Candida albicans Meningoencephalitis After Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery: An Autopsy-Confirmed Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

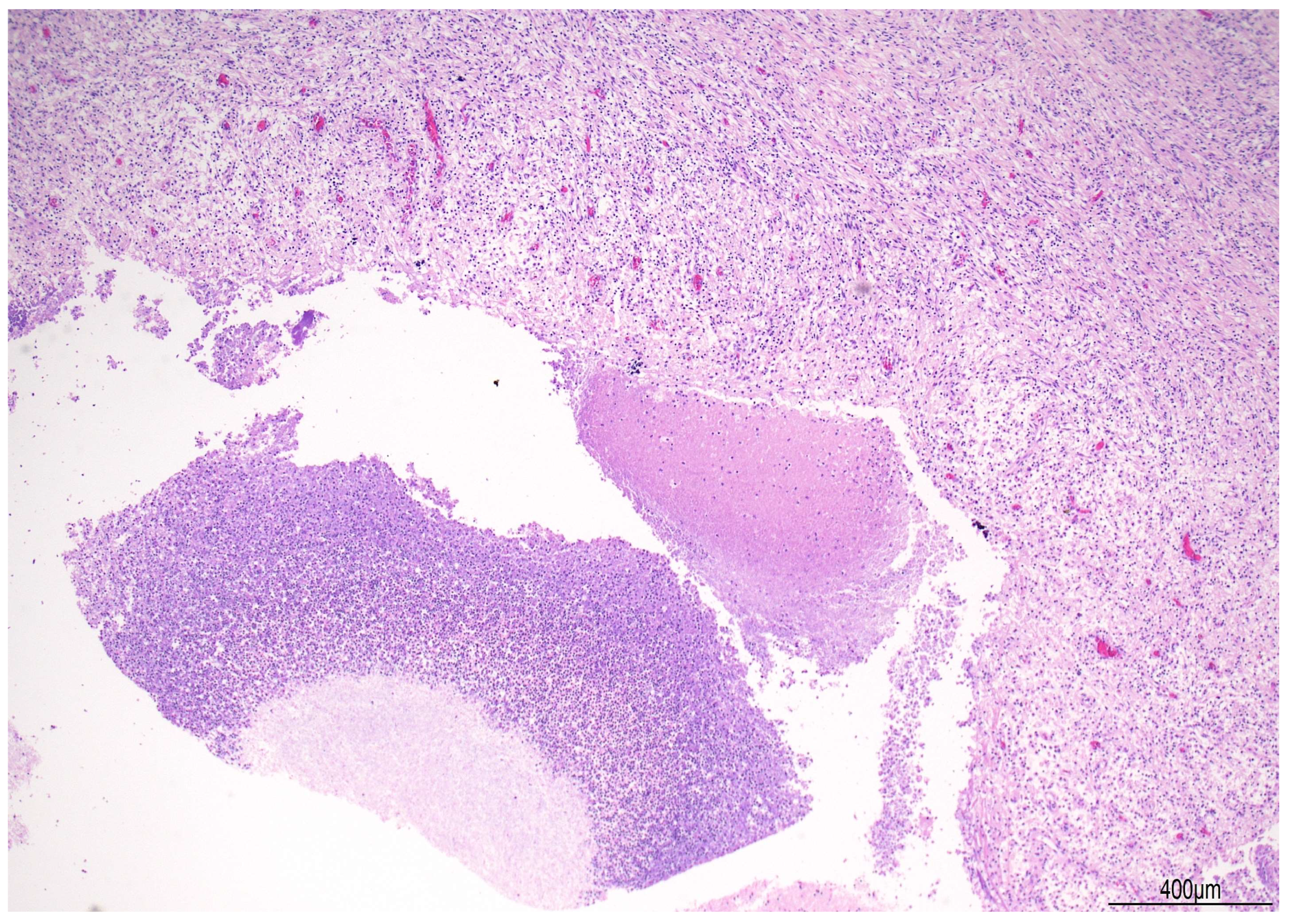

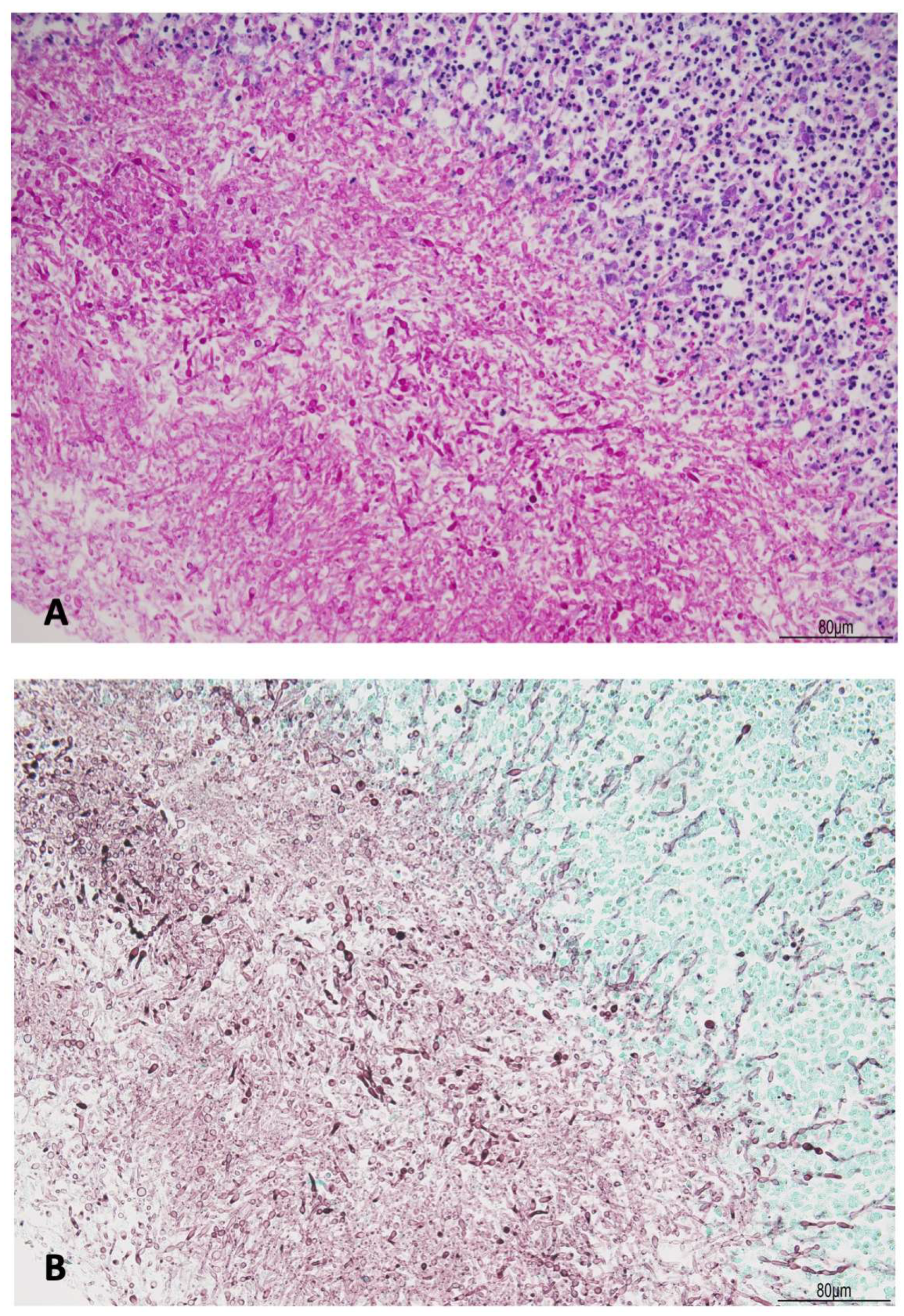

2.1. Autopsy Findings

2.2. Summary of Clinical Course

3. Discussion

3.1. Overview of the Case

3.2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

3.3. Diagnostic Challenges

3.4. Therapeutic Considerations

3.5. Role of Autopsy

3.6. Mini-Review of Published Cases

3.7. Forensic Perspective and Ancillary Methods

3.8. Medico-Legal Implications

3.9. Strengths and Limitations of the Case

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| EVD | External Ventricular Drain |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PAS-D | Periodic Acid–Schiff with Diastase |

