First Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica with Critical Vocal Cord Involvement: Proposing a Novel Pathophysiological Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

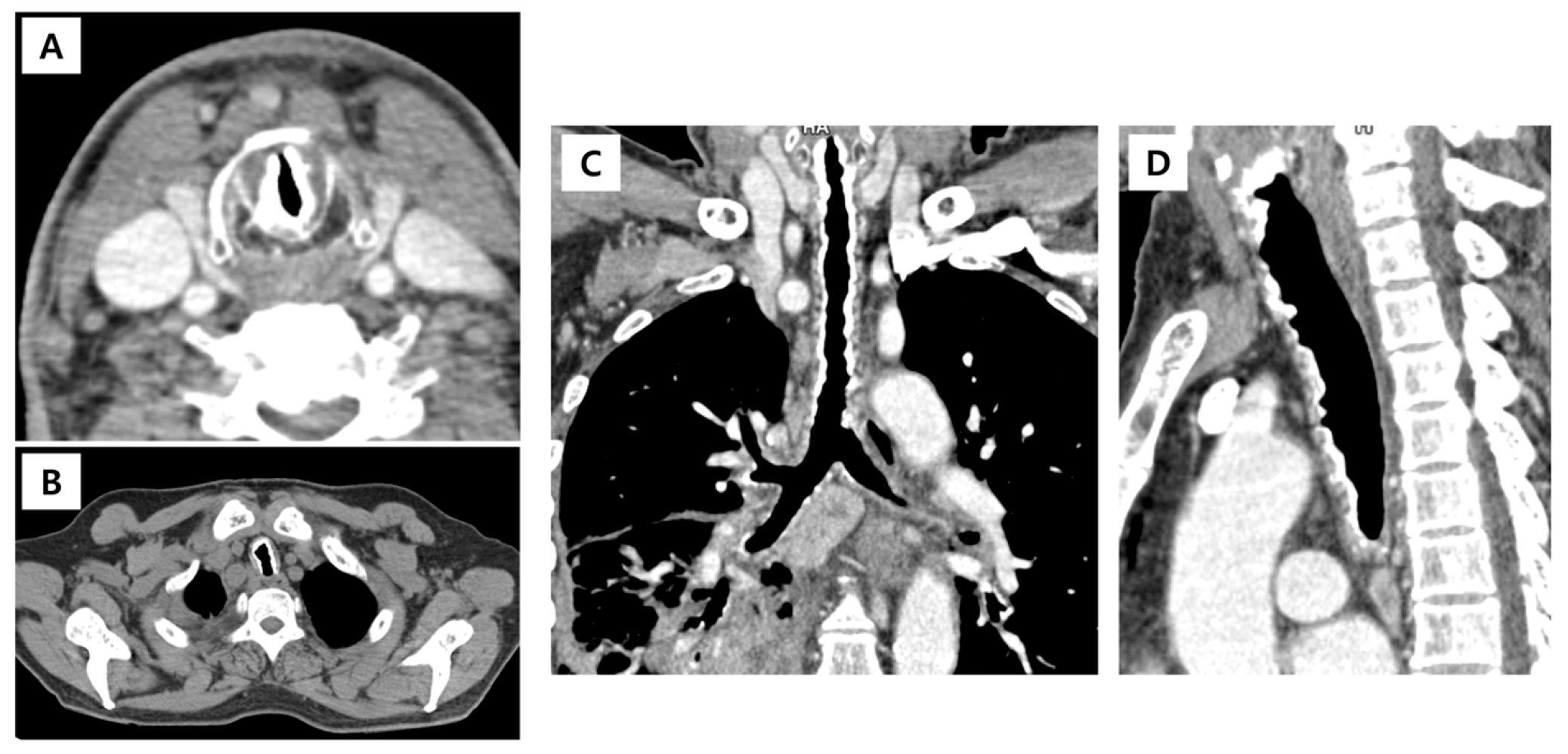

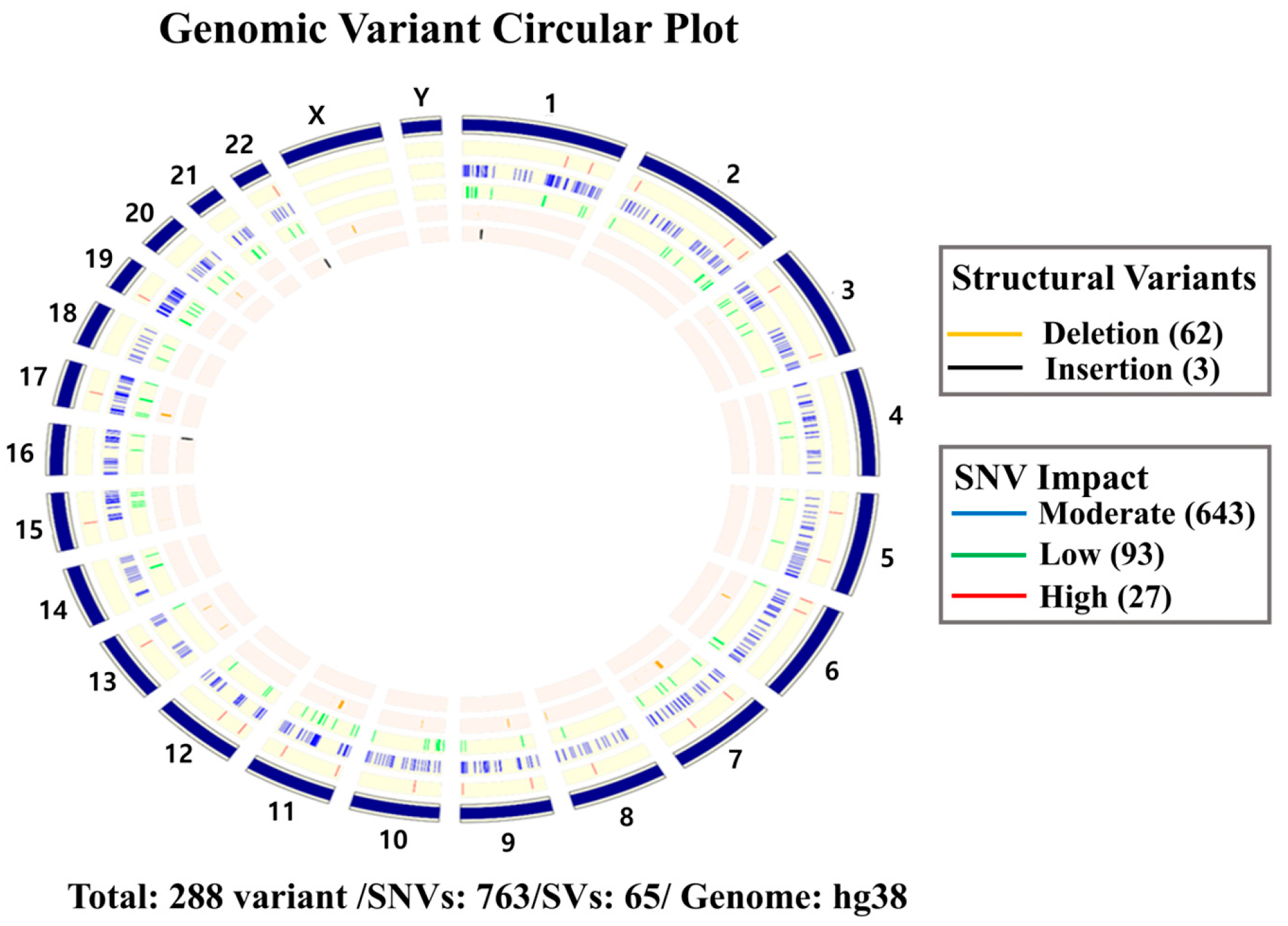

2. Case Presentation

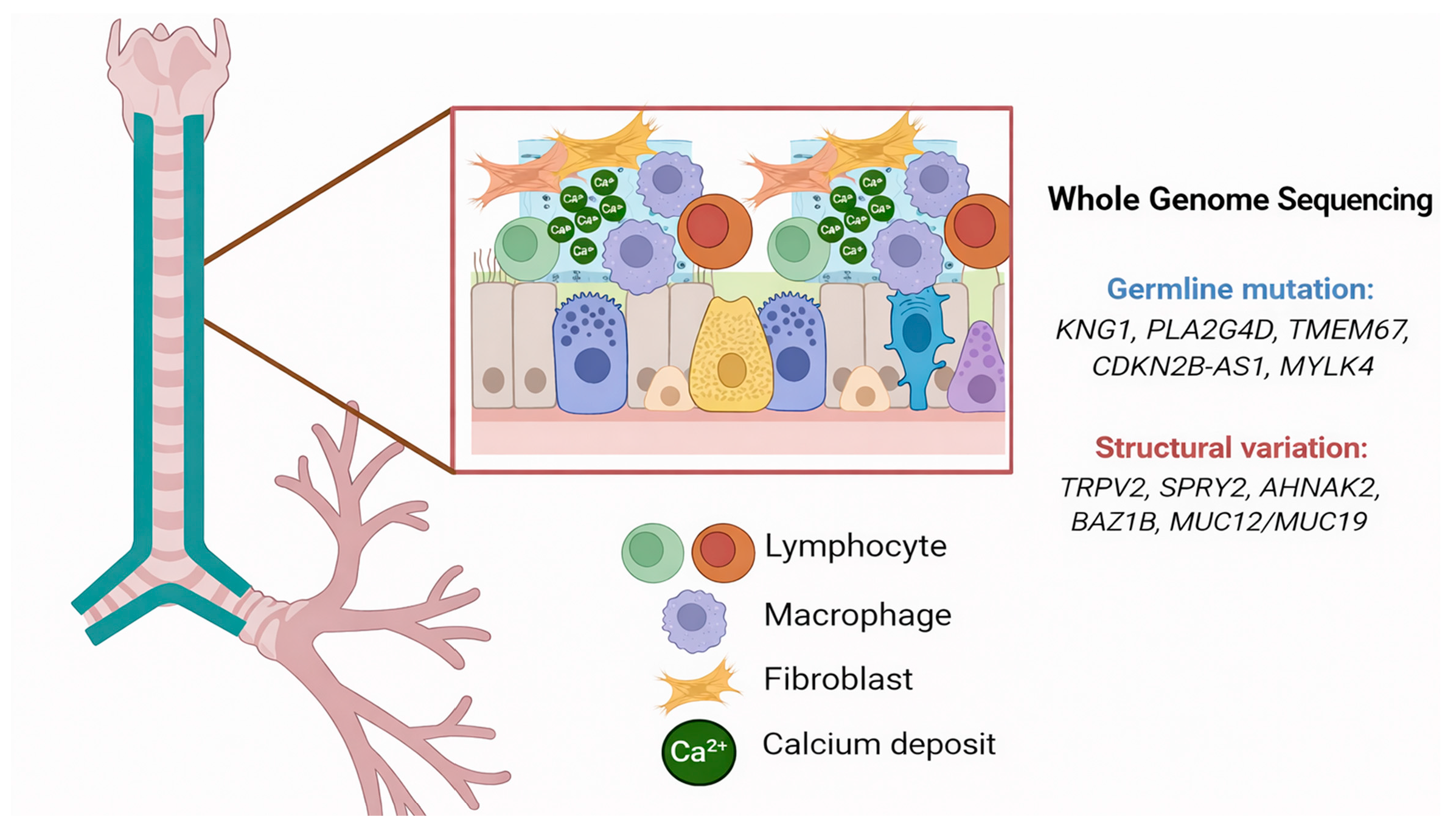

3. Discussion

Literature Review

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TO | Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale |

| GOLD | The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| SNVs | Single-nucleotide variants |

