A Ruptured Tri-Lobulated ICA–PCom Aneurysm Presenting with Preserved Neurological Function: Case Report and Clinical–Anatomical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

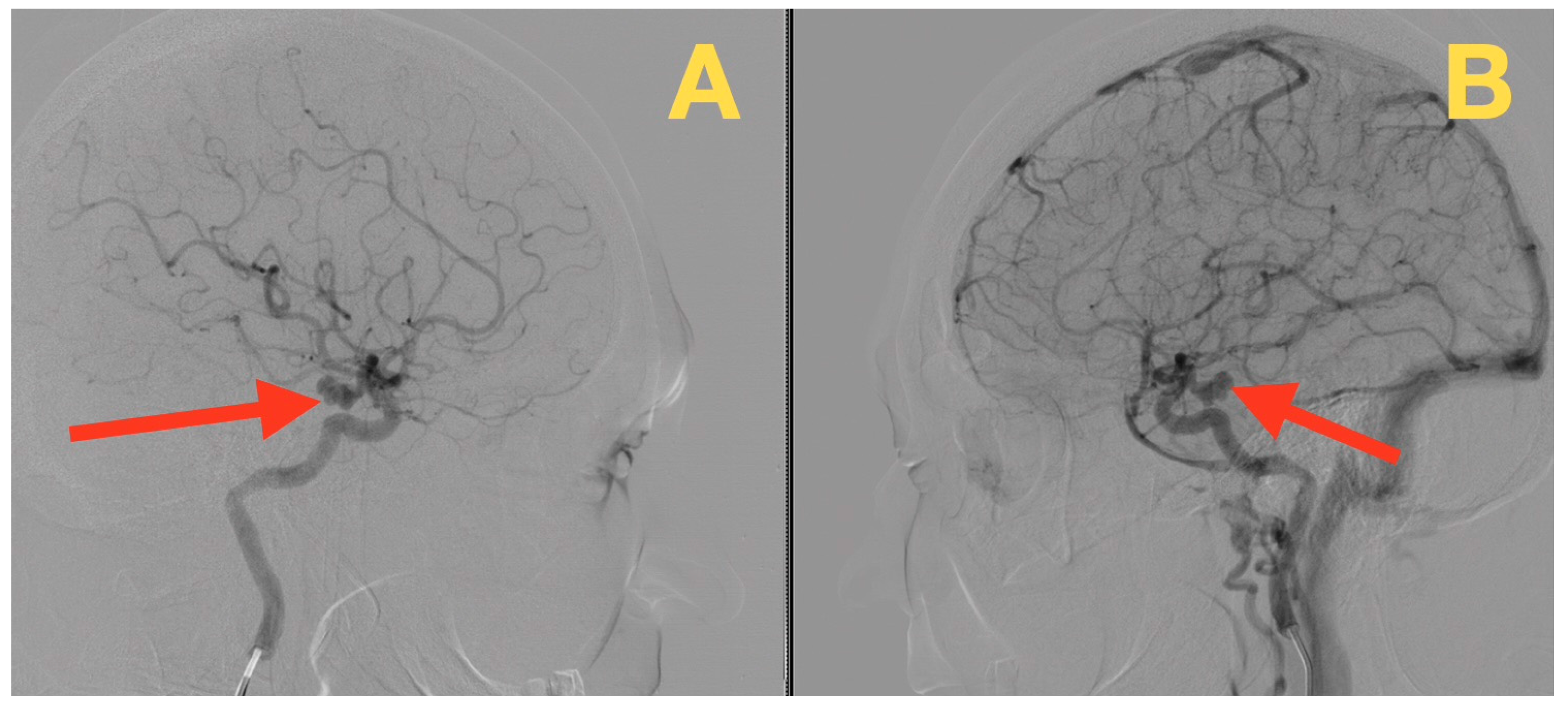

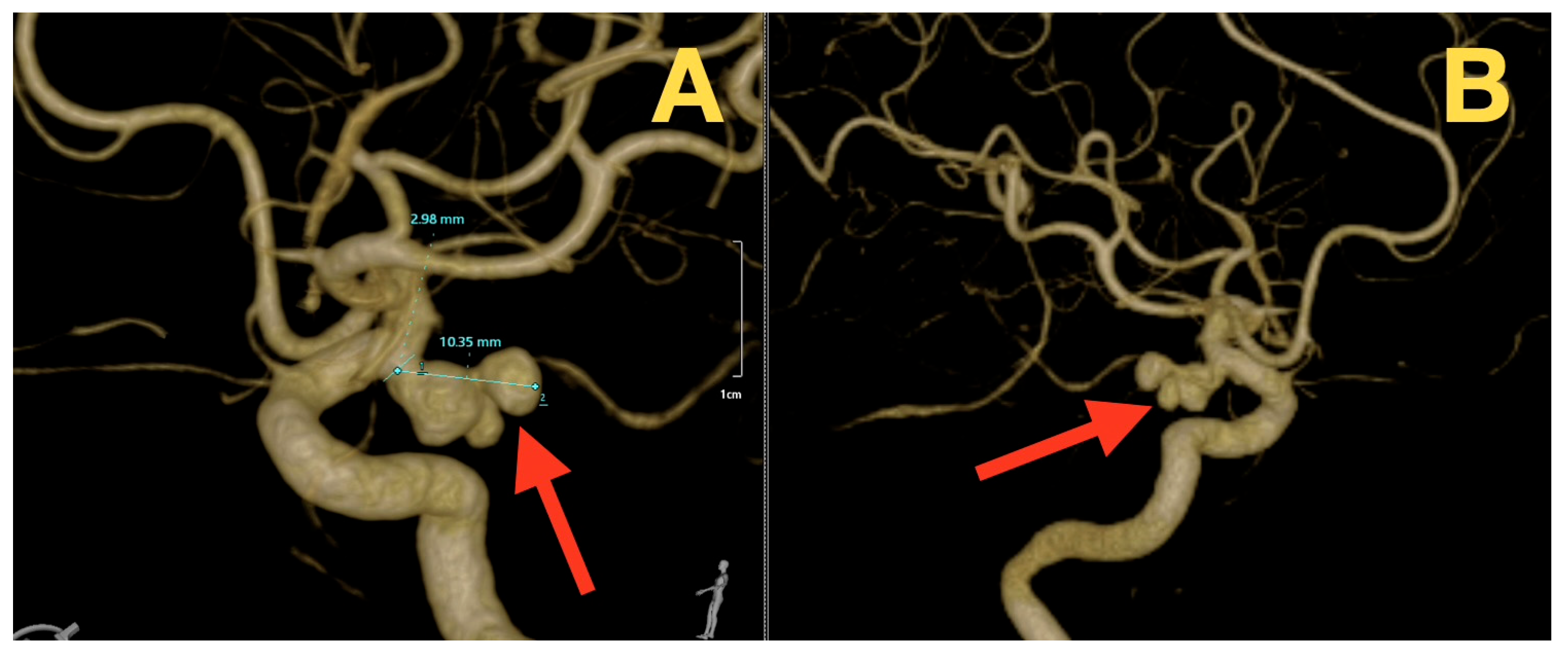

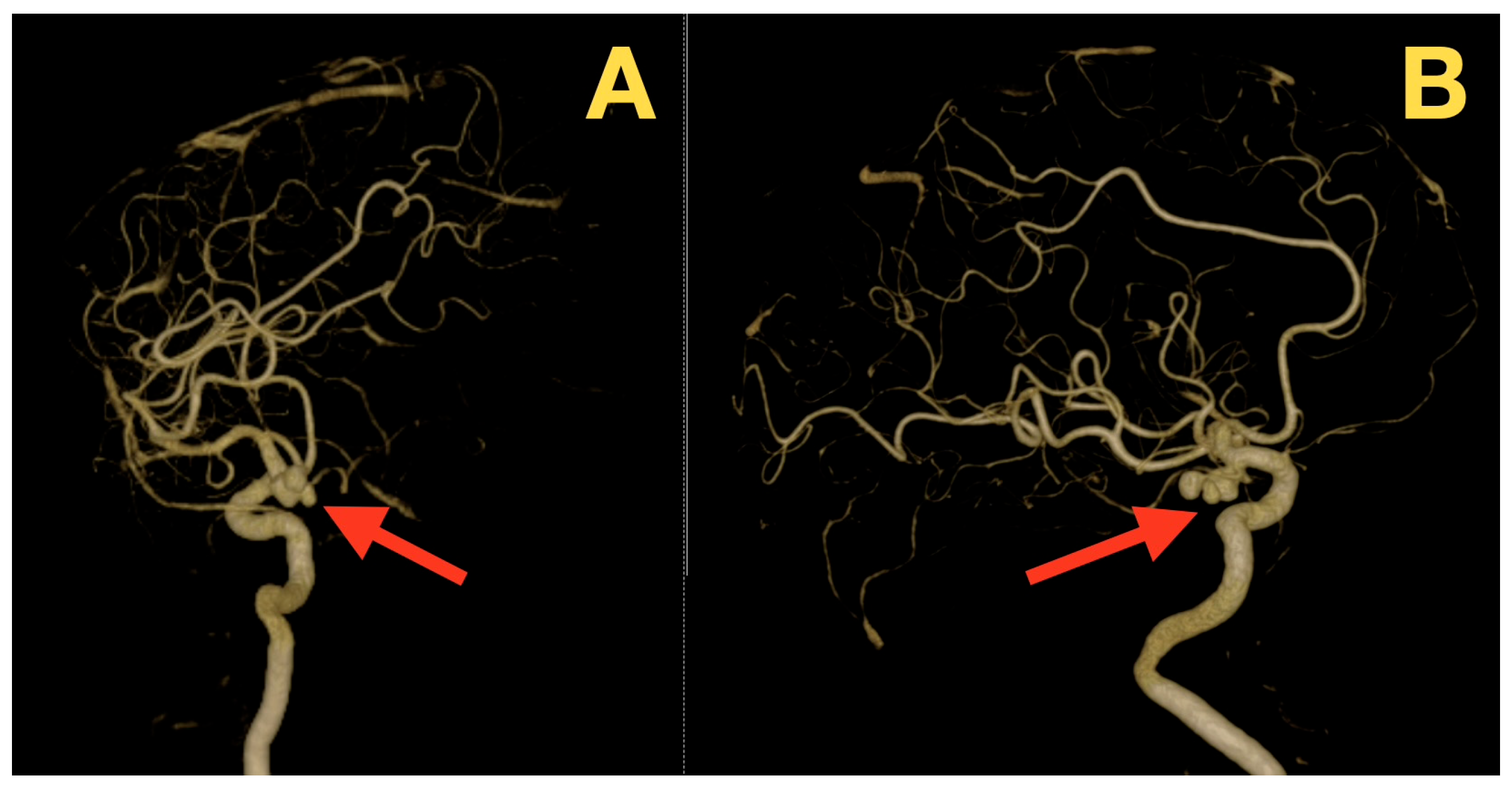

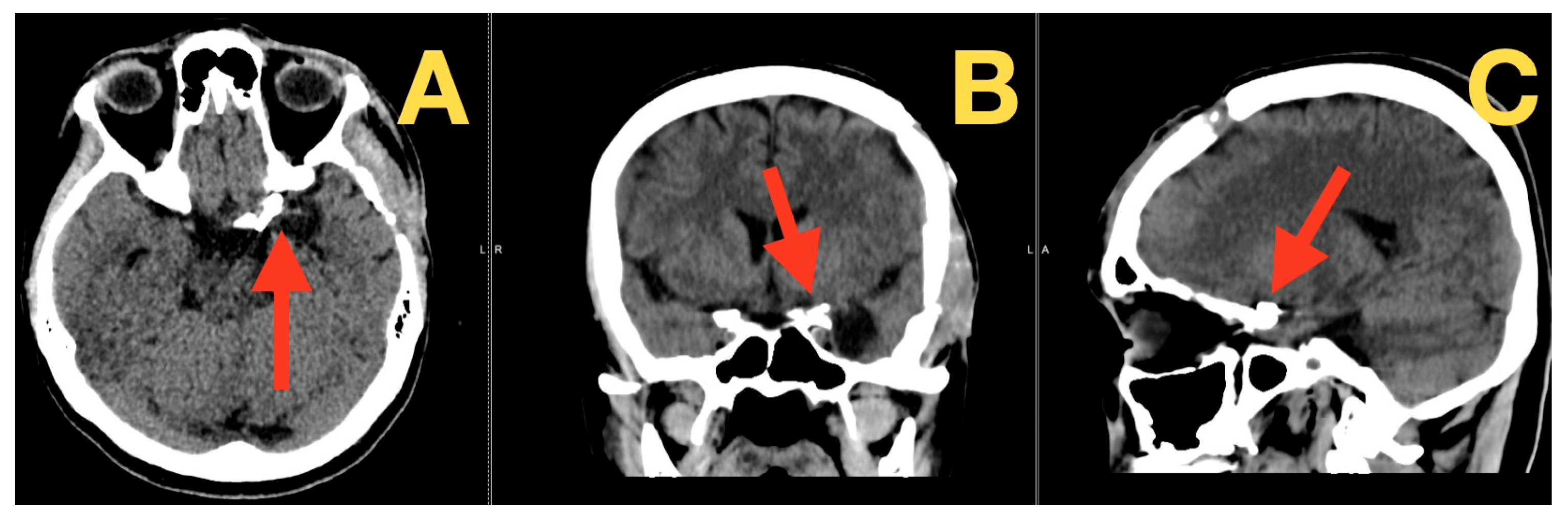

