.R.; Sommeijer, D.W.; Vermeulen, L. Clinical Value of Consensus Molecular Subtypes in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becht, E.; de Reynies, A.; Giraldo, N.A.; Pilati, C.; Buttard, B.; Lacroix, L.; Selves, J.; Sautes-Fridman, C.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Fridman, W.H. Immune and Stromal Classification of Colorectal Cancer Is Associated with Molecular Subtypes and Relevant for Precision Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4057–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| b | TCGA (n = 619) | GSE39582 (n = 562) | Meta-Validation (n = 645) | COCC (n = 587) | Training (n = 233) | Validation (n = 535) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| <65 years old | 249 (40.2%) | 211 (37.5%) | 275 (42.6%) | 388 (66.1%) | 166 (71.2%) | 208 (38.9%) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 years old | 370 (59.8%) | 350 (62.3%) | 370 (57.4%) | 192 (32.7%) | 66 (28.3%) | 132 (24.7%) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 329 (53.2%) | 309 (55.0%) | 333 (51.6%) | 342 (58.3%) | 133 (57.1%) | 312 (58.3%) | 0.107 |

| Female | 290 (46.8%) | 253 (45.0%) | 312 (48.4%) | 245 (41.7%) | 100 (42.9%) | 223 (41.7%) | |

| TNM Stage | |||||||

| I | 105 (17.0%) | 32 (5.7%) | 69 (10.7%) | 67 (11.4%) | 22 (9.4%) | 82 (15.3%) | <0.001 |

| II | 228 (36.8%) | 262 (46.6%) | 326 (50.5%) | 201 (34.2%) | 65 (27.9%) | 186 (34.8%) | |

| III | 179 (28.9%) | 204 (36.3%) | 223 (34.6%) | 152 (25.9%) | 64 (27.5%) | 189 (35.3%) | |

| IV | 88 (14.2%) | 60 (10.7%) | 27 (4.2%) | 160 (27.3%) | 79 (33.9%) | 78 (14.6%) | |

| T Stage | |||||||

| T1 | 21 (3.4%) | 12 (2.1%) | - | 23 (3.9%) | 7 (3.0%) | 26 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| T2 | 105 (17.0%) | 44 (7.8%) | - | 60 (10.2%) | 19 (8.2%) | 70 (13.1%) | |

| T3 | 422 (68.2%) | 364 (64.8%) | 82 (12.7%) | 400 (68.1%) | 167 (71.7%) | 373 (69.7%) | |

| T4 | 70 (11.3%) | 119 (21.2%) | 7 (1.1%) | 92 (15.7%) | 37 (15.9%) | 65 (12.1%) | |

| N Stage | |||||||

| N0 | 351 (56.7%) | 299 (53.2%) | 89 (13.8%) | 294 (50.1%) | 105 (45.1%) | 284 (53.1%) | <0.001 |

| N1 | 150 (24.2%) | 133 (23.7%) | - | 191 (32.5%) | 79 (33.9%) | 176 (32.9%) | |

| N2 | 115 (18.6%) | 98 (17.4%) | - | 97 (16.5%) | 49 (21.0%) | 71 (13.3%) | |

| M Stage | |||||||

| M0 | 459 (74.2) | 479 (85.2) | 89 (13.8) | 422 (71.9) | 154 (66.1) | 457 (85.4%) | <0.001 |

| M1 | 87 (14.1) | 61 (10.9) | 0 (0.0) | 118 (20.1) | 59 (25.3) | 77 (14.4%) | |

| MSS/MSI Status | |||||||

| MSI | 188 (30.4%) | 72 (12.8%) | 33 (5.1%) | 53 (9.0%) | 13 (5.6%) | 85 (15.9%) | <0.001 |

| MSS | 428 (69.1%) | 444 (79.0%) | 95 (14.7%) | 496 (84.5%) | 207 (88.8%) | 264 (49.3%) | |

| CMS Stage | |||||||

| CMS1 | 68 (11.0%) | 89 (15.8%) | 130 (20.2%) | 73 (12.4%) | 16 (6.9%) | - | <0.001 |

| CMS2 | 206 (33.3%) | 232 (41.3%) | 237 (36.7%) | 233 (39.7%) | 73 (31.3%) | - | |

| CMS3 | 64 (10.3%) | 69 (12.3%) | 100 (15.5%) | 93 (15.8%) | 26 (11.2%) | - | |

| CMS4 | 116 (18.7%) | 126 (22.4%) | 134 (20.8%) | 180 (30.7%) | 69 (29.6%) | - | |

| Tumor Location | |||||||

| Right | 270 (43.6%) | 220 (39.1%) | 160 (24.8%) | 134 (22.8%) | - | - | <0.001 |

| Left | 349 (56.4%) | 342 (60.9%) | 195 (30.2%) | 410 (69.8%) | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gai, B.; Duan, X.; Li, C.; Hu, C.; Lv, M.; Lei, J.; Wang, R.; Gao, F.; Cai, D. Translating Molecular Subtypes into Cost-Effective Radiogenomic Biomarkers for Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020273

Gai B, Duan X, Li C, Hu C, Lv M, Lei J, Wang R, Gao F, Cai D. Translating Molecular Subtypes into Cost-Effective Radiogenomic Biomarkers for Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020273

Chicago/Turabian StyleGai, Baowen, Xin Duan, Chenghang Li, Chuling Hu, Minyi Lv, Jiaxin Lei, Runxian Wang, Feng Gao, and Du Cai. 2026. "Translating Molecular Subtypes into Cost-Effective Radiogenomic Biomarkers for Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020273

APA StyleGai, B., Duan, X., Li, C., Hu, C., Lv, M., Lei, J., Wang, R., Gao, F., & Cai, D. (2026). Translating Molecular Subtypes into Cost-Effective Radiogenomic Biomarkers for Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Diagnostics, 16(2), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020273