| Indesls | Insertions/deletions |

| VEP | Variant Effect Predictor |

| SVs | Structural variants |

References

- Sun, J.; Xie, L.; Su, X.; Zhang, X. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: Case report and literature review. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2015, 15, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, G.; Girolami, I.; Luchini, C.; Villanova, M.; Valotto, G.; Cima, L.; Carella, R.; Riva, M.; Fraggetta, F.; Novelli, L.; et al. Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica: A Case Report Illustrating the Importance of Multilevel Workup Clinical, Endoscopic and Histological Assessment in Diagnosis of an Uncommon Disease. Am. J. Case Rep. 2019, 20, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Wu, L.; Zhou, J.; Xu, S.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhang, S. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: Two cases and a review of the literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 9681–9686. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, U.B. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 23, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, M.; Gomes, R.; Moreira, C.; Soares, J. Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica: Two Different Facets of a Rare Entity. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2020, 7, 001925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danckers, M.; Raad, R.A.; Zamuco, R.; Pollack, A.; Rickert, S.; Caplan-Shaw, C. A complication of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica presenting as acute hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am. J. Case Rep. 2015, 16, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, H.; Thankachen, R.; Philip, M.A.; Kurien, S.; Shukla, V.; Korula, R.J. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica presenting as an isolated nodule in the right upper lobe bronchus with upper lobe collapse. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 130, 901–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, P.; Gui, Y.; Qin, C.; Huang, S.; Qi, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, F. KNG1 mutations (c.618 T > G and c.1165C > T) cause disruption of the Cys206-Cys218 disulfide bond and truncation of the D5 domain leading to hereditary high molecular weight kininogen deficiency. Clin. Biochem. 2025, 136, 110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Chen, J.; Swindell, W.R.; Tsoi, L.C.; Xing, X.; Ma, F.; Uppala, R.; Sarkar, M.K.; Plazyo, O.; Billi, A.C.; et al. Phospholipase A2 enzymes represent a shared pathogenic pathway in psoriasis and pityriasis rubra pilaris. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e151911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Nam, T.S.; Li, W.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, W.; Choi, Y.D.; Kim, K.H.; Cai, H.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, C.; et al. Functional validation of novel MKS3/TMEM67 mutations in COACH syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leightner, A.C.; Hommerding, C.J.; Peng, Y.; Salisbury, J.L.; Gainullin, V.G.; Czarnecki, P.G.; Sussman, C.R.; Harris, P.C. The Meckel syndrome protein meckelin (TMEM67) is a key regulator of cilia function but is not required for tissue planar polarity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 2024–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Esparragon, F.; Torres-Mata, L.B.; Cazorla-Rivero, S.E.; Serna Gomez, J.A.; Gonzalez Martin, J.M.; Canovas-Molina, A.; Medina-Suarez, J.A.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, A.N.; Estupinan-Quintana, L.; Bartolome-Duran, M.C.; et al. Analysis of ANRIL Isoforms and Key Genes in Patients with Severe Coronary Artery Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Lin, W.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Ho, W.Y.; Fu, C.W.; Tu, C.M.; Hwang, C.S.; Hung, C.L.; Lin, M.C.; Cheng, F.; et al. The Intraocular Pressure Lowering Effect of a Dual Kinase Inhibitor (ITRI-E-(S)4046) in Ocular Hypertensive Animal Models. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdsson, M.I.; Waldron, N.H.; Bortsov, A.V.; Smith, S.B.; Maixner, W. Genomics of Cardiovascular Measures of Autonomic Tone. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 71, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, H.; Katanosaka, Y.; Chijimatsu, R.; Mori, D.; Xuan, F.; Yano, F.; Omata, Y.; Maenohara, Y.; Murahashi, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.; et al. Involvement of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Channel 2 in the Induction of Lubricin and Suppression of Ectopic Endochondral Ossification in Mouse Articular Cartilage. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesela, B.; Svandova, E.; Hovorakova, M.; Peterkova, R.; Kratochvilova, A.; Pasovska, M.; Ramesova, A.; Lesot, H.; Matalova, E. Specification of Sprouty2 functions in osteogenesis in in vivo context. Organogenesis 2019, 15, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, G.; Guo, Z. Inhibition of AHNAK nucleoprotein 2 alleviates pulmonary fibrosis by downregulating the TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling pathway. J. Gene Med. 2022, 24, e3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, M.; Schlingmann, K.P.; Berezin, L.; Molin, A.; Sheftel, J.; Vig, M.; Gallagher, J.C.; Nagata, A.; Masoud, S.S.; Sakamoto, R.; et al. Differential diagnosis of vitamin D-related hypercalcemia using serum vitamin D metabolite profiling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lee, P.; Yu, D.; Tao, S.; Chen, Y. Cloning and characterization of human MUC19 gene. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 45, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leske, V.; Lazor, R.; Coetmeur, D.; Crestani, B.; Chatte, G.; Cordier, J.F. Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines, P. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: A study of 41 patients. Medicine 2001, 80, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantous-Zannad, S.; Sebai, L.; Zidi, A.; Ben Khelil, J.; Mestiri, I.; Besbes, M.; Hamzaoui, A.; Ben Miled-M’rad, K. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica presenting as a respiratory insufficiency: Diagnosis by bronchoscopy and MRI. Eur. J. Radiol. 2003, 45, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, N.; Huang, H.D.; Dong, Y.C.; Sun, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q. A clinical study of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: Findings from a large Chinese cohort. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulasli, S.S.; Kupeli, E. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: A review of the literature. Clin. Respir. J. 2015, 9, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.A.; Sangiovanni, S.; Zuniga-Restrepo, V.; Morales, E.I.; Sua, L.F.; Fernandez-Trujillo, L. Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica-Clinical, Radiological, and Endoscopic Correlation: Case Series and Literature Review. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2020, 8, 2324709620921609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Lei, M.; Mei, C.; Yang, C. Clinical Characteristics of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica: A Retrospective Study of 33 Patients. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 3447–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S.; Ray, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Balaji, B. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: A rare case of misdiagnosis and difficult intubation. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2022, 52, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lim, Y. Difficult endotracheal intubation in a patient with progressed tracheobronchopathia osteoplastica: A case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2024, 19, 2954–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, G.M.; Natal, M.R.; Silva, E.F.; Freitas, S.C.; Moraes, W.C.; Maciel, F.C. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: Computed tomography, bronchoscopy and histopathological findings. Radiol. Bras. 2016, 49, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Busaidi, N.; Dhuliya, D.; Habibullah, Z. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: Case report and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2012, 12, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumazet, A.; Launois, C.; Lebargy, F.; Kessler, R.; Vallerand, H.; Schmitt, P.; Hermant, C.; Dury, S.; Dewolf, M.; Dutilh, J.; et al. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: Clinical, bronchoscopic, and comorbid features in a case series. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhou, M.; Wei, X.; Niu, L. Clinical Characteristics of Six Cases of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica. Can. Respir. J. 2020, 2020, 8685126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.K.; Jeong, B.H.; Kim, H. Clinical course of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 5571–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Arul, L.; Sreekumar, G.; Mathew, J. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: An unanticipated difficult airway. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 41, 751–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraja, K.; Surendra, V.U. Clinicopathological Features and Management Principles of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica—A Scoping Review. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 3798–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, M.G.M.; Castellano, M.; Fuzi, C.E.; Coletta, E.; Spinosa, G.N. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2017, 43, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Zhou, H.; Meng, J. Clinical Characteristics of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica. Respir. Care 2019, 64, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, K.; Yamakawa, M.; Katagiri, T.; Sasaki, H. Immunohistochemical detection of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and transforming growth factor beta-1 in tracheopathia osteochondroplastica. Virchows Arch. 1997, 431, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Shan, S.; Gu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Y.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, M.; Ren, T. Malfunction of airway basal stem cells plays a crucial role in pathophysiology of tracheobronchopathia osteoplastica. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, P.O.; Ozcelik, U.; Demirkazik, F.; Unal, O.F.; Orhan, D.; Aslan, A.T.; Dogru, D. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica in a 9-year-old girl. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2006, 41, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, C.C.; Pires-de-Mello, P.; Morgado Mde, F.; March Mde, F. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica in a 5 year-old girl. Indian Pediatr. 2012, 49, 985–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, H.; Tang, W.; Li, L. Tracheobronchial ossification in children: A case report and review of the literature. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1552947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafili, D.; Sampson, T.; Tolhurst, S. Difficult intubation in an asymptomatic patient with tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Respirol. Case Rep. 2020, 8, e00526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Variant Type | Functional Effect | Pathway Involved | Clinical Implication | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNG1 | Nonsense | Coagulation/inflammation dysregulation | Tissue damage, vascular permeability | Dystrophic calcification | [8] |