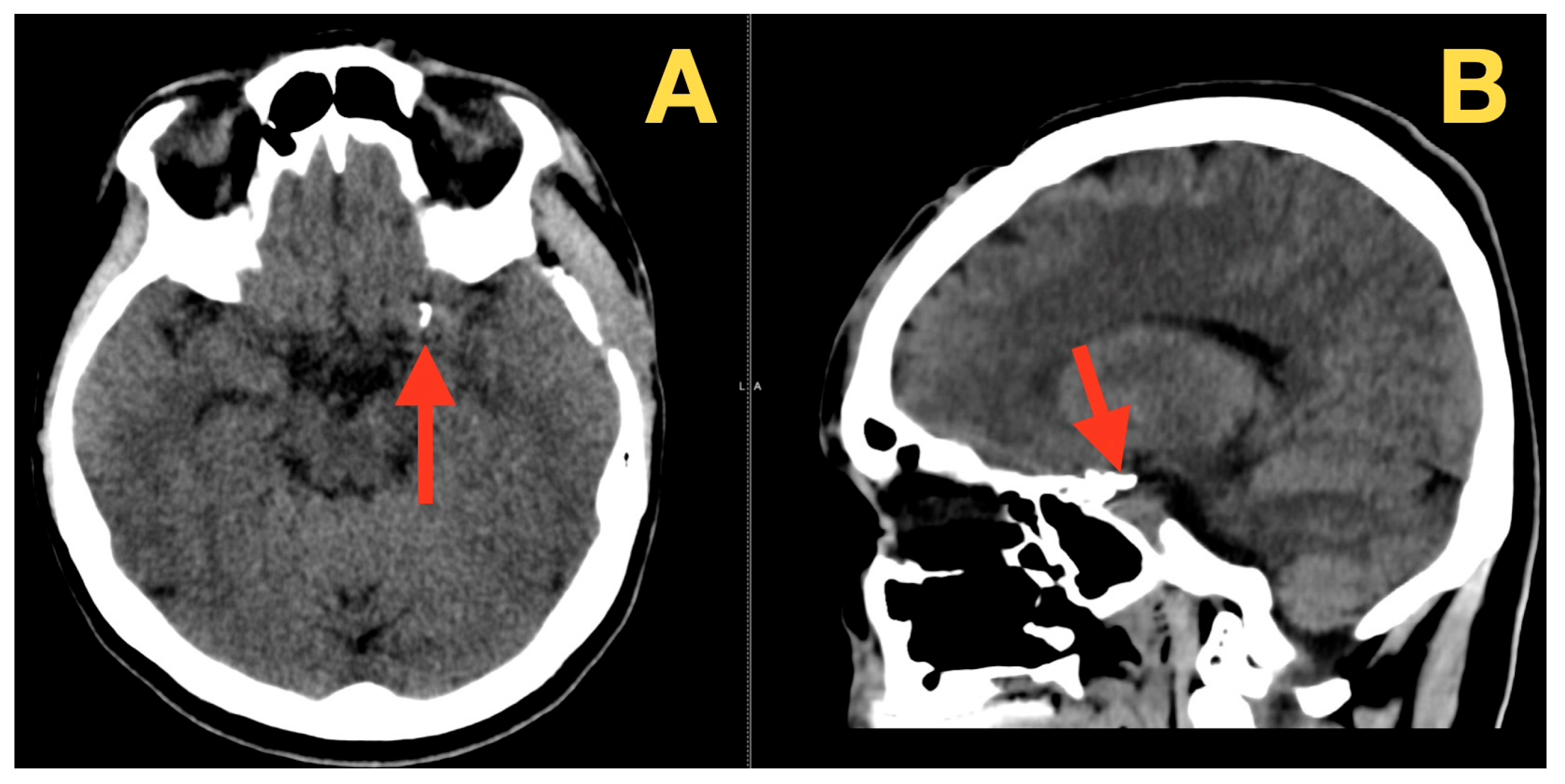

2. Case Presentation

- •

- Most likely diagnosis: Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); based on the characteristics of the headache, the intensity of pain at onset, the pronounced meningeal signs and photophobia, and the lack of focal neurological deficits (Hunt–Hess 1; WFNS 1; NIHSS 0).

- •

- Second most likely diagnosis: Non-aneurysmal perimesencephalic SAH; this is less likely given the total clinical intensity of the presentation and the nature of the pain-provoking mechanisms.

- •

- Third most unlikely diagnosis: Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS); unlikely based on the absence of multiple episodes of thunderclap headaches and typical precipitating events;

- •

- Fourth least likely diagnosis: Thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinuses; unlikely given the absence of papilledema, seizures, and progressive clinical deterioration;

- •

- Fifth least likely diagnosis: Dissection of a cervical artery; unlikely given the absence of focal pain syndrome or cranial nerve deficits;