| HAIs | Healthcare-Associated Infections |

References

- Góralska, K.; Blaszkowska, J.; Dzikowiec, M. Neuroinfections caused by fungi. Infection 2018, 46, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, D.; Stevens, N.T.; Lim, C.H.; O’Brien, D.F.; Smyth, E.; Fitzpatrick, F.; Humphreys, H. Candida infection of the central nervous system following neurosurgery: A 12-year review. Acta Neurochir. 2011, 153, 1347–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cong, W.; Xie, D.; Wang, S.; Niu, J.; Chen, G.; Dong, X.; Zhou, Q. Candida central nervous system infection after neurosurgery: A single-institution case series and literature review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 11362–11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhan, R. Candida meningitis in neurosurgical patients: A single-institute study of nine cases over 7 years. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Miao, Y.; Liu, L.; Feng, W.; Liu, S.; Guo, L.; Guo, X.; Chen, T.; Hu, B.; Hu, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of central nervous system candidiasis due to Candida albicans in children: A single-center experience. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzli, A.B.; Müller, M.D.; Z’Graggen, W.J.; Walti, L.N.; Martin, Y.; Lazarevic, V.; Schrenzel, J.; Oberli, A. Case report: Chronic Candida albicans meningitis: A rare entity diagnosed by metagenomic next-generation sequencing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1322847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Erkkinen, M.G.; Vodopivec, I. Cerebrospinal fluid (1,3)-β-d-glucan in isolated Candida meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, I.; Spettel, K.; Willinger, B. Molecular methods for the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, C.M.; Chen, T.K.; Toussi, S.S.; DeLaMora, P.; Petraitiene, R.; Finkelman, M.A.; Walsh, T.J. (1→3)-β-d-Glucan in cerebrospinal fluid as a biomarker for Candida and Aspergillus infections of the central nervous system in pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2016, 5, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaddar, A.; Kowald, G.R.; Mendonsa, J.M.; Nagarathna, S.; Veena Kumari, H.B. Optimization of cutoff values for (1→3)-β-d-glucan and galactomannan assays in cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of non-cryptococcal fungal infections of the central nervous system. Med. Mycol. 2025, 63, myaf037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, J.D.; White, P.L.; Kidd, S.E.; Goshia, T.; Fraley, S.I.; Hoenigl, M.; Thompson, G.R., III. An update on current and novel molecular diagnostics for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 23, 1135–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, A.; Honore, P.M.; Puerta-Alcalde, P.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Pagotto, A.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Verweij, P.E. Invasive candidiasis: Current clinical challenges and unmet needs in adult populations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, P.; Pollanen, M.; Daneman, N. A retrospective forensic review of unexpected infectious deaths. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Lionakis, M.S.; Arendrup, M.C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Kullberg, B.J. Invasive candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Portocarrero, J.; Pérez-Cecilia, E.; Corral, O.; Romero-Vivas, J.; Picazo, J.J. The central nervous system and infection by Candida species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2000, 37, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.E.; Andes, D.R. Contributions of the biofilm matrix to Candida pathogenesis. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, N.; Baldari, B.; Del Fante, Z.; De Simone, S.; Aromatario, M.; Cipolloni, L. Gas gangrene, not a common infection: Case report of post-traumatic fulminant death. Clin. Ter. 2022, 173, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Yu, V.L. Meningitis caused by Candida species: An emerging problem in neurosurgical patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 21, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Roos, K.L.; Marr, K.A.; Neumann, H.; Trivedi, J.B.; Kimbrough, D.J.; Steiner, L.; Thakur, K.T.; Harrison, D.M.; Zhang, S.X. Cerebrospinal fluid (1,3)-β-d-glucan detection as an aid for diagnosis of iatrogenic fungal meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1285–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigot, J.; Leroy, J.; Chouaki, T.; Cholley, L.; Bigé, N.; Tabone, M.D.; Brissot, E.; Thorez, S.; Maizel, J.; Dupont, H.; et al. β-d-Glucan assay in the cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of non-cryptococcal fungal infection of the central nervous system: A retrospective multicentric analysis and a comprehensive review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancia, M.; Bacci, M. Is it time for a guideline on the use of immunohistochemistry in forensic pathology? Egypt J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, R.; Camatti, J.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Clemente, G.M.; Nicolì, S.; Campanini, N.; Mozzoni, P. HIF-1α expression by immunohistochemistry and mRNA-210 levels by real time polymerase chain reaction in post-mortem cardiac tissues: A pilot study. Leg. Med. 2024, 71, 102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchi, R.; Ikeda, T.; Camatti, J.; Nosaka, M.; Ishida, Y.; Kondo, T. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in human skin within 1 hour after injury through immunohistochemical staining: A pilot study. Int. J. Legal Med. 2024, 138, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedouit, F.; Ducloyer, M.; Elifritz, J.; Adolphi, N.L.; Yi-Li, G.W.; Decker, S.; Ford, J.; Kolev, Y.; Thali, M. The current state of forensic imaging—Post mortem imaging. Int. J. Legal Med. 2025, 139, 1141–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessika, C.; Anna, L.S.; Stefano, D.; Bruno Giuliano, G.; Marco, B.; Riccardo, B.; Riccardo, R.; Enrico, S. Diagnosing coronary thrombosis using multiphase post-mortem CT angiography (MPMCTA): A case study. Med. Sci. Law 2021, 61 (Suppl. 1), 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camatti, J.; Santunione, A.L.; Draisci, S.; Drago, A.; Amorico, M.G.; Ligabue, G.; Silingardi, E.; Torricelli, P.; Cecchi, R. Correlation between epicardial fat volume and postmortem radiological and autopsy findings in cases of sudden death: A pilot study. Forensic Imaging 2025, 40, 200620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camatti, J.; Santunione, A.L.; Draisci, S.; Drago, A.; Amorico, M.G.; Ligabue, G.; Silingardi, E.; Torricelli, P.; Cecchi, R. Predictive value of coronary artery calcium score on radiological and autoptic findings in cases of sudden death. Forensic Imaging 2024, 39, 200610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Postoperative Time | Clinical Course | CSF/Microbiology | Imaging | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early postoperative days | Fever, neurological deterioration, hydrocephalus requiring external ventricular drain | CSF: pleocytosis, high protein; cultures negative | Ventricular enlargement (hydrocephalus) | Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics |

| ~1 month after surgery | Fluctuating consciousness, persistent fever | Intraoperative mastoid graft cultures: Candida albicans | Basal meningeal enhancement on MRI | Liposomal amphotericin B + flucytosine, later switched to fluconazole |

| Weeks 5–10 | Recurrent hydrocephalus, need for repeated drainage procedures; partial, transient improvement | CSF: inflammatory profile; intermittent Candida albicans isolation | Persistent ventricular dilation, basal meningeal enhancement | Continued antifungal therapy |

| ~3 months after surgery | Progressive neurological decline, coma, death | Autopsy: PAS-D and GMS stains positive for fungal elements (Candida albicans) | – | Supportive intensive care until death |

| Study (Year) | Design/Cohort | Setting & Risk Factors | Diagnostic Confirmation | Ancillary Tests | Treatment Notes | Outcome/Key Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nguyen & Yu (1995) [19] | Case series (n = 3) | Neurosurgical patients | CSF/tissue culture | – | Amphotericin B ± flucytosine | Highlighted CNS candidiasis as an emerging complication in neurosurgery; poor prognosis. |

| Sánchez-Portocarrero et al. (2000) [16] | Review | Mixed: meningitis & abscesses; device-related | Literature-based | – | Amphotericin B + flucytosine | Classic overview stressing device role and high mortality. |

| O’Brien et al. (2011) [2] | 12-year institutional review | Post-neurosurgical; foreign body implants | Culture/histology | – | Device removal + antifungals | Confirmed strong link with foreign material; guarded prognosis. |

| Chen et al. (2020) [4] | Series (n = 9) | 8/9 device-associated (VPS, LPS, EVD) | Serial CSF cultures | – | Fluconazole/voriconazole; hardware removal | Mortality 11.1%; survivors with severe sequelae. |

| Chen et al. (2021) [3] | Series + review | Post-neurosurgical; prior bacterial CNS infection common | CSF culture (delayed positivity) | – | Amphotericin B + azoles; device strategy | Emphasized diagnostic delays. |

| Lyons et al. (2013, 2015) [7,20] | Case reports | Meningitis, some iatrogenic | Culture/clinical | CSF β-d-glucan | Antifungals per case | β-d-glucan useful when cultures negative. |

| Bigot et al. (2023) [21] | Multicenter retrospective | Non-cryptococcal fungal CNS infections | Composite reference | CSF β-d-glucan | – | BDG promising but not standardized. |

| Kuenzli et al. (2024) [6] | Case report | Shunt-associated chronic meningitis | mNGS on CSF | mNGS | Targeted azoles | Showed diagnostic delay, value of molecular methods. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Camatti, J.; Tudini, M.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Santunione, A.L.; Cecchi, R.; Radheshi, E.; Carretto, E. Candida albicans Meningoencephalitis After Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery: An Autopsy-Confirmed Case Report. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020228

Camatti J, Tudini M, Bonasoni MP, Santunione AL, Cecchi R, Radheshi E, Carretto E. Candida albicans Meningoencephalitis After Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery: An Autopsy-Confirmed Case Report. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020228

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamatti, Jessika, Matteo Tudini, Maria Paola Bonasoni, Anna Laura Santunione, Rossana Cecchi, Erjon Radheshi, and Edoardo Carretto. 2026. "Candida albicans Meningoencephalitis After Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery: An Autopsy-Confirmed Case Report" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020228

APA StyleCamatti, J., Tudini, M., Bonasoni, M. P., Santunione, A. L., Cecchi, R., Radheshi, E., & Carretto, E. (2026). Candida albicans Meningoencephalitis After Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery: An Autopsy-Confirmed Case Report. Diagnostics, 16(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020228