| PLA2G4D | Missense | Altered arachidonic acid metabolism | Chronic inflammation, ECM remodeling | Tissue calcification | [9] |

| TMEM67 | Splice site | Ciliary dysfunction | Wnt/Hedgehog signaling | Abnormal mineralization | [10,11] |

| CDKN2B-AS1 | Frameshift | Dysregulated lncRNA function | Cell proliferation, atherosclerosis | Vascular calcification | [12] |

| MYLK4 | Missense | Smooth muscle dysfunction | Vascular tone regulation | Coronary artery calcification | [13,14] |

| Gene | SV Type | Functional Effect | Pathway Involved | Clinical Implication | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV2 | Gene fusion | Calcium channel dysfunction | Osteogenic differentiation | Ectopic calcification | [15] |

| SPRY2 | Deletion | ERK/Wnt signaling alteration | Osteogenesis modulation | Promotion of abnormal calcification | [16] |

| AHNAK2 | Insertion | Dysregulated TGF-β/SMAD signaling | Fibrosis, inflammation | Calcification-prone microenvironment | [17] |

| BAZ1B | Deletion | Calcium homeostasis defect | Hypercalcemia | Soft tissue calcification | [18] |

| MUC12/MUC19 | Gene fusion | Impaired mucosal barrier | Chronic epithelial injury | Tracheobronchial calcification | [19] |

| First Author (Year) | Patient Characteristics | Finding | Management | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leske (2001) | 41-patient cohort; one highlighted case | One patient presented with acute respiratory failure; intubation attempts failed due to severe tracheal stenosis | Emergency tracheostomy | Maintained on long-term home mechanical ventilation because of severe tracheal stenosis | [20] |

| Hantous-Zannad (2003) | 42-year-old male, non-smoker | Tracheal narrowing with consolidation of LLL; extensive and multiple grey/white nodules with scattered calcifications in the main and lobar bronchi | Oxygen therapy; antibiotics | Improved; resolution of consolidation | [21] |

| Danckers (2015) | 27-year-old male | Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure; subglottic mass with cystic and solid component obstructing 75% of the airway | Intubation, mechanical ventilation; surgical drainage; prophylactic tracheostomy; antibiotics | Asymptomatic after tracheostomy removal; persistent vocal cord fixation | [6] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, Y.; Lee, J.-E.; Lim, M.J.; Kang, H.S.; Chung, C. First Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica with Critical Vocal Cord Involvement: Proposing a Novel Pathophysiological Model. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020210

Park Y, Lee J-E, Lim MJ, Kang HS, Chung C. First Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica with Critical Vocal Cord Involvement: Proposing a Novel Pathophysiological Model. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020210

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Yeonhee, Joo-Eun Lee, Mi Jung Lim, Hyeong Seok Kang, and Chaeuk Chung. 2026. "First Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica with Critical Vocal Cord Involvement: Proposing a Novel Pathophysiological Model" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020210

APA StylePark, Y., Lee, J.-E., Lim, M. J., Kang, H. S., & Chung, C. (2026). First Whole-Genome Sequencing Analysis of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica with Critical Vocal Cord Involvement: Proposing a Novel Pathophysiological Model. Diagnostics, 16(2), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020210