- •

- Sixth least likely diagnosis: Infectious meningitis; unlikely given the instantaneous onset of symptoms, afebrile state, and the absence of preceding symptoms.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robba, C.; Busl, K.M.; Claassen, J.; Diringer, M.N.; Helbok, R.; Park, S.; Rabinstein, A.; Treggiari, M.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; Citerio, G. Contemporary Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. An Update for the Intensivist. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. Subtemporal Approach for Posterior Communicating Artery Aneurysms. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1518117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, H.; Tsutsumi, S.; Ishii, H. Oculomotor Nerve Palsy Presumably Caused by Cisternal Drain during Microsurgical Clipping. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2022, 13, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, P.; AlMatter, M.; Hellstern, V.; Ganslandt, O.; Bäzner, H.; Henkes, H.; Pérez, M.A. Difference in Aneurysm Characteristics between Ruptured and Unruptured Aneurysms in Patients with Multiple Intracranial Aneurysms. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2018, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Deng, P.; Ma, M.; Tang, X.; Qian, J.; Wu, G.; Gong, Y.; Gao, L.; Zou, R.; Leng, X.; et al. How Does the Recurrence-Related Morphology Characteristics of the Pcom Aneurysms Correlated with Hemodynamics? Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1236757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoletano, G.; Di Fazio, N.; Delogu, G.; Del Duca, F.; Maiese, A. Traumatic Aneurysm Involving the Posterior Communicating Artery. Healthcare 2024, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Sebastian, L.J.D.; Gaikwad, S.; Srivastava, M.V.P.; Sharma, M.C.; Singh, M.; Bhatia, R.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, J.; Dash, D.; et al. The Role of Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging & Contrast-Enhanced MRI in the Diagnosis of Primary CNS Vasculitis: A Large Case Series. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, M.; Aoki, T. Mechanisms of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: An Integrative Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiatek, V.M.; Voss, S.; Sprenger, F.; Fischer, I.; Kader, H.; Stein, K.-P.; Schwab, R.; Saalfeld, S.; Rashidi, A.; Behme, D.; et al. Predictive Modeling and Machine Learning Show Poor Performance of Clinical, Morphological, and Hemodynamic Parameters for Small Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Mandl, D.; Föttinger, F.; Salman, S.D.; Godasi, R.; Wei, Y.; Tawk, R.G.; Freeman, W.D. The eSAH Score: A Simple Practical Predictive Model for SAH Mortality and Outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mufti, F.; Mayer, S.A.; Kaur, G.; Bassily, D.; Li, B.; Holstein, M.L.; Ani, J.; Matluck, N.E.; Kamal, H.; Nuoman, R.; et al. Neurocritical Care Management of Poor-Grade Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Unjustified Nihilism to Reasonable Optimism. Neuroradiol. J. 2021, 34, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, M.; Rajpal, G. Endovascular Treatment of Ruptured Broad-Necked Intracranial Aneurysms with Double Microcatheter Technique: Case Series with Brief Review of Literature. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2024, 19, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranawetter, B.; Chacón-Quesada, T.; Mielke, D.; Malinova, V.; Rohde, V.; Hernández-Durán, S. Microsurgical Clipping of Ruptured Wide-Neck Aneurysms: A Comparative Analysis with Woven EndoBridge Data. Brain Spine 2025, 5, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajima, D.; Kamide, T.; Nakada, M. Clinical Features and Post-Coiling Outcomes of Symptomatic Internal Carotid Artery–Posterior Communicating Artery Aneurysms: A Case Series and Literature Review. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2025, 20, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, C.R.; Lacy, A.J.; Long, B.; Koyfman, A.; Kircher, C.E. High Risk and Low Incidence Diseases: Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 92, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvea, A.; Miyake, S.; Agid, R.; Barazarte, H.A.; Farb, R.; Krings, T.; Mosimann, P.J.R.; Nicholson, P.J.; Radovanovic, I.; Terbrugge, K.; et al. Clinical and Anatomical Characteristics of Perforator Aneurysms of the Posterior Cerebral Artery: A Single-Center Experience. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernic, C.; Tamas, T.P.; Petre, I.; Ursoniu, S. Transforming Critical Care: The Digital Revolution’s Impact on Intensive Care Units. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1664382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, V.; Santos, B.; Figueiras, A.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F. The Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Innovation: From Drug Discovery to Clinical Trials. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, S.M.; Rayessa, R.; Esisi, B. Diagnostic Challenges of Focal Neurological Deficits during an Acute Take—Is This Vascular? Clin. Med. 2024, 24, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, A.; Miyake, S.; Kee, T.P.; Andrade-Barazarte, H.; Krings, T. Management of Anterior Choroidal Artery Aneurysms: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, P.; Di Fazio, B.; Dulcetta, L.; Carbone, F.S.; Muglia, R.; Bonaffini, P.A.; Valle, C.; Corvino, F.; Giurazza, F.; Muscogiuri, G.; et al. Embolization in Pediatric Patients: A Comprehensive Review of Indications, Procedures, and Clinical Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreão, F.F.; Feitosa Filho, H.N.; Barros, E.A.; Abreu Moreira, J.G.; Hemais, M.; Neto, A.R.; Almeida, L.G.S.; Pacheco-Barrios, N.; Carneiro, T.A.; Nespoli, V.S.; et al. Endovascular or Microsurgical? Defining the Best Approach for Blood Blister Aneurysms: A Comparative Meta-Analysis. Neuroradiol. J. 2025, 19714009251346467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giotta Lucifero, A.; Baldoncini, M.; Bruno, N.; Galzio, R.; Hernesniemi, J.; Luzzi, S. Shedding the Light on the Natural History of Intracranial Aneurysms: An Updated Overview. Medicina 2021, 57, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C.; Sanchin, A.; Joerger, A.-K.; Delbridge, C.; Boeckh-Behrens, T.; Wantia, N.; Wunderlich, S.; Wessels, L.; Vajkoczy, P.; Meyer, B.; et al. Mycotic Aneurysms as a Rare Cause of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaie, A. Emerging Imaging Techniques and Clinical Insights in Traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Brain Injury. Neuroimaging 2026, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogut, E. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Medicine: Challenges Across Diagnostic Imaging, Clinical Decision Support, Surgery, Pathology, and Drug Discovery. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busnatu, Ș.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Bolocan, A.; Petrescu, G.E.D.; Păduraru, D.N.; Năstasă, I.; Lupușoru, M.; Geantă, M.; Andronic, O.; Grumezescu, A.M.; et al. Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence—An Updated Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| References | Design/Cohort | Key Population | Therapy | Outcomes | Practice-Relevant Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | Rupture-mechanism synthesis | Intracranial aneurysms (incl. ICA–PCom) | — | Conceptual determinants of rupture | Use as background only; avoid patient-level mechanistic claims. |

| [9] | Imaging + modeling literature | Irregular/multilobulated aneurysms | — | Geometry ↔ heterogeneous flow descriptors | Supports statement that irregular morphology is “higher-risk/less predictable,” but do not imply patient-specific hemodynamics unless performed. |

| [10] | Clinical–anatomical framework | aSAH with basal cisternal blood | Standard SAH care | Severe symptoms can occur with limited hemorrhage in compact cisterns | Justifies “high symptom intensity despite preserved focal exam” as clinically plausible; keep language clinical, not mechanistic. |

| [11] | Course/complication context | aSAH across grades | Neurocritical monitoring | Secondary processes (hydrocephalus, sedation, vasospasm/DCI) obscure early exam | Supports value of early bedside phenotype capture in low-grade presentations. |

| [12] | Endovascular feasibility/limits | Ruptured complex aneurysms (lobulated, daughter sacs, broad neck, branch-adjacent) | Coiling ± adjuncts | Durability/packing challenges increase with complexity | Case-relevant rationale: multilobulation + branch proximity may reduce predictability of complete dome protection. |

| [13] | Microsurgical durability principle/series | Ruptured aneurysms needing anatomy-driven reconstruction | Microsurgical clipping | Durable exclusion with direct visualization of neck/branches/perforators | Justifies clipping when endovascular durability is less predictable; emphasizes branch/perforator protection. |

| [14] | ICA–PCom operative corridor literature | ICA–PCom aneurysms (incl. posterior projection/branch-adjacent) | Pterional exposure; carotid/optic windows (as applicable) | Defines safe exposure/dissection logic | Anchors your technical decision-making to established corridors without broad review. |

| [15] | Complication risk cohorts | aSAH | Standard prevention/monitoring | Rebleeding, vasospasm/DCI, hydrocephalus, CN palsy remain key risks | Frames urgency and why “low-grade” does not mean “low risk.” |

| [16] | Anatomic risk context | Lesions near AChA/perforators; perforator-rich environments | Endovascular vs. microsurgery | Higher procedural hazard with critical perforators/branching | Supports anatomy-based strategy selection and intraoperative protection priorities. |

| [17] | Systems/access literature | aSAH across resource settings | Transfer/imaging/ICU pathways | Delays + infrastructure variability worsen outcomes | Supports one concise systems paragraph: time-to-imaging/time-to-securing matters. |

| [18] | Real-world implementation context | SAH pathways under practical constraints | Flexible protocols | Outcomes depend on matching lesion complexity to expertise/resources | Allows brief acknowledgment of workflow variability without drifting into pharmacology/biomarkers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oprea, S.; Pantu, C.; Breazu, A.; Munteanu, O.; Dumitru, A.V.; Radoi, M.P.; Costea, D.; Baloiu, A.I. A Ruptured Tri-Lobulated ICA–PCom Aneurysm Presenting with Preserved Neurological Function: Case Report and Clinical–Anatomical Analysis. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010073

Oprea S, Pantu C, Breazu A, Munteanu O, Dumitru AV, Radoi MP, Costea D, Baloiu AI. A Ruptured Tri-Lobulated ICA–PCom Aneurysm Presenting with Preserved Neurological Function: Case Report and Clinical–Anatomical Analysis. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleOprea, Stefan, Cosmin Pantu, Alexandru Breazu, Octavian Munteanu, Adrian Vasile Dumitru, Mugurel Petrinel Radoi, Daniel Costea, and Andra Ioana Baloiu. 2026. "A Ruptured Tri-Lobulated ICA–PCom Aneurysm Presenting with Preserved Neurological Function: Case Report and Clinical–Anatomical Analysis" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010073

APA StyleOprea, S., Pantu, C., Breazu, A., Munteanu, O., Dumitru, A. V., Radoi, M. P., Costea, D., & Baloiu, A. I. (2026). A Ruptured Tri-Lobulated ICA–PCom Aneurysm Presenting with Preserved Neurological Function: Case Report and Clinical–Anatomical Analysis. Diagnostics, 16(